Cattle and Social Status

By D.H. Makamure

These stories of Shona Customs were first published in 1970 and were amongst the best essays received in a nationwide essay competition on Shona culture and tradition. Their authors ranged from a 15 year-old schoolboy to a university student and they came from Sakubva in Mutare to Berejena Mission near Masvingo.

Although more than 50 years have passed since the essays were written and many aspects of Shona customs have changed, it is hoped that the stories will give insight into what many parents and grandparents of the present generation learnt from their own relations in the 1960’s.

Mambo Press, originally established by the Catholic Church at Gweru, publishes a wide selection of books in many subjects and for a wide audience.

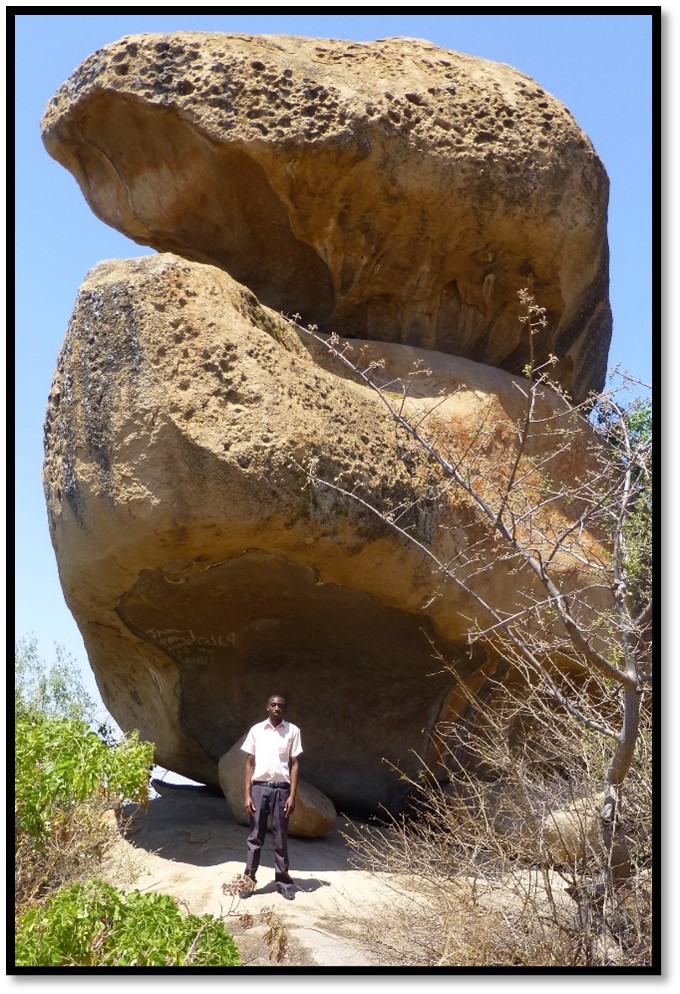

Cattle are the pivot of life in Shona society. They are used to satisfy a great number of needs. First and foremost, they are regarded as the most essential source of wealth. A Shona man calculates his wealth in terms of the head of cattle he possesses. Thus these cattle are highly esteemed. Every day when they leave for pastures and when they are brought back at sunset, they are counted. A man gains great satisfaction seeing his cattle kraal teeming with cattle. They are not to be slaughtered but left to increase their numbers and thereby his wealth.

A man’s social status is determined by how many head of cattle he possesses. The larger his herd, the more he is regarded as an important person in his society. Cattle elevate him socially. The man with the largest herd gets the greatest honour at all functions – social, ceremonial, ritual. He occupies the most prominent place at the chief’s court. The tribe fears him and the chief favours him with visits. On such an occasion, he may slaughter a beast to celebrate with the chief.

Cattle play a significant role in roora. This is a custom in which a man demands cattle in exchange for his sisters or daughters when they marry. The prospective son-in-law pays a specified number of cattle to marry another man’s daughter or sister. According to Shona custom, these cattle are not paid in order to purchase the bride, but as a token of thanks to the parents of the bride for bringing up the daughter well. Marriage without roora is inconceivable. All children born of a marriage which has been contracted through roora belong to the husband, whether they are biologically his or not. He claims the children by virtue of the cattle he has paid.

The roora cattle are paid in different stages. A man announces his intention to marry a woman by sending a beast through a mediator to his prospective in-laws. After the acceptance of the first, a second beast is sent. This is slaughtered and the meat is consumed by both families together. The meat is considered to strengthen the bond of friendship between the two families. The elders welcome this occasion to summon their ancestral spirits to bless the prospective couple. After the ceremony between seven and fifteen head of cattle are given as part of the marriage. When this is accomplished, the parents of the bride escort their daughter to her husband. A beast is slaughtered by the groom's parents to welcome the bride into her new home. Before the couple meet sexually for the first time, the bride is giving a beast by the groom. This beast is hers, and she may pass it on to her children.

Cattle are also used at ceremonies – births, fertility rites, weddings and funerals. When a child is born, one beast is slaughtered to feed the mother and the godmother and another is given to the child if he is a son. This is an occasion marked by eating meat and drinking beer.

Cattle are used at fertility rites. When the crops are about to ripen young heifers are slaughtered to enhance the productivity of the crops. When the newly-married couple fail to produce children a young beast is slaughtered. Its meat is mixed with certain herbs and this mixtures is given to the couple to eat to make them productive.

At wedding feasts, cattle are slaughtered. This is essential in making the feast a success in the eyes of the community and, at the same time, ancestral spirits are summoned to bless the couple. On a certain occasion, a man may invite his blood relatives and slaughter a beast and at the same time summon the ancestral spirits to bless the entire family.

When an adult member of the family dies, a beast is slaughtered and the meat is consumed by the people who attend a funeral. This beast is believed to accompany the deceased into the next world. Later, a rite is performed to call back the spirit of the deceased. At this ceremony a beast is slaughtered. Amid much drinking and eating another beast is brought in and given the name of the deceased. If the deceased was a man, he is given a bull, if a woman she is given a cow. If this beast is sold or slaughtered, a replacement is found. If it has been determined that the cause of an illness or death in the family can be attributed to the displeasure of an ancestor, a beast is offered to appease the spirit of that ancestor. The beast is left alive or slaughtered and a rite is performed appealing to the spirit of the ancestor and at the same time reprimanding it to remove the sickness or prevent the recurrence of such deaths. The beast is the liaison between the living and the dead members of a family. If the beast is kept alive, it is regarded as that ancestor incarnate and must be reverenced.

Cattle also used to settle debts, disputes and civil or criminal cases. If one fatally injures a neighbour he makes reparation in the form of cattle to the survivors of the deceased. If one commits adultery with the neighbour’s wife the plaintiff may demand cattle as damages.

Cattle are used as a source of food only in the supply of milk which is preferred sour. Meat is obtained only when a beast dies or is killed for ceremonial purposes. Cattle may be exchanged for grain in times of famine.

In Shona society, cattle have more social than economic value.

Reference

Clive and Peggy Kileff (Editors) E. Lee (illustrations) Shona Customs. Mambo Press in association with the Rhodesia Literature Bureau, Gwelo, 1974