The Newton Commission conclusions on the ‘Victoria incident’

Introduction

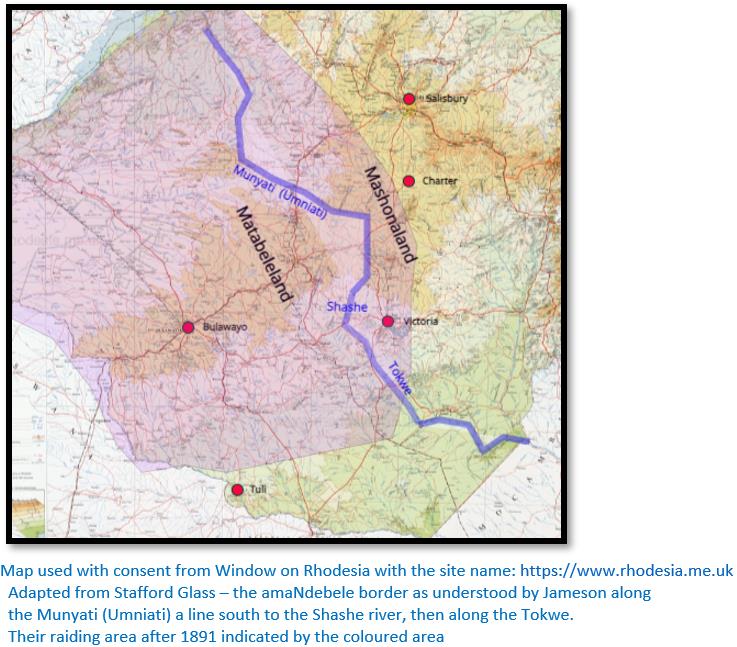

The events leading up to the ‘Victoria incident’ are included in the article Re-examining the events leading up to the “Victoria incident.” These included numerous instances of amaNdebele raiding of kraals north and south of Victoria (now Masvingo) and the harassment of travellers on the road between Tuli and Charter, as well as instances of ‘wire cutting’ of the telegraph line.

Clearly Lobengula had no intention of keeping his Majakas (young warrior-soldiers) on a leash and away from the Victoria district. On 11 June 1893 the inDuna of a small impi of about 70 men told Captain Lendy that they were collecting stolen cattle from Bere’s people and had strict instructions not to interfere with the settlers. Lendy states: “I answered that as it was an inter-tribal dispute it was not my business to interfere in the matter, but he must convey a letter from me to Mr Colenbrander to be interpreted to the King, in which I informed the latter of my coming up with the raiding party and the explanation the headman had given me. I added that it was as well for them that they had touched nothing belonging to the white men or we should otherwise have acted very differently and not allowed them to go so easily.”

The Mashonaland Times of 20 July 1893 in reviewing the ‘Victoria incident’ of 9 – 18 July said: “Lendy interviewed the marauders, who then informed him that it was Lobengula's intention to send a large impi to thoroughly wipe out the Makalangas, whom the King accused of crossing the Matabeleland border…and stealing cattle from outlying Matabele posts.”

Stafford Glass comments that Lendy was following Jameson’s policy; “flogging and arrest be meted out to the guilt Mashona; as usual, the gentle and tactful handling of the Matabele.”[i] To many settlers this policy showed the weakness of the chartered company’s policy of ‘cringing to the powerful.’

But as outlined in the article Re-examining the events leading up to the “Victoria incident there were few other options available to Jameson. The chartered company was in a weak financial position in 1892 so as long as the Majakas did not in any way disturb the white settlers, it seemed best to handle them sensitively.

Lobengula faced an increasing outcry from the Majakas to drive out the settlers. The loss of Mashonaland was now a fact to the amaNdebele, perhaps Lobengula felt he could regain his authority by permitting a large raid into the Victoria district.

Lobengula authorises a large raid, but gives full warning

James Dawson[ii] writes a letter dated 29 June 1893 on behalf of Lobengula in which he states an impi “at present” is leaving with the intention of: “punishing some of Lobengula’s people who have lately raided some of his own cattle.” Settlers are told: “it has nothing whatsoever to do with them” and “not to oppose it” and “if the people who have committed the offence have taken refuge among the white men. They are asked to give them up for punishment.”[iii]

The following day Johann Colenbrander[iv] writes three letters on behalf of Lobengula. To John Moffat he refers to the failure of the ‘small’ impi, met by Lendy: “The King has therefore decided to send a large force to punish Bere and others for their misdeeds (and I fancy that he will go for the recent wire cutters also)” but he stresses that Lobengula does not wish to cause a scare amongst the settlers and his majakas have been given: “strict orders not to annoy any whites they might meet” against whom “he has no hostile intentions.” The other letters to Lendy and Jameson contain much the same message. Dawson’s letter was taken by a runner who accompanied the impi to the Victoria district, Colenbrander’s letters were sent to Palapye for transmission by telegraph.

The big amaNdebele raid goes ahead

Clearly Lobengula was demonstrating his resolve to keep control over what he considered to be amaNdebele territory and his right to ignore the existence of the implied ‘border’ in the pursuit of those he considered had stolen cattle and carried out other offences.

Although he gave plenty of warning through the Dawson / Colenbrander letters, it was this impi’s actions that led to Jameson’s decision that he had to deal decisively with the amaNdebele question.

Events at Victoria on 9 July 1893

That Sunday morning Charles Vigers was out riding with Lt Percy Vipond Weir of the BSA Company Police approximately 5 km out of town when they saw a large number of Mashona streaming towards Victoria who told them the amaNdebele were raiding their kraals. They sought out the inDuna who: “said they were hunting Mashonas to kill them for stealing the King's cattle. He also told us there was a letter from the King with the main body.”

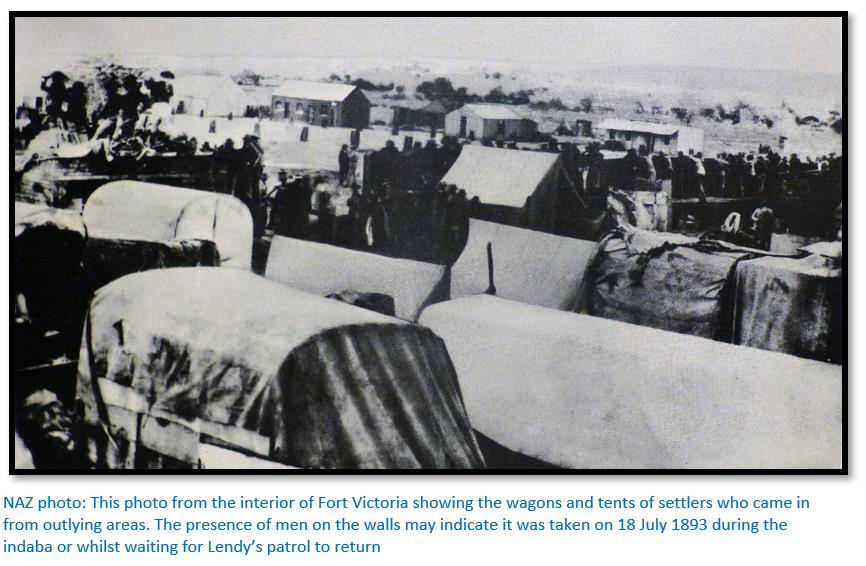

John Meikle in Victoria wrote: “I was lying in bed with a bad attack of fever. From early morning. I seemed to hear what appeared to be a hum of many voices and I could not think what it meant. It turned out that the noise was caused by hundreds of Mashonas coming in from outside for protection.” [Actually this event happened in the afternoon, but Meikle may have been confused with his fever and was writing in 1936] He goes on to say that the amaNdebele were killing any unfortunate Mashona they caught up with.

The Rev A.D. Sylvester, Anglican Minister at Fort Victoria, wrote soon after the event: “on Sunday, July the 9th about 3 o'clock in the afternoon whilst I was holding my Sunday school, I found my church and parsonage surrounded by an impi of Matabele, who were on all sides massacring the Mashona’s without mercy, simply out of thirst for blood.”

Vigers arrived back in Victoria just after the amaNdebele had assegai’d Mr Sylvester’s house servant to death: “I rode up to them and got off my horse and went up to a young Majaka who had a rifle. I snatched it out of his hand and asked him where he got it from. He said the King had given it to him. I told them that if they came any further they would be fired upon.”

Lobengula’s letter by Dawson which travelled with the impi was handed over the following day, 10 July when the inDuna Manyao arrived in Victoria with a dozen followers. The other letters to Lendy and Jameson were telegraphed from Palapye and arrived on the evening of 9 July.

Why did the Newton enquiry take place?

There had been controversy in the national and regional press after news of the ‘Victoria incident’ at Victoria in July 1893 reached Britain. Newspaper articles with letters and editorials from newspapers were sent to Sir Henry Loch, Governor of Cape Colony and High Commissioner for Southern Africa by Lord Ripon, then Secretary of State for the Colonies. The articles made a number of allegations about the conduct of the British South Africa Company and Captain Lendy, and Loch was ordered to investigate further by Ripon.

Mr Francis James Newton, Colonial Secretary of Bechuanaland (at the time a British Protectorate), was chosen to carry out the investigation.

Newton’s narrative in his report

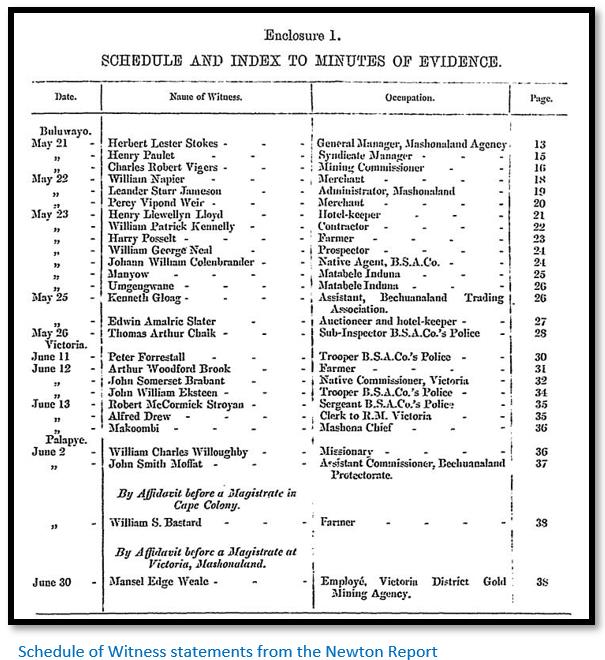

This article is taken from F.J. Newton’s[v] report on the incidents that took place in and near Fort Victoria between 9 July and 18 July 1893. Newton took evidence in the following year 1894 in Bulawayo on the 21, 22, 23 and 25 May, and in Fort Victoria on the 11, 12 and 13 June. Twenty-five witnesses appeared in person and two witnesses sent affidavits. The witnesses in person included Dr Jameson, two senior amaNdebele Indunas, and one Shona Chief. His report was published in August 1894.

Captain Charles Frederick Lendy

Captain Lendy at the time of the ‘Victoria incident’ was resident magistrate at the town and responsible for administration as well as judicial matters. He was in command of the patrol that were tasked by Dr Jameson on 18th July 1893 with seeing that the amaNdebele had ceased their raiding and were returning to Matabeleland. Lendy died on 13 January 1894 in Bulawayo – more than four months before the enquiry began.

Dr Jameson’s telegram to Sir Henry Loch reporting the ‘Victoria incident’

Dr Jameson, Victoria, to High Commissioner, Cape Town. 18th July. . . . The Indunas arrived after my last telegram. After some conversation, during which they would not consent to return beyond the border, I told them I would give them an hour to retire, and if they did not I would send my men to drive them out as I had informed the King. At the stated time Captain Lendy, with 38 mounted men, rode out, and found about 300 still on the commonage:[vi] these fired at Lendy’s party.[vii] Lendy then fired and pursued for about nine miles; a few men were killed, including two head-men. Lendy has now returned: no casualties. I believe the whole lot will now return to Matabeleland and further raiding cease. We are taking all due precautions in case of any returns, which I do not anticipate.

Newton’s Narrative from all the witness statements

I have changed some of the spellings to more contemporary usage and added paragraph headings to the narrative section of Newton’s report which is included below.

Sunday 9 July 1893 – amaNdebele impi raid on Victoria

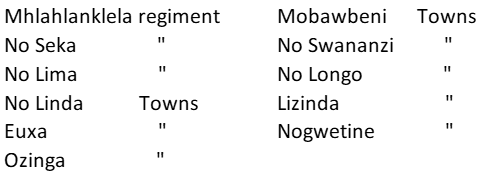

On the afternoon of Sunday the 9th July, that part of Mashonaland surrounding Victoria was overrun by a large force of Matabeles.[viii] I am in a position to give what I believe to be a fairly accurate estimate of the numbers of that force from the evidence supplied by Manyao,[ix] the Matabele Induna in command of it, who appeared before me at Bulawayo on the 23rd May. It consisted of three Matabele regiments, the Mhlahlandhlela, the HBuka, and the E’Sima, and the fighting forces of eight towns— N’Sinda, Euxa, Oyinga, Mobanbeni, H’Singo, H’Swananyc, Sizinda, and H’Gwetiwe, besides a lot of stragglers from the Maholi (serfs) belonging to those towns. About 2,500 Majakas left Bulawayo, and the Maholi[x] picked up on the way were about 1,000 in number.

As to the proceedings of this Matabele impi in the neighbourhood of Victoria up to the 18th July there is and can be no question.[xi] The whole country swarmed with them. The Mashonas had fled—some to their kopjes, where they were besieged, some into Victoria, and others far away - westward. Many of the men were barbarously murdered —stabbed and mutilated. It is unnecessary for me to discuss to what extent these barbarities were defensible from the Matabele point of view, but it is impossible to ignore the feeling of indignation and disgust which was felt by the inhabitants of Victoria and the district at the indiscriminate slaughter by the Matabele of the Mashona men and the abduction of the Mashona women and girls.

Lobengula ignores the ‘border’ agreed with Dr Jameson

It may be perhaps urged that Lobengula’s impi was acting technically within Lobengula’s rights; as the facts cannot be gainsaid, it appears to me the only point that can be urged on behalf of the Matabele. But there can be no doubt the Matabele exceeded any so-called right of Lobengula to harry the Mashonas. The impi was directed to proceed against Zimuntu and Bere (Mashona Chiefs), who were known to have assisted white settlers of the district by furnishing them with grain and labour.[xii] But the Induna Manyao had little or no control over the younger and headstrong Majakas, or over the troops of Maholi (serfs) who had followed promiscuously from the towns on the road from Bulawayo to join in the raid. The whole country north-east and south of Victoria was scoured by them.

Settler farms around Victoria are robbed and Mashona servants killed

Mr Willoughby, in his letter of the 16th October to the Daily Chronicle throws some doubt on a statement that one English farmstead was raided, as no report had reached him to that effect other than the official report quoted by him. I gather from the evidence, and am quite satisfied, that several English farmsteads were raided. By “raiding” I mean that the Matabele came upon these farms, stayed there, chased the herds, killed all the Mashona servants they could catch, and appropriated all the cattle they could find, without inquiring whether they were the property of Mashonas or English. Many of the cattle so captured they must have known to be the property of white men.[xiii] Some branded cattle were found in their possession on the day when the patrol went out from Fort Victoria, others were returned by the more reasonable Indunas, after pressure by Captain Lendy previous to the arrival of Dr Jameson at Victoria. Many of the cattle captured and carried off were the property of the Company or of private individuals;[xiv] and it was pointed out, with some force, by more than one witness, that among natives the capture and carrying off of cattle is an act of war, and it is in fact one of the principal methods of carrying on warfare among native tribes. The Matabele, therefore, who captured white men’s cattle, and retained possession of them, must have known they were liable for the consequences.[xv]

Farming and mining activities at Victoria are severely disrupted

The details set forth in the evidence of the events between the 9th and the I8th July [1893] can hardly be disputed. I take it as proved and accepted that the Matabele were in possession of the whole country side, that they entered the precincts of the town of Fort Victoria, not merely according to map as alleged by Mr. Willoughby, but close to the hospital and church, as deposed by the Civil Commissioner, Mr. Vigers, and others;[xvi] that they squatted on the “commonage” (which I may here inform Rev Willoughby is a tract of grazing ground set apart and adjoining every South African township, for the common use of its inhabitants) and that mining, agricultural, and pastoral pursuits were at a standstill owing to their presence.

The amaNdebele vow to kill all the Mashona refugees within the town

The Induna Manyao entered the town prior to the arrival of Dr Jameson and called upon Captain Lendy, who was magistrate, to hand over to him the Mashona refugees—men, women, and children—whom he saw had obtained a sanctuary in the fort.[xvii] Captain Lendy gave the only reply which it was possible for an officer in his position to give, but he couched it in terms of extreme fairness. He did not exonerate the Mashonas from any charges made against them, but in reply to the grim undertaking by Manyao that he would not kill the prisoners in the river and dirty the water but would take them into the bush and kill them there, he said that as magistrate he would not surrender them untried, but if Manyao would make a charge against them he would try them.

The Administrator, Dr Jameson arrives at Victoria on 17 July

Dr Jameson arrived at Victoria on Monday the 17th July, passing troops of raiding Matabele close to the town. Immediately on his arrival he sent word to Manyao that he must come in on the following day to speak with him.

The indaba at Victoria on 18 July 1893

The Indunas, armed, and accompanied by armed men, duly arrived within 300 yards of the fort.[xviii] Here Sergeant Fitzgerald with four men was sent out to tell them they must lay down their arms, with which order they complied. An indaba was then held about mid-day at the gates of the fort, of which a full account can be gathered from the evidence of various witnesses who were present. Captain Napier acted as interpreter and Mr. Brabant, who also understands isiNdebele, was also in attendance. Besides Dr Jameson, Captain Napier, and Mr Brabant there were present Mr. Vigers, Lord Henry Paulet, Mr Drew, and others.[xix]

Jameson asks Manyao if they are following Lobengula’s orders?

It would appear that Dr Jameson look a strong line in speaking to Manyao and told him he was lying to him and asked him why he had permitted all these proceedings in the neighbourhood. Were they, by the King’s orders, interfering with whites? Why had they killed servants and carried off cattle?

Manyao is given an ultimatum to leave and cross the border[xx]

He then proceeded to ask Manyao whether it was true that he had lost control over his young men, and on Manyao admitting this Dr Jameson told him, “ You, Manyao, and those who obey the King’s orders, must go across the border. I give you an hour to go.”[xxi] (In interpreting ‘one hour’ Mr Napier pointed to the sun as it was then and as it would be in about an hour) “Leave your young men, and I will deal with them.” In saying this, or words to this effect, Dr Jameson pointed at the guns in the fort, thereby giving the Induna to understand that force would be used should the young men decline to retire. He then walked away. The Induna sent a message after him by Lord Henry Paulet to ask where the border was to which Dr Jameson replied: “Tell him he knows.” The meeting then broke up.

Umgandan disrupts the meeting and ignores Jameson’s warning

All witnesses agree in their description of the conduct, of the young Induna Umgandan at this meeting; he was insolent in voice and manner, constantly interrupting the speakers and endeavouring to assert himself. At the end of the indaba he made use of some such expression as: “We will be driven across” or “let us drive them.” The evidence is slightly conflicting as to what he did actually say, but he certainly said something which created the impression in the minds of those present that he meant to disregard the Doctor’s warning.[xxii] The evidence of Dr Jameson and Messrs Napier and Brabant leaves little room for doubt as to this.

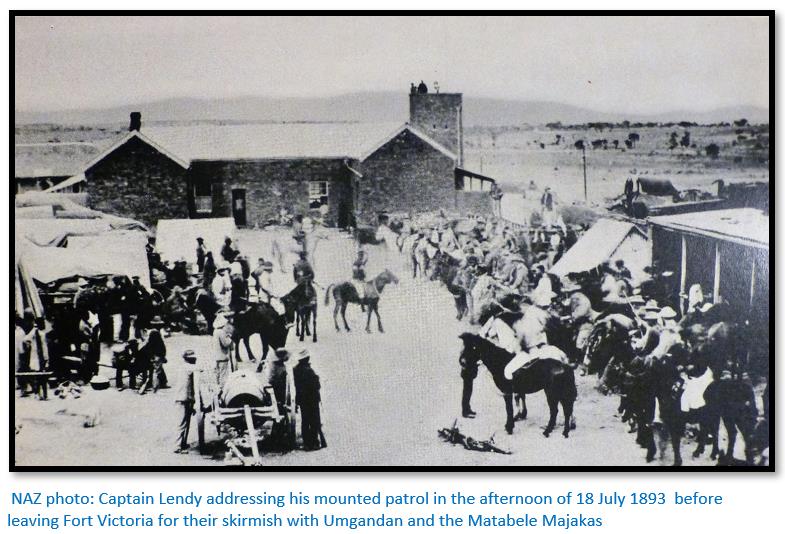

Lendy was given orders to drive away the amaNdebele if they have not left

On the departure of the Matabele, the Europeans went to lunch, and orders were given to Lord Henry Paulet (the officer commanding the Victoria Rangers) by Captain Lendy to select

as many men as he could find horses for, to parade at 2pm for mounted patrol.[xxiii] The parade fell in at 2pm and it was some time after this before Captain Lendy took command.

After the men had fallen in, Dr Jameson deposes that he gave Captain Lendy verbal instructions to the following effect.[xxiv] “You have heard what I told the Matabele; I want you to carry this out. I don’t want them to think it is merely a threat; they have had a week of threats already, with very bad results. Ride out in the direction they have gone, towards Magomoli’s kraal. If you find they are not moving off, drive them, as you heard me telling Manyao I would, and if they resist and attack you, shoot them.” Dr Jameson cannot guarantee that these words were his orders verbatim, but he states that they are probably very nearly so, as the orders were given verbally in the same way as he then repeated them before me.

Lendy’s patrol leaves Victoria

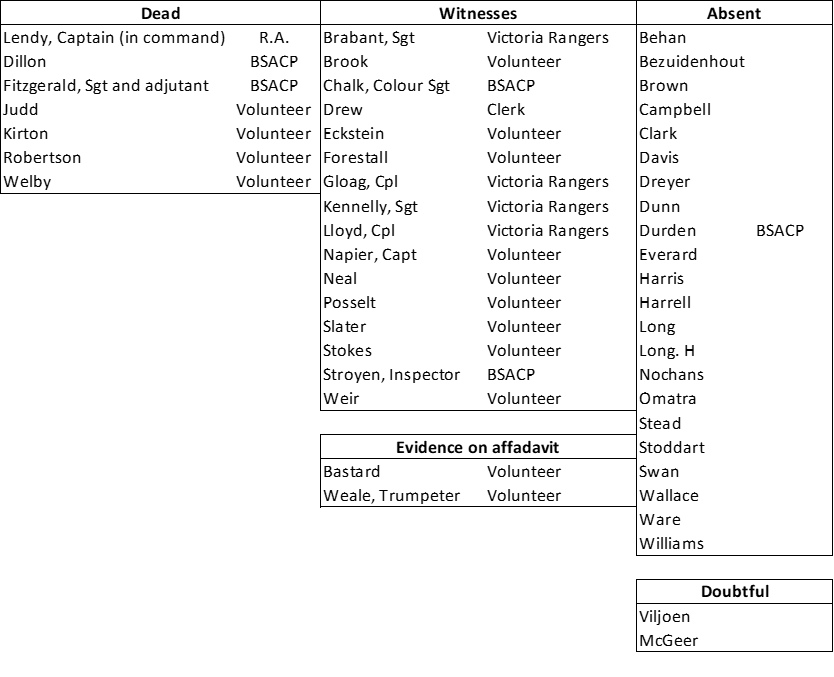

It was about an hour and three-quarters after the close of the indaba when the patrol left the fort in column of half-sections. It consisted of about 40 men. I could get no accurate list of those who formed it, but 35 men were warned, and it is probable that 38 men fell in at the fort, and perhaps some five or six who had horses to ride afterwards joined. A list of the names and ranks of those known to have been present is attached.[xxv] The volunteers rode first out of the fort, the police being in the rear.

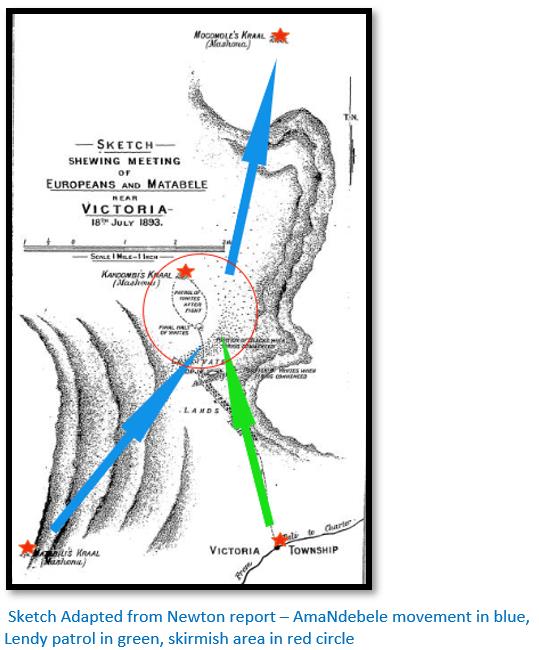

The patrol moves in a north west direction

The columns cantered a few yards away from the fort, and then settled down to a walk (which pace they maintained until the Matabele were sighted), and proceeded in a direction slightly west of north, according to the accompanying sketch.[xxvi] After proceeding a short distance from the town an advance guard of a sergeant and four men was sent forward, and flanking parties thrown out on either side. Sergeant Kennelly, of the Victoria Rangers, was in charge of the advance guard, which consisted of himself and Troopers Bezuidenhout, Brook, Campbell, and Gloag.[xxvii] The course taken by the advance guard and column is shown, I believe, fairly accurately on the sketch, which is drawn from information given me on the ground by Messrs Brabant and Brook.

An amaNdebele raiding party is met after having robbed Mazibili’s kraal

About three and a half miles from Victoria, while the column, which had been at a walk the whole time, was making its way across some fallow ground, the Matabele were first seen, moving slowly, in disjointed lots and groups, from the south west to the north-east, in the direction of Magomoli’s kraal, where it was known that Manyao had his head-quarters. It appears from the evidence that at the end of the indaba, Manyao and the chief Indunas went straight off to their camp near Magomoli’s kraal,[xxviii] which they were investing; that Manyao and the older section of the impi had a strong difference of opinion with Umgandan and the young- warriors, who deliberately announced their intention of staying to continue their raid.

It is also clear that on that same afternoon Makoombi’s[xxix] and Mazibili’s kraals were respectively attacked and raided ; the latter was empty, the inhabitants having fled, but there is every reason to believe that the party of Matabele and Maholi, overtaken by the patrol, was not a regular rear-guard of Manyao’s impi retreating in accordance with Dr Jameson's orders, but simply a lot of Matabele and Maholi, with stolen cattle and grain in their possession, hurrying back from a raid at Mazibili’s to join the main body, when they saw the body of white men mounted and armed. The direction they were taking and from which they were coming, and the fact that some were carrying grain and driving stolen cattle leads me to this assumption;[xxx] and I may here mention that in the course of the pursuit which followed, several men of the patrol observed cattle which had evidently been in the possession of the attacked and flying Matabele. The cattle were not recovered at the time, hut were identified by colour and brand as the property of a resident in the district.[xxxi]

The amaNdebele raiding party is fired upon by the patrol

The Matabele were probably first seen by the advance guard, but small lots of two or three were soon visible to the whole column. As to how the firing actually began, there is some conflict of evidence, which is dealt with later on. It is enough for the present to say that some single shots were fired by the advance guard on receipt of orders from the commanding officer. The general order to commence firing having then been given by Captain Lendy, the column advanced and extended at a canter.[xxxii] The skirmishing order taken at once became a mere chase.

The Matabele beat a retreat, their point evidently being Magomoli’s kraal, where the Induna Manyao and the head-quarters of the Matabele impi were known to be. Beyond the incident of the man who fired at Fitzgerald, referred to later on, a statement by one witness that the Matabele threw an assegai or two,[xxxiii] and by another that a Matabele shook his spear at him,[xxxiv] there is nothing to show that any organised or individual resistance was offered.[xxxv] As a witness said: “They got on the run, and we “kept them on the run.” Those with good horses got to the front and the badly mounted fell behind. The ground was, however, very bad for horsemen, being in places unrideable at any pace, from the deep ridges and furrows of the cultivated land. This fact, and the kopjes close by on the right, saved the lives of many Matabele. After the pursuit, for it can hardly be called anything else had been going on for about ten minutes, Captain Lendy gave orders to cease firing.

The patrol pursue the retreating amaNdebele to Makoombi’s kraal

Some of the patrol had pursued a much greater distance than others; some went on so far as Makoombi’s kraal, which they found being invested by Matabele.[xxxvi] A message was sent back to Captain Lendy to that effect and a few shots were fired at long range at the besiegers, who immediately retired, leaving the fortunate Makoombi and his people free to descend from their kopje. It was from Makoombi that I ascertained that Mazibili’s kraal had been raided on that afternoon.[xxxvii] He had been watching the proceeding and the attack of the whites from his hill-top. On the arrival of Captain Lendy and the main party at Makoombi’s, the patrol halted for a few minutes, and then rode straight back to Fort Victoria which they reached about sundown.

John Meikle’s account

“The mounted men, about sixty in all were ready inside the Fort. We were told to go and have something to eat and, when the two hours had elapsed, we sallied forth, Captain Lendy, an Imperial Officer, in command.

As we rode out of the gate of the Fort, the Matabele were visible, a black shadow as if the sun had clouded over that part of the country. They had been brought on to the low granite Ridge two miles to the west while the indunas came into the conference. Evidently they did not take Dr Jim seriously and were undecided what to do next. As we drew near, they moved off and disappeared over the side. Advance guards were put out and as we passed through a gap in the ridge, it was reported they had coming into touch with Matabele who were retiring. As they arrived in the flat country beyond the ridge, they had spread out and taken to their heels. The country hereabouts was fairly open, with single trees and small clumps of bush scattered about. The order was given to open out in skirmishing order and charge, Captain Lendy drawing his sword and leading. As we came within range, the bugle sounded the open fire. We all dismounted and began firing at the fleeing Matabele. One of the first to fall was the King's nephew, the head induna, who was in command of the expedition. He was a fine, big specimen of a Zulu who was too proud to run and he followed the others at a walk until he fell. He was on my right front, about 150 yards away. Somehow I could not bring myself to open fire on him, although he was nearest to me. Instead I aimed at those who were running. We mounted our horses and charged right into them and it was each man for himself developing into a running fight, if it could be called a fight. It seemed to me to be all one-sided, for no attempt was made by the Matabele to retaliate. This continued for several. miles until no Matabele were in sight. The bugle sounded and we came together. No one was wounded…"

AmaNdebele casualties

The number killed during the brief period of the pursuit has been variously estimated.[xxxviii] The Induna Manyao and his colleague Umyengwane say—and they should know best— that 11 men were missing, of whom nine are believed to have been killed and two to have run away. Makoombi states that of the whole number killed only three were Matabele, the rest were “dogs” (Maholi)[xxxix] The Induna Umgandan, who had so distinguished himself by his insolent behaviour at the indaba, was one of the first shot.

The witnesses

Sixteen of the mounted men in the patrol provided personal witness statements to Newton; two provided sworn affidavits. They are listed as witnesses in the table below.

End of Newton’s narrative

The conclusions drawn by F.J. Newton at the end of his enquiry – this concludes that the allegations made by Rev William Willoughby are unsupported by the witnesses

In conclusion, I have the honour to submit to your Excellency the following conclusions at which I have arrived on the principal points calling for inquiry:

1. That the Matabele did raid European farms as well as Mashona kraals and carried off the cattle of white men.

2. That the Matabele committed wholesale horrors in the Victoria district. This is not disputed.

3. That at the indaba Dr Jameson gave them a fair ultimatum and that there are no grounds for saying that he called upon them to perform the impossible.

4. That the instructions Dr Jameson gave to Captain Lendy were not only justifiable but politic.

5. That Dr Jameson was misinformed when he reported officially that the Matabele fired first on the whites.

6. That the sergeant of the advance guard fired the first shot.

7. That the Matabele practically offered no resistance.

8. That in the pursuit of the Matabele there was no wholesale slaughter of natives nor deliberate shooting of men already shot.

9. That the Matabele, when attacked, had only gone three miles in three hours and were then caught in possession of cattle stolen from Europeans.

10. That the story of the sick Induna being shot, without being absolutely and entirely untrue, is at least, an embellishment of an immaterial fact.

11. That the story of the Matabele warriors asking for, and being refused quarter, is unsupported and highly improbable.

Some specimen Witness reports

Witness statement of Induna Manyao before F. J. Newton at Bulawayo on the 22 May I894

The sun was still early in the day, and the doctor then told us that should we still be anywhere near when the sun was there (pointing to about 4 o’clock) he would talk to them in a different manner. The doctor said nothing about any rivers or border. After the doctor warned us at the indaba, some of our people went and killed some of the white men’s servants. That is why the doctor’s people shot at us. I could do nothing with the young men. I had with me the following:

And we picked up a lot of stragglers—all the Maholi belonging to these towns. In numbers about 2,000 warriors left Bulawayo and I picked up about 1,000 Maholi. Manyao stated that he remembered the doctor at Victoria and also Mr Vigers. Manyao is very sick, having lately had small-pox, with fever on him now. He recognised Mr Newton as the Queen’s representative and was willing to tell all he knew about the occurrences in Victoria last year. He was the head of the Matabele impi sent to the Victoria district and was in command of the party who had an indaba with Dr Jameson at Victoria. Umgandan was also there, second in command. He had brought one letter from the King, but the last one was brought by Umgandan. He gave his letter to Mr Vigers and remembered well what took place on the occasion. Dr Jameson had told them that their men (Matabele) had killed Mashona servants, and it would not be allowed. Dr Jameson refused to give up the native women and children who had taken refuge in the fort, and ordered back the impi over the border, stating that he (Dr Jameson) was in communication with the King direct.

He (Manyao) replied that he could not make his young people re-cross the border and remembered that Dr Jameson then told him and the older men who understood the thing to go back, leaving Dr Jameson to settle with the young men. When Dr Jameson had finished he said, “Now go, or I will drive you across” and he (Manyao) got up and left.

Then Umgandan said, “Very well, we will be driven across.” Dr Jameson told them distinctly that they had exceeded their orders by crossing the Shashe River and that he was in communication with the King. When Manyao went back towards Magomoli’s kraal the young Majakas went and looted a lot of trained cattle out of Mr Vigers’s kraal, including those belonging to the Company and to private individuals. Those cattle had never been returned. Some had also been captured before. Manyao tried to get the cattle given up, but the young men declined and drove them back at the point of their spears.

Umgandan also remained behind to drink water at a spring and while resting under a shady tree got mixed up with the Majakas, with the other Indunas also resting with him. This was when the Majakas were driving the cattle off and were being chased by the horsemen. Manyao then returned straight to the King and told him all that had occurred. They all understood distinctly what Dr Jameson had told to their faces, that he would drive them back beyond the Shashe. But although the matter was discussed between them all, the young men would not do so. Even afterwards on returning the young men raided more cattle and left their Indunas behind.

The Majakas were in possession of the stolen cattle in their own camp when the white horsemen pursued them.

Manyao stated then, Dr Jameson had previous to the same indaba sent a white man and a coloured boy to talk with the impi, and on the way, fortunate for them, that Manyao met them and took them under his protection, as otherwise they would have been killed, as he (Manyao) saw mischief in the eyes of the young men. Manyao took the two messengers away. There was only one sick Induna and he was not carried. That was Umgandan, who was suffering that day from an attack of colic. He was the only one sick. During the indaba Umgandan was very cheeky and constantly interrupted the doctor, who shut him up, saying that he did not want to talk to boys, but only with the men.

Witness statement of Umgengwane, Matabele Induna, sworn by Matabele custom

Was with the body which was pursued by the patrol. We were some distance from the town, as far off as the big tree yonder (about 1 mile) The white men fired the first shot. There was a good many shots. We ran away to where part of our impi was and then cleared. We did not fire back, not the party that was with me, but I do not know if the others did. We were in open order, but pretty thick. I only know of two who were shot. No, I did not see them shot, or their bodies, but I was told so. When we first saw the white men some of us were moving, some sitting down, some drinking water. We were slow in starting; that is why we took so long. We did not start till late. The Majakas went to Makoombi’s kraal after the indaba and overtook us when they were pursued. I was not with Umgandan.

We Indunas had decided to return, but we had a row with the young fellows, who called us cowards and said they were going to stay behind, and they went raiding on their own account. Manyao did his best to stop these young fellows from going out, but he could not. The Majakas went straight to Makoombi’s kraal to raid it. They were there in the kraal raiding when the white men came up with them. That is when the shooting began.

Manyao (recalled) We only know of nine men shot—men killed; there are one or two still missing, but they may have run away.

Witness statement of Lord Henry Paulet (Officer commanding the Victoria Rangers)

Was at Victoria July last; arrived there Saturday, 15th July. Was in command of the Victoria Rangers and had a selection of men for patrol, taking orders from Captain Lendy. I know of two men who lost cattle by raiding of the impi. All work was suspended in the neighbourhood. Everyone was in camp. Several kraals of the Mashonas had been burned to my knowledge within sight of Victoria. Fires wore constantly seen at night. I was present at the indaba on Tuesday, 18th. The doctor took a high hand. Asked the natives why they had interfered with the whites. Manyao said they had not interfered. Doctor said they had taken cattle and killed servants and were not obeying the King’s commands.

Manyao asked the doctor if he would hear what the man who brought the last letter from the King had to say. This man was Umgandan. The letter was to Captain Lendy. Dr Jameson refused to talk with anyone but Manyao. Umgandan was most insolent, constantly interrupting the indaba. The doctor then asked Manyao if he had lost control over his young men. Manyao admitted that he had. The doctor then said, “You, Manyao, and the people who obey the King’s commands, go back over the border. I give you an hour to go. Leave me your young men, and I will deal with them.” Manyao then asked where border was. I took the message to the doctor, who replied: “Tell him he knows.” The Indunas then rose to go. Umgandan made some remark in a loud voice, and Sergeant Brabant said to me, “They mean fighting.’’ I asked him what Umgandan had said, and he translated Umgandan’s speech as being that they would sooner be driven than go back to the King of their own accord.

The indaba took place somewhere between 12 and half past. I then received orders from Captain Lendy to select as many men as I could find good horses for, to parade at 2 o’clock for mounted patrol. The parade fell in at 2, and it was some time after this before Captain Lendy took over the command of the parade. When Dr Jameson gave the order to Manyao I did not conceive that he meant him to cross the border in an hour, because it was an impossibility. We knew they were investing Magomoli’s, a Mashona kraal, about 7 miles distant from Victoria. It was merely to stop this and to make them leave off the burning of the kraals. I understood the doctor’s orders were in consequence of a letter written by Lobengula the year before in reply to a complaint that his people had been raiding the country. I heard nothing about their being given a certain time to clear off the commonage. I am perfectly certain the expression was not used. If it had been used I should have heard it.

(Mr. Willoughby’s Letter, Extract read) - The statement by Mr. Willoughby’s correspondent that Dr Jameson ordered the Indunas across the frontier (30 miles away) within two hours is incorrect. No mention was made of two hours. It was, moreover, at least an hour and 40 minutes before Captain Lendy rode out. It might have been more. It could not have been less. Manyao was mounted and from information from the Mashonas there is no doubt he left straight for the invested kraal and broke up his camp at once. They must have left very speedily as lots of grain and meat were left behind. Manyao and Umgandan were certainly not in accord at the indaba. Umgandan was one of the men killed. He was a young Induna. He was the only one insolent, the others were simply sullen. He was insolent by interruption, gesticulating, and trying to make himself heard. Manyao seemed somewhat afraid of him.

The order was merely given by Captain Lendy for mounted patrol to fall in at 2. Each man had bandolier of 50 rounds as usual, just like every man in the fort. I do not know what Captain Lendy’s instructions or intentions were. I received instructions from him to keep all the men at their posts in the fort until he returned.

I could not say how many kraals there were burned, they were burning all over the place. I only visited two myself. At one there were five bodies, all with their right hands cut off. The labour and mining business was entirely demoralised by the advent of the impi and the raiding. The boys all deserted the mines. The Mashona refugees asked for protection from the white men. Captain Lendy told me before the arrival of the doctor all that had taken place, viz., that the Matabele had asked him to give up the Mashona refugees and that they said they would not kill them in the township, but they must die as they had stolen the King’s cattle. The refugees were men, women, and children. I saw about 15 to 20 from Bern’s kraal. He offered to the Indunas to hold trial as magistrate, as to whether the Mashonas had stolen the King’s cattle. If they (the Matabele) would make a charge against them, and if guilty, he would punish them, but not surrender them without trial. The offer was refused and the Indunas referred to previous cases when prisoners in Buluwayo had been given up to white men. The kraals raided were those from which the native labour of the district was supplied. The Matabele had raided the Victoria district the year previous, destroying grain, etc. A prospector named Jackson had two boys killed on the occasion of this last raid. They also threatened him.

The sending out of the patrol and the acts of that patrol were, in my opinion necessary and justifiable, not only for the protection of the Mashonas, but to restore confidence in the country. In my opinion any less stringent measures would have been regarded by the natives as a sign of weakness and source of danger to the whole community.

I have never heard anything from anyone that the acts of the patrol and the officer commanding it were not justifiable or for the public benefit.

Witness statement of Thomas Arthur Chalk, Sub-Inspector BSA Company’s Police

Was in Victoria last July, was then Second Class Sergeant in the Company’s Police… to Victoria again. On Sunday, the 9th, I heard that natives and cattle were rushing through the town. We (the police) saddled up immediately, rode down the Magomoli road a little past the hospital, where we met a great crowd of them. I stayed there, while some of the other police rode among them on the commonage, close up to the Vicarage. The impi itself was besieging Magomoli’s eight miles off. That week the people there were reduced to great straits for food and water, even to drinking their own urine. For that week an old Mashona Chief, Mazibili, close to Victoria, took refuge in the fort with his people. The country all round was being raided. Natives (Mashonas) assegai’d, were lying on the road within a mile of the township, and several other bodies were found further off. Magomoli’s people were reduced to absolute starvation. Although Manyao, the chief of the Matabele, had a note from Lobengula to Captain Lendy, he did not deliver it until we rode out to Magomoli's and got it.

It was a note to the effect that his impi were going to punish the Mashonas around Victoria and he requested that no notice should be taken of them. A herd boy belonging to a farmer called Eksteen was killed by them. All the white men's cattle were scattered over the country. Some taken by the Matabele, others lost because the herds were either killed or had run away. Manyao, when he first came in, said the white men’s cattle would be given up. The second time, when he came to see Captain Lendy he saw the native women and children who had taken refuge in the fort, and asked Captain Lendy to give them up to him, saying: “I won’t pollute your water, I will take them over the stream,” meaning to kill them. Captain Lendy said, “No, show me any that have done any harm or wrong, and I will try them, and if guilty will hand them over.” Manyao insisted on having them, saying he must have them all. Captain Lendy would not give them up. Manyao then went away in a rage. Said he would not give over the cattle. We all went into the fort then.

The place had been in a state of siege for some time when the Administrator came down. I was sent out with an escort to find some Matabele to tell them that the great White Chief had come down and that their Induna must come in and have an indaba. They said something to me which Mr. Brabant translated as, “When are we to be allowed to fight the white men?” I replied that I did not know. The place was in an absolute state of siege, nothing but night and day patrols. The outside stores all had to come in, bringing their stuff with them. I was one of the escort who went out to bring the natives in to the indaba. They were coming in a large body, and four of us, under Fitzgerald, met them 300 yards from the entrance to the fort, and told the Induna and those of his people who were coming in that they must leave their arms. They laid down their arms and went up. I was present and standing within 12 yards. I did not hear all that was said, as I am deaf. I heard towards the finish the doctor tell Manyao that he had lied several times. I heard the doctor ask Manyao if it was a fact that he had said that he was unable to control his young men, and Manyao replied, “Yes, it was so.” The doctor then said, “Well, you and your old men go away quietly, and leave me to deal with your young men.” The doctor said he would give them either one or two hours to clear out. The interpreter defined the time by pointing at the sun.

Umgandan, a minor chief—a young man, had been interrupting during the greater part of the indaba; and he went away very cheekily. He was offensive in his manner. We waited from two hours to two hours and a half. Some were saddled up and some got the order at the end of that time. I was in charge of the police; there were four or five of them. We left about 2.30 or 3 and rode along for about an hour. I was in the rear. We took the right of the line and Captain Lendy went out left in front. The force was composed of Victoria Rangers, burghers and police.

I heard firing in front of the line. We went in column of half-sections, when the firing began, and as we got up they extended. The bugle sounded, “commence firing.” There was one shot fired before the trumpet sounded. I could not say from which direction the shot came. I am perfectly sure I heard a shot fired before the trumpet went. I could not say from which direction the shot came. I cannot locate sound, as I am deaf in one ear. The shot was certainly fired before I heard the trumpet. He might have sounded “commence firing” more than once. I do not know who was trumpeter. My impression is it was Weale. He is probably in Victoria now. Mr Vigers should know. We were then in an extended line. We were slightly in rear, on the right. I was riding close to Captain Lendy when I myself first saw the Matabele. They were running away, and we were pursuing them. We got within 200 or 300 yards. That was the closest I saw at any time. We were cantering, dismounting, shooting, and so forth.

I did not see any natives actually drop to a shot, but I saw them on the ground, dead. I saw about four or five. It is impossible to estimate how many there were killed. I do not think there were as many as 30. I saw nothing of a sick Induna being carried. I never heard of it, until you mentioned it now. I never saw or heard anything of natives asking for quarter and being refused. From my knowledge of the Matabele, I should say, they are not in the habit of asking for quarter. This would not apply to the Maholi (serfs) Personally I saw no show of resistance. Sergeant Fitzgerald, however, told me a man jumped up out of the grass, and shot at him. He shot him dead. I have no means of saying what the Matabele were doing when we overtook them, as I was quite in the rear. There were some cattle about. I first saw them just before the ‘‘cease firing” sounded. I believe they were driven in. I do not know whom they belonged to. It appeared to me that the cattle were driven away by the natives we attacked. The appearance of those who ran away, and those who were shot, was that of young men—Majakas. A Majaka is a young unmarried warrior, a generic name for soldier. I have no means of saying, who fired the first shot. All I know is, I heard a shot fired before I heard the “ commence firing ” sounded.

Conclusions on some of the more contentious issues

Lendy apparently told Jameson: that the first shot was from the Matabele.

Newton says: “The question as to who fired the first shot thus arises; and it is necessary to examine the evidence, which is very conflicting, before stating any conclusion on the point.”

Lendy was supported by the men with him - Napier, Brabant, Fitzgerald and Weale, the bugler. But they were all with the main body of the patrol and not with the advance guard. Clearly the beginning of the incident itself was the subject of “some conflict of evidence” and perhaps that is why Newton made no allegation of Lendy having lied or being mistaken – the evidence against Lendy was not overwhelming or incontrovertible.

Sergeant William Kennelly in charge of the advance guard with four men, Bezuidenhout, Brook, Campbell, and Gloag said in his witness statement: “They were about half a mile off when first I saw them, about 60 or 70. We could see them quite distinctly, with their shields prominent. I saw no man being carried. I got to within 200 or 300 yards, and then sent Gloag back with a message (verbal) to Captain Lendy reporting the Matabele, their number, and the direction they were taking. Gloag brought a message back from Captain Lendy to say I was to open fire, and I also heard the bugle sounding the “commence fire.” I fired a shot in the air. That was the first shot I heard and I fired it after receiving orders from Captain Lendy. I closed in my advance guard and by that time the main body had closed up and the firing became general.”

Trooper Brook, also in the advance guard, stated that by the time the order, through Gloag, had been received, the Matabele had rounded a small kopje in front, so: “we had to go some distance to sight them again- This was after the order was received to commence firing, but before the first shot was fired - Kennelly fired the first shot.”

Newton concluded that the evidence of the witness statements seemed to show: “...that the first shots seen and heard by them and everyone were the shots fired by the advance guard [of Lendy's patrol] The weight of evidence appears to me to favour this view.”

There were allegations of slaughter and shooting of wounded amaNdebele warriors

The statement in a newspaper: “It was like buck-shooting, for the poor devils took to their heels and we galloped up and almost shot them point blank. I don’t suppose any of them got less than four or five bullets in him.” Newton concludes this is highly coloured. One or two men were shot at close range, but the evidence is incontestable that most of the firing was at a range of over 100 yards. Newton says the expression: “It was like buck-shooting” seems intended to convey the idea of horsemen riding, as it were, into a troop of springbuck. Nothing of the kind occurred, and every witness examined on the point[xl] has denounced the statement as misleading or untruthful. The supposition that none of the killed got less than four or five bullets in him is probably exaggerated from the fact that the Induna Umgandan who was conspicuous from the ostrich feathers he wore, was fired at and hit by two, if not three, men.

Newton concludes that in the pursuit of the Matabele there was no wholesale slaughter of natives, nor deliberate shooting of men already shot.”

Truth magazine quoted the following: “Last Tuesday the Matabele came into camp . . . Dr Jameson held an indaba and gave them one hour to get out of Mashonaland

Additionally the Times carried a statement: “The end of it was, Jameson told him (the head Induna, Manyao) he gave him (Manyao) an hour to give up the cattle and get over the border, and if they were not across by then, we should help them.” The Rev W. Willoughby made the same allegation but states the amaNdebele were given two hours.

The allegation is that the Matabele were to retire across the Shashe river, 30 miles away, within one hour…an impossible task.

Newton concludes that the witnesses are almost unanimous[xli] that Dr Jameson “ordered the Matabele to clear, or be on the move, or to start, or words to that effect, within one hour, and that the space of an hour was indicated by Mr. Napier, the interpreter, by the position of the sun.” Rev Willoughby himself quotes the correct story in his letter to the Victoria newspaper, which says that Jameson: “simply tells them to clear within an hour, or he will make them.”

Sir Henry Loch added: “…The evidence shows beyond all doubt that Doctor Jameson’s order was for the Matabele to withdraw within one hour—not across, but towards, the border; that it was a wise and proper order to give and was fully understood by the Matabele. The young men having only gone some three miles in three hours and having stolen cattle belonging to the white residents (in itself an act of war) was ample justification for the action taken by Captain Lendy to enforce obedience to an order deliberately given, and upon the enforcement of which, as it would appeal to native intelligence, depended in a great measure on a stop being put to the raiding on the Mashonas, and, to the Europeans, exemption from the danger of being attacked in their laager at Victoria.”

List of the names and ranks of those in Captain Lendy’s patrol

References

Alan Doyle. The lower Sunbury Lendy Memorial

Report by Mr F.J. Newton upon the circumstances connected with the collision between the Matabele and the forces of the British South Africa Company at Fort Victoria in July 1893

Stafford Glass. The Matabele War, Longmans Green and Co, 1968

N. Jones. Rhodesian Genesis. Bulawayo 1953

Notes

[i] The Matabele War, P68

[ii] James Dawson (1851 – 1921) traded at Bulawayo in partnership with James Fairburn. He had a legal background and was well-liked by the amaNdebele who called him ‘Jim solo’ and was trusted by Lobengula.

[iii] The Matabele War, P70

[iv] Johann Willem Colenbrander (1855 – 1918) Traded in Bulawayo from 1888 and the following year became the representative of the BSA Company. In 1894-5 was a native commissioner in Matabeleland and saw service in 1896 and the Anglo-Boer War. Drowned during filming whilst playing the role of Lord Chelmsford.

[v] F.J. Newton was then the colonial secretary of Bechuanaland

[vi] The figure of 300 amaNdebele was Lendy’s and appears to be an exaggeration of the actual number

[vii] As stated by Lendy and is disputed

[viii] Caldicott the civil commissioner stated the white population of Victoria at that time of the incident was about 400 men and probably 90 women and children. The total number of the impi, from native sources was from 5,000 to 7,000 men.

[ix] Witness statement: Manyao

[x] Maholi or slave people (i.e. young men sized in amaNdebele raids into Mashonaland)

[xi] Witness statements: Paulet, Vigers, Napier, Weir, Chalk, Forrestal, Brabant, Makoombi

[xii] Witness statement: Makoombi

[xiii] Witness statements: Napier, Neal, Brooke, Brabant, Eckstein

[xiv] Witness statements: Napier, Weal, Neale, Manyao, Gloag, Slater, Forrestal, Brook, Brabant, Bastard

[xv] Witness statements: Neal, Moffat, Colenbrander

[xvi] Witness statements: Vigers, Weir, Chalk, Brabant, Brew, Willoughby

[xvii] Witness statements: Paulet, Vigers, Napier, Chalk

[xviii] Witness statements: Chalk, Forrestal, Eckstein, Drew

[xix] Witness statements: Paulet, Vigers, Napier, Jameson, Manyao, Chalk, Forrestal, Brabant, Drew, Bastard

[xx] A map of the border is included in the article Re-examining the events leading up to the ‘Victoria incident’

[xxi] Witness statements: Paulet, Vigers, Napier, Jameson, Chalk, Brook, Brabant, Eckstein, Stroyen, Drew, Willoughby, Bastard

[xxii] Witness statements: Paulet, Napier, Jameson, Manyao, Brabant

[xxiii] Witness statement: Paulet

[xxiv] Witness statement: Jameson

[xxv] See the List of the names and ranks of those in Captain Lendy’s patrol

[xxvi] See the Sketch Adapted from Newton report

[xxvii] Witness statements: Kennelly, Gloag, Brook

[xxviii] Witness statement: Manyao

[xxix] Witness statement: Makoombi

[xxx] Witness statement: Brabant

[xxxi] Witness statements: Napier, Weir, Posselt, Neal, Manyao, Slater, Gloag, Bastard

[xxxii] Witness statement: Stokes

[xxxiii] Witness statement: Slater

[xxxiv] Witness statement: Stokes

[xxxv] Witness statements: Kennelly, Posselt, Slater, Forrestal, Brook, Weir

[xxxvi] Witness statements: Forrestal, Brabant, Makoombi

[xxxvii] Witness statement: Makoombi

[xxxviii] Witness statements: Jameson, Posselt, Brook

[xxxix] Witness statement: Makoombi

[xl] Witness statements: Napier, Weir, Stokes, Kennelly, Posselt, Forrestal, Brabant

[xli] Witness statements: Jameson, Manyao, Stokes, Napier, Weir, Kennelly, Neal, Gloag, Chalk, Brook, Bastard