Forbes’ retreat down the Shangani river in December 1893

For background information on the incidents leading up to this event read the article James Dawson’s account of finding the remains of Allan Wilson under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

There has been considerable controversy around the fate of Allan Wilson’s patrol and much starts with its background. There is no doubt that the men that formed Forbes Column suffered greatly from inadequate protection from the poor weather, as they were equipped with capes, but had no tents. The rains were heavy in Matabeleland that December and the very wet conditions lowered their morale.

Not well-known is that Goold-Adams sent Captain Woon and a Cape Mounted Riflemen detachment from Emhlangeni to the Shangani river in December for news of Wilson and his patrol. The rains were so heavy however, even the horses became bogged down, and the attempt was abandoned. Goold-Adams himself planned to undertake a patrol to the Shangani from Emhlangeni on 25 January 1894, but this too was abandoned due to the weather.

In addition, there were disagreements between Raaff and Forbes and Wilson and Forbes. Many of those who had formed part of the Victoria Column believed that Allan Wilson should have been in command of the Column based on his experience fighting in prior African engagements. Even Raaff had much more African fighting experience than Forbes, who had never been in action in a native war,[1] and this gave rise to poor communication and some mistrust between the three individuals.

Museum Africa: Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele Captain Patrick William Forbes

The friction between them may have resulted in Wilson deliberately disobeying the order to return to the laager that same evening. There also appears to have been a mistaken belief by Forbes that Lobengula had been largely deserted by his regiments[2] and that his capture would be relatively easy. Comparatively little ammunition was taken by the Column and only two Maxim guns.[3]

As Robert Cary writes, “every single factor – economic, political, financial, human - pointed towards the need for haste. Never mind the lack of supplies, the shortage of food, the reluctance of many of the volunteer soldiers to go any further, the oncoming of the rains, the difficult bush country that lay ahead: the King had to be dealt with, and quickly.”[4]

The Column was under-provisioned from the start.[5] By 3 December when they reached the Shangani, they were living mostly on the meat from slaughter cattle, but in the retreat along the Shangani river all their slaughter cattle were driven off by the amaNdebele and they were forced to subsist on horse flesh.

The loss of Allan Wilson, Borrow and their patrol – a total of thirty-four men, resulted in a Court of Inquiry being held at Bulawayo in late December 1893. The fact that no report on their findings was ever issued has given rise to much speculation over the years.

3 December 1893

Major Forbes’s Column reached the Shangani river in the afternoon of 3 December. Within a mile of the river, they came across a herd of cattle guarded by some young amaNdebele men. When questioned by Colenbrander they revealed the King and his remaining followers had crossed the river only that morning.[6]

The King’s deserted scherm could be seen and wagon tracks along the riverbank. All the evidence pointed to the fact the King was just a short distance ahead. It was 3pm; Forbes called Major Wilson and told him to choose his best horses and follow the King’s tracks, with orders to return at sundown.[7] Major Walter Howard writes, “Let me hear tell you that with us, as with all ill-disciplined troops, there is always ill-feeling and jealousy. The Victoria men had always felt that Major Wilson should have been in command of all the troops who came in from the north and this feeling was noticeable on many occasions. There is little doubt that they now thought they would, so to speak, do Forbes ‘a shot in the eye’ by capturing Lobengula on their own.”[8]

However, instead of returning as they had been ordered to by 6.30pm, they stayed out but sent back Captain Napier with Scout Bain and Trooper Robertson. Napier’s message was that Forbes should cross the river by 4am next day and attack the King’s wagons.[9] Forbes sent Captain Borrow accompanied by twenty mounted men from B Troop as a reinforcement with a message that, as soon as it was light enough to move, he would come on in the morning.[10]

Major Allan Wilson Captain Henry Borrow

When Captain Borrow and his reinforcements had left to join Allan Wilson's patrol, Major Forbes reorganized his position[11] and waited for the expected Matabele attack, as they could see the amaNdebele cooking fires and hear their voices around them, but the attack did not come. All the native captives stated there were few men with the King, a few iNdunas (Mjaan, Manyao, Manondwane and Gambo) and some Bovane (Maholi slaves) and that the Regiments had orders to follow up the Column and stop it where they could. Forbes says, “I sent round again to warn the pickets to be on the alert…Few of us went to sleep that night as I was expecting an attack every moment.”[12]

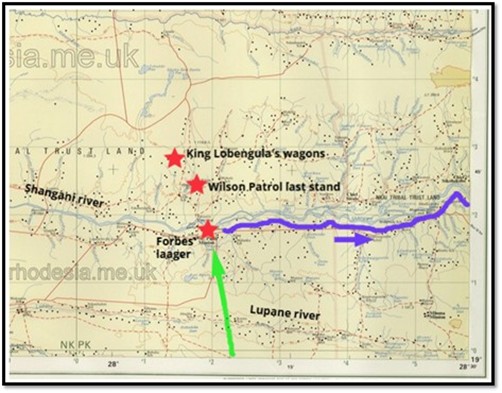

Map 1 – adapted from 1:250,000 map sheet SE-35-11 Kamativi; this map is used with consent from Window on Rhodesia with the site name: https://www.rhodesia.me.uk

During the night Sgt Judge and Cpl Ebbage returned, sent back by Wilson because their horses were knocked up. After questioning them, Forbes still believed Wilson might snatch the King and return and he would beat back the main amaNdebele force – it would still be a success.

Later still, just before midnight, Captain Napier, Scout Bain and Trooper Robertson rode in and were questioned by Forbes. Napier wrote in his diary, “I gave Forbes the message from Wilson…It was to the effect that Major Wilson was staying out all night close to the King and asking Major Forbes to go in with the Column and Maxim guns to be there at 4am next morning.”[13]

Later at the Court of Inquiry, Forbes stated it was out of the question to move in the darkness. “The Column, owing to the Maxims, could not move without making a considerable amount of noise, and it would be very dangerous to cross the river - deep sand and in the dark - when it was impossible to see what force might be waiting for us on the other bank where the bush was very thick”[14]

The amaNdebele are not asleep

At 1am on 4 December, Captain Borrow and twenty men of B Troop, plus Scout Ingram rode quickly out of camp to join Wilson, and despite the rain, Mjaan had taken part of his force silently across the river to guard the King’s camp against any attack. Half of the remainder, numbering hundreds, were told to cross the river and set up an ambush at the drift on the north bank.

4 December

Reveille was at 3am, the men wet and dispirited[15] after another uncomfortable night and when daylight came, Forbes prepared to move down the river and cross the Shangani to help Wilson. After going about half a mile, terrific firing was heard from the northern side of the Shangani. Colenbrander called out to Forbes, “They cannot keep that up for long, sir, with their stock of ammunition.”

Almost immediately afterwards, the Column came under fire from the bush some three hundred yards to their left which the Maxim’s returned. They were pinned down for more than an hour before the enemy fire slackened.[16] “Outnumbered by thirty to one and with less than 100 rounds of ammunition per man our position was very precarious but no ammunition was wasted for a man did not fire until he was pretty certain of his mark.”[17] Raaff wanted the Column to retire immediately from this open ground, but Forbes refused, saying that as soon as the Maxims were inspanned the amaNdebele would charge. Then Troopers Landsberg and Nesbitt rode into the square, but they had no news having become separated from Wilson’s party and deciding to return.

The Shangani river was now in flood[18] and at 7.30am the Column retired slowly until they reached the shelter of a strip of bush six hundred yards back, where they were able to dig in while Dr Hogg, the medical officer, attended to the men of the BBP who had been wounded.[19] At intervals during the fighting, they had heard the sounds of battle on the other side of the river, but realized that the rising Shangani made it impossible for them to go to the rescue.[20]

The firing on the other side of the river gradually died down, then seemed to renew further away. From this, many assumed Wilson had beaten back his attackers and then retreated north.The Column retired to their position of the previous night and were joined by Scouts Burnham and Ingram and Trooper Gooding sent back by Wilson to hurry Forbes on.[21] “Before dark rifle pits were dug around our bivouac, the horses being tethered in the centre with the wounded men inside the horse lines.”[22]

No movement was made this day as they thought they might be re-joined by Wilson's party. Forbes believed any survivors of Wilson’s party might travel up the north bank of the Shangani until the floods subsided and then cross to safety. Shortly after dark a terrific storm burst over them and the force spent a miserable night sheltering under their rain capes. During the height of the storm their slaughter oxen, on which they depended for their main food supply, became terrified by the thunder, and stampeded into the bush.

5 December

Forbes’ retreat up the Shangani began this day and they covered about fourteen miles.[23] One advantage was that the river gave permanent protection to the left flank. The Matabele did not impede its going,[24] but their main enemy now was the threat of real hunger. Their rations were almost exhausted and the loss of their slaughter oxen meant that they had no reserve. Ammunition was short and many of the men were suffering from malaria. Their clothes were in rags and their boots, constantly wet, falling to pieces. Their horses were weakened by lack of adequate grazing were almost useless for work. The men had to manhandle the Maxim’s across difficult stretches.

When darkness fell, Scout Pearl Ingram and Trooper Billy Lynch were sent with a verbal message from Forbes to Captain Dallamore at Inyati to move all the oxen and reserve ammunition to the main drift[25] on the Shangani river and informing Dr Jameson at Bulawayo of the situation.[26]

6 December

About another fourteen miles were done this day. Raaff’s men had the few fittest horses and took charge of the advance, rear and flanking parties. They laagered in a bend of the river and had a quiet night. One of the two remaining pack-oxen was killed for food.

7 December

Some calves were captured, a water-buck cow shot, and a good number of barbel speared in a pond. The Column was kept away from the river by thick bush but laagered on the river bank that night having managed just eight miles.

8 December

Some amaNdebele regimental slaughter cattle are captured. They had just finished a midday rest when the amaNdebele shadowing the Column up the river noticed the pickets were not keeping watch and made a surprise attack and nearly succeeded in driving away the horses. Raaff led a counterattack into the thick bush, but the amaNdebele had withdrawn, unfortunately taking all the cattle and the remaining pack-ox with them, the Column left with no meat. Heavy storms and the attack meant only about six miles were covered this day during which the Gweru river was seen to join the Shangani.

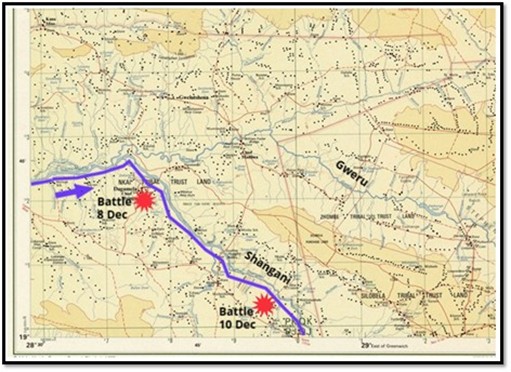

Map 2 – adapted from 1:250,000 map sheet SE-35-12 Que Que; this map is used with consent from Window on Rhodesia with the site name: https://www.rhodesia.me.uk

9 December

Forbes’ men were now struggling; the continued wet weather, a diet of horseflesh[27] and the constant strain were telling on all. Marching started at 5.30am. The horses were also weak and could do little more than walk. The Maxim’s on their galloping carriages were manhandled laboriously over a high ridge with drag ropes. On the other side was a scherm, they were Hlangabesa’ S people; he had been killed by Lobengula, and they were not loyal to him, and supplied the Column with sheep and four cattle.

The Column marched at 2pm but only managed three miles in thick bush and broken country. A quiet night, although very wet, and the oxen escaped.

10 December

The Column dried out their clothing after the very wet night, before marching at 8am. They made three miles through thick bush and broken granite kopjes. In the afternoon, they were resting in some kopjes divided by a deep spruit in which the horses were grazing. Eight of the horses were either shot or assegai’d before a Trooper signalled the alarm and the amaNdebele were spotted attacking again. At once fighting began, the amaNdebele were hard to spot in the long grass and the troopers took pot shots at the puffs of smoke. After about an hour of firing the amaNdebele withdrew. Sgt Gibson of the BBP was shot dead near a Maxim. It had been a close call.

Two miles further on, as the Column continued along the river bank and during a downpour of rain, the men were manhandling the Maxim’s on their galloping carriages and halfway down a steep bank at midday, when the amaNdebele in rocks on their right flank opened fire. The guns were dragged back whilst the rest of the Column returned the fire, but a heavy thunderstorm put an end to the fighting. Night was coming on and a laager was formed; the amaNdebele could be heard in the bush making their own shelters and shouting they would finish off the Column in the morning.

But about 10pm, the laager was vacated, with the Maxim galloping carriages abandoned, and twenty of the sickest and weakest horses left in their lines.[28] About sixty horses were taken on. Each man could take either his cavalry cape or blanket, the clothing left behind was made into dummies to trick the amaNdebele the laager was still occupied.[29] All accompanying dogs had to be killed.

The men left in single file led by Forbes and Burnham, no smoking allowed, six men carried each Maxim in a blanket, the cartridge belts loaded for quick action.[30] The few prisoners carried the reserve ammunition and were told a single sound would result in their being bayonetted; a guard being detailed for each. No sound was made and the Column moved out of the kopjes with regular halts to ensure they kept together in the dark. The men were so exhausted they often fell asleep at these halts.[31]

The amaNdebele attacked the empty laager at dawn and when their fire was not returned, they thought it was a trick before some more adventurous went forward and discovered the Column had gone. Raaff's ruse was effective; a good deal of ammunition and several hours were wasted by the amaNdebele. It had been a sound plan, the path ahead lay through thick forest, ravines, kopjes and jumbled boulders and was difficult to traverse.

The Column rested at midday having covered about twelve miles and then moved on and marched another six miles through open country until they stopped at 4pm where they rested until midnight.

11 December

By daylight they were in more open country and had travelled about twelve miles and the men’s spirits lifted. They started again at 4pm doing another six miles and rested until midnight.

12 December

The country became very broken, the bush dense; so, they waited until dawn and did a further five miles before halting. They reached the junction of the Vungu with the Shangani river. Grootboom and three ‘friendlies’ were sent on to see if there were wagons at the drift.

By now many of the men were bootless, their uniforms in shreds, they were struggling to carry the wounded and the ammunition and famished after existing on just two lbs of horseflesh per day with a seasoning of wild garlic roots.

In the afternoon they had marched for about a mile, when the amaNdebele opened fire from about two hundred yards. Sgt Pyke immediately returned fire with the Maxim sweeping the bush and allowing the horses, wounded and second Maxim to withdraw to the cover of the riverbank. Trooper Nesbitt (Salisbury Column) and Sgt Pyke (BBP) were both wounded on the Maxim before everyone found cover. Firing was hot for a while, then died away. They continued along the riverbank for two miles, some firing continued, before they laagered. This was the final encounter between the Column and the amaNdebele. The men were in the last stages of exhaustion from fatigue and the continuous rain, as well as hunger and the laager was very exposed.

Sgt Pyke on the Maxim giving covering fire, Trooper Nesbitt feeding the cartridge belt

13 December

A night march starting about midnight covered about ten miles by sunrise. Further thick bush and kopjes were negotiated with a halt at 9am to rest before resuming the march until midday. They started again at 2pm and to avoid a range of kopjes and likely ambush, the Column crossed the river, which was shallow here, and marched two miles on the eastern bank before re-crossing and laagering in an open space. There was some sniping from the amaNdebele, but it was ineffectual. They resumed again at 7.30pm in heavy rain, and marched until they reached a small tributary confluence where they rested until daylight. It was very cold and rained all night.

14 December

At dawn they marched on another two miles before recognising they had reached the Longwe river. As the country was more open on the eastern bank of the Shangani they crossed over to laager. At a small Maholi kraal, the head told them there were few amaNdebele about and he could guide them to Emhlangeni in twenty-four hours. He brought two cows that were both killed at once, one being eaten and the other cut up to be carried. Then two of the ‘friendlies’ turned up, saying there were no wagons at the drift and that Grootboom had gone on to Emhlangeni.

The kraal head then guided them for another five miles where they halted in an open valley for the night as Sgt Pyke could go no further. They had just stopped when two men were seen riding towards them, they were greeted with cheers and turned out to be Fred Selous and Charles Acutt. Carruthers writes, “Ultimately as we were resting during the heat of the day in comparative peace and feeling that at last, we had shaken off our pursuers, two white men suddenly appeared across the vlei at the edge of which we had halted. How the column cheered and yelled, for this meant that at length we were in touch with the longed-for relief. The two men were F.C. Selous and C. Acutt who had ridden out from their column to see if they could get any news of us, for we had been lost so long that the gravest fears were entertained for our safety. The relief column was barely three miles away, with them being, amongst others, Mr Rhodes and Dr Jameson.”[32] Their ordeal was over.

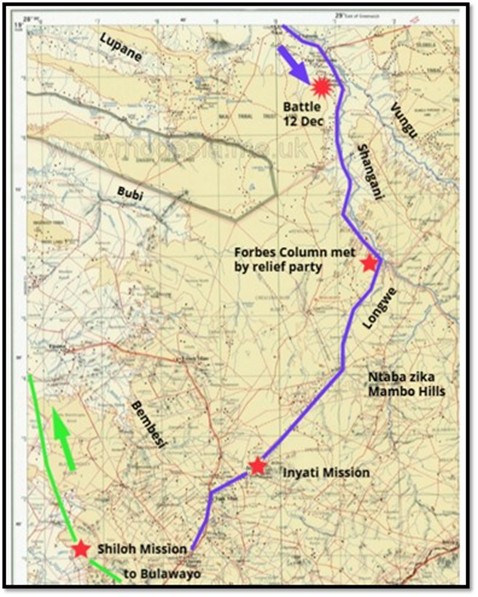

Map 3 – adapted from 1:250,000 map sheet SF-35-16 Gwelo; this map is used with consent from Window on Rhodesia with the site name: https://www.rhodesia.me.uk

The relief column on the Longwe tributary was reached after dark being guided by signal rockets. There the men feasted on bully beef, cookies, coffee with sugar. Trooper Bottomley wrote, “Never have I seen such a bowed-down, miserable crowd as these poor fellows.”[33]

Willie Posselt[34] wrote, “Selous brought Major Forbes - he was the first to arrive. Dr Jameson and Rhodes shook hands with him, but Rhodes walked away from Forbes and the Doctor spoke to Forbes for some time. I think no one knows what he said. Was he (Forbes) accused and blamed that Wilson's party lost their lives? But when Commandant Raaff and his men came, three hearty cheers went up for Raaff.”[35]

Alfred Drew wrote, “it was feared at first that, besides Allan Wilson's party, those left on the other side of the Shangani river, under Major Forbes, had also been annihilated, but after a few days during which we were preparing to go to their relief and getting some small reinforcements from Bulawayo, news was brought in to Inyati by the faithful Fingo native John Grootboom,[36] giving us the whereabouts of Forbes and his men. Rhodes, Jameson, Selous, Willoughby, Beale and other celebrities had meanwhile come out to Inyati. The Wilson disaster appeared to create a set back after our previous successes and it must have been one of those occasions when Rhodes felt he had to be right in the thick of things. Rhodes and his friends left with all the mounted men next morning and after going about twenty-five miles, Selous got in touch with the stricken force. It was a great reunion when they reached our camp that evening. They had lost all their horses; they had to consume several for food. We handed over our horses to them next morning and went back with them to Inyati on foot, doing the twenty-five miles in the one day, not a bad performance in the pouring rain along a track like a quagmire in places, and with practically no food…”[37]

16 December

The combined Column set off for Emhlangeni (Inyati Mission) Forbes’ men riding horses, their owners walking alongside for the twenty-five miles with Inyati Mission reached after dark.

17 December

Forbes’ men then travelled by ox-wagon to Bulawayo that was reached on the 18 December.

The Columns responsible for the occupation of Matabeleland are disbanded

21 December

Columns started off for Victoria and Salisbury with a month’s rations for the road. Those returning to Johannesburg left for Tati under Captain Carr the following day. The roads were in poor condition with the heavy rains; Victoria under Lieut Beale was reached on 18 January, Salisbury under Captain Spreckley was reached on 20 January. The Bechuanaland Border Police under Goold-Adams returned to their base at Macloutsie. Rhodes in a speech on the 19 December, thanked them for their good conduct and prompt service and for the support they had given to the British South Africa Company.

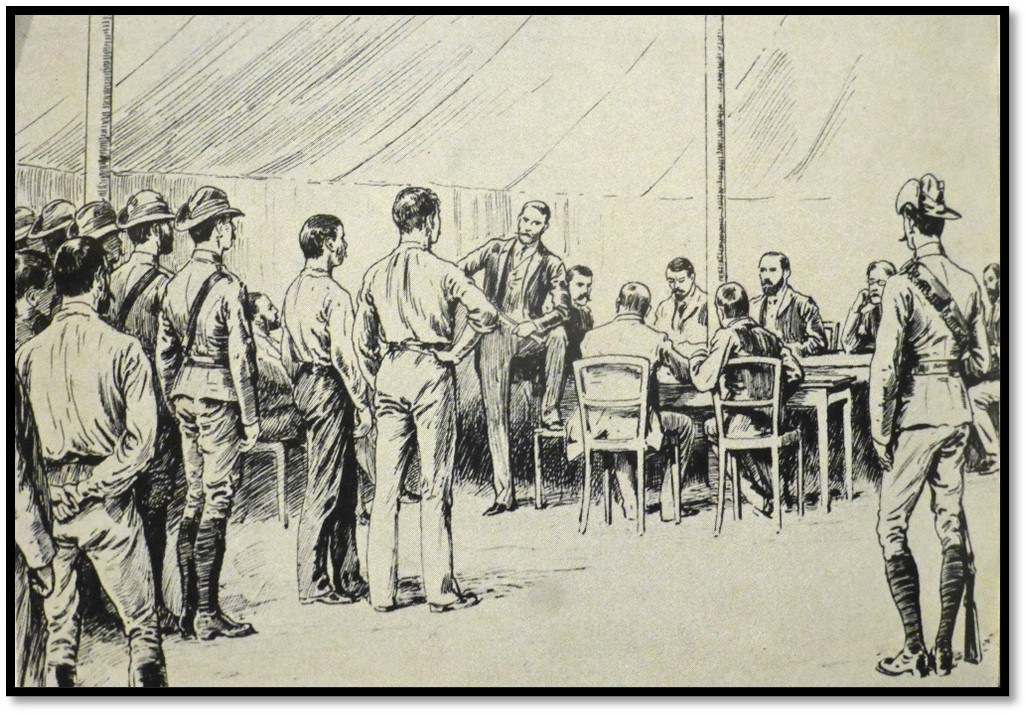

A Court of Inquiry

A Court of Inquiry[38] was convened on 20 December at Forbes’ request to examine the pursuit of Lobengula and the events of 3-4 December.[39] Goold-Adams told Loch that Jameson wanted the friends and relatives of those killed to know if anyone was to blame for their deaths.[40]

Most witnesses were critical of Forbes’ leadership. Raaff had called for the Allan Wilson patrol to be recalled back to camp on the 3 December, but had been disregarded as Forbes was prepared to send Borrow’s patrol as reinforcements. Forbes had been prepared to send a Maxim with Borrow, but Raaff had objected, whereupon Forbes had said, “I shall send the men, not the gun.”[41]

Their task was not made easier by the death of Raaff who fell ill with peritonitis almost immediately they reached Bulawayo and died on 26 December. Loch in his evidence to the Court felt Forbes should have laagered on the north bank of the Shangani and would then have been able to give Wilson support,[42] but he also felt the officers had not given Forbes sufficient support and Wilson should have obeyed orders to return to the laager the same evening, “whilst on one side the O.C. failed to command the confidence of his officers, many of the officers in their part failed in their loyalty to their O.C. which is essential for the maintenance of discipline.”[43]

The main criticism of Forbes was that he underestimated the amaNdebele. He had reduced his force, sending back 115 men, all the wagons, two Maxims and the Hotchkiss gun. The remaining men had 100 rounds each; the Maxim’s 2,100 rounds each.[44]

No report on the Court of Inquiry’s findings was ever issued – another source of controversy.

Dr L.S. Jameson Commandant P.J. Raaff

The amaNdebele surrender is incomplete

Jameson's priority was to secure the complete surrender of the amaNdebele and establish peaceful conditions by dismantling their military system and the disbandment of their impis. Messengers were sent around the kraals to announce that only those who surrendered their arms would be allowed to return to their villages and proceed with the cultivation of their crops.

The initial amaNdebele response was good, but after a few weeks, it seemed that as long as the fate of Lobengula was unknown[45] and the impis remained in the field, they wanted to retain their weapons. Jameson’s answer was to set up a civil police force of a hundred and fifty men under Lieut Bodle backed up by three hundred Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) who were posted for duty in Matabeleland.[46] Garrisons were established at Inyati and on the edge of the Matobo Hills.

Jameson's order that the amaNdebele could not cultivate their crops until they had surrendered their arms was heavily criticised by the British press. Lord Ripon. the Secretary of State for the Colonies, instructed the High Commissioner, Sir Henry Loch, to notify the Company that the surrender of arms was to be construed "in a very liberal spirit." Many of the amaNdebele therefore buried their rifles and ammunition and assegais – to be recovered in March 1896.

Following the Singuesi battle Gambo’s impi had divided in two.[47] Some under Masiwe entered the Matobo, the remainder under Gambo himself moved to the Gwaai river before Gambo himself joined Lobengula.

Major Browne took 65 mounted BBP Troopers and 30 dismounted of the British South Africa Company force with two Maxim’s to Usher’s Farm. The amaNdebele agreed surrender terms and laid down their arms. Captain Spreckley with 60 mounted men of the British South Africa Company force sought out Gambo, but failed, and Gambo only came in at the end of March 1894. Lieut Marsham with 50 BBP Troopers went to the Mangwe area seeking iNduna Gargo (Fargo) in the vicinity of the Shashani river, kraals were burnt, but no military action took place and there was no surrender.

Some amaNdebele came in and surrendered their weapons, but it was limited. Browne in a month collected just 101 guns and 1 300 assegais. Glass maintains the forces were more interested in cattle-rustling than in fighting.[48]

Reward for unpaid service – the Victoria Agreement

The volunteers of all three Columns – Victoria, Salisbury and Tuli - were to receive no pay, but were promised land and loot when the campaign was over. In August 1893, a "Loot" committee was formed in Victoria with instructions to draw up an agreement on the rewards. The final agreements were:

(1) Each volunteer would be entitled to a 3 000 morgen (6 351 acres) farm in any part of Matabeleland with a quitrent of ten shillings a year. The farms had to be marked out within four months and the Company reserved the right to purchase their farms at £3 per morgen with compensation for improvements

(2) Each volunteer was entitled to 15 gold quartz reef claims and 5 alluvial claims with the proviso that a 30-foot (9 metres) shaft be sunk within 6 months or a 60-foot (18 metres) shaft within 12 months

(3) Cattle were to be divided one-half to the British South Africa Company and the balance to men and officers in equal shares.

The final document was given to Jameson on 4 October, although there were several new clauses which he refused to sign, instead signing the original document of 18 August 1893.

After the invasion, Rhodes proposed that all members of the BBP who had taken part also be accepted, but High Commissioner Loch told Lieut-Colonel Goold Adams it could not be accepted.

Carruthers adds that soon after the occupation of Matabeleland, “Farm rights were being sold for ten pounds each and loot rights were fetching twelve pounds. The Loot committee eventually accounted for three hundred and sixty-two thousand head of cattle and paid out forty-two pounds on a right.”[49]

The ignominy of Troopers Daniel and Wilson

With active campaigning at an end, the amaNdebele drifted back to their kraals. They reported that before Forbes's Column reached the Shangani, Lobengula had decided, in a last effort to halt the pursuit, they might stop for money. He had accordingly sent two messengers, Betchane and Sehuluhulu, with one thousand sovereigns and orders to intercept the Column. They were to say that the King admitted he had been conquered, and that the white men were to take the money and turn back. “Here, white men, take this and go back. I am conquered.” The messengers met the Column the day before it reached the Shangani (i.e. 2 December 1893) and hid in the bush until it went by and then followed and gave the money to two men in the rear guard. They kept the incident secret and it only became known when local natives informed William Fulmer Usher who reported what he had been told to Dr Jameson who responded quickly.

Suspicion fell on BBP Troopers William Charles Daniel and James Wilson, both officers' batmen, who had not been members of the rear guard that day but had dropped to the rear of the Column. Soon after the Column's return they had been seen to be in possession of large amounts of gold. Daniel explained that he had won the money at cards and Wilson said he had brought the money with him. They had both bought farm rights and had paid for them in cash. A point in favour of the two men was a statement by Sehuloholu that the man to whom he had given the money could speak his language well and neither Daniels nor Wilson knew isiNdebele.

Indignation over their reported actions ran high with the public believing that had the receipt of the money and Lobengula's message been reported, Forbes might have been induced to turn back on reaching the Shangani river and the tragedy of the Wilson Patrol would have been avoided. The circumstantial evidence against Daniel and Wilson was strong. They were tried by the Resident Magistrate[50] and four assessors at Bulawayo[51] on 28 May 1894, found guilty and sentenced to fourteen years' imprisonment with hard labour.

The Bulawayo trial of BBP Troopers Daniel and Wilson

But the High Commissioner's legal experts pointed out that the Magistrate's powers did not entitle him to pass sentences of more than three months' imprisonment. They also considered that the conviction was against the weight of evidence. The sentences were afterwards quashed and the men released after serving two years. The identity of the isiNdebele speaker alleged to have received the money was never established, nor, beyond the Matabele statements, was it ever proved that there had been a box of sovereigns, which, of course, could have been part of the payments for the Rudd Concession. It is inconceivable that the Matabele would have invented the story, and Lobengula's unflattering view that the white men might stop for money rings true. The whole incident remains a dark blot on the pages of Rhodesia's story.[52]

Allan Wilson’s colleagues paid tribute to his character

Many writers have questioned why so many officers were permitted to accompany Wilson across the Shangani river. Major Forbes allowed him to pick his own men, and it was only natural that the officers of the Victoria Column - many of them his own personal friends, men he had known in civilian life – wanted to help him to capture Lobengula.

Walter Howard wrote, “Major Allan Wilson was one of the most gifted leaders of men I have met. Personally brave to rashness, yet extremely careful and considerate of the men under his command, it followed that the men would go anywhere with him. It is to this hero worship of Wilson, so well deserved, that I attribute the large number of officers who accompanied him on that last fatal reconnaissance.”[53]

Jack Carruthers said, “My last words with Wilson were under the eaves of the Inyati Mission where he was sheltering from the rain with a plaid shawl over his head and shoulders…I told Major Wilson I would go to Bulawayo with the loot cattle and would return to join him at Shiloh. As I wished him goodbye, Wilson rode away on his big cream horse in his shirtsleeves, riding trousers and top boots. In his belt was a tobacco bag with his clasp knife on the side hook. His waterproof coat hung loosely over the pommel of his saddle and he carried no weapon. An easy-going man, never perturbed, a leader of men, whom to know was to like.”[54]

References

R. Cary. A Time to Die. Howard Timmins, Cape Town 1969

D. Clark. John Sampson’s letter of 20 December 1893

S. Glass. The Matabele War. Longmans Green & Co Ltd, London 1968

Major Walter Howard in Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir printed for the celebrations held in Bulawayo between Monday 30 October to Sunday 5 November 1933

N. Jones. Rhodesian Genesis. Rhodesia Pioneers’ and Early Settlers’ Society. Bulawayo, 1953 (most of the references were made in an account by Jack Carruthers)

W.A. Wills and L.T. Collingridge. The Downfall of Lobengula. Books of Rhodesia, Vol 17, Bulawayo 1971

Appendix

John Sampson’s letter

The contemporary letter to Sampson’s brother provides a very interesting account of the Occupation of Matabeleland from the start and the subsequent effort to capture Lobengula and Forbes’s retreat up the Shangani river. John Sampson was a lieutenant in No. 2 Troop under Captain Segar in the Victoria Column led by Allan Wilson and he played an active part throughout the campaign.

Bulawayo, 20th December 1893.

I wrote you a letter a good while ago but I have been away from here on patrol for 33 days, and so the letter was not posted, and has now been lost. We left Victoria on Oct. 5th, and came steadily on up to the 16th, when our scouts had a small skirmish with the Matabele, taking some 250 cattle. On the 18th we joined the Salisbury column, bringing our total strength up to 700 of all ranks. From here we had continual skirmishes between our advance guards and flanking parties, and the Matabele. On the 25th we crossed the Shangani River and got into Matabeleland proper. At four a.m. we were attacked by about 5 000, and a very warm time we had for the next two hours, bullets of all shapes and sizes simply hailing round us. About six we had driven them off a bit, and two troops of mounted men went out and drove them out of the bush. We came off very lightly, only one man killed and six wounded. We started on our march again in the afternoon, and had no more fighting for two days, and then only skirmishes. On the Ist November we turned a good deal out of our way to avoid some very thick bush and laagered up our wagons in the usual way at about ten o'clock. I was in command of the left flanking party, and did not get in until 11 pm. Just after breakfast the alarm went. The enemy had crept up through some bush to our right rear, and killed one of our Vedettes, but not until they had given the alarm. The men guarding the horses started bringing them in, but the bullets, and the noise of the Maxims scared them, and they stampeded straight for the Matabele. Some of us galloped out at once to turn them but could not; and we should have undoubtedly lost 400 or 500 of them if the enemy had not started firing on us and on them, which made them turn sharp off to the left. We then managed to get them under control, and brought them back, bar two or three shot. In the meantime, the fight had been going gaily on, but chiefly round the Salisbury side: all the country on our side being open, the Matabele did not fancy coming round there in the face of three machine guns, and 300 rifles. The fight lasted about an hour and a half and the enemy's loss must have been very heavy. We cannot tell exactly, because they carry off as many of their dead and wounded as they can. Our loss was, I think, three killed, and eight wounded. We had no more fighting worth speaking of after this and arrived at Bulawayo (which was burnt down) on the evening of the 4th of November. The King had fled north ten days before, with a lot of people and cattle. Our loss up to this had been very small, only ten men killed and died of fever, and about twenty wounded. The Company were most anxious to get hold of LoBengula; so, on the 14th 300 mounted men, with three Maxims and a seven-pounder, started in pursuit. Before this we had been joined by Col. Gould-Adams, with the Bechuanaland Border Police, and Commandant Raff’s column from Tuli. They had only had one small fight on the way. We went as far as a Mission Station 45 miles away and left half our men there, and with the rest went on another 25 miles, but found the King had gone more to the west. We were only supposed to be away three days and were carrying rations accordingly. We returned to the Mission Station (Inyati), and the next day started for a trading station (Shiloh) 27 miles S.E. and met there some of our infantry and waggons of rations. After one day we started again with five of the waggons, and infantry, and followed the King's waggon track. We had been having rain now for four days, and the road was awful. We could only get our waggons about seven or eight miles a day, so after three days we sent them back to Inyati, and went on with 130 men, ten days' rations on pack horses, and two Maxims. This was about as risky a patrol as ever started. We travelled for five days through thick bush country, until December the 3rd. On the evening of that day, we got to the place where the King stayed the night before. I was acting adjutant, and with Bowen, the A.D.C. to my chief, Major Wilson, was riding in front of the hollow square, when suddenly Major Wilson ordered us into the square, and started away with 20 men to follow up, and simply find out (as we thought) how far the King was on a-head, and what force he had with him. He took all our best-mounted men and so had no less than six of our officers with him. We halted and formed up in a square for the night, expecting him and his party back every minute. Soon after dark we found we were surrounded, and quite expected an attack, but it did not come; neither did Major Wilson and our men. Later a messenger came back from them, saying that they had dashed right through the Matabele, up to the kraal in which they thought the King's waggons were, but it was so dark they could not see them, and had to retire, and wanted more men and a Maxim. Major Forbes, the CO, sent out Capt. Borrow and 18 Salisbury men to help them and reinforce them until we could move in the morning. We moved at daybreak, and as we moved heard heavy firing in the direction of the King. A few minutes after we were ourselves attacked. We were moving along the bank of the Shangani, and on our left, about 180 yards away, was a belt of bush, simply alive with enemies. We had to halt and stand in the open and fight it out. For three hours we stood there, and it only shows how badly they shoot, we lost only two men wounded, and ten horses shot. A messenger came from Wilson for help in the middle of the fight, but we had all we could do to hold our own and could not move. After a time, we were able to retire to a better position, and there we stayed for the night, fortifying ourselves as well as possible. We had a frightful night. It rained, thundered, and hailed, and we had thousands of Matabele round us, who we thought would attack us every minute. Wilson and his party we have heard nothing of, and very much fear he and all his men are gone, 32 of them. Sixteen of them belonged to Victoria—all good and well-known men. We felt it dreadfully; it was such a sweep of what were in this country, old friends, and men with whom we had lived, not only in this campaign, but ever since we have been in Mashonaland. We sent off two men to Bulawayo for reinforcements and rations. We had to retire, as our rations were nearly out, ammunition only 50 rounds a man and four wounded to get along. All went well for the first four days. On the 8th of December we took some cattle, and that promptly brought on an attack. We beat them off, losing more horses killed and wounded, but no men. All our horses were knocking up; we had no corn for them. On the 10th we had to fight again in an awful place. At one time I thought we had a poor chance of ever getting away. But the Matabele are not as brave as supposed and were afraid to charge us. They will not face the Maxims. Well, we got out losing one man, and several more horses, and fortified ourselves for the night in the best position we could, and that was bad. Our gun horses were done up so we decided to leave our gun carriages and make a forced night march, and so try to escape our enemies, who had gone for more men. We got away without being attacked, but that was, I think, the most anxious day and night I have ever spent. We marched some 15 miles that night and started again at one for another march. Every day we were leaving horses behind, men were bare-footed, and all rations gone, and for four days we had to live on horseflesh. On the 12th we were again fighting for our lives. We had some more men wounded and horses killed. On the 14th we managed to get hold of some bullocks, and had a tremendous feed of beef, and it was good. The same day all our luck came back. We met a relief party and were once more safe. We had a most hearty welcome. Men one had never seen seized one's hand and nearly wrung it off. It was a bit too much for most of us. We had been away altogether 30 days, with 11 days' rations, and had 20 days wet through. My great coat was rotten, and my belt in the last hole. That night was the first night I had slept out of my boots since we left Bulawayo. We stayed one day at Inyati, and then came here, arriving on the 18th nearly tired out. We lost one man (besides Wilson's 32) and seven wounded and numerous horses, but many of the latter from overwork and poverty. We had wonderful escapes. My horse was shot on the 4th, and I had many close shaves from bullets. The force is now being disbanded, and a permanent force raised. I think this has been one of the hardest patrols ever undertaken, and it is perfectly wonderful how we got through. We were 130 miles from our base and had no communication from November 29th till December 14th. l am fit, and safe, and well, and have not got a scratch. This is a most sketchy account, but I am not good at descriptions, and that patrol of 400 miles is not nice either to write or think about. We none of us look back with joy to four days' living on horseflesh of the poorest and hardest kind.

John Sampson

Permission to reprint the letter was given by his great, great, great nephew David Clark.

The Victoria Column

John Sampson was a Lieutenant in No. 2 Troop, under Captain Segar and William Bastard in the Victoria Column. Their Troopers total 30 married men. In total the column had 414 Martini-Henry armed men, 400 Shona warriors, 22 ox-wagons, three Maxim’s, a one-pounder Hotchkiss, and a seven-pounder gun, also carrying its own munitions and supplies. The ammunition consisted of 180,000 rounds of Martini-Henry cartridges, 1000 Hotchkiss rounds, 300 seven-pounder rounds, and an unknown number of Maxim and revolver rounds. This column also had 250 bayonets for Martini-Henry riffles.

Each man was promised clothing, weapons and ammunition, and horses. In addition, each was promised a farm and mineral rights in Matabeleland as a reward for his services

David Clark at: d.clark1948@yahoo.com

Notes

[1] A Time to Die, P40

[2] Some Regiments had returned to their kraals, but captured amaNdebele accounts agreed the King had about 3 000 men with him, mostly from the Insukamini, Ihlati and Siseba Regiments with a few from the other Regiments (Forbes, The Downfall of Lobengula, P158)

[3] The fearsome Maxim, the equivalent of a hundred rifles being fired by one man, were termed “Sigwagwa’ s” by the amaNdebele

[4] A Time to Die, P13. Some time later, a slave boy found at the King’s scherm said this was a lie. All the remaining amaNdebele were not with the King who had ordered an impi of 2 500 to go back and attack the Column whilst it was still in the bush

[5] Tyndale-Biscoe wrote in his diary, “We are now living on anything we can pick up, mostly meat and kaffir corn…there is a great deal of discontent among the men on account of the rations” (A Time to Die, P42)

[6] A Time to Die, P51

[7] Forbes writes, “The column was marching slowly on, and I rode back to it. I called Major Wilson out at once and told him that I wanted him to take his twelve best horses and push on along the spoor as fast as he could to see which way it went, returning by dark, this was about five o’clock and there was about one-and-a-half hours more daylight... Major Wilson at once called out his twelve best mounted men, and several other officers including Captains Kirton and Greenfield, asked if they might go, and were allowed; they all understood that they were to be back that night…”(The Downfall of Lobengula, P157)

[8] Rhodesian Genesis, P96

[9] Forbes was told that Lobengula started with four wagons, but that the oxen were knocked up and being pulled by his warriors. The Downfall of Lobengula, P138

[10] Ibid, P96

[11] Major Walter Howard writes, “we had nothing in the shape of a laager at our bivouac just a man’s saddle facing outwards and behind it the man” African Genesis, P96

[12] The Downfall of Lobengula, P160

[13] A Time to Die. P73

[14] Ibid, P74

[15] Many of the men were now infected by the defeatism of Raaff, Lendy and Francis (A Time to Die, P97)

[16] The Maxim guns needed inspanning to move them which meant that they would be out of action

[17] Rhodesian Genesis, P97

[18] The Shangani had been easily fordable at 1am when Borrow rode across; now at 7.30am it was a raging torrent

[19] Corporal Williams, Troopers Middleton, Shanaghan, Newton and Captain Napier and Le Fleur (a mule driver) Sixteen horses had also been killed and two mules in the skirmish

[20] Major Walter Howard Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir

[21] Burnham’s first words being, “I think I may say, Major, that we are the only survivors from Major Wilson's party.” (A Time to Die, P100)

[22] Rhodesian Genesis, P98

[23] The Matabele War, P229

[24] It is fortunate that the amaNdebele impi’s on the southern riverbank were in no real mood for fighting and mostly just harassed the retreating Column

[25] This refers to the Hunter’s Road drift between Inyati Mission and the Fort Ingwenya site. The drift about 15 kilometres north of the Ntaba Zika Mambo hills and between the Longwe and Nsangu tributaries of the Shangani river

[26] Forbes writes that the strain on his nerves so affected him that Ingram completely forgot what he was supposed to tell Dr Jameson (The Downfall of Lobengula, P171)

[27] Captain Finch wrote, “the skin of my horse, which I killed for food, made one pair of shoes, the holsters another pair, and the flaps of the saddle the third.” (A Time to Die, P125)

[28] Captain Tancred and a patrol of sixteen men recovered the galloping carriages in April 1894

[29] Rhodesian Genesis, P100

[30] The Maxim’s were carried in blankets and once they were clear of the amaNdebele lines the two Maxim’s were balanced across the saddle of a horse with a Trooper holding it on either side

[31] Major Walter Howard Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir

[32] Rhodesian Genesis, P102

[33] A Time to Die, P138

[34] Willie Posselt was one of those who rode from the old Mission Station at Emhlangeni (Inyati) the twenty-five miles and met Forbes patrol in the late afternoon

[35] Rhodesian Genesis, P102

[36] John Grootboom – there are numerous references to Grootboom on this website www.zimfieldguide.com. A word search will refer to the various events where he gave invaluable service in the 1890’s.

[37] Rhodesian Genesis, P103-4

[38] The Court of Inquiry President was Goold-Adams plus Sir John Willoughby and H.M. Heymans as members

[39] Forbes wrote a statement of twenty thousand words justifying his actions

[40] The Matabele War, P230

[41] The Matabele War, P231

[42] Forbes writes, “The day before we got here Major Wilson and I had discussed the question and agreed that it was not advisable to take the Column any further than the Shangani… we could scarcely get through before we had run out of food and I wish to avoid this if possible.” (The Downfall of Lobengula, P158)

[43] A Time to Die, P141)

[44] The Matabele War, P232

[45] James Dawson’s report reached Emhlangeni on 1 March 1894. He confirmed that Lobengula had died of smallpox, or fever on 22 or 23 January 1894 approximately miles south of the Zambesi river

[46] The BBP had been reduced to fifty by the end of March 1894 and Goold-Adams and all his force left Matabeleland on 8 May

[47] See the article The Southern Column’s skirmish at the Singuesi river on 2 November 1893 revisited under Matabeleland South Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[48] The Matabele War, P236

[49] Rhodesian Genesis, P113

[50] The Resident Magistrate was Herman Melville Heyman

[51] The four assessors were Lord Henry Paulet, James Dawson, C.P. Clerk and F.J. Newton

[52] But does not end here. Read that Dawson admitted to keeping one thousand sovereigns given to him by Mjaan in the article James Dawson’s account of finding the remains of Allan Wilson under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[53] Major Walter Howard Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir

[54] Rhodesian Genesis P93-4