Roora and Marriage

By Lydia Janhi

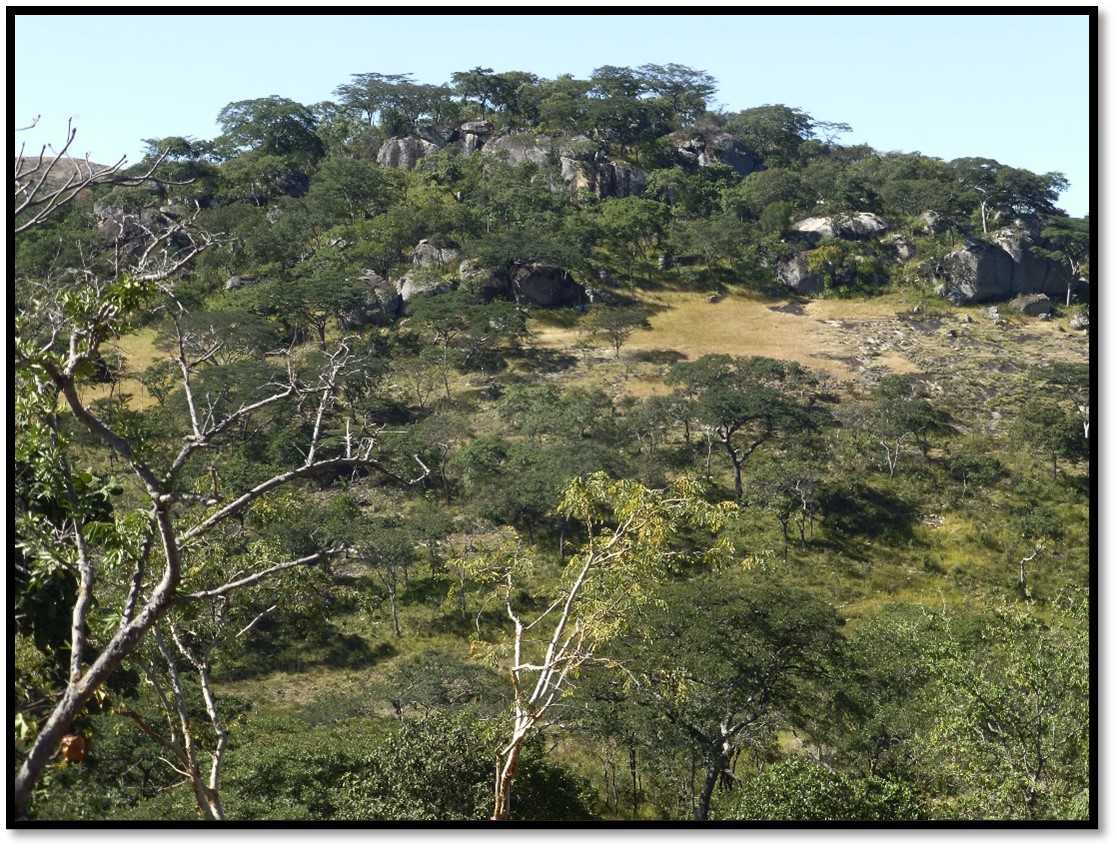

These stories of Shona Customs were first published in 1970 and were amongst the best essays received in a nationwide essay competition on Shona culture and tradition. Their authors ranged from a 15 year-old schoolboy to a university student and they came from Sakubva in Mutare to Berejena Mission near Masvingo.

Although more than 50 years have passed since the essays were written and many aspects of Shona customs have changed, it is hoped that the stories will give insight into what many parents and grandparents of the present generation learnt from their own relations in the 1960’s.

Mambo Press, originally established by the Catholic Church at Gweru, publishes a wide selection of books in many subjects and for a wide audience.

Origins

Long ago, before the coming of Europeans, roora or lobola as it is called, was different from what it is today. Parents used to be responsible for finding suitable husbands for their daughters. They chose those husbands according to their characters and the selection usually took place when the daughter was still very young. However, many girls resented this and some even ran away from their husbands to marry the men they loved. This system was not good because it sometimes caused disaster in the family.

The parents of these girls were given one or two cows and a few bags of maize or rapoko. No money was given. Sometimes the suitors went to their in-laws to plough or work in the fields as payment for their roora. Those who had dogs went to the forests to hunt and brought game to their in-laws to pay the roora. In areas where food was scarce, parents exchanged their daughters for food. Sometimes roora was only a bucket of maize, rapoko or mhunga.

However, as time went on these marriage customs changed. By the time the Europeans came many people were allowing their daughters to marry the men they loved. But if the man lived so far away that the girl’s parents did not know his character and behaviour, the daughter would not be permitted to marry him. Girls could marry those men who lived nearby and whose kind of life was known to their parents. Hard work was given to the man who wanted to marry so that he had an opportunity to prove himself. This is no longer the custom.

Customs changed rapidly after the coming of the Europeans and roora has increased so much that some of the younger generation now oppose it. Today, no girl is given to any man, but each may choose a suitable husband for herself. But some parents still do not allow their daughters to marry men from distant places. The man who is ready to marry has to have plenty of money since the in-laws doors demand a lot of roora. At first, the suitor is brought home by his fiancée, but he is not invited until he has expressed a desire to marry. Parents will not allow their daughter to bring her boyfriend’s home until she is old enough to marry. After the young man has been brought to the girl’s home, her family begins to think about roora.

This money is not carried by the suitor himself, but his parents choose one of the old men who knows about marriage customs. This man is called munyai. When the munyai arrives at the home of the in-laws, he is not supposed to go directly into their house but should go to a neighbour’s house so that the owner of this house may accompany him to the home of the in-laws. If the munyai should go directly into the house of the in-laws he will have to pay about $4 as a fine for breaking the rule. When they reach the in-laws house the munyai announces the object of his visit. He places some money in a wooden plate and places the plate in the middle of the floor.

The girl and her relatives were all be present. The girl is asked to take some money from the plate, but she does not do this herself, a sister or a friend will do it for her. She tells this person the amount of money she wants. Today most girls take between $20 and $25. Those who take less are not virgins and have children already. The appointed person picks up the dollars one by one. If all the men present, including the munyai think that she took too much, they ask her to return some of the money. Before this, the munyai pays masunungurahomwe to be able to take the money out of his pocket. This is it usually about $3. Next he pays makandinzwaani which means “who told you I had a daughter?”

After this the father takes the amount of money which he thinks is enough for the roora of his daughter. Some fathers take about $60 or $80. This is called rusambo and the amount depends on whether the parents took much trouble in caring for their daughter. If the girl was ill and the parents took her to the hospital they may demand more money for her roora to replace the money they spent on her. If the daughter has been to school, the parents may demand money to reimburse them for school fees. These days, some parents may demand about $140 to $180.

After the father has taken his share, he also takes some for the mother. Long ago, the mother was not allowed more than $20, but these days he may take $30 or more. After the larger part of the roora has been paid, all the members of the family are called together for the ceremony. The suitor brings a cardboard box full of bread, tea and other things. Everyone eats to their hearts content. If there is not enough food to feed the entire family, the suitor is mocked and told to go and buy some more. After this ceremony all the married daughters of the family return to their homes.

Next the suitor is asked to buy a dress, two blankets, a belt and a pair of shoes for his fiancée’s mother. For the father he must buy an expensive coat, a hat and a pair of shoes. If he doesn’t want to buy these things himself, the suitor can give the father-in-law money instead. The man who is ready for marriage should have saved a lot of money before he expresses his desire to marry. Sometimes the suitor is given about two months to prepare these things and deliver them to the in-laws. Then he can prepare for the wedding.

Elopement

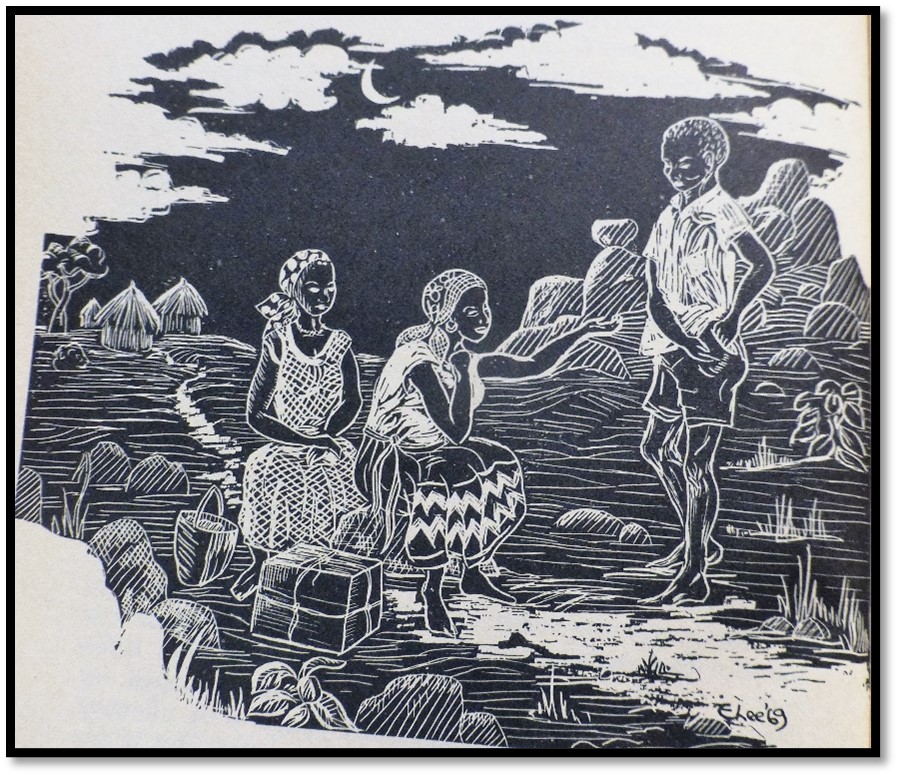

If the man has slept with the girl before playing the roora, then he must take her to his home without her parents’ knowledge. The boy and girl arranged when and where to meet. The girl collects her things without attracting attention and at night, she and one of her friends carry their belongings to the place where they arranged to meet the boy. This place should not be far from the kraal or the girls will be afraid to walk there in the dark. When they meet the boy, the three of them head for his kraal. He will have told his parents and relatives that he is bringing his wife home. The family make arrangements and are ready to meet the visitors. Little girls and boys wait up for the two women even if they arrive after midnight. They are greeted with singing and drums.

As soon as the two women and the husband are about a mile from his home, the women sit down every few yards and only stand up when they are given money. The money is given to the bride’s friend: she is in charge of all money given to them. When they reached the man's home the girls and boys and all the members of the man's family come out to meet them. The bride covers her face and will only show her face to those who first give her money.

The people spend that night singing and drumming to welcome the new wife. The next morning, the two women go and fetch water and boil it. Then they carry water to each member of the family to watch their face and hands and feet. After each person has finished washing, they will put some money in the dish. The two women then boil water for the man's mother and father; they are given more water than anyone else. After washing they too give the women money. When all members of the household have finished washing, the women carried boiled water to the family’s relatives who live in that village. They give each one of them some water for washing. Again, the women are given money by each person.

Then the women return to the man's home and sweep the whole courtyard leaving all the dirt in a heap. They wait to be given money before removing the dirt. Next they clean all the houses and are giving some more money. Then the girl’s friend returns home to their village, leaving the new wife alone with her in-laws.

After about two weeks, the husband’s parents send a messenger to the girl’s parents. This messenger must be strong and careful. He is given $1 to carry to the in-laws to tell them where their daughter is. The messenger goes to the in-laws very early in the morning when they are just getting up. He goes round all the houses making sure that no one sees him. When he sees a window or door which is open he throws the money into the house. shouting the name and surname of the man intending to marry their daughter. Immediately afterwards he runs away for if he is caught he will be beaten.

Before this money is brought to the in-laws the girl’s father and brothers scold her mother saying that she knows where their daughter is and asking her to tell them. Sometimes the girl has told her mother where she is going, but other times she leaves without telling anyone. When this money is paid, the mother is happy and relieved of her burden. The bride groom’s parents then prepare money for roora, but first they will pay damages for ‘spoiling’ the girl. Once it was only $30, but now it's been raised to as high as $50 or more. This money is not counted as part of the roora.

The Wedding

The man who marries without first ‘spoiling’ the girl prepares for a wedding party immediately after the roora has been paid. He buys wedding garments for his wife and her bridesmaids. The in-laws provide an ox to be killed at the feast. Beer is also prepared. All the relatives are called to help in cooking the beer and food. Dancing and singing with drums begins as soon as a number of people have gathered. The bride and groom and the bridesmaids first go to church. After that they return home where many people will be awaiting their arrival. A shady place is set aside in the courtyard where the bride and groom and bridesmaids sit facing the crowd. Singing and dancing continue until mid-day, when the bride and bridesmaids may change from their wedding garments to their own clothes.

At lunchtime over people sit under the trees in small groups where they are given sadza and meat. The wedding party have their lunch in a special room. After lunch they return to the courtyard and the singing and dancing resumes. Those who brought gifts hand them to a man whom they call the ‘shouter.’ He raises the gifts for all to see. The groom's parents are first to present day their gifts and they are followed by the bride’s parents. Then other relatives and friends follow. When everyone has given their gift, the money is counted and the shouter announces the total as well as the other gifts. After much cheering, the gifts are taken away and the dancing begins again.

Later during another break, pots of beer are passed to the crowd. The women and those who do not drink beer are given slices of bread and tea. After this, the dancing continues. At dark some people leave, but others remain and sleep there.

The following day the people go to the man's home where many people will be waiting to welcome the wedding party. There will be singing and dancing as on the previous day and in the evening the bride and groom cut the wedding cake. They cut it in the middle and then the groom’s elder sister (if he has one) or his eldest aunt, cuts the cake into smaller pieces and gives it to the old people. Then the girl is given to her husband formally. The eldest of the man’s sisters shows them to their room and the bride is given money to change into her night clothes and get into bed.

The First Child

After the wedding the girl stays with her in-laws for seven months. Then she is taken to her parent’s home where she will stay until she gives birth to her first child. Her parents receive an ox which is killed and some money which they called masungiro. This money is to pay the parents for taking care of the man's wife. The in-laws also pay $4 to enable both families to meet and greet each other: this is called kuombera. Then the in-laws pay either three goats or $18. The husband’s messenger brings these, but the husband is also present to kill the ox and prepare the meat. When sadza and a very big pot of meat have been cooked, the girl's mother cuts a large portion of sadza and meat from her own plate and hands it to her son-in-law. He eats this while sitting on a mat. He is not allowed to sit on a chair or stool in his in- laws home until his child is over thirteen years of age.

Marriage of Relatives

If two cousins want to marry, their parents are reluctant to allow this. But if the parents see that the couple are really in love, then they say that the suitor should pay a fine for breaking the rule. He must pay an ox, a piece of black cloth and some money. This rite is called kucheka ukama. (the ritual cutting of kinship ties) Even distant relatives are not allowed to marry without first paying the fine for breaking the rule. Then they must pay roora as well. The ox is killed and the meat shared between the two families. The piece of cloth is cut in half to show that the relationship between the two families has been broken. The money is used by the girl’s family. When this has been done, the marriage customs follow the usual course.

Divorce

If there is a divorce, the husband sends his messenger to demand return of the roora. A couple who want to divorce must first go to the chief of their area. The chief tries to settle the dispute between them and may wait some time to see if the quarrels between them continue. If they continue to quarrel, they go back to the chief to ask for a divorce. The chief questions them both and allows them to divorce if they give sound reasons.

The woman goes back to her parent’s home. If she has small children, she will take them with her and look after them until their father comes to take them to his own home. If the woman's parents are dead, she will go to her eldest brother and explain her difficulties to him. The husband sends his messenger to demand back the roora. The amount of roora to be returned depends on the number of children born to the couple. If there are many children none of the money is paid back except for the first part of the roora. The cow given to the woman's mother is not returned. If this cow is returned, disaster will come to the children. The ox killed when the wife was accompanied to her home after staying seven months with her in-laws is not replaced.

If the woman bore no children everything will be demanded back except the cow given to her mother and the ox killed after the marriage. This is difficult if the woman's parents have used up the roora; this is one of the reasons why they try to prevent their daughter from divorcing. Some men are in a hurry to get their money back since they want to remarry. If the in-laws refuse to return the roora, trouble may begin between the two families. This trouble is only settled by the chief.

Today, many fathers spent all their daughters roora quickly because they fear having to return it in the event of a divorce. Many girls do not behave well and when they marry their parents are afraid to ask too much roora.

Reference

Clive and Peggy Kileff (Editors) E. Lee (illustrations) Shona Customs. Mambo Press in association with the Rhodesia Literature Bureau, Gwelo, 1974