Khami – capital of the Torwa state

From central Bulawayo take 13th Avenue going west that changes to Anthony Taylor Avenue, then Steel Works Road and after crossing Mpopoma Avenue changes to Khami Road. Cross Khami dam Bridge and follow signposts to Khami Museum (about 22 KM)

Khami is spread over a 180 hectare area along the Khami River, with the site comprised of 14 drystone wall built platforms. An unknown number of platforms were, however, flooded by the damming of Khami River in 1929.

Introduction

Khami and the area have thousands of years of occupation starting with the Early Stone Age (ESA) Their tools are exhibited at the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe at Bulawayo;[1] however although the ESA period can be considered at least 1 million years ago, the period is not securely dated as most of the sites where ESA axes and cleaver tools have been found lack precise chronological context.

Middle Stone Age (MSA) artefacts have been quite commonly found in the form of triangular points and blades and are more securely dated between 300,000 – 2,000 years ago. Late Stone Age (LSA) tools are common in the form of microlithic (small stone tool) blades and scrapers, rock abundant rock art sites, beads made from ostrich eggshells and organic tools. LSA hunter-gatherer populations were eventually replaced with the arrival of Bantu-speaking farming communities during the Iron Age.

By the end of the first millennium AD villages populated by ancestral Kalanga (western Shona) farmers using iron implements and pottery had become established on and around a rocky outcrop known as Leopard's Kopje to the north of the Khami river. Occasional glass beads from excavations there indicate the beginnings of trading contacts with the east coast of Africa.

Clearly throughout the ages the site would have been attractive for its proximity to the Khami river in an area where annual rainfall typically averages 500 – 700 mm. However this area has the added attraction of nearby greenstone gold belts and also prime grasslands that are ideal as cattle pastures.

Oral tradition reveals that Khami was a major Kalanga religious centre. Nobody was allowed to repair or rebuild collapsed walls and even cut trees because such actions disturbed the resting ancestors. Lobengula, the last of the amaNdebele Kings declared Khami a royal reserve to be used for religious ceremonies

Khami is spread over a 180 hectare area along the Khami River, with the site comprised of 14 drystone wall built platforms. An unknown number of platforms were, however, flooded by the damming of Khami River in 1929.

Khami was a crucial trade centre and capital for the Torwa dynasty (c. 1450 - 1650 AD) succeeding Great Zimbabwe with trade links to the East African coast. Dated ceramics and beads from excavations conducted by Keith Robinson between 1947 and 1956 show that these trading contacts with the east coast and the Portuguese continued during the 16th and 17th centuries.

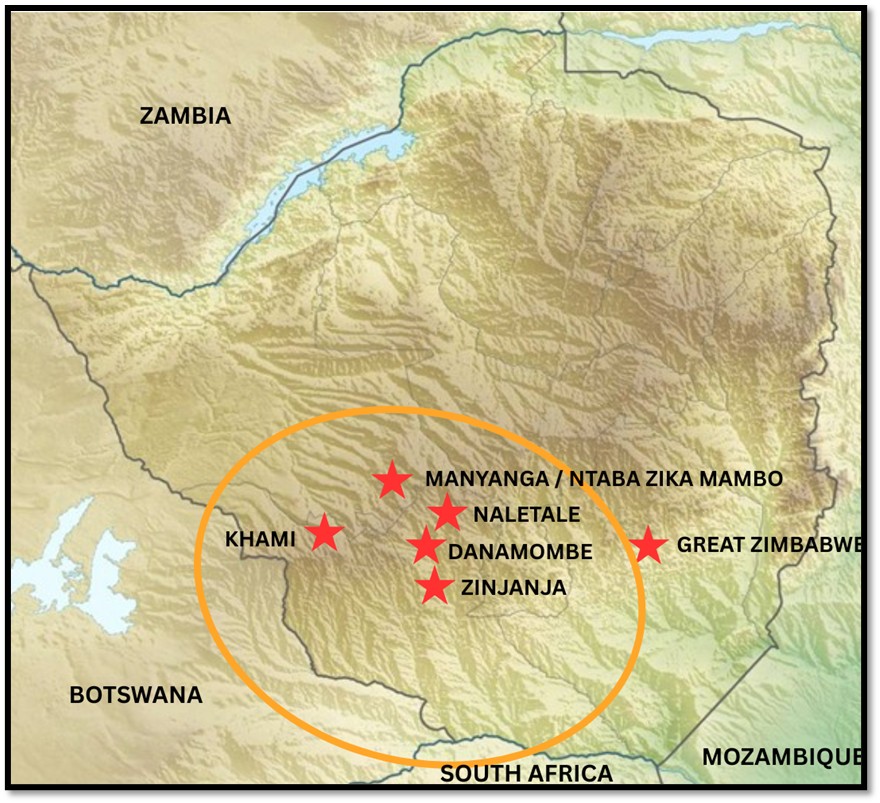

The Portuguese called the Torwa state Butua and it was initially centred at Khami but in the 1600’s the capital moved to Danamombe. The defining characteristic of the Torwa state was its architecture, mostly made up of terraced platforms using dry-stone masonry. The state covered a large area that included present-day southern and south-western parts of Zimbabwe, north-east Botswana, and northern South Africa.

Burrett and Hubbard state that, “Although probably not a single, centralised state with one authoritarian leadership, certainly in its core area the influence of the king and his advisers would have been unquestioned.”[3]

Present-day Zimbabwe map showing location of the larger Torwa settlements. The orange circle shows the approximate extent of the Torwa state

The main economic activities of the Torwa state were mining for gold that was traded with Swahili traders and the Portuguese on the Indian Ocean coast, cattle farming, agriculture and cotton spinning. Metal processing of gold, copper and iron provided a range of utilitarian and ornamental objects. The authors of the paper The chronology, craft production and economy of the Butua capital of Khami, southwestern Zimbabwe write, “Material culture items recovered suggest that, alongside animal husbandry, pottery making, agriculture, metal working and ivory working were important components of its economy.”[4]

The use of elaborate stone walls to demarcate specific areas is a characteristic of the Zimbabwe Culture and suggests a distinct social hierarchy, separating the elite residences from the commoner areas. Most archaeologists agree that the platforms demonstrate the clear spatial division between the ruling elite, who lived in the stone-walled platforms, and the common population who lived in unwalled areas surrounding them. The specific layout of huts and animal enclosures provides insight into the daily life and social structure of the inhabitants.

Khami was recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1986.[5]

Zimbabwe Culture

Within the wider southern African region, archaeologists suggest that Zimbabwe Culture first emerged at Mapela, then Mapungubwe in 1220 – 1300 AD, relocated to Great Zimbabwe (peaked 1200 – 1300 AD, declined 1400’s, abandoned 1500’s) followed by Khami’s emergence around 1400 AD. It is conceivable that around 1250 AD some of the Leopard’s Kopje communities in south-western Zimbabwe developed into Khami, there are pottery similarities. Between 1425 and 1685, Khami was the capital of the Torwa state, which was succeeded by Danamombe, the centre of the Rozvi-Changamire dynasty that ruled from multiple capitals from 1685 to 1839.

Many of the stones in the roofed passage on the main platform were cracked from fire damage and archaeologists speculate this may have happened when Khami was attacked in 1644 by a defeated usurper who obtained help from a Portuguese warlord during a civil war that weakened the Torwa dynasty.

Burrett and Hubbard write that the wealth accumulated by the Torwa state from cattle and the international trade attracted the envy of the Rozwi[6] who invaded at some date before 1683.[7] The Rozvi were led by Changamire Dombo, but it was his son Kambgun Dombo who became the ruler of Butua in what had formerly been the Torwa State. In addition they drove the Portuguese off the northern plateau of present-day Mashonaland See the article The Portuguese Feiras and trading settlements of the 16th – 17th century on the Northern Mashonaland Plateau and Manicaland under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Not all present-day archaeologists agree with the model that the demise of Khami in the 1600’s resulted in the development of yet another capital at Danamombe. In the North lay the Mutapa state which had multiple capitals between the northern Mashonaland plateau and the Lowlands.

An alternative view of Khami’s development

Having discussed the above it is important to note the conclusions drawn in the article The chronology, craft production and economy of the Butua capital of Khami, southwestern Zimbabwe.

The authors excavated in a number of sites around Khami, but outside the platform sites generally associated with the elites at Khami and described in some detail below. Their indicated dates of early 1400’s show that Khami was not a successor state to Great Zimbabwe, but rather they developed independently and were contemporary rather than the successor states as stated by Pikirayi and Huffman.

Khami appears to have developed independently from the earlier Leopard’s Kopje Culture. This also questions the validity of the linear model used to explain the origins and development of Zimbabwe Culture as outlined in the paragraphs above. Rather than states developing in a hierarchical manner we should see them as multiple states developing at roughly the same time and co-existing and equally engaged in the trade network with the East African coast.

These results came from their excavations away from the elite platforms at Khami and so they conclude that archaeologists should examine and excavate a far wider area of sites like Khami in future rather than concentrating only on ‘elite’ areas as the ‘commoner areas’ show contributed significantly to our knowledge of precolonial states in present-day Zimbabwe. they played a significant role.

Khami Site Museum

Here you purchase entrance tickets – make sure you get a receipt. This has a small, but comprehensive display and is certainly worth a visit to get yourself orientated.

The Hill Complex

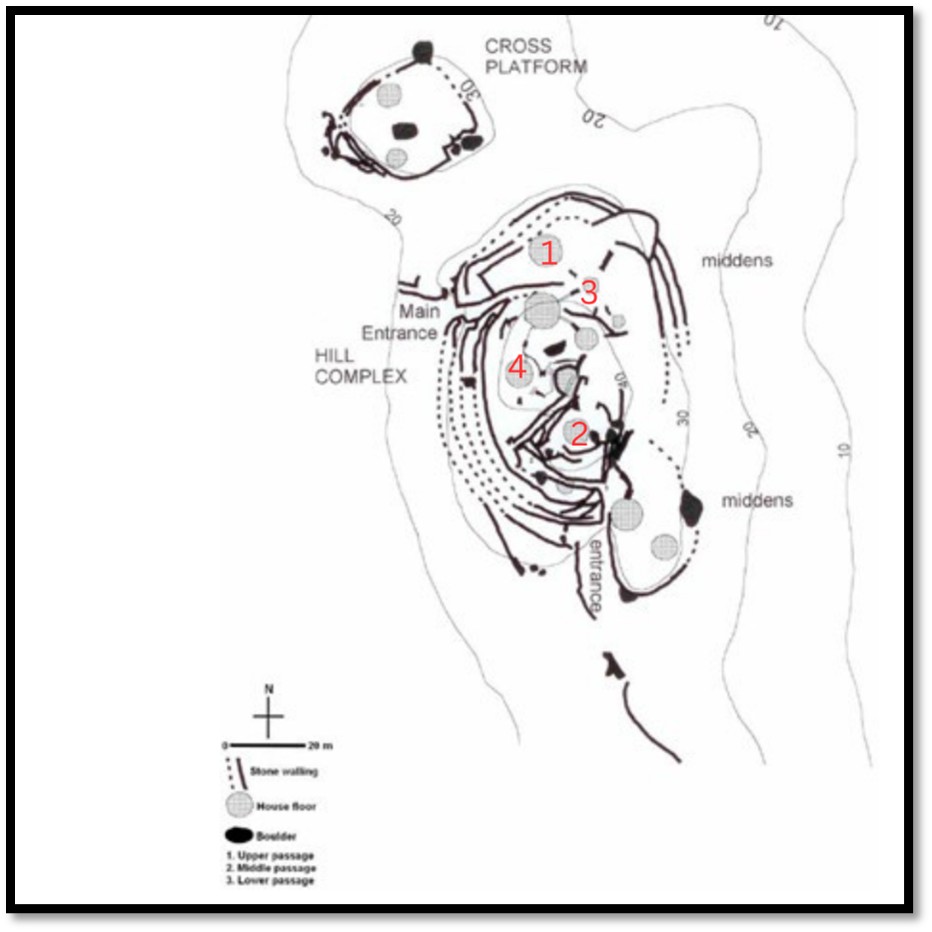

This area includes the (1) main platform (2) cross platform and (3) north platforms.

Google Earth view of Khami with important features marked

Key

1 = Site Museum

2 = Main, Cross and North Platforms

3 = Vlei Platform

4 = Precipice Platform

5 = Passage Platform

6 = Monolith Platform

- Main platform

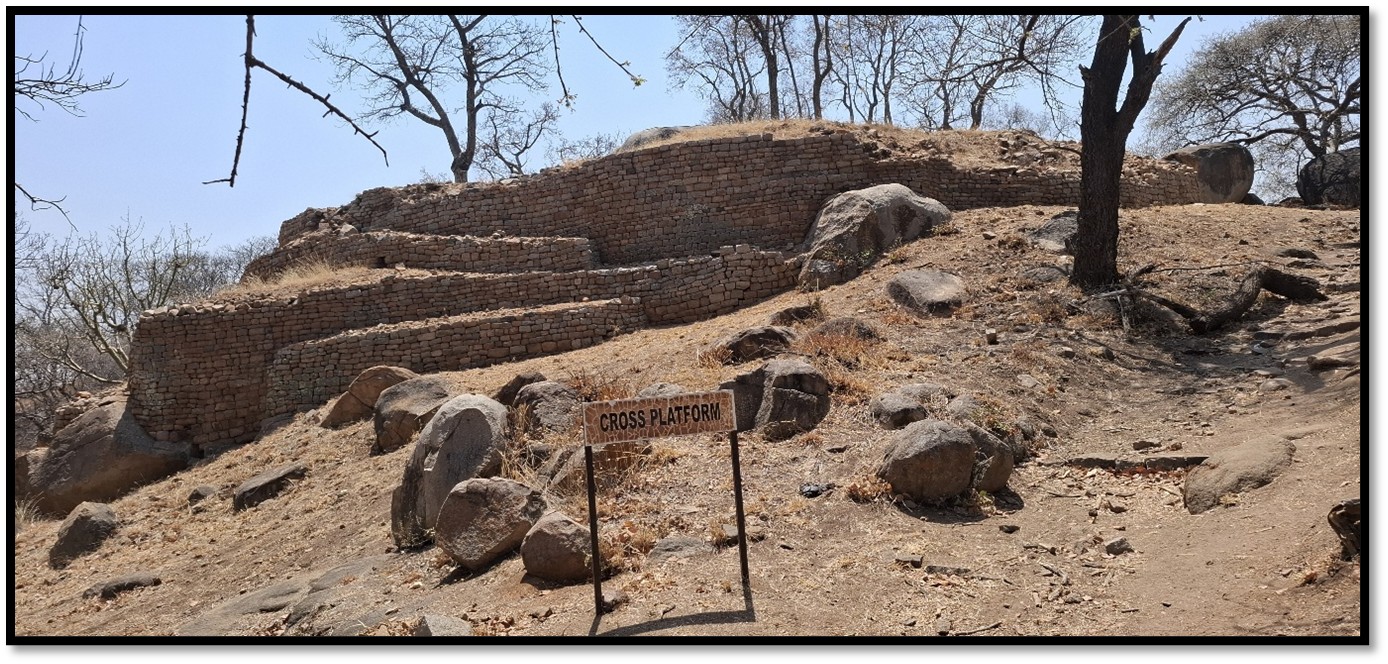

The imposing tiers of the Hill Complex at Khami

The imposing tiers of decorated dry-stone walling indicate the front of the main Torwa residence and are the most photographed image of Khami. The open area in front may have been the royal court with a small platform on the east that may have been from where the ruler presided.

Graphic of the Hill Complex with the Mambo’s residence and court

From the base the main entrance leads via a sunken passageway to the summit of the platform. An alcove on the right was probably for royal guards. The replacement stone steps are on top of the original stone and dhaka steps and the sunken passageway probably originally has a thatched grass roof. Some of the wooden mopane posts placed in wall niches were present in the 1890’s.

The sunken passageway leading to the summit of the Hill Complex

From the platform summit the Khami river pools directly below were known as Isiziba seNgwenya “pool of the crocodiles.” There were at least seven, probably more circular pole and dhaka huts on the main platform. The large hut that had an internal dividing wall (1 on the diagram) was probably the Mambo’s audience chamber that was reached by steps from the sunken passageway and had a door on the opposite side that gave access to the Mambo and court officials. The space between the audience chamber and walling may have been the royal court where official matters were discussed.

The hut on the highest part of the platform may have been the Torwa Mambo’s own residence (2 on the diagram)

The summit of the Hill Complex with the Rule’s residence on the right

A small hut may have been used for ceremonial or daily rituals as a zoomorphic pot[8] was excavated at this spot (3 on the diagram) where the Mambo may have requested guidance from his ancestors or in rainmaking ceremonies and is now housed in the Khami Site Museum.

A semi-underground hut is at the start of what once was a stone-lined dhaka roofed passage that may have been for prestige visitors seeing the Mambo (4 on the diagram) On the steps the archaeologist Keith Robinson found bronze and iron weapons in his 1947/8 excavation that were most likely for ceremonial occasions. Other finds included two small carved ivory lions and ivory divining dice or hakala. Further along the passageway a sunken room with dhaka covered walls had two decorated stones in the wall and once had an upright ivory tusk indicating it may have been a storehouse. At the end of roofed passage on a lower tier are the remains two or more dhaka huts that may have house court officials.

The once covered passageway and the semi-underground hut

Reconstructed dhaka entrance and walls

At the lowest level platform were more dhaka huts that may have housed junior wives or court officials.

Excavations in the midden below and on the river-side the main platform revealed large quantities of ash, broken pottery and iron tools, glass, ivory and shell beads, grinding stones and fragments of gold objects.

At the base of the main platform are large unworked dry-stones, sometimes called the megalithic wall. These were inserted at some time in Khami’s history to prop up the walls of the main platform that may have been about to collapse.

Present-day archaeologists argue that “A near exclusive focus on the stonewalled areas created a general misconception that the non-walled sections of the site had a dearth of ‘exotic’ and ‘prestige’ goods. Consequently, this led to their designation as commoner zones that contrasted with exotica-rich stonewalled platforms.”[9]

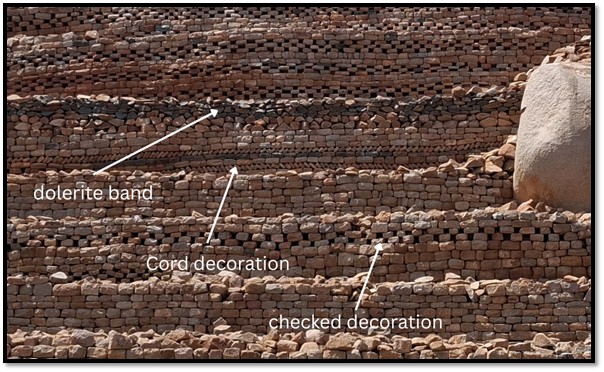

Types of dry-stone decoration on the Hill Complex

- Cross platform

Excavations on the cross platform revealed at least three large dhaka huts, the platform is better known for the Dominican Cross now cemented in place. Various romantic theories exist for its origin including that it is evidence of Portuguese missionary presence in 1644 or a priest’s burial or a recent addition.

Cross platform

Many visitors today leave offerings of money between the stones.

The Dominican Cross shape in stone

Off the cross platform the open area probably once marked a royal cattle kraal as excavations here revealed cattle dung. Only a few cattle would be held here…most were under the care of headmen at surrounding locations.

Rough stone terraces on the low ridge overlooking the Khami river may have been the royal kitchen area

- North platform

The ruined walls have some fine checked patterns using darker dolerite to contrast with the lighter granite. It is not possible to say what the original function of this platform was, as sadly this area was completely destroyed by W.G. Neal and G. Johnson, two prospectors who established a company, Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Ltd and in September 1895 the British South Africa Company (BSACo) granted the company, “the exclusive right to explore and work for treasure” in several ruins in Matabeleland and, “the first right to work further ruins.” Initial shareholders were Maurice Gifford, Jefferson Clark, Tom Peachy, W.G. Neal, George Johnson and Frank Leech. Neal and Johnson agreed to do the actual exploration and digging. In return for the concession, the BSACo would have 20 per cent of all finds and that “Mr Rhodes on behalf of the BSACo [would have] the first right of purchasing any discoveries.” Great Zimbabwe was excluded from the company’s activities.

North platform

Rear of the North platform – the platform tiers very obvious here

Following the Matabele (Umvukela) and Mashona (First Chimurenga) rebellions, another fifty ruins were dug up from September 1897 to May 1900 when the company ceased operations. However, apart from Chumnungwa and M’Telegewa Ruins, where a total of 178 ounces of gold were recovered, the company records reveal only small amounts of gold were found. But growing public awareness of the irreparable damage the company was doing to prehistoric remains put a stop to its operations.

There are other platforms and hut remains along this low ridge, but currently they are inaccessible to the public. He low dry-stone walls between them may have marked the perimeter of the royal zone.

The Vlei platform

The Vlei Platform is named for its low, marshy location near a vlei (wetland) area. It is one of several elite platforms built around the central royal complex and features free-standing stone walls, the remains of two dhaka huts with the remains of grain bins and two dry-stone walled enclosures which archaeologists think may have been used to house cattle or small stock.

These houses probably served as the residences for lesser rulers or elite officials of the Torwa state.

In one of the enclosures was excavated a unique ivory figurine of a man found within the small enclosure and now on display in the Natural History Museum in Bulawayo.

Some archaeologists have suggested that the vlei platform may be of later construction, possibly by the Rozwi when they occupied Khami, but this is still undecided.

Garbutt and Johnson 1912. Plan of a typical Khami hut with its various compartments

Precipice platform

From the Khami river dam[10] a narrow path leads to the Precipice platform. The platform is situated on a low ridge next to the Khami River and is surrounded by water on three sides. This is an exceptionally long retaining wall, the longest of its type known in Zimbabwe, with a check decoration along its whole length. Originally constructed with two levels, the lower level is now partly submerged by the reservoir.

The wall is 6 metres high (about 20 feet) by 68 metres long (about 223 feet) and may have been a ritual centre. Like the other platforms at Khami, it was an artificial, terraced area that supported dhaka huts and courtyards where people lived. At the northern end is a large walled enclosure with the remains of dhaka huts on a raised platform behind.

A balancing granite boulder near the dam wall which makes a bell-like sound when the cupules in the rock gong are struck surely formed a part in ceremonial occasions taking place on the Precipice platform. The Passage platform may have been reserved for the initiation ceremonies of young women.[11]

Passage platform

The Passage platform consists of two adjoining semi-circular platforms accessed by a narrow central passageway 18 metres (59 ft) long and decorated with lines of darker dolerite stones to contrast with the lighter granite. On excavating the platform the remains of a large dhaka hut, grain bin foundations and cattle enclosure were found suggesting a residential use by a court official.

A well preserved Tsoro game board is carved into the rock nearby.

Monolith platform

Close to the access road is one of the small outer platforms constructed around the central royal structures at Khami. A well-built dry stone retaining wall is the main feature. Like many of the other platforms excavations revealed the foundations of dhaka huts and a small cattle enclosure. It was most likely the residence of one of the lesser elite at this capital of the Torwa state. The monolith is an entirely natural stone feature around which the platform was built.

Khami Monolith platform

Spatial organisation at Khami

Circular platforms housed the residences of the elite residence at Khami. They had dry-stone walls enclosing their dhaka huts often made with inner and outer rooms showing a complex spatial organization reflecting their status. Outside their walls the commoners had their huts and carried out their activities, this was all part of a growing capital at Khami where the elite platform structures became more dispersed over time.

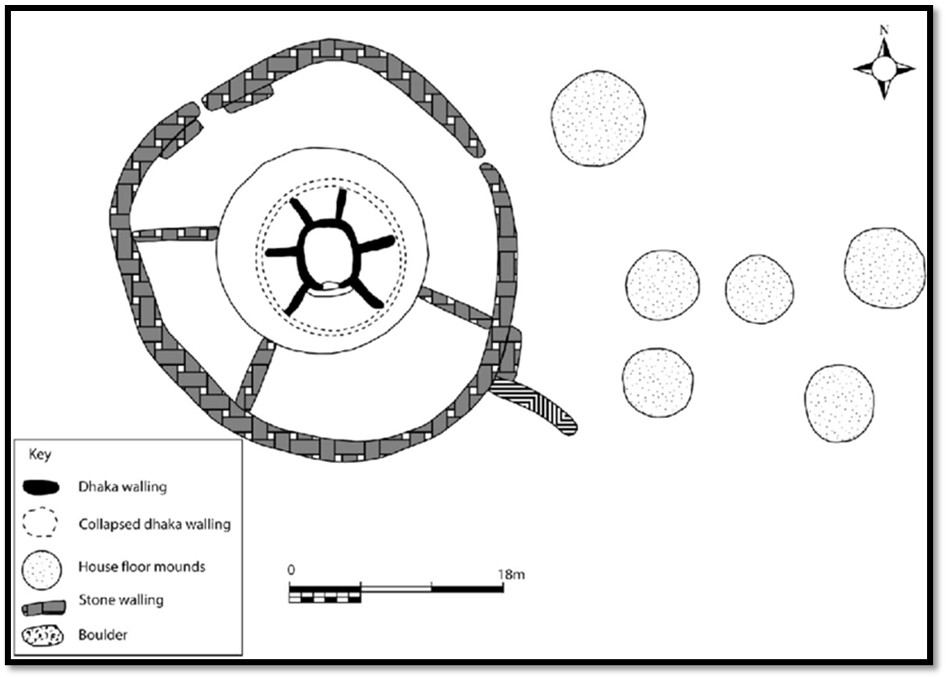

Spatial Organization of the Circular Platform[12]

The elites huts were built on the major walled platforms housing the rulers and court officials with surrounding areas outside the walls housing the commoners.

Inner Core: at the nucleus of the platform was a large central circular room, about 20 feet in diameter, serving as the main living / assembly space.

Compartmentalization: An outer circular wall was built around the central room, with radial walls creating smaller, private apartments or functional rooms, forming complex, multi-component houses.

Associated Structures: The platform supported a number of huts connected by stairways, passages, and terraces.

Khami: plan of the Circular platform showing the organisation of space within and around the platform[13]

Organization Within and Around the Platform

Space within the platform itself was organized with more private areas for the elite in the inner areas and more domestic functions on the outer edges, reflecting social hierarchy.

Around the Platform: important walled platforms like the Hill Complex, Cross, Passage platforms were scattered around Khami, indicating the capital's expansion.

Non-Walled Areas: Extensive unwalled settlements outside the platforms housed the commoners with archaeological excavations showing there was an initial dense concentration near the Hill Complex succeeded by later outward growth.

Material Culture: Elite goods, such as glass beads, ceramics and gold artefacts were found in both walled and non-walled areas, suggesting production occurred outside just the wall presence.

Other archaeologists, such as G. Hughes, have called into questions Huffman’s spatial organisation theory between ‘élite areas’ and ‘commoner areas’ based on housing structures.[14]

References

Natural History Museum. Khami Ruins Or Khami World Heritage Site. https://naturalhistorymuseumzimbabwe.com/khami-ruins/

R. Burrett & P. Hubbard. Khami Capital of the Torwa State. Khami Press, Bulawayo 2013

T. Makwende et al. The chronology, craft production and economy of the Butua capital of Khami, southwestern Zimbabwe. Azania Archaeological Research in Africa 2018, Vol. 53, No. 4, 477–506 https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2018.1540217

Notes

[1] See the article Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe at Bulawayo under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[2] The chronology, craft production and economy of the Butua capital of Khami, southwestern Zimbabwe, P481

[3] Khami, Capital of the Torwa state, P3

[4] The chronology, craft production and economy of the Butua capital of Khami, southwestern Zimbabwe, P477

[6] The Rozwi state (or Rozvi) was a powerful Shona state in Southern Africa, believed by many archaeologists to have originated in the Mutoko area in the 1600’s, famed as fighters from Shona kurozva, "to plunder." Under Changamire Dombo they controlled the gold trade on the Mashonaland plateau, successfully repelled the Portuguese and overcame the Torwa state before being defeated by the amaNdebele in the 1830’s.

[7 In 1693 Dambarare was destroyed by Changamire Dombe, See the article Dambarare – an Afro-Portuguese Feira site under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[8] The zoomorphic pot is shaped like an animal, possibly a sheep or goat, and likely used in rituals, possibly rainmaking ceremonies.

[9] The chronology, craft production and economy of the Butua capital of Khami, southwestern Zimbabwe, P478

[10] The Khami river dam was built in 1928 and was Bulawayo’s main source of water at the time

[11] The chronology, craft production and economy of the Butua capital of Khami, southwestern Zimbabwe, P481

[12] Ibid

[13] The chronology, craft production and economy of the Butua capital of Khami, southwestern Zimbabwe

[14] Hughes, G. 1997. “Excavations from the peripheral area of settlement of Khami.” Zimbabwea 5, P3–21