Home >

Mashonaland West >

Thomas Baines journey to Matabeleland in 1871 to obtain a written mineral concession from Lobengula and his return through the Limpopo Valley - Part 3

Thomas Baines journey to Matabeleland in 1871 to obtain a written mineral concession from Lobengula and his return through the Limpopo Valley - Part 3

In May 1871 Baines set out once again to obtain a written concession from Lobengula, the London directors of the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company insisted that a verbal agreement from the king was not enough; it need to be written, signed and witnessed. Wallis writes: “only a man as outstandingly unselfish as Baines would have had anything further to do with the company which, while requiring him to go again, did nothing to help him. It was £500 in debt. Neither directors nor shareholders would disburse further funds.

Lobengula’s succession was not 100% secure

Even after Lobengula’s coronation on 24 January 1870 Kuruman (Nkulumane or Kanda) continued to conspire against him from Natal where he was joined by some runaways from the Zwangendaba regiment, others had chosen to stay as bodyguards to Macheng at Shoshong. The Natal government was ostensibly neutral, but in fact backed Lobengula to ensure its own future commercial interests – the then known route from Durban being the best known. Baines writes: “If he really is the true heir, it is a pity he denied his identity when first asked because when the letters arrived stating this, the Matabele at once ceased to look to him and Lobengula could no longer refuse the dignity.”[i]

Baines future with the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company also becomes uncertain

On his return to Natal, Baines learned that the articles of the company allowed it to prospect, but not mine for gold. All efforts to float a new mining company (the South Africa Gold Fields Company) in London had failed as the directors were mistrusted on the financial markets after some dishonest and unreliable reports. The company was in debt and could not pay the salaries of Baines and Jewell, Watson and Nelson having left their employment. Nor could the company afford to pay for any more fieldwork in the northern goldfields, yet Edwin Oliver, the company secretary, still wrote to Baines and insisted that he obtain a written mineral concession from Lobengula to confirm his verbal promise.

In the face of such evidence, most would have quit, but not Baines such was his naïve faith in the northern goldfields and his trust in people.

Baines prepares for a new expedition

He sold any surplus equipment including most of his surveying equipment and more paintings. A trip was only possible because he was prepared to travel with very little and because people liked and trusted him. Tabler writes: “the fact that many friends and even strangers assisted him in spite of the deserved bad reputation of his company was a tribute to his virtues.” The surveyor-general of Natal, Dr Sutherland, helped with outfitting the wagons and Jewell was prepared to travel with him with Stephen Gee was hired as driver.

The expedition was underfunded from the start – they left short of trek oxen, their two wagons pulled by eighteen oxen instead of the usual twenty-eight and Jewell who carried their cash had only £3-£4. The only useable gun belonged to Jewell and of their two horses, one was sick.

“He had to cede 3,000 of his own shares before the Durban agent would advance money to pay the wagon drivers for the former trip and he had to give Watson a bond on his house in [King’s] Lynn as security for his wages. Unaware that the company had paid neither himself nor his officers since the first quarter, he generously offered to take shares in lieu of salary.”[ii]

Major David Erskine, then Natal colonial secretary, assisted by permitting all their mail – then subject to heavy postal charges, to travel under diplomatic mail. The wagons left Pietermaritzburg on 23 May 1871.

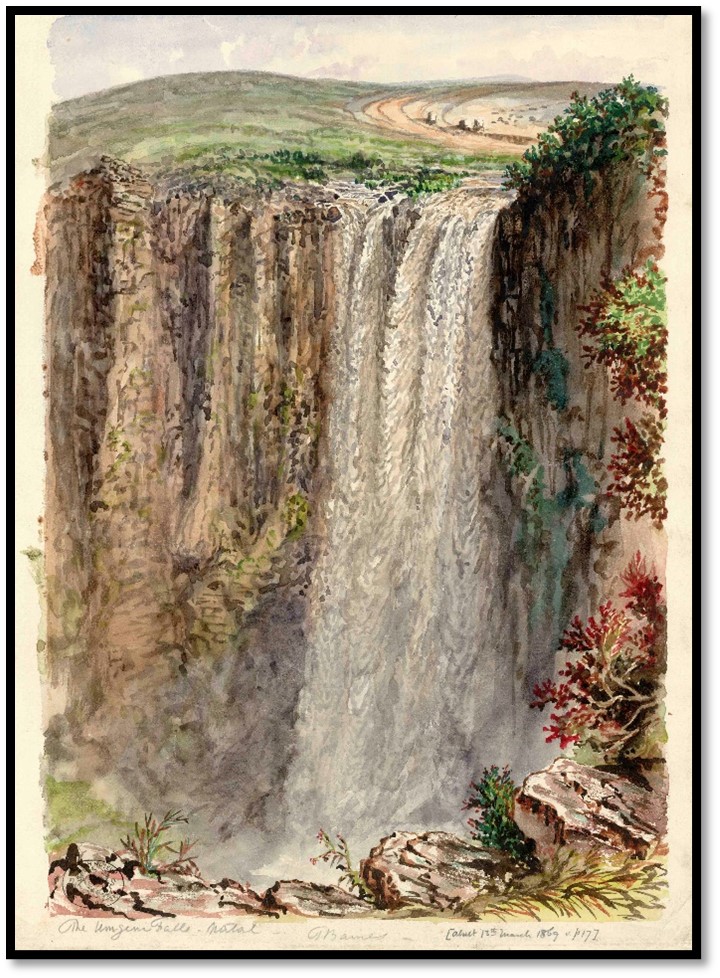

“In the afternoon we came insight of the Umgeni river, winding in bold curves through a broad valley and shortly after we passed the lower falls, the precipice, which is perhaps 30 feet high in some parts facing the south-east, so that it was in deep shadow and the numerous falls that poured over it only showed a light grey, except where they actually turned over the edge of the rock and the sunlight caused them to glitter like silver.”

NHM (London) Baines Collection No 1: The Umgeni Falls about 13 March 1869

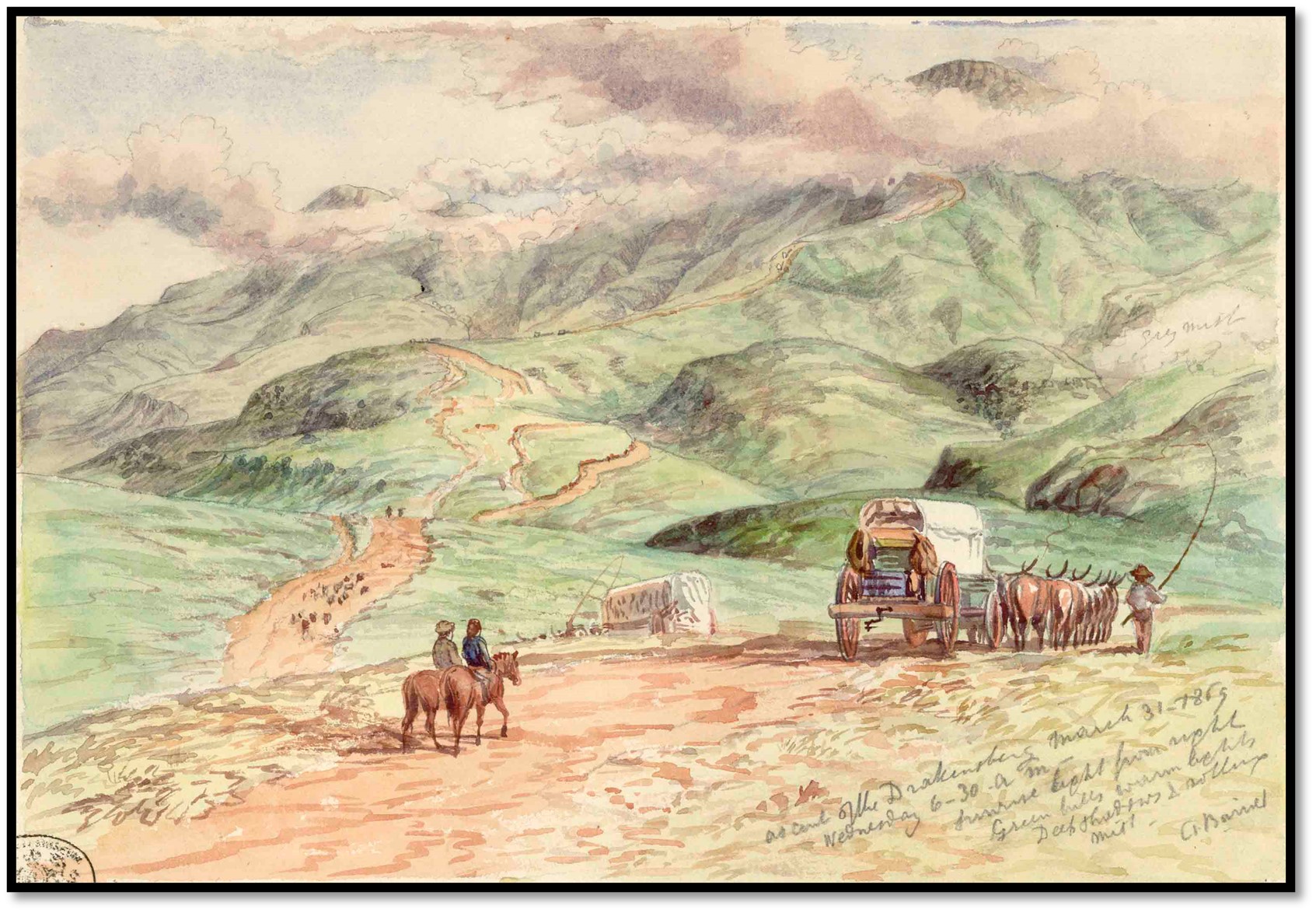

1 June 1871: “Climbed out and from the Drakensberg, thin clouds rolling round and veiling and unveiling the mountain peaks and denser masses resting in the valley below us, the effect of the sunlight as we looked down upon them being very picturesque. I enquired about the more direct road which goes to the east of Harrismith, but was advised to stick to the main one…

NHM (London) Baines Collection No 4: Ascent of the Drakensberg 31 March 1869

2 June: “Remained near Van Rensburg's kop all day to rest the oxen and get guns and other gear in order. I finished the map for Mr Van Zeller and marked in the boundary between the Portuguese possessions and those of the Transvaal…”

Once again Baines carries official letters to Lobengula

Baines diverted from the wagons to collect two letters at Potchefstroom written by Theophilus Shepstone and once again acted as unofficial envoy. The first recognized Baines as the bearer of a letter to Lobengula and requested all British subjects to remain neutral on the question of the amaNdebele succession.

The second thanked Lobengula for his kind-hearted treatment of British citizens but warned him that Kuruman still plotted to force him out but that the Natal administration would not take sides and would remain impartial on the succession question.

Baines travelled with Francisco Van Zeller, the Portuguese consul general who gave Baines another letter for the chief’s in the interior stating the Portuguese had no aggressive intent towards them. Van Zeller also made a loan to Baines’ expedition.

On his way through the Transvaal he met Paul Zietsman, a hunter friend from their 1869 journey before arriving at Thorndale, Henry Hartley’s home on 20 June although Hartley with his wife and son Harry had already left. Fred and Tom Hartley who farmed nearby welcomed Baines and gave him salted meat before they were joined by Jewell and Gee with the wagons leaving the next day

Baines and Henry Hartley meet up again

Baines rode on alone because he wanted to catch up with the Oude Baas and when he did at the Elands river Hartley was surprised as Nelson had told him the company had no funds for more journeys or even to pay the bill Baines had given him on the 1860 journey for a salted horse. Baines could only apologise and they discussed future prospects and Hartley returned six of Baines’ oxen he had kept for him and they agreed to meet again at the Limpopo river.

On 30 June Hartley and Baines at the Marico river[iii] found Glass with three wagons taking a steam engine and stamp mill to the Tati goldfields on behalf of Charles Hart. The wagons were overloaded and progress was slow, Hart had gone on ahead taking the trekking tackle necessary for the steep banks of the Marico river. Arkle, a newly recruited engineer of the London and Limpopo Mining Company asked to travel on with them.

Baines and Hartley did not enter Shoshong; Nelson had two guns confiscated by Macheng the previous year and kept to the Hunter’s Road. Baines walked ahead with Arkle and they caught up with Hart’s party at the Towani river, where a horse had just been badly mauled by an old lioness that Hart had shot.

Arrival at Tati – more financial difficulties

They trekked on meeting several parties from the Zwangendaba regiment leaving Matabeleland before reaching Tati on 18 July with Baines delivering the mail to the Europeans still resident. They included R.N. Acutt,[iv] Alexander Brown,[v] Cooksley,[vi] Franklin, August Griete,[vii] George Hall,[viii] C.J. Nelson[ix] and the remaining Australians at Todd’s Creek.

Acutt had orders not to accept any bills on the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company. Baines needed supplies and thought of leaving six of his oxen as security for a £60 bill that had been accepted from John Lee. Hartley came to his rescue, accepting the bill, buying four muskets so Baines could pay his servants and giving supplies on credit. With no money, Baines went hunting with Gee and Hart and shot a fat cow giraffe.

Griete came in from the Blue Jacket mine about 3 miles north-east of Tati and invited Baines to visit. They descended the shaft on a single pole ladder that was sunk on an old native working but had struck water and the dip of the quartz vein had altered, but visible gold was seen in the samples they examined.

Henry Hartley had his last hunting season in 1870; he was now going to the Limpopo and Marico rivers to meet his son-in-law Thomas Maloney and search for diamonds in the river gravels that they believed were similar to those at the Vaal river diggings.

Baines and Jewell left Tati on 2 August after a farewell evening with Hartley.

Baines meets John Lee at Mangwe

On 4 August Baines was at Mangwe to receive a warm welcome from Lee and his new wife. They discussed the company’s future prospects, and Lee was persuaded by Baines’ optimism and because Edwin Oliver, the company secretary had confirmed Lee’s appointment as company agent if a written concession was obtained from Lobengula. Current prospects were poor, with the company’s credit rating at nil, Nelson having quit and mining not yet attempted, but both Baines and Lee hoped a written concession would help the company raise funding on the London financial markets and salvage the situation.

They sorted the goods they had left with Lee and Lee’s son-in-law David Jacobs shot two eland and supplied them with meat and they set off on 8 August with Lee and his young wife to meet the king.

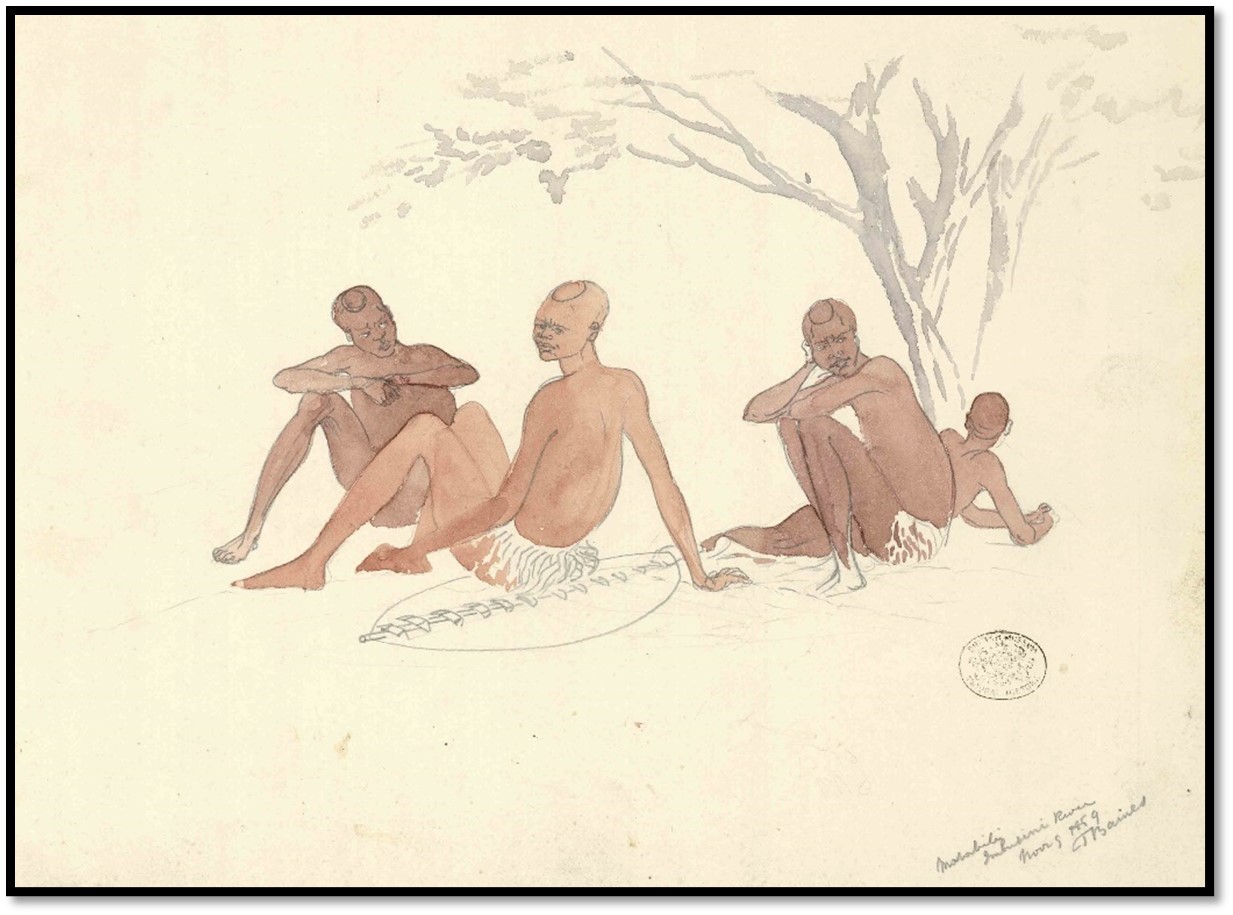

NHM (London) Baines Collection No 71: Matabili at the Umbusini river

The official letters from Shepstone are read to the king

They arrived on 11 August; the king was at the Umzingwane river. Those present included Harry Grant,[x] Karl Meyer,[xi] William Francis,[xii] Cunningham, Daniel Kisch[xiii] (now the King’s secretary) and Jacques Beaulieu, his French chef and George Phillips.[xiv] Revd J.B. Thomson was fetched from Hope Fountain by Jewell. Baines gave him a tombstone for the members of the Durban Gold Mining Company who had died of fever at Inyati.

Next day Lee and Baines read and translated each of the letters from Shepstone, Van Zeller and one from Hartley to the king with just his sister Ling En or Ningi present. Lobengula had many questions for them about Kuruman (or Kanda) and asked that Shepstone’s letter be kept confidential. At Lobengula’s request, Baines wrote replies, despite Kisch’s protests. Shepstone was thanked for his warnings and asked not to assist Kuruman and it accused Mangwane, another of Mzilikazi’s sons, of being in exile to evade an adulterous relationship with one of the late king’s wives. Van Zeller was thanked for his letter repudiating the Quelimane governors claim that treaties with the native chiefs in Mashonaland could only be legally made with the Portuguese authorities at Sofala. There was a friendly reply to Hartley and a letter to the president of the Transvaal Republic M.W. Pretorius. All were signed by Lobengula with his wood-cut seal cut by Baines.

Lobengula’s wood-cut seal carved by Thomas Baines

Macheng, the Chief of the Bamangwato continues to defy Lobengula

There was a poor relationship between Macheng and Lobengula and many thought an attack on Shoshong would take place. Macheng supported Kuruman (or Kanda) and tried to resist any friendly relations between the amaNdebele and the Natal government. Baines volunteered to escort Lobengula’s messengers to Natal, but he was asked instead to take letters out of Matabeleland by a road that skirted the tsetse-fly belt to the Limpopo river and so avoid the usual route through Shoshong. No messengers would go as Lobengula thought roving bands of Bamangwato hunters would kill them.

Lobengula signs a written mining concession

Shepstone’s friendly letter and persuasion from Lee led to Lobengula granting a written mining concession to the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company. The king accepted Baines’ explanation that funds and machinery had been delayed only temporarily and on 29 August 1871 signed the document with his mark and seal. The document confirmed the verbal mining rights, but no entitlement to land and was read aloud by Lee before being witnessed by Betts,[xv] Jewell, Lee and Phillips.

Tabler states[xvi] that the concession was never used; Baines could not interest other parties and the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company sold the concession to a group of Transvaal speculators who sold it on to the Matabeleland Company (under the control of Sir John Swinburne and formerly the London and Limpopo Mining Company) and it was finally sold in 1890 to the British South Africa Company under Cecil Rhodes.[xvii]

Almost no further prospecting was carried out in Lobengula’s domains for the remainder of the 1870’s.

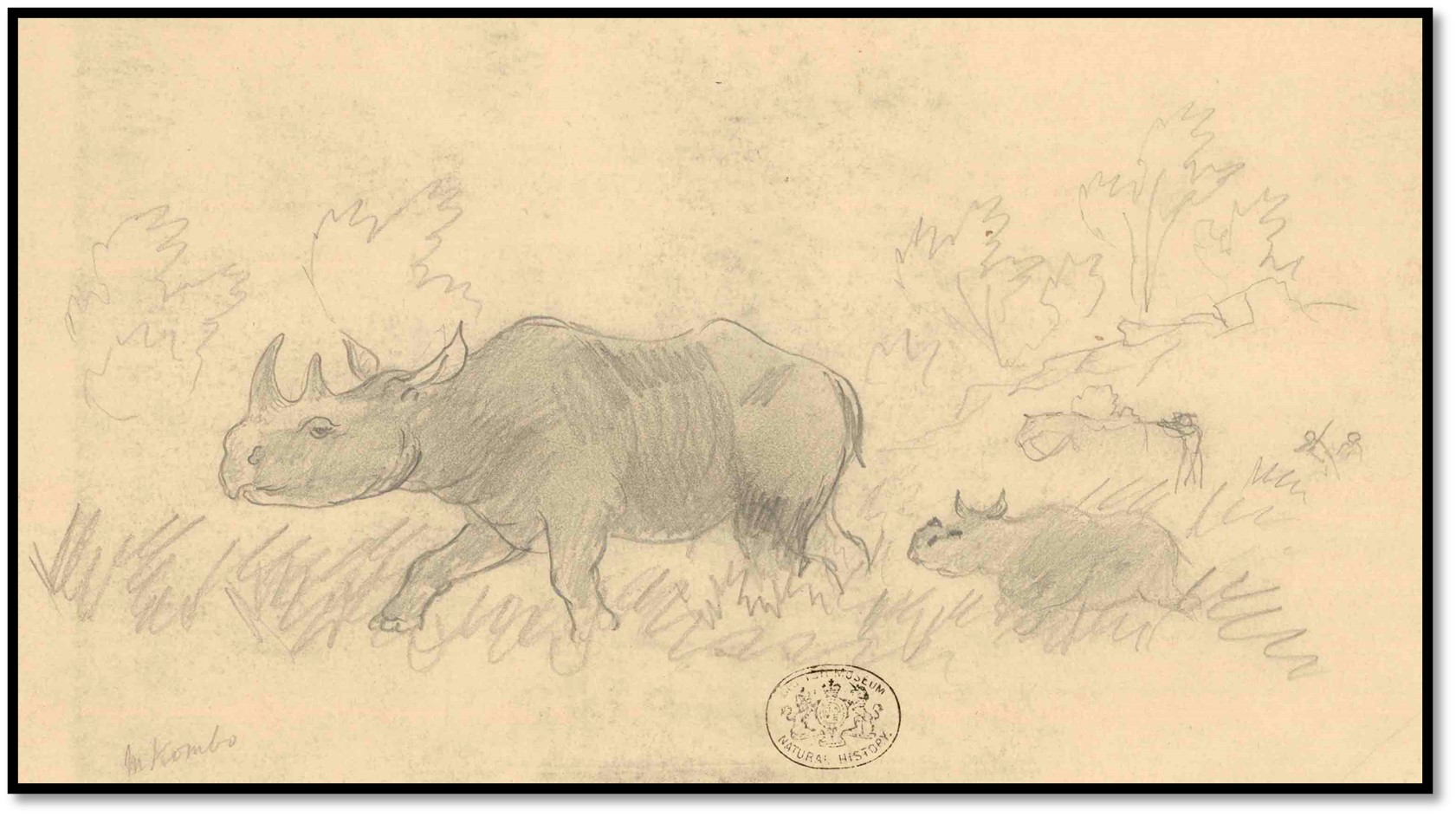

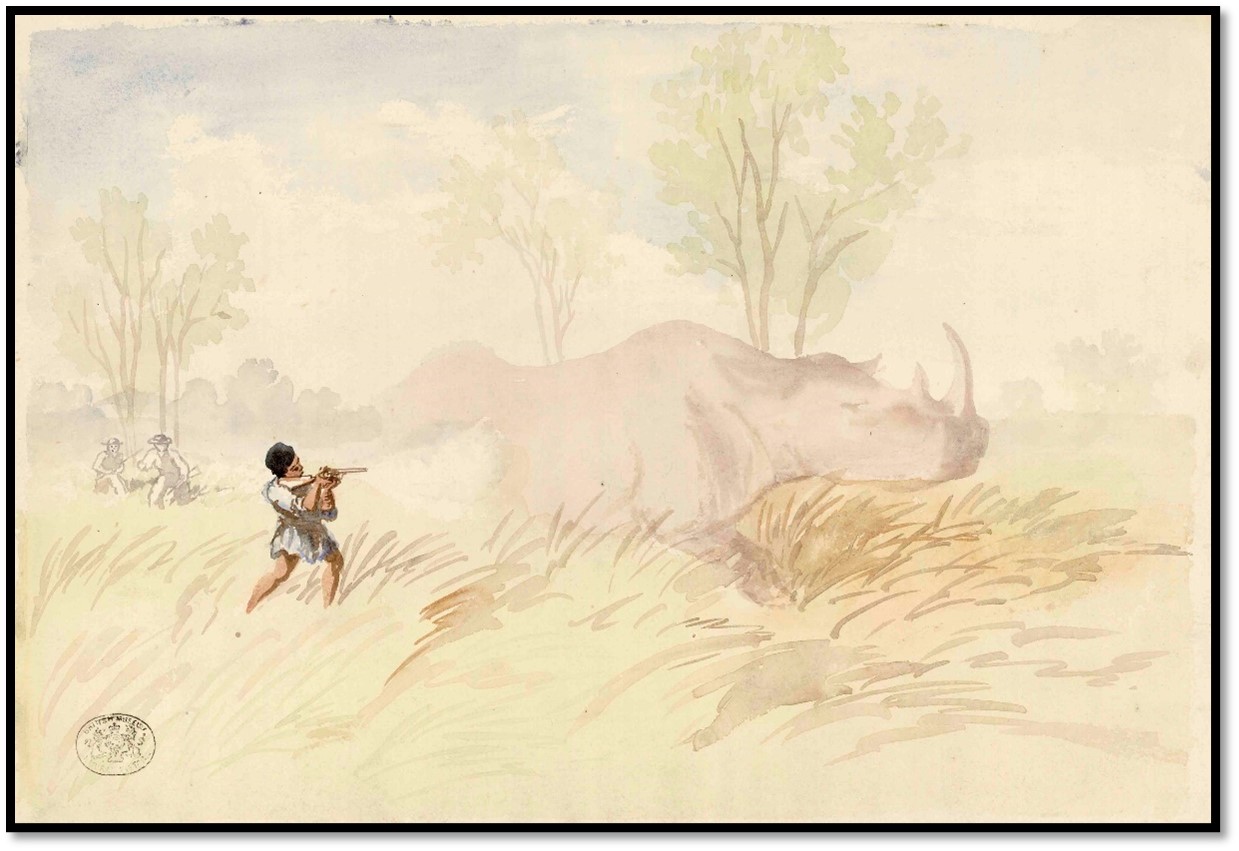

NHM (London) Baines Collection No 115: white rhino and calf, 1 Sept 1870

The Baines party left the king’s capital for Mangwe

On 31 August final gifts were handed over to the king; he gave beef and sheep in return and they trekked to the king’s storehouse where Phillips paid over 200 lbs of ivory owed to Jewell for his gun, more ivory went to Lee for a salted horse. Baines met with Ncumbata who had been regent in the interregnum and found him, despite his age, with all his mental faculties.

The wagons left for Mangwe accompanied by Revd Thomson’s wagon going to buy grain. Thomson, at Baines request, had written to Oliver, the London company secretary, to say the concession was written and signed and enjoyed royal favour. By 8 September Baines was at Mangwe and paid off his four Makalakas and hired five others for the return trip to Natal. He and Jewell then set off for Tati to give the kings letters to Nelson who would send them south

Tati in September 1871

At Tati Charles Hart was building a house and laying the foundation for his steam engine and stamp mill ¾ mile away.[xviii] Baines advised him to give Lobengula a gift and get his permission to use the machinery through John Lee as go-between.

Those living at Tati included:

London and Limpopo Mining Company Glasgow and Limpopo Company

E. Arkle (Engineer) A. Brown

Franklin (Storekeeper)

H. Gren (Asst. miner) Australian miners

A. Griete (Miner) A. Crawford and W. Runyard at Todd’s Creek

C.J. Nelson (Manager and mineralogist) G. Hall, H. Dobie, H. Smith, C. Brown, J Hagen-Meyer

R. Noble Acutt (Head storekeeper)

Charles Hart party Others

Mr & Mrs Hart Griqua party

R. North (Engineer) Pat McGillewie (brother of Henry who died at the Serui river

S. Stevenson Tom McMaster who came in from the Mababe Flat with 1,200 lbs of ivory and ostrich feathers

Trekking to the south via the Limpopo river

By 19 September Baines and Jewell were back at Mangwe and preparing their wagons. They were joined by Henry Byles[xix] who had returned from hunting on the Ganyana[xx] (Hunyani / Manyame) river. Baines’ Zulu driver Matchaan had left to work for Nelson, Karel Lee, a son of John Lee, was employed as a hunter and driver.

On 26 September a group of wagons comprising those of the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company (Baines, Jewell, Gee and Karel Lee) Byles and his wagon, the wagon of the Boer hunters Christiaan Herbst[xxi] and Piet Lee[xxii] and the wagon of father and son, de Smidt.

Baines wagon stuck at the Mangwe drift, they did not have a full span of oxen, the others freed it. The hunters shot two giraffe, when Herbst approached the second and grasped its horns, it rose and threw him some distance. They trekked initially down the east bank of the Mangwe, switching to the west bank on the 30 September down to its junction with the Semokwe (Simukwe) river where they met James and his son George Jennings[xxiii] with a Boer hunter Potgieter at their campsite. At this time of year the Semokwe was dry and Potgieter told Baines the tsetse-fly country ahead could be safely negotiated.

Baines was still short of oxen, but he had nothing to offer and the hunters would not accept bills on the company. However Byles bought two oxen from James Jennings and lent them to Baines whilst they travelled together and George Jennings sold another two oxen to Baines’ on his personal credit. The party followed the Semokwe on its west bank and shortly before its confluence with the Shashi (Shashe) crossed to the east bank on 7 October, the Boers and Byles hunting buffalo for meat.

The others crossed the Shashi at the confluence, but Baines and Jewell crossed at an easier drift a little further down and a campsite was formed south of the river where the trek gear was overhauled and some fishing carried out in the river’s pools. The hunters, except Byles who was also going to the Transvaal, then turned west up the Shashi to hunt elephant.

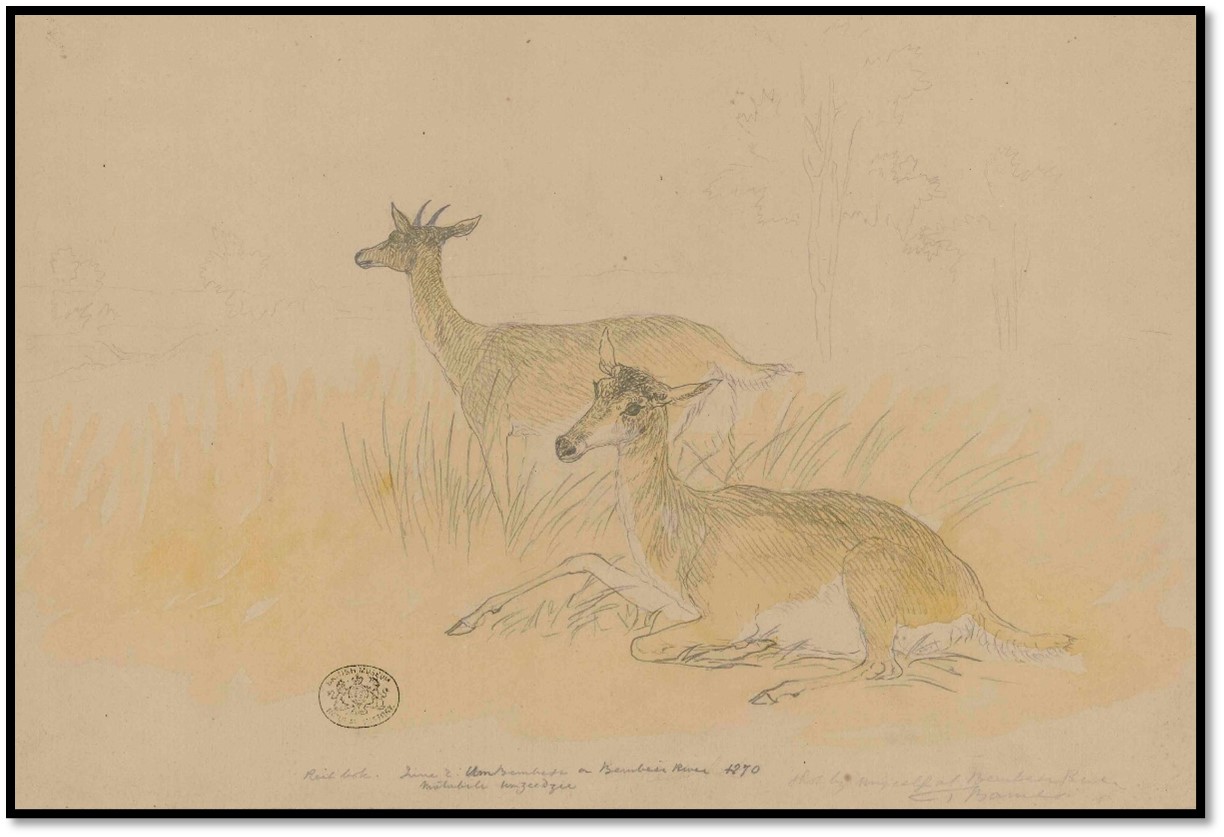

NHM (London) Baines Collection No 142: Two Reitbok (Reedbuck) at Bembezaan river 2 June 1870

Baines, Gee and four of the servants needed to establish the extent of the tsetse-fly belt and trekked 54 km to the Maklautsi river. The way was free of the fly and navigable for ox-wagons with water in rock pools along the way and game was plentiful. The wagons negotiated the countryside whilst the others scouted for the deadly fly and speculated on who had brought a wagon some time earlier from the Limpopo to the Shashani and then returned leaving a double track. Local Khoisan attracted by the vultures around an antelope shot by Byles stated they belonged to a Transvaal hunter named Hendrik Duvenhage. They said they were too afraid of Macheng’s revenge on them if they acted as guides to the party.

After they wandered into a fly area Jewell’s horse and the oxen were washed down with an ammonia solution, thought to be a preventative and extra care was taken to keep watch over the animals - they were only taken to water after dark when the tsetse-fly is inactive. They noted some of Duvenhage’s camps were in fly areas, only learning later that his oxen had been fly-struck and so were doomed in any case. Baines, Byles and five servants walked ahead and reached the Pakwe river where on the 21 October they found a good waterhole named Byles pool by Baines.

The wagons followed on and on the 28 October the Limpopo river was reached near where the Suka river joined from the north-west as a tributary. From here they travelled west upriver guided by Khoisan travelling at night across the known fly-belts, but despite these precautions Baines lost nine oxen and Byles lost an ox. At a drift (sometimes called Commando drift) they crossed to the southern side of the Limpopo river and entered the Transvaal Republic.

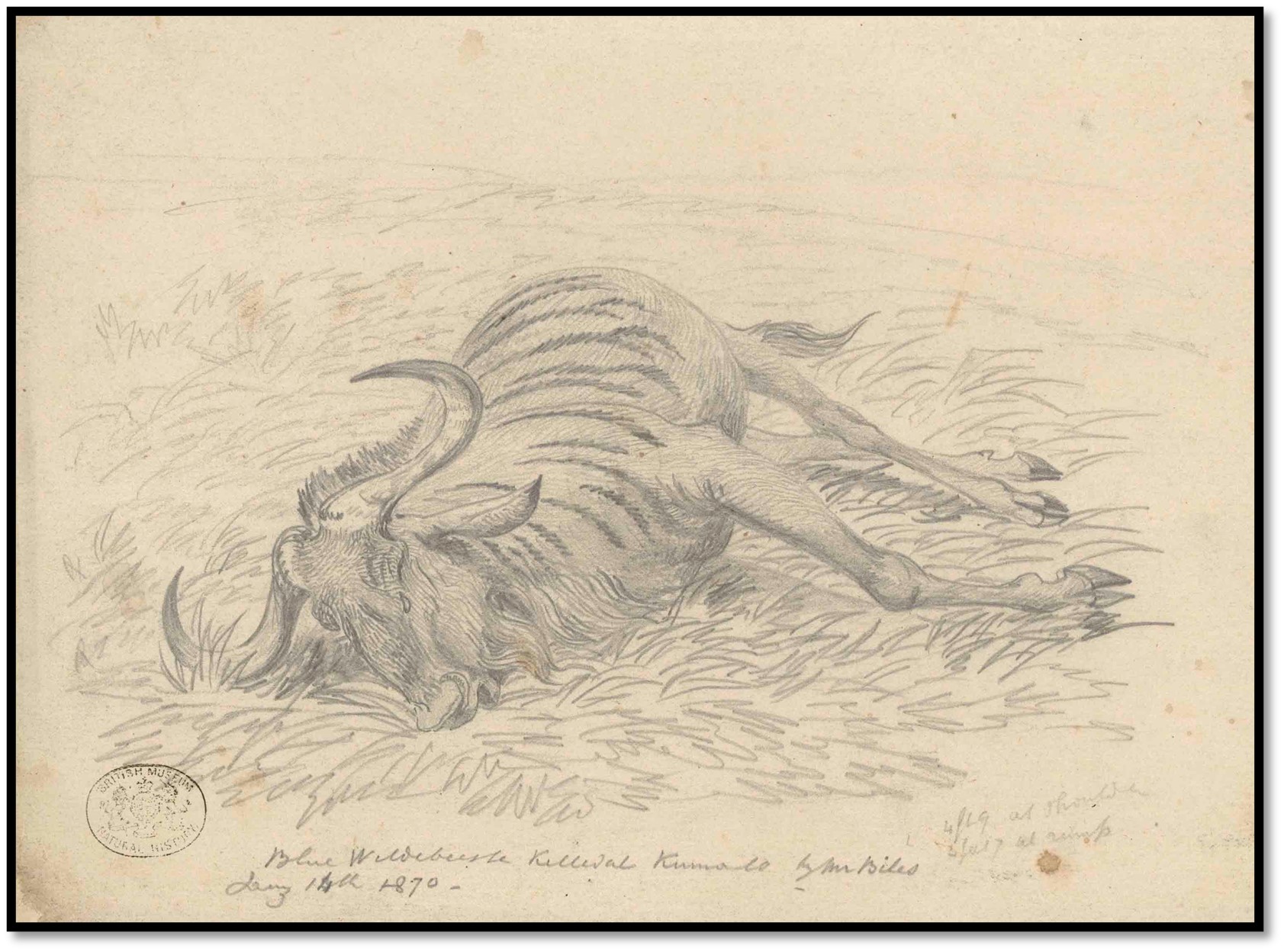

NHM (London) Baines Collection No 144: Blue Wildebeest shot by Henry Byles 14 Jan 1870

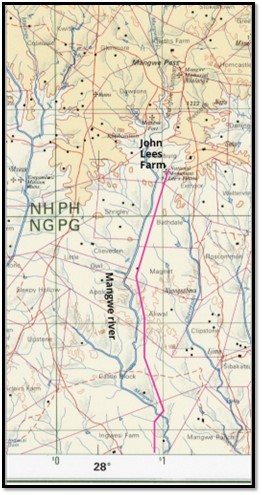

Map 1 – adapted from 1:250,000 map sheet SF-35-7 Mphoengs; this map is used with consent from Window on Rhodesia with the site name: https://www.rhodesia.me.uk. Route taken by Baines / Byles party down the Mangwe river

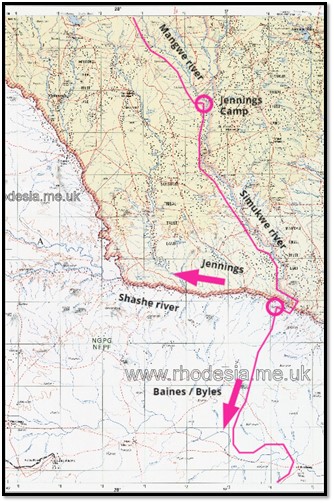

Map 2 – adapted from 1:250,000 map sheet SF-35-7 Mphoengs; this map is used with consent from Window on Rhodesia with the site name: https://www.rhodesia.me.uk. Route taken by Baines / Byles / Jennings party down the Simukwe river to the Shashe

On comparatively good tracks they reached Pretoria in mid-November where Byles[xxiv] and Baines parted ways. Lobengula’s letter to the Natal government were sent on by post, that to the Transvaal government was delivered. Baines and Jewell went on to Hartley’s farm at Thorndale.

The bills drawn on the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company and given by Baines for salted horses and food had been dishonoured in London, Hartley did not blame Baines, but withdrew any support for the company. Karel Lee was paid for his service with three oxen worth £5 each and Baines left a horse and wagon with Hartley in partial payment.

Return to Natal

Baines and Jewell stayed in the Transvaal until mid-February 1872, Baines supporting them by selling paintings and by March, helped by generous friends as they were now without funds, they were back in Natal.

Here they heard of Kuruman’s (or Kanda) attempt to overthrow Lobengula as ruler of the amaNdebele. Kuruman had left Natal with a small group of followers in June 1871 arriving in Shoshong a month later. He convinced Macheng that the amaNdebele would flock to his cause and with a handful of rebel amaNdebele and Macheng supporters advanced to the Shashani river. But the king had plenty of time to prepare his forces and when Kuruman’s warriors heard an amaNdebele impi was approaching they quickly retreated. Kuruman was forced to seek the protection of Matjen, his supporter. However in 1873 the Bamangwato rose in support of Khama and expelled their untrustworthy chief and Kuruman was forced to flee and spent the rest of his days in obscurity.[xxv]

NHM (London) Baines Collection No 124: A rhino hunt between the Sebakwe and Bembezaan rivers, 6 Oct 1870

The company’s financial woes continue

Bad news awaited Baines, attempts to float the South African Goldfields Company to succeed the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company had failed and the new company rejected the debts of the old company leaving Baines responsible for the debts incurred. Many of the creditors because they liked Baines, did not press their claims, but others did.

Baines’ wages held in London had been used for advertising the flotation of the South African Goldfields Company, his house there inherited from his mother, was pledged to Watson for his wages, the recent 1871 trip had been financed by him selling paintings.

Then the mining machinery arrived at Durban, but there were no funds to pay for its transport to Mashonaland. If the company had ceded its rights to Lobengula’s mineral concession, Baines would probably have found friends in Natal and the Cape to fund these expenses and provide working capital for a mining venture, but they would not. It was impossible to expect Baines in Natal to do what the directors could not do in London. As Baines wrote in one of his rare protests, any one of the directors could privately have provided the money needed to begin operating at Hartley Hills, but they would not.

Baines financial problems also remain

Hartley wrote of Baines: “there was over much of the milk of human kindness in his bosom, he was no longer young and must look to his future.” Sanderson, the surveyor-general told him to cut the connection with the company that hampered him and wasted his time. John Robinson of the Natal Mercury wrote: “you are one of those men who work for the world rather than for yourself and I regret it so often happens that the world requires such services by ingratitude.” Both Hartley and Lee made losses and were not repaid, but both accepted their losses rather than embarrass their good friend.

Edwin Oliver, the London secretary had no scruples and said how nobody would buy the Goldfields Company shares in England, yet suggested they be used to pay off the creditors in Natal. Baines protested at the lack of conscience and wrote about the “daily humiliation” and that he was “thoroughly ashamed” of the company.

Merchants in Port Elizabeth expressed an interest, but the demands from London killed off their appetite. Baines all the while was painting for old friends and new commissions to raise funds and he gave public lectures on gold mining and the Victoria Falls. He might have raised enough funds locally to transport the mining machinery to the Eersteling goldfields[xxvi] near Pietersburg (present-day Polokwane) but the company directors made excessive demands.

Baines heard of another gold find in the remote Injembe district on the Tugela, 130 km from Maritzburg. His companion, Osborne an engineer soon went down with fever. Conditions were hard with no roads, rocky valleys and dangerous cliffs a thousand feet above the Tugela, but Baines loved it and examined the riverbeds and outcrops and old mine workings. There were unmistakable signs of gold, but the deposit did not seem payable and he returned to Durban by 14 July 1873 having paid for the cost of the trip out of his own pocket.

Visit to Zululand for Cetewayo’s coronation

Baines was back only ten days when he heard Shepstone was about to go to Zululand and crown Cetewayo, king Panda’s successor. By going as the ‘special correspondent’ to the Natal Mercury he could sell more paintings and he travelled by train and road with the Durban Volunteer Artillery as ‘artist and geographer.’

Cetewayo much alarmed, retreated into the interior and when he failed to appear at the meeting place Baines borrowed a pony and with two others went to visit John Dunne, the chief’s white adviser where they learned the king was afraid of treachery. After numerous failed meetings the king appeared on 28 August 1873 and he and Shepstone met in a tent. Negotiations continued on and off until on 1 September the coronation took place. “The new laws were read and proclaimed, the myriads of warriors, like one man, raised aloft their Shields and rattling on them with their staves signified their ascent and great acclamation.”[xxvii]

Thomas Baines: The Victoria Mounted Rifles at Rendezvous Camp, Tugela river, August 1-8, 1873. Presented to the Corps by their friend the artist who sits on the right

In return for hospitality during this trip, Baines presented the above water-colour with the artist sitting on the right. Back in Durban, Baines began to work again on his paintings…the adventure had rundown his funds. Kisch, once the storeman at Tati, then Lobengula’s secretary, now had a photographic studio in Durban and sold Baines paintings on commission.

If the London directors did not appreciate his efforts, others did

Dr Petermann of the Geographical Institute, Gotha, incorporated Baines’ maps of Matabeleland and Mashonaland into his own, published Baines’ notes in his Mitteilungen and wrote to the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) to recommend Baines for a gold medal. The RGS did publish his maps and notes in its Journal and Proceedings and awarded him a gold watch for his “long-contained services to Geography” and he was elected Honorary Fellow for life in 1874 but never received a Gold Medal.

Baines financial situation slowly improves and there are grounds for optimism

By 1874 his financial situation was improving. Osborne, who had found a job, heard that Baines had paid the whole expense of their Injembe trip, sent Baines his share of the expenses. Jewell had found him a job. Many of the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company debts had been paid off. The London directors had authorised Baines to deal with the mining machinery still sitting at Durban docks in any way he chose, except selling it. Along with Richard Vause, the latest Durban agent, he had lodged a claim upon the machinery in case the directors tried to sell it. He feared Lobengula might withdraw his written mining concession as nothing had come of it. The company had sent a gold signet ring to Lobengula, also a second-hand case of duelling pistols that were in such poor condition that Baines kept them until they could be repaired.

In a letter to his sister in June 1874 he said he had just completed a large map of the goldfields in seven sheets, 10 x 7 feet; he was beginning to “get his head above water” after “rather a hard pull for the last ten months.” A small crushing plant and steam-engine was being made for him in Durban and was already half paid for and he hoped to take it to Hartley Hills to reassure the king that the concession was not being neglected. He was also writing up his diaries for publication…this would be The Gold Regions of South Eastern Africa published after his death.

Osborne wrote from Port Elizabeth saying merchants were: “perfectly willing to advance at a moment’s notice £12,000” as long as there was no interference from the London directors. Baines offered to serve a new company for a year without pay and if it succeeded the shareholders could pay him as they thought fit. But when he went to Port Elizabeth the merchants saw that Baines could not give them a legal right to Lobengula’s concession and negotiations with London dragged on without any results.

The last years

Baines met a miner in early 1875, Morgan, who was willing to travel to Mashonaland with him. He wrote to Lobengula explaining the reasons for the delay and said he hoped to be at Tuli in June. Then a Church of England parson, Rev W. Greenstock agreed to share travelling expenses to investigate the possibility of another mission station in the interior.

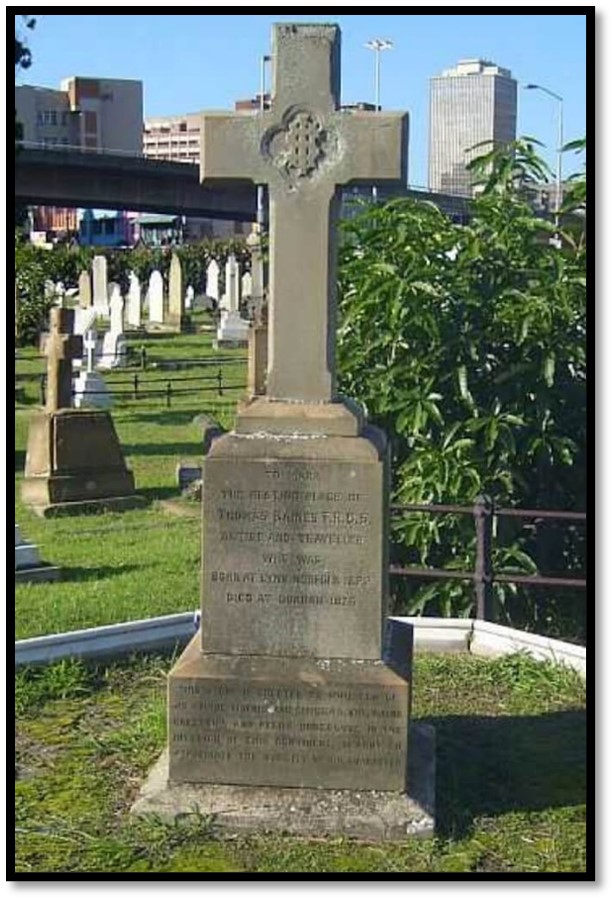

In March he had his wagon loaded up in the street where he lodged with his aunt, Watson’s mother, ready for his third trip to Mashonaland and the mining claim at Hartley Hills. But in April he caught dysentery and died on 8 May 1875 and was buried in the old West Street cemetery at Durban.

Thomas Baines grave at West Street Cemetery, Durban

There were crowds at his memorial service in Kings Lynn as the family were well-known. But in Durban when Richard Vause, the mayor of the city and company agent, appealed for funds for a memorial there was a very meagre response. It was seven years before his memorial arrived with its the epitaph stating: “comrades, who during hardships and perils undergone in the interior of the Continent, learnt to appreciate the nobility of his character.” The mural stone sent out by Robert White[xxviii] in 1883 testified to “the unselfishness, simplicity and nobility of his character” and concluded: “He was a man to whom the wilderness brought gladness and the mountains peace.”

His tombstone states his birth was in 1822, but his mother records it in the family bible as 27 November 1820.[xxix]

Acknowledgements

Once again I have Tabler and Wallis to thank for their meticulous and extensive research and well-documented writings on those hunters, traders and travellers of 1860 – 1870 in the region then called Zambesia.

References

F.O. Bernhard. Karl Mauch, African Explorer. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd, Cape Town 1971

Hall R.N. and Neal W.G. The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia. Methuen, London, 1902

R. Summers. Ancient Mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia, 1969

E.C. Tabler. The Far Interior. A.A. Balkema. Cape Town, 1955

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd Cape Town, 1966

J.P.R. Wallis (Editor) The Northern Goldfield Diaries of Thomas Baines Volumes 1 – 3. Chatto and Windus, London 1946

J.P.R. Wallis. Thomas Baines, his life and explorations in South Africa, Rhodesia and Australia 1820-1875. A.A. Balkema, Cape Town 1976

Notes

[i] Northern Goldfield Diaries Vol 3, P599

[ii] Northern Goldfield Diaries, Vol 1, Pxvi

[iii] The Marico river forms the present-day border between South Africa and Botswana and is joined by the Crocodile river where it becomes the Limpopo river

[iv] Acutt was the company secretary of the London and Limpopo Mining Company

[v] Brown was storekeeper after Kisch’s dismissal to the London and Limpopo Mining Company and in charge of operations after Dr Coverley departed

[vi] Cooksley, a transport rider, left Tati a few days later for Potchefstroom and Baines sent out letters with him

[vii] Griete, the original miner for the London and Limpopo Mining Company who dug their shafts at Hartley Hills was

Now working the Blue Jacket reef

[viii] Hall came to South Africa with the coaches of Cobb and Company that ran between Port Elizabeth and Kimberley – the same coaches were later operated by Doel Zeederberg

[ix] Nelson, the mineralogist and mining engineer employed initially by the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company and now by the London and Limpopo Mining Company

[x] Grant traded in Matabeleland 1870-93 and built Lobengula’s house

[xi] Karl Meyer, hunted elephant with Paul Zietsman, worked as a blacksmith near Lee’s place at Mangwe in the rainy season

[xii] Francis was trading at Bulawayo in 1870 and established the well-known firm of Francis and Clarke at Shoshong from 1872

[xiii] Kisch was the London and Limpopo Mining Company’s storekeeper until he knocked Sir John Swinburne to the ground in an argument. He was trading in Matabeleland in 1870 and for a time acted as Lobengula’s secretary

[xiv] ‘Elephant’ Phillips was an old-timer in Matabeleland and first visited in 1864. A partner of George Westbeech until the latter’s death in 1888. Hunted elephant and traded in Bulawayo, at Lobengula’s succession on 22 January 1870, witnessed the Wood-Chapman-Francis concession at Bulawayo. Left Matabeleland in 1890 after having lived almost continuously in Matabeleland for 25 years.

[xv] Betts was a trader in Matabeleland in 1871

[xvi] The Far Interior P375

[xvii] For full details see the article The British South Africa Company under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xviii] Hart could not get enough ore to make his venture a commercial success and sold the steam engine and battery to James Cruikshank of Shoshong and left the country

[xix] Byles was an elephant hunter and trader. In 1870 he was hunting with Willie Hartley and O’Donnell when they died of fever at the Chirundazi stream. Traded throughout the 1870’s in Matabeleland and the Zambesi Valley.

[xx] The Manyame river was also called the Panjamey as well as Ganyana

[xxi] Herbst was an Afrikaner hunter who had often trekked from the Zoutpansberg to the Sabi river

[xxii] Piet Lee, a hunter and son of John Lee

[xxiii] James Jennings II and his sons Jeremiah, James III, John and George were all hunters and traders from about 1867 to 1871 and well-known to Hartley and Baines

[xxiv] Byles was at the Eersteling goldfields in December 1871 where he lived chiefly by hunting and supplying the miners.

[xxv] The Far Interior, P380

[xxvi] the Volksraad proclaimed Eersteling a public diggings and christened the area the Marabastadt goldfield.

[xxvii] Thomas Baines his life and explorations, P219

[xxviii] White was a friend from Grahamstown days and when in England sold many of Baines’ paintings

[xxix] Northern Goldfield Diaries, Vol 1, Px

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: