Zimbabwe’s illicit Gold Market hinders the country’s development

Background

Almost all the information below is sourced from the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) in an article called Illicit Gold Markets in East and Southern Africa that was issued in May 2021.

This is a very comprehensive and in-depth article on the illicit gold markets in South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Zimbabwe with comments on South Africa. Although there are many similarities between these countries I will concentrate on Zimbabwe as most relevant to the readers of this website.

Overview

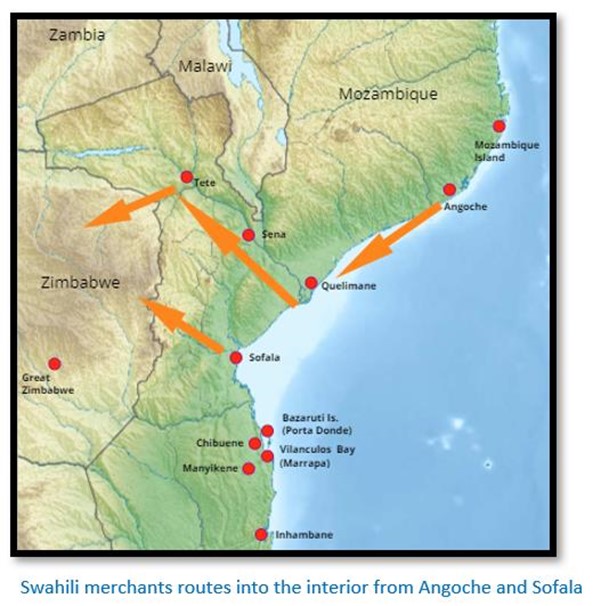

Most Zimbabweans will know that gold has played an important part in the life of the country from at least the 7th century when Swahili gold traders came from the Kilwa Sultanate and entered Zimbabwe from Quelimane and Angoche via the Zambesi river and from Sofala (south of present-day Beira) via the Buzi river. There are a number of articles on this website that refer to this subject.

The GI-TOC report states that over time the gold markets have evolved with the entry of new actors (in Zimbabwe pre-European gold mining came to a standstill with the arrival of the 1890 Pioneer Column) the influence of international markets (in Zimbabwe the entry of Chinese gold miners) and changing regulatory regimes – both domestic and foreign.

The report states: “Today, the artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) sector is governed by increasingly comprehensive legal and regulatory frameworks and is reliant on transnational supply chains that connect rural mining operations to international gold hubs.”

Illicit activities in Zimbabwe have undermined the potential for gold to be a catalyst for development

Although I refer to only Zimbabwe, the report concludes that most of the countries in the study have suffered the same fate. The gold trade has drawn many criminal actors owing to:

- its high-return, low-risk nature - especially when compared to the trade in other commodities, both licit and illicit

- the advantages of gold as a commodity - such as anonymity, ease of movement and global exchangeability.

The report states that the above factors: “attract illicit actors to the gold sector, who then exploit vulnerabilities in the system. Criminal and corrupt actors will use corruption and violence, as well as financial levers to profit from and control the trade.”

Informal mining operators struggle to comply with regulatory demands

- a significant issue that fuels illicit gold markets is access to land and mineral rights

- regulatory frameworks can make it difficult for small operators to legally mine gold deposits, creating the conditions for illicit gold markets to form

- without clear, up-to-date and functional land ownership conditions that define property rights over mineral deposits, violence and corruption become the tools for controlling extraction.

In Zimbabwe the political elite have access through the ZANU-PF government infrastructure securing land access and mining licences, often through corruption or by force. This is facilitated through mismanagement within the relevant mining ministries and artisanal and small workers have little ability to legalise their mining claims. “In Zimbabwe mining disputes occur when multiple mining titles are being granted for the same location, which has led to conflict and chaos.”

Where political actors do not obtain a mining licence, they take over mining operations using deception, political pressure and violence.

The problem is maximising gold’s potential for development in Zimbabwe whilst seeking to minimise the criminality associated with ASGM’s

In Zimbabwe’s situation artisanal miners have become increasingly reliant on criminal actors who aggressively seek to maximize profits from illicit gold markets. Usually they are in positions of power, especially state actors such as government officials and ZANU PF politicians, taking advantage of obscurity to seize and compete for mineral wealth.

The GI-TOC report seeks to “unpack the factors that shape and drive the East and Southern African gold markets…South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya and Zimbabwe were selected for field research, with some limited research conducted in South Africa.”

Why was Zimbabwe included in the study?

South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya and Zimbabwe were selected: “because they are gold producers, possess known illicit gold markets and have significant interlinked supply chains and market structures.” Tanzania, Mozambique and Madagascar might also have been included in the report but were excluded because of time and resource constraints.

Methodology

Country-level investigators: “were charged with collecting data (quantitative and qualitative) on supply chains, local market structures and gold pricing along supply chains. In addition, semi-structured interviews with a wide range of stakeholders, including miners, buyers, journalists and civil society organizations, were conducted. The report is largely informed by interviews with people operating in or linked to the illicit gold sector, which have been triangulated with other sources and trade data where available.”

Areas of particular interest for the investigators were asked to examine:

- Supply chains: The direction of gold flows and the various actors involved at different points in the supply chain were examined. This included identifying the means by which gold is moved from mine sites to transit hubs and from the continent to offshore markets.

- Market structures: Investigators were asked to build a profile of prominent and influential actors in gold markets, including political actors, foreign nationals and armed groups. This line of investigation aimed to identify core structural components of illicit gold markets in the region, with particular attention to those features that enable illicit trade to emerge and flourish, as well as factors that disrupt these markets. It examined which actors benefit the most if corruption or violence is used to control the gold trade, and what benefits accrue to local communities.”

Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) differs between countries

There is wide variation in the type of ASGM although it is often characterised a being ‘low capital intensive and using highly labour-intensive technology.’

However there are wide variations.

In South Sudan, gold mining and processing techniques employed by artisanal miners are more rudimentary than seen elsewhere, with miners lacking even the most basic equipment. For example, no mechanization or chemicals (including mercury) is used to process artisanal mined gold.

In contrast, mining operations in parts of Kenya and Zimbabwe are very developed, with hundreds of people present at some sites, using highly mechanized processes including stamp mills and rock crushers.

Small-scale mining in South Africa is different from what is seen elsewhere on the continent. Most miners (called Zama Zamas after a Zulu term meaning ‘those that try to get something from nothing’) infiltrate and work illegally in abandoned and active commercial large-scale mine shafts.

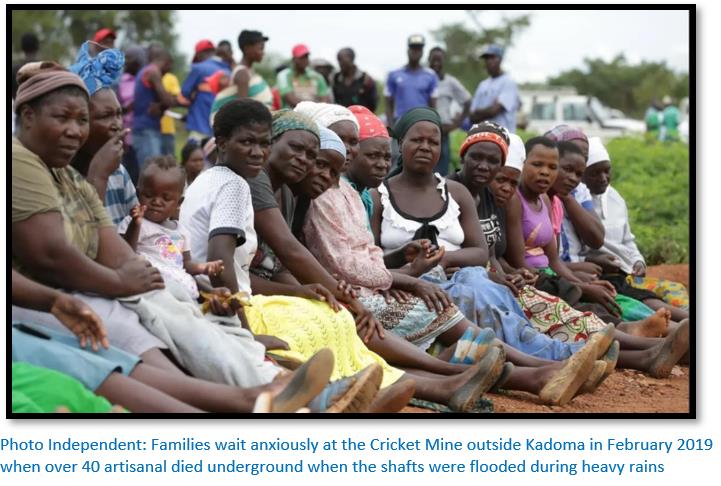

ASGM is always a dangerous activity

This is because almost all ASGM mining sites lack the appropriate equipment and safety measures. For example, around Kapoeta in South Sudan, trench collapses can kill up to four people a month. Likewise, 29 miners were killed in Zimbabwe in 2019 when shafts were flooded leaving miners trapped underground. More than 300 artisanal gold miners in South Africa were reported dead between 2012 and 2015 as a result of collapsing tunnels, though the Zama Zamas[i] maintain this number is vastly under-representative.[ii]

Use of mercury at ASGM sites is a major health issue

The wide-spread use of mercury is dangerous to human health as it enters the human food chain and to the environment but the illicit mercury trade and the illicit gold trade go hand-in-hand. In Zimbabwe, this market is driven by a WhatsApp group for miners, where mercury is openly advertised and sold by mining sponsors, including gold buyers.

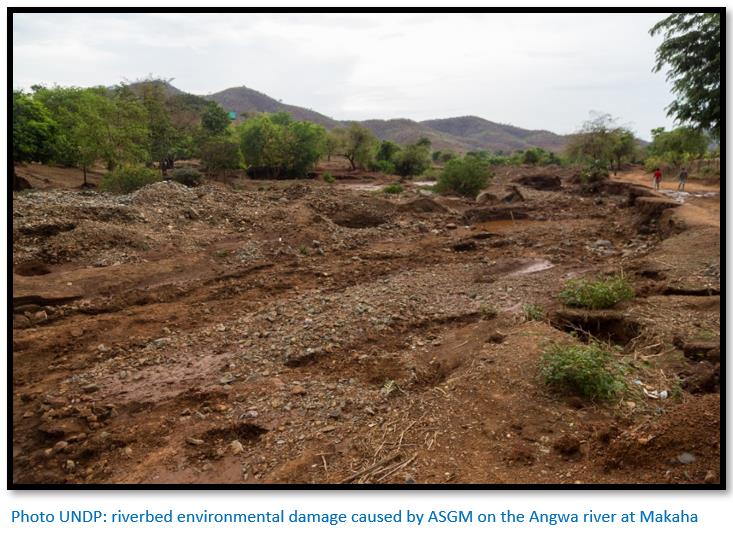

Environmental damage caused by ASGM is severe

The report cites foreign actors, who operate illegally or in collaboration with corrupt government officials, that often introduce new techniques or technology that amplify negative environmental impacts. In Zimbabwe the government is allowing mining in protected areas, such as the Matobo and Umfurudzi National Parks and on the Mutare, Mazowe and Angwa rivers.

For example, Bulawayo 24News had an article[iii] that mining companies with foreign ownership - particularly from China and Belarus, in collaboration with politically important locals are using heavy machinery to mine for gold on river banks under the guise that they are desilting the watercourses.

Wellington Takavarasha, CEO of the Zimbabwe Small-Scale Miners Federation was quoted as saying: "Initially, the granting of licences was done to desilt the rivers and in the process, mine gold." However Bulawayo24’s reporter found that a company called Tres Balla Syndicate was using heavy earthmoving equipment on Mazowe River, an illegal gold panning hotspot. The reporter was told the mining operation was owned by Colonel Obert Bastion Guvheya, the brother of Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga who officially uses Guvheya as one of his names and that Guvheya was in a partnership with the state-owned Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC).

The GI-TOC also reported that in Zimbabwe corruption and criminality have increased the speed and severity of the environmental damage caused by ASGM. The Zimbabwe government lifted a ban on riverbed mining, a practice with detrimental environmental consequences and mining operators can conduct riverbed mining in partnership with the state-owned Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC)

In theory, this partnership promotes strong environmental management practices and regulatory checks. However, in practice, it is alleged that the arrangement allows senior politicians and military chiefs to parcel out lucrative riverbed permits to foreign investors for a fee without proper environmental protections being put in place.

The illicit goldmining supply chain

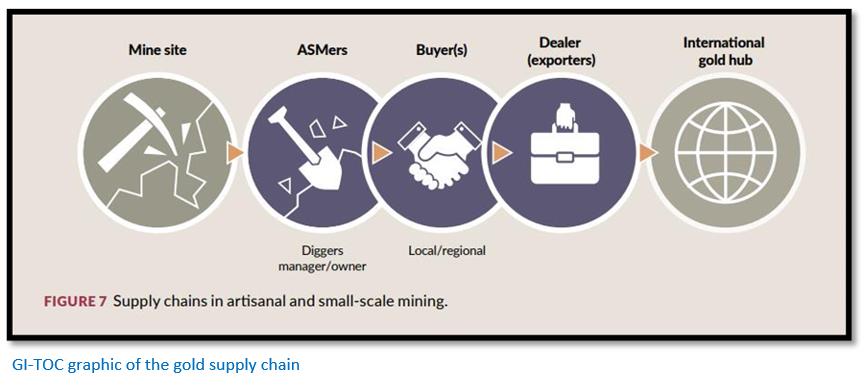

The report splits the participants as follows:

- Miners: popularly known as makorokoza. While the description is often applied to all individuals working at a mine site, there is a wide variety of roles, hierarchies and other factors that differentiate members of this group. Diggers, who extract gold-bearing ore, will often work for a mine manager or pit owner. Given the informal nature of ASGM, often the owner has financed the operation but does not hold formal mining rights or a licence. Miners can also include washers. Often women are washers, who wash gold bearing ore with water as a first step to extracting gold.

The report states: “that ASGM is an important economic shock absorber in countries such as Zimbabwe facing growing poverty, high levels of unemployment and declining agricultural production…Despite the often unsafe and sometimes exploitative conditions, many Africans are drawn to the business by favourable economic returns, even for those on the lowest rung of the ASGM ladder, and the fact it provides them with a livelihood in an environment that offers few other options.”

- Buyers: “Local buyers who buy at or close to mine sites tend to be natives of the area, especially in areas that are difficult to access or require local knowledge and connections to do business. They will then sell gold to bigger buyers or dealers in national or regional trade hubs. There is no set number of buyers in supply chains, although it is often limited to one or two intermediaries. Their role and relationships with others in the supply chain can vary significantly. For example, a miner may also be a buyer, or a buyer may be an independent actor or an agent for a dealer. Depending on their arrangement, buyers may hold both roles at once, buying some gold as an agent and some as an independent buyer.”

Political elites are also reported to force miners and local buyers to sell gold to buyers or companies that they control and may punish miners who sell elsewhere. As a result, many gold miners and buyers operate in secret.

“Major foreign buyers, often from South Africa, as well as Indians and actors from Dubai, tend to partner with licensed Zimbabwean dealers to buy large quantities of gold on the illicit market. They sponsor gold buyers in Harare, providing pre-financing of up to US$1 million for gold purchases. Zimbabwean nationals provide a front for the operations, hiding their involvement.”

- Dealers: “Dealers are major players and the largest buyers in the African gold supply chain. They are mostly stationed in national or regional export hubs,” such as Bulawayo or Harare and organise the export-smuggling of gold from Zimbabwe to refineries in South Africa or directly to the gold markets of Dubai.

The criminality increases down the supply chain

The report notes the difficulty of distinguishing between informality and criminality within the gold mining sector. Upstream, at or close to the mine site, activity is often best characterised as informal.

“However, as gold moves downstream, the criminal culpability of actors tends to increase, with major dealers knowingly engaging in illicit activity. As a result, ASGM markets are not only a pyramid, consolidating as they move down the supply chain, but also a gradient, reflecting the increasing sophistication and criminality of actors through the supply chain. Criminal control is often hidden behind a diffuse web of supply chains, financial flows and intermediaries. Although the networks are ‘loose’ this does not mean they are not well entrenched or well controlled.”

These criminal networks in Zimbabwe: “tend to be transactional, driven and controlled by a limited number of individuals at key points in the chain. Influential criminal and corrupt actors often disguise their involvement behind front companies and representatives or geographically dispersed networks of intermediaries.”

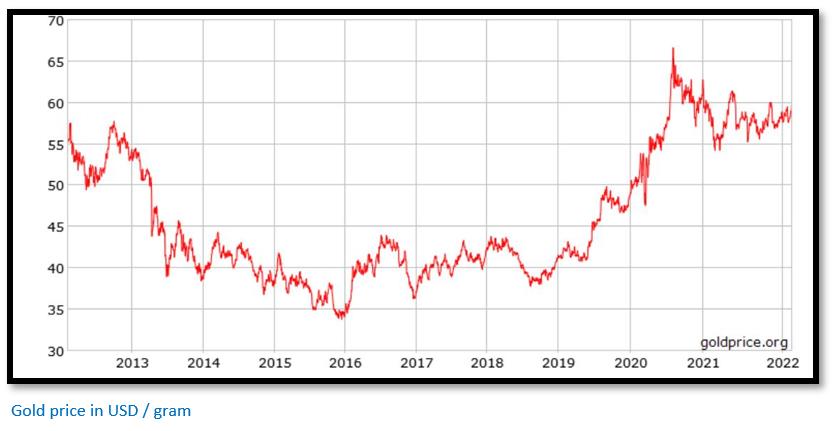

Gold prices

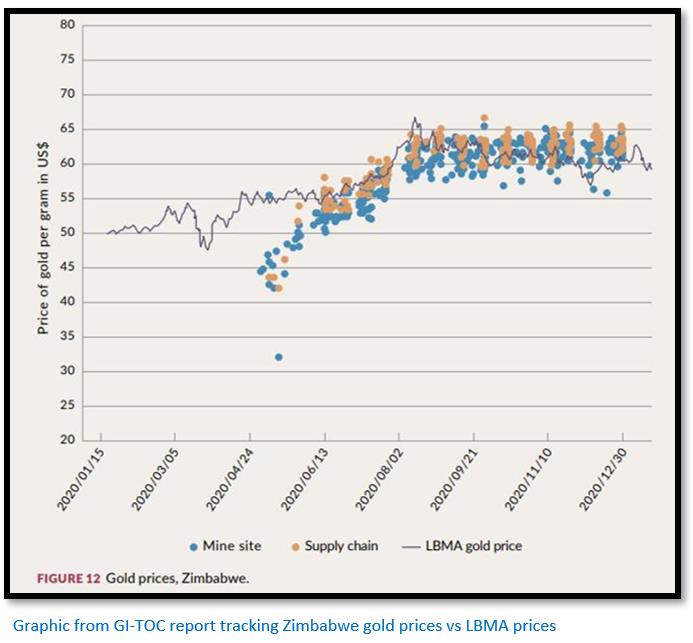

The London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) gold price is used as the benchmark influencing prices all the way to mine sites in Africa. The LBMA price is set in US dollars per troy ounce, based on a gold purity of 99.99 per cent and in August 2020 hit an all-time high of US$66.55 per gram.

The report states mine site gold prices ranging from 83% - 95% of the LBMA gold price, in some cases, miners may receive only 50% - 60% of the LBMA gold price, but these rates tend to be associated with conflict actors who violently control territory and supply chains.

In Zimbabwe both miners and local buyers know the current gold price with the result that: “gold prices at mine sites in Zimbabwe are high for the region, with little variation between the prices offered at mine sites and those offered by downstream buyers...as a result, profit margins tend to be small, just US$1 to US$3 per gram at transaction points in the supply chain.” In other countries such as South Sudan with less knowledge of international prices and purity assessments by miners, prices tend to be lower.

In Zimbabwe and South Sudan their volatile currency exchange rates also influence prices and often there is a mismatch between the official exchange rate and more favourable rates offered on the black market. The result is that gold miners and traders often prefer to use the black-market rate to calculate gold prices.

Once the gold is exported from Africa, dealers can sell it at or close to LBMA rates, with about 99% of the value in international gold hubs such as Dubai based on the purity of the metal.

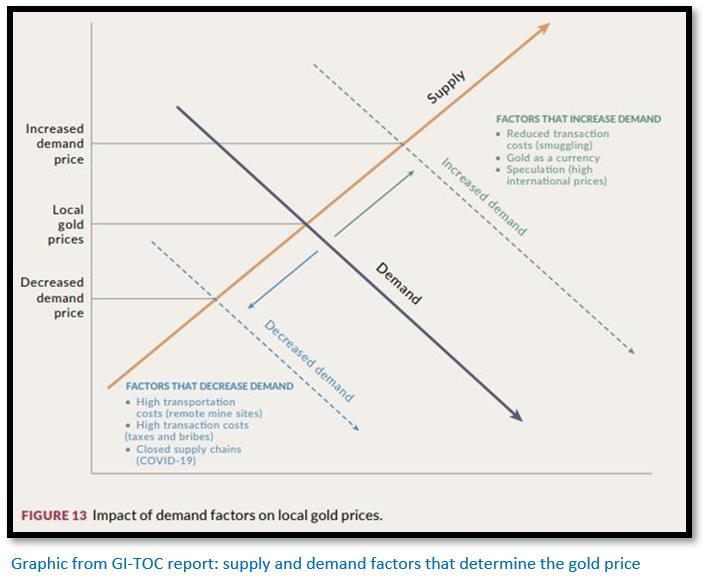

Local gold price volatility

It is generally assumed that prices further up the supply chain are consistently above prices at the mine site, while staying below the LBMA gold price. However, when gold supply is low or demand is high, prices will increase and the converse is also true.

Gold panning in Zimbabwe typically takes place between April – September in the dry season when river levels are lower, but a shortage of water to process ore can push up local gold prices. The COVID-19 pandemic with its lockdowns significantly decreased local demand and dropped local gold prices in 2020. However, gold prices are not just a product of legitimate market forces, but are warped because of corruption, criminality and violence and miners are often exploitated by buyers and dealers.

Factors influencing the gold price in Zimbabwe

Remoteness of mine sites: The report found that the less accessible the mine or trading point, the lower the gold price at source. This is because of the increased costs of reaching such mining areas, which reduces demand for gold from the area, and an increased number of buyers along the supply chain, each of which requires a profit margin.

Transport costs: low prices could be explained by high transportation costs to reach the more remote areas (for example, Makaha goldfield in Zimbabwe) or gold being of a lower purity than what was reported. However, significantly low prices are more likely the result of predatory gold buyers taking advantage of vulnerable mining populations in remote and conflict-affected locations.

Transaction costs: Gold smugglers can offer prices higher than the formal market buyers because they do not pay taxes on the trade or export of gold or other regulatory fees. In Zimbabwe, gold delivered to Fidelity Printers and Refiners (FPR) attracts a 2% royalty fee and the government has introduced a 2% Intermediated Money Transfer Tax which is paid on every transaction exceeding 100 Zimbabwean dollars (ZWL)

In addition, payments from the FPR can be slow, with some ASGM miners and buyers waiting more than two weeks for payment. The GI-TOC reported one miner as saying: “If I deliver a kilogram of gold today and I go for two weeks without getting payment, why would I deliver more gold to FPR when the black market is ready to pay cash?”

When buyers and dealers have to pay bribes to government officials, in particular Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) they may offer lower prices to people selling them gold in order to recover the financial costs. This reflects the vulnerability of miners in gold supply chains, as they make the smallest profit on gold and are the most likely to bear the brunt of transaction costs.

Exchange rates: The currency used can significantly affect prices. In Zimbabwe, unfavourable currency exchange rates make it hard for formal buyers to compete with the illicit market. US dollars are the preferred currency because of the volatility of the ZWL. For instance, on 4 May 2020, the official exchange rate was pegged at US$1 to ZWL 2,555 with the black-market rate at about US$1 to ZWL 45.

Because US dollars are more highly valued in Zimbabwe, gold will cost less if purchased in US dollars than in ZWL. The illicit market tends to pay full price for gold in US dollars and is therefore far more attractive to gold sellers than the Fidelity Printers and Refiners (FPR) who historically offered no or only a percentage of gold sales in US dollars.

Demand for US dollars also fuels partnerships between Zimbabwean nationals and foreign nationals with Zimbabweans providing a front for foreign operations, hiding their involvement and enabling them to use gold profits to buy luxury cars in South Africa, which they then drive back to Zimbabwe and sell to get their money back.

Paying prices near to or greater than the official gold price means the commodity is being used to move wealth from Zimbabwe to South Africa or Dubai and makes it impossible for legal, formal gold traders to compete with the illicit market on price.

VAT scams in South Africa

The GI-TOC report states that in South Africa this effect is amplified as the sale of second-hand gold products, such as jewellery, are tax exempt. “Gold that is either illegally produced or smuggled into the country is often disguised as recycled gold. Merchants then fabricate transactions that enable them to falsely claim that they have paid the 15% VAT and submit fraudulent requests for tax rebates.”

“As most of Zimbabwe’s gold is thought to be smuggled to South Africa, this could also be the reason for the high gold prices seen in Zimbabwe.”

Assessing gold purity

Gold purities at the mine site can vary from 50% - 95%. Various means are used to assess the gold purity by traders and miners ranging from its colour to specific gravity testing, the most common method of testing gold purity. The report states that middlemen usually pay a purity percentage that is two or three points less than the actual purity of the gold.

Equipment supply and mill processing

The GI-TOC report states: “Chinese nationals are also involved in supplying equipment and processing gold ore in Zimbabwe. In most gold mining towns, Chinese owned shops sell ASGM equipment, including mercury thought to be sourced from China. In the main production districts such as Bubi, Kwekwe, Shamva, Shurugwi and Kadoma, their position is dominant, cemented by the ownership of custom mill-gold processing facilities that employ more efficient technology than traditional stamp mills. Chinese nationals rarely buy gold not produced at their milling centres and reportedly offer competitive gold prices, especially when wanting to retain a trade relationship with a miner who has quality gold ores.”

Did the Covid-19 pandemic have an impact on Zimbabwe’s illicit gold mining?

The report concludes:

- “While legal gold mining operations and buyers were shut down in many countries by national lockdowns that placed severe restrictions on movement and trade, illegal mining and trade were only temporarily stalled or suffered from minimal disruption.

- Many illicit gold buyers responded to this disruption by either stockpiling gold at bargain prices (resulting in windfall profits when they were able to sell the gold) or developing new ways of moving gold.

- Furthermore, miners dependent on ASGM for survival continued to mine in many locations, increasing their vulnerability to criminal actors and bribe-seeking law enforcement.”

The report states that Zimbabwe’s first 21-day national lockdown in March 2020 brought the illicit market to a standstill, leading prices to plunge. While the official gold price was at US$56 per gram, gold was selling at between US$36 - US$39 on the black market by the end of March with the more remote the gold producing area, the more drastic the price decline.

However, Chinese nationals buoyed prices to some extent as they sought to maintain relationships with gold miners paying US$47 - US$49 before prices in main production areas recovered from June and continued to rise and by August was being traded at $60 and more per gram on the black market in Zimbabwe. Those with the means to stockpile, smuggle or export gold were able to reap substantial rewards.

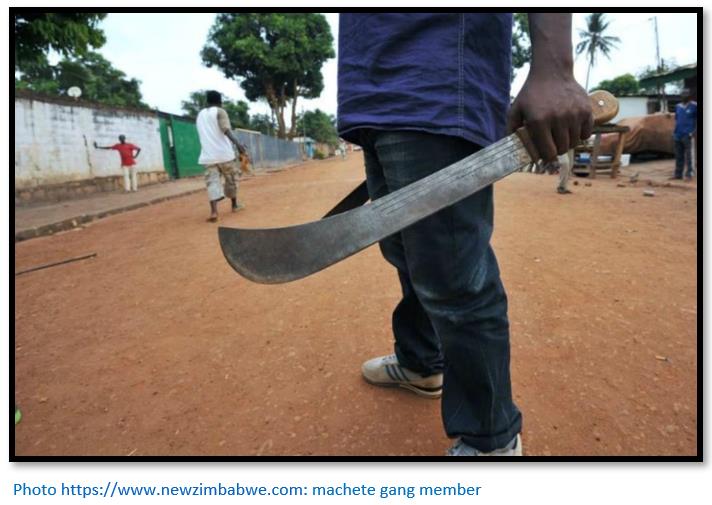

Violence at the gold sites

In Zimbabwe in 2019 violent gangs using machetes were reported to be forcing miners to sell their product at low prices and violence carried out by machete gangs against ASGM communities was becoming increasingly destructive and uncontrollable. In early November 2019, Zimbabwe Peace Project (ZPP), an NGO, reported[iv] that 105 people had been killed in the mining town of Kadoma in the three months from August to October, while hundreds of others were severely injured in these machete attacks between gangs fighting for the mining claims and to dominate the trade in gold. The machete hit squads, infamously known as MaShurugwi and Al-Shabaab, come from President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s home province of Midlands.

ZRP reported: “These figures (of murder cases and injuries from machete attacks) indicate that there is a marked increase in lawlessness in the area and innocent citizens are also suffering at the hands of mining gangs. This is further exacerbated by the fact that the gangs seem to be enjoying impunity as most of them continue without being arrested.” Those involved in the violence are never arrested as their patrons, who are suspected to be senior politicians, protect them.

Violence is a feature of gold rushes where senior ZANU-PF political figures try to secure ownership of mining claims. “If they are unable to secure permits, they may employ machete gangs (traditionally used for political violence) to displace ASGM miners, secure access to mine sites and, in some cases, steal gold ore.”

“Machete gangs tend not to mine, but rather rob miners of their gold, gold ore, money and other valuables. They also violently displace miners from profitable sites, extort money from miners and buyers and engage in forced labour. There are also reports of female miners being targeted, which has led many to stop working out of fear for their lives.”

Arrested members of machete gangs were released after arrest

“Allegedly, [machete] gangs were warned by ZRP insiders of planned visits and protected by officials of ZANU-PF, who are said to be invisible sponsors. Many members of the machete gangs were not captured or were quickly released on bail. In a survey of gold mining communities undertaken by the Zimbabwe NGO Centre for Natural Resource Governance, the names of politicians, including high ranking officials, featured prominently in answers to questions about machete gangs.”

Criminality in South Africa

In South Africa, criminal networks tightly control gold prices at the mine sites, with Zama Zamas often forced to sell at prices set by the networks of primary buyers. The report states that despite producing gold with a purity of up to 90%, Zama Zamas are paid between 25% - 75% of the current LBMA gold price.

“In South Africa, gangs and mining bosses are often the perpetrators of the most serious crimes at or near mine sites. They use violence to enforce discipline and ensure production quotas are met. Gangs and mining bosses also engage in violent gang and turf wars which each other, and with mine security and police. Based on media reports of inter-syndicate-related violence, it was estimated that there were about 300 mining-related deaths between 2012 and 2015, many of these the result of turf wars.”

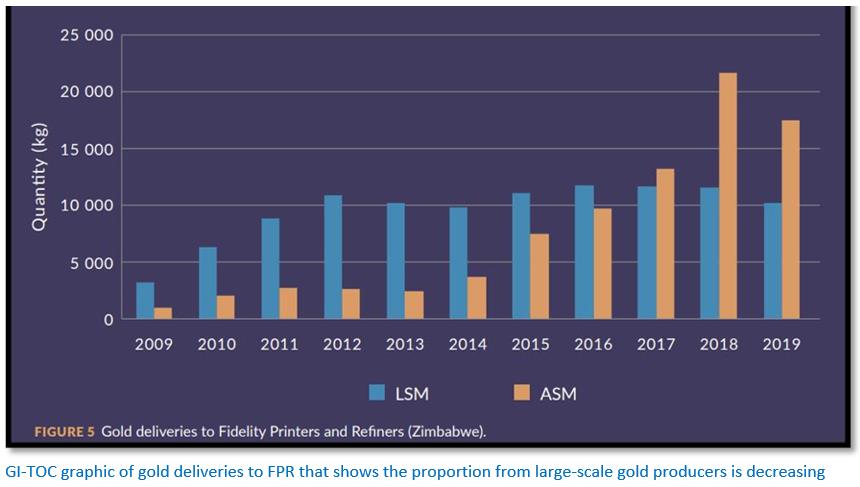

Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) as enforcers

In Zimbabwe gold mining is regulated by the Mines and Minerals Act, which is administered by the Ministry of Mines and Mineral Development. The gold trade is managed by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) through its Fidelity Printers and Refiners (FPR) subsidiary and the ZRP through the Minerals, Flora and Fauna Unit, enforce mining regulations and combat gold smuggling out of the country.

But according to gold dealers, ZRP district police commanders receive directions from their senior officials to provide security and cover for the illicit mining operations and the movement of gold. Some artisanal miners and processing centres will be targeted and subject to extortion rackets and bribery where they are known to be non-compliant with licensing regulations, others protected by the political elite, will be spared.

“In January 2020, the ZRP launched operation Chikorokoza Ngachipere to crack down on illegal mining. According to the ZPR, 52 115 people had been arrested by September as a result of the operation. While tackling machete gangs is crucial, informal ASGM miners suffered significant collateral damage in these operations. Non-violent miners and associated people were arrested and fined for offences that ranged from failure to wear personal protective equipment to not having identity cards. As a result, even legal miners stopped their operations for fear of arrest and gold deliveries to the FPR plunged to a 16-month low. In short, ASM miners were twice victimized, once by machete gangs and again by law enforcement.”

Gold supply chains

The GI-TOC report declares that “in East and Southern Africa, these gold supply chains are predominantly informal or illegal.” The state actors ensure that there is always a shortage of officially licensed gold traders, thus forcing miners to sell gold through informal or illegal channels although they may try to circumvent middlemen to maximise their profit.

in Zimbabwe, local miners from the Midlands Province do this by avoiding Kadoma, a consolidation point for the province and working directly with the big buyers in Harare. This may be because of the changes in political leadership, as Kwekwe, a Midlands town, is the hometown of President Mnangagwa.

The report states: “Nearly 40% of gold mined in Matabeleland is believed to be smuggled directly to South Africa. Smuggling is rife. Gold buyers revealed in interviews that they were selling between 10 – 30% of their gold to the FPR only to maintain their gold licences, with the rest being sold on the illicit market. Major foreign buyers, often from South Africa, partner with Zimbabwean dealers to buy large quantities of gold on the illicit market.”

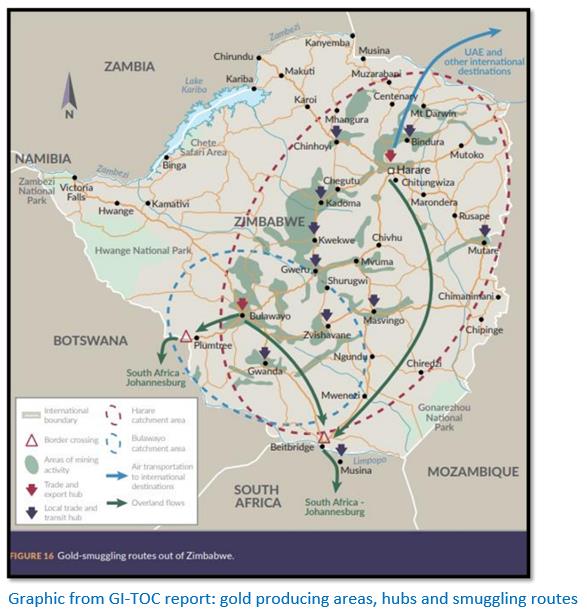

Trading hubs

In Zimbabwe illicit gold is moved to the trading hubs of Harare and Bulawayo before it is smuggled or exported out of the country. It is believed that Bulawayo buyers are generally less well-resourced and lack the US dollar buying power of their Harare competitors so that Bulawayo’s reach is limited to gold mined in areas close to the town, whilst Harare attracts gold from across the country.

Most African borders are extremely porous which facilitates gold smuggling

Gold is easily smuggled across international borders, both through informal and official border posts and mostly by road. In Uganda, Women and drivers of boda bodas (bicycle and motorbike taxis) often act as couriers for small amounts of gold that can be easily concealed.

Somali traders say it is easy to cross from South Sudan into Kenya with a Kenyan national identification card and they only need to pay a bribe if they are caught.

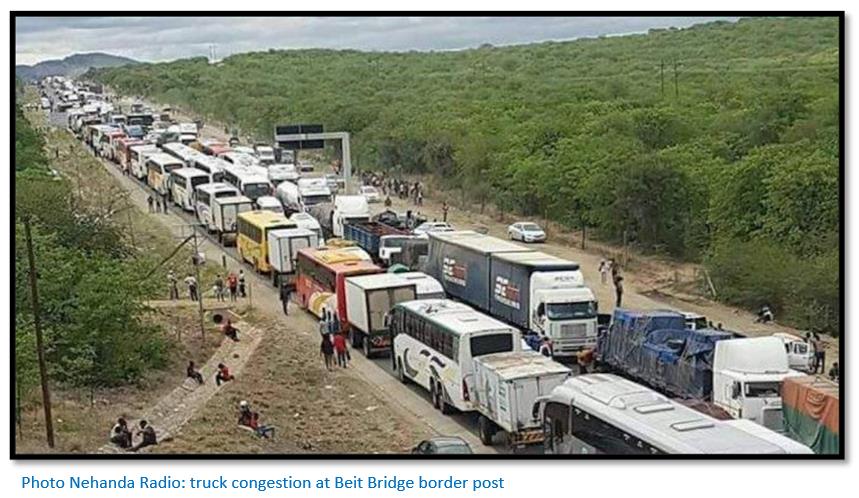

In Zimbabwe most gold is smuggled through the Beitbridge border post with smaller quantities of gold hidden in clothing and headdresses, while larger amounts are hidden away in vehicles. Both bus drivers and truckers are reported to smuggle gold bars through Beit Bridge weighing between five and 20 kilograms hidden underneath truck cabins, inside battery compartments and empty gasoline tankers.

In 2015, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) reported that the border was contributing to “… the most [gold] leakages that the country has ever experienced.”

The Botswana route has also been increasingly used due to congestion at Beit Bridge.

Border facilities lack inspection resources to deter smugglers

The report says: “On the borders, there appears to be a lack of capacity and will to stop gold smuggling. For example, in Zimbabwe, only luggage is subject to scans by customs officials so travellers without luggage are unlikely to be searched.”

With larger smuggling operations there is also collusion between criminal actors and border officials with the latter taking bribes to clear the smugglers’ path through border formalities. This is evident in the two articles on this website Rushwaya gold-smuggling case exposes a microcosm of the corruption that exists in Zimbabwe today and Oh dear, another foiled gold smuggling attempt is linked to the Zimbabwe President’s family; both articles are under Midland province on this website.

Export destinations for smuggling gold

The GI-TOC report affirms: “that in Southern Africa, Johannesburg is the regional gold magnet, although there are reports that significant and increasing amounts of gold are being exported directly from Harare to Dubai and other international destinations.”

in Zimbabwe smuggling gold out of Harare’s airport is suspected by the more powerful gold dealers and political elites. The articles referred to above would confirm this. It was reported that individuals moving gold as jewellery will make at least one to two trips each month with destinations in UAE, China and India and, to a lesser extent, Russia.

The destination of gold mined and bought illegally by Chinese nationals remains unclear. It is alleged that since they tend to work directly with government actors or diplomatic staff, they can easily fly gold directly out of the country to China through the main international airport. Many have good connections with the gold trade and are also involved in illegal mining and processing of gold.

In Johannesburg, locally produced gold and imports from neighbouring countries, especially Zimbabwe, is traded and laundered. Some is laundered into formal supply chains through local refineries. In South Africa police estimate that there are at least 100 small refineries in the Gauteng area alone.

From regional trade and transit hubs, most gold moves by air, legally and illegally, to global hubs such as Dubai. Moving gold by air often requires the influence of political elites or bribing airport officials. For smaller quantities of less than 10 kilograms, smugglers may directly pay security officials at check points. Alternatively, gold can be made into jewellery which is then worn by passengers on flights out of the country, mainly to India and the UAE.”

Foreign Buyers are mainly Chinese

The GI-TOC report believes foreign buyers are also fuelling the illicit gold trade. Where there is trust between foreign and major buyers in Harare and Bulawayo, foreign buyers will advance US Dollars to facilitate their buying gold and there is evidence that miners may give local buyers gold on trust to sell higher up the supply chain.

In most African countries there are: “laws that require foreign nationals to partner with locals in mineral enterprises that have been introduced to avoid the capture of mineral resources by foreigners. However, in practice it facilitates high-level corruption, with large amounts of money paid to political elites by foreigners, often in profit-sharing arrangements. For example, in Zimbabwe bans on riverbed mining and mining in protected areas have been lifted, allowing senior politicians and military chiefs to parcel out lucrative riverbed mining permits to foreign investors in exchange for hefty payments. Specifically, Chinese and Belarusian companies have been granted permission to conduct riverbed mining.”

The article Zimbabwe Mining Company Linked to Shady Deals With Belarusians under Manicaland on this website deals specifically with this problem. “Chinese nationals are also prominent and influential actors in Zimbabwe’s gold sector where they have formed partnerships with Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) elites, along with senior military and ZRP officers.”

The report states that: “While many nationalities are involved in gold mining and processing in these countries, the presence of Chinese nationals in the industry is notable…and the presence and influence of Chinese nationals in the Zimbabwe gold sector has significantly grown since 2010….The construction industry is thought to be a common cover for mining activity, an allegation also made in other African countries where Chinese firms are formally involved in construction and infrastructure projects, but are mining on the side. Informants say that have met Chinese investors who were officially in the country as construction workers on infrastructure projects, but who were also mining.”

However the report says that: ”The presence of Chinese nationals has become a political hot potato, with some politicians speaking out against the involvement of Chinese nationals in the mining sector as a way to gain political mileage with local communities.”

Political elites within ZANU-PF and the military are major actors in illicit gold smuggling

The report writes: “In all the countries studied, corruption was a common theme, ranging from small bribes to low-level officials to grand corruption by political elites. In South Sudan, Uganda and Zimbabwe, allegations of the involvement of military officers [Zimbabwe National Army and Zimbabwe Republic Police] and politicians at the highest levels of the ZANU-PF government abound. Foreign actors tied to corrupt agreements with high-ranking, influential politicians are also prominent actors in the regions’ illicit gold markets.”

These people have deep pockets and access to the right government departments which are all headed by those loyal to the ruling party ZANU-PF.

Recommendations from the article by Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) called Illicit Gold Markets in East and Southern Africa issued in May 2021.

Target key actors - Criminal investigations should target the activities of key actors in the illicit gold trade, including senior government officials. The report states by providing information and support, foreign governments and international law enforcement bodies can support efforts to identify and prosecute key individuals, companies and financial institutions linked to or involved in the illicit gold trade. This can lead to improved reporting on suspicious transactions and knowledge of laundering methods and flows.

Law enforcement, including customs officials, can also target enforcement activity at major transit points. International airports are key bottleneck points in supply chains, effective policing there will have a significant impact on illicit gold flows. Smugglers favour major border crossings when moving large amounts of gold. Targeting key road border crossings may therefore also reduce the ease with which gold is smuggled out of source countries.

Targeted sanctions can be used against key actors engaged in buying and smuggling gold that is used to finance armed groups and violence. Targeted sanctions, as opposed to more blunt country-wide sanctions, are critical to minimizing harm to vulnerable communities.

Dubai’s role in illicit gold dealing – Dubai’s prominence as a global gold and financial trade hub, requires action by the UAE government to curb illicit flows. The Financial Action Task Force Mutual Evaluation Report published in April 2020 provides guidance on steps the UAE can take on addressing vulnerabilities to gold and money laundering.

Strengthening relationships with ASGM stakeholders - Effective, sustainable responses and interventions will require a foundation of strengthened relationships with ASGM stakeholders. In particular, the influential role of intermediary buyers and their relationships with mining communities could potentially be of use. It is important to avoid initiatives and programmes supporting the industry being monopolized by a small number of individuals to the detriment of the larger group.

Making it easier for ASGM’s to comply with the law - effective responses to curbing activity in illicit gold markets require not only targeting influential criminal and corrupt actors, but also putting the tools, resources and support in place to make it easier for ASGM’s to comply with legal and regulatory requirements and to engage with the formal private sector. When legal and regulatory barriers to entry are too high (for example, costly licences or unrealistic environmental impact assessment requirements) it can force miners to operate illegally or rely on criminal actors to buy the gold they produce.

Making regulatory requirements cheaper for ASGM’s - In all the countries studied, miners said the current regulatory requirements were too onerous for them to comply including the high cost of mining licences as well as onerous and complex bureaucratic processes that need to be complied with.

In Zimbabwe current regulatory frameworks also create significant barriers to formalization for ASGM miners by creating compliance standards that are difficult to meet and delays in processing licences can lead to wait times of more than three years.

Formalize gold trading - Zimbabwe has taken steps to curb illicit flows and increase official gold deliveries. In 2016, the central bank (RBZ) directed the FPR to buy gold on a ‘no questions asked’ basis to encourage miners to sell all gold, regardless of the sources, within formal channels. However, because it is a criminal offence to possess gold without a valid mining or buyers’ permit, miners fear being arrested if they sell to official buyers. So, little artisanal mined gold finds its way to the formal market.

Establish a national gold buying schemes that pays in hard currency – the Zimbabwean government is constantly changing the percentage of the gold purchase price they will pay in US dollars versus local currency to compete with the illicit gold market. However, even when paying in US dollars, the FPR uses the official exchange rate, which is less favourable than the black market rate, which deters gold sales to the FPR.

Establish independent and dependable systems for ownership of mining claims

Proper systems to define property rights over mineral deposits are necessary to avoid conflict and corruption. Paper-based systems are vulnerable to criminal exploitation: electronic systems give greater accountability and transparency.

The GI-TOC report states artisanal miners must be able to register their claims and be supported by legal systems that can deal with conflicting claims to mineral deposits.

Minimizing barriers to entry for ASGM’s is required

Time periods of ASGM licences could be increased with reduced bureaucracy and delays. Reduced taxes or fees could be offered to buyers and dealers who engage with traceability and certification pilot projects and actively work to formalize their mining operations.

Domestic refineries to end cross border smuggling

Domestic refineries are a gold laundering vulnerability in supply chains, they also present an opportunity to establish responsible sourcing practices directly with the country of origin. They should strive to responsibly source gold, as opposed to refusing to source product from high-risk areas or disengaging from ASGM entirely.

The EU Conflict Minerals Regulation does not recommend de-risking supply chains by not sourcing from countries flagged as conflict or high-risk areas, but rather sourcing from them in a transparent and responsible manner. Also, it does not demand supply chains be completely free of conflict or risk. Rather, it expects companies to manage these risks honestly and transparently.

Better due diligence practices around recycled gold

Gold from conflict and high risk areas is often laundered through a select number of transit hubs and sold on as scrap or recycled gold. Inadequate due diligence by importers of recycled or scrap gold material could therefore allow high-risk supply chains to be left unchecked. Companies that import recycled or scrap gold ought to seek additional information from suppliers on the steps they have taken to comply with the OECD guidance rather than uncritically accept the accuracy of all material designated as scrap or recycled metal.

Better cooperation between government agencies

Increase cooperation between government agencies such as law enforcement, customs services and other relevant bodies to combat criminality. In both source and destination countries, competent authorities need to be adequately staffed, funded and trained. Communication strategies between government bodies at the national level are also needed to close coordination gaps.

Enforcement should also focus on transit and trade hubs, particularly the strengthening of enforcement controls at airports. Land borders are difficult to police, while the geographically remote and dispersed nature of ASGM makes it a challenge to regulate mine sites.

References

Marcena Hunter, Mukasiri Sibanda, Ken Opala, Julius Kaka, Lucy P. Modi. Illicit Gold Markets in East and Southern Africa. Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. May 2021. https://globalinitiative.net/

Gift Nthuli. Going for Gold - Supporting the extractives industry. UNDP. 31 Jan 2020. https://www.zw.undp.org/content/zimbabwe/en/home/blog/going-for-gold---s....

Notes

[i] The GI-TOC report states that the estimated 30,000 Zama Zamas in South Africa are at the lowest rung of the mining hierarchy. An estimated 70 per cent of these are foreign nationals, mostly from neighbouring countries such as Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Lesotho. Generally from poorer socio-economic backgrounds, Zama Zamas are typically vulnerable individuals exploited by criminal gangs. They can be unaware that they have been recruited to mine illegally until they arrive at the site and are then forced to work underground for weeks, and sometimes months, before resurfacing. These miners are also exposed to murder, forced migration, money laundering, corruption, racketeering, drugs and prostitution on a scale not seen elsewhere in Africa. A recent trend in the trafficking of children has been linked to increasing numbers of underage minors being rescued from forced labour in mines in the past two to three years

[ii] F. Todd. 18 Sept 2019. The plight of the Zama Zamas: A perilous hunt for gold in South Africa’s abandoned mining network. https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/features/zama-zama-gold-south-africa/

[ii] Staff reporter. 27 Dec 2020. Chiwenga's 'brother' implicated as foreign firms defy govt ban on river bank mining. https://bulawayo24.com/index-id-news-sc-local-byo-196868.html

[ii] Cyril Zenda. 9 Dec 2019. Who is behind machete killings in Zimbabwe’s goldfields? https://www.fairplanet.org/story/who-is-behind-machete-killings-in-zimba...