Angwa (Ongoe) – Afro-Portuguese Feira sites in Mashonaland West

Introduction

In August 1945, the same month that the United States dropped the first atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, Mrs Elizabeth Goodall made the journey up to the Angwa river between Sinoia (present-day Chinhoyi) and Karoi. Mr. H. B. Maufe, the first director of the Geological Survey of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) from 1910 – 1934 had returned to then Rhodesia during the war years as there was a severe shortage of staff and after he had visited the Angwa river in 1941 had prepared a short report on two of the Portuguese ‘forts’ which were visited.

Elizabeth Goodall’s visit was at the request of the Commission for the Preservation of Historical Monuments, to carry out an inspection of these reported Portuguese “forts” and establish if they actually existed and if they were Portuguese in origin and if they should be proclaimed National Monuments. Her report covers four of the ‘forts.’ Two others were brought to her attention at the time, but were not visited, and as far as I know, details have never been published about them.

The Portuguese settlements along the Angwa river were known by Portuguese seventeenth century writers as Ongoe, a word clearly phonetically derived from Angwa.

Other fiera sites on the northern Mashonaland Plateau described on this website include Dambarare, Massapa, Maramuca (Rimuka) Luanze (Ruhanje) The first two are included under Mashonaland Central, the third under Mashonaland West and the last under Mashonaland East.

Portuguese trading settlements are not always feiras

I have substituted ‘feira’ for ‘fort’ throughout in the belief these were trading settlements permanently lived in by Portuguese traders or their vashambadzi[i] and unfortified. It is clear that both Swahili traders and the Portuguese or their vashambadzi visited local people to buy gold as De Barros writes: “the Moors who carry on the trade among them make use of artifice to arouse their cupidity, for they cover them and their wives with clothes, beads and trinkets, with which they are delighted, and after they have thus pleased them, they give them all these things on credit, telling them to go and dig for gold and if they return in a certain time they can pay them for all.”[ii]

However it is necessary to highlight that not all trading settlements between local people and the Portuguese were designated feiras. According to the Portuguese, a feira is only recognised as such when a document, Regimento, establishes it through the appointment of a Captain or similar officially-appointed officer. So the trading establishments on the Angwa River would not have been regarded as feiras until the Captain of Mozambique Island appointed or recognised the first Portuguese Captain. However, I shall refer to them as feiras as they were established as permanent market places and although they had rudimentary bastions, were clearly not forts.

From 1684 the Portuguese traders flee to Tete

There appears to be no evidence of when the Angwa feiras were established, but in 1684 João de Sigueira was sent by Caetano de Melo de Castro[iii] to reinforce the feiras on the Angwa river in anticipation of an attack by the Rozvi under Changamire Dombo and the bastions were most probably added to feiras 2, 3 and 4 at this time.

In June 1684 the Rozvi met the Portuguese at the battle of Maungwe so the addition of the bastions to the Angwa feiras at this time makes sense. Maungwe was the beginning of the end for the Portuguese on the Northern Mashonaland Plateau. The Rozvi forces had many more warriors then the Portuguese and their auxiliaries, but the Portuguese arquebuses had superior firepower and at the end of the first days fighting the Changamire had ordered his forces to retreat. However during the night the Changamire ordered women to pile brushwood around the Portuguese lines and at dawn great fires began burning around the Portuguese camp. This led the auxiliaries to panic and the outnumbered Portuguese made a withdrawal to Macequece leaving the Rozvi the victors.

Most of the few dozen Portuguese traders and their families left at this time for the safety of Tete leaving the so-called Canarins at the feiras. The Canarins were Konkani people from Goa and were commonly Christian Indians. Ellert states that they built good trade relations with the Africans and some had experience at gold mining from India, so that gold production actually increased at Angwa and Chitomborwizi.

Intensive artisanal gold panning and commercial mining on the Angwa river

There has been gold panning on the Angwa river for many centuries – probably Swahili traders traded at established gold buying market-places in the Makonde district (formerly Lomagundi) long before the Portuguese arrived in the 16th Century. The Angwa river has always been a magnet for gold prospectors and members of the Pioneer Column and demobbed British South Africa Company Police formed syndicates and headed for the area in late 1890 to stake the gold claims to which they were entitled.

However the destruction caused by gold panners in recent years has been at a level never before experienced and as a result the Angwa river and its banks have suffered enormous damage that may be irreversible and have long-lasting consequences for the environment.

Unfortunately illegal fossicking has also damaged the feiras described below. At this time it is probably too late for meaningful archaeological excavations to take place as the sites will have become too disturbed and irretrievably damaged.

Historical references to the Angwa feiras

Henk Ellert[iv] writes that Father Filipe de Assunção spent fourteen years on the Northern Mashonaland Plateau and wrote that the Ongoe feiras were three days journey from Dambarare.[v]

Ellert also quotes Francisco de Sousa in his Oriente Conquistado of 1697 as saying they are four days travel and were noted for their fine gold.

Ellert adds that after the Rozvi invasions and sacking of Dambarare in 1693 most of the Portuguese garrison and traders withdrew from the Mutapa State, but “some hardy Indians remained including Domingos Carvalho who was a relative of Manuel Pires Saro, Capitão-mor of the Portuguese garrisoned at Mutapa in the Zambesi Valley.” They were most likely Marathi-Konkani Indians from Goa.[vi]

Friar António da Conceição wrote: “The Portuguese settlers had frequently fought wars in the interior, but they were taken by surprise when Changamire attacked the fairs and destroyed them in 1695. Although they attempted to rally reinforcements, as they had on many previous occasions, they were unable to recover the land they had lost and by the eighteenth century were restricted to the Zambesi Valley and to the areas around Sofala and Quelimane, successive rulers of Butua refusing to allow them to re-establish the fairs in the interior.”[vii]

Malyn Newitt adds ‘The destruction of Dambarare therefore, was a decisive moment in the history of central Africa. Although the Portuguese continued to trade with the peoples of the plateau, using the fair at Manica and a newly established fair at Zumbo near the confluence of the Zambesi and the Luangwa, they now turned their attention to expansion north of the river and to exploiting the gold diggings that were discovered along the northern escarpment.’

Ellert quotes Friar António da Conceição as writing that Domingos Carvalho developed a successful local trade on the Angwa river with a local Mashona chief trading cloth in exchange for silver. He says the Mashona were careful not to disclose the source of the metal, but that “a canny Portuguese Indian allegedly discovered the source of the silver lode. He secretly obtained samples of the ore which were sent to Jose de Fonseca Coutinho who was then Lieutenant-General of the Rivers. Part of this silver was melted down and reportedly wrought into a chalice for the Sena Cathedral.”[viii]

This may simply be a local version of the story of the Belém Monstrance.[ix]

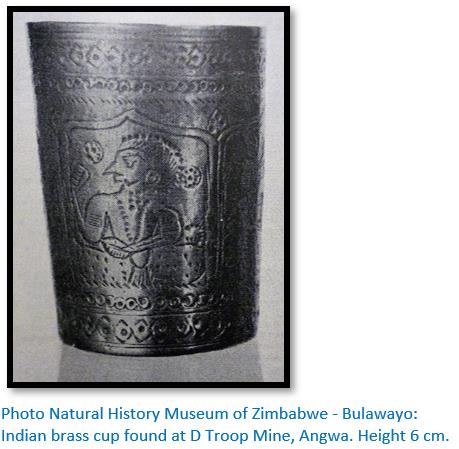

Like Ellert, I am sceptical of this claim for silver – readers of the three articles on The Mutapa state (under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) will know that the Portuguese were seemingly obsessed in their unsuccessful quest for the silver mines of Chikova. Copper and gold have been found quite extensively in the Makonde district (formerly Lomagundi) Roger Summers lists the Angwa river in area 13 for Piriwiri and states that K.R. Robinson found Chinese ceramics, an iron spearhead and an iron gad[x] on the Angwa river in 1919. Another eleven pre-European ‘ancient workings’ are listed in the immediate area – most were for copper, but gold is also listed. D Troop of the British South Africa Company Police who were demobbed and formed a syndicate on the Angwa river found an Indian brass cup from the 14-15th Century 40 ft (12 metres) down an ‘ancient working.’[xi]

Ellert writes that these Angwa feiras may well have been occupied by Portuguese or Goan traders well into the 18th century.[xii]

Prospectors reports on the Angwa river Portuguese trading settlements

Early British South Africa Company reports state the Crescent Copper Claims had pre-European ‘ancient workings’ that were 900 x 60 x 60 ft (274 x 18 x 18 metres) and contained very old timbering.[xiii]

William Harvey “Curio” Brown gives an account of a six-week hunt in September 1892 when he established his main camp near the Chinhoyi Caves before starting for the Angwa River. On the way he met two cockney prospectors, fresh from London, who had killed their first rhinoceros the day before. On sighting the beast they took it to be a “helephant” and both fired, one lucky shot killing it so the animal rolled onto its back with its feet sticking up. As they approached, one cried out: “it’s no helephant, it’s a wagon turned upside down.” “G’wan Bill” said the other, “it’s a rhinostrich!”

Brown met up with Arthur and Herbert Eyre who have shot one of the last white rhinoceros and were preserving the skin and skeleton as a museum specimen for the Cape Town museum. They captured a rhino calf alive, but it soon died. The party comprising the Arthur and Herbert Eyre, Brown and thirty-two carriers travelled together and named a stream Lemon Creek on account of the large lemon trees growing on its banks, a leftover of the Portuguese, now known as Piringani or Ditchwe.

On the Angwa River they find alluvial gold workings extended for miles: “ancient placer diggings were numerous there and in fact many miles of both banks of the river had been turned over for alluvial gold, some of the excavations being of tremendous size.” Near their camp site are what they assume to be the remains of an old fort (450 square feet) presumably Portuguese as it is built in European style. A deep trench had been cut on three sides, the south side bordered by the ancient river-bed. At two corners are large heaps of earth, apparently bastions for mounting cannon and another mound at the centre of the fort, the remains of an adobe brick building, around this had been built an adobe wall with small corner towers. Brown guesses it has been built to protect the gold mines and although the structure only looks to be fifty years old, from the size of the trees growing in the ruins he guesses it to be one hundred and fifty years old or more. On the neighbouring hills are the remains of what he believes to be the residences of the mine owners.

The Angwa gold trade has been a seasonal occupation for centuries

I have already shown above that alluvial gold panning remains an important activity even today. Ian Phimister writes that the main focus of the gold trade in the nineteenth century was Tete and, to a lesser extent, other Portuguese settlements on the Zambesi. It was not unusual for individual expeditions to collect as much as twenty or thirty pounds (9 – 14 kg) weight of gold. Other traders operated on a much more modest scale, sometimes sending only a single African to the alluvial areas. The total trade goods carried in one instance were ‘five guns, ten pieces of limbo, a bag of salt and some caps and powder.’ Weights and a balance completed the equipment, because as one African explained, “sometimes people say a quill is full when it is not. I had three weights, they were all the same weight. They had holes in them. The one with four holes in it is the weight of gold worth a gun.”

An alternative way of conducting the gold trade was for Africans themselves to travel from the gold washing areas to the Portuguese trading stations on the Zambesi. The gold carried was stored in porcupine or guinea-fowl quills and sometimes in reeds, the ends of which were stopped with small pieces of bark. From the Mrewa area gold was taken to the Portuguese settlements normally by following the Luia river until it joined the Zambesi close to Tete. Gold washed on the upper Angwa river was taken to the Portuguese usually by groups of two or three people usually along a route via Sipolilo and then through the Dande region to Kanyemba. The estimated time for the journey there and back was approximately six weeks. This elimination of the middleman was of added importance in the 19th century when both the absolute and relative volume of the gold was declining as alluvial deposits were depleted and the ivory trade grew in importance.[xiv] [xv]

Description of the Feiras on the west bank of the Angwa river

Feira No 1 (1729 BB 2) 17°03’55.71”S 29°56’49.24”E

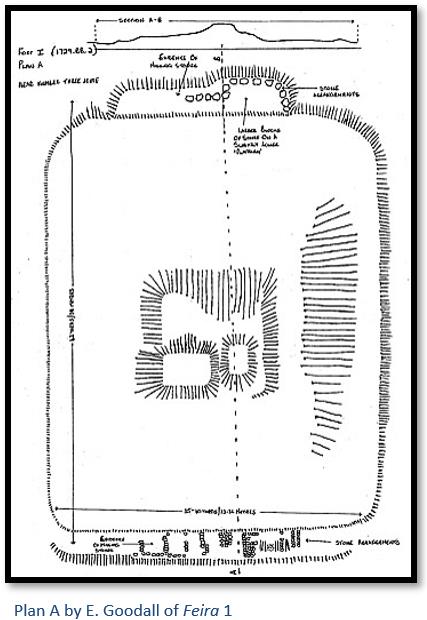

This feira is situated near the west bank of the Angwa river, close to the site of the Number Three Mine, on Upson Downs Farm and is close to the old homestead and mine. Mrs Goodall states at first viewing there was nothing striking about the site and it appeared doubtful whether it was a feira.

But she writes the general plan showed features similar to the other feiras and so was recorded and general measurements taken. The whole extent was not clear, the length being 42 yards (38 metres) the width approximately 35 to 40 yards (32 to 36 metres)

The central mound, which appears in all the Angwa feira sites and is most probably the store rooms and dwelling building, it is very irregular, but the general lay-out was originally planned as a rectangle. Goodall said in her report that only excavation work at the central mound would reveal if this elevation was an anthill, or building. Unusual features, not observed at feiras 2-4, were certain stone arrangements on the two shorter sides. She believed the stones had been placed in a geometrical way along the upper side by human hands; towards the one corner are signs that stones have been removed. She believed further research work might reveal if these stones might be graves.

She observed at the opposite side of the enclosure were some larger blocks of stone on a slightly lower “platform” that looked like they had been arranged in a geometrical position.

She believed that this feira was in an isolated location and therefore unlikely to be disturbed. Her recommendation was that it required further investigation by an archaeologist field-worker but until then she doubted whether it deserved the status of a National Monument.

Chris Dunbar visited feira 1 which he writes[xvi] took a long time to find: “when I did find it I was surprised that it was not damaged in any way just over grown with excessive grass and trees.”

Feira No 2 (1729 BB 5) 17°03’38.50”S 29°58’04.58”E

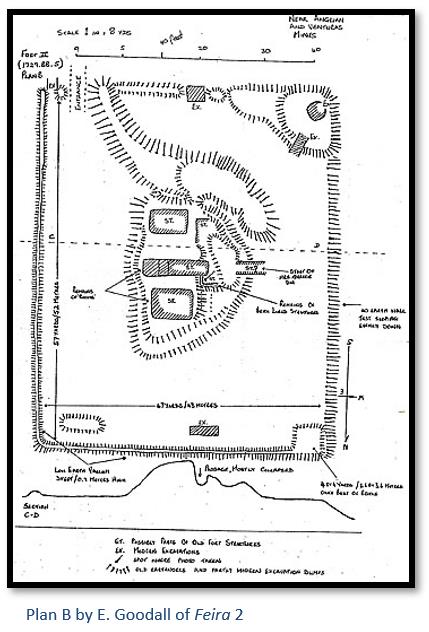

This feira is also on Upson Downs Farm, not very far from feira 1 and nearer the Angwa river on open ground. A tree was growing out of the centre mound and forms a landmark from a distance. Plan B shows that much unauthorised excavation has taken place at the site resulting in the destruction of important features.

The feira is a rectangular enclosure of about 57 x 47 yards (52 x 43 metres) The East and North sides are protected by a low earth vallum,[xvii] whose greatest height and width is 3 feet (90 cm), but in most places is much less. The southern boundary is much obscured by a large earth pile, which is highest in the South – West corner. Several modern excavations and an “entrance” have been made near the south east corner. There is no earth wall on the west side of the enclosure where the ground slopes evenly down into the surrounding countryside.

Clearly the rectangular enclosure and its various earthworks are man-made, and all the earth enclosed in the rectangle has been carried there. Grass fires had recently burnt and fresh grass was growing outside the enclosure, but within the enclosure very little grass was to be seen.

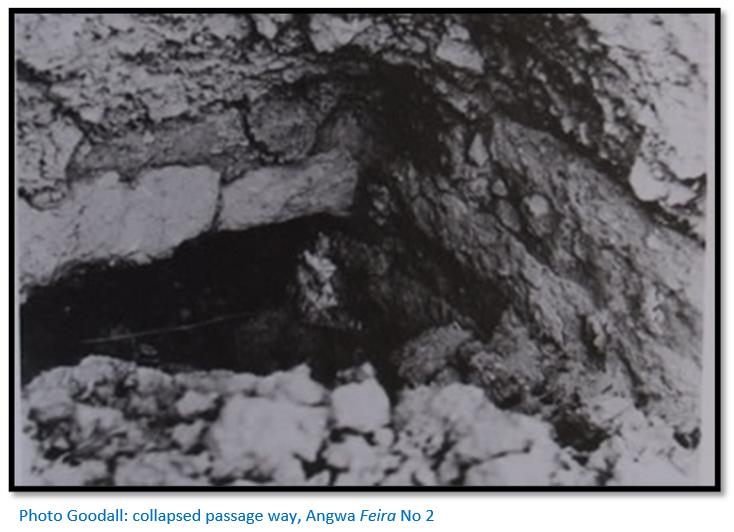

The centre mound is about 9 - 10 feet (2.7 – 3 metres) above the inner level of the fiera, though very irregular and roughly oblong. It shows many signs of disturbance, due to recent prospectors looking for ‘treasure.’ Large holes are seen in the central mound and according to Mrs Goodall’s guide, the remains of two or three rooms were found within the central mound and a passage along which he said he had walked when a little boy. Mrs Goodall was initially inclined not to really believe this statement from her guide.

However on a closer inspection she saw that the central mound indeed contains an inner structure, built of sun dried, oblong bricks, so–called ‘Kimberley bricks’ similar to those used at Dambarare and Maramuka (Rimuka) She believed this was a passage corner, which must have quite recently collapsed, as it showed two newly exposed inner surfaces. She saw sun-dried bricks of 1 foot (30 cm) 1½ foot (45 cm) and 2 feet (60 cm) lengths. Above the walls was an earth layer of about 2 feet (60 cm) Two large holes which may originally have been rooms showed no signs of how they were constructed. They were from 6 - 7 feet (1.8 - 2.1 metres) in depth. Near the upper end, one of the holes has a row of stones along the two longer sides.

Mrs Goodall was told Mrs Quarrie was responsible for most of the fossicking and destruction at this feira and visited this lady now residing at Ardbennie in Salisbury (Harare) to obtain further information. She was still fit, although some of her statements were somewhat confused, but she learned the following.

Mrs Quarrie and her husband lived in the Angwa valley about 25 to 30 years ago. They worked the Mum’s Reef Mine, which is about 2 - 3 miles (3 -5 km) from this feira. Her son reported one day having seen a curious square ‘anthill’ out of which a big tree was growing. Mrs Quarrie realised that this could not be an anthill and instructed her servants to excavate in various places, concentrating on the central mound.

They dug into a wall about 3 feet (90 cm) thick, made of ‘Kimberley bricks.’ A ‘stoep’ (i.e. verandah) was found running alongside the wall, and then a second wall running parallel with the first. A hole was dug into this wall which led into one of the chambers. This haphazard digging (fossicking) would have destroyed much of archaeological significance, but here was found a lot of blue and white hand-painted china and also some iron arrow heads. These were removed by Mrs Quarrie and subsequently lost. Excavated earth was removed by wheelbarrow. Mrs Quarrie did not know how much earth was moved, or what was destroyed, but she observed that the square north west corner (4 x 4 yards) (3.6 x 3.6 metres), was built entirely of ‘Kimberley bricks.’ Mrs Quarrie added that the whole rectangular ‘yard’ was paved with these Kimberley bricks that were so heavy that it was almost impossible to lift them.

Another prospector and miner, Mr Paré who formerly mined the Go–Ho claims at the Angwa river replied in a letter dated 11 November 1945 to Mrs Goodall’s requests regarding the feira remains. He wrote he did no fossicking at the feira sites himself, but he observed Mrs Quarrie digging at the central mound in the mid-1920’s and saw the exposed passage and room. The open room appeared to be lined with ‘Kimberley’ sun-dried bricks – an adjoining room was visible through a hole in the wall with bricked sides and appeared to be in excellent condition.

Although probably extensively ruined, part of the original structures are intact and Mrs Goodall thought feira 2 should be carefully excavated by a field-worker and protected if possible to prevent any further diggings by unauthorised persons. The earth covering the central mound should be carefully removed to establish what remained below.

Mr Paré was asked about rumours of chain-mail armour being found, but stated he had not seen any, nor were any human burials observed. He had collected numerous copper beads, but these were found whilst gold-panning in the Angwa river and were most probably worn by local Mashona. He sent two examples of copper beads with his letter.

The only surface find by Mrs Goodall at feira 2 was part of the top of a wheel-turned water flask made of fine grained light brown earthenware that are known to come from Portuguese factories.

Description of the Feiras on the east bank of the Angwa river

Although physically close to those feiras on the west bank in 1945 it was not possible to cross the Angwa river in those days and Mrs Goodall had to go back towards Sinoia (Chinhoyi) before turning off and following the road through Two Tree Hill Farm and Two Tree Hill Extension No. 1 and 2, that were both unoccupied to the camp of Mr A.M. Martin. She writes that Mr. Martin was the oldest surviving resident of the 1890-91 Angwa river goldrush and was most helpful as her guide.

Feira No 3 (1729 BB 1) 17°01’52.97”S 29°57’47.89”E

Feiras No 3 and 4 were those described by Mr Maufe in his short report, presumably they were shown to him as he carried out his geological survey of the area.

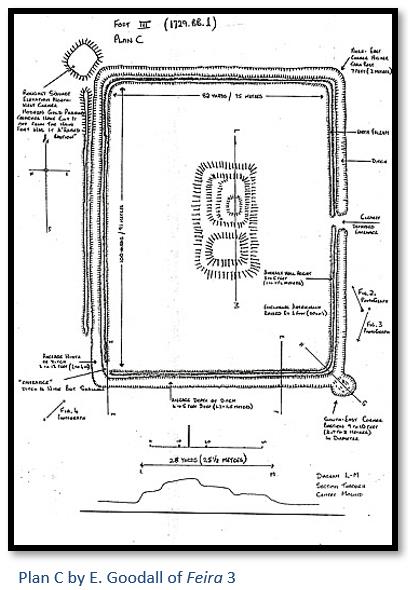

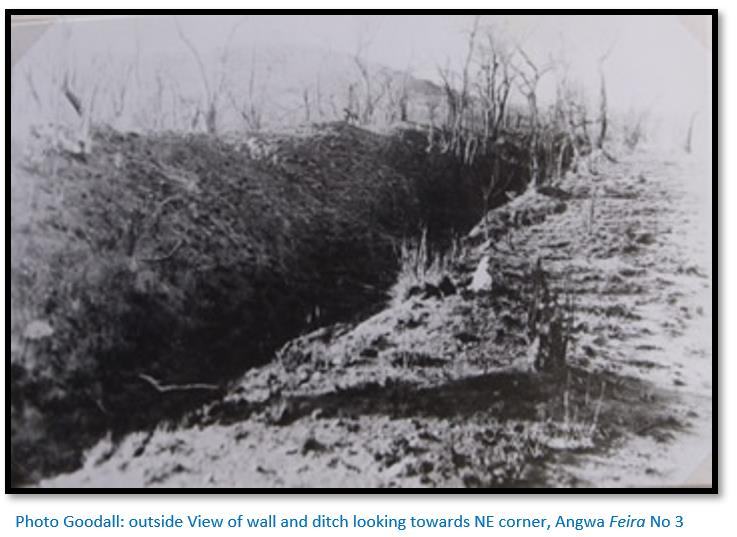

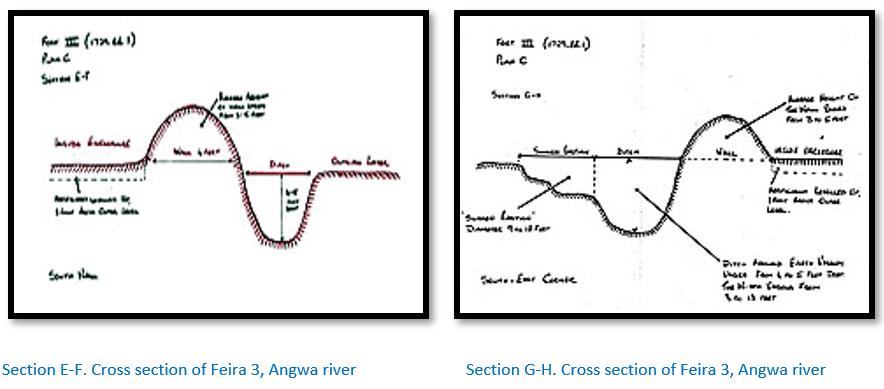

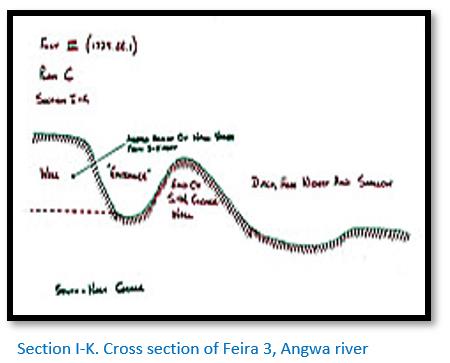

Feira No 3 was the largest and most impressive of the four feiras visited by Mrs Goodall. It was designated National Monument No 70 and is situated on Two Tree Farm.[xviii] The inner measurements of the rectangular enclosure are approximately 100 yards long x 82 yards wide (91 x 75 metres) The enclosure is protected on all four sides by an earth embankment outside which there is a parallel ditch. See Section E – F. The depth of this ditch is up to 4 - 5 feet (1.2 - 1.5 metres) and the width varies from 3 - 13 feet (1 - 4 metres)

On the west side, parallel with the Angwa river, is an additional outer wall and from here the ground slopes down to the river. The average height of this wall is from 3 - 5 feet (1 - 1.5 metres) above the interior of the enclosure. The ground inside the enclosure is approximately a foot (30 cm) above the outer level and has apparently been artificially levelled up.

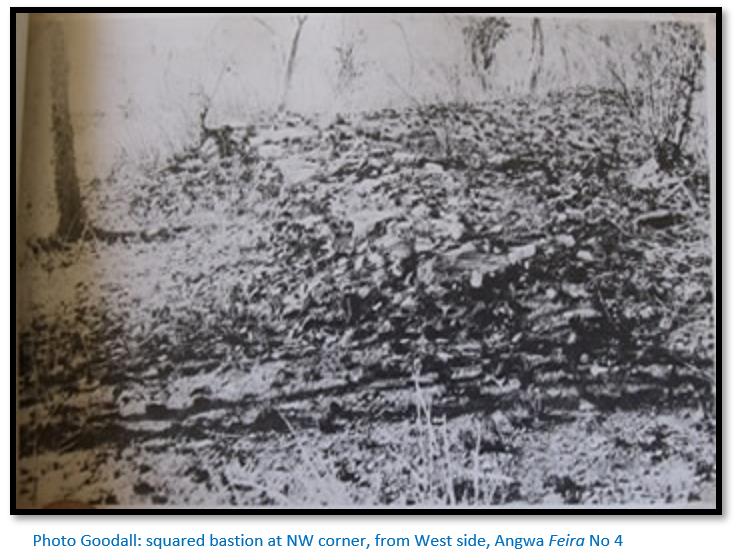

The whole western enclosure wall and particularly at the north west corner has been damaged by digging by unauthorised persons. There is a roughly square raised structure at the north west corner which must have been an important part of the enclosure. Deep trenches have been dug across it and cut it from the main enclosure. The illegal diggings and cross trenches make access difficult to assess how the original structure looked.

The north east corner is raised above the adjoining walls being approximately 7 feet (2 metres)

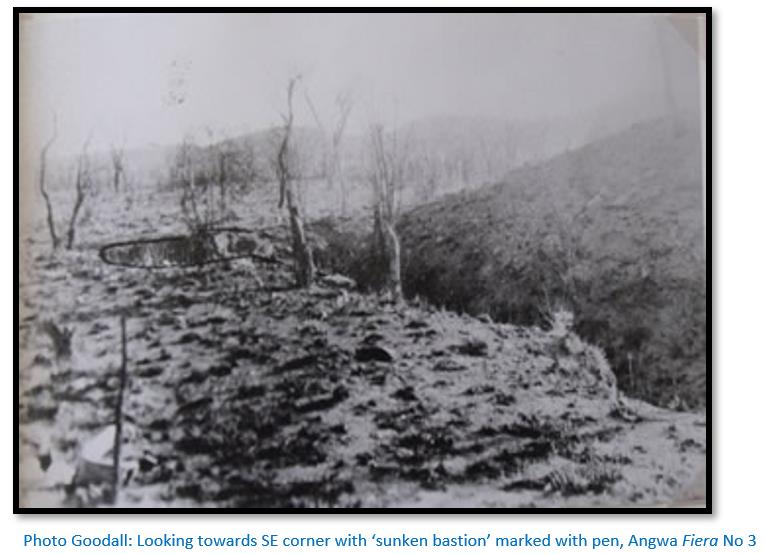

At the south east corner of the enclosure is a feature that resembles a circular sunken bastion with a diameter of 9 x 10 feet (2.7 x 3 metres). See also Section G-H

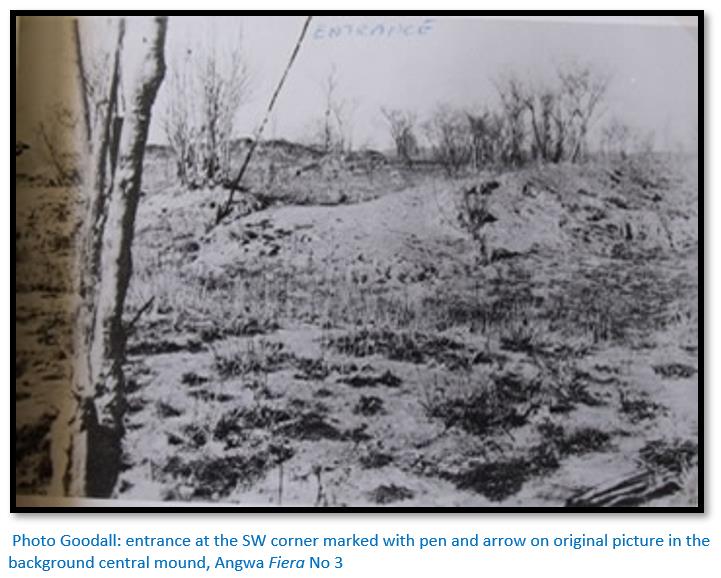

There appears to be an entrance at the south west corner, where the ditch is wide but very shallow. The entrance is quite level. See the photo below and Section I – K.

There appears to be another entrance in the approximate centre of the east enclosure wall.

The centre mound is very irregular in shape and has been damaged by digging by unauthorised persons which makes it difficult to judge the original height.

The only find from outside the enclosure was one shard of glazed earthenware, part of the round bottom of a large jar. A similar piece was given to Mrs Goodall by Mr Martin, found by him many years ago, it is a part of the hexagonal bottom of a large jar.

Feira No 4. (1729. BB. 19) 17°01’43.58”S 29°58’19.88”E

This is located near the north eastern boundary of the Farm Two Tree Hill Extension No 2.

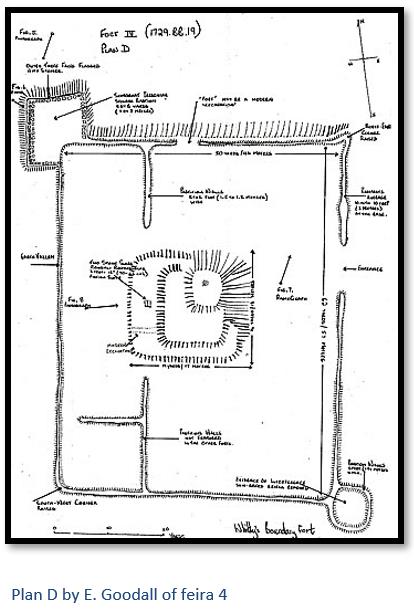

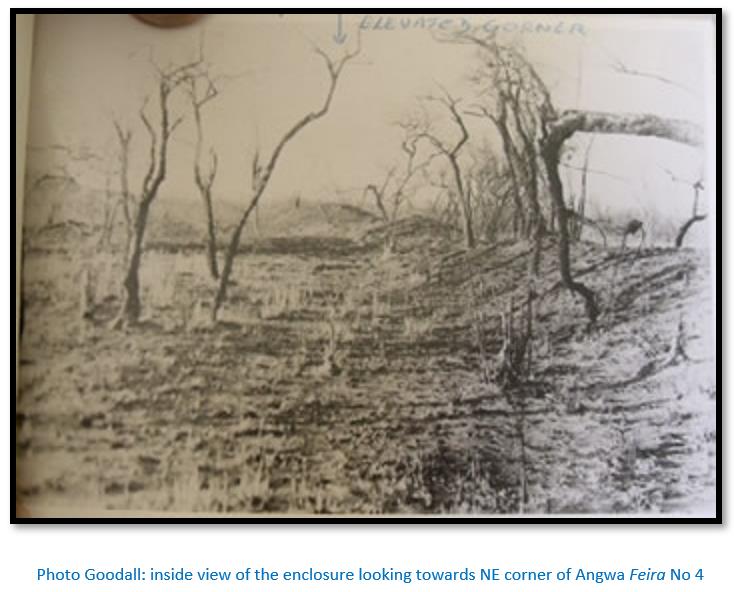

The enclosure is 62 yards long x 50 yards wide (57 x 46 metres) See Plan D.

The feira outline consists of a rectangular enclosure, bounded by an earth bank on all four sides. The main entrance seems to have been at the approximate centre of the east enclosure wall. There is another smaller entrance in the centre of the north wall, but this maybe the result of digging by unauthorised persons. The enclosure banks have an average width of 10 feet (3 metres) at the base.

The partition walls shown in the diagram are 5 - 6 feet (1.5 - 1.8 metres) wide at the base and are a feature not observed in the other feiras.

The north west corner has a structure resembling a square bastion, somewhat irregular in shape, but approximately 8 x 8 yards (7 x 7 metres) The three outer faces are flagged with stones. Both bastions may have been added some time after the original earthwork was constructed.

The South West and North East corners are a little higher than their two adjoining walls.

The south east corner also has a structure resembling a bastion, however all that remains is an irregularly round earth wall, enclosing a platform a little higher than the level within the enclosure. The walls are 5 feet (1½ metres) in width at the base and lower than this in height, but it is very likely that digging by unauthorised persons has reduced their height. In places it looked as though the original sun-dried bricks had been removed.

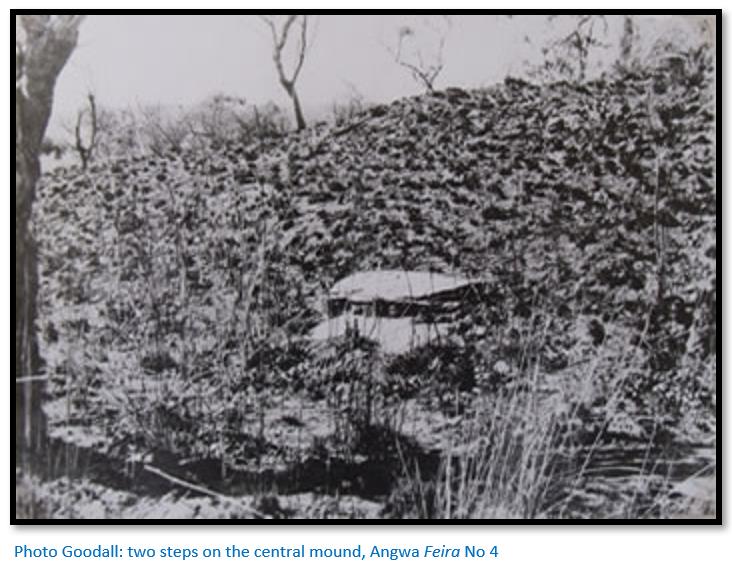

The centre mound (14 x 19 metres) is badly damaged through 20th century fossicking for ‘treasure.’ Two stone slabs, roughly shaped to a rectangular size, 3 x 1.5 feet wide (90 cm x 46 cm) of a pinkish slate may have served as steps from a low platform to the upper one.

According to Mr Martin, a prospector dug to the right of the steps and came across a chamber, but no remains of this are now visible, although it may be hidden under the present mass of earth. The central mound is approximately 14 x 19 yards (13 x 17 metres) in size.

Mention of further Feiras not visited (1729 BB 3) 17°00’30.58”S 29°59’43.52”E

Whilst recording feira No 2 Mrs Goodall’s guide said there was another ‘Portuguese fort’ very similar located higher up in the nearby hills, but this fifth structure was not visited.

Mr Martin mentioned there was a sixth Portuguese structure in the Angwa valley, about 10 - 12 miles (16 - 19 km) north-north-east from his camp alongside a small river but could give no further details. Mrs Goodall observed it may have been undisturbed by fossickers and should be searched for by a field worker.

Mr Paré remembered similar structures near Mt. Darwin and Makaha. Mr McGregor, of the Geological Survey, has seen one structure at Makaha that he says is exactly similar to Plan ‘D’ of feira No 4.

After Chris Dunbar visited the site he wrote: “The area has been seriously over run by illegal gold panners and they have caused extensive damage to Angwa Fort 4.”[xix]

Mrs Goodall’s general observations in her report

(1) Mrs Goodall recommended follow-up investigations of feiras 2,3 and 4 although their original structures have been substantially damaged by fossickers. They warranted protection from further fossicking and she believed local people should be warned not to excavate. Any work by an authorised field worker would require that skilled excavators are brought to site as there was no labour to be obtained in the vicinity of the Angwa river. The only people resident in the area were a few isolated miners and their native workers.

(2) Mrs Goodall believed all four enclosures were Portuguese in origin and connected with the gold trade on the Angwa river. Each of the four structures featured a rectangular plan, three had walls which meet at right angles and were re-enforced with bastions at the corners. Each also featured a central mound under which there was evidence and observations of bricked walls and ‘rooms’ under the earth masses that currently cover them. The constructions showed evidence they were built by people who practised a masonry tradition.

(3) Mrs Goodall believed further archaeological finds would probably come to light with a fuller and careful examination of the structures.

Portuguese occupation at the feiras

The Portuguese feiras of Ongoe (Axelson, 1960) appear to have enjoyed a brief period of prosperity in the early 1690’s before being abandoned before Rozvi invasions of Changamire Dombo and appear to be one of the few sites to be reoccupied in the early eighteenth century.

Comparison of the Angwa (Ongoe) feiras with those at Luanze (Ruhanje) and Maramuca (Rimuka)

There are definite parallels between the four enclosures structures described above on the Angwa river and those at Luanze and Maramuca that include:

(1) They all have straight rectangular earthwork banks forming an enclosure. The lengths and widths vary and some of the larger enclosures have a further bank and ditch.

(2) They all had a single central-sited building made from sun-dried bricks. Once abandoned by their residents the roof and wood superstructure are quickly attacked by ants and collapse. After centuries of decay these buildings become earth mounds and only excavation reveals rooms, passages and ‘Kimberley’ bricks.

(3) At the corners of the enclosures there are sometimes projecting bastions. There could be four bastions as at Maramuca (Rimuka) and Luanze (Ruhanje) or they might comprise two bastions from diagonally opposite corners of the earthwork as at the Angwa feiras.

(4) They usually have some archaeological evidence of Portuguese occupation on the surface in the form of sherds of Chinese or Persian porcelain and ceramics with blue and white colouring or chocolate glazed exterior from the late 17th to 18th seventeenth century period.

(5) Archaeological excavation usually yields trade beads. Beads and cloth were the principle items that were traded by the Portuguese with the local people for gold. De Couto in 1634, wrote: “They also take for this trade some small beads made of potters clay, some green and others blue and yellow, with which neckets are made. . .” Beads were being imported in quantity into the interior as trade goods at least by the mid-17th century and have been found at all the trading settlements.

(6) Robinson (1965) has described pottery from two sites in the Zambezi valley, Ruswingo wa Kasekete and Mutota’s Ruin. The former has been considered (Whitty, 1959) to be in part 17th century Portuguese.

References

C. Dunbar. Angwa: a Portuguese Settlement, Market (Feira) and Fort in Zimbabwe. https://www.colonialvoyage.com/angwa-portuguese-settlement-market-feira-...

E. Goodall. A Preliminary Report on Four Portuguese Forts in the Angwa Valley. Queen Victoria Museum, Salisbury, Rhodesia 1946

H. Ellert. Rivers of Gold. Mambo Press, Gweru, 1993

S.I.G. Mudenge. A Political History of Munhumutapa c.1400-1902. Zimbabwe Publishing House, Harare, 1988

I.R. Phimister. Alluvial Gold Mining and Trade in Nineteenth Century South Central Africa. The Journal of African History Vol. 15, No. 3 (1974), pp. 445-456

R. Summers. Ancient Mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia, 1969

Notes

[i] Vashambadzi were African intermediaries or middlemen and their families who traded on behalf of the Portuguese traders based at the larger feiras or at Tete and Sena.

[ii] Da Barros Da Asia

[iii] At the time Caetano de Melo de Castro was Captain-General of Sena, Sofala and Mozambique Island. He was later appointed a Governor-General in Brazil and from 1702-7 was Governor and Viceroy of Portuguese India

[iv] Rivers of Gold, P61

[v] The Angwa feiras are 114 km north west of Dambarare. By foot they would be further – approximately 40 km per day on footpaths seems very good going.

[vi] Goa at the time was an important overseas territory of the Portuguese Empire, then known as Portuguese India for about 450 years, until it was annexed by India in 1961.

[vii] M.D.D. Newitt (Editor) East Africa Volume 2, Taylor and Francis, 2017

[viii] Rivers of Gold, P61

[ix] From Wikipedia: The Belém Monstrance (Portuguese: Custódia de Belém) is the most famous gold and polychrome enamel work dated 1506 and attributed to the Portuguese goldsmith and playwright Gil Vicente, on a commission by King Manuel I for the Royal Chapel, and later left in the King's will to the Jeronimos Monastry in Belem, at the time an outskirt of Lisbon, whence it derives its name. Currently it is part of the collection of the National Museum of Ancient Art, in Lisbon.

Made in late Gothic style, it was fashioned of "1,500 mithqals of gold" brought from Vasco da Gama's second trip to India in 1502 as a tribute from the Sultan of Kilwa (in present-day Tanzania), a sign of vassalage to the crown of Portugal. The base is inscribed:

O. MVITO. ALTO. PRICIPE. E. PODEROSO. SEHOR. REI. DÕ. MANVEL. I. A. MDOV. FAZER. DO OVRO. I. DAS. PARIAS. DE. QILVA. AQVABOV. E. CCCCCVI translated as "The Most High Prince and Powerful Lord, King Dom Manuel I, ordered this to be made from the gold of the tributes from Kilwa. It was completed in 1506.

[x] Summers, P167. Where gold bearing ore could be cracked, either through fire-setting or because of its texture, an iron gad was used to split it. The types used by pre-European miners were pointed at both ends with one end held in a wooden handle made from a tree root.

[xi] Summers, P46

[xii] Rivers of Gold, P65

[xiii] Ibid

[xiv] Phimister, P450

[xv] Sipolilo is present-day Guruve

[xvi] Chris Dunbar article is on the website https://www.colonialvoyage.com/angwa-portuguese-settlement-market-feira-...

[xvii] The Roman word vallum usually refers to the palisade which runs along the along the outer wall of a fortification. In Mrs Goodall’s case, she is referring to the outer earth bank.

[xviii] Two Tree Farm appears to have been renamed Two Tree Hill Farm

[xix] See (i) above for details