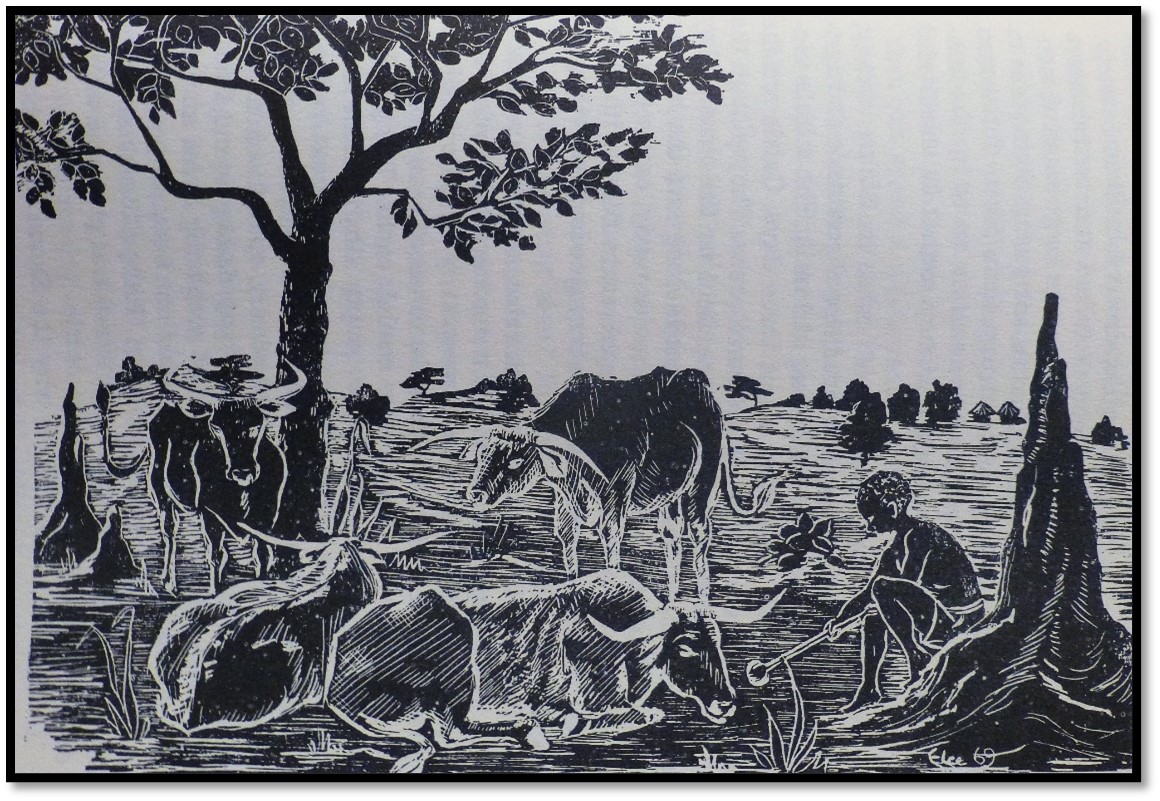

Cattle: the life-blood of Shona Society

By Fidelis Bere-Chikara

These stories of Shona Customs were first published in 1970 and were amongst the best essays received in a nationwide essay competition on Shona culture and tradition. Their authors ranged from a 15 year-old schoolboy to a university student and they came from Sakubva in Mutare to Berejena Mission near Masvingo.

Although more than 50 years have passed since the essays were written and many aspects of Shona customs have changed, it is hoped that the stories will give insight into what many parents and grandparents of the present generation learnt from their own relations in the 1960’s.

Mambo Press, originally established by the Catholic Church at Gweru, publishes a wide selection of books in many subjects and for a wide audience.

It is no surprise to a young man who comes from a rural area and works in town to receive a letter from his father or mother asking for an appreciable amount of money. In Shona society this is common and in most cases the money will be used to buy a cattle. When a young man possesses cattle he will be on the road to manhood. These cattle will prove their worth later when they provide support and security to the young man.

A family without cattle in Shona society is like a house built on sand or a house build of cards which soon crumbles. Indeed, cattle are the enduring foundation of traditional Shona society.

Cattle have a social role and form an effective bridge to connect relatives and give meaning to friendship. If a man decides to slaughter an ox or a cow just for the sake of meat, you will find that the whole extended family will be present and all the men of the village will help to skin the ox. After skinning, the men roast the meat. Lungs are usually given to grandchildren and nephews of the owner, pancreas to the herd boy and other parts to certain other people. The bulk of the meat is distributed to the relatives and friends so that in the end the owner of the ox may remain with less than half. This illustrates a Shona proverb: “Ukama igasva hunozadziswa nokudya” meaning that verbal friendship is not enough, true friendship is proved by free meals and gifts.

Not only do cattle support friendship among the living, but they also unite the living with the dead. Roasted meat is eaten unsalted at ceremonies in honour of the dead. Even live cattle are offered to the ancestors. It is customary to find two cattle in a man's kraal which cannot be sold, one is an ox for his dead father and the other is a cow for his mother. Should a man failed to set these beasts aside, it is believed that there will be illness in the family.

In the case of roora, cattle have yet another function - they link together the two families concerned. Long ago it was enough to pay roora with a few mice, a log of wood or by working for the father of the girl. However, all these were replaced by cattle. This noble custom of roora is supposed to be a safeguard against divorce in Shona society, but unfortunately it has been distorted and turned into a lucrative business by those who charge large sums of money and many cattle. Today, cattle are losing their place in roora because young men can pay cash. Even if the man has money he must still find two cattle: an ox for the father and a cow for the mother. Money cannot be substituted for these two.

Apart from these functions of cattle in Shona society they play an essential role in traditional economic and agricultural life. Cattle provided meat and milk. The milk is consumed as sour milk after about three days. Cattle are the bulwark of agriculture in the rural areas. They plough the fields and carry crops from the field to the kraal. They provide manure (a mixture of cattle dung and the remains of the crops) and when the manure is ready, cattle pull the carts to the fields. Cattle also pull carts filled with maize to the grinding machines and carry goods from village to village.

After about seven years of service, an ox may be sold. The average price is about $20 but some fetch up to $40 or $60. The money serves as a weapon in chronic battles against hunger and school fees. In times of hunger the Shona don't worry if they possess enough cattle. The problems of school fees is threatening to empty all the cattle kraals. Indeed, if suddenly the Shona were left without cattle by some natural disaster, then over half the students would be financially crippled and consequently out of school. Also cattle have always been used to pay damages and fines of the tribal courts. The custom of preparing hides and skins for clothes and blankets has died out because people have turned to manufactured clothing. Today the skins are either sold to shoe companies or sliced and prepared as ropes or whips to inspan and drive cattle.

One of the main reasons why the Shona try to hoard as many cattle as possible is to have prestige and fame. In Shona society one’s social status and wealth are determined by numbers of cattle. Thus to have many cattle is the summit of a Shona’s desire. Except in cases of extreme necessity, a Shona does not sell his cattle. A man maybe dressed in torn clothes and lack many things and yet have twenty-five cattle in his kraal. He will not part with one of these cattle for fear of being lowered on the social scale.

Keeping cattle provides a link between neighbours. The people of a whole village take turns herding the cattle and there may be as many as 300 head of cattle in the herd. Each family herds the cattle for two days and then can spend a whole month without worrying about the cattle until their next turn comes. Anyone who does not herd the cattle properly faces a painful suspension from the dzoro during period he will look after his own cattle alone.

In most areas a serious problem is arising. The people’s desire to have many cattle is trying to dance in time with the need for more arable land and these two desires often cannot keep step with each other. Young men want to be given plots of land and to buy cattle. But where will these cattle graze since the grazing area is reduced by giving plots to young men? In my area about 700 cattle, 80 donkeys, 500 goats and sheep all graze on area about one mile wide and four miles long. As a result, the cattle are of very poor quality and many of them die each year. Some of these unfortunate weak animals cannot even pull a plough in teams of four.

For the future, money threatens to replace cattle in roora. Also, money may well take precedence as a source of prestige and pride. Already the tractor is taking over the task of ploughing. No doubt, in time to come cattle will no longer provide security against hunger for those who work in town. However, cattle still are a source of pride and they foster friendship and create relationships between people. They will remain for some time the life blood of Shona society and one of the main vertebrae in the backbone of this society.

Reference

Clive and Peggy Kileff (Editors) E. Lee (illustrations) Shona Customs. Mambo Press in association with the Rhodesia Literature Bureau, Gwelo, 1974