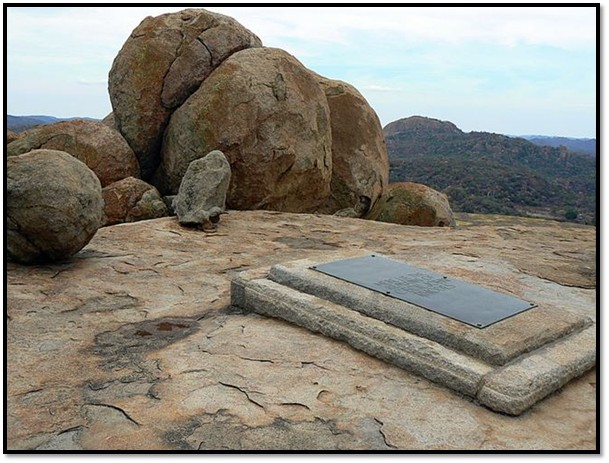

World’s View Matobo, Rhodes’ grave and the Shangani Memorial

Cecil Rhodes, Dr Leander Starr Jameson, Charles P.J. Coghlan, Allan Wilson and the remains of the members of the Shangani Patrol killed in the First Matabele War, are buried here on the summit of Malindidzimu, the “hill of benevolent spirits.” A short walk from the car park takes the visitor to Rhodes’ grave site on the solid granite hill which is surrounded by a natural amphitheatre of massive boulders.

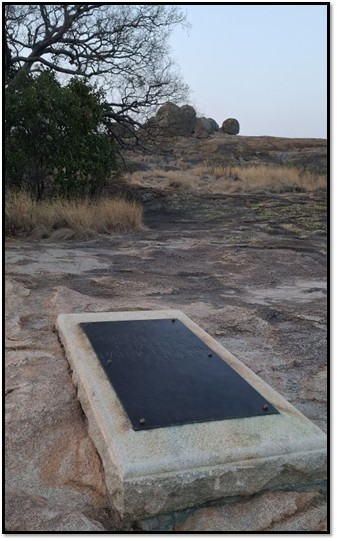

Rhodes’ epitaph reads ‘Here lie the remains of Cecil John Rhodes’

Rhodes’ grave site at sunset

Shortly after the third and final Indaba in September 1896 Rhodes and Dr Hans Sauer went horse riding into the Matobo hills and in Sauer’s words, “we continued on our way by the curling and twisting narrow valleys between the immense boulders scattered about on their summits and sides. Rhodes’ attention was suddenly attracted to a formidable granite dome with some large boulders placed in circular form on the top. He proposed that we should dismount and climb to the top to get a good view. We tied our horses to a tree and after a long, but gradual ascent reached the summit. On arrival there we were rewarded with a magnificent view over the rugged masses of the Matopos. Rhodes was profoundly moved by the impressive panorama before us and said: This is the World’s View.”

A few days later they went again and Rhodes spent an hour on the summit absorbed in his own thoughts. Sauer says, “I have no doubt whatever that it was on this occasion that he made up his mind to be buried on the granite dome that he had named “The World’s View.”

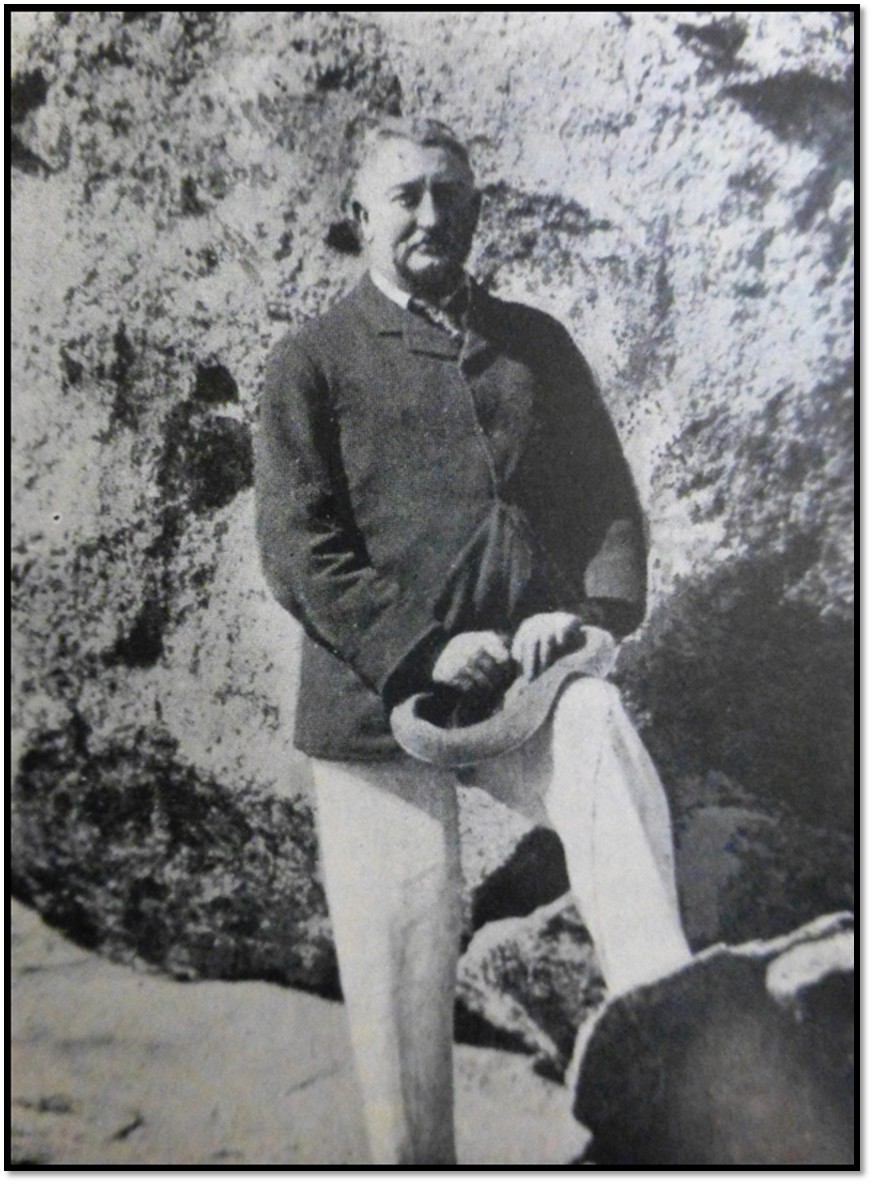

NAZ: Cecil Rhodes in 1899 standing at the spot where his body now lies buried

Sir James McDonald, like Sauer a close friend of Rhodes and general manager of Gold Fields Rhodesian Development Company tells a somewhat different story in his book Rhodes: A life. Earl Grey was administrator of the country from April 1896 to December 1898 and in August 1896 had visited Rhodes on his farm to discuss various matters. Rhodes and Grey went riding in the Matobo Hills before breakfast and about 10am when they returned, Rhodes was in great spirits saying: “Grey and I have made a wonderful discovery; we’ve found a hill from the top of which a marvellous view is to be seen and the ascent is so easy that an old lady of eighty could easily walk up without assistance. You must all ride there this evening and we’ll show it to you.”

About 3pm they all set off and after about an hour’s riding they came to the foot of the hill and after throwing their horses’ reins over their necks were led up by Rhodes to the top of the hill where there was a fine view. Rhodes walked back and forth before saying, “I shall be buried here, looking in that direction (pointing north) and the remains of Allan Wilson and his party must be brought up here also and put inside the memorial I shall put up to their memory. Now don't forget that, the remains of Allan Wilson and his men are to be put there”

McDonald wrote, “We sat for some time afterwards in the shade of the vast round boulders that seemed to have been thrown up from the bowels of the earth and Rhodes was very silent for a time.” Then he said to himself, “Really the peacefulness of it all, the chaotic grandeur of it, it creates a feeling of awe and brings home to one how very small we all are.” Then back he came to the present, “Grey, I call this one of the world’s views.” We all agreed to that, hence its name today: “The World’s View.”

McDonald says they did not visit the site again for two years and all traces of the path became overgrown with bush. They knew the general direction, but there were hundreds of similar hills and two days of searching revealed no result. On the third day Rhodes was so irritable that McDonald avoided talking to him. Five of them were searching on horseback and every morning and afternoon they spent three hours on each occasion searching for the hill.

On the fourth day McDonald says he set out alone to follow up a thought that had occurred to him. They had crossed over a small sandy stream bed running out of a narrow opening in the hills. Two years previous there had been no river here and he remembered a farmer saying that in December 1896 there had been a terrific storm when 23 centimetres of rain fell in four hours. He followed the stream bed and came into a long valley which he recognised from two years previously and soon arrived at the hill and walked to the top.

He arrived back about 11am to find Rhodes and the others at breakfast – they were a gloomy party. Rhodes somewhat sourly said, “Of course you’ve not found it?” In the most cheerful fashion I said, “I have.” He was on his feet in a second, “Are you sure? My horse, Tony – get my horse, Tony. You must take me back there right away McDonald. You’re sure you have got it? Let us be off” and off we went. There was no breakfast for me that day, just a coffee hastily swallowed. The rest of the party were told they would be taken later.

Rhodes pushed McDonald to ride hard and seemed very dubious until we reached the valley which he also remembered. After that he knew they were on the right track and calmed down. Then, “I had to find my hill McDonald, I had to find it; it has stayed with me since I saw it last, I fear I’ve been very irritable the past few days, but I had to find it and I shan’t forget how you stuck to it.”

We were soon on the top of the hill and Rhodes sat down under the shade of one of the rocks, saying to me soon after, “I shall stay here for a time, I am happy here, I want to think for a bit. You go back and have a meal and get a fresh horse and bring Metcalf and the others along. We must chaff them as to their insufficient exploring.” According to James McDonald that was how “The World’s View” was re-discovered.

I am unable to say which version; Sauer’s or McDonald’s is correct. Both were in the Matobo with Rhodes at the time of First Umvukela / Rhodes Indaba. Sir James McDonald’s book Rhodes: A Life was published in 1927; he was drowned when the S.S. Ceramic was torpedoed by U-515 in mid-Atlantic on 7 December 1942. There was only one survivor of the 655 passengers and crew who was taken prisoner aboard the submarine. There is a memorial to Sir James MacDonald in the Matobo National Park. Dr Hans Sauer published his book Ex Africa in 1937 and died in 1939.

Rhodes had made many wills in his lifetime, but in the last he wrote, “I admire the grandeur and loneliness of the Matopos in Rhodesia and therefore I desire to be buried in the Matopos on the hill which I used to visit and which I called ‘A view of the World’ in a square to be cut on the rock on the top of the hill, covered with a plain brass plate with the words thereon, “Here lie the remains of Cecil John Rhodes.”

The funeral of Cecil John Rhodes in the Matobo, Zimbabwe

Although Rhodes remained a leading figure in the politics of southern Africa, he was dogged by ill-health throughout his relatively short life. He was sent to Natal aged 16 because it was believed the climate might help the problems with his heart. On returning to England in 1872 his health again deteriorated with heart and lung problems, to the extent that his doctor, Sir Morell Mackenzie, believed he would only survive six months. He returned to Kimberley where his health improved. From age 40 his heart condition returned with increasing severity until his death from heart failure on 22nd March 1902, aged 49, at his seaside cottage in Muizenberg.

Rhodes had bought the cottage in 1899 from the widow of the late James Robertson Reid. It had been originally built as a thatched roof cottage but had been changed to corrugated-iron prior to Rhodes’ purchase, but in 1904 after his death the roof was replaced with thatch. In April 1921, the cottage was partially destroyed by a huge mountain fire and but for the presence of the fire brigade who were on their way to another call, it would have been razed to the ground. De Beers Consolidated Mines revamped and redecorated the cottage in 1988 to mark the centenary of the company and today it is a Museum staffed by the Muizenberg Historical Society. See the article The death of Cecil John Rhodes at his Muizenberg cottage in 1902 under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

A rare coloured postcard of Rhodes’ cottage at Muizenberg where he died on 26 March 1902

The cottage was left in the care of his personal servant Tony Delacrax until 1904. Thereafter, the roof was altered and the cottage was boarded up until 1932 after which it was handed over to the Northern Rhodesian Government (now Zambia) as a rest and recreational home for their civil servants. In 1937, it was handed over to the Cape Town City Council and in 1953 was converted into a Museum.

After his death, Rhodes' body was taken by night to Groote Schuur where it lay in state. Arrangements were hastily made to carry out his wishes as expressed in his last Will and Testament: “I admire the grandeur and loneliness of the Matopos in Rhodesia and therefore I desire to be buried in the Matopos on the hill which I used to visit and which I called a 'View of the World", in a square to be cut in the rock on the top of the hill, covered with a plain brass plate with the words thereon: "Here lie the remains of Cecil John Rhodes.”

Rhodes' coffin was massive, consisting of three separate coffins - an outer shell of Matabele teak which enclosed two inner coffins, each made of metal. Attached to the sides of the outer coffin were eight huge handles of beaten brass bearing Rhodes' monogram. These were cast, beaten, finished and delivered within four days of the order being given, a team of artisans having worked night and day to do the job.

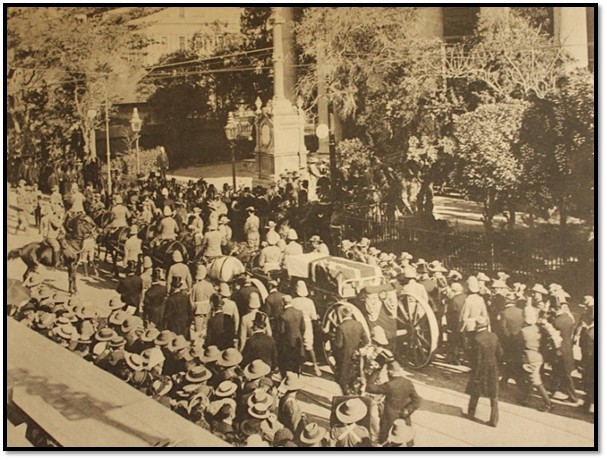

Rhodes’ funeral procession arriving at St George’s Cathedral Cape Town

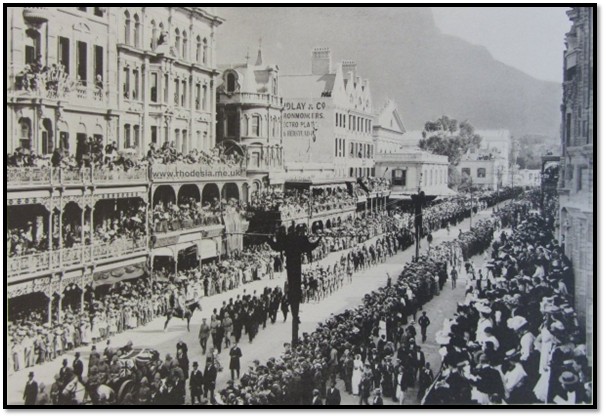

Rhodes’ funeral procession, Adderley Street, Cape Town

After the funeral service, Rhodes' coffin was put on a special train at Cape Town station - its funeral carriage draped with black velvet and purple silk and the train travelled northwards for five days across the entire length of South Africa and then to Bulawayo. At every significant station along the way, thousands of mourners lined the flower-laden platforms.

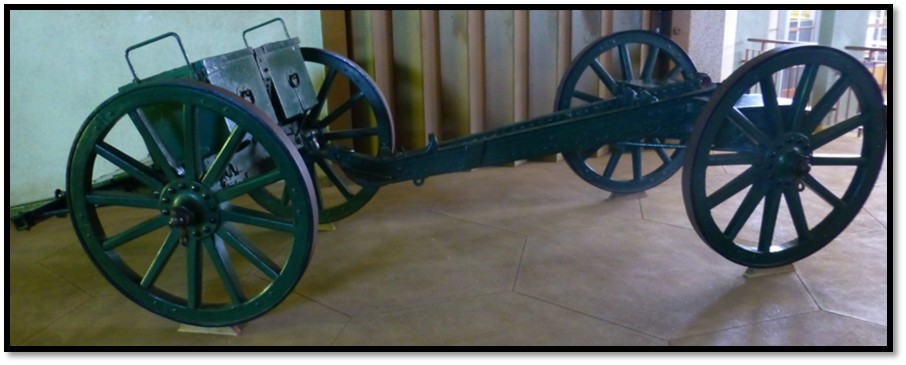

The gun carriage that bore Rhodes’ coffin – now at the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe at Bulawayo

The gun-carriage itself is described by Roger Summers in an article called Some Stories behind historical relics in the National Museum, Bulawayo in Rhodesiana Publication No 26 of July 1972. It is the carriage of a mountain gun, probably a RML seven-pounder Rifled Muzzle Loader (RML) used initially by the Indian Army and later at the battle of Chua Hills at Fort Massi-Kessi [see the article on How Manicaland was annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Unfortunately after many years of neglect the gun-carriage fell to bits from dry-rot and had to be restored by Mr Perks, a wagon builder, who was forced to substitute wagon wheels which are a bit smaller than the original wheels. The restoration was paid for by Stanley and John Sly of Haddon and Sly and was then presented to Bulawayo Municipality. It stood outside the Town Hall before being moved to Government House and finally to the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe at Bulawayo.

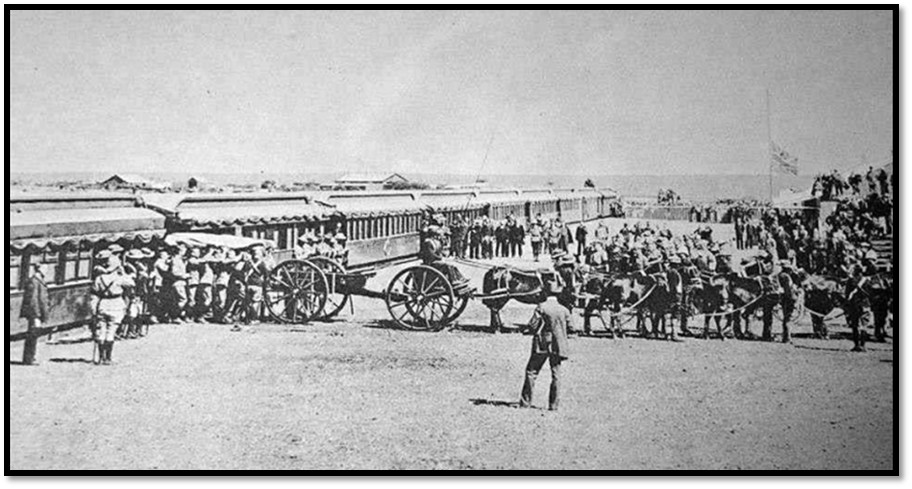

For the procession from Bulawayo station to the Drill Hall the gun-carriage was hauled by a team of eight mules each led by a groom.

Rhodes’ coffin being loaded onto the gun carriage at Bulawayo on Tuesday 8 April 1902

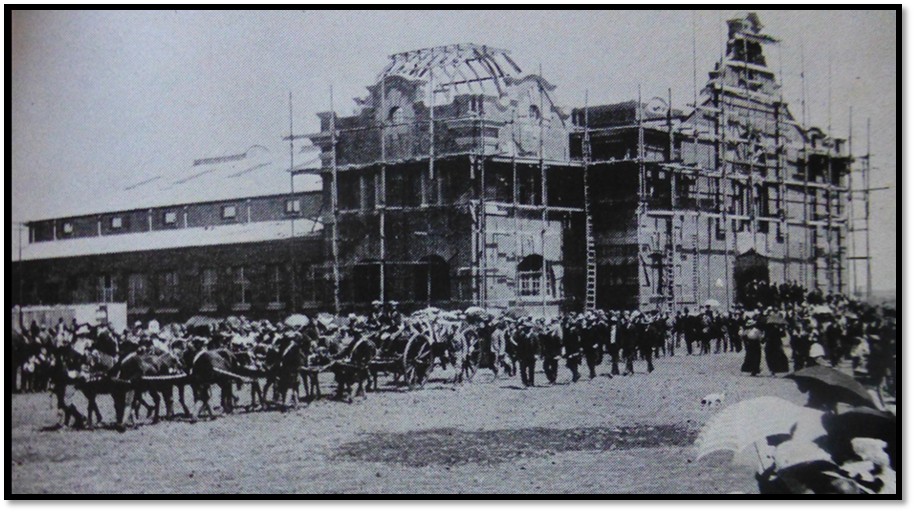

Rhodes’ funeral cortege leaving Bulawayo drill Hall for burial in the Matobo Hills

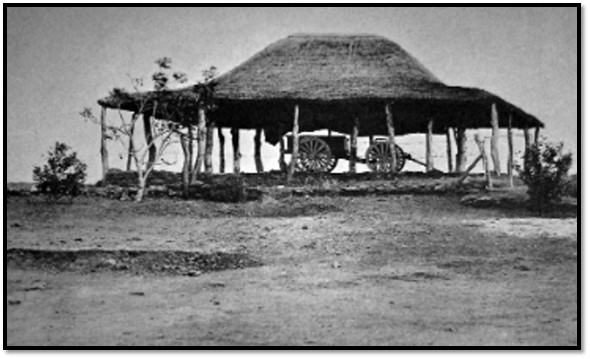

On 9 April 1902 after lying in state at Bulawayo, followed by another funeral service, the funeral cortege left Bulawayo Drill Hall with the coffin resting on a gun-carriage pulled by mules to Rhodes’ farm, Westacre Estate, on the edge of the Matobo Hills where the gun carriage spent the night under his Summer House as seen in the photo below. See the article Rhodes Summer-house under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Rhodes’ coffin on the gun carriage at the Summer House

From Westacre Estate the gun carriage and coffin were drawn by oxen who pulled it to the summit of Malindidzimu without the assistance of the British South Africa Police on drag-ropes. A special funeral road of more than 25 kilometres having been carved through the rocky terrain during the preceding days by a team of about a thousand amaNdebele. Some of these historic photos are from Cecil John Rhodes: A Chronicle of the funeral ceremonies from Muizenberg to the Matoppos March – April 1902

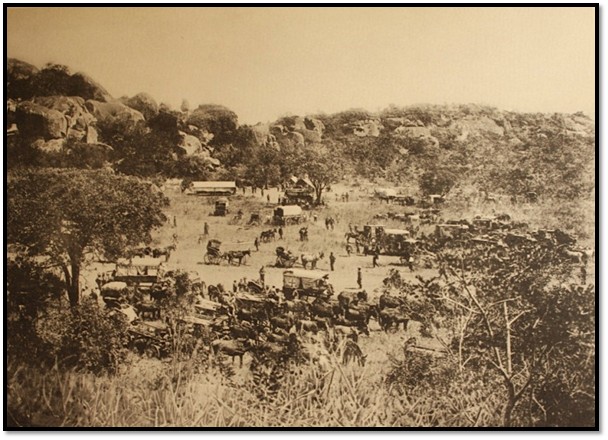

There were no motor cars in Bulawayo then, but every imaginable conveyance of those times was brought into use for the occasion – Zeederberg’s coaches which used to convey mails and passengers throughout Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and to and from the south, joined by buckboards, Cape carts, all drawn by spans of mules, utility carts, ox-wagons and bicycles and a big contingent on horseback. Until three weeks previously the road was merely a rough cattle track and despite the work put into it was difficult to negotiate at times, particularly on entering the hills where gangs of work men were placed at various points to make very necessary repairs after the passage of heavy vehicles.

Some of those camping in the Matobo Hills overnight for the funeral next day

At the main outspan the mules drawing the gun carriage were replaced by twelve black oxen, which had been specially trained during the preceding fortnight to mount the steep approaches with a heavy load and to the relief of those in charge the oxen at these points took the strain, as was said at the time “as quietly as if they were ploughing a furrow” and the gun carriage arrived safely at the summit. Troopers of the British South Africa Police had been stationed at the difficult sections of the route holding guide ropes attached to the gun carriage in case the oxen failed to negotiate the slippery slopes.

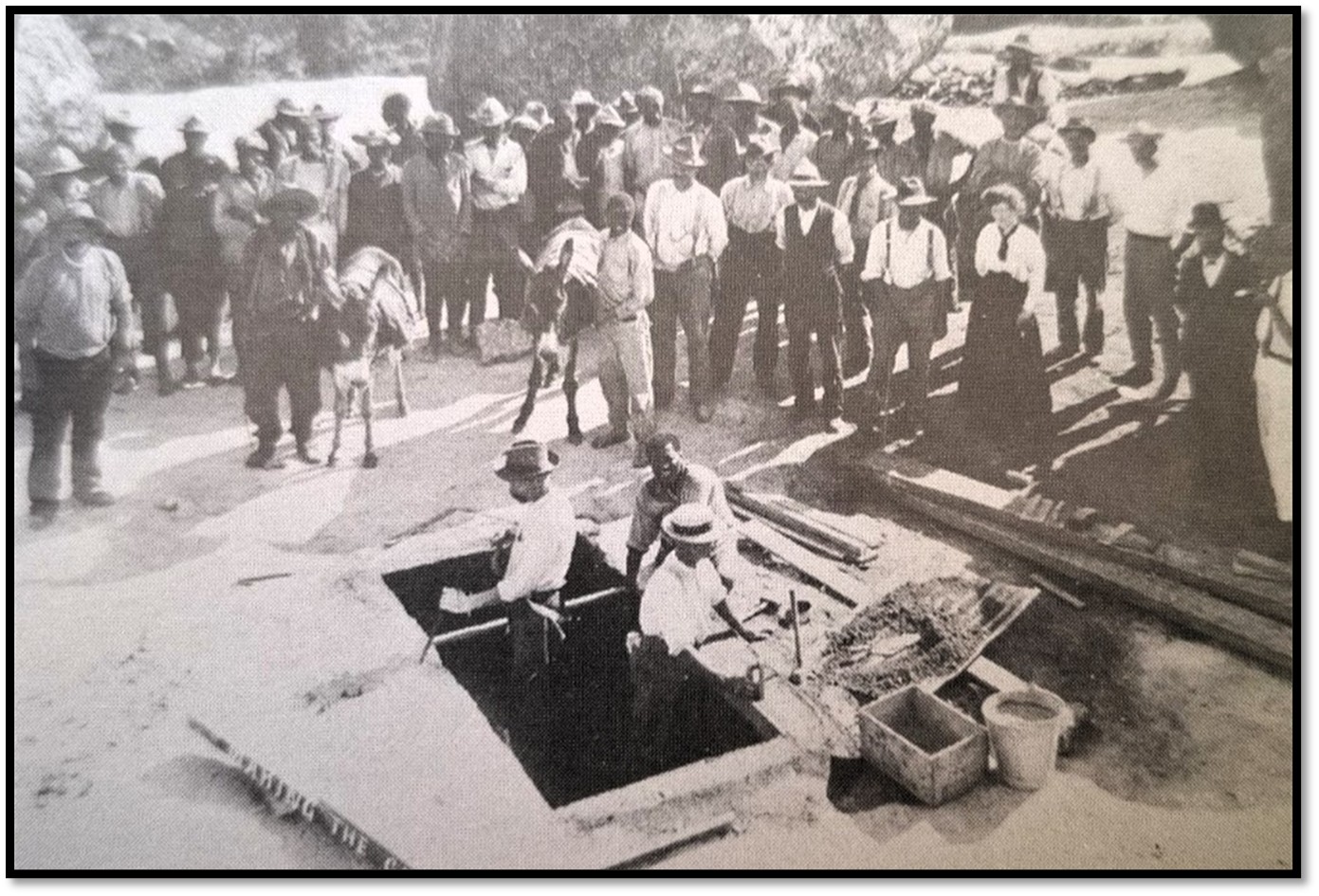

NAZ: Final preparations to Rhodes grave being made

A pyramidal hoist lowers Rhodes’ coffin deep into the rock of Malindidzimu

On the 10 April 1902 Rhodes' coffin was finally embedded at the summit of 'World's View', a huge dome of granite which the local Kalanga people refer to as Malindidzimu ('the haunt of the ancestral spirits')

The amaNdebele Chiefs requested that guns were not fired at the funeral as tradition dictates because it would disturb the spirits in the vicinity; they sent him on his way with the royal salute "Bayete." It was at the burial ceremony that Bishop Gaul of Mashonaland read the verse by Rudyard Kipling which subsequently became so well known:

“That immense and brooding spirit still

Shall quicken and control

Living he was the land, and dead

His soul shall be her soul.”

The Shangani Memorial

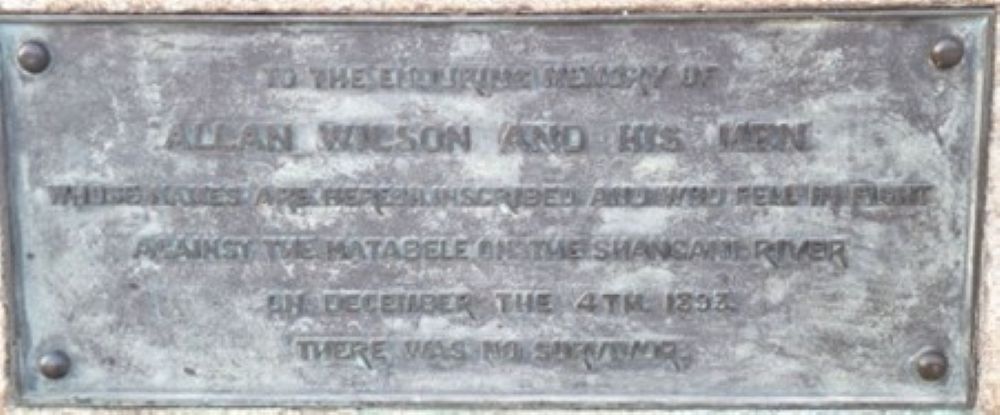

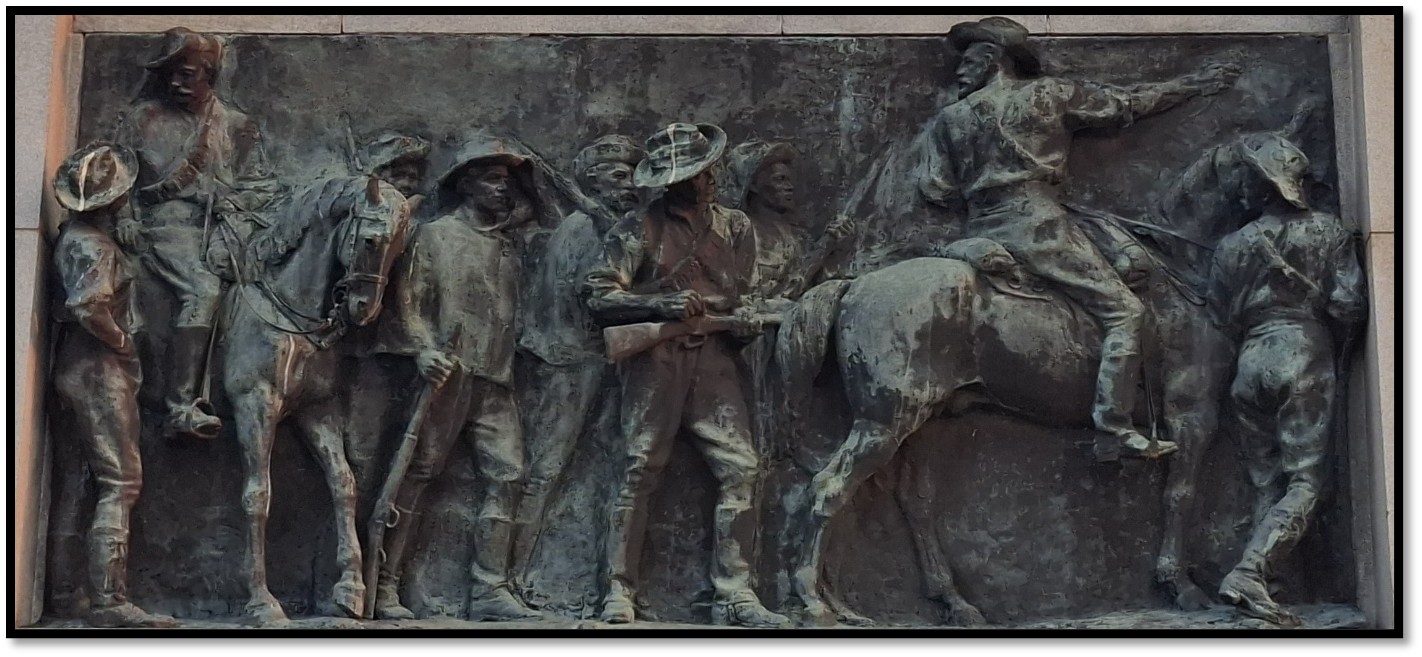

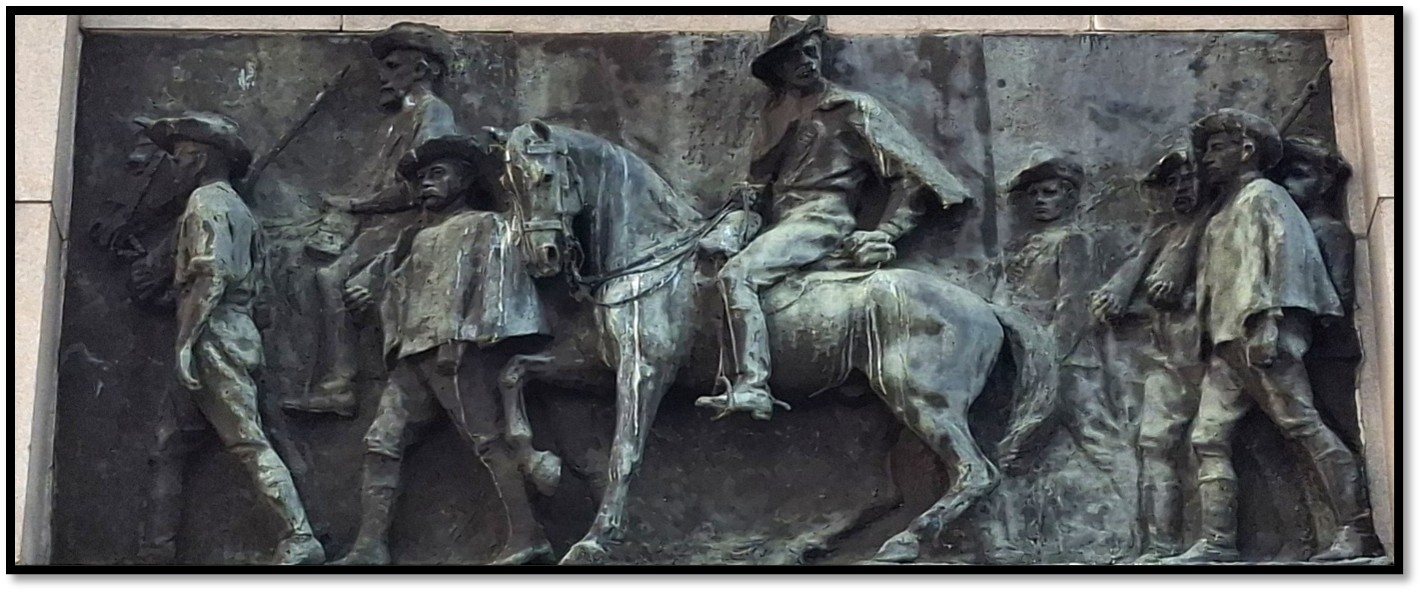

In March 1904, the remains of the small party of Victoria Rangers and Salisbury Horse led by Allan Wilson were buried some one hundred and fifty yards away in an imposing granite monument designed by Sir Herbert Baker[1] with four bronze panels by the sculptor John Tweed. The main inscription reads: “To the enduring memory of Allan Wilson and his men whose names are hereby inscribed and who fell in fight against the Matabele on the Shangani River, December 4th, 1893. There was no survivor.”

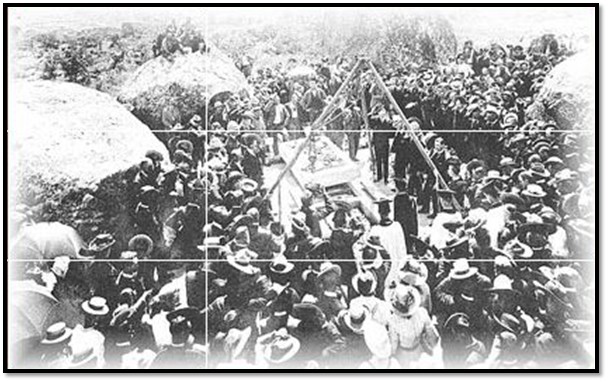

NAZ: The opening ceremony of the Shangani Memorial

Inscription on the Shangani Memorial

The battle took place on 3rd December 1893 far to the north on the Shangani River at Pupu[2] in Matabeleland North, north-east of Lupane[3] and Major Allan Wilson and all of his patrol of 33 men were killed. In February James Dawson and James ‘Paddy’ Reilly recovered their remains. (Dawson’s inscription on the tree: “To Brave Men” can be seen at the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo) and their remains were buried at Great Zimbabwe, until re-buried in the Matobo at World’s View.[4]

The Shangani Memorial at Malindidzimu ('the haunt of the ancestral spirits') Matobo

For additional information on the battle see the article Three oral history statements made in 1937 by amaNdebele warriors present at the killing of Allan Wilson and thirty-three other Europeans on 4 December 1893 at the Shangani River under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

West Panel: Capt Borrow (mtd) Sgt Brown, Sgt Money, Sgt-Major Harding, Major Wilson (mtd) Capt Kirton (mtd) Cpl Colquhoun, Cpl Kinloch

North Panel: Tpr Dewis, Lieut Hughes (mtd) Tpr Brock, Tpr Dillon, Tpr Demos, Tpr Watson, Tpr Britton, Capt Grrenfield, (mtd) Sgt Birkley

East Panel: Tpr Nunn, Tpr Tuck, Tpr Oliver, Capt Fitzgerald (mtd) Tpr Robertson (mtd) Tpr Thompson, Tpr Bath, Tpr Hay-Robertson, Sgt Bradburn

South Panel: Tpr Meikle, Lieut Hofmeyer (mtd) Tpr Mackenzie, Capt Judd (mtd) Tpr Welby, Tpr Abbot, Tpr Vogel, Tpr Mellet

Shangani Patrol Members commemorated on each Memorial Panel

There are some spelling differences between the names on the plaque above and those listed in the Dawson article that came from Robert Cary’s book A Time to Die.

Although the battle took place on 4 December 1893, the remains of the dead were only collected by Dawson and Reilly in February 1894. By late December it was clear to those in Bulawayo there were no survivors and Captain Woon and a small force were sent off to establish the facts but were defeated by the heavy rains. Then in early February 1894 a party of four set off under James Dawson and James ‘Paddy’ Reilly.

After a long and wet journey north they crossed the Shangani river and met up with some parties of dispirited amaNdebele regiments where Dawson persuaded an inDuna to take them to the battle site at Pupu. Dawson writes, “After walking about three miles along a path, he halted and pointed ahead. We dismounted and walked about seventy yards (64 metres) when we came to an open space in the bush which was very thick all round, and then we saw a number of bones scattered about. After looking solemnly on with bared heads for a while, we set to work and collected what remained of that brave band and piled them in a heap while our people were digging a trench. It must be remembered that these remains had been lying there for a long time during a very wet season and were quite bleached. We got every visible scrap together, including the skulls of all and buried them under a large Mopane tree on which I cut with knife and hatchet a cross with the legend “To brave men.” The only articles of consequence which we picked up were a watch and a ring, both of which were recognised by those interested and handed over.”

In his diary Dawson wrote the battle site was a small space of about 15 yards (14 metres) in diameter, literally covered with bones, men, and horses more or less mingled…all the heads were in this small space except one which was about 10 yards (9 metres) off. This was the man who was so hard to kill that they were almost going to leave him alone because the amaNdebele thought he was a wizard. This we determined to bring back for recognition – a strong built dark man with clipped beard and moustache.

James Dawson said there was no doubt that Wilson's men had stood together and made their last stand in that small area. “The fight started a little way off where Lobengula’s wagons had been stopped and our men, finding they were far outnumbered and likely to be worsted, retreated in the hope of being able to rejoin the main body. But unfortunately, a great number of the Matabele had crossed the river in the early hours of the morning and Wilson's party met them. Wilson had just time to send three men[5] to tell Forbes where they were, and explain their plight, when they were surrounded and hemmed in. The native say they could not understand why all should have stayed, as some of them could have escaped had they tried. But they had not tried because some of the horses had been killed, and those who had horses resolved not to desert their comrades in distress. So, they stood there and fought the thing out.

The natives were very loud in their praise of the way in which they fought. They called them ‘men of men’ - the very best of men they could wish to have before them. It was only the Maxims, they thought, which fought them before; but they said they now saw what a few men could do with their rifles and revolvers. I consider this fight did more to settle the whole Matabele difficulty than a good many other things that have occurred, for from that day to this, the Matabele have been thoroughly subdued.”

Dawson said it was difficult to arrive at the number of amaNdebele who were killed in the fight. He explained, “They took away all their dead with the exception of about half a dozen we saw lying there. The natives say these were men without any friends or they would have been taken away and buried. But you could tell by the trees how terrific must have been the fire, for the branches and stems of the trees were all torn to shreds by the bullets. It was one continual forest, and they fired out of the trees on all sides. Wilson’s party were in a small, lightly wooded spot in the forest, which was so dense they could not see far in any direction. One old man whom I brought in - he was the head of a little town - said that he went off with a party of men to take part in the fight, when he heard a shout and before they did anything at all, six of his men were lying dead and he then went back. This sort of thing would have gone on from early morning until well in the afternoon.”

For a much fuller account of the battle itself and the men in Allan Wilson’s patrol who took part see the article James Dawson’s account of finding the remains of Allan Wilson and his patrol under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The remains were exhumed from Pupu and buried at Great Zimbabwe as most of them had been Fort Victoria (present-day Masvingo) volunteers. The photo below is from a +/- 1903 lantern slide kindly provided by Tim Ewbank.

John Tweed, the sculptor, was commissioned to design the brass memorial plaques for the Shangani Memorial to be sited in the Matobo, despite much opposition from the citizens of Fort Victoria. “Secret plans were made, and one morning in February 1904 the townspeople woke to find that the bodies had been disinterred during the night and were already on their journey to the Matobo. Fort Victoria was furious. A mass meeting was held and resolutions were passed castigating the government's action as ‘high handed’ and ‘illegal;’ the Volunteers in the town unanimously handed in their resignations in protest against the ‘insult’ which had been done to them.”

Their bones were buried at the present-day Shangani Memorial. The Bulawayo Chronicle of 9 July 1904 has a long description of the opening ceremony summarised as follows: “Soon after 11 o’clock [on the 5 July 1904] the Pioneers formed up and led by the Southern Rhodesian Volunteers (SRV) the band playing funeral marches, marched to the summit of the View of the World, where a square was formed of the SRV with the Pioneers inside. A short delay occurred, but soon His Honour the Administrator, accompanied by the Archbishop of Capetown, Archdeacon Reeves and Colonel F. Rhodes advanced to the Memorial, where the service was conducted. This consisted of Hymns 165 and 540, with short prayers. The unveiling of the Memorial was announced by a flourish of trumpets, after which and at the conclusion of the dedication, an address was given by His Honour the Administrator.”

The Shangani Memorial itself

The Bulawayo Chronicle article provides some details on the construction of the Memorial that is situated 102 metres (112 yards) south east from Rhodes’ grave. It is composed of massive blocks weighing from three to seven tons that were quarried from an adjacent kopje. The square structure has sides measuring 7 metres (23 feet) and is 10 metres (33 feet) high. Internally is a cubic vault of 3 metres (10 feet) where the remains of Wilson and his colleagues are placed. Mr J. Loughton oversaw construction.

The Shangani Memorial, Matobo

Rob Burrett writes that Sir Herbert Baker was not happy that the Shangani memorial was moved away and downhill so as not to dominate Rhodes’ own grave.[6]

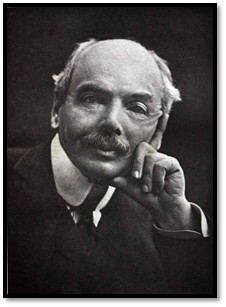

Sir (Dr) Leander Starr Jameson ‘Dr Jim‘ 1st Baronet, KCMG, CB, PC (1853 – 1917)

Best known for his leading role in the Jameson Raid his achievements in life included much more. Jameson was born on 9 February 1853 in Edinburgh, Scotland, the youngest of eleven children. His father was a hard-up Scottish lawyer and journalist who died in 1868. An elder brother financed his university education and he qualified as a medical doctor in 1877 at University College, London. In 1878 he joined a Kimberley medical practice where he earned his ‘Dr. Jim’ nickname.

Physically below average height, stocky and bald, he radiated energy and leadership. In Kimberley he developed a life-long friendship with Cecil John Rhodes and shared a house from 1886.[7] Sent by Rhodes to persuade Lobengula to grant a mining concession to Rhodes’ agents he treated the King’s gout successfully and was made an inDuna of the Imbeza Regiment. In 1888 King Lobengula signed the Rudd Concession granting the British South Africa Company (BSAC) exclusive mining rights in what were considered his territories (Matabeleland & Mashonaland) See the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession? under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com[8]

In 1889 Jameson abandoned his medical practice and joined the 1890 Pioneer Column to Mashonaland.[9] From then on his activities were tied to Rhodes’ plans for the north.[10] In 1891 he succeeded A.R. Colquhoun as Administrator of Mashonaland. [11] In 1893 he was the key co-ordinator in the Matabele War[12] that ultimately ended with the deaths of Allan Wilson and the Shangani Patrol.[13]

Dr Leander Starr Jameson

Rhodes, frustrated by Kruger, President of the South African Republic, in his plans to create a British federation in southern Africa, decided to cause an Uitlander revolt in Johannesburg to overthrow the government. The uprising would coincide with an invasion of the Republic by Jameson. On 29 December 1895, Jameson led about 500 mounted BSA Troopers from Pitsani in present-day Botswana in what became known as the Jameson Raid against the Boers in Johannesburg in support of the foreign workers (Uitlanders) that Rhodes, then the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, hoped would lead to the overthrow of the Transvaal Republic. Although the Raid ended as a defeat Jameson was portrayed in the British press as a daring hero.[14]

Jameson and the raiders were put on trial in London in February 1896 and the BSAC was forced to pay compensation to the Transvaal Republic. Dr Jameson was "found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment as a first-class misdemeanant” for a gaol term of fifteen months but released from Holloway in December due to illness. Rhodes resigned as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony.

The British Colonial Secretary, Chamberlain, had been actively involved in the planning of the Raid and Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister supported him in threats to the BSAC to withdraw the Company’s Charter if any of Chamberlain’s cablegrams were revealed during the trial.

The imprisonment of most of the BSA Police seriously reduced the number of white fighting men in Matabeleland and the amaNdebele seized upon this weakness and rose in late March 1896 in the Matabele rebellion or Umvukela killing about 10% of the white men, women and children and their servants.[15]

The Jameson Raid was later quoted by Churchill as a major reason for the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 to 1902. In October 1899 Jameson was caught in the Boer siege of Ladysmith between November 1899 and February 1900, becoming seriously ill with dysentery. His health had already been harmed by repeated bouts of malaria in Rhodesia. Rhodes died on 26 March 1902 and a grieving Jameson was determined to repair the political damage done between Boer and British by the Raid and to complete Rhodes’ vision of a unified South Africa.

Jameson’s career after his role as Administrator of Mashonaland

Despite the ignominy of the Raid Jameson had a successful career. In 1903 he became the leader of the Progressive Party in the Cape Colony and served as Prime Minister from 1904 to 1908. In 1907 for his role in the unification process Jameson was made a Privy Councillor. He was leader of the Unionist Party (South Africa) from 1910 – 12 when he returned to England.

Sir Leander Starr Jameson died on 26 November 1917 at his home, 2 Great Cumberland Place, London. His body was laid in a vault at Kensal Green Cemetery until 1920 when he was buried on

Malindidzimu, close to his great idol, Cecil John Rhodes. His grave states, “Here lies Leander Starr Jameson.”

Tributes to Dr Jim

In Rudyard Kiplong's autobiography he writes that "If—" was "drawn from Jameson's character."

Elizabeth Longford wrote of him, "Whatever one felt about him or his projects when he was not there, one could not help falling for the man in his presence.... People attached themselves to Jameson with extraordinary fervour, the more extraordinary because he made no effort to feed it. He affected an attitude of tough cynicism towards life, literature and any articulate form of idealism, particularly towards the hero-worship which he himself excited…”

Seymour Fort wrote of L.S. Jameson, “It was not his wont to talk at length, nor was he, unless exceptionally interested, a good listener. He was so logical and so quick to grasp a situation, that he would often cut short exposition by some forcible remark or personal raillery that would all too often quite disconcert the speaker.

Despite his adventurous career, mere reminiscences obviously bored him; he was always for movement, for some betterment of present or future conditions, and in discussion he was a master of the art of persuasion, unconsciously creating in those around him a latent desire to follow, if he would lead. The source of such persuasive influence eludes analysis, and, like the mystery of leadership, is probably more psychic than mental. In this latter respect, Jameson was splendidly equipped; he had greater power of concentration, of logical reasoning, and of rapid diagnosis, while on his lighter side he was brilliant in repartee and in the exercise of a badinage that was both cynical and personal...

... He wrapped himself in cynicism as with a cloak, not only to protect himself against his own quick human sympathy, but to conceal the austere standard of duty and honour that he always set to himself. He was ever trying to hide from his friends his real attitude towards life, and the high estimate he placed upon accepted ethical values... He was essentially a patriot who sought for himself neither wealth, nor power, nor fame, nor leisure, nor even an easy anchorage for reflection. The wide sphere of his work and achievements, and the accepted dominion of his personality and his influence were both based upon his adherence to the principle of always subordinating personal considerations to the work in hand, upon the loyalty of his service to big ideals. His whole life seems to illustrate the truth of the saying that in self-regard and self-centredness there is no profit, and that only in sacrificing himself for impersonal aims can a man save his soul and benefit his fellow men.

Sir Leander Starr Jameson’s grave at Malindidzimu

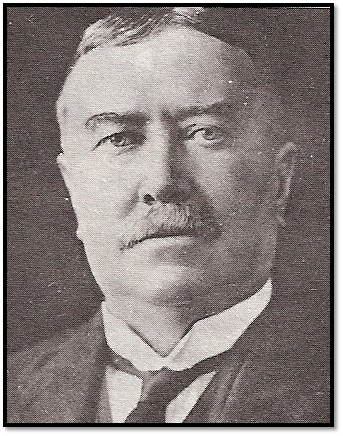

Sir Charles Patrick John Coghlan KCMG (24 June 1863 – 28 August 1927)

Coghlan had ambitions to be a Barrister, but his father’s death from dysentery and shortage of funds forced him to leave university in 1882 and join his eldest brother James in Kimberley in a law firm. In 1886 he was admitted to practise as an advocate in the courts of West Griqualand and in 1887 he and his elder brother formed the firm of Coghlan and Coghlan. Kimberley was at the centre of the diamond trade and the brothers gained a reputation for their knowledge of the mining industry.

Elected to the Kimberley town council in 1897, he married Gertrude Mary Schermbrucker on 10 January 1899.

Sir Charles John Patrick Coghlan

They moved to Bulawayo in 1900 finding the town to be very basic and many of the buildings rundown. The following year their first child was born, but the baby lived only three days. A second child, a girl named Petal, was born the following year 1902. Coghlan was admitted to the Rhodesian bar and formed a legal practice, Frames and Coghlan. In 1902 he formed Coghlan and Welsh and in 1907 expanded into Salisbury as Coghlan, Welsh and Tancred.

Coghlan was elected in 1908 to the Southern Rhodesian Legislative Council and at a banquet for Lord Selborne, the departing High Commissioner, Coghlan spoke of the BSAC and Southern Rhodesia working towards entering the Union of South Africa whilst rejecting the notion of responsible government, meaning self-government while retaining colonial status. However at a later date he found that the speeches of Louis Botha, the Prime Minister and Hertzog, the Attorney-Gene to be unfair to South Africans of British origin. At the time he supported rule by the BSAC and opposed any amalgamation of Southern Rhodesia with Northern Rhodesia.

During World War I, Rhodesia's white population had been split between the Unionists, who wanted union with South Africa, and the Responsible Government Association (RGA) who wanted self-rule, although Herbert Longden, the RGA’s leader, believed Southern Rhodesia still lacked the population and resources for self-rule. The BSAC backed the Unionists, believing the Chartered company would get a better price for its assets from South Africa than from Southern Rhodesia. Business interests were also pro union, since they hoped South Africa would be able to provide cheap labour and it was they who controlled the local press.

The 1922 referendum results were 8,774 for responsible government and 5,989 for joining South Africa. Having led the responsible government movement Coghlan was elected as Southern Rhodesia's first Prime Minister when it became a self-governing colony within the British Empire.

Coghlan was buried near Cecil Rhodes' grave, at Malindidzimu in the Matobo Hills near Bulawayo.

Grave of Charles John Patrick Coghlan

References

R. Cary. A Time to Die. Howard Timmins, Cape Town 1969

F.E. Masey. Cecil John Rhodes: A Chronicle of the funeral ceremonies from Muizenberg to the Matoppos March – April 1902. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1972

J.G. McDonald. Rhodes: A Life. Books of Rhodesia 1971

T. Ranger et al. Malindidzimu. Khami Press, Bulawayo 2013

H. Sauer. Ex Africa. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1973

C. Shee. The burial of Cecil Rhodes. Rhodesiana Magazine. No. 18 of July 1968. P37-46

R. Summers. Some Stories behind historical relics in the National Museum, Bulawayo in Rhodesiana Publication No 26 of July 1972

Wikipedia

[1] Sir Herbert Baker (1862 – 1946) was the most prominent architect in South Africa particularly in the period 1892 – 1912 and much favoured by Rhodes. Wikipedia lists many of the schools, churches and government buildings designed by Baker including Rhodes’ Memorial, but not the Shangani patrol Memorial

[2] Pupu marking the site of the battle is National Monument No 13

[3] Lupane on the Gwaai river is south of the Shangani river. Pupu is approximately 45 kilometres north-east of Lupane on the northern side of the Shangani river

[4] For a full description of James Dawson and James (Paddy) Reilly’s search for the Shangani patrol’s remains see the article James Dawson’s account of finding the remains of Allan Wilson and his patrol under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[5] The three men were the scouts Burnham and Bain and Trooper Gooding.

[6] Malindidzimu, P41

[7] Colvin describes their friendship ‘as strong as a marriage bond’ and a ‘marriage of twin minds.’

[8] See the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession? under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[9] See the article The Pioneer Column’s march from Macloutsie to Mashonaland under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[10] Rotberg, was ideally suited to be an imperial adventurer as he was a born buccaneer, decisive and showing contempt for diplomacy and morality

[11] See the article Was Archibald Ross Colquhoun; first Administrator of Mashonaland 1890 – 92, a failure or was he actively undermined by Dr Jameson? under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[12] See the article The build-up to the 1893 Matabele War under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[13] See the article James Dawson’s account of finding the remains of Allan Wilson and his Patrol under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[14] See the article The Jameson Raid under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[15] See the article Bulawayo and the Matabele Rebellion (or Umvukela) – Part 1, the first few weeks and the patrols sent to rescue outlying farmers, prospectors and storekeepers under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com