World Wildlife Crime Report: Trafficking in protected species 2020 - Overview

Background

This website has highlighted the plight of Chinese farmed wildlife in previous articles. Three-quarters of all emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic transferred from animals to humans,[i] facilitated by environmental destruction and wildlife crime. The UN report[ii] that this article is based upon states that links between the global health crisis and the illegal exploitation of wildlife have been in the spotlight since it was suggested that wet markets[iii] [such as Wuhan] selling wildlife, in this case pangolins, could have facilitated the transfer of COVID-19 to humans. The spike in public awareness of this connection has led to a push for new bans on the sale of wild animals for consumption.[iv]

“If you take wild animals and you put them into a market with domestic animals or other animals, where there's an opportunity for a virus to jump species, you are creating … a superhighway for viruses to go from the wild into people. We can't do this anymore. We can't tolerate this anymore. I want the wild animal markets closed.”

DR. IAN LIPKIN

Infectious Disease Expert

“The animals have been transported over large distances and are crammed together into cages. They are stressed and immunosuppressed and excreting whatever pathogens they have in them. With people in large numbers in the market and in intimate contact with the body fluids of these animals, you have an ideal mixing bowl for [disease] emergence.”

PROF. ANDREW CUNNINGHAM

The Zoological Society of London

3 out of every 4 new or emerging infectious diseases in people come from animals. Report on Zoonotic Diseases, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

Wildlife crime is a global business

The UN report shows wildlife crime to be a business that is global and very profitable with high demand driving high prices; and extremely widespread. Nearly 6,000 different species of fauna and flora have been seized between 1999 and 2018, with nearly every country in the world playing a role in the illicit wildlife trade.

The report refers to the many challenges which Governments worldwide face in preventing and countering wildlife and forest crime. It points out that introducing legal regulations on wildlife crime can trigger replacement effects, for example, geographic displacement of trade exploiting legislative gaps between countries, or a shift from protected to alternative species. Continuous and impartial research and analysis, as well as ensuring legislation is consistent within countries and across regions are essential to eliminate loopholes.

Key to strengthening the global regulatory system is identifying and addressing the vulnerabilities of legal markets to infiltration by the illicit trade is also vital. Public awareness of the scale and impact of the threats posed by wildlife crime can help reduce demand for products of the illegal wildlife trade and increase support for action.

Overview from the World WISE Database[v]

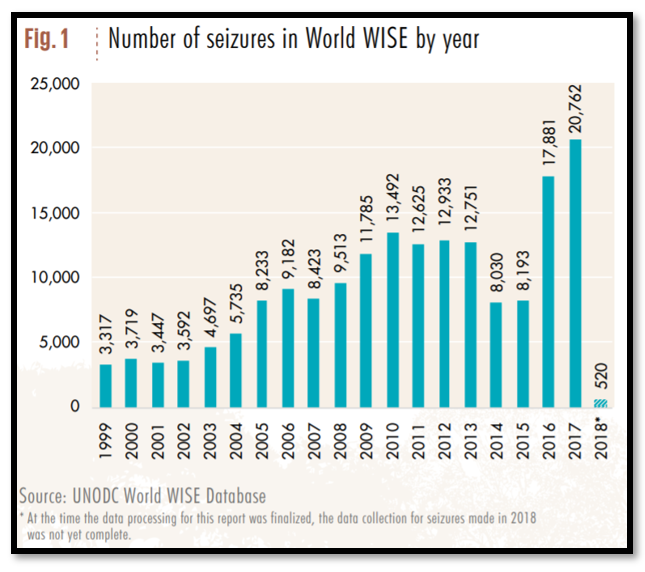

The report draws heavily on the seizure data compiled in United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC) World WISE database that currently has information on just under 180,000 seizures from 149 countries and territories. This is cross-checked with the CITES illegal trade reporting requirement in which CITES Parties are required to submit data on all seizures of wildlife made in the previous year.

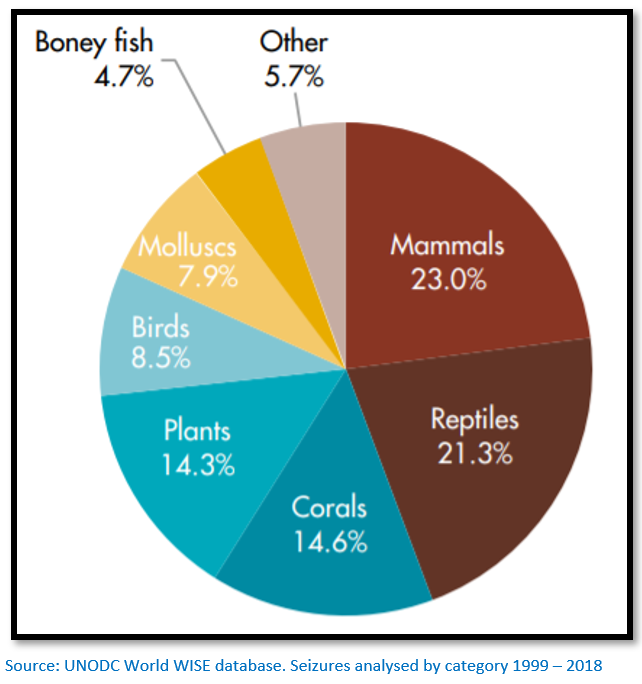

The World WISE Database has data on nearly 6,000 species that have been seized between 1999-2018, including not only mammals but reptiles, corals, birds, and fish. No single species is responsible for more than 5% of the seizure incidents. Virtually every country in the world plays a role, and no single country is identified as the source of more than 9% of the total number of seized shipments captured in the database. Suspected traffickers of some 150 citizenships have been identified, illustrating the fact that wildlife crime is truly a global issue.

The report tells us that the value of seizure data comes not from what they say about the country making the seizure, but what they say about the whole supply chain. Whether transported by sea freight, air freight, personal courier, or post, it is often possible to determine where the contraband originated, transited, and was destined. Each seizure incident, therefore, has the potential to reflect on the entire trafficking chain, including the countries where the contraband went undetected.

Using the value of the seizures as the criteria changes can be seen over time in the total seizures. Between 2009 - 2013, rosewood was dominant, rhino horns and pangolins represented only 5.5% and 4% of the total respectively, and agarwood[vi] also stood at 4%. But between 2014 - 2018, rosewood’s dominance declined as the market shifted to new species and both rhinos and pangolins comprised a much larger share of the total seizures than in the past.

The report draws some conclusions:

With regard to destination markets, considerable media attention is often given to open street markets where a wide range of protected species-products are often openly displayed. Although of course they exist these markets cannot account for the volumes of wildlife illegally harvested each year. Based on the locations of the largest seizures, border town bazaars and back alleyways do not appear to be the venue where tons of fish, timber, and other wildlife products change hands. These volume commodities are usually marketed to specialists out of sight.

Some seizures seem to suggest that some groups are involved in smuggling multiple species. For example ivory and pangolin scales have been found in the same shipment. Information from the World WISE database indicates this is the exception rather than the rule, most shipments are of a single species. It appears that traffickers appear to specialise, trading in particular commodities where they know their buyers well.

Illegal and Legal Markets

Some markets are entirely illegal. For example, rhino horns are products without a legal international market – zero trade is permitted for commercial purposes and there is no domestic market in range states.

Similarly, there is no legal international market for pangolin products since all species were put on CITES Appendix I in 2017, yet growing volumes are seized each year.

Others have legal markets. A large share of the illegally acquired rosewood and European eels are ultimately processed and sold in a legal market. By introducing illegal products into legal markets, traffickers have access to a much broader pool of potential buyers. The buyers may be unaware of the illegal origin of the product. People buying rosewood furniture or eels may have no way to ensure the origin of these products. They suggest supply-chain security is of the essence in protecting vulnerable species.

Criminals exploit countries that are less capable of capturing them

The report states that combating wildlife and forest crime has not usually been seen as a priority when addressing organized crime. Legislation may be weak and the level of detecting and addressing wildlife crime may be very low because of limited law enforcement capacity.

Criminals tend to exploit legislative and enforcement gaps in countries that are less capable of addressing them, with the result that wildlife crime is drawn to these countries. For example, pangolin scale traders may store their stock in the Democratic Republic of the Congo rather than source countries due to a belief there is less chance of being caught.

Criminals will shift from one wildlife species to another

Criminals can shift from protected species to alternative species that have a similar value in destination markets. Examples include rosewood where the source has shifted from Asian to African species. Similarly, after pangolins were overexploited in Asia, traffickers switched to sourcing African pangolins from West Africa. Leopard, jaguar and lion bones have also emerged as substitutes in the tiger bone trade. Often the buyers are not aware that a new species has been introduced.

Much of the illegal wildlife trade is conducted online

The report cites the illicit pet reptile trade that increasingly involves the use of social media platforms. When detected criminals are often quick to switch online platforms and states this trade is particularly difficult to address due to its hidden nature, inconsistent regulatory frameworks and limited specialised law enforcement capacities.

Where no viable wild population exists criminals turn to captive breeding

Captive breeding has been seen as an effective solution for the preservation of species threatened with extinction, but captive breeding can be easily exploited by organized crime

groups. Several countries including China allow captive breeding for commercial purposes with the responsibility to ensure that these businesses operate in line with national regulations. There is evidence that criminals have used some licensed breeding facilities to illegally supply the illegal trade in exotic pets, luxury products and ingredients for

traditional medicine. Pangolin and tiger examples are cited.

Trafficking of elephant ivory and rhino horn

From the end of 2017 all trade in ivory and ivory products in China was made illegal. This sharply restricted the illicit market and prices went into a steep decline.

The report suggests the loss of the legal market may have undermined investor confidence, flooding the market with more ivory than required by retail demand.

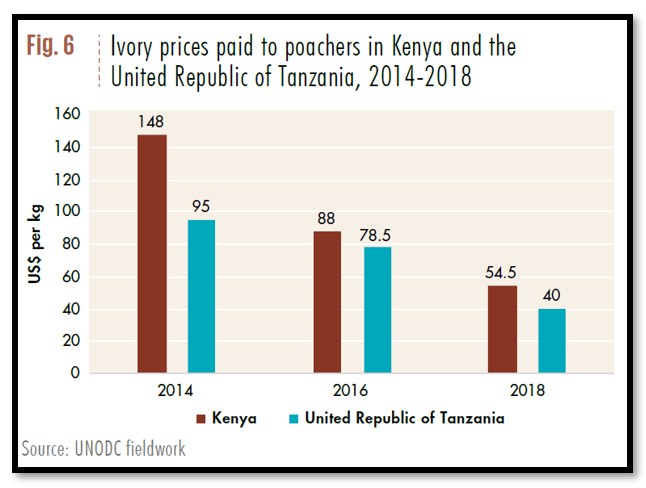

UNODC’s data on poaching and trafficking indicate that the elephant ivory supply grew steadily from 2007 to 2011, declined until 2016 and stabilizing at much lower price levels in 2017 – 18. Similarly prices in both East Africa and Asia appeared to have risen from 2007, peaked around 2014, and to have declined dramatically in the following years.

Similarly, rhino horn poaching also appears to have risen from 2007, peaked in 2015, and declined every year since that time, with prices also declining during this period. Prices currently paid for rhino horn in Asian markets are much lower than reports suggest. Many newspaper reports suggest that raw ivory horn was worth US$65,000 - US$100,000 per kilogram around 2014-2016, while field monitoring suggests the 2019 price was closer to US$16,000.

The illicit markets in elephant ivory and rhino horn may be contracting. It is possible that stockpiles are being tapped, reducing the need for poaching, with boosted supply reducing demand with an associated decline in price.

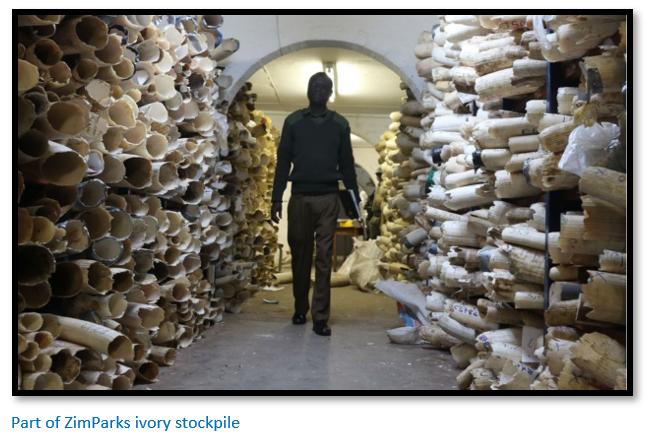

Zimbabwe has major elephant ivory stockpiles

Zimbabwean newspaper articles such as: ‘US$600m ivory stockpile can transform ZimParks’[vii]

with ZimParks saying that the ivory ban stifles conservation efforts. There is some sympathy for ZimParks whose annual income of $24m is dwarfed by its expenditure of $37m (a shortfall of about US$2.5m) but there is serious international mistrust. Firstly, that the legal ivory will provide cover for the sale of illicit ivory and also that the proceeds in Zimbabwe would be used by the political elite / police / military rather than for wildlife conservation. The almost total loss of revenue to the public purse from the Marange diamond fields in the Chiadzwa district provides evidence of this practice.

Seizure data also shows changes in traffic routes. East Africa, particularly Mombasa, Kenya, was the primary source of illicit shipments in the past, but Nigeria has become a dominant collection and transit point over the last four years. Similarly, China was the primary destination in the past, now it is Vietnam. Recently large mixed shipments of elephant ivory and pangolin scales suggest experienced ivory traffickers are using their expertise to move both illicit commodities.

Corruption is a critical enabler of the illicit wildlife trade

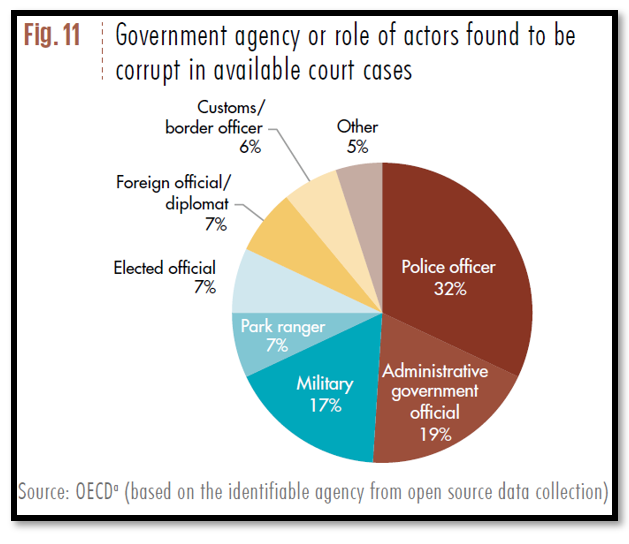

The UNODC reports that a common theme in the illicit trade of ivory and rhino horn (and more generally with all illicit wildlife trade) is corruption in the form of bribes. It takes place at all stages of the supply chain - sourcing, transit and export stages and involves public and private sector abuse of power and trust. It can involve small amounts of money and lower-level officials, or systemic corruption, involving larger amounts of money, higher-level officers and be generally pre-planned.

The annual illicit income generated from elephant ivory and rhino horn trafficking between 2016 - 2018 was estimated at US$400 (310 – 570) million for ivory and US$230 (170 – 280) million for rhino horn trafficking.

References

World Wildlife Crime Report Trafficking in protected species 2020. May 2020. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna

[ii] World Wildlife Crime Report Trafficking in protected species 2020

[iii] Wikipedia: Not all wet markets sell live animals, but the term wet market is sometimes used to signify a live animal market in which vendors slaughter animals upon customer purchase

[iv] All the above quotes are from the Animal Equality UK website: https://animalequality.org.uk/act/ban-wet-markets?

[v] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) World Wildlife Seizure database

[vi] Wikipedia: Agarwood, aloeswood, eaglewood or gharuwood is a fragrant dark resinous wood used in incense, perfume, and small carvings. It is formed in the heartwood of aquilaria trees when they become infected with a type of mould (Phialophora parasitica)

[vii] The Herald. 29 September 2021