World Wildlife Crime Report – Rhino Horn

Introduction

This article almost entirely relies on the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report called the World Wildlife Crime Report 2020: Trafficking in Protected Species hereafter called “the report.” I have extracted most of the information relating to rhino horn from that report which is available as a pdf from the website.

The report draws its information from the seizure data in UNODC’s World WISE

Database which now contains just under 180,000 seizures from 149 countries and territories. This is supplemented by the new CITES illegal trade reporting requirement. CITES parties are required to submit data on all seizures of wildlife made in the previous year and this data for seizures that took place in 2016, 2017 and some countries for 2018 is included in the database.

Readers should note that all rhino horn markets are entirely illegal. Rhino horns are products without a legal international market – zero trade is permitted for commercial purposes and there is no domestic market in range states.

In the last World Wildlife Crime Report, elephant ivory and rhino horns were discussed separately. Ivory was discussed under the heading of “art, décor, and jewellery” and as an

investment commodity. Rhino horn was classified as a traditional medicine, although it was already apparent at that time that it had also become a status item. In the last four years,

the evidence has mounted that rhino horn is also being sold for its artistic and investment value, so it is similar to ivory in this respect. The two commodities are sourced from different regions in Africa but require similar skills and equipment to procure. They also share many commonalities in their primary destination markets.

The poaching of both elephants and rhinos appears to be in decline. For elephant ivory, a downward trend since 2011 can be seen in the best available indicators of poaching, smuggling, and price. A similar, but more recent, trend can be seen with rhino horn poaching and prices, although seizures of rhino horns have continuously risen. A 2019 surge in very large seizures of both commodities may be related to the unloading of stocks in response to declining prices.

How the value of seizures of rhino horn has doubled in value

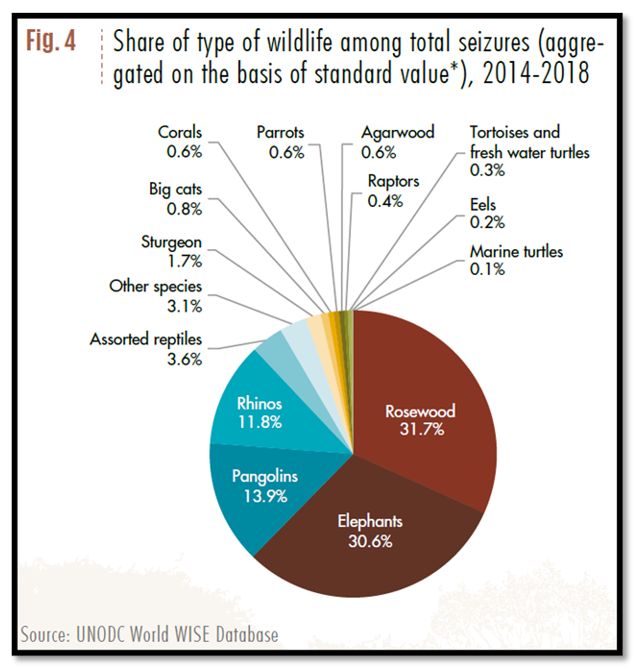

The 2009-13 period figures showed that, on the basis of the value of seized shipments, rhino horn accounted for 5.5% of the total value: only marginally ahead of pangolin (4%) and the value of assorted reptiles (4.3%) but a long way behind elephants (33.1%) and rosewood timber (40.7%)

But for the period 2014 – 2018 the above chart shows the value of seizures of rhino horn has increased to 11.8%; pangolins also increase to 13.9% with corresponding decreases in elephant ivory (30.6%) elephant ivory (30.6%) and rosewood timber (31.7%)

Routes used for trafficking rhino horn from Africa to Asia

Rhinoceros facts

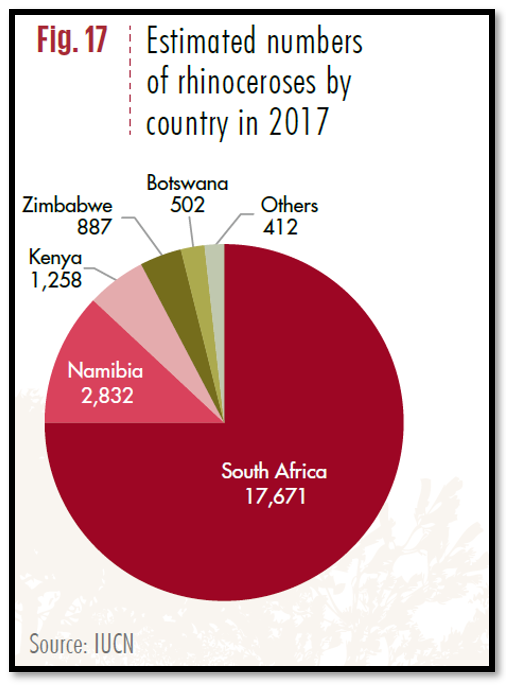

African rhinos differ from African elephants in that there are far fewer of them, and they are far more concentrated geographically. For every remaining African rhino (about 25,000 of them) there are perhaps 20 African elephants, and while it takes five countries to comprise three-quarters of the remaining elephants, 75% of the remaining rhinos can be found in just one: South Africa. (Fig. 17)

South Africa has been so successful in breeding rhinos that it has managed to export 538 live rhinos since 2014, feeding growing wild and captive populations in other countries. Drought and poaching have caused South Africa’s rhino population to decline since 2012, however, driving down the overall continental population. Around 7,500, or over 40% of South African rhinos are privately owned by ranchers and private game reserves. These operations have weathered a decline in the price of a live rhino by two-thirds between 2007 and 2018. While legal prices have declined, the threat of poaching has imposed substantial security costs for rhino ranchers. In this way, the illegal trade poses an additional threat to rhino populations: it threatens to make these private holdings unsustainable.

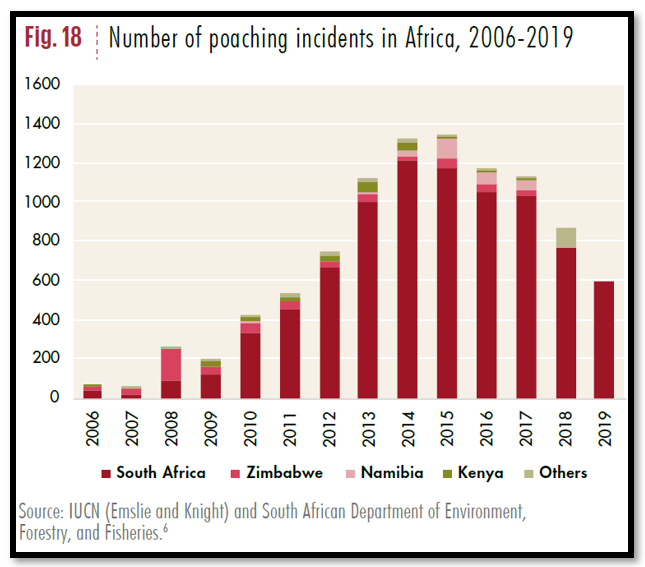

Rhino poaching shows a decline

As with elephant ivory, there have been recent signs of a decline in the market for rhino horn, as both supply (poaching) and price indicators are declining. South Africa, which experienced 86% of the recorded poaching incidents between 2006 - 2017, has seen a declining trend in its poaching numbers every year since 2014. In 2019, the number of poaching incidents decreased to 594, the lowest level since 2011. (Fig. 18)

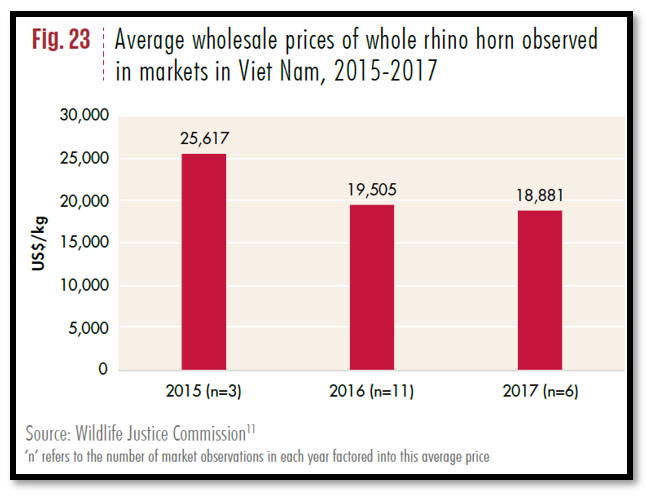

Prices of rhino horn have similarly declined

Prices currently paid for rhino horn in Asian markets are a fraction of those cited

in the popular press. It has been suggested that raw horn was worth US$65,000 or even US$100,000 per kilogram around 2014-2016, while field monitoring suggests the 2019 price was closer to US$16,000. The simultaneous decline in poaching and prices suggests that these illicit markets are contracting. It is possible that stockpiles are being tapped, reducing the need for poaching, but the associated decline in price indicates current supplies exceed demand.

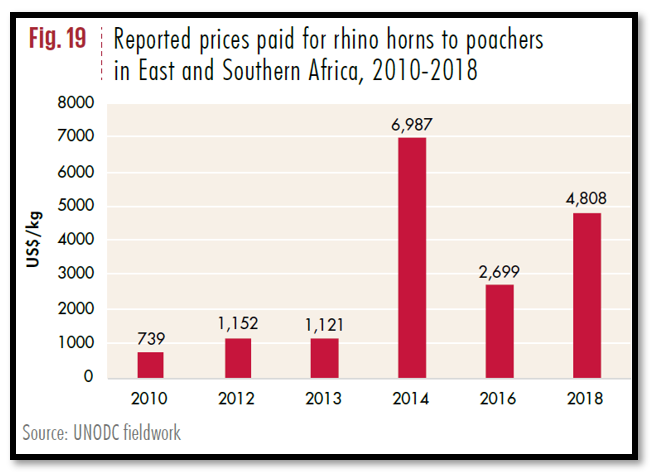

Anecdotal data gathered on prices paid to poachers historically in Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa in 2018 were erratic and showed no clear trend. The consensus was that the price increased dramatically between 2013 and 2014 and had declined since then (Fig. 19) among experts interviewed, however, was that the price increased dramatically between 2013 and 2014 and had declined since then (Fig. 19)

Trafficking in rhino horn

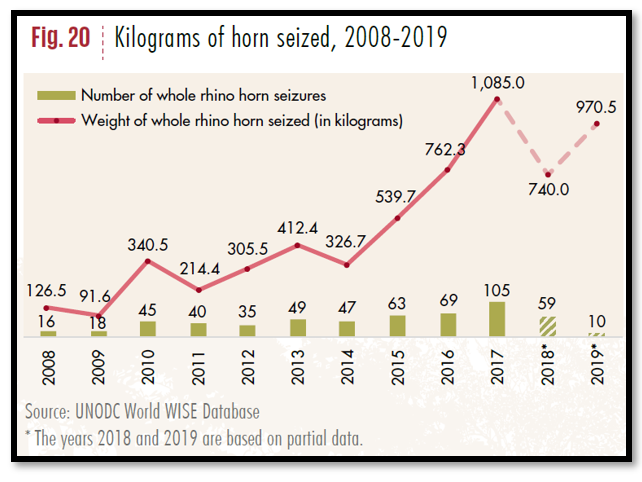

World WISE shows a strongly increasing trend in the number and weight of rhino horns seized, from 16 seizures in 2008 to 105 in 2017 (Fig. 20) This trend stands in contrast to the declining number of poaching incidents and suggests increased enforcement has resulted in a higher share of the illicit flow being captured, or that some of the horn being seized is flowing from either public or private stockpiles.

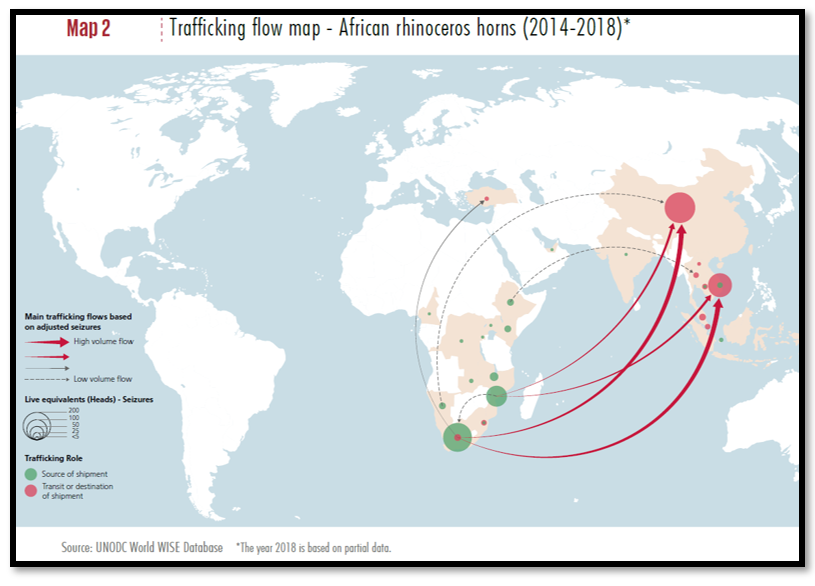

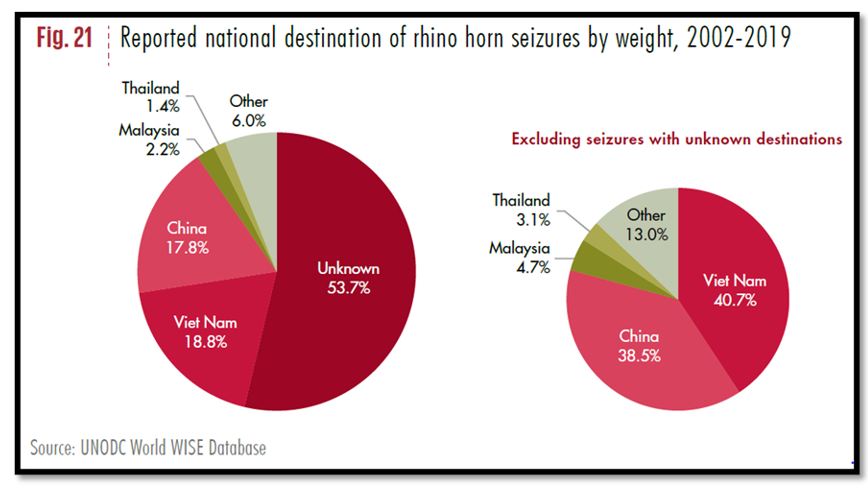

Based on World WISE data between 2014 and 2019 where the final destination was known, accounting for about two tons of horn, more than three-quarters of the weight of horn was destined for China and Viet Nam. (Fig. 21)

Many of the seizures made in South Africa were domestic; the intended destination of this horn was unknown. Because rhino horn is relatively portable and value intensive, the vast majority is trafficked by air in luggage and personal carry-on (sometimes wrapped in tinfoil) and is seized at airports with a relatively large number of seizures involving arrests.

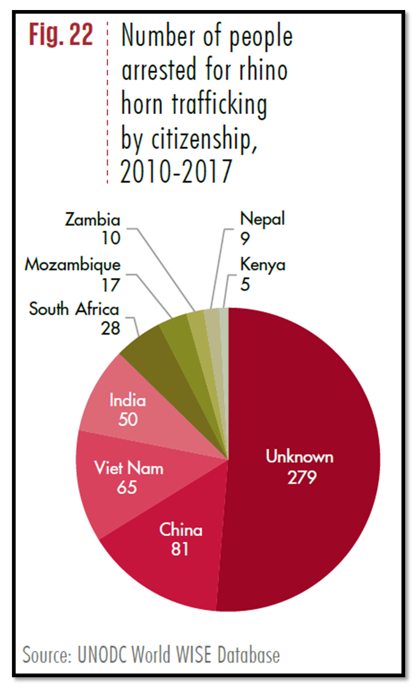

According to World WISE data for the period 2010 to 2017, Chinese (including 24 suspects in 2017 alone), Vietnamese, Indian, and South African nationals are most commonly implicated in rhino horn smuggling. Most of the Chinese suspects were arrested in China or South Africa; most of the Vietnamese in Viet Nam or Mozambique. All the Indians arrested were arrested in India, but it is unclear whether the horn they were carrying was of African or Indian origin. All the South Africans associated with seizures recorded in World WISE were arrested in their home country, although, according to the CITES Secretariat, in April 2019 a South African national was arrested in Vietnam and 13 rhino horns confiscated. (Fig. 22)

Maputo (in the suburb of Matola and at Maputo International Airport), Johannesburg and Hanoi are the three places where the most rhino horn has been seized. More recent seizures found in World WISE include the following:

--- On 20 August 2018, 116 kg of rhino horn enroute to Viet Nam were seized in Malaysia.

--- On 5 January 2019, 116 kg of rhino horn enroute to Dubai were seized in South Africa.

--- On 8 February 2019, 21 rhino horns coming from South Africa and enroute to Vietnam were seized in Istanbul, Turkey.

--- On 14 February 2019, 40 kg of rhino horn coming from South Africa and enroute to Vietnam was seized in Hong Kong, China.

--- On 5 April 2019, 82.5 kg rhino horn from South Africa and enroute to Malaysia were seized in Hong Kong, China.

Since most of these seizures took place in the first quarter of 2019 and amounted to almost 500 kg, the year is on track to be another record year for rhino horn seizures. At the same time, poaching is clearly declining. If the 600 rhinos poached in South Africa in 2019 each had five kilograms of horn, then about three tons would have generated that year, and more than one-sixth of that total would have been seized in just the five seizures detailed above. Just like ivory, the conclusion is that either the rate of interdiction has gone up or that a non-poaching source of rhino horn must be feeding the market, such as stockpiles.

Destination markets

Based on trafficking data, most rhino horn is destined for the consumer markets in China and Vietnam. Recent market surveys have shown that, similar to ivory, demand for rhino horn in Vietnam often involves Chinese nationals seeking to move the product to China. These surveys indicate a growing demand for rhino horn jewellery and décor items, including traditional libation bowls, rather than medicine.

Price of rhino horn in decline

Also similar to elephant ivory, the prices paid for rhino horn appear to be in decline in Vietnam since around 2014 or 2015.

Analysis of the rhino horn market

It is too soon to confirm a decline in the rhino horn market. Like elephant ivory, declines in new supply (poaching) seem to be teamed with declines in price in the destination markets. Unlike elephant ivory though, rhino horn seizures show an upward trend. This could be due to improvements in the rate of interception, or a genuine increase in the flow. If the flow has increased as poaching has decreased, this would suggest the new supply is coming from existing stocks. Many of these stockpiles are in private hands and can be sold in some range states. Sellers may be motivated by declining prices and possibly declining interest.

References

World Wildlife Crime Report Trafficking in protected species 2020. May 2020. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna

South Africa.