The death of Cecil John Rhodes at his Muizenberg cottage in 1902

Rhodes in 1901

From March to May in 1901 Rhodes was at Kimberley overseeing De Beers business and resting. He wrote to Alfred Milner[1] saying, “My heart is dickey, so you like to put your house in order.”

The Second Anglo-Boer War[2] was underway. The Boers, despite being outnumbered, fought very effectively using guerrilla tactics, making it difficult for the British to establish control. The British suffered heavy casualties and In response, under the command of Lord Kitchener, throughout 1901 adopted increasingly harsh tactics, including the establishment of concentration camps to house Boer civilians and their families, and the use of "scorched earth" policies, destroying farms and crops to deprive the Boers of food supplies.

Despite the possibility of Boer attacks, Rhodes took the train to Bulawayo from Kimberley and in June gave a major speech about the future of the country[3] saying that the British South Africa Company rule was “purely temporary” and that self-government was coming. In addition, he wished the settlers to get their house in order to be ready to enter a federation of southern Africa that he hoped would follow after the Anglo-Boer War, saying, “This great dominant North - including the Transvaal, will dictate the federation” and he also spoke of the grave he planned for himself and others in the Matobo.

Rhodes cottage at Muizenberg in 2025

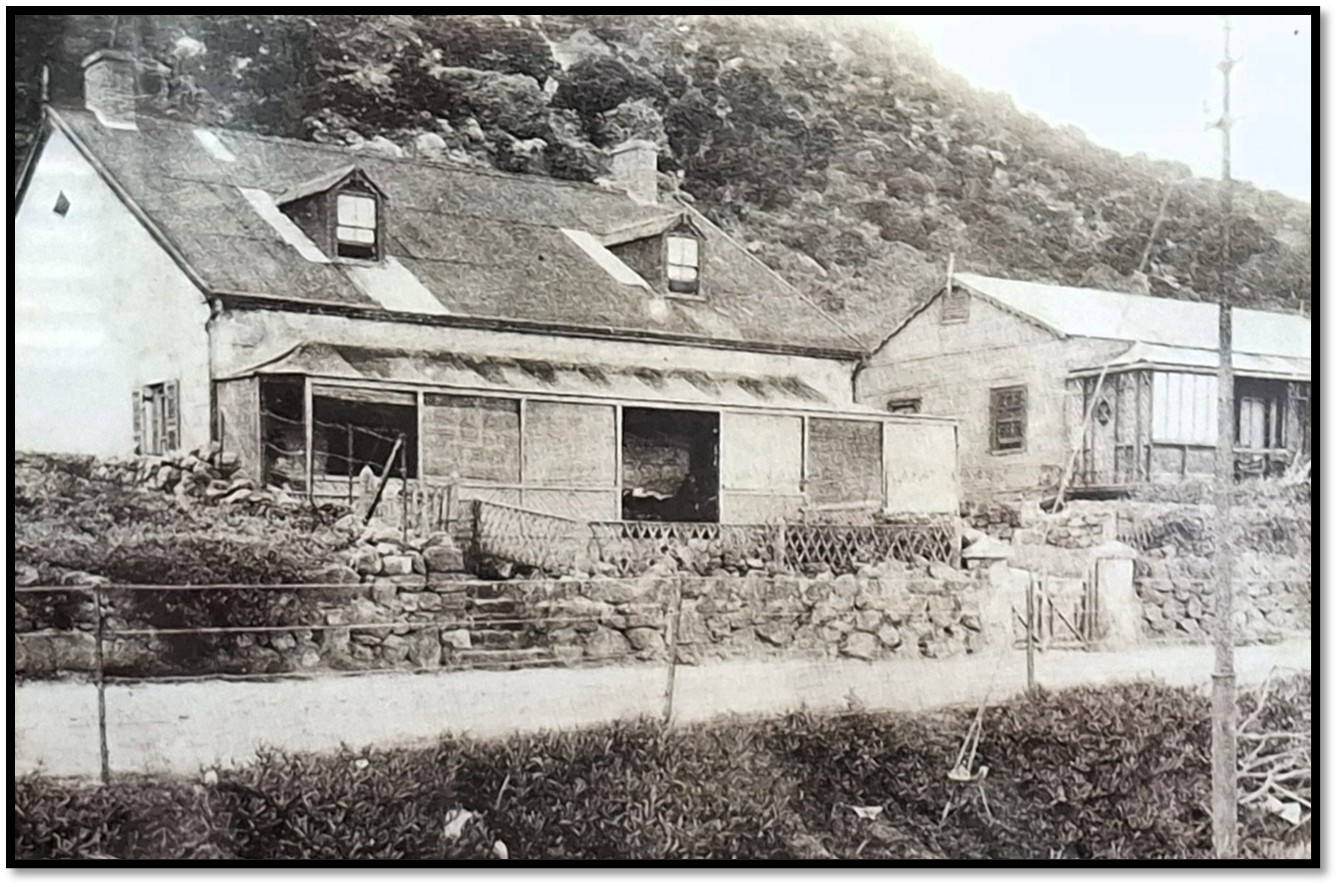

Rhodes cottage with corrugated iron roof in 1902 when he died on 26 March 1902

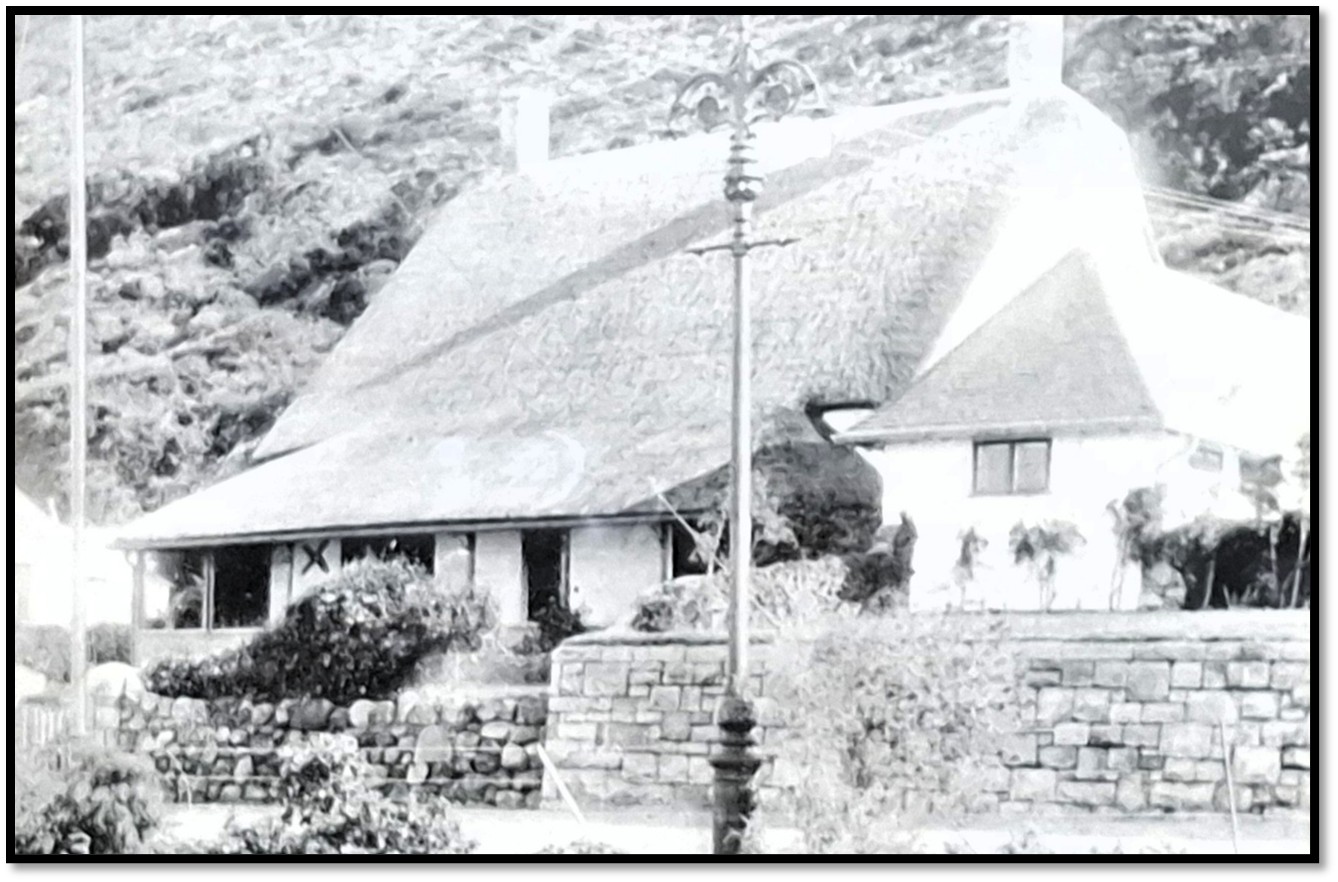

Rhodes cottage in 1911 with thatched roof

Philip Jourdan writes, “At Kimberley and Bulawayo he appeared to be in good health and was in excellent spirits; he went for his usual daily rides, and no one who saw him at that time could have imagined that he had only another twelve months to live. At Bulawayo he was particularly active. He frequently visited his farm in the Matoppos and also took excursions into the surrounding districts. When he was in the town he transacted business daily at the Administrator's office.”[4]

In late June 1901 he returned briefly to Kimberley and travelled onto Cape Town to begin planning the construction of a house at Saint James near Muizenberg. Then he sailed in July for Britain to deal with De Beers and British South Africa Company business. There he met with Alfred Milner who had just been appointed Administrator of the Transvaal and Orange River Colony and Alfred Beit[5] and was inducted into the Privy Council by King Edward VII. However, his most important appointment was with Sir James Kingston Fowler, his London physician, who advised a long rest and a constant change of surroundings. Rhodes heart remained weak and he supposedly asked Dr Jameson, “At any rate death from the heart is clean and quick, there is nothing repulsive or lingering about it; it is a clean death, isn't it?”[6]

Jourdan says, “It was most pathetic to see and hear him solemnly utter these words. We all knew he was thinking about his own death. Dr. Jameson had not the heart to meet his eyes. He tried to give a casual reply to the question, but his voice betrayed his emotion. Rhodes noticed it, but instead of being depressed, by a wonderful exercise of will-power his face lighted up and he laughed away the incident.”[7]

A collection of Rhodes memorabilia at his Muizenberg cottage

During August and September, the grouse hunting season, he rented a house near Loch Rannoch in northern Perthshire and entertained close friends including Dr Jameson, James Rochfort Maguire,[8] Philip Jourdan,[9] Sir Charles Metcalfe,[10] Alfred Beit, the Earl Grey[11] Gardner Williams,[12] Abe Bailey[13] and Winston Churchill. Sixty years later, Churchill recalled a holiday riding ponies, carrying guns, and engaged, “in various affairs, nominally sporting.” Jourdan reported, “Rhodes enjoyed shooting grouse, he was always very keen on getting a good bag and he revelled in the open life, and loved having his lunch on the heather, where he was always in good spirits and forgot all about his heart trouble.”[14]

But Frances Evelyn Maynard, the future Countess of Warwick, remembered Rhodes as too ill at Rannoch to join the shooting and fishing parties. She and Rhodes mounted hill ponies and trotted along the moors, “There we would dismount and let the ponies wander, while we sat and talked, he telling me of all his wonderful ideas…” He told her about the scholarship scheme, “his aim being to build up citizens of the Empire” and also of the empire, “which seemed much nearer to him than his own daily existence.” He spoke of it, “where another man would have talked of his family life, or his own predilections.”[15]

When she accused Rhodes of being a dreamer, he responded, “it is the dreamers that move the world. Practical men are so busy being practical that they cannot see beyond their own lifetime. Dreamers and visionaries have made civilizations. It is trying to do the things that cannot be done that makes life worthwhile. The dream of today becomes the custom of tomorrow. But if there had been no dream…we should still be living in caves, clubbing each other to death for a mouthful of food.”[16]

At the end of their talks, she would catch the ponies and bring the one that Rhodes was riding near some large boulder so he could mount with ease, “The slightest exertion made him breathless.” He would say, in a “touching child-like way…that he was sure that God would not let him die before he done his work…” bringing the union of southern Africa into being.

From Perthshire, Rhodes travelled with Jameson, Beit, Metcalf and Jourdan to Paris and Lucerne and then to Italy to the saline baths at Salsomaggiore that were said to be beneficial for inflammatory disorders.[17] After a week there they travelled onto Bologna, Verona and Venice and then sailed to Port Said to board a Thomas Cook vessel on the Nile. Rhodes wrote to Michell[18] saying, “I am better. The heart has quieted down, although I still have pain, which they say is the enlarged heart pressing on the lung. The great thing is to rest.”[19]

Rhodes interest was, “the marvellous productive power of the …annual Nile flood...”[20] and the possibilities of irrigation in southern Africa rather than Egypt’s history and the Temples of Isis and Ramses. He wanted to sail to Wadi Halfa and then travel by train to Khartoum, but this plan was vetoed by Dr Jameson who believed the heat would be too much for Rhodes.

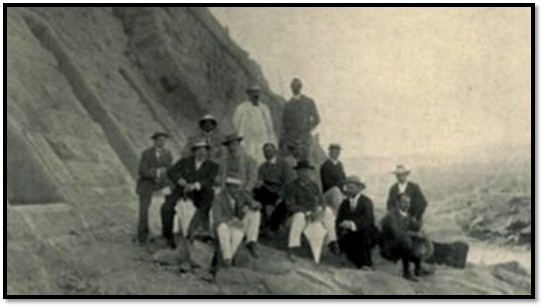

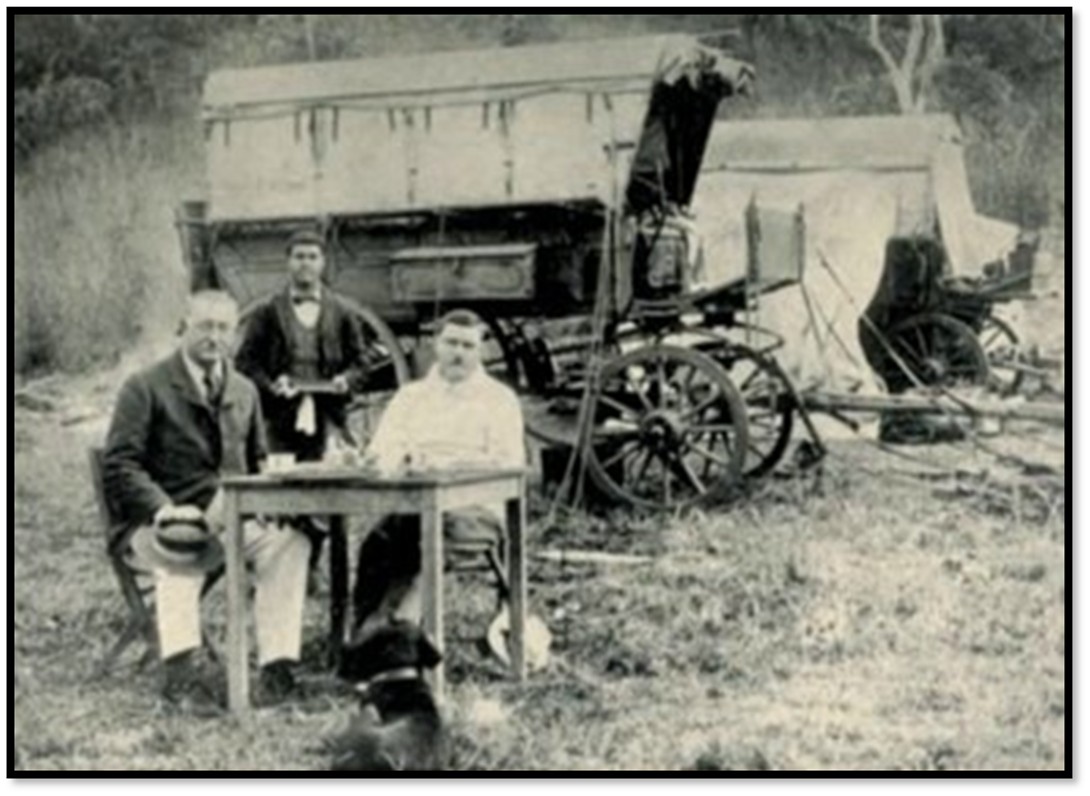

Jourdan: Cecil Rhodes and party at Aswan Dam

1902 – the last year

Gordon le Sueur[21] met Rhodes’ ship at London in the first week of 1902, “his face was bloated, almost swollen, and he was livid with a purple tinge in his face, and I realised he was very ill indeed.”[22]

In London Rhodes visited the studio and workrooms of John Tweed who was making the bronze panels for the monument to Allan Wilson and his comrades to be erected at World’s View (Malindidzimu) in the Matobo. See the article James Dawson’s account of finding the remains of Allan Wilson and his patrol under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Rhodes’ medical condition

Miles Shore states this description is consistent with a superior vena cava syndrome which was to become the major cause of Rhodes’ death.

In March there were daily telegrams from Dr Jameson to Bourchier Francis Hawksley[23] who then passed them onto Sir J.K. Fowler, his physician. They were sent in code so as not to disturb the market value of British South Africa Company shares. From the cables, Shore states it was clear that compression of Rhodes’ vena cava was caused by a large aneurysm, confirmed at his autopsy, of the thoracic aorta, the major vessel carrying fresh blood from the heart.[24]

The aneurysm created a blood-filled sac, “the size of a child’s head” which pressed on the vena cava, the vein returning blood from the head, neck, chest and arms. The result was blood backing up in all the tributary veins causing swelling of his head and face and purpling of the skin. The aneurysm also pressed upon his trachea and lungs causing difficulty in breathing.

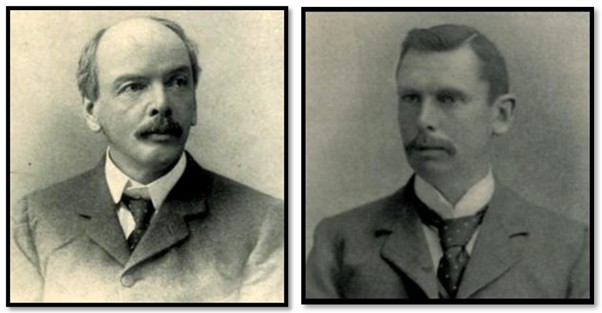

Gold Fields: Rhodes at Oriel, Oxford aged 24 NAZ: Rhodes circa 1900

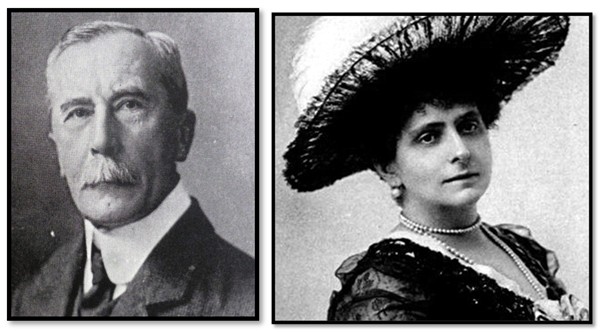

Rhodes and Princess Catherine Radziwill

Background to the Radziwill case

In July 1900, Radziwill had been having an affair with a building contractor named Harry Hindle. Harry and his brother James Hindle had ongoing building projects at Cape Town City Hall, Cape Town Castle, Groote Schuur and Rhodes' cottage at Muizenberg. (James and Harry were both at the cottage when Rhodes died on 26 March 1902.

Harry was unaware that Radziwill was secretly married with children and she probably assumed Harry’s association with Rhodes might be useful to her. However, she fell pregnant and the relationship with Harry Hindle ended in December 1900. To conceal her situation, she left her Kenilworth home and moved to a small house at Kalk Bay where her child, Alexi, was born in July 1901. She was now in financial trouble and forged several promissory notes on Rhodes. One forged note was for £4,500, another for £6,300 and another for £2,000.

When the forged notes drawn on Rhodes were revealed, Radziwill was arrested for fraud on 24 September 1901 but released on £114 bail the same day paid anonymously (Rhodes or Hindle?) until she was charged in the Cape Supreme Court. In her evidence, she stated that she had received the bills signed in blank by Rhodes from a Mrs Scholtz. However, there is no doubt that she forged the bills and then attempted to prevent any action being taken by threatening to publish compromising letters between Rhodes and Alfred Milner.

Rhodes learns of the forged notes

Jourdan writes, “It was whilst at Bulawayo that he received a telegram from Sir Lewis Michell asking him whether he had signed any blank promissory notes. He replied by wire to the effect that he had never given any promissory notes, much less blank ones. Sir Lewis then informed him that the Princess Radziwill was endeavouring to negotiate a note for £2,000. This annoyed him a great deal and he requested Sir Lewis to repudiate the document.”[25]

De Beers: Lewis Michell c. 1902 Wikipedia: Catherine Radziwill

At the time this concern was hushed up as a public trial of Radziwill for forgery would have interfered with his visit to England. Jourdan says, “The Princess wrote a nice note to him, wishing him a pleasant voyage, and at the same time sent him a book to read on the steamer. She made some excuse for not going to see him, but she apparently had not the courage to face him. I dreaded a meeting between them, as I felt sure a scene would have occurred that might have injuriously affected his heart. I was therefore very glad when her note came, which made it clear that she would not show herself at Groote Schuur.”[26]

In January 1902 Jourdan writes that Rhodes, “felt that, in view of the false statements that were being circulated in reference to his relations with her, it was imperative, in order to safeguard his good name, that he should return to South Africa to give evidence against her if necessary, otherwise it would immediately be said by his enemies that these libels were true, and that he knew them to be true. He said that one never knew what women of the character of the Princess were capable of. She might make any statement in his absence…”[27]

Despite the advice of Dr Jameson and all his associates, Rhodes decided to travel back to the Cape to give evidence against Princess Radziwill in the forgery case. He could have sent a statement, but Hawksley, his solicitor, had advised against it, not much liking the idea of sending medical evidence. He suggested that Rhodes could be examined and cross-examined in England before a commissioner. But Rhodes wanted to be in Cape Town to prevent new rumours and personally testify against any letters or documents that Radziwill might forge before the trial. Rhodes's reputation was in jeopardy and Hawksley cabled Michell that the trial, “must not be held without Rhodes’ evidence.”

The Trial of Radziwill - found guilty of fraud and sentenced

The Attorney-General Thomas Graham described her efforts as those of an ordinary blackmailer and that she had made use of her social position for purposes of intrigue and fraud. Her Solicitors, SilberBauer, Wahl & Fuller failed to convince the jury of her innocence in the twenty-four counts of fraud, including forging of Rhodes' name and signature.

Radziwill was sentenced on 14 November 1901 after three days of trial to two years at the Roeland Prison (without hard labour) where she occupied herself in writing but was released on 14 March 1903 after spending just sixteen months in prison. After her release from prison, she left the country and never returned.

Return to South Africa

On board the ship that took Rhodes to South Africa a bed was set up on the upper deck as he could not breathe in his cabin. Back in Cape Town he was at Groote Schuur during the day, but spent the nights at his Muizenberg cottage where he could catch the cool breezes from False Bay. Jourdan in his book Cecil Rhodes, His Private Life by his Private Secretary writes (P244) “The invigorating air at Muizenberg seemed to do him much good and he was always brighter and slept better when he was there.”

One of his tasks was to lead a parliamentary party to see the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, Sir John Gordon Sprigg, about the costs of defending the Cape. Afterwards, James Rose Innes, MP told his wife, “Really, I was shocked to see him [Rhodes] He has become stouter, and his face is a deep red and half again as big as it was when I saw him last. His breath also is very short. I understand that his heart is so dilated that it presses upon one lung, and that accounts for the flushed face and laboured breath…he really is a pathetic spectacle…”[28]

Jourdan says he asked, “Sir Edmund Stevenson to tell me his honest opinion of his [Rhodes] condition,” and I was staggered when he shook his head ominously and said, " I am afraid it is only a question of time." I said, " But surely, Doctor, you do not think that Mr. Rhodes will not live? " He replied, " We may be able to prolong his life for a little while longer, but you must make up your mind for the worst."[29]

Rhodes’ last month

Nights were spent in the little cottage at Muizenberg where he fought for each breath and said his heart “thumped.” Dr Jameson arranged for ice boxes to be put into the ceiling and ordered Indian type punkah fans and the windows were enlarged. In 1902 the cottage had a corrugated-iron roof. McDonald writes, “the intense heat of the sun beat down upon this iron roof which absorbed and radiated the heat for many hours after the sun had set so that even the air of the night seemed less cool than it would otherwise have been”[30]

Rhodes’ bedroom at his Muizenberg cottage

Dr Jameson and Sir Edmund Sinclair Stevenson, a Rondebosch physician, treated Rhodes with morphia for pain and digitalis and strychnine for his heart. He was also given oxygen for his lungs and they began trying gelatine (presumably nitro-glycerine) for his heart pains on the advice of Sir J.K. Fowler, despite Jameson and Stevenson’s concerns. His legs were drained of the fluid that kept accumulating from his increasingly failing heart. His urine was tested with albumin to keep track of his failing kidneys.

Jourdan: Dr Leander Starr Jameson Jourdan: Dr T.W. Smartt

Last days

Many of his friends made last visits. Dr Thomas William Smartt,[31] Sir Lewis Loyd Michell, Johnny ‘Jack’ Grimmer,[32] Edgar Walton, J.G. McDonald[33] Elmhurst Rhodes (a brother) with Jameson and Sir Charles Metcalf constantly present. Most were saddened by the sight of Rhodes “on the narrow stoep of that tin-roofed cottage.”

The narrow stoep of Rhodes’ cottage

James Rose Innes wrote that Rhodes, “sat, mortally stricken and in sore need of spacious and airy surroundings, one of the most famous and wealthiest men in the British Empire…I am glad of the wind because it will relieve Rhodes who suffers a great deal when there is no air…He is in a very bad way; and in the absence of some miraculous rally, I do not see how he can last much longer. His heart has taken a much worse turn of late and…now he is too ill to be moved even if he wanted to go.” There was, “something strange and pathetic…at seeing a man of his wealth breathing away in a miserably airless little box of a cottage; he will have no nurse or personal attendant; but Jamieson [sic] is very devoted.”[34]

Rose Innes reported a week later that Rhodes appeared, “about as bad as can be, the extreme weakness of his heart impairs the use of both lungs, and he is becoming dropsical. He sits up in bed day and night. I hardly think he can last long. He has gone steadily downhill during the last week.”[35]

From the 9 March Rhodes’ ill-health forced him to keep to his bed at the Muizenberg cottage. [36] McDonald writes that Dr Jameson’s, “endurance was a thing at which to marvel. He seemed to need neither food nor sleep and scarcely left his friend’s bedside. He watched over Rhodes with intense devotion and tenderness, the only rest he took was when he laid himself down for a few hours on a camp bed placed across the doorway.”[37]

Jourdan’s observations

Jourdan writes that Rhodes had great difficulty in breathing. He was most comfortable in an erect position and often sat on the edge of his bed with one leg on the floor, the other on the bed, his head sunk so low that his chin almost touched his chest. In the early morning and towards the evening when it became quite chilly, he did not notice the cold. Even when those around him were in overcoats, he sat in front of the open window in thin pyjamas. He was always asking for more fresh air, and eventually a hole was knocked in the wall opposite the window allowing the sea breezes to flow through the room.[38]

Philip Jourdan, Rhodes’ last private secretary Rhodes great colleague, Sir Alfred Beit

The Doctor’s reports

London telegrams to Sir James Fowler from Sir Edmund Stevenson read.

14 March 1902, “Lungs scarcely acting at all. Frequent attacks of heart failure only overcome by administration of oxygen.”

17 March 1902, “Stevenson says tell Fowler pressure on vena cava increasing rapidly. Cyanosis increasing, necessitating constant supply oxygen, otherwise getting steadily weaker.”

18 March 1902, “A fair night with a good deal of restless sleep. Lung condition certainly not worse for last two days, but dropsy now extended to abdomen.”

21 March 1902, “Lasted longer than we expected owing to extraordinary vitality but the end is certain.”

The End

Sir Lewis Michell sat by Rhodes’ bedside on the 26th of March. Jameson, “worn out by persistent watching day and night” took a nap. Rhodes was restless, Michell reported he murmured, “so little done so much to do.” After a long pause Michell heard him singing to himself, “maybe a few bars of an air he had once sang at his mother's knee.”[39] Rhodes was, “dying by inches.” He passed away at 6pm on 26 March 1902 aged 48 years 8 months.[40]

Jack Grimmer, before he died, reported that Rhodes spoke to him saying, “Turn me over, Jack” and then died.

The Cape Times reported next day, “eight minutes after six Mr Rhodes lost consciousness, breathing at the moment the name of his brother Elmhurst, who was amongst those gathered around the bed. Two minutes later he passed away peacefully and quietly, without so much as a quiver.”

The Autopsy

Dr Stephen Boxer Syfret performed the autopsy the same evening, observed by Stevenson, Jameson and Smartt. The major finding of the report confirmed the clinical diagnosis of a dilation of the ascending aorta “the size of a man's wrist” with a “secular dilation from the transverse portion as large as a child's head.” The descending aorta was also much dilated. There was no dangerous thinning of the aorta, nor any ulceration, such as one might see in a dissecting or about to rupture aneurysm. They aortic walls showed extensive arteriosclerosis.[41]

Miles Shore states the information supplied by the autopsy is insufficient to arrive at a single diagnosis to explain Rhodes’ nearly life-long health problems. He states, “the immediate cause of death was congestive failure of both the left and right ventricles of Rhodes’ heart. The size of the aneurysm makes it likely that the aortic valve, which prevents blood from regurgitating back into the heart, had become insufficient for its task. Thus, the heart was, at least intermittently, pumping ineffectively and leading directly to its ultimate failure.”[42]

He concludes, “the clinical course of his last illness and the autopsy findings do little to explain with any assurance the cause of his ‘heart attacks’ especially those in 1872,1877 and the 1880’s.”[43]

After

Rhodes’ body was taken to Groote Schuur the same night for the autopsy. The next day the whole British Empire appeared to be in mourning. Telegrams and cables of condolence were received from all parts of the world, flags were flown at half-mast and most businesses in Cape Town closed for the day. The Government announced a state funeral would be held.

The body lay undisturbed at Groote Schuur the following two days. On Saturday and Monday, the 29 and 31 March, the public were allowed access to Groote Schuur, where the coffin had been placed on a strong teak table. Tens of thousands of his friends and admirers came to pay their last respects. Many wreaths arrived from all parts of the world, including from Queen Alexandra, Lord Kitchener and Lord Milner.

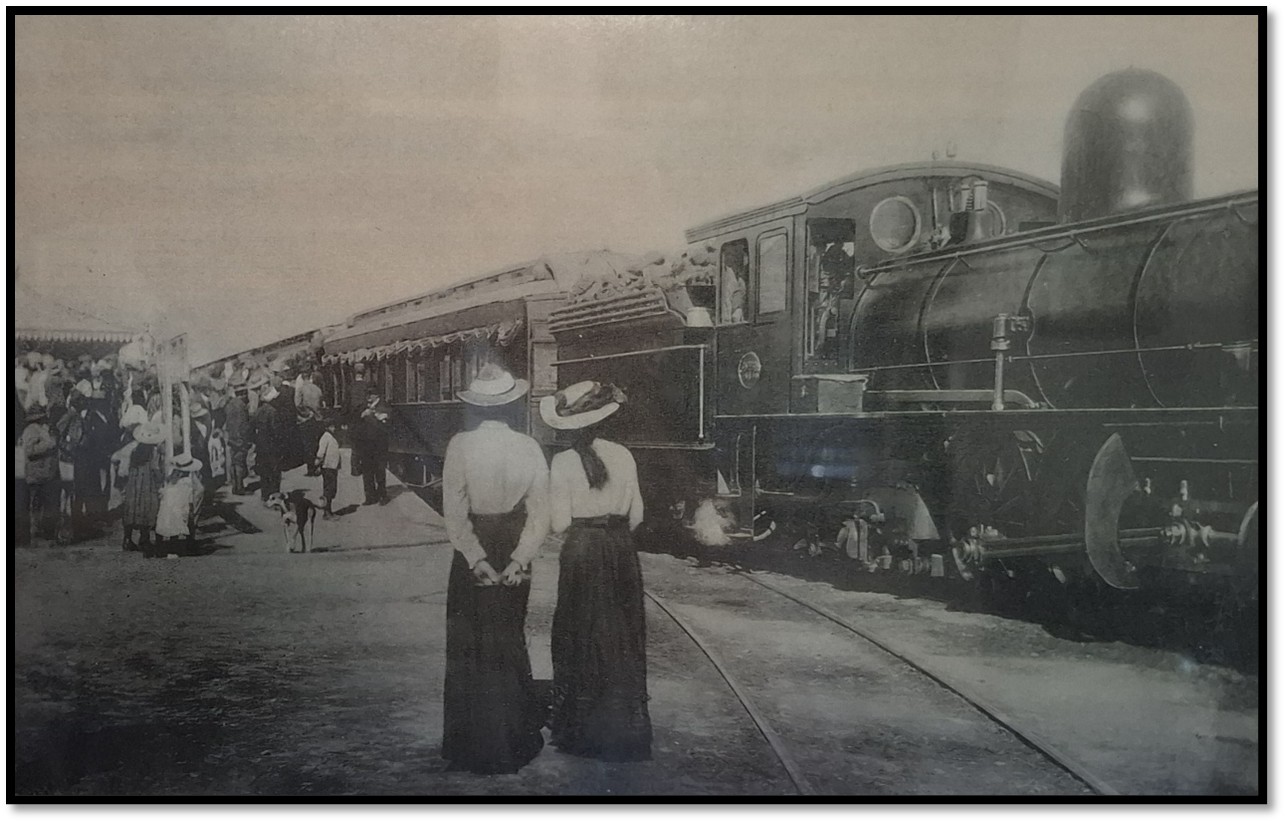

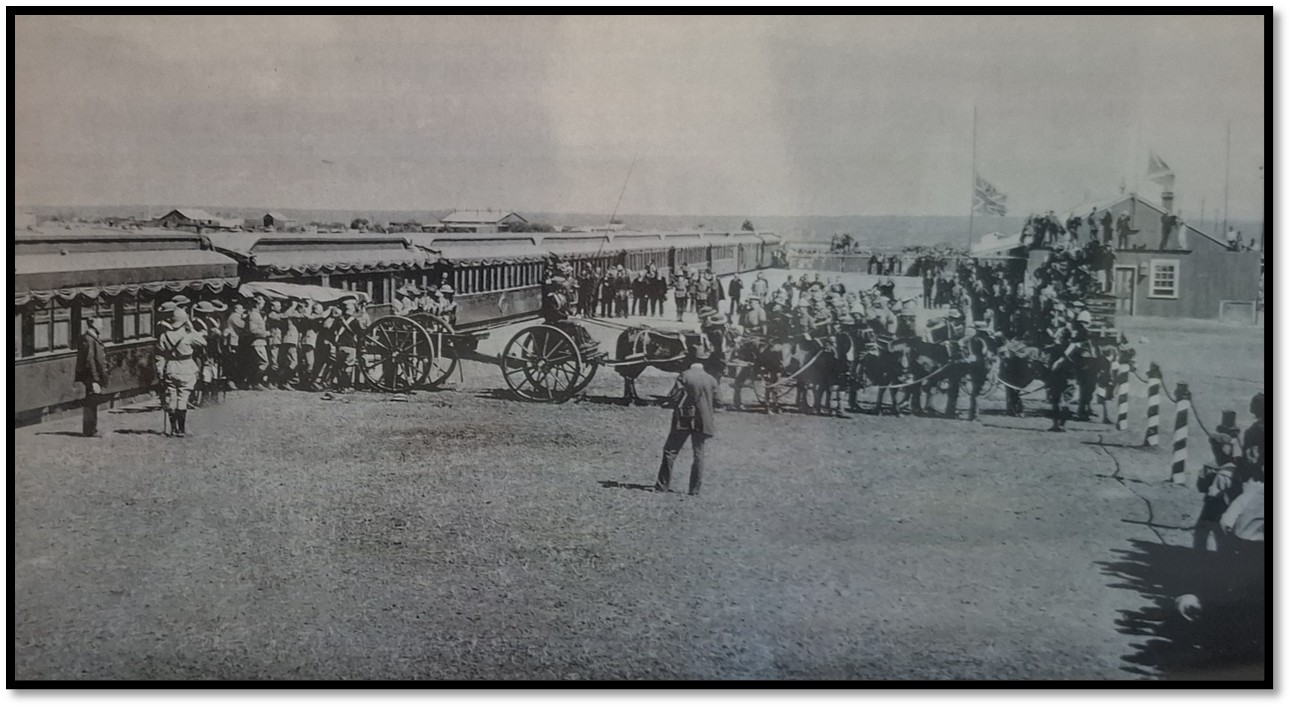

On 2 April the body was taken to Parliament and the following day again many tens of thousands paid their respects. About 1.30 pm on Thursday 3 April the coffin was taken in procession to St George’s Cathedral. The pallbearers being Dr Jameson, Sir Charles Metcalfe, Sir Gordon Sprigg, Sir Lewis Michell, Sir Edmund Stevenson, Dr TW Smartt, Hon. TL Graham, and Mr JB Curry. Following the funeral service the coffin was taken to the railway-station, where a special train was waiting to take the coffin and funeral party to Bulawayo where he was buried in the Matobo on the 10 April 1902.

Rhodes Cottage

The painting below shows Rhodes cottage on the left. The large house on the right named Rust en Vrede (rest and peace) was designed as a holiday cottage for Cecil John Rhodes by Sir Herbert Baker, the renowned local architect. Rhodes used nearby Rhodes Cottage (preserved as a museum dedicated to Rhodes' life and open to the public) as his temporary holiday house, but died in 1902 before Rust en Vrede was built. It was then bought by Sir Abe Bailey, who completed the building from the foundations upwards in 1904 according to the original plan and lived there until his death in 1940.

Rhodes cottage (left) and Rust en Vrede (right)

Rhodes cottage (left) and Rust en Vrede (right)

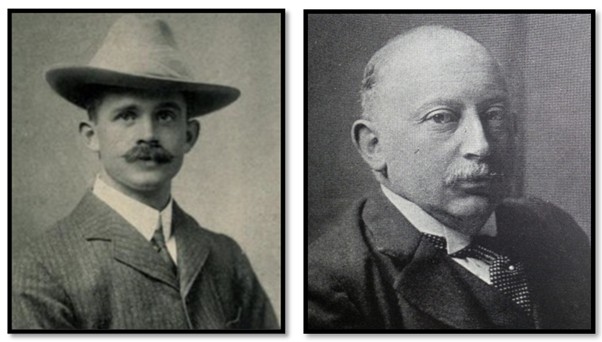

The Graphic: The Funeral train at Beaufort West

The Graphic: Departure of the Funeral train from Kimberley

The Graphic: The funeral train arrives at Bulawayo station

The train was draped in purple and black. “The coffin was carried in the old De Beers car in which Rhodes had so often worked and travelled…”[44] and reached Bulawayo on 8 April 1902.

References

Robert I. Rothberg with the collaboration of Miles F. Shore. The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power. Oxford University Press, 1988

Philip Jourdan. Cecil Rhodes, His Private Life by his Private Secretary. John Lane, the Bodley Head, London, 1911

J.G. McDonald. Rhodes: A Life. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo, 1971

[1] Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, KG, GCB, GCMG, PC (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a strong believer in British imperialism throughout his life. Following the Jameson Raid he was appointed by Joseph Chamberlain as Governor of the Cape Colony and High Commissioner for Southern Africa (5 May 1897 – 6 March 1901) He strongly supported British subjects in the Transvaal and Orange Free State and many writers assert his policies triggered the Second Anglo-Boer War. During the war, Milner received praise and criticism for his civilian administration in South Africa, including the establishment of concentration camps to intern the Boers. Following the British victory and annexation of the Boer republics, Milner was named their first British Governor.

[2] Also known as the South African War lasting from 11 October 1899 to 31 May 1902

[3] Initially the region was informally known as South Zambesia but the name "Rhodesia" came into use in 1895, after the British South Africa Company (BSAC) agreed to it in honour of Rhodes, who founded the company. By 1898, the area south of the Zambezi River was formally designated as Southern Rhodesia and in 1923 become the self-governing British Crown colony of Southern Rhodesia when the BSAC relinquished control.

[4] Cecil Rhodes, His Private Life by his Private Secretary, P245

[5] Alfred Beit arrived in Kimberley in 1875 to buy diamonds on behalf of Jules Porgès et Cie and quickly fell under the spell of Rhodes's talk of 'big schemes'. They became business partners and began to buy diamond mining claims of their rivals including Barney Barnato. Together they gradually gained control of the diamond-mining claims in the Central, Dutoitspan, and De Beers mines, Rhodes being the active politician and Beit providing the planning and financial backing. On 13 March 1888 De Beers Consolidated Mines was formed with Rhodes, Barney Barnato and Alfred Beit as directors.

[6] The Founder, P669

[7] Cecil Rhodes, His Private Life by his Private Secretary, P258-9

[8] James Rochfort Maguire with Charles Dunell Rudd and Francis Robert ‘Matabele’ Thompson negotiated and then signed the Rudd Concession with King Lobengula on 30 October 1888. See the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession? under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[9] Philip Jourdan was Rhodes’ last private secretary for the eight years before his death and published in 1911 the book Cecil Rhodes, his Private Life

[10] Sir Charles Metcalfe, the railway contractor. See the article The Beira and Mashonaland Railway – the Contractor’s stories under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[11] Albert Henry George Grey, a leading Imperialist and director of the British South Africa Company from 1898 and Administrator of Rhodesia from May 1896 to July 1897

[12] Gardener Williams was appointed manager of De Beers diamond mine at Kimberley in May 1887

[13] Sir Abraham Bailey was another of Rhodes’ close business associates and was to acquire extensive mining and land properties in Rhodesia and the Transvaal. In 1919 as a ‘Randlord’ he was appointed Baronet for his services to the British Empire.

[14] The Founder, P669-70

[15] Ibid

[16] Ibid

[17] Salsomaggiore has underground bromide-iodine water at depths of between 300 and 1200 metres that flow to the surface as springs

[18] Sir Lewis Loyd Michell businessman and general manager of Standard Bank, South Africa

[19] The Founder, P671

[20] Edward Dicey, journalist

[21] Gordon Le Sueur was author of the book: Cecil Rhodes, the Man and his Work, by one of his private and confidential secretaries (1913)

[22] The Founder, P671

[23] B.F. Hawksley was Rhodes’ solicitor

[24] The Founder, P671-62

[25] Cecil Rhodes, His Private Life by his Private Secretary, P244

[26] Ibid, P246

[27] Ibid, P265

[28] The Founder, P673

[29] Cecil Rhodes, His Private Life by his Private Secretary, P267

[30] Rhodes: A Life, P363

[31] Dr T.W. Smartt was a medical doctor and MP in the Cape Parliament. He was created KCMG and appointed a Privy Councillor in recognition of his public service

[32] Jack Grimmer had been Rhodes’ personal secretary and remained a close personal friend. Philip Jourdan writes in his book (P242) that he thought that of all the young men that served Rhodes he was most fond of ‘Jack’ Grimmer. On the morning of Rhodes’ last day, Grimmer said to him that he was looking much better and Rhodes replied, “No, my boy, this is my last day.” Rhodes left Grimmer £10,000 and Jourdain and Grimmer had been planning a trip around the world. But with their tickets booked Grimmer died shortly after Rhodes on 5 June 1902 aged 35 years from Blackwater fever, the result of numerous bouts of malaria in Southern Rhodesia

[33] Sir James Gordon McDonald wrote a biography entitled Rhodes, A Life. He handled Rhodes farming and mining interests in Southern Rhodesia as general manager of the Gold Fields Rhodesian Development Company and was a long-time close friend. He was knighted in 1929 and made KBE in 1937.

Jourdan: Cecil Rhodes, ‘Jack’ Grimmer and Tony at breakfast in the veld

[34] The Founder, P673-4

[35] Ibid

[36] Rhodes: A Life, P363

[37] Ibid, P364

[38] Cecil Rhodes, His Private Life by his Private Secretary, P267-8

[39] The Founder, P674

[40] Cecil Rhodes was born on 5 July 1853

[41] The Founder, P675

[42] Ibid, P675-6

[43] Ibid, P676

[44] Rhodes: A Life, P369