Great Zimbabwe, a UNESCO World Heritage Cultural Site

- A UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986 and one of Zimbabwe's main tourist attractions.

- The stone structures at Great Zimbabwe are the largest in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Centrally located, easy access on good roads and convenient to for overnight or longer stays.

- A large number of attractive and inspiring views of the ruins and set in a scenic location.

- Open throughout the year.

From Masvingo take the A4 towards Beit Bridge. Directions are from the railway line, immediately before the Masvingo / Great Zimbabwe Publicity Association. 1.42 KM proceed directly over the road junction, 4.31 KM turn left at signpost for Great Zimbabwe, 27.30 KM turn right at National Monuments sign for Great Zimbabwe, 28.2 KM reach entrance.

GPS reference: 20⁰16′08.84″S 30⁰55′42.70″E

Great Zimbabwe is undoubtedly sub-Saharan Africa’s largest and most imposing early dry-stone monument and over the years it has attracted much controversy over its purpose and the origin of its builders. The theories pre-1930 tended to favour an ancient and foreign origin; but as more and more scientific archaeology has taken place it has become much clearer that its builders were local and African in origin.

Unfortunately early excavations were completely unscientific as the ruins became associated with gold finds and much early exploration at Zimbabwe was done by adventurers simply fossicking for gold and “treasure.” Consequently, the stratification of the Great Zimbabwe site, and many others, was completely disturbed and many artefacts of great archaeological value, but with little intrinsic value, such a ceramics and pottery, weapons, ornaments and household items were simply discarded by these treasure hunters. Early well-meaning conservators rebuilt the walls which had largely collapsed, but paid little attention to the underlying deposits; consequently in 1958 the Historical Monuments Commission prohibited all further excavations for the next twenty-five years, although much damage had already been done.

Another problem, referred to by Peter Garlake in Great Zimbabwe regarding the origins of Great Zimbabwe, which muddied the waters still further, was that many of the early archaeologists has little experience of working in Africa and took little account of the wealth of local historical, traditional and anthropological data available locally.

Background and Excavations

Portuguese traders heard about the remains of an ancient city in the early sixteenth Century and records survive of interviews and notes made by them, linking Great Zimbabwe to gold production and the long-distance trade. Antonio Fernandes, the first European explorer in Zimbabwe, travelled too far north to have encountered Great Zimbabwe, although he probably heard accounts and rumours of it.

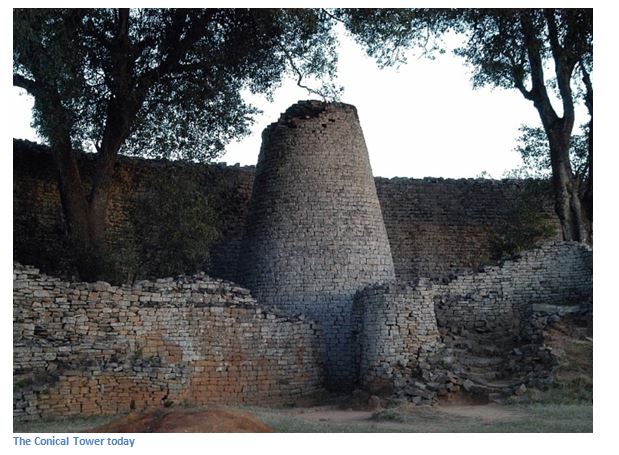

The earliest known written mention of Great Zimbabwe is by the Portuguese Vicente Pegado in 1531 who wrote: “Among the gold mines of the inland plains between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers there is a fortress built of stones of marvellous size, and there appears to be no mortar joining them…. This edifice is almost surrounded by hills, upon which are others resembling it in the fashioning of stone and the absence of mortar, and one of them is a tower more than 12 fathoms (22 metres) high. The natives of the country call these edifices Symbaoe, which according to their language signifies court.”

Much later Adam Render, a hunter, trader and prospector, in 1867 was on a hunting expedition from his home in the Soutspanberg across the Limpopo River in South Africa and was the first European to see Great Zimbabwe. Render soon after deserted his wife and children in 1868 and moved north of the Limpopo and lived about 20 kilometres south-east of Great Zimbabwe with the daughter of a local chief for the rest of his life. In 1871, the German explorer and geographer Karl Mauch, who had heard rumours of Great Zimbabwe, came to the area and stayed with Render for nine months and together they visited the ruins several times. Mauch sent descriptions of the site to colleagues and German newspapers, so initially many believed it was he and not Render, who found Great Zimbabwe.

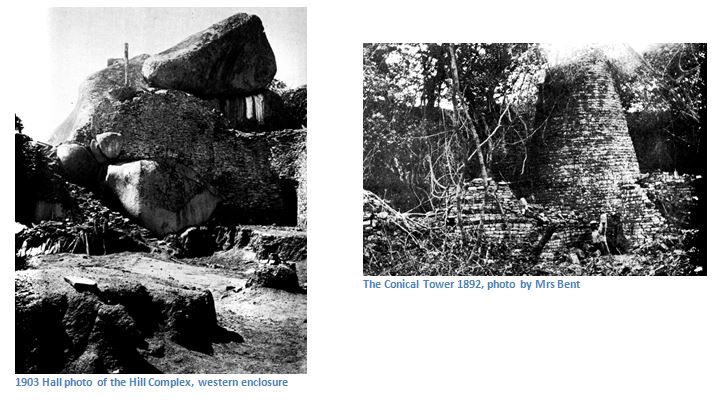

In a letter written in September 1871 to the Rev. Mr. Gruetzner, Mauch describes Zimbabwe in these terms: “The western side of this mountain is covered from top to bottom by the ruins. As they are for the most part fallen in and covered with rubbish, it is at present impossible to determine the purpose the buildings were intended to serve; the most probable supposition is that it was a fortress impregnable in those times, with the many passages— now, however, walled up…all the walls, without exception, are built without mortar, of hewn granite, more or less about the size of our bricks…best preserved of all is the outer wall of an erection of rounded form, situated in the plain, and about 150 yards in diameter. It is at a distance of about 600 yards from the mountain, and was probably connected with it by means of great outworks, as appears to be indicated by the mounds of rubbish remaining...Inside, everything excepting a tower nearly 30 feet in height, and in perfect preservation, is fallen to ruin, but this, at least, can be made out: that the narrow passages are disposed in the form of a labyrinth.”

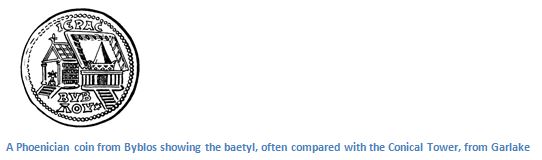

Karl Mauch began the speculation about a possible Biblical link with King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, an explanation which had been suggested by earlier writers such as the Portuguese Dominican Missionary João dos Santos. Mauch claimed a wooden lintel at the site must be Lebanese cedar, brought by Phoenicians and promoted the legend that Great Zimbabwe was built to replicate King Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem.

Theodore Bent, a rich English traveller and antiquarian who had travelled very widely in Arabia, Greece and Asia Minor, with his wife worked at Great Zimbabwe in 1891 with a surveyor R.M.W. Swan. He stated in the first edition of his book The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland (1892) that the ruins had been built by either the phoenicians, or the Arabs, as builders in ancient times. By the third edition of his book in 1902 he was more specific, saying the builders were "a Semitic race and of Arabian origin" of "strongly commercial" traders living within a client African city, but he did not link them positively with the Queen of Sheba.

However, other contemporary authors such as Hall and Neal had every reason to play down the fact that many of the everyday domestic objects found in the ruins were still in use by contemporary Shona, as indicted by the title of their book, The Ancient Ruins of Zimbabwe. The legend of King Solomon's Mines and the Queen of Sheba grew steadily from this academic source, although many writers had already pointed to modern day Zimbabwe as the only possible source in the ancient world of the large quantities of gold required for the First Temple in Jerusalem whose construction is credited to King Solomon.

In 1905 Archaeologist David Randall-Maclver in Medieval Rhodesia claimed the dwellings were “unquestionably African in every detail” and there was a storm of protest from those who had based their belief in a more ancient origin. Amongst the greatest barriers to the truth at the time were the following:

- Raiders and amateur archaeologists removed and damaged important artefacts which added an extra barrier to archaeological research, especially after Bent found gold beads and crucibles bearing traces of gold.

- The appointment of R.N. Hall as first Curator of Great Zimbabwe when in two years of continuous and indiscriminate digging, sometimes twelve feet deep, he destroyed much of the site stratified archaeological deposits. Contemporary archaeologists described his “reckless blundering” as “indescribable” and his “field work…worse than anything I have ever seen.”

- The Mfecane with its successive waves of invaders in the 1830’s completely muddled the collective memory of the local Shona living in the area. Early travellers to the site constantly record that local Shona had no knowledge of the early builders.

Early visitors to Zimbabwe comment on the almost impenetrable jungle that engulfed the ruins, now completely cleared away, so that the shape and form of Great Zimbabwe may be seen clearly. About 1912, it became necessary to take steps to prevent further disintegration of the buildings; the work of reconstruction was carried on for many years by Mr St C. A. Wallace, Curator of Great Zimbabwe.

In 1929 Gertrude Caton-Thompson was invited “to undertake a further examination of the ruins at Zimbabwe or any monument or monuments of the same kind in Rhodesia, which seems likely to reveal the character, date and source of the culture of the builders.” Her first test pits on the Hill Complex uncovered domestic pottery and ironwork. Further test trenches in the Great Enclosure and Valley Complex revealed more domestic pottery and ironwork, imported items and a gold bracelet. Her excavation work found foreign imported South Indian and Malayan glass beads of the eighth and ninth centuries, which were found below the original floors. On the original floor level of the buildings were found Persian porcelain of the thirteenth century, Chinese porcelain of the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and Arab glass, plain, enamelled and engraved, of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Local African made items were found both below and above the original floors.

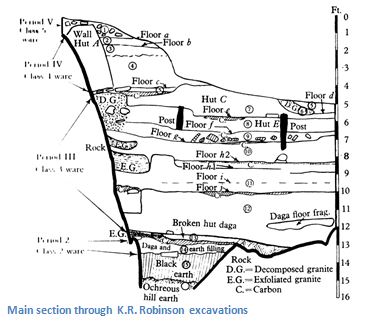

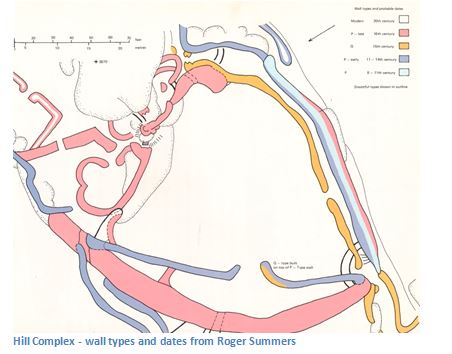

She thus confirmed Dr Randall-MacIver's argument that the stone buildings of Zimbabwe were the work of Africans. In 1958, Robinson excavated on the western enclosure of the Hill Complex finding undisturbed deposits which revealed daga hut bases, glass beads and potsherds reaching the very lowest deposits which revealed a layer of pole-impressed daga hut bases, thus confirming all of Caton-Thompson’s conclusions

In 1971 Roger Summers wrote Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilizations of Southern Africa and in 1973, Zimbabwe’s most eminent and locally born archaeologist Peter Garlake published Great Zimbabwe. Both authors reviewed all the evidence and agreed that the builders of Great Zimbabwe were a pastoral people who probably came from Mapungubwe in the Limpopo River valley. Major Construction started around 1100 and continued until 1450 AD. At the high point of Great Zimbabwe’s existence, it is said that more than ten thousand people lived here in mud and thatch huts in and around the massive stone walls. They raised cattle, mined for gold and copper, hunted elephants for ivory and traded with Swahili merchants on the East African coast, using the Save River route, as is evidenced by the artefacts of Asian and Arab origin that were discovered within the site.

A brief summary of the history as revealed by the Archaeological record

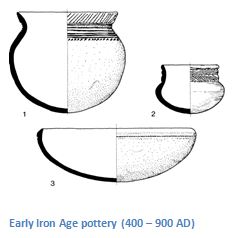

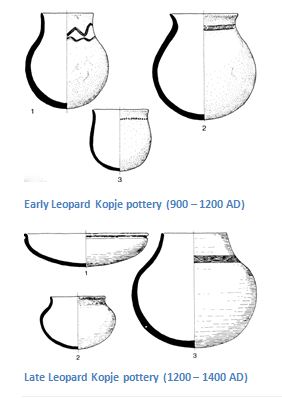

Evidence that Early Iron Age communities (400 to 900 AD) lived at Great Zimbabwe are found in the remains located in the lowest levels; ceramics, pottery figurines and pole-impressed daga from their hut remains.

From 1000 AD, with the advent of cattle, Great Zimbabwe developed from a few scattered pole and dhaka huts amongst the granite boulders of the Hill Complex into an increasingly large village with a Ruler who had power over the community and who commanded a skilled labour force capable of building the granite walls. The introduction of cattle and the development of trade around Great Zimbabwe enabled wealth to be accumulated and with it came a concentration of power. Although this development also took place elsewhere in Zimbabwe, Great Zimbabwe very probably also developed:

- As a major religious centre, indicated by the conical tower, monoliths, altars, soapstone birds and figurines.

- As a major trading centre from its central location. It lay on the edge of the major gold-producing areas of the Midlands and Matabeland and in a direct line with the East African coast through the Save River valley.

Between 1200 and 1300 AD a rapid expansion of wealth takes place and the focus of building moves into the Valley Complex and Great Enclosure. Great Zimbabwe appears to establish a virtual monopoly within Zimbabwe of this new found prosperity in the form of imports of ceramics, glass objects and beads with skilled craftsmen on site producing gold, copper and bronze ornaments and weaving and spinning.

The capital was abandoned in 1450, apparently due to overpopulation and deforestation; the kingdom split and moved west to establish the Torwa State around Khame and North to establish the Mutapa state.

All the radiocarbon dates are in support of occupation dates for Great Zimbabwe between 1100 and 1450, with the bulk of the dates in the latter period. The people living here spoke a Shona language and are descended from what is called the Gokomere culture and probably related to the Mapungubwe culture from the Limpopo River valley.

Great Zimbabwe site

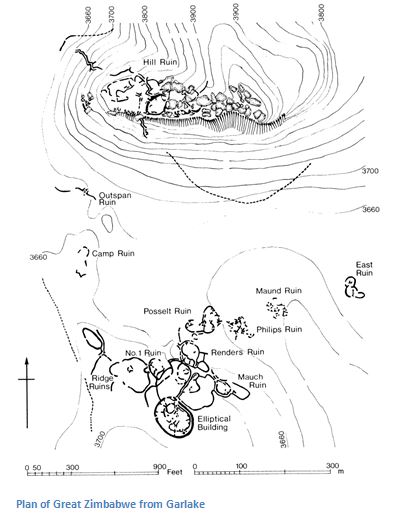

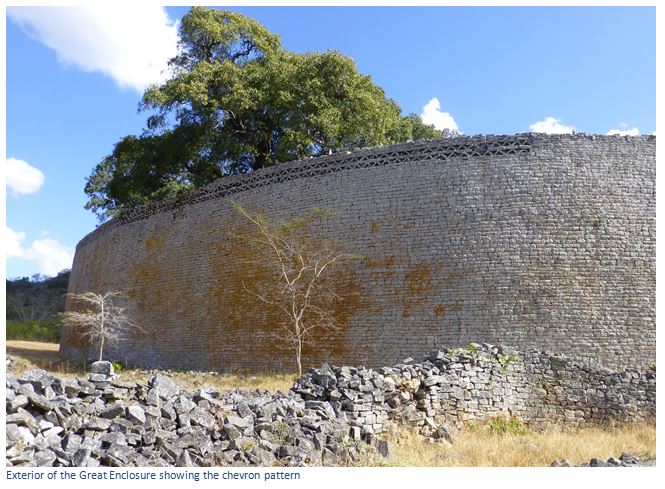

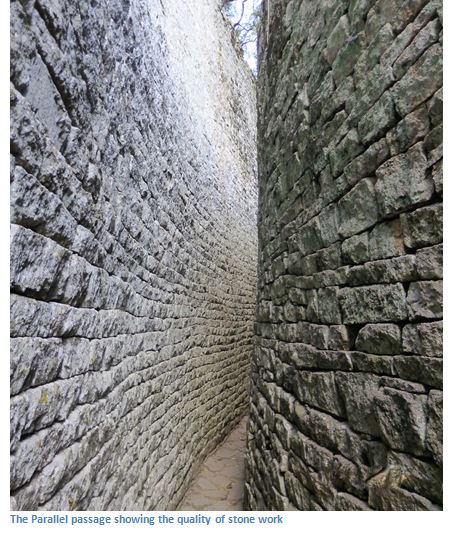

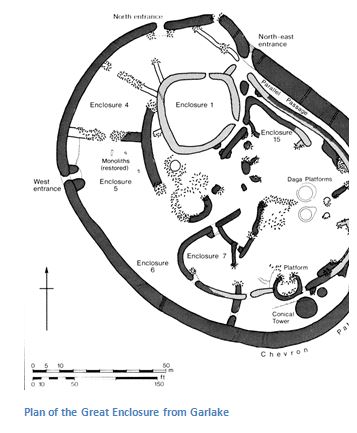

Spread over 720 hectares, it is an impressive array of dry stone structure made of hand carved granite blocks featuring chevron, herringbone and other intricate patterns. Most traces of the mud and thatch huts are gone, apart from the thick dhaka floors. The structures divide into three groups: -

The Hill (or Acropolis) Complex, a series of stone walled enclosures set among boulders at the top of an eighty metre high hill. Early architecture of the Hill Complex differs dramatically from later developments, showing progress of building style and technique and continual human settlement from 1000 to 1400 AD. Separate walled enclosures are accessed by narrow, partly covered passageways. The western enclosure was probably the residence of successive Rulers, their closest family and advisers and the eastern enclosure where six upright steatite posts topped with birds were found, probably served a ritual purpose.

The Great Enclosure - a massive wall in the form of an ellipsis, 255 metres in circumference, ten metres high and five metres wide in parts which surrounds the Conical Tower. The Tower is eleven metres tall and absolutely solid, its function is unknown, but some believe it to be a symbol of a granary. The walls are built of granite blocks, laid in regular courses and contain the remains of dhaka hut foundations, divided into separate living quarters by dividing walls. Here the wives of the Ruler resided, along with his counsellors and prestige items including fragments of soapstone bowls, porcelain, Arab glass and gold were found here.

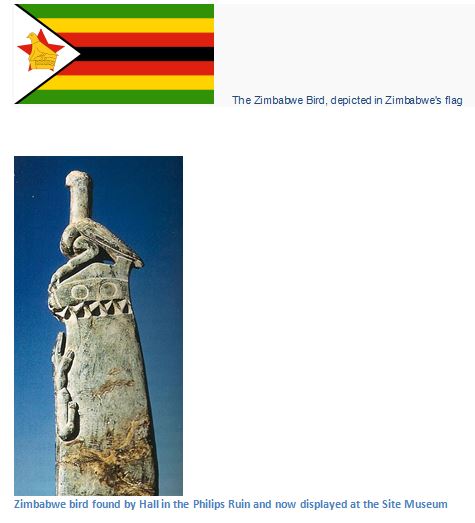

The Valley Complex is where the Zimbabwe Bird was found by Harry Posselt, the only soapstone bird discovered outside the Hill Complex and which may have been a royal totem and has been adopted as Zimbabwe's emblem and is now on display at the Site Museum. The ordinary people rather than the elite lived in this area of Great Zimbabwe. They comprise the numbered ruins one to three, the Maund, Phillips, Posselt, Renders and Mauch Ruins. Some were much robbed for stone and subject to the diggings of Hall and Sir John Willoughby; the Maund Ruins were excavated by Caton-Thompson and much knowledge gleaned on building techniques. An excavation by Elizabeth Goodall in 1943 revealed a great quantity of glass and gold beads, possibly the stock in trade of a Swahili merchant. Roger Summers states these Valley Ruins have not been as thoroughly restored as the Hill Complex and Great Enclosure, thus revealing more about building techniques as a result of this apparent neglect.

The Great Zimbabwe Site Museum on site displays some of the artefacts unearthed by archaeologists including the soapstone Zimbabwe birds which serve as the national emblem of Zimbabwe, although the poor lighting and very intrusive security presence somewhat lessens their impact.

Acknowledgements

K. Mauch. Edited and translated by F.O. Bernhard. African explorer. Struil 1971.

J.T. Bent. The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland. London 1893.

D. Randall-Maclver. Medieval Rhodesia. London 1906.

G. Caton-Thompson. The Zimbabwe Culture. Oxford 1931.

R. Summers. Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilizations of Southern Africa. Cape Town 1971.

P.S. Garlake. Great Zimbabwe. Thames and Hudson 1973.

Wikipedia