Home >

Mashonaland West >

Thomas Leask’s elephant hunting trip to Matabeleland and Mashonaland in 1866 from his diary

Thomas Leask’s elephant hunting trip to Matabeleland and Mashonaland in 1866 from his diary

Introduction

Thomas Leask made the following journeys into the interior: Bechuanaland (1865) Matabeleland and Mashonaland (1866, 1867, 1870) and the Zambesi Valley (1868, 1869) and they are well-edited by J.P.R. Wallis in The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask.

Leask landed at Durban on 9 January 1862, but his early diaries were lost, and his diary writings start from 1864 when he quit paid employment and undertook three trading trips into Basutoland in 1863-4, “My business among the Basutos was principally barter, giving goods in exchange for horses, oxen, sheep, goats, corn, mealies and sometimes cash. The natives bought good and useful articles such as blankets, saddles and clothing of all kinds. The women bought only beads, buttons and brass wire.”

Wallis thought Leask probably wrote his diaries up the same day in the evening when supper was being prepared. They are always written in a light vein, as though describing his thoughts to a family member, they are both frank and humorous, and he often tells a joke against himself. Unlike Thomas Baines and Frederick Selous, he was not particularly interested in describing accurately the geography, geology, flora and fauna of the landscape around him; his chief interest seems to be the people he kept company with. Who he met, their characters, the gossip around the camp-fire, were his interest, but his meetings with the various traders and hunters and the native chiefs all provide an interesting and useful account of the goings-on in the interior in the 1860’s.

I have used his diary notes, although they are often shortened, and of course, they focus on his elephant hunting experiences.

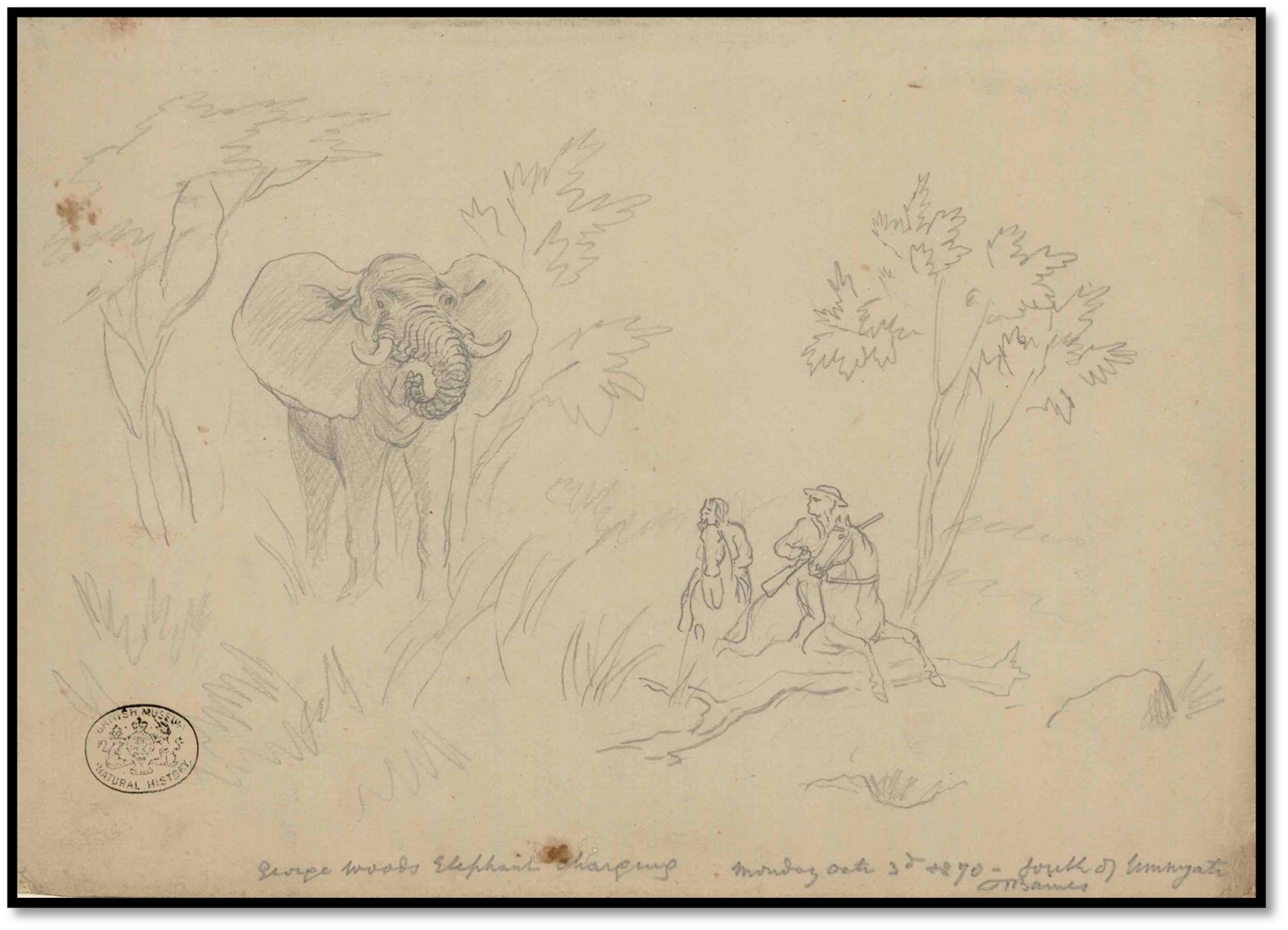

NHM (London) No 104: Thomas Baines, Elephant charging George Wood 3 October 1870

Prelude to his first hunting trip in Matabeleland / Mashonaland

He found crossing the Drakensberg in winter not only arduous, but also dangerous, as the Basutos[i] and Free State Boers were constantly skirmishing. In 1865 he agreed to join a friend growing coffee in Natal, but the intended partner left for England, so with George Phillips and a Mr Pike, he took his remaining stock of horses over the Drakensberg through Harrismith, “Very cold this morning. The ground white with frost. Horses and oxen looking miserably cold” on their way to Potchefstroom.[ii] The horses kept wandering away at night seeking shelter from the cold. “Seeing watches are to be kept all night we took care to provide plenty of fuel. When we outspanned every man and boy went cow-dung hunting…Certainly it is not the most cleanly occupation to gather such fuel, but hands were made to be used and water made to clean them when dirtied.”

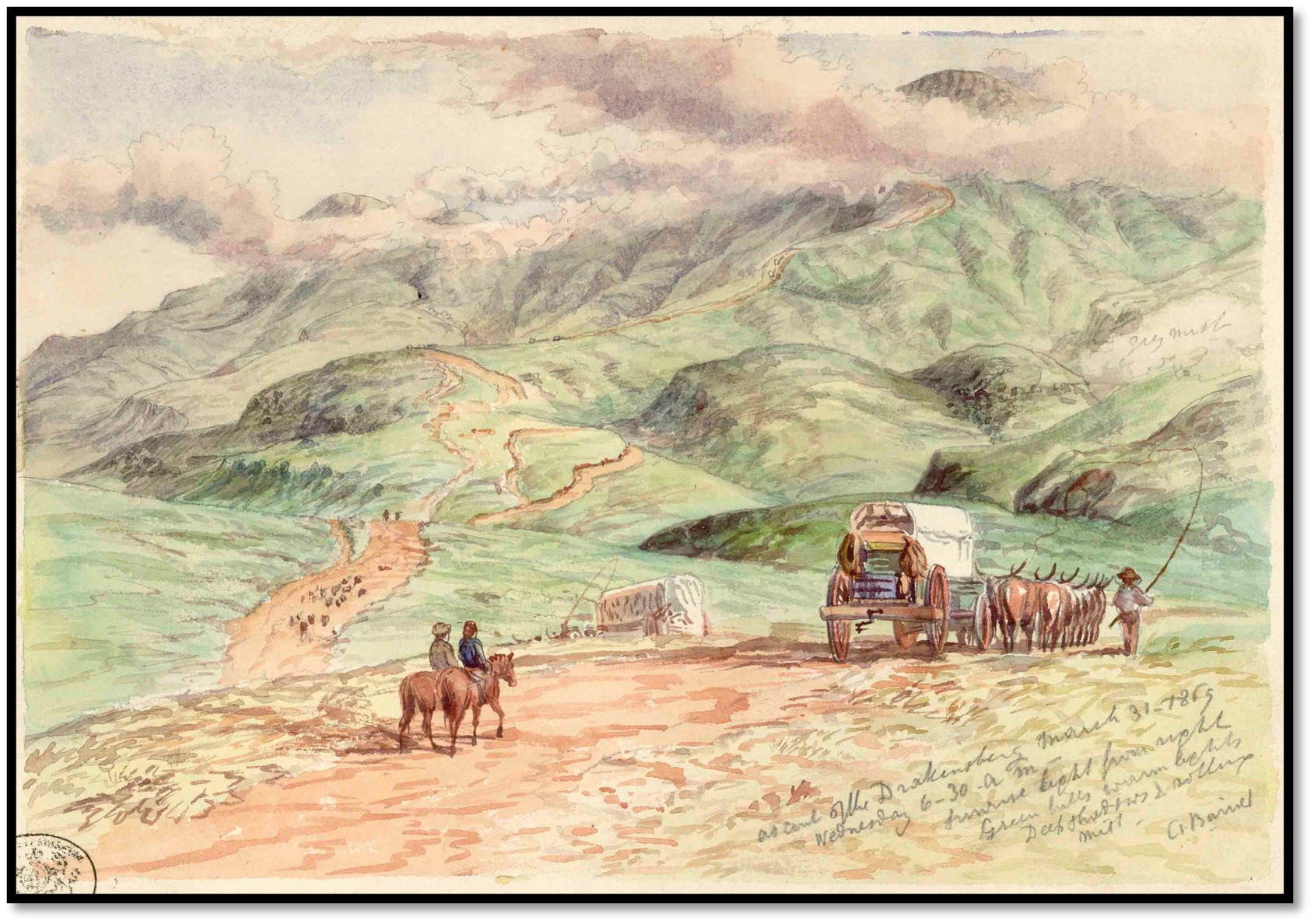

NHM (London) No 4: Thomas Baines, Ascent of the Drakensberg 31 March 1869

He stayed at Potchefstroom[iii] for six weeks, before joining a hunting party from Natal that was going into that part of Bechuanaland[iv] held by chief Sechele and his Bakwena. They left on 12 June, returning on 24 October 1865. However, on his return to Potchefstroom, “that of the eight horses which I left here, seven are dead and the eighth dying as fast as he can. Horse sickness was never known to commence so early. It is my poor luck. I am now left without one horse, so I shall have to write a pack ox.” He was “stony broke” and £500 in debt. His friends George Phillips[v] and James Gifford[vi] persuaded Leask to stay with them on a farm and then in May 1866 to accompany them into Matabeleland to rebuild his finances through elephant hunting and selling the ivory. Gifford lent him a gun and Phillips enough money to buy a salted horse. They left on 4 May 1866 with two wagons, Gifford, Leask, Phillips, Shrigley (Phillip’s driver) Smith and Wilkinson.[vii]

Leask’s first visit to Matabeleland and Mashonaland 4 May – 5 December 1866

At Shoshong, the residence of Sekhomi, chief of the Bamangwato tribe, he says there were seventeen wagons, six going to the Zambesi Valley, seven to Matabeleland. At the first outspan after Shoshong they were joined by the trader Edward Chapman,[viii] Clarke,[ix] Hans Hai[x] and the young hunter William Finaughty.[xi]

On 6 June they were on the Tati river, but Leask does not report any inhabitants. They travelled on at a leisurely pace as this was the first opportunity to do some hunting.

10 June. Heard the report of guns this forenoon and a little before sundown the hunters returned. They shot four elephants this morning.

11 June. All hands started this morning again in search of elephants. Poor elephants, what a curse to them are their tusks. But for their ivory they would be unmolested in their desert home. Today we number twenty-one men and fourteen horses, quite a small army…Two hours brought us to fresh spoor which we followed up all day, going as stealthily as an Indian on the war-path, but could not come up to the elephants. About an hour before sundown, we left the spoor and went to where the dead elephants lay, having sent our food and blankets there.

12 June. I omitted to mention yesterday that the natives found an elephant which had died about two miles from the others, thus making five killed.

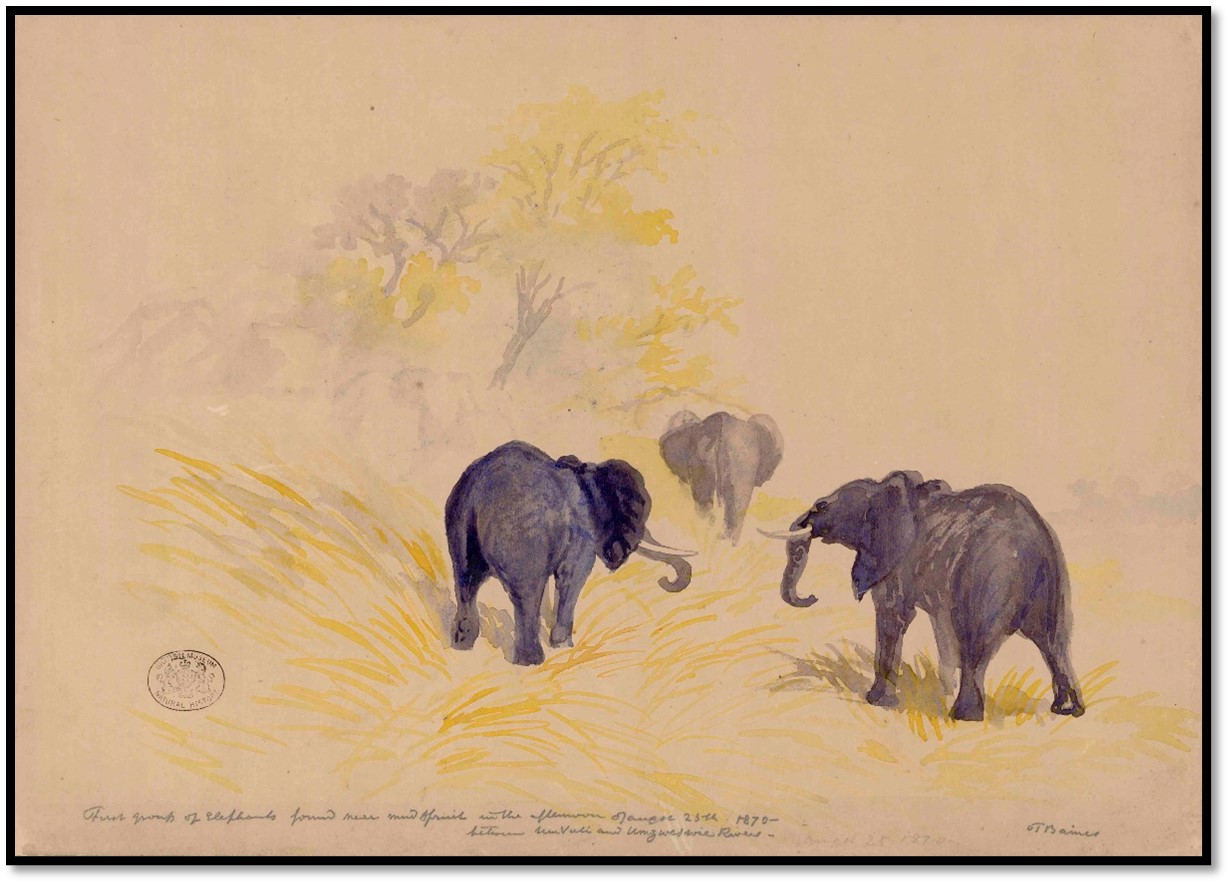

NHM (London) No 98; Thomas Baines, Elephant herd seen on 25 August 1870 between the Umfuli and Umsweswe rivers

13 June. Inspanned at 9am and had trekked about a mile when we found fresh elephant spoor across the road. Stopped the wagons and Gifford, Chapman, Finaughty, Clark, myself and three natives saddled up at once, taking four Makalaka to follow up the spoor. I cannot imagine how they managed to keep elephants spoor so well. For more than an hour I could see no indications of elephants, still, they kept on, and once or twice when they lost it among stones, they took a cast around and started off again. After three hours they came to a standstill and one of them said he saw something ahead. All eyes were turned to the spot pointed out but could distinguish nothing. Moved on again about a hundred yards when Chapman gave a low whistle and started off at a gallop. Everyone knew what was up, and it was the Devil take the hindmost, for the first one who puts a bullet into any game claims it, no matter how many help to kill it. We had gone about two hundred yards when Chapman jumped off and fired. Then for the first time, I saw an elephant in his wild state. What my feelings were I cannot describe, but I shall honestly admit that when the monster, after getting the bullet, gave a scream, stuck out his monstrous ears and came thundering towards us, I say, when I saw this, fear was my strong feeling and to turn and run my only thought. And not mine alone, for everyone gave way. He only came about twenty yards and turned.

We followed him, and in the thick bush, I lost sight of the elephant and his pursuers. Hearing a shot to the right, I went in that direction and soon came up to Finaughty, who was all alone with, in my opinion, a monstrous big bull. Seeing no other, I stuck to Finaughty. Certainly I could not help him much as, at the sight of the elephant, my horse got so excited that it took all my skill to manage him. He was not afraid, but awfully excited. After a little, I managed to quiet him somewhat and gave the elephant a shot behind the shoulder. Tried to give him another and my horse gave a start, and, big as the mark was, the bullet went wide of it. Finaughty all this time was loading and firing - it was his four to the pound rifle - as quickly as possible. I loaded again, no easy job on horseback when the animal is excited and was trying to have another shot when Finaughty shouted, ‘He’s coming! Look out!’ And sure enough, he was coming. And a more ugly animal than he looked then I never want to see. It was turn tail and run. He came about two hundred yards and stood, looking as black as thunder. When he stood, we stood. When he moved away, we followed him, firing all the time, as quickly as we could.

Matters went on in this style until he charged three times. Once, before running, I managed to give him a bullet somewhere about the head, but instead of stopping him, it seemed to have the contrary effect, for he gave us a long chase and we had to go very sharply to keep ahead. I looked over my shoulder to see if he was still coming and, through that, very nearly ran foul of a thorn tree. Finaughty’s bullets got done and, after the third charge, my horse gave me enough to do to keep my seat in the saddle. Consequently, I gave my rifle to Finaughty, his horse being comparatively quiet, though far from being a perfect shooting horse. Finaughty put seven drams of the best powder in my rifle - 14 to the pound, and gave the elephant six shots, after which he stood with his head toward us, seemingly knowing that we wanted to hit him behind the shoulder. He looked fearfully sulky as he stood eyeing us, shaking his ears and spouting water over himself. I kept a sharp look out to see if the coast was clear for a bolt, but the poor noble animal was done. Finaughty got off, crept around the bushes and gave him a good shot behind the shoulder. He gave one stagger and fell to rise no more. I must say I was sorry for his fall, though I had helped in killing him. He fought bravely and succumbed only at death.

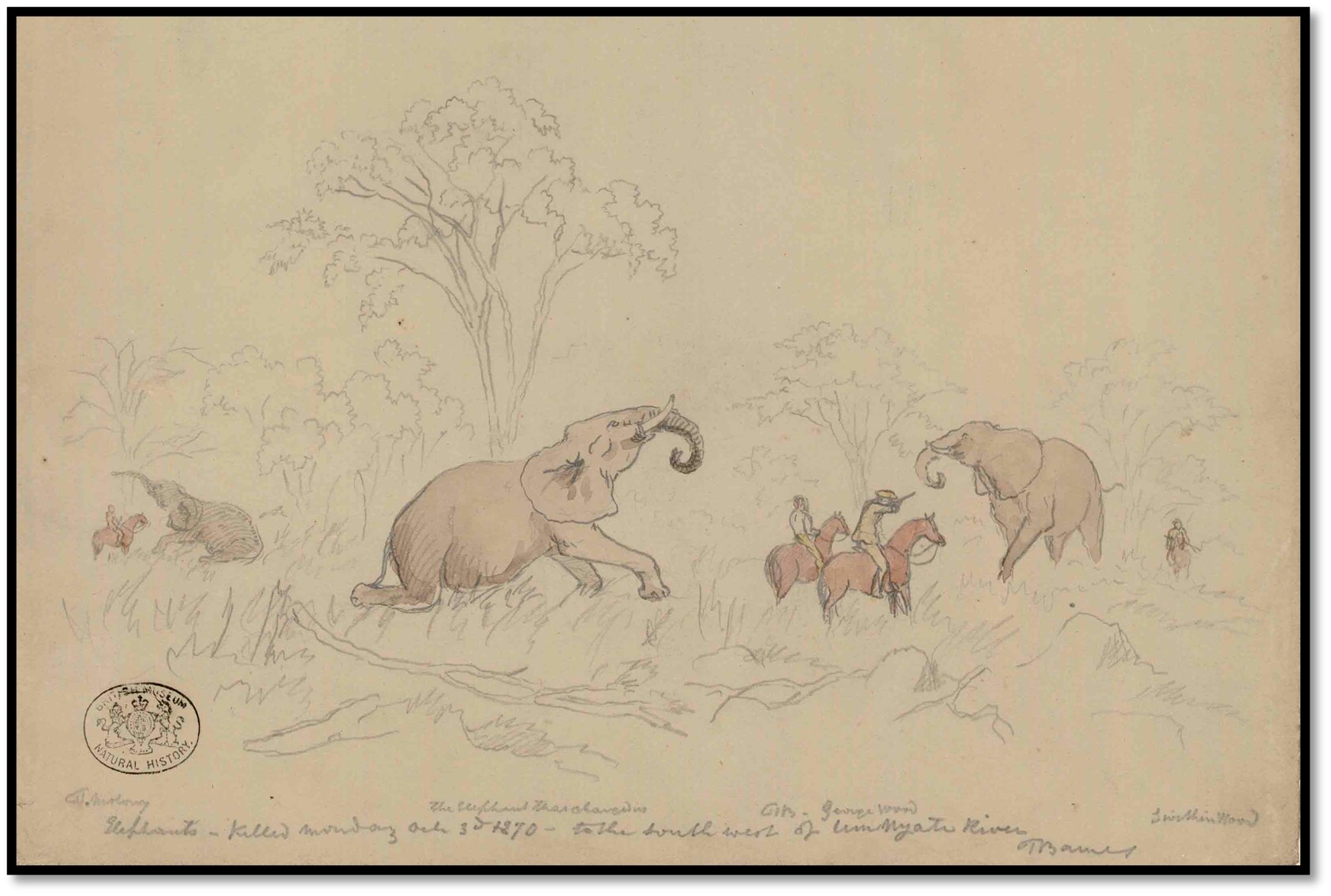

NHM (London) No 105: Thomas Baines, elephants killed 3 October 1870 by George and Swithin Wood south west of the Umniati (now Munyati) river

17 June. Manyami sent messengers to Mzilikazi this morning to inform him that we were here. We shall probably have to wait till the messengers return, which will be at least six days.

24 June. They reach the cattle outpost where Mzilikazi is camped. We all went to pay our devoirs to his majesty this morning. Found him seated in an armchair, an old Balmoral cap on his head, a dirty blanket around him and a tiger[xii] kaross, outside his hut. Since the death of his favourite wife[xiii] some three years before, the King, “a little, palsied, frail old man in his second childhood” has taken to a wandering way of life.

30 June. Went out for a hunt and Lobengula, one of the chief’s sons, joined. Chased a troop of thirty giraffe and turned a fat cow towards the wagons for about two miles. Unfortunately Leask’s horse took a route through a haak-thorn bush, “which caught me full in the face. Tried to stick on but came off. Got up as quickly as possible, but too late to catch my horse, which never looked at me, but went on after the giraffe, both of which were soon out of sight, and I was left, fearfully torn, scratched and full of thorns to pick up my rifle and cap and find my way to the wagons on foot as best I could. It must be some mismanagement on my part that brings me to grief so often.”

11 July. Started for Inyati about 9am, five wagons, twelve white men and twenty-four horses.

15 July. “Hartley keeps us in amusement in the evening by relating the most wonderful tales and adventures that ever befell any person. There are such a number of them, and they all happened to himself. I have often heard it said that he was fond of drawing the longbow and, from what I have heard him relate, I consider him the best hand at it that ever I met. We have tried to tell a few monstrous tales, with the idea of surpassing him, but it has been invariably a failure, he can beat us all by miles.

Today we passed an old cattle kraal; the dung must be at least six feet thick and over fifty yards in diameter.” The dung was burning and in the evening the topic of conversation was the time that they take to burn. Finaughty said he knew one in the Cape Colony that burned for seven years. Hartley pooh-poohed and said he knew one near Marico that burned for twenty-one years. “He said the one passed today was burning when he passed late last year and he thinks it will burn at least two years yet. Unfortunately, Inyoka (Snake) our guide, was with Hartley in the same capacity last year, and I asked him quietly how long the kraal had been burning. He said it could not be more than one moon, for he passed it about five weeks ago and it was not on fire then. Upon being asked whether it was not burning when Hartley was here last year, he laughed at me.”

25 July. They are camped at the Sebakwe river. “Viljoen[xiv] killed over hundred elephants before he got this far last year. The country is literally tramped up with the spoor left in the summer, but hitherto no sign of their having been here lately, except the spoor of three bulls, which we saw some distance below. They must have trekked to the fly.”

27 July. “By sunrise we were in the saddle with a most murderous determination to kill every unfortunate elephant we could find.” They rode east to the Mashaba range of hills, and found fresh elephant spoor, “At every step were fresh traces, trees broken and the bark peeled off, the dung still wet on the outside and the foot-prints quite fresh… They led us by a very roundabout way from one side of the mountain to the other, where we found them standing. My first thought was to leave them unmolested, as I considered it impossible to chase them and, worse still, to get away if chased by them. But all the experienced hunters started after them at a canter, so I was compelled to do the same….We followed the spoor, Old Chris[xv] leading, and came across one unfortunate small elephant, to which Old Chris gave the first shot and I the last, which was the only shot I fired. I was not at all plucky till I saw the elephant nearly done for. Then I came up in hot haste, as daring as ever a one among them, pulled up, let fly, hit the elephant - or something else - when down the poor animal fell. By this time the firing had ceased and we retraced our steps to where the others were last seen. In half an hour’s time, we were all together. The game killed was six elephants. Hartley, his two sons and Wilkinson three, Gifford one, Finaughty one, and old Chris, Thomas Maloney[xvi] and myself one. The tusks would make very good pipe stems. The elephants, though full grown - two of them had calves - were very small. Hartley, who knows everything, says they are ‘hill elephants.’ The Old Baas, who has seen more than nine-tenths of all the elephant hunters, shot more elephants than ever were by one man shot, says he never hunted in such a country as we were in today.”

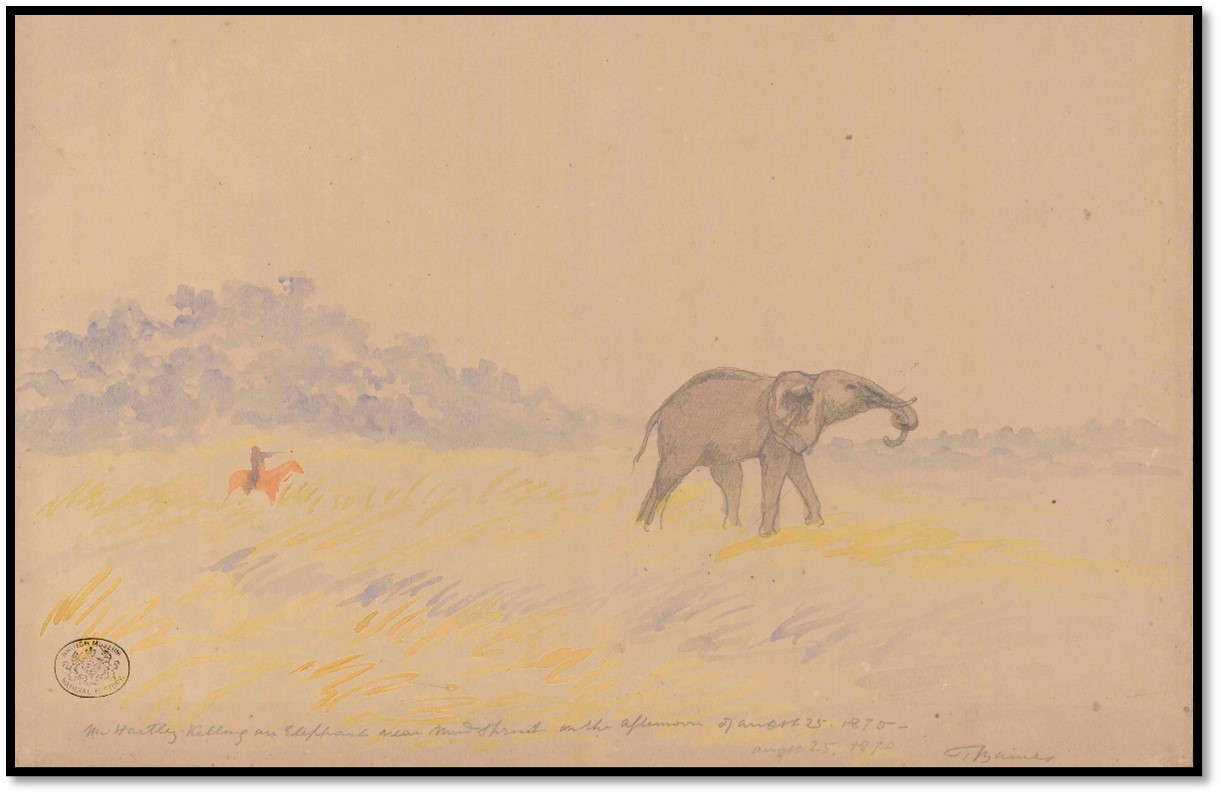

NHM (London) No 99: Thomas Baines, Henry Hartley killing an elephant near Mud Spruit (headwaters of the Chirundazi stream) on 25 August 1870

11 Aug. They are camped south of the Umfuli river. “…Rode north west about two hours; found fresh bull-elephant spoor… had scarcely turned to look for the spoor when we saw four elephants break cover and run straight across the valley for about five hundred yards below us. It was a grand sight to see the huge monsters, with their trunks turned up, tearing through the long grass, making straight for the bush. There was no time to pause and admire, however. It was one shout, ‘There they are!’ and every man dug the spurs in the horses’ flanks and went flying down the valley to get a sight before they got into the bush, heedless of long grass, stones or holes…

It sometimes happens in horse racing that the first horse does not win. And it was so in this. For I was ahead, rushed up to within forty yards, pulled up short, but before I could raise the gun to fire, my horse was round, like a top. Fred Hartley and Gifford fired nearly together. Fred Hartley about a second before Gifford. They both fired at the large bull which moved a few yards when his right hind leg gave way under him. The other elephants went into the bush, we after them, merely keeping them in sight until they got into better country. When I got up to the elephants again, three were hit, the fourth not visible…

I had passed Gifford and left him loading so as soon as he came up, I showed him his elephant and went off to the other. Gave him two shots behind the shoulder and was loading again, going on at a slow canter to keep him in sight, while watching through the bush, when I dropped my ramrod; instead of putting it in the pipe, I slipped it past. Jumped off to pick it up, saw the elephant then and never after, for when I got up again, he was out of sight and I could not find him…

Having given up the search and hearing some shots to the right, I went in that direction and found Gifford with his elephant, so I consoled myself the loss of mine by helping him to kill his… I was a yard or two in the rear, loading, and was in the act of ramming down my bullet when someone shouted, ‘Look out, he's coming!’ and coming he was, trumpeting like thunder. I grasped the gun and reins in one hand and the ramrod in the other, and sloped through the bushes pretty sharp, straight ahead about a hundred yards and pulled up. Looked about in every direction, but could not see Gifford, nor the elephant. Went in the direction in which they were last seen and came across them. In the charge Gifford had been unhorsed by a tree, and the elephant stood within a few yards of him, fortunately without seeing him or smelling him. Gifford lay as still as a stone until the beast turned, when he sprang up, made a bound to his horse, which was, Rosinante-like,[xvii] standing quite still within a few yards of his master. Gave the elephant a few good shots, he went into the thick bush, stood still a few minutes and fell dead…

Fred Hartley, Old Chris and Old Baas had killed four bulls and seen five or six more. This provoked me considerably, as we had killed only one.”

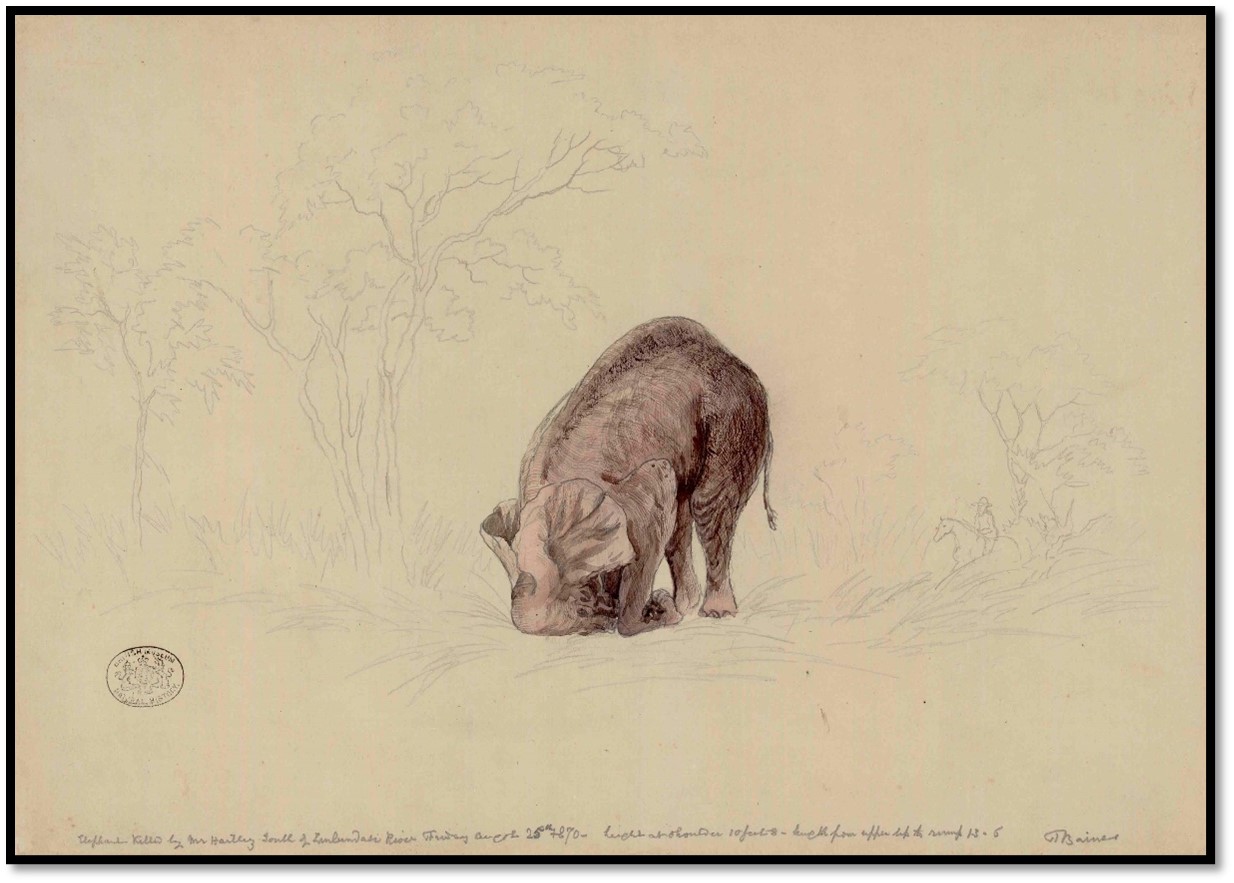

NHM (London) No 100: Thomas Baines, Elephant killed by henry Hartley south of the Chirundazi river on 25 August 1870

17 August. “Mauch,[xviii] who went out yesterday on a sort of exploring expedition, came upon five lions which got up in front of him. He wanted to get to a particular hill; the lions were between him and it and, as they did not seem inclined to retreat to any distance, he merely waited till they moved a little, when he returned and mounted the first tree. He slept none that night but rested in a mopane tree.

Hartley returned about midday, having attained the height of ill-temper. Frank,[xix] Old Klaas[xx] and Jacob[xxi] started for the ‘fly’ vowing death on all the elephants to be found.”

20 August. Camping between the Umfuli (Mupfure) and Panyama (Hunyani, Manyame) rivers. “Up-saddled at sunrise, turned eastward, then south and were homeward bound when we found fresh spoor. Followed it about two miles, when we came upon the elephants, about thirty in number. They were feeding very quietly and never saw us until a shower of bullets woke them up. Went in chase of the biggest I could get at. Fearing that some other person might take a fancy to him - for an elephant hunting it is every man for himself and first shot has it - gave a tug at the reins, raised the gun and fired at random, as my horse did not feel disposed to stand. Hit the elephant, however. After running about a quarter of a mile, he turned out from the others. Gave him another bullet which, more by good luck than good management, hit him behind the shoulder. When the elephant turned and chased, I sloped through the bushes and, in so doing, broke one of my stirrup leathers. Examined the damages; found the buckle hole torn out, put the buckle in the hole above and started in chase. The country being open, the elephant saw me before I could give him a shot, turned and chased me again, which excited my horse so that he would not stand. It was snap shooting. Had to hold the horse all the time and the beast, by tugging at the reins, sent some bullets over him and some under him. The elephant got one shot in the leg, which brought him on his backside, but did not break the bone. He got up, turned round and looked in astonishment, but did not charge, though I was standing about forty yards from him in open country.

Kept on loading and firing until I had exhausted one pouch full of bullets and, when I wanted to begin at my other pouch, found it empty. It had got unbuttoned and the bullets were gone. By this time, I could count fourteen bullets in the elephant, four just behind the shoulder. The animal was moving about very slowly and seemed rather sick. Hoping that he would die, or that some of the other hunters would come my way, I followed him up and fired blank shots at him by way of signal to the others. He walked about some time, then stood under a tree, walked on again, stood again, and then he went on again about two hours, till I left him, to try and find the other hunters and return to the elephant. Fired the last charge of powder; got bewildered and, lest I should get lost entirely, struck out for the wagons in a very bad temper. Arrived at the wagons two hours after sundown, hungry, tired and as cross as two sticks. The elephant charged me six times. Got at least fourteen bullets, and then I came away and left him standing! Add to this the value of his tasks at least £20 to £25. My misfortunes as a hunter would make an amusing tale.”

30 August. “Old Baas, Wilkinson, Thomas Maloney and myself lost the others.[xxii] We found fresh spoor and did our best to keep it but failed and had to come to a standstill when a Mashona that had kept with us said he heard trees breaking to the left. Started off in that direction and found spoor of elephants running. Cantered on it; lost it among the stones. Old Baas turned to the left to look for it and we to the right. Found six elephants on the top of the small hill. They ran towards the most inaccessible parts. I got after one which turned to the right and could scarcely keep up with him. The end of it was the elephant got in a place where I could not canter. The bush was thick, the hill covered with stones and full of holes. My horse would not stand a second to let me shoot. If I dropped the reins he turned round; hold them slack and he went straight on; hold them lightly and he ran back. Get off I dare not, for the chances were he would not let me get on his back again. So after firing five shots without being able to see the after-sight, three of which missed the elephant altogether, I lost sight of the elephant in very thick bush and would not go in search of him. His tasks would have made pipe stems.

…Heard some shots in the distance, turned towards them and got up just in time to hear the last scream of a young bull which Gifford, Finaughty and Fred Hartley had managed to murder with something like twenty-seven bullets. He charged twice and kept in very bad country. Gifford wounded a young bull severely and lost sight of him. The Old Baas came up from another direction, having got into decent country and killed a cow. Old Chris returned, having pursued the elephants over another hill and shot nothing. So out of three distinct lots which were seen, two were killed! So much for finding elephants in stony hills.”

1 September. Out again next morning in search of elephant. crossed Umgesi and went along the west side of the mountain range. Came upon the elephants in thick bush on a hillside. Fortunately we were above them. Tried to drive them out of the hills; they turned behind us, came across the natives and charged them. The natives screamed, shouted and whistled, and succeeded in turning them, so that, with the natives on one hand and us on the other, we got them out of the hills into fine open country. There we drove and harried them about, shooting as fast as possible. It was hard work for men and horses. My horse got very much excited and, as he would not allow me to shoot, I did more in the driving and turning line, until my mouth was as dry as a cinder with shouting; I could not spit over my beard. We tumbled down eleven elephants and let one toothless cow and a calf go on their course.”

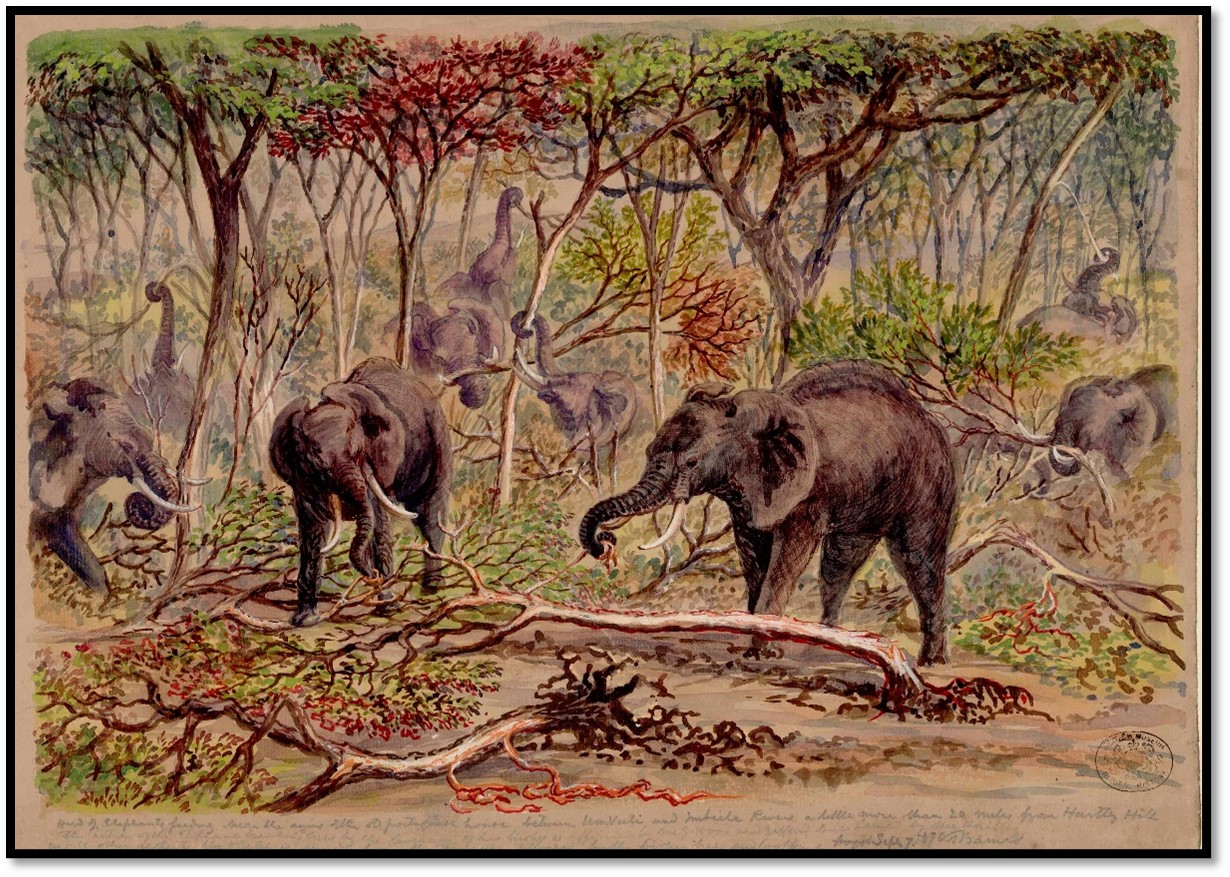

NHM (London) No 102: Thomas Baines, herd of elephants feeding between the Umfuli and Imbila rivers on 7 September 1870

29 September. “Arrived at Inyati (now Inyathi) the mission station at midday. Found the missionaries and their families quite well and heard all the news from them, viz. There had been no white people at the chief’s. The old man had been sick[xxiii]…”

3 October…”We go to see the chief almost every morning and generally find him sitting in the goat-kraal, no matter how wet it may be. His wives carry him in the chair, set him down in the midst of mud and water, put a tiger-skin under his feet, kindle a fire in front of him and then squat down by his side. All his attendants must sit in the dung and water; his white visitors are allowed to bring their stools. After he gets tired of sitting and drinking joala (beer) in the goat-kraal, he is put into the wagon, which business the women manage by hoisting him up in a blanket…”

15 November. “When we went to court this morning - held as usual in the goat kraal which, owing to the heavy rain last night, was knee-deep in matter about the consistency of gruel. At one side it was a little thicker, and there sat his royal highness, in his old arm-chair, the tiger-skin under his feet and a fire in front of him. There were two iron pots steaming by the fire, one containing water and some roots, etc. The other was under the special superintendence of an old charm doctor who was pulling all manner of roots, wood, etc. grinding them into a powder between two stones and putting it into the pot. A black bull and a black ram were killed and parts cut off all their extremities and put into the pot. All was then burnt to a powder to be used in doctoring the Army, a sort of sin-purifying sprinkling I suppose. The other pot was cared for by the women and was to give the King a vapour bath. They took the pot, placed it between the King's feet and then covered him over, head and all, with blankets. The old man endured it a little until he nearly suffocated; then he struggled till he got his head out, when he coughed and sneezed at a terrible rate. Whenever the King sneezes, all his attendants call out, ‘King, Big King! Above all men! Black Bull! Kumalo! etc.’

The doctoring done, beer was brought, then meat roasted on the grid-iron and the King had his breakfast, which he shared very freely with his visitors. Having fortified the inner man, he was lifted up in the chair by four flabby wives, carried to the wagon, lifted up in a blanket and went to sleep. When the King is not eating or sleeping or snuffing, he is drinking beer, which is held to his mouth by one of the favoured wives.”

References

J.P.R. Wallis (Editor) The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask 1865-1870. Central African Archives, Oppenheimer Series No 8, Chatto and Windus, London 1954

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd, Cape Town 1966

Notes

[i] Basutoland gained independence from the United Kingdom on 4 October 1966 and was renamed the Kingdom of Lesotho

[ii] Potchefstroom was also called Mooi River Dorp at the time

[iii] Of Potchefstroom he say. “A goodly number of the inhabitants are English and Europeans and these are not always on the best terms with the Boer population, which gives rise to hostile feelings, ending sometimes in rows and party fights. not very honourable to either party. The market square has been the scene of more than one yokeskei-and-knobkerrie battle ending in broken heads and disfigured visages.”

[iv] Bechuanaland, formerly the Bechuanaland Protectorate, gained independence on 30 September 1966 and was renamed the Republic of Botswana

[v] George ‘Elephant’ Phillips arrived in Natal in 1862, the same year as Thomas Leask. His trip to Matabeleland with Leask and Gifford was his first, he remained in the country and in 1865-6 travelled to the south-he Mazoe river in east hunting in the Fort Victoria district (now Masvingo) and although he rescued Karl Mauch and Paul Jebe, he did not see Great Zimbabwe. He accompanied Henry Hartley to Mashonaland in 1867 and in 1867/8 formed a partnership with George Westbeech at Pandamatenga that lasted until the latter’s death in 1888. He made several trips to Pandamatenga. In 1868 Phillips and Westbeech accompanied an amaNdebele raiding party into chief Hwata’s territory around the Mazoe river in Mashonaland. Mzilikazi died in 1888 and when Phillips brought a letter back from the Natal Governor stating Nkulumane was in Natal, he was arrested for a fortnight. Phillips and Westbeech were at Lobengula’s inauguration at Umhlahlanhlela on 22-24 January 1870. He was trusted by Mzilikazi and Lobengula becoming one of the old-timers in Matabeleland and hunted elephant and traded in Bulawayo. He witnessed the Wood-Chapman-Francis concession at Bulawayo. Left Matabeleland in 1890 after lived almost continuously in Matabeleland for 25 years.

[vi] James Gifford hunted and traded in Zululand before guiding the Glyn party to the Victoria Falls in 1863. Visited Mashonaland in 1866 with Leask, Phillips and the Hartley party, thereafter hunted many times with the Finaughty brothers, Henry Hartley and the Jennings family in Mashonaland. Stopped hunting after 1870 “the fever year” when so many died in Mashonaland and when the elephants retreated into the tsetse-fly country. (i.e. hunters could no longer hunt on horseback)

[vii] Fenwick Wilkinson named ‘Cap’ because he held the rank of Captain in a colonial regiment who accompanied the Hartley party in 1866

[viii] Edward Chapman was a trader originally based in Grahamstown and travelled annually to Matabeleland by 1860 - 66. He knew John Moffat at Inyati and in 1862 bought ivory and ostrich feathers from T.M. Thomas. He travelled with Finaughty in 1864 and bought over 5,000 lbs of ivory. He quit interior trading after 1866 and kept a large store at Kuruman. He formed a syndicate with G. Wood and W.C. Francis and they obtained a mineral concession on 11 November 1887 for the land between the Shashe and Macloutsie rivers from Lobengula, but the land ownership was disputed by Khama III. Chapman and Francis were at Lobengula’s in 1888 when Charles Rudd was present and obtained the Rudd Concession.

[ix] Richard Clarke in 1866 traded with Chapman, whilst Finaughty went hunting. Back in 1867 he bought ivory from T.M. Thomas at Inyati. Established the firm of Francis and Clarke in Shoshong during 1872 – 87.

[x] Hans Hai had long hunted in Matabeleland and is mentioned by Robert Moffat. He came from Waterboer’s country, a 100 miles west of Bloemfontein

[xi] William Finaughty (1843 – 1917) aged 22 years old made his first journey in 1865 to Matabeleland and killed his first elephant and lion. In 1866 he hunted on halves with Henry Hartley, but his success made the Hartley party jealous and they parted. He traded with Chapman at Shoshong and hunted with Napier on the Tati and Shashe rivers and then into Mashonaland in 1868. Often referred to as ‘Old Bill’ he was one of the most successful mounted elephant hunters killing around 500 elephants in his career. See the article William Finaughty (1843 – 1917) one of the great elephant hunters who knew both Mzilikazi and Lobengula and brought the two ship’s cannon now at the Natural History Museum in Bulawayo under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xii] Leopards were usually referred to as tigers at the time

[xiii] The favourite wife was uLoziba, John Moffat wrote at the time, “about the middle of October the chief wife of our king died at Nyati. She was the mother of the town, and immediately the court removed, first to camp life for some weeks on the river, and thence to towns where [Mzilikazi] always tarries this season.” uLoziba was buried a short distance north east of Nyati.

[xiv] Jan Willem Viljoen. By 1851 when Viljoen accompanied Piet Jacobs to Lake Ngami he was an experienced hunter. He accompanied James Chapman into the interior in 1852. Between 1862 – 4 he has Mzilikazi’s permission to hunt between the Ntwetwe and Makarikari pans and in 1865 hunted in Mashonaland, in 1866 in the Zambesi Valley. Viljoen acted as President Pretorius’ emissary and became unpopular with the native chiefs. In 1872 he hunted once again in Mashonaland with Lobengula’s permission, and in the following years 1873 – 1879 hunted on the Semokwe river in southern Matabeleland. In his last season in 1878 he hunted at the Ngwenya river but were defeated by tsetse-fly. Leask P78 writes that Viljoen lost over 40 oxen with Inyoka saying his guides took him intentionally into the ‘fly’ because they hate all Boers. One of the greatest hunters, he had several close calls with elephant and lion. Liked for his courteousness and help for all, died in the Marico district in 1891

[xv] Christiaan Harmse ‘Old Chris’ hunted with the Hartley party in 1866 and 1867 but stayed on to hunt in the rainy season and caught fever. Old Chris, his three daughters and three servants all died. Mrs Harmse, their small son ans one servant survived and Mrs Harmse managed to get the wagon to the Umfuli (now Mupfure) river where they were rescued in August 1868 by Finaughty and Napier.

[xvi] Thomas Maloney was Hartley’s son-in-law and accompanied the Hartley party in 1866 – 1870, stopped hunting after 1870.

[xvii] Don Quixote renamed his horse as well as his own (his original name was Alonso Quixano) in order to start a new life as chivalrous night. He chose Rosinante for his horse because it seemed ‘lofty, sonorous and significant.’

[xviii] Karl Mauch, secretly searching at Hartley’s invitation for gold, the amaNdebele thought he was mad. See the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xix] Frank was probably a wagon-driver

[xx] Old Glass or Old Klaas, appears to have been a Hottentot, now referred to as Khoekhoe or Khoikhoi hunter.

[xxi] Piet Jacobs born circa 1800, amongst the first Boers with Viljoen and Swartz to hunt at Lake Ngami from 1851 - 1860 hunted between the Botletle and Chobe rivers. In 1865 Mzilikazi permitted them to hunt to the Umfuli river. They killed 100 before the Sebakwe river, 190 in total, 47 in one day and took back about 10,000 lbs of ivory. However they sold five guns to the Mashona and Mzilikazi barred them from the country for some years

[xxii] They are in Ngezi river area

[xxiii] Mzilikazi was poorly for a long time and died on 9 September 1868

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: