Home >

Mashonaland Central >

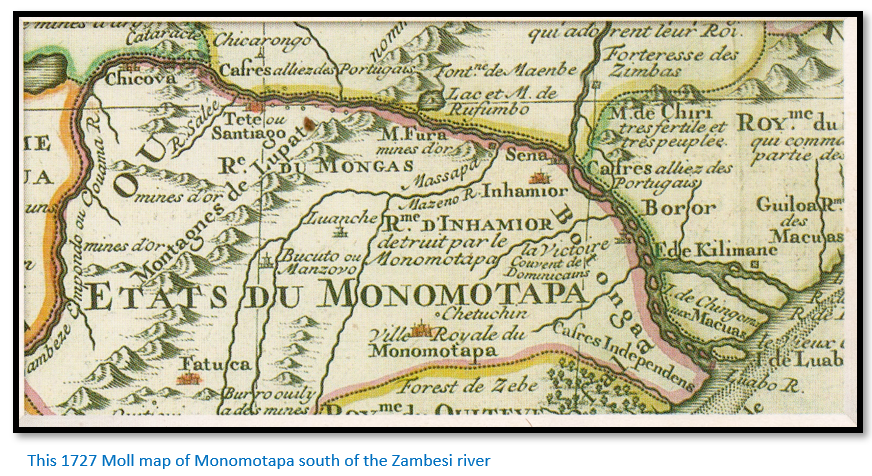

Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa)

Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa)

The background to the military expedition

J. Boxer writes that there was no doubt that in seeking to expand their seaborne empire that the Portuguese hoped to combine trade with an evangelical mission: “Whatever motives had originally inspired the Portuguese voyages of discovery after the capture of Ceuta (in 1415) Christians and spices were what they chiefly hoped to find when they actually reached India. This close association between God and Mammon formed the hallmark of the empire founded by the Portuguese in the East, and for that matter, in Africa and Brazil as well.”[i]

The Portuguese explorer, Vasco da Gama (1460-1524), was the first European to sail from Portugal to India. Praise for his achievement have long concealed the real reasons behind the 1498 voyage: “to invade, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens (Muslims) and pagans and other enemies of Christ; to reduce them to perpetual slavery; to convert them to Christianity; [and] to acquire great wealth by force of arms from the Infidels.” These actions were approved by various Papal Bulls, together called “the Doctrine of Discovery” (Dum Diversas, 1452; Romanus Pontifex, 1455; Inter Caetera, 1493)[ii]

The major reason behind these undertakings was to replace Arab control of the spice trade with Portuguese control. The military nature of these actions required extreme violence, with the Church’s approval, inflicted upon the Arabs and local native populations.

Father Monclaro accompanied the expedition and wrote a report which I have used extensively in this article and was translated by George McCall Theal.[iii] All quotes are from his report unless another source is referenced. On the general aims of the military expedition led by Barreto he says: “Of the intention of the king Dom Sebastian[iv] in this conquest - from what I could gather when I was in Almeirim preparing to come with Francisco Barreto, and afterwards in those parts from the orders and letters of his Majesty, his intention was to fulfil the obligation by which he and the kings his predecessors had bound themselves to the sovereign pontiffs to cause the gospel to be promulgated, by whose authority they have justly and righteously acquired possession of these conquests and their commerce. Secondly, to aid in meeting the ordinary large expenses of his kingdom and of India, and if our Lord should so please that wealth resulted therefrom, to conquer Africa. And because he had more favourable reports of the abundant riches of the realms of Monomotapa than were borne out by facts, or came within our experience, he determined to carry out what the king, his grandfather, and the queen, his grandmother, wished to attempt during their reigns. The unjust death of Father Goncalo da Silveira, whom the Monomotapa caused to be executed, being thereto persuaded and bribed by the Moors of those parts, was also another great motive. For these and other reasons, this expedition was ordered to be undertaken.”[v]

Bailey Diffie and George Winius (1977) further explain Portugal’s motives: “the mysteries of the Atlantic Ocean and the African coast challenged those adventurous in spirit. The young fighting class found a place to win honours and new lands. The religious saw an opportunity to convert infidels to Christianity. For the merchants and seamen there was opportunity for profits in a new era of trade. Although hailed as a “discovery,” the Portuguese were well aware of the lands of the Far East, but what they lacked was direct access to the region. Traveling the ocean route allowed the Portuguese to avoid sailing across the highly disputed—and costly—Mediterranean and traversing the dangerous Arabian lands.”[vi]

J. Mutero Chirenje (1935-1988) attributes the military expedition to a saying attributed to Vasco da Gama: “I seek Christians and spices” which seems to have been borne out by subsequent events.[vii]

Portuguese first contacts with Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa)

We know Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope and sailed from Malindi on the Swahili coast with a local pilot to Calicut and Goa in India in 1497-1498.

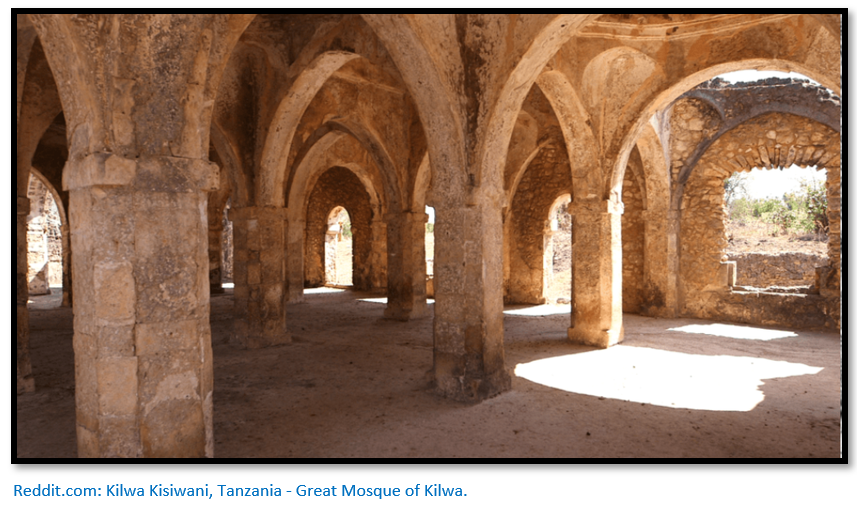

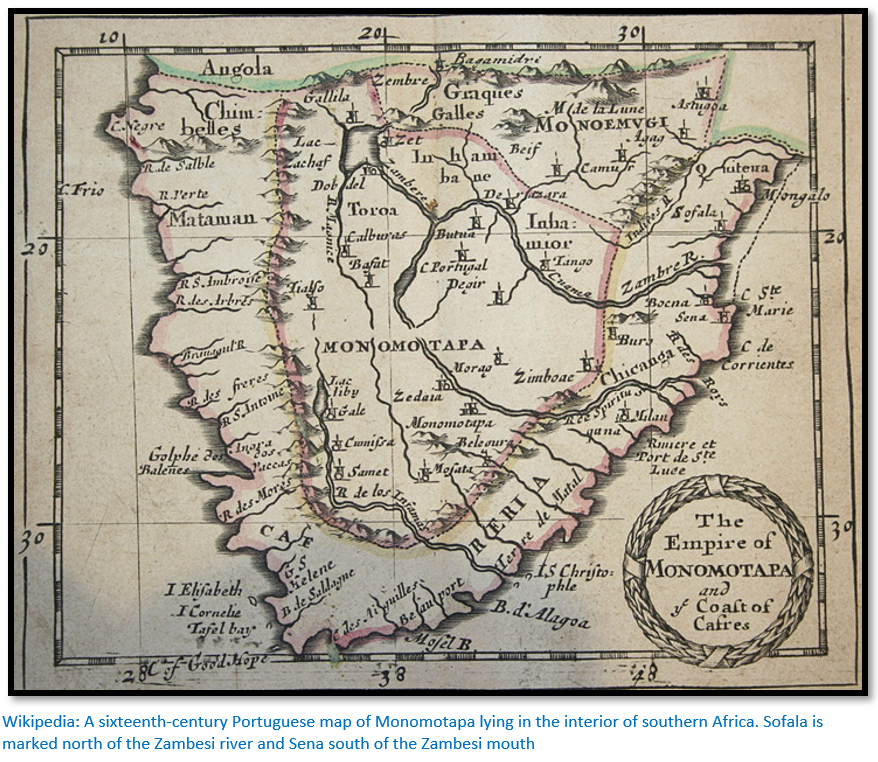

In 1489 the Portuguese explorer Pêro da Covilhã is believed to have been the first European known to have visited Sofala. His report to Lisbon identified Sofala's role as a source of Mwenemutapa’s (Monomotapa) gold from the fair at Manica.[viii] Sofala had arisen as a small trading post run by Swahili merchants in the tenth century connected to the interior by river-going dhows along the Buzi and Save rivers and to the Kilwa Sultanate by seagoing dhows. In the 1180’s it was seized by Sultan Suleiman Hassan of Kilwa and brought into the Kilwa Sultanate and became an important town on the Swahili coast.

In 1501 Sofala was scouted from the sea by the Portuguese Captain Sancho de Tovar and in the following year Pedro Afonso de Aguiar (others say Vasco da Gama himself) led the first Portuguese ships into Sofala harbour. Either Aguiar (or Gama) had a meeting with the elderly ruling sheikh Isuf of Sofala and agreed to a commercial and alliance treaty with the Kingdom of Portugal. This treaty was followed up in 1505 when Pêro de Anaia (part of the 7th Armada) was granted permission by sheikh Isuf to erect a factory and fortress. Fort São Caetano of Sofala was the second Portuguese fort after Kilwa, was built only a few months earlier, on the Swahili coast. For more information see the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

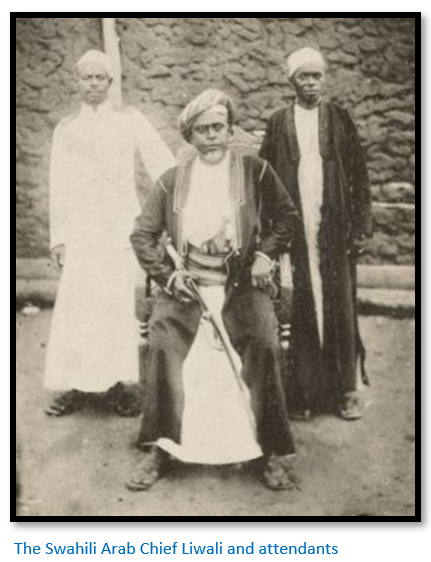

Swahili merchants were already well-established in Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa)

Swahili merchants travelled inland from Sofala and directly up the Zambesi river from about the tenth century onward.[ix] Arab writers of the 10th and 11th Centuries, which deal with the export of gold and ivory from Sofala, clearly demonstrate the existence of commerce between traders from the Manica area and elsewhere in the interior with the Swahili traders at the Coast. However it is difficult to assess how many were engaged in the gold trade, but clearly some were permanently resident at the principal gold fairs and at the Mwenemutapa’s court and had traded for gold and ivory for at least five centuries before the arrival of the Portuguese.

The Portuguese begin to explore and compete with the Swahili merchants

In March 1505 a Sofala clerk wrote: “A kaffir of the interior of Menapotaque [Mwenemutapa] was the first to come to this fortress and factory to trade gold for merchandise…namely…two yards of glazed Brittany cloth and two red barrets…beads”[x]

Antonio Fernandes made two journeys into the interior in 1511-12 and because he was illiterate described them to the clerk Gaspar Veloso. He reported the existence of stone ruins “now made of stone without mortar,” described the gold mines of Mbire and Butua [roughly northern Mashonaland and at Khami, near Bulawayo] and the gold fairs of the interior at which Swahili merchants were the main buyers.

The trigger for Barreto’s military expedition was the 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. on the upper Musengezi river on the orders of the Monomotapa, Chisamharu Negomo

Chirenje suggests Silveira: “was a pawn in a dynamic encounter between two mutually intolerant patterns of belief, on the one hand Shona religion…on the other a rather personalized Christian religion…which condemned all other religions as irrelevant…”[xi]

Silveira’s initial journey into the interior in 1560 with Friars Andre Fernandes and Luiz Froes was to Otongue, inland of Inhambane where he baptised 450 converts after an extremely superficial religious teaching. His report to Goa[xii] betrays his lack of cultural awareness: “I made a point of baptising a large number together immediately, because these people resemble children who like to act together and follow each other’s lead. They also resemble children as far as any intellectual impediment in receiving the faith is concerned for none of them have any kind of Idol the film of worship resembling idolatry.”

Silveira now had hopes of converting the whole of Southeast Africa to Christianity and he believed the best way of achieving that was to convert the King of Monomotapa following the Latin maxim cujus regio, ejus religio meaning “whose realm, their religion” – the religion of the ruler was the religion the people followed.

His journey from Mozambique Island to the upper Musengezi river to meet the Monomotapa Chisamharu Negomo can be traced by map in the article the 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Here he was given a warm welcome, but his refusal to accept gifts of women, gold, cows and land puzzled the young Chisamharu Negomo and made him suspicious and he is reported to have said: “it is not possible that a man who cares for none of these things which are offered to him, the desire for which is so natural to all, should be like other men, but he must have been born of the herb and had his origin in them.”[xiii] Another barrier created through cultural insensitivity.

Again, Silveira resorted to mass conversions of the ruler, his family and 300 of his subjects, but with very little religious instruction and therefore they had little understanding of what was entailed. Luiz Froes reported that: “the father (Silveira) was so beloved by the King and all the nobles that they never left him… All people, noble and plebeian, wished to become Christian subjects.”

Clearly however, Silveira made some serious misjudgements. First he equated the communal living of Shona society as ‘childlike behaviour,’ secondly he assumed that a very superficial religious explanation of Christianity would be sufficient for these ‘children’ and thirdly that mass baptisms were the solution.

This is shown in another very relevant way in his dealings with the Monomotapa Chisamharu Negomo, then a young man of about 16 years old. The rulers’ counsellors saw a picture of Mary, the mother of Jesus, in Silveira's hut and told their ruler, who asked to have it. Silveira told him that it was the mother of God and all the Kings and Emperors of the earth were her servants before presenting the picture to the ruler. Subsequent, Mary appeared in the ruler’s dreams four times speaking a foreign language. Silveira told him the divine language was intelligible only to converted Christians.

But Chirenje points out this threatened Negomo’s authority as it made him subservient to Mary, this woman God. At the same time the Swahili merchants resident at the Negomo’s kraal realised their positions were threatened by the rulers’ baptism and alleged Silveira was: “a traitor who brought heat and hunger and had with him a dead man's bone and other medicines to take the country and kill the King.”

Negomo was convinced. On the 15 March 1561 once Silveira was asleep, his hut was rushed and he was killed him in the traditional way a muroyi, or sorcerer was killed. He was thrown on his front by the Mucurume, the Monomotapa’s right-hand man and another four men lifted him up by his arms and legs. A rope was looped around his neck and pulled from both sides by two more men; blood poured from his nose and mouth and he was strangled until death. Then his body was dragged with a rope to the nearby Musengezi river and thrown in. He was just 35 years old.

The implication for the Portuguese of Silveira’s death

Converting the Monomotapa had been conceived as a key way to tempt the ruler away from the Muslim faith and the influence of the Swahili merchants. Portugal wanted to be at the source of the gold, the mines of central Mashonaland and Silveira’s death was a serious impediment to their plans. They believed the wealth that could be generated would pay for the spices of the East.

Silveira’s death at the hands of the Monomotapa and the departure of his assistants provided the raison d’etre for Portugal to restore its influence using force and “in 1569 King Sebastian of Portugal submitted the question of propriety, according to international law, of waging war against Negomo to a commission of lawyers and theologians called the Mesa da Conscencia.”[xiv] Clearly the court heard only the Portuguese version of events and quickly came to the conclusion that the King of Portugal might justly make war on Negomo as he had murdered Silveira, robbed Portuguese nationals of their property and allowed the Swahili Arab merchants to live in Mashonaland.

The court declared: “having seen and examined these documents and reports of many persons, from which it is proved that the emperors of Monomotapa frequently command their innocent subjects to be killed and robbed and are guilty of many other wrongs and tyrannies for slight causes and that they ordered several Portuguese, peaceably engaged in trading, to be killed and robbed and that one of these emperors ordered the Father Dom Goncalo to be put to death.”

Sebastian of Portugal was authorised to prosecute the war with “an upright intention of spreading the gospel.”

A military expedition is authorised in 1569

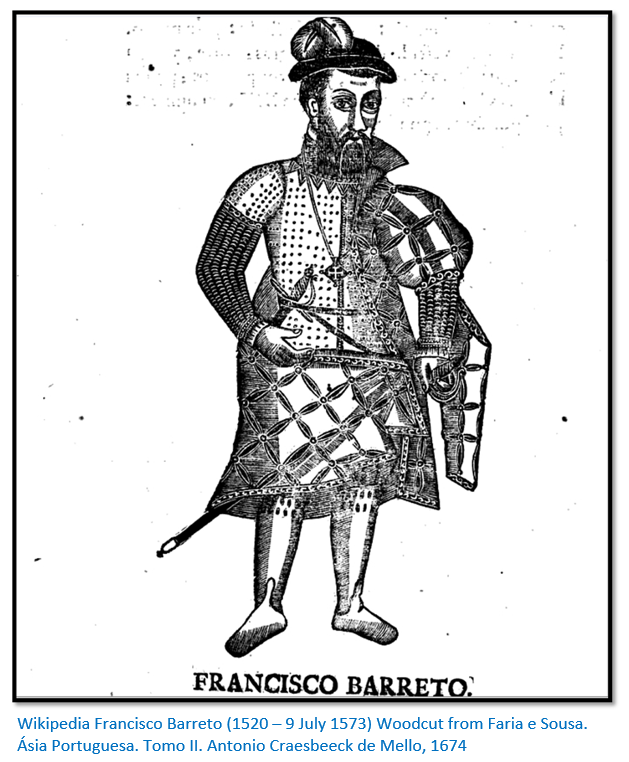

King Sebastian I appointed Barreto in command of the expedition to Mwenemutapa with the principal aims of seeking revenge for Silveira’s death and locating the empire’s legendary gold mines. The historian Diogo de Couto believed that Portugal required a source of gold and silver bullion similar to that being found by Spain in Mexico and South America.

Attacks were to be mounted against both the Shona, ostensibly for revenge after the killing of Silveira, and the Swahili merchants to displace them and disrupt their gold and ivory trade with the Mwenemutapa. In 1505 Manuel I had instructed Francisco De Almeida, the captain major at Sofala not to sell firearms to the Swahili Arabs to give the Portuguese an added advantage in any future fight.

On the political and religious side Barreto was given instructions to: “undertake nothing of importance without the advice and concurrence of the Jesuit Francisco Monclaros.”

King Sebastian’s mother, Joanna of Austria gave the Fathers gifts for the Monomotapa: “And when the fathers went to take leave of her, she gave them several objects of devotion from her chamber for the Monomotapa in case he should be converted, among which was an Ecce Homo as big as the quarter of a sheet of paper of the largest size, of a very strange fashion and material. It was made of birds' feathers so fine in colour and so skilfully set that they depicted the image of Christ in that suffering, very naturally. This picture was sent as a great present to his Majesty from the Spanish Indies. There was also a crucifix of ivory, of medium size, very well carved.”

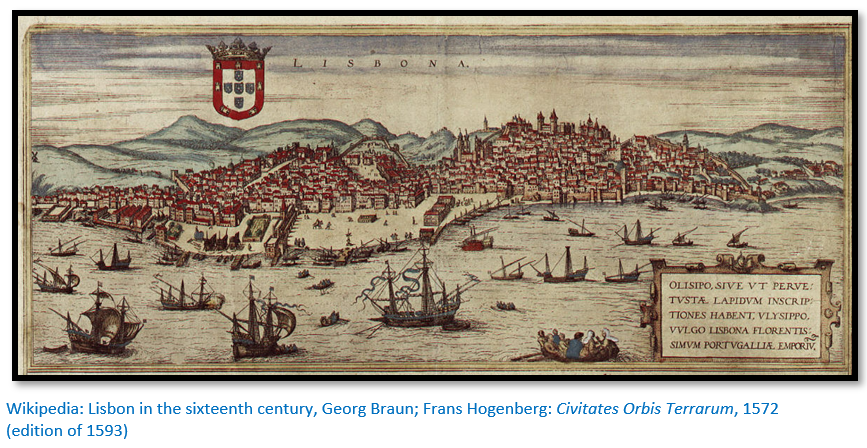

The expedition leaves Portugal

Barreto with the title bestowed on him of Conqueror of the Mines with his three ships and 2,000 men set sail from Lisbon on 16 April 1569.

Monclaro reports: “The fleet began to make ready in the port of Lisbon. It consisted of three ships, one of six hundred tons, in which the chief captain was to sail, and the other two small, from Villa de Conde, of about one hundred and fifty tons each. In one of them went Vasco Fernandes Homem, a nobleman who was formerly master of the order of Santiago, which office is now held by the king, with his son Antonio Mascarenhas. In the other ship went Lourenco de Carvalho. Many persons were desirous of taking part in this expedition, both on account of the hope of the gold and riches expected from it, and because of the chief captain and so many noblemen.”

The soldiers were veterans of previous colonial wars: “Barreto took with him many soldiers well trained in Africa, many servants of the king, and other soldiers who had served with him in the galleys. In the opinion of many it was the best and most illustrious company that ever set out from the harbour of Lisbon…

…We set sail with great sound of trumpets and other warlike instruments, with which it is usual to take leave, and while saluting the churches of the saints which were visible from the sea as we passed by them, it happened that in saluting our Lady of Help a cannon burst, and one of the pieces struck the hat of Francisco Barreto and another the main brace, passing among the people without injuring any.”

On reaching Brazil they heard there had been a great plague in Lisbon and amongst the dead was Francisco Barreto’s wife Dona Beatrice de Ataíde. They sailed from Brazil at the end of January 1570.

Arrival at Mozambique Island

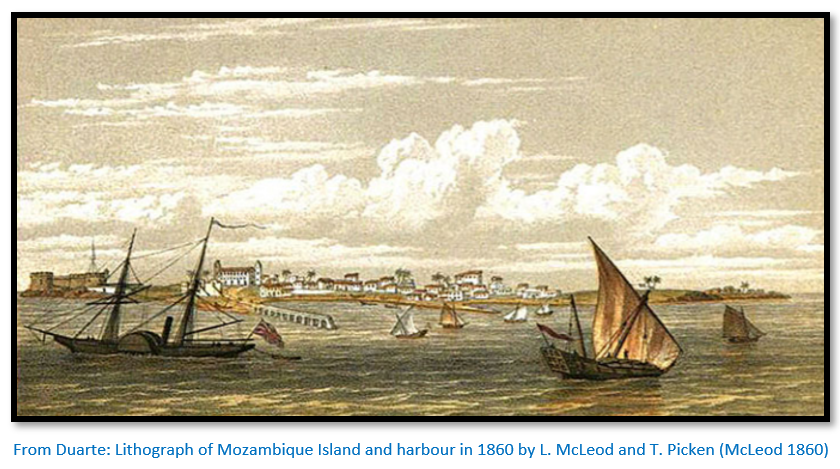

The port and safe refuge was reached after a stormy passage: “With these pastimes we reached the port of Mozambique on the 16th of May 1570, nearly seven hundred souls, of whom five hundred and fifty were soldiers, such a picked company as had not been seen in the island of Mozambique for many years.”

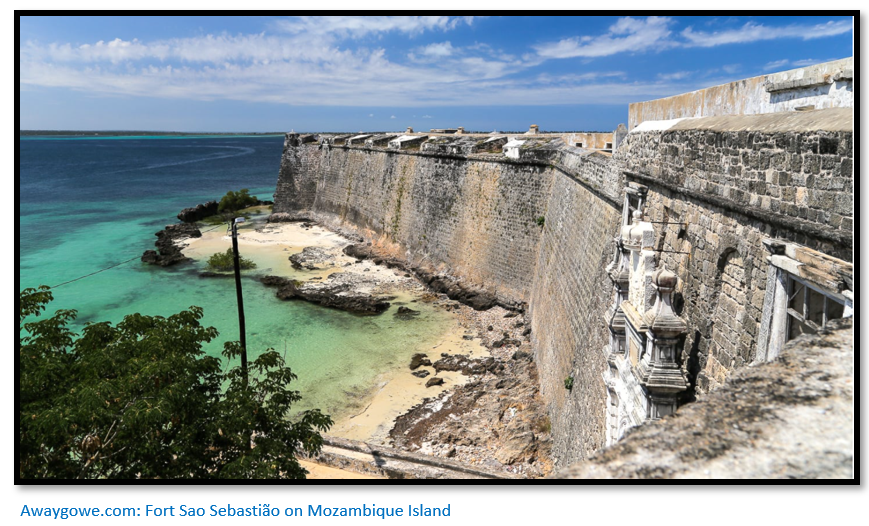

Mozambique Island

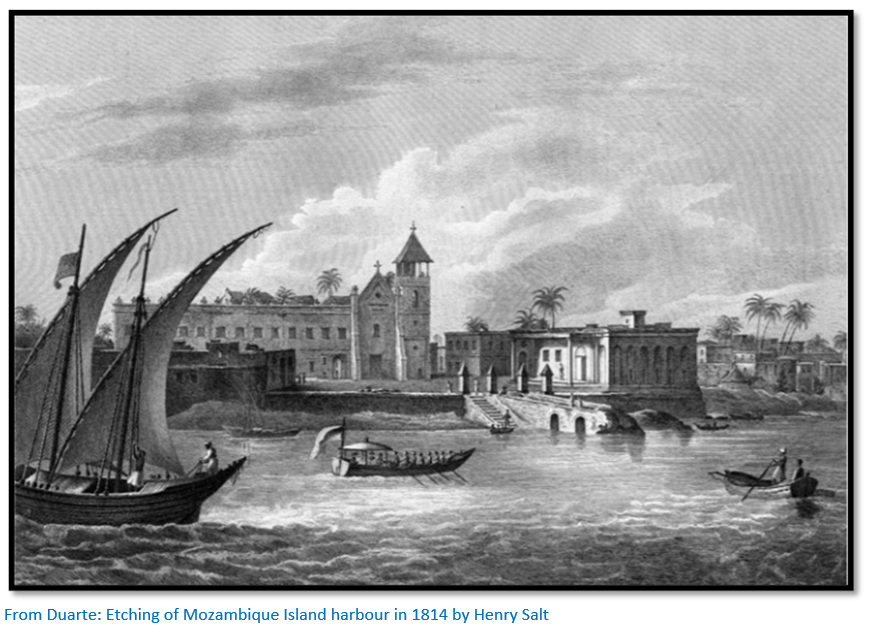

Here is Monclaro’s description: “The island of Mozambique is very small, being scarcely a league in length, and so narrow in the middle that a stone may be thrown from one side to the other. It is of sand and covered with palm groves. There is no fresh water, except in some pools which they call fountains, where it is brackish. That used for drinking is brought from a distance of five leagues. It has an ancient fortress, but a very fine new one is now being built, on which large artillery which we brought from the kingdom will be mounted. There is a ruined Moorish village. The Portuguese village has about a hundred inhabitants, and of people of that country, namely Kaffirs and Indians mixed, there are about two hundred. It is about half a league distant from the mainland. It is healthier at present, because of different refreshments which are sent from the gardens on the other shore, and a certain quantity of oranges and lemons. Many deaths take place here from the ships which arrive from the kingdom. The captain of Sofala resides here, it being a more convenient port for all the coast of Melinde. The currency is gold dust, the least quantity or weight being half a vintem…Here we remained a year and a half without Francisco Barreto proceeding on the expedition.”

From Mozambique the Portuguese undertake a military expedition to conquer the Comoros Islands

“We asked the chief captain to proceed in the meantime to the islands of Comoro, and to conquer them for the crown, because they would be very advantageous, and to build a fortress there and put a strong garrison in it. These islands are eighty leagues from Mozambique. The captain answered that he thought it would be better to go to the coast of Melinde, and from it proceed against the islands; and so, in the beginning of the following October we set out in the small ship of Vasco Fernandes, in which there went nearly three hundred soldiers, he going as captain.”

The expedition travelled to Kilwa. “The city was formerly very large and prosperous, the houses were all of stone and lime with tiled roofs, but it was twice destroyed by our people because of the treachery of its inhabitants.” Then to Zanzibar: “It is about twenty-five leagues in length and ten or twelve in width. It is a very fertile island, and abounds with yams, fruit, and other produce of the country.” Then onto Mombasa: “It has a very good and safe port, which is most convenient; it is about two leagues in circumference and has its Moor [ruler] like the others and a large and populous city. Here for the first time, I saw large vessels drawn up on shore, all sewn with cocoa-nut fibre, without nails of any kind.” And then to Malindi: “Thence we went to Melinde, which is also a Moorish city, in a very ruinous condition, for the sea has encroached upon almost every part of it, but what remains standing shows that it must have been very noble in ancient times, as is related in the histories of India. The Moors here are very friendly with the Portuguese, and in features and appearance in no way differ from ourselves. Many of them speak Portuguese very well, our principal trade with them being carried on here, and it being the residence of the captain.”

From Malindi they reached Cambo (Lamu Island?) “A queen governs here, who is very friendly to the Portuguese, so much so that she exposed herself to great danger for their sake. Certain Turkish galleys and other vessels came into her port, and hearing that there were some Portuguese in the place, demanded them; but she refused to give them up, and rather provided for their safety and concealed them. The Turks thereupon worked great havoc in her country, and carried her as a captive to their fleet, with other Moorish women; but she, being upon the poop of a galley at night, threw herself into the sea, and escaped by swimming. And because she had endured this for us, our late king, now with God, commanded that she and her affairs should be cared for by all his realm of India, and that great consideration, should be shown to her. Francisco Barreto went to visit her with a large military escort, and in the name of his Majesty bestowed upon her many privileges and safe conducts to traverse the coast.” From here they visited Pate (Kismayo?) “It is about twelve leagues distant from the city of Cambo, along the coast. It has a bad port, and at low tide the sea retires more than three leagues, and with the rising tide the water rushes in very furiously. Nevertheless, it has a large commerce with Mecca and other parts. The city is very large and has many fine edifices. Its Moorish priest was the chief of all on the coast... When we arrived, we found the country deserted by all but the king and principal Moors, who begged for mercy, which was readily granted upon their paying the soldiers twelve thousand cruzados, partly in money and partly in cloths and provisions.”

From here they returned to Mozambique Island without getting to the Comoros Islands

The fruitless expedition failed to achieve its objectives and took eighteen months: “During this sojourn in Mozambique and on the coast of Melinde, which occupied rather more than a year and a half, over one hundred men of the expedition died.”

The expedition leaves Mozambique island

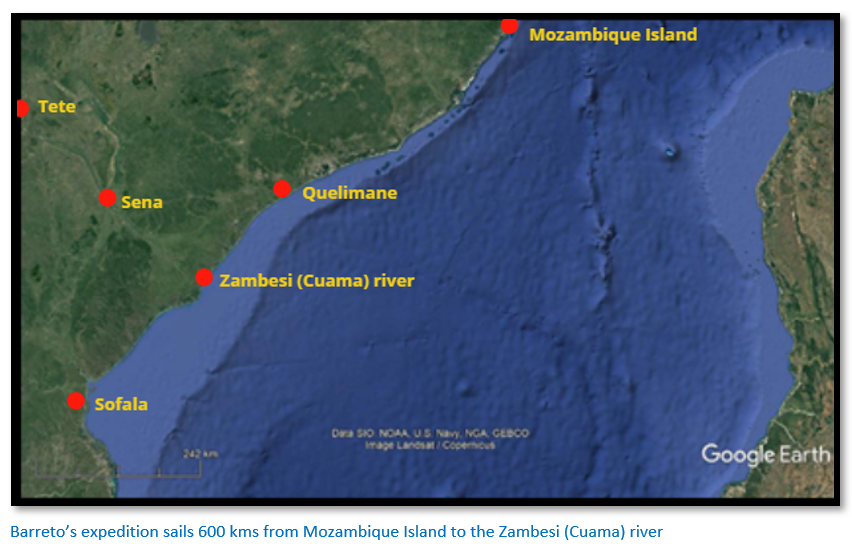

Barreto wanted to take a route to the gold mines of Manyika from Sofala, but was overruled by Father Monclaro who insisted the expedition take a route up the Zambesi [Cuama] river via Sena as he believed this would enable the expedition to march to the upper Musengezi river where the Jesuit Father Gonçalo da Silveira had been martyred by the Monomotapa, Chisamharu Negomo in 1561.

Monclaros writes: “Thus in November 1572 we set out upon our expedition, in nearly twenty small vessels, a caravel, and a small galleon used in the trade to Cape Correntes, which being a lofty ship steered a straight course for the river of Cuama at the mouth of ----. The small vessels proceeded along the shore, putting in at many ports, the first of which was the islands of Angoxa.” [Angoche]

Duarte[xv] writes: “Slightly earlier, in 1570, the Portuguese commander Francisco Barreto organized a military expedition to the kingdom of the Monomutapa south of the Zambezi using local traditional crafts. Leaving behind the huge and difficult to manoeuver Portuguese naus in which he had sailed from distant Portugal moored at Mozambique Island, he transported his army of 650 soldiers, horses, canons and supplies down the coast to the mouth of the Zambezi in 20 hired local ocean-going ships, pangayos, and proceeded on foot along the river followed by 20 luzios that carried all the supplies.[xvi]

The expedition proceeds up the Zambesi (Cuama) river by boat

Monclaro writes of the local people: “There is no king upon this coast, except those who are called fumos, who are the chiefs of the country, some great and some petty, and always at war among themselves. There are some half-caste Moors among them, and the whole of the coast is infested by this infernal race...

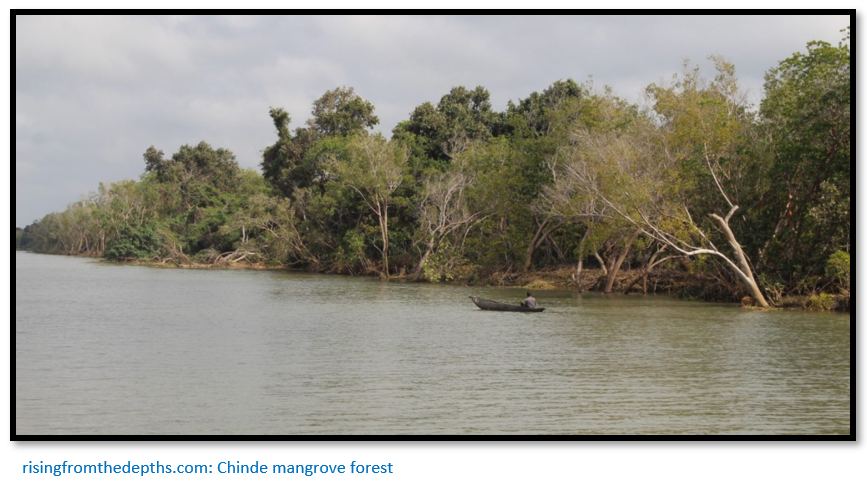

…From this river of Quilimane, we went to the mouth of another arm, which is called Linde, [Chinde] and passing by the other mouths by which the great Cuama enters the sea, we reached the last, which is called Luabo. These first and last mouths are thirty leagues apart. The country here is very marshy, low-lying, and unhealthy.”

The expedition sailed up the Zambesi (Cuama) river in November 1571, armed with weapons and mining tools and arrived at Sena on 18 December.

Strange and new local animals were seen as they went upriver: “There are many hippopotami in this river, very hideous and badly proportioned animals; their heads are like a horse's, but much larger…Francisco Barreto fired at one with his arquebus in the breeding time and struck it on the head. We heard from our boat the sound of the ball when it struck, and, as others say, it bounded off without doing much damage. The animal was stunned, but made several dives, and came up farther down the river alive and unhurt, though stunned. When they rush from the land to the river their course is very furious, and they unheedingly overthrow and break everything they meet, even good sized trees.”

“One Jeronimo Dalmeida, a Portuguese soldier who was fifteen years in those parts, says of these alligators that he saw one dead in the river, which was sixty feet in length and ten in width, according to his measurement. The emperor of Monomotapa is so cruel that when he wishes to judge a cause he commands the accused to swim across the river, and if he succeeds in doing so without being devoured by the alligators he is held guiltless, but if not he is devoured, and that is his punishment.”

Progressing up the Zambesi river

“We proceeded up this river during sixteen days, and when the wind failed we were towed along. A canoe went first with a cable many fathoms in length and an anchor or large grapnel, this canoe was rowed as far as the cable would permit, when the anchor was dropped, those in our vessel then hauled on the cable until we reached the other end, when we cast anchor, and the canoe went on again. In this manner, and also by towing, we made the greater part of the journey.”

The expedition reaches Sena

“Francisco Barreto reached Sena, which is a small village of straw huts in a thicket, in the year 1572, on the feast of our Lady of ----. The country is ruled by a Moor, the son of Mopango, a great chief, but a vassal of Monomotapa, who succeeded to the kingdom while we were there, through the death of his father. He often came to Sena for love of the wine and cloths which the Portuguese gave him. Here our people disembarked, a select and well equipped company, more in the humour to fight Turks or other skilled soldiers than Kaffirs. In all they numbered more than seven hundred arquebusiers, with many good officers, and soldiers of long experience in war.”

Fort St. Marcel at Sena was to be built in the interior of Mozambique serving as a base camp for the penetration into the empire of Mwenemutapa; at the same time, it controlled the Zambesi river, which was the major route of trade to the interior after the decline of Sofala. The first fortress, made of rammed-earth and wood was succeeded by the stone fort, built at an unclear date between 1572 and 1590 and described for the first time by Friar João dos Santos: “This town includes a stone and lime fort, outfitted with some heavy and small pieces of artillery, sufficient for its defence, where the captain, appointed by the captain of Mozambique, lives. The fort encompasses a Church and trading post.” It was in ruins as early as 1618 and partially rebuilt in 1704, with maintenance in charge of the townspeople, each forced to look after a bastion, or a section of the wall. The fort plan was square, with four bastions, made of adobe of clay and covered with thatch, armed with 14 artillery pieces and a garrison of 50 men.[xvii]

The Swahili Arabs are suspected of poisoning the Portuguese at Sena

Monclaro wrote: “In Sena the Moors began to wish to kill the Portuguese secretly with poison. There came large oxen from the interior, so handsome and tame that those of this kingdom cannot excel them, and these were bought in the interior for beasts of burden and provision for the soldiers. But the Moors sent in the mornings and put poison on the grass used for their pasture, and made the governor believe that when any died it was from the effect of a certain noxious herb which grew in the country. They also made the inhabitants believe this, to the end that there might be no cattle in that country, and that it might not be occupied by our people; and even to this day those in Sofala live in this error. The oxen died suddenly, though fine and in good condition, and were given to the soldiers for food. When I saw this I always suspected the cause, and maintained that it was poison, so that the governor was vexed and cast black looks upon me when I spoke to him about it.”

Barreto’s soldiers take revenge on the Swahili Arabs at Sena

“When we arrived there the land began at once to yield what it has, namely much sickness. During the time we remained there, which was nearly a year, more than a hundred persons died, and this before we advanced into the country; and the greater number of the people fell sick. Ruy Nunes Barreto [the brother of Francisco Barreto] fell ill of poison, which was given him by the Moors, of which he died, for it is their custom to administer it, and thus to continue secretly killing our people. And though Francisco Barreto had an order to eject the Moors, as he made known to the Monomotapa, because of the feigned honours they rendered him at his coming and ever after, he did not put it in force, not considering the evil they did him in secret.

But at last, when he became aware of their treachery, Francisco Barreto immediately sent his captains and their men to arrest the Moors, who lived in houses apart from the town and on the other side of the river, at a distance of one or two leagues, which the soldiers did very willingly, for besides being revenged on the Moors, most of the gold which they had fell to their share, of which more than fifteen thousand miticals went to the king.

They arrested seventeen of the principal men, among whom was the sheik and one of the plotters of the death of Father Dom Goncalo. Those were condemned and put to death by strange inventions. Some were impaled alive; some were tied to the tops of trees, forcibly brought together, and then set free, by which means they were torn asunder; others were opened up the back with hatchets; some were killed by mortars, in order to strike terror into the natives; and others were delivered to the soldiers, who wreaked their wrath upon them with arquebusses.”

Father Monclaro believes no good will come of Mozambique

“As to the introduction of Christianity, there is very little hope, for the people do not understand what it is to be a Christian. They are so wrapped up in their own customs and the pleasures of the flesh, that they know nothing of the soul, which they cannot see, and they think that to be a Christian has nothing to do with the next life, but simply means to be a friend of the Portuguese…Therefore, I conclude that this land is a sepulchre[xviii] for Portuguese.”

Barreto sends gifts to the Mwenemutapa

“Francisco Barreto sent an embassy and rich presents to the Monomotapa by a Portuguese inhabitant of Sena [Miguel Bernardus] who had already been at his court, which they call Zimbaoe, distant two hundred and fifty leagues from Sena, where are the mines of Masapa from which they often come to trade in Sena. The ambassador set out, and died on the way, being drowned in the river in a canoe. The message sent by him was that we had arrived, and that the governor wished to treat with his highness of matters of importance and of great advantage to himself and all his people, on behalf of the most great, high, and mighty Dom Sebastião, king of Portugal and of the sea, and of India, his master, and to that end he sent to him to treat of peace and friendship, and that the men he had with him were to clear the briars from the roads and open them for the commerce of our people with his lands, and that in order to send an embassy he asked for an ambassador, which they call mutume.”

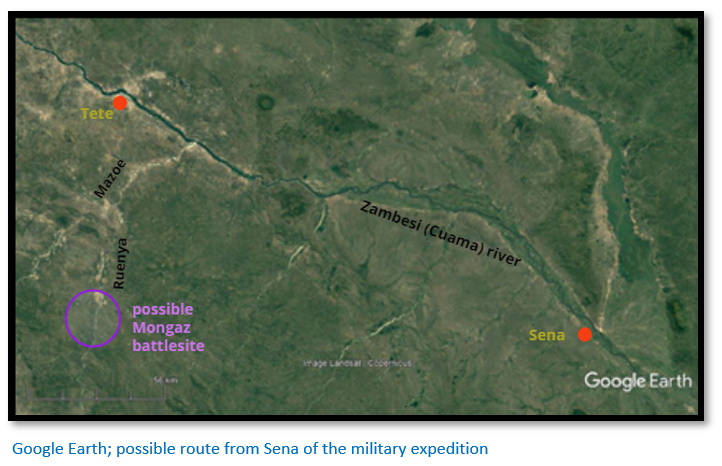

The military expedition begins its march from Sena

“Seeing (as I have said) that the ambassador delayed so long, Francisco Barreto resolved to proceed on the expedition at the end of July 1572, and we marched along the river, upon which we had more than twenty boats laden with provisions, merchandise, and ammunition. On land with our company, we had twenty-five waggons drawn by oxen of the country, as big as the large oxen of France and very tractable. These cattle came (as I have said) from Butoa and escaped the poison of the Moors.

The expedition had the following military sections:

(1) Under Vasco Fernandes Homem’s son - two hundred arqubusiers

(2) Under Antonio de Mello - a hundred and fifty men

(3) Under Thomé de Sousa - a hundred and fifty men

(4) Under Jeronimo d’Aguar - a hundred and fifty men

The total number of soldiers was about six hundred and fifty trained men. All these bands had their officers to command them, veteran soldiers well skilled in warfare.

We began our journey, keeping along the river; we travelled slowly, about a league and a half a day,[xix] always keeping in our ranks, with a vanguard and rear-guard, which the captains took in turn day by day, and thus when the governor went first, the colonel kept in the rear, and so on. On the river was the fleet of boats with many sick;[xx] and when a soldier fell ill he was embarked wherever we met the boats, for sometimes we were several days without seeing them, on account of the windings of the river and the evenness of the ground. Generally, however, we all encamped together on the bank of the river. At night we had watches and rounds, and many times the colonel and the governor visited them and chastised the negligent.

The Mongas are attacked and defeated

We had many false alarms from the Kaffirs as we went on, for these people are the Mongazes, feared for more than a hundred and fifty leagues on both sides of the river, and more cruel and dreaded than the Turks in Italy. Francisco Barreto rode a horse which was one of those that escaped the poison at Sena, always clad in a thick coat of mail, attending on every side to the good order of the camp. Besides all these, there were more than two thousand slaves with the baggage, but the waggons were an incumbrance, because they travelled so slowly that it took us a month to cross the fifty leagues[xxi] between Sena and the gates of Mongaz.

50 English leagues is 278 kms, in Portuguese 50 légua or legoa is 309 kms. The Mazoe river after its confluence with the Ruenya river is the major southern tributary and flows into the Zambesi approximately 210 kms above Sena. This is probably where Barreto left the Zambesi for Mongaz territory. After the battle Monclaro writes: “…to take the road to the bank of the river, above the island of the sick, from which point we had penetrated the country ten or twelve leagues in a straight line, but about twenty-five leagues by having shaped our course like a bow.”

On arriving there, as our intention was to destroy the Mongazes, in order to leave the river and enter their lands, it was necessary to place the sick, who numbered more than eighty, upon a little island, one of the principal men, named Ruy de Mello, a native of Evora, remaining as their guardian and captain, he being also sick and wounded by some wild buffaloes which he met when he was alone on horseback. We were near the lands of Mongaz, without entering them, for eight days, resting from the fatigue of the journey and arranging for the safety of those who were to remain on the island.

The cause of the dispute with the Mongaz

They are very warlike and great thieves and highwaymen, and from the cruelty with which they treat those they have conquered they are greatly feared on every side. They killed and robbed many Portuguese, and our people who were in those parts revenged themselves upon them, twenty of them coming down the river from Tete[xxii] landed and killed some of them, and burned I know not how many villages. The negroes, to revenge themselves, went to Tete - which was deserted by our people, they having gone to obtain merchandise from the vessel which was at Sena - and attacked the Christian female slaves and children, killing about seventy persons. This happened a year or two before our arrival, and for these and other evils they had wrought it was very important not to leave these enemies so close behind us without subduing them.

Invasion of Mongaz territory

When we were ready to leave the river and enter the country and had made the best arrangements we could for the sick upon the island, we set out upon our journey, with the additional number of Kaffirs and about five hundred Portuguese. As we penetrated the country the people began to fall sick, as many did every day, and after two days’ journey, in which we had travelled about four leagues, it became necessary to send thirty sick, with horsemen and soldiers as their guard, back to the island…

When we had crossed the river, which was about half an hour after midday, because of the extreme slowness of the waggons upon the road, we caught sight of a few men who were within two musket shots of us, raising a great cloud of dust, whirling sticks with buffalo tails attached to them, which they carried in their hands, and making other demonstrations as of men who were waiting us in the field. The horsemen pursued them and put them to flight, and it would seem that they were spies.

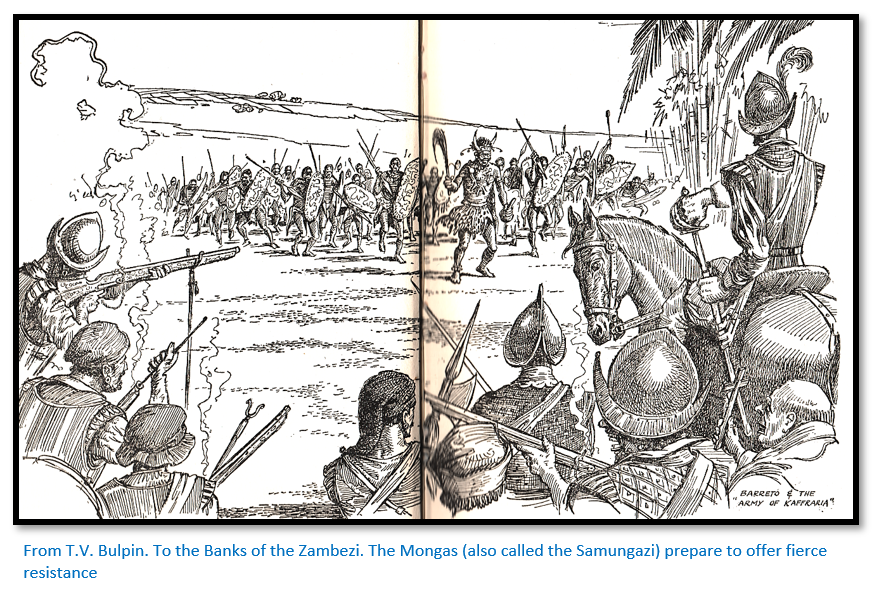

Of how we fought the Mongazes and the victories which our Lord gave us over them, and how we conquered their lands – the first battle

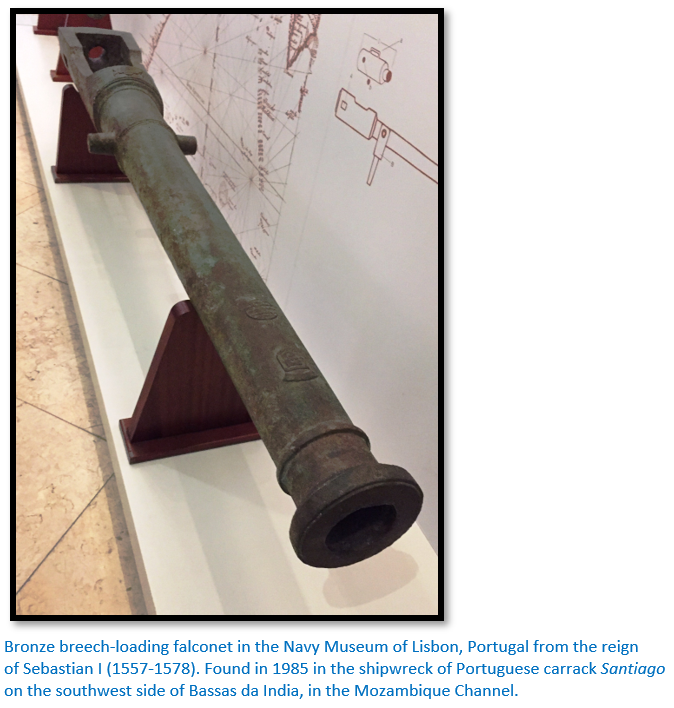

The next day at dawn we began our march in good order, the horsemen with some negroes acting as scouts, and the companies going two before the waggons, two on the sides, and one behind, with parties of arquebusiers thrown out, so that the baggage was in the middle. Francisco Barreto led the van that day, and I went before with a crucifix, which I raised as a standard after we had sight of the enemy. Here also went the royal standard and two pieces of artillery, namely a swivel falcon and a demi-cannon, which were of use that day.

We had sight of the enemy on a level plain, although in many parts it was covered with grass and tall reeds. They seemed to be about ten or twelve thousand men. Their light parties were drawn up on either wing, and the heaviest force in the middle; and they threw out companies of slaves on either side, and had many in ambush, who were so well concealed that when they began to discharge their arrows they fell close to the royal standard, but as the wind was against them they came with less force. Against these skirmishers two squadrons of soldiers advanced, who put them to flight with their arquebusses.

Meanwhile the main divisions were drawing near, and when they had approached within range of our guns, both pieces were fired among them, killing fifteen or sixteen, and at the same time our horsemen with some soldiers and all our slaves attacked them with loud cries, and put them to flight...

Near the field of battle was the kraal of a chief, a great warrior, named Capote, who guarded the entrance of the lands of the Mongazes and made great efforts in defence of his village. The guides were leading us to the said village, as we had decided to camp there, because there was water, though very bad. As we were entering it in the same order, the Kaffirs returned to defend it, attacking us in the rear, and as this was the post of the company that contained the fewest Portuguese, I went there with a crucifix, by the governor’s leave, to encourage them in the fight, which the enemy sustained very vigorously, attacking our people and darkening the air with arrows. They advanced in the form of a crescent, and almost surrounded us on every side. The colonel ordered no one to fire till they drew nearer, that having closed in we might attack them with heavier loss; and this enabled them to wound more than twenty-five of our men, though not dangerously.

It was noticed that wherever I was with the crucifix, although the arrows were numerous, no one was wounded by them within ten or twelve paces of it; and looking up in some fear of the arrows I observed that though many seemed falling on my head, the Lord whose image I carried in my hands diverted them, so that they left as it were an open space, within which no one was wounded, although I was in the front, and they came with great force, the wind being now in their favour.

The discharge of the largest gun was attended by an accident. It was loaded, and just as the gunner had finished ramming the charge, a soldier fired his arquebus over the priming, which took light from the falling sparks, and carried away the arms of a Portuguese waggoner and wounded him in many parts of the body with the pieces of rock with which it was charged as well as the ball, and also took off the tips of two fingers from the gunner’s right hand. When this gun was discharged, our people fell upon the enemy, firing all the arquebusses and attacking them with great fury. They found a company of them in a thick wood, where they killed many of them and captured four of their standards, one of which was the figure of an ox at the end of a stick, one of an elephant, both stuffed with straw, and the others were like Indian hats. The chief Capote was also killed here. Another man was wounded by an arrow in the groin and died in a few hours. The two Portuguese were both confessed, and were the only ones killed, and none of the wounded died.

The second battle with the Mongazes

After three days, at dawn in the morning we made ready to set out, and were just leaving when there came like a great dust storm with loud clamour the army of Kaffraria and Mongazes, reinforced with a number which was said to be sixteen thousand men, and with greater intrepidity and noise of drums, and more confident of victory, for they had with them a wizard who by the spells he carried in a gourd, which I afterwards saw, had persuaded them that he would deliver us all into their hands, and that our nafutes, which are the arquebusses, would be of no use. As sure of victory, he made them bring many ropes made of the bark of trees, which afterwards served the soldiers as very good match for their arquebusses. These were intended to bind us with, and their war cry was Funga Muzungo! which signifies bind the white man.

Not to delay too long upon this matter, which has not much bearing on the subject, they attacked us four times that morning, and each time we repulsed them with heavy loss. They tried to break our ranks in eight different places. The smoke was so great from the arquebusses and artillery, for beside the guns before mentioned six small pieces which were in the waggons were also used, of which Francisco Barreto made himself the gunner, that the air was obscured so that we could not see each other, and this was increased as the battle took place in a valley, and there was no wind. At this the enemy was astonished, saying that we were great wizards since we could turn day into night.

As we afterwards heard from them we killed more than four thousand Kaffirs in these engagements, and many were wounded and maimed, who afterwards died. Among these was the wizard, a musket making him drop his gourd of spells upon the ground, with the loss of his jaw-bone. They made signs that they wished for peace, and sent their envoys for this purpose, who were astonished to see Francisco Barreto seated in a chair in time of war. He showed them small ceremony, ordering them to come to him where he sat reviewing his men, which he did well, like a good captain skilled in warfare. He granted them peace, on condition that they should send their ambassadors to the village, which was before us, or otherwise we would set fire to everything; and they fulfilled this condition, as will be afterwards related.

The Mongas are attacked and defeated

The three day battle in July 1572 between Barreto’s expedition and the ‘Mongazes’ put 650 arquebusiers, supported by cavalry and about 200 local auxiliaries against a force of 10,000 – 12,000 men armed with spears, bows and arrows. The Portuguese were in a square formation and used their arquebusses and light cannon effectively. Arquebus muskets could throw a bullet 1,000 metres or more and were considered deadly to 370 metres[xxiii] (400 yards)[xxiv]

A spirit-medium was killed with a shot from a falconet or light cannon as he carried out a ritual dance. The gunpowder smoke became so thick the Mongas thought day had been turned into night. Reported Portuguese losses were 2 killed and 60 wounded, they claimed to have inflicted 4,000 casualties.

According to Kerr, when the Mongas King sent his ambassadors to Barreto in hopes of securing peace, the soldier tricked them into thinking that the camels used by the Portuguese, creatures foreign to Mozambique, subsisted on flesh, leading the Mongas to provide the Portuguese with beef for the camels.

The Mwenemutapa submits to the Portuguese

When the news that the Portuguese had severely defeated Chief Mungazi was brought to the young Monomotapa Chisamharu Negomo, he surrendered without fighting. Father Monclaro reported that Negomo expelled all the Swahili Arab merchants from his territories and blamed them for the death of Silveira and gave some of his gold and silver mines to the Portuguese.[xxv]

The Portuguese suffer from lack of supplies and sickness and abandon the Zambesi route to Mwenemutapa

The Portuguese men suffered severely from malaria and dysentery: “Worse water cannot be imagined, for it was obtained in stagnant pools left from the winter, exposed to the sun, and covered with green slime; and even this was scarce.” Increasingly the soldiers fell sick:…”and besides the sick, the whole company was weak and enfeebled, and all fell ill afterwards… As there was no one to carry the sick, we were all obliged to go on foot and leave them the horses, and even Francisco Barreto carried the sick behind him on his horse.”

The expedition was now suffering from lack of food, although they had meat as the Mongaz had given them 50 cattle and goats as a peace offering. Barreto decided that in view of the difficult country ahead, with over 200 of his soldiers sick and the Mwenemutapa gold mines estimated at 200 Portuguese légua or legoa (1,230 kms) by those Portuguese traders at Sena who were familiar with the route, the expedition should return to Sena. At Sena would be provisions, the sick would recover, and they could wait for the trading vessels at Mozambique Island which arrived in February and March. From there they could sail to Sofala and travel to the gold mines at Manyika. This was acknowledgement that Barreto had been correct in his original choice of Sofala, and Father Monclaro had been wrong in overruling him.

So, they turned back to the Zambesi river which was reached by the beginning of October 1572. The wagons were burnt, the sick sent back by boat and the remainder begun the march back to Sena. They endured great hardships because of a lack of water, Francisco Barreto went down to Sena by boat leaving Vasco Fernandes in charge.

The Mwenemutapa sends his ambassadors

At Sena Barreto heard of the death of the ambassador he had sent to the Mwenemutapa, but also that the Mwenemutapa’s ambassador with 200 followers was coming to Sena. The ambassador was accompanied by officers of rank and on their arrival they announced that the Mwenemutapa wished to be a friend of the king of Portugal and that the road should be opened and trade begin between the two nations. Barreto’s conditions for peace were:

(1) All the Swahili Arabs should be expelled

(2) The Mwenemutapa should accept the Jesuit fathers

(3) Many of the gold mines in Mwenemutapa should be given to Portugal

The ambassador replied that they were agreeable to these conditions, that he would also send an army against the Mongazes.

Barreto appointed three Portuguese, with Francisco de Magalhaes in charge, to return with the ambassador to the Mwenemutapa with gifts and to receive his reply. Magalhaes died on the journey and was succeeded by Francisco Rafaxo; he and Gaspar Borges had an audience with the Mwenemutapa and returned to Sena.

Monclaro is rather scornful of the gifts from the Mwenemutapa to Barreto; eight bracelets of very fine gold wire which did not weight ten miticals.

The situation at Sena

The camp at Sena contained about 450 men, but there was a scarcity of cloth to trade for food and pay the soldiers. Fears had also been expressed at Mozambique Island at the quantity of cloth that would be required at Sena to maintain the garrison. Barreto decided he had to return to Mozambique Island taking Father Monclaro and 20-30 soldiers with him and leaving Vasco Fernandes Homem and Father Estavao Lopez in charge at Sena.

Antonio Pereira Brandao has been left as captain of São Sebastião fort on Mozambique Island; but his malicious reports and other matters had created much unpleasantness, so Barreto relieved him of his office. The trading ship arrived from India with the much-needed cloth and one of Barreto’s sons, Joao da Silva, and other stores and supplies needed by the expedition.

Barreto left Mozambique Island on 3 March 1573 for Sena taking his son with him, leaving the factor Goncalo Godinho as captain. In normal weather the voyage to Quilimane was accomplished in 4-5 days, but the contrary winds made the journey difficult, and the voyage took far longer. Two of the pangayos which carried ammunition, a quantity of saltpetre, and provisions were lost at sea. Here they heard the news that many had died at Sena, including two of the captains, Jeronimo de Aguiar and Antonio de Mello and all of the officers including the chief gunner, and Vasco Fernandes and the fathers were very ill. Father Estavao Lopez sent a letter saying not to sail up at the Zambesi at present: “the land being very full of infection, and the air pestilential.”

Barreto could not abandon his men and set off on 1 May 1573 from Quilimane and Sena was reached within 15 days. “Upon reaching Sena we found some soldiers on the bank of the river, about fifty in all, with the four banners, but no captains or officers, and they themselves in such a state that they could hardly stand. Passing by the hospital we saw the sick seated in the huts, looking more like dead men than living beings, but rejoiced at our coming. They had the arquebusses on the ground, and one who was a little stronger than the rest fired them all, for the others were unable to do it. It is a strange thing that there was not one man in good health: a very different spectacle from what was witnessed on the plain of Sena when we first arrived, and no one was able to restrain tears of sorrow for such mortality, as even of the eighty men who had come with the ships of the year fifteen hundred and seventy-two, and had joined the expedition, not five remained alive.”

Death of Francisco Barreto

“After our arrival at Sena, Francisco Barreto began to provide for all necessities in person, giving out preserves, clothing, biscuit, and other things which we had brought, and visiting all without and within the hospital; thus, some began to be convalescent. I [Monclaro] grew better of an illness from which I had suffered on the journey, but the new comers fell sick directly…”

Eight days after arriving back at Sena, Barreto fell sick, but not so badly that he was confined in bed. Then 7 days after this: “he was seized with colic and deadly vomiting, but his people said it was only a kind of indisposition to which he had been subject in Portugal. I went to see him in the morning and found his pulse imperceptible and dead and his arms and feet cold. I gave him the holy unction, he being still conscious, and sent for Vasco Fernandes Homem to come and see him before he died, for his decease was certain. He came and remained to assist him, though he himself was suffering from fever and ague nearly every day. Close upon midnight he yielded his soul to God, in a straw hut, and we could not find in his desk or elsewhere as much as a cruzado for his obsequies, or for the benefit of his soul.

The next morning, we buried him in the chapel of St. Marcal, where, as the body of the building was full of fresh corpses so that there was no room for him, it was necessary to make him a grave crossways along the altar, even this being wanting at his death to a man who had been so prosperous, and who had lived in India with such display…”[xxvi]

Then the second letter of succession was opened, as Pedro Barreto was already dead, which named Vasco Fernandes Homem to succeed as captain. Francisco Barreto’s son, Joao da Silva was also very ill and left for Mozambique Island, where he also died.

The ambassador arrives from the Mwenemutapa

When Barreto arrived back at Sena he learnt the ambassador had come and gone in his absence with the Mwenemutapa’s replies that:

(1) He would expel the Swahili Arabs

(2) That he had not used his sword against Father Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J; this had been done by the Moors and he would discuss admitting the Jesuit Fathers to his kingdom

(3) He would select gold mines for the Portuguese and also the silver mines which were not far from Tete and the Zambesi river.

He wished for peace and friendship with the Portuguese as he knew they were great warriors after defeating the Mongazes. Here Monclaro adds that despite the Mwenemutapa having an army of over 100,000 men they could easily defeat him, but for the disease, lack of food and natural obstacles of his country.

The Portuguese at Sena decide what to do next

The remaining officers numbering 30 met at the governor’s house and in view of there being only 180 men left and few supplies, 25 voted for a return to Mozambique Island and this was done; the fort of St. Marcel at Sena being left with a captain, soldiers and the remaining supplies.

Of the original 650 men[xxvii] under Barreto’s command, only 180 men managed to make it back to Mozambique Island. All hopes of finding a treasure of gold evaporated, only some trade in cloth and ivory was carried out.

On their return to Mozambique Island the Portuguese took revenge on the Swahili Arabs living in the vicinity on the mainland who were terrorised and killed. Their place in the commercial life of Mozambique was filled to some extent by Portuguese traders who married locally and became prazeiros (estate holders) of the lower Zambezi.

Homen leads an expedition from Sofala to Manyika

Barreto was succeeded by his deputy, Vasco Fernandes Homem, who led the remnants of the expedition and regrouped back on Mozambique Island. Once Father Monclaro had left by ship for Lisbon, a new military expedition to the goldmines of Manyika was undertaken along the original route proposed by Francisco Barreto from Sofala. The Manyika mines, when finally reached, seemed underwhelming and unlike the legends, with local natives only producing very small amounts of gold mostly from alluvial workings on the Revue and Pungwe rivers. After failing to find evidence of other goldmines, Homem abandoned the search.

Father Monclaro declared with some despair: “As to the introduction of Christianity, there is very little hope for the people do not understand what it is to be a Christian.”

Commercial prospects of Mwenemutapa

Father Monclaro wrote to Sebastian I on the commercial prospects for Portugal: “Your Majesty my draw a revenue from this country by leasing the river [Zambesi, known to the Portuguese as the Cuama] the profit of which will increase greatly from the trade in squares of calico [Machiras] which is now beginning. Gold will be current as it has ever been in large quantities and orders may be given to regulate the commerce. For this purpose, I say it should be leased, because the officials now draw all the profit; but if the trade is not carried on by Your Majesty, but by a lessee, something will be saved, and not so little but that the whole of this government may yield in gold, ivory, ambergris.”

The life of Francisco Barreto (circa 1520 - 9 July 1573)

Barreto was born in Faro, Portugal, in 1520, to Rui Barreto and Branca de Vilhena. He trained and served as a soldier in Morocco in his younger days. He was sent to Portuguese India in 1548 and appointed Viceroy at Goa in June 1555 following the death of the previous Viceroy.

Governor at Goa

In 1557 Barreto fought with Adel Khan, King of Visapur at Ponda in central Goa and defeated his army. He also negotiated to gain Daman, a coastal city north of Goa, which proved unsuccessful. He defeated the Rajah of Calicut and was preparing a fleet to capture the Aceh sultanate in the north of present-day Sumatra when he was recalled to Portugal.

Return to Lisbon

After 11 years in Goa Barreto left on board the Aquia on 20 January 1559. The ship was severely damaged in a storm and arrived at Mozambique Island for repairs. The ship left on 17 November 1559 but sprang a leak and was forced to return. Barreto returned to Goa before leaving once more on the São Gião and arriving in Lisbon in June 1561.

In 1564, King Phillip II of Spain requested Portuguese assistance in capturing Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera, an island off the coast of Morocco. Barreto was in command of a fleet made up of a galleon and eight caravels alongside the Spaniard Garcia de Toledo and the combined navy took over the island's fort in two days.

Military expedition to Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa) in 1569

This part of his life is covered in the main text and ends with his death at Sena on 9 July 1573.

References

Ricardo Teixeira Duarte. Maritime History in Mozambique and East Africa: The Urgent Need for the Proper Study and Preservation of Endangered Underwater Cultural Heritage. J Mari Arch DOI 10.1007/s11457-012-9089-6. http://ml.ci.uc.pt/arquivos_antigos/archport/archport_20_11_2006_a_31_12_2014/pdf56gl1TbbPv.pdf

C.R. Boxer. Four Centuries of Portuguese Expansion, 1415-1825: A Succinct Survey. Witwatersrand University Press. Johannesburg, 1961

J. Mutero Chirenje. Portuguese Priests and Soldiers in Zimbabwe, 1560 – 1572: The interplay between Evangelism and Trade. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1 (1973), pp. 36–48

Hoyini H.K. Bhila. The Manyika and the Portuguese 1575 – 1863. https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/33633/1/11010394.pdf

W.F. Rea. Rhodesiana Volume No 6, 1961. Rhodesia’s First Martyr, Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J

G.M. Theal. Records of South eastern Africa (9 Volumes) published for the Government of the Cape Colony, 1899. Father Monclaro quotes are all from Vol 3, P202-253

R. Gray. Portuguese musketeers on the Zambezi. The Journal of African History Vol 12. No. 4 (1971) PP. 531-533

S. M. Ghazanfar. 12 January 2018. Vasco da Gama ’s Voyages to India: Messianism, Mercantilism, and Sacred Exploits. Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective. Volume 13, No 1 India: Globalization, Inclusion and Sustainability

Nuno Luís de Vila-Santa Braga Campos. Between Mission and Conquest: A Review of Francisco Barreto’s Expedition to Mutapa (1569-1573) Vila-Santa, Portuguese Studies Review 24 (1) (2016) P51-90

Notes

[i] Four Centuries of Portuguese Expansion, 1415-1825: P14

[ii] Vasco da Gama ’s Voyages to India: Messianism, Mercantilism, and Sacred Exploits.

[iii] Monclaro’s report in Volume 3 of G. McCall Theal’s translation of Account of the Journey made by Fathers of the Company of Jesus with Francisco Barreto in the conquest of Monomotapa in the year 1569.

[iv] Sebastian I died in battle aged 24 years on the 4 August 1578 in Morocco although his body was not recovered

[v] Monclaro from G. McCall Theal translation of Account of the Journey made by Fathers of the Company of Jesus with Francisco Barreto in the conquest of Monomotapa in the year 1569.

[vi] Vasco da Gama ’s Voyages to India: Messianism, Mercantilism, and Sacred Exploits.

[vii] Portuguese Priests and Soldiers in Zimbabwe, 1560-1572

[viii] Or Manyika

[ix] Ibid

[x] Portuguese Priests and Soldiers in Zimbabwe, 1560-1572

[xi] Ibid

[xii] College of Goa, 9 August 1560

[xiii] Portuguese Priests and Soldiers in Zimbabwe, 1560-1572

[xiv] Ibid

[xv] Maritime History in Mozambique and East Africa

[xvi] R.T. Durte writes: “At the beginning J Mari Arch 123 of the seventeenth century, in Ethiopia Oriental, Father Joa˜o dos Santos refers to nauetas, pangaios, luzios and almadias as boat types sailing along the Mozambique coast in a traditional local trade network in which Portuguese institutions had been integrated. In his interesting description, dos Santos make valuable references to naval construction, navigation and trade in the region, reporting the use of very effective mat sails and boats of sewn plank technology using coconut fiber ‘‘coir’’ (dos Santos 1608). Like the mtepe, luzios have disappeared from the Zambezi and other rivers and extensive bays in Mozambique and at present no remains have been found of these boat types. However, zambucos and pangaios sailed along the northern Mozambique coast and up to India and Arabia until the twentieth century, following a long established traditional trade network carrying people and goods (Alpers 1975). They are no longer found in Mozambique, but can be seen today in Zanzibar, Mombasa, and other harbors of the Tanzanian and Kenyan coasts. A clearly expressive 1860 image of Mozambique Island harbor by L. McLeod shows that, with the exception of a British steamer, the majority of the crafts moored there at the time were traditional Indian Ocean trading vessels (McLeod 1860) (Fig. 6). In the foreground of this beautiful picture is the image of an ocean-going pangaio that curiously resembles an old Portuguese caravela in its rigging with ‘‘lateen’’ sails. Also illustrating Mozambique Island harbor is a 1814 drawing in H. Salt’s book, A Voyage to Abyssinia…, in which the jetty, customs house and Saint Paul’s (Governor’s) pal

[xvii] Património de Influência Portuguesa (hpip.org)

[xviii] i.e. a tomb or grave

[xix] About 5 miles or 8 kilometres

[xx] Probably malaria and dysentery

[xxi] The English league is 3.45 miles or 5.556 kilometres; the Portuguese légua or legoa is 3.86 miles or 6.174 kilometres

[xxii] Tete is 35 kms above the Mazoe / Zambesi confluence

[xxiii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arquebus/use with other weapons

[xxiv] Portuguese musketeers on the Zambezi

[xxv] Monclaro, “Account of the Journey”

[xxvi] Wikipedia states Barreto is buried at the Igreja de São Lourenço in Lisbon alongside his wife, Brites de Ataíde, so I assume he was re-interred.

[xxvii] Wikipedia refers to 550 men

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: