Two of Lobengula’s Relics

The fortieth anniversary of the occupation of Matabeleland was commemorated by an official programme of Events that were spread over the week of Monday 30 October to Sunday 5 November 1933 and the publication of the Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir and another publication, Matabeleland 1893 – 1933 An Illustrated Record of the Fortieth Anniversary Celebrations of the Occupation. The first has a short article on two relics that once belonged to Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele. According to the article both these items are today kept by the South African Museum at Cape Town.

The gold neck chain with a five pound gold sovereign

The article on this website Why Lobengula sent envoys to Queen Victoria in the late nineteenth century[1] explains the rivalry between the two major rival concession-seekers at Umvutcha; the British South Africa Company (BSAC) headed by Cecil Rhodes and the other represented by the Bechuanaland Exploration Company which had two of Victoria’s sons-in-law as directors and was Lobengula’s preferred choice…both company’s claimed to have the backing of the British Government.

On 30 October 1888 after much persuasion Lobengula signed the Rudd Concession which was co-signed by Rudd, Maguire and Thompson on behalf of the BSAC and witnessed by Reverend Helm and Dreyer. Unfortunately for Lobengula, Maund and his fellow directors in the Bechuanaland Exploration Company were persuaded by Rhodes to amalgamate their common economic interests and with colonial office backing the BSAC received the royal charter in 1889 on the back of the Rudd Concession and the financial strength of Rhodes’ personal wealth.

Matabeleland is in an uproar after the Rudd Concession is signed

This resulted in the subsequent furore from the amaNdebele who believed that the country had been sold and many believed that the King was complicit. According to Edward Arthur Maund, who was the local representative of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company and also the correspondent for The Times, he asked for a gold mining concession in Mashonaland from Lobengula who was receptive to the idea of the English keeping the Portuguese at bay in the East and replied: “But Maundy, I want you to do something for me first. They tell me that the white queen no longer exists and that is why the white men come up here and bother me. I want you to take two of my men home to see whether the white queen is living.” After some thought Maund said he agreed to the King’s request as there was no imperial government representative in the country, John Moffat being elsewhere.

Next day Lobengula dictated a letter to the Queen which Maund wrote down and which was sent to Rev Charles Helm at Hope Fountain Mission because he was trusted by Lobengula. Helm deleted a clause requesting a protectorate and changed it to a request to the Queen for help against Lobengula’s enemies. The text of the letter was: “Lobengula desires to know that there is a queen. Some of the people who come into this land and tell him that there is a queen, some of them tell him there is not. Lobengula can only find out the truth by sending eyes to see whether there is a queen. The Indunas are his eyes. Lobengula desires, if there is a queen, to ask her to advise and help him, as he is much troubled by white men who come into his country and ask to dig gold. There is no one with him whom he can trust and he asks that the queen send someone from herself.”

Maund takes two amaNdebele indunas to see Queen Victoria

Mshete (aged 60 years) and Babayane (aged 75 years) were to accompany Maund and Johan Colenbrander (the translator) as Lobengula’s envoys: “These are the men who are to be my eyes, ears and mouth.” Lobengula provided some cattle for the road and agreed to pay all expenses amounting to about £600. Maund says: “His majesty thereupon got into his wagon and took down a handkerchief full of English sovereigns, some of which had been obtained by the Rudd Concession. He then counted out a sum for the expenses of his embassy, though it was not quite sufficient.”

They left Gubulawayo in late November 1888. Maund bought clothes for the envoys at Tati and Shoshong and suits at Pretoria. At Kimberley they boarded the train and were terrified when it moved at speed. Maund turned to Babayane and said, “What a King’s soldier and afraid?” and to show he was not afraid Babayane put his head out the carriage window for half an hour!

Queen Victoria receives the Envoys and they are given a letter for Lobengula and gifts

On 2 March, 1889, they were received at an audience with Queen Victoria at Windsor. A last interview followed with Lord Knutsford after which a great crowd of well-wishers saw them off on their journey home. The following was the full reply of Her Majesty to Lobengula through Lord Knutsford;

“I, Lord Knutsford, one of Her Majesty's principal Secretaries of State, am commanded by the Queen to give the following reply to the message delivered by Mshete and Babayane. The Queen has heard the words of Lobengula. She was glad to receive these messengers and to learn the message which they have brought. They say that Lobengula is much troubled by the white men who came into his country and ask to dig for gold and that he begs for advice and help. Lobengula is the ruler of his country and the Queen does not interfere in the government of that country, but as Lobengula desires her advice, Her Majesty is ready to give it, and having therefore consulted her principle Secretary of State holding the seals of the colonial department now replies as follows;

In the first place the Queen wishes Lobengula to understand distinctly that Englishman who have gone out to Matabeleland to ask leave to dig for stones have not gone with the Queen's authority and he should not believe any statements made by them or any of them to that effect. The Queen advises Lobengula not to grant hastily concessions of land, or leave to dig, but to consider all applications very carefully. It is not wise to put too much power into the hands of the men who come first and to exclude other deserving men. A King gives a stranger an ox, not his whole herd of cattle, otherwise what would other strangers arriving have to eat?

Mshete and Babayane say that Lobengula asks that the Queen send him someone from herself. To this request the Queen is advised that Her Majesty may be pleased to accede. But they cannot say whether Lobengula wishes to have an Imperial officer to reside with him permanently, or only to have an officer sent out on a temporary mission, nor do Mshete or Babayane state what provision Lobengula would be prepared to make for the expenses and maintenance of such an officer. Upon this and any other matters Lobengula should write and should send letters to the High Commissioner at the Cape, who will send them direct to the Queen. The High Commissioner is the Queen's officer and she places full trust in him and Lobengula should also trust him. Those who advise Lobengula otherwise do deceive him.

The Queen sends Lobengula a picture of herself to remind him of this message and that he may be assured that the Queen wishes him peace and order in his country. The Queen thanks Lobengula for his kindness which, following the example of his father, he has shown to many Englishman visiting and living in Matabeleland. This message has been interpreted to Mshete and Babayane in my presence and I have signed it in their presence and affixed the seal of the colonial office.

(Signed) KNUTSFORD

Colonial Office 26 March 1889”

The Queen’s gifts

Queen Victoria presented Mshete and Babayane with gifts of snuff boxes and they were taken on a tour of London’s attractions including the Alhambra musical variety theatre, museums and art galleries, Madame Tussaud’s waxworks and the London Zoo and the gold vaults of the Bank of England.

Lobengula’s gift consisted of an 1887 Jubilee five pound gold sovereign hung on a chain with massive links which was inscribed; “From Queen Victoria to Lo Bengula. March 1889.”

This chain looked loke gold but was not. It was Pinchbeck, a form of brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) so that it closely resembles gold in appearance and was contained in a red leather case.

Queen Victoria’s gift to King Lobengula

Only in August 1889 did Mshete and Babayane, with their conductor E. A. Maund and interpreter Johan Colenbrander, reach Bulawayo and report to Lobengula. They delivered the letter from Lord Knutsford, then Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Queen Victoria’s gift is a diplomatic faux pas

Lobengula acknowledged the letter but said nothing about the necklace. However there are contemporary reports saying that Lobengula disliked and mistrusted the gift. The King was very suspicious of the red case the gift came in; red was believed unlucky by the amaNdebele and disliked by them. The story goes that when he opened the lid, he became angry and threw the chain and gold sovereign away. Also that it stayed on a pile of rubbish all day but under the cover of darkness one of the King's wives crept out and took it.

Queen Victoria’s gift was seen by Lobengula as part of a deception played upon him. He realised after putting his mark on the Rudd Concession that he had been misled and sought to have it invalidated. When Queen Victoria approved the Rudd Concession and granted the BSAC a Royal Charter he believed she had been influenced by Cecil Rhodes and that he had been made to look like a fool in the eyes of his people.

Mr D. Niven the Librarian at the Bulawayo Public Library who supplied the photos stated in the article that Lobengula, “had so little sense of the honour conferred on him and such little appreciation of the value of the decoration.” However clearly Mr Niven had no idea of the wider diplomatic implications.

Other versions of how Queen Victoria’s gift to Lobengula was found

The South African Museum in Cape Town in its 1912 Annual Report has another version saying, “The Museum has acquired the gold necklace handed to Colonel J.W. Colenbrander in 1889 for presentation to King Lobengula and bearing the inscription on the pendant ‘From Queen Victoria to Lo Bengula, March 1889.’ Lobengula gave the chain to one of his chief Gaza Queens to wear. The relic was found among abandoned baggage bearing the canary yellow colour of the Matabele King, once the potentate over what is now Southern Rhodesia.” The King and his entourage fled the amaNdebele capital as the Salisbury and Victoria Columns advanced on Bulawayo.

The museum accession records that the chain was purchased, but no record of the price paid nor the source from which the chain was acquired can be found. It has also been said that the chain was discovered by a patrol during the rebellion in 1896, when it was found in the possession of a native woman who was driving some cattle. The cattle were taken as loot, likewise the chain.

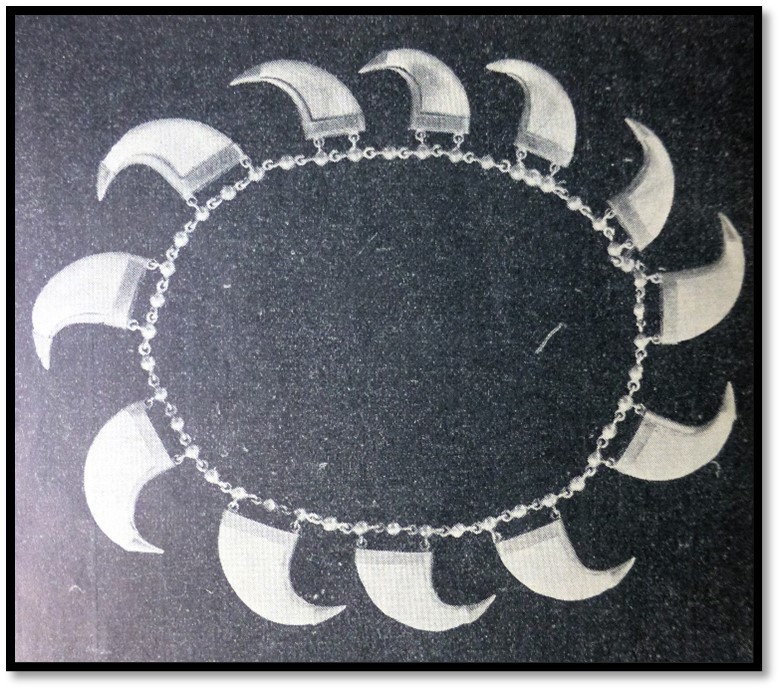

The necklace of lion claws presented by Lobengula to Sam Edwards

Lobengula presented Sam Edwards (1827-1922) with the necklace of lion claws when he made him an amaNdebele induna. Edwards was the son of a Bechuanaland missionary, the Rev Roger Edwards of the London Missionary Society and from 1848 was hunting and trading in Bechuanaland in the Lake Ngami area and on the Botletle river. In 1854 he escorted Robert Moffat to visit Mzilikazi. He farmed sheep in Natal until Sir T. Shepstone recommended him as guide, interpreter and transport manager to the London and Limpopo Company expedition to Tati. After this he traded on the diamond fields for around five years.

In 1881 he returned to Matabeleland to try and get a concession. Lobengula gave him the abandoned Tati Concession for £50 per annum. Edwards lived at Tati for the next ten years as managing director of the Northern Light Company. During this period he was made an induna and became effectively Lobengula’s ‘immigration officer.’ He retired from Tati in 1892, made a trip around the world and lived in Port Elizabeth (present-day Gqeberha) until his death on 21 June 1922.

Edwards gave the necklace to Lady Salomon and her sister, Mrs Christian of Port Elizabeth, presented it to the South African museum in 1921.

The necklace of lion claws given to Sam Edwards by Lobengula

References

Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir. November 1933

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd, Cape Town 1966

Note

[1] The article Why Lobengula sent envoys to Queen Victoria in the late nineteenth century is under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com