Some important Shona customs and ceremonies

By Peter Sango

These stories of Shona Customs were first published in 1970 and were amongst the best essays received in a nationwide essay competition on Shona culture and tradition. Their authors ranged from a 15 year-old schoolboy to a university student and they came from Sakubva in Mutare to Berejena Mission near Masvingo.

Although more than 50 years have passed since the essays were written and many aspects of Shona customs have changed, it is hoped that the stories will give insight into what many parents and grandparents of the present generation learnt from their own relations in the 1960’s.

Mambo Press, originally established by the Catholic Church at Gweru, publishes a wide selection of books in many subjects and for a wide audience.

Introduction

The Shona have many traditional ceremonies to mark significant occasions such as marriages, births, and deaths. Because of European influence, most of the ceremonies have ceased to exist, but a few still take place.

Mashavi (Spirits)

This is a traditional ceremony which has been practised for a long time. It is an occasion when dead people state their needs and grievances through living ones. This take place in three ways, namely: jukwa, chipunha and chingweme. Before the ceremony takes place, beer is brewed by old women who are past child-bearing age. Many people are invited and among the important guests are well-known N’angas. On the day of the ceremony, the person with the spirit sits in the centre of the house and a pot of beer is produced. A short prayer is offered and the person with the spirit drinks first and then shares the beer.

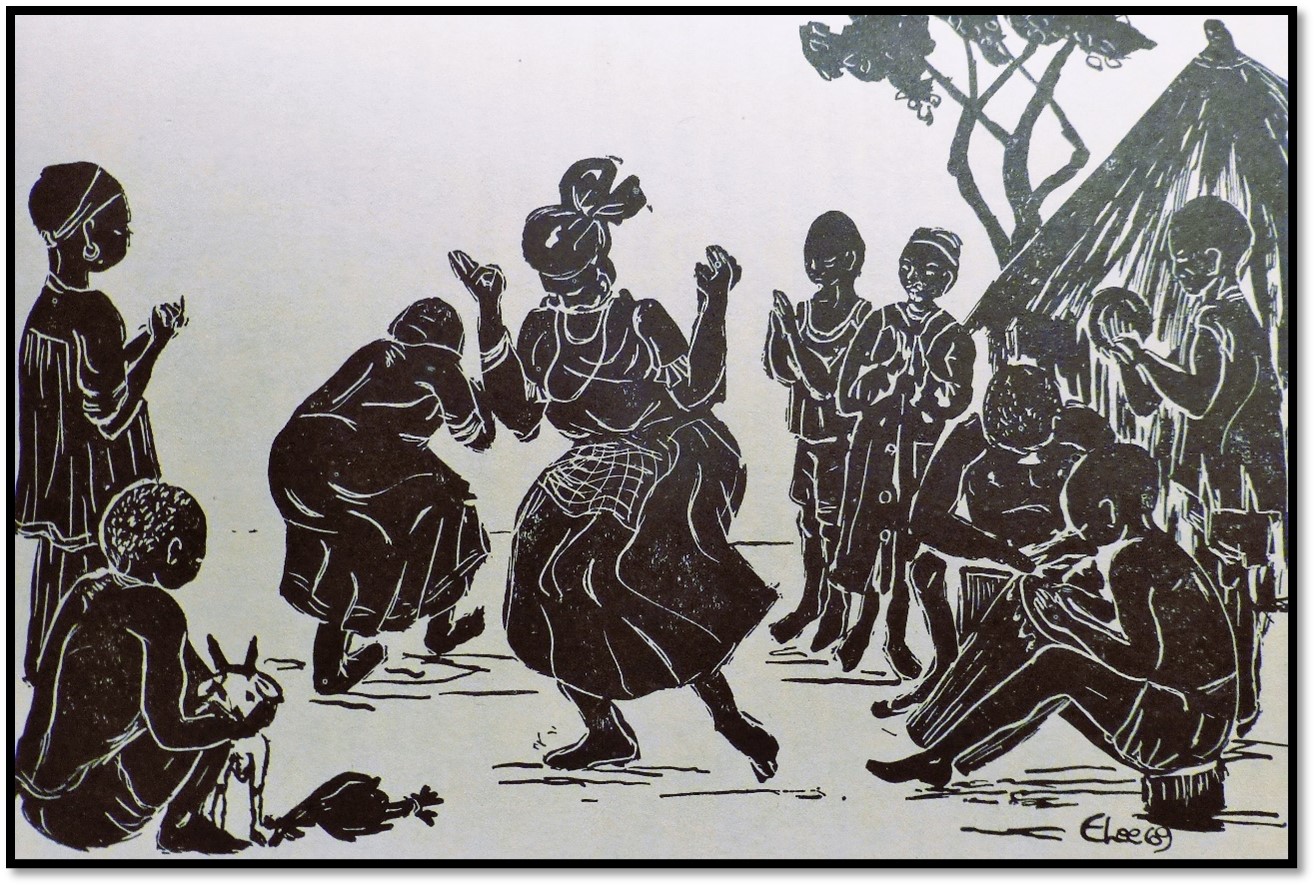

Later, big pots of beer are brought and people sing and drink. The songs are accompanied by drums and rattles (hosho) This is followed by traditional dances. At the climax of this dancing and singing the person concerned receives the spirit and begins to dance differently from the others. The possessed one may dance headlong or climb to the rooftop to dance. He may rush to the cattle kraal, gather fresh dung and devour it. He may be forced by the spirit to gather tobacco, grind it, mix it with water and drink the mixture. He may kill chickens with his bare hands and eat them raw. All of those possessed speak in languages which they cannot speak when normal and only the N’angas can understand and interpret what they say.

Kuruva Guva (The bringing home ceremony)

When an adult dies in Shona society it is believed that he will return to his relatives after the kuruva guva ceremony has been held. Before the ceremony, the deceased person is considered to be separated from their family’s ancestors and therefore it is forbidden to offer sacrifices or prayers to him. The kuruva guva is held a year after death. A week before the ceremony, beer is brewed and a beast is selected for the occasion by the closest relatives of the deceased. On the day of the ceremony, the beast is slaughtered. The relatives then take a small pot of beer to the grave and a prayer is offered. Later the people mourn their relative for the final time at the grave. Before leaving the grave, an old man tells the deceased that he is now a member of the ancestral spirits (vadzimu) The group returns to the village where an enclosure has been built of wooden poles and grass. Here funeral songs of sung accompanied by drums. Singing lasts all night; beer is drunk at intervals and roasted meat is eaten without salt. After the ceremony, the deceased is a member of the ancestors and prayers and sacrifices can be offered to him.

Mukwerere (To ask for rains)

Mukwerere is an important ceremony which seldom takes place before summer. It is performed when drought threatens. A svikiro (medium) is responsible for the rain. He is a man whose hair will never be cut; once it is cut, there will be no rains until it grows again. He wears only black and red clothes. He is greatly respected and no one may insult or disobey him. His main work is to attend tribal dances arranged for him. During these dances, drums and the mbira are the main instruments. Gifts are offered to him in the form of crops and small animals like chickens and goats.

When drought threatens. the people informed the svikiro that they would like to hold a ceremony. When he gives his permission, the old woman take corn porridge (masvusvu) and tobacco at sunset to the place of the ceremony. They pour it on the spot and return to their homes. In the morning they go to the place and spread blankets. Later in the morning the whole tribe led by the svikiro gathers at the spot. When they arrive, the svikiro sits in the centre on top of the blankets and people sing and dance. Usually rain begins to fall during the ceremony, but it would never fall on the place where the svikiro sits. The Shona believe that rain always avoids him.

Kugadzwa Zita (To give a name)

When an adult dies, his or her name is given to someone else so that it may never be forgotten. Usually the name is given to a grandson if it is a man and to a granddaughter if it is a woman. The elders buy a black cloth and if the deceased was a woman, black beads are also bought. On the day of the ceremony, the person to receive the name sits on a mat and the leader of the family says: “You are now the father of the family; anything we want we will direct it to you. As our father, we humbly ask you to protect us.” The leader drapes the black cloth around the seated one and turns to the other members of the family and introduces him.

Mombe yeGono (The Ancestral Bull)

In every home there should be an ox or bull for the spirits (mombe yeGono) This ox does not plough at all and is not killed. When the owner of the animal (the spirit) needs it, a ceremony is held. Beer is prepared and on the day of the ceremony, the bull is slaughtered. Then the guests and the closest relatives drink its blood. They eat half the liver and other parts raw. They sing songs of praise and drink beer throughout the night. At daybreak a leader says a prayer.

Marombo (To thank the Spirits for the Crops)

This ceremony is held when the crops are ripe, sometime between March and April. Before this ceremony, no child is permitted to touch or eat any crops from the fields. When the crops are ripe, the kraalhead or the headman collects a sample of each crop. These are taken to a tree trunk and the person in authority says to the crows; “Here are your meals, keep away from our fields.” Then the people are led to a muhacha tree. A small part of each crop is collected and the head of the group kneels under the tree and prays to the vadzimu: “Help us to keep the crows away and also help us to eat the crops without illness.” After this, the people are led to the fields, two cobs of maize are collected and roasted. One is given to the headman's youngest child and the other to the youngest child of another family. After this, people can harvest and eat their crops.

Kugadza Nhaka (To give a husband to a widow)

This ceremony is very old, but today its popularity is decreasing because Africans are becoming westernised. If a man dies leaving a wife or wives, a close relative has to take the responsibility for these women and their children. He may be the younger or elder brother of the deceased, his uncle, or the elder son of another wife.

On the day of the ceremony the wife or wives sit on a mat and the prospective husbands sit nearby. Prayers are offered to the ancestors, especially to the deceased husband. The woman is asked to select another husband. She does this by taking a dish of water to the man of her choice. After this, a short ceremony is held to inform the deceased that his wife and children are in safe hands. The chosen man takes on the responsibility of the wife, her children, and any other property of the deceased, including livestock.

This is the custom of the Zezuru; the Karanga do things differently. After the husband has die his clothing and weapons are hidden and the wife is given someone to protect her. The man may look after her for three or four years, but not as a husband. Before the ceremony is held the woman's relatives are invited. Both families are serious and they may not speak to each other. The next morning the deceased man's knobkerries are laid across the doorway. The widow is asked to walk over the Knobkerries into the room and out again. This is a sign that she did not commit adultery. If she had committed adultery, she could not across the knobkerries without falling. Once he has passed the test, an old lady leads the woman to a mat and as mentioned above, all the suitors sit around. She carries a dish of water to the man she chooses. If he accepts he claps his hands and washes them.

Chitsinha (indisposition to marriage caused by a spirit)

This occurs when a man or woman dies unmarried. He or she may possess someone of the opposite sex and the spirit will come to that person and say: “I am so and so who died a bachelor and I have chosen you to have my spirit. Therefore you will not marry.” As soon as it is known, a ceremony is held at once if the spirit is accepted. Prayers are offered and the person is called by the name of the deceased.

Although these ceremonies are losing their popularity. They still continue to be meaningful to people.

Reference

Clive and Peggy Kileff (Editors) E. Lee (illustrations) Shona Customs. Mambo Press in association with the Rhodesia Literature Bureau, Gwelo, 1974