The Selous Road from Fort Salisbury to Old Mutare and beyond

The Selous Road from Fort Salisbury to Old Mutare and beyond

Selous cut many roads in Matabeleland, Mashonaland and Manicaland. The Royal Geographical Society has the following manuscript maps which Selous’ drew as he surveyed and cut a network of roads suitable for wagons:

(1)A compass survey showing the roads cut during a year’s employment with the British South Africa Company from September 1890 to September 1891 (1:255,000 scale)

(2)A sketch map showing the route from Fort Charter to Mutasa’s kraal and then to Mount Wedza [Hwedza] and then routes to Makoni’s, Mangwendi’s and Maranka’s

(3)A sketch of a route from Old Umtali to M’pandas in Mozambique in 1891 (1:255,000 scale)

(4)Sketch of Mashonaland showing the tribal boundaries (1:255,000 scale)

(5)Survey map of the territory ruled by the Makorikori chiefs[i] for which a mineral concession was granted to the Selous Exploration Syndicate

(6)About 30 sheets of manuscript maps

The region below the Zambezi to the lower Mazoe river had been explored by 1895 by Paiva de Andrade, Captains Capello and Ivens, M. Décle, Montague Kerr, Sir John Willoughby, Carlos Wiese, Livingstone and F.C. Selous, but E.G. Ravenstein who compiled the 1:1,000,000 Map of Mashonaland and Manica wrote none were better than those prepared by Selous.[ii]

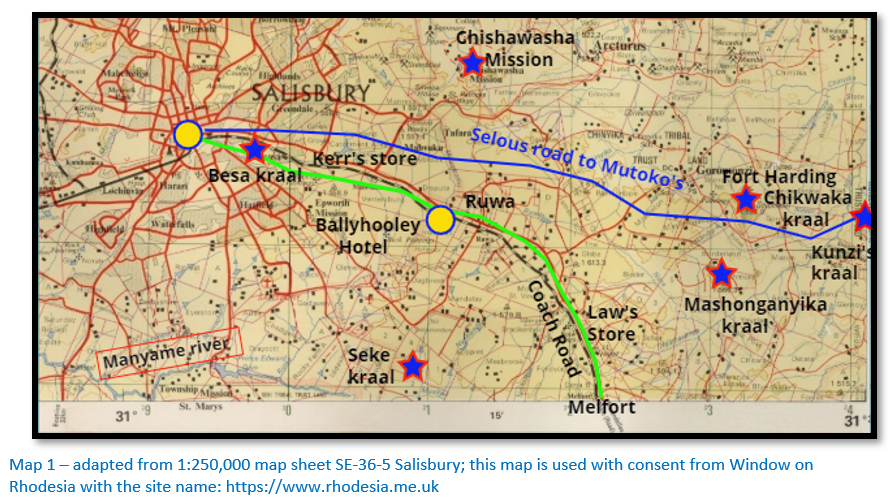

So, although the road from Salisbury to the Odzi river is often referred to as the Selous’ road, he cut many other of the early wagon roads and was chief scout for the Pioneer Column as well. This article takes up from 1 October 1890; the date the Pioneer Column was officially disbanded at Salisbury.

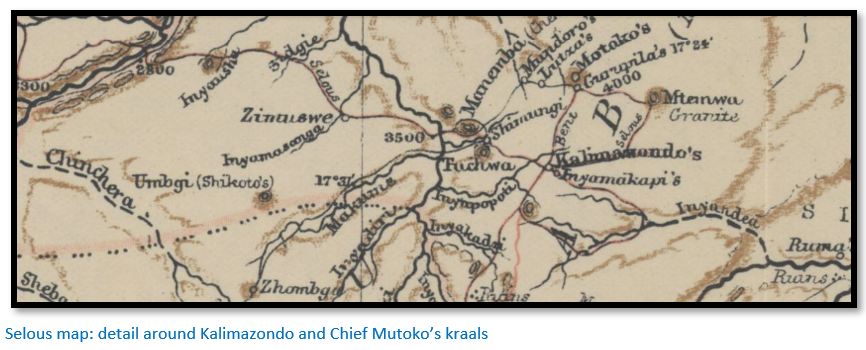

Selous signs a mineral concession with Chief Mutoko

In his book Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa, Frederick Courteney Selous writes that he left Fort Salisbury on 19 December 1890 with W. Leslie Armstrong, [See biographical details below] also an employee of the British South Africa Company (BSACo) to conclude a mineral concession treaty with Chief Motoko [Mutoko] They took a wagon on the track to Chief Mangwendi’s kraal before branching off in a more easterly direction towards Sikadoro’s town. The paths they followed took them through a succession of shallow valleys, each with its clear stream of running water. He names the rivers as the Nola, Inyagui, [Nyagui] Inyakambiri, [Nyakambiri] Shabanoghwi, [Shavanhohwe] Ungurughwi and the Monyokwi as well as innumerable smaller streams before reaching Rusunsgwe hill, [near the Bokota Mountains] about 50 kms (30 miles) from Mutoko’s kraal on 26 December.

After passing Rusunsgwe hill they spent much energy chopping a path for their wagon through groves of mahobohobo trees (Uapaca kirkiana or Muzhanje in Shona) on the 27 December crossing the Inyamashupa river [Inyamshupa] which Selous says forms the boundary between the Mangwendi / Mutoko territories and the following day reached Kalimazondo’s kraal about 10 kms (6 miles) to the south-west of Mutoko’s.[iii] Here they waited four days whilst the old chief communicated with the spirit-medium “Mhondoro” or “Lion-God” who Selous states is the only god the Mashona people north and south of the Mazowe river know of, or worship, and no step of any importance is ever taken until the spirit-medium has been consulted.

Selous describes the people in the Mutoko region as the Mabudja [Buja] and says that in 1890 unlike many other tribes which had been scattered in the 1820-1840 Mfecane, the Buja people were still a unified and warlike nation, capable of putting thousands of warriors into the field and with a strong belief in themselves and in their god.[iv] At the time he writes, the Buja were particularly proud as they had beaten off an attack by a well-armed force of Manuel Antonio de Souza, [Gouveia] the Capitao Mor [military captain] of Gorongoza.[v]

At length after waiting four days in very wet weather a message came, telling Kalimazondo to take the white man by the hand and bring him to Mutoko the following day. They reached the vicinity of Mutoko’s kraal on 2 January 1891 but were only given an interview with the old chief on 6 January. Selous had explained the purpose of his mission, which was for a mineral concession with the BSACo, to the elders of the tribe in the interim period. The elders said they were happy to make friends with the British and would allow them to search for gold and make roads, but they seemed suspicious about their chief signing any papers.

Selous says they were visited by hundreds of local people, all of whom were good-natured and curious about the white men, the wagon, the oxen [much bigger than their small breed of cattle] the horses and donkeys. On the 6 January accompanied by Armstrong and William Hokogazi, his Zulu servant, and Sipiro, his interpreter, they walked through a great crowd of local people squatting on a flat granite rock and an estimated thousand plus warriors, all fully armed.

Chief Mutoko sat at the highest point of the granite rock in the shade of a shelter of branches which had been erected over him, behind were two mbira players and senior elders were on either side of him. As soon as they were seated praise singers shouted out the chief’s honorary titles along with a women’s chorus. Selous explained the purpose of his mission and why it was necessary for the chief to sign his agreement in writing on the paper.

In reply Chief Mutoko referred to the Portuguese attack on himself, he had heard that the Portuguese were defeated in Manicaland by the BSACo [See the article How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] and finally that he was glad to conclude a treaty of friendship with the British and that they might go where they liked to look for gold. He then made his X on the document, his sons Siteo and Kalimazondo signed as his witnesses and Armstrong and Hokogazi witnessed for the BSACo.

Selous says Mutoko’s country included a very large area east of Mangwendi’s territory between the Ruenya and Mazowe rivers and also the Kaiser Wilhelm goldfields visited by Mauch [See the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] The Buja people were very different in appearance, manners and culture to all the other tribes of Mashonaland, their people are well-supplied with vegetables and the best rice, physically they were well-built and courageous in spirit…Selous thought that Chief Mutoko had a force of five thousand fighting men.

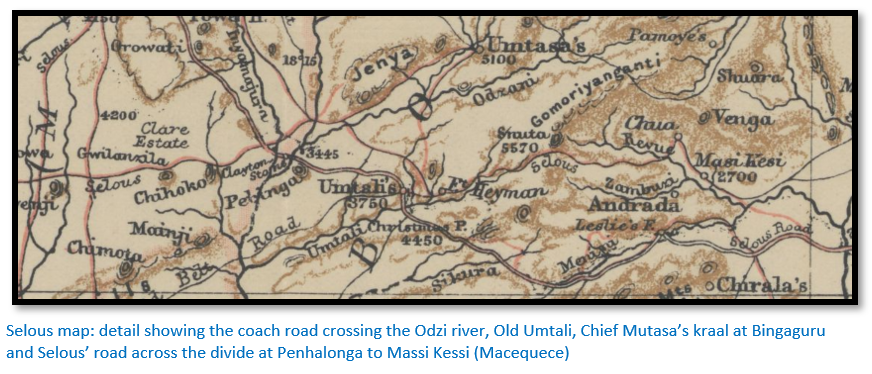

Selous makes a wagon road to Umtali

Having finished his business with the Chief Mutoko, Selous trekked through the territories of Chiefs Mangwendi and Makoni with his wagon and companions to Umtali. [This was at the site of Fort Hill, labelled Fort Heyman in his map…see the article Fort Hill – the first site of Umtali (now Mutare) under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] The decision to move to the second site at Old Umtali – now the Methodist mission - was only made in December 1891]

At the time there was some debate as to whether the best route to the Indian Ocean would be via the Pungwe or Buzi rivers. Selous had received orders to assist Lieut. Bruce [See biographical details below] of the BSACo Police in cutting a road to Umliwan’s kraal on the Revue river.

A new road from the Odzi river to Salisbury

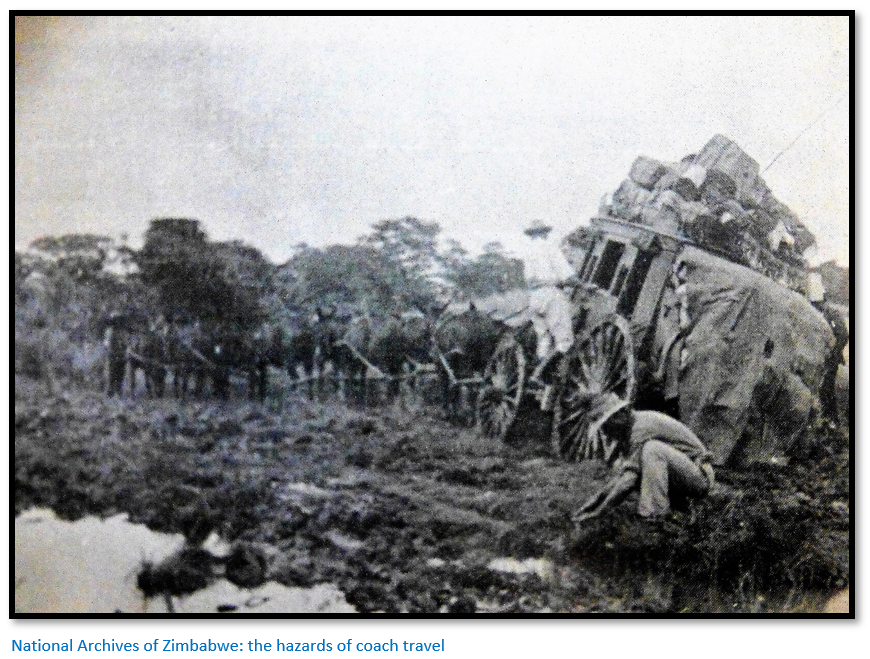

Selous had also been asked to construct an entirely new road from the Odzi river to Salisbury as the old road via Mangwendi and Makoni’s kraals had proved impassable during the rainy season of 1890 – 91. Maurice Heany was a partner in Messrs Johnson, Heany and Borrow and generally directed the road-building operations. [See short biographical details below] A.S. Hickman writes when Captain A.G. Leonard, in command of E Troop of the BSACo Police, was paid off he set out on foot with Herbert Molyneux for Beira from Salisbury with a scotch cart to carry their baggage. They reached Old Umtali after a journey of ten days and then onto Macequece and Sarmento. On the way they passed about twenty wagons and two new coaches abandoned in the tsetse-fly area and rotting in the sun and heavy rain. These were some of the remains of Messrs Johnson, Heany and Borrow’s attempt to establish a transport route to the East Coast on which they are said to have lost £25,000.[vi]

Elsa Goodwin Green corroborates this saying that above the Devil’s Pass they replaced a broken wheel on their wagon with one taken from an abandoned wagon left on the highveld. [See the article The story of a nurse and authoress travelling on the Selous Road through Mashonaland in 1896 during the Mashona Rebellion of First Chimurenga under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The Odzi river was in flood in mid-February 1891 and Selous and his party were forced to camp on the riverbank for fourteen days although during that time he managed to swim across the river twice with his shooting pony and visit Captain Heyman’s camp at Fort Hill. However, when the floods down the Odzi at the end of two weeks showed no signs of abating Selous decided they should begin the work of cutting the new road. His only European companion was W.L. Armstrong[vii] who had accompanied him to Mutoko’s who he describes as a cheerful, willing and intelligent lieutenant.

Selous says that although they were out in a wagon during the whole of this very severe rainy season, often working day after day on the road, barefooted in the mud and water or in the full heat of the sun laying corduroys[viii] across the bogs, neither of them had a headache, let alone a fever. Selous may have been acclimatized, but Armstrong had only come out from Harrogate the year before…Selous attributed their good health to keeping their minds and bodies constantly occupied.

W.L. Armstrong succeeded by Sergeant (later Major) John Charles Jesser-Coope

Armstrong was succeeded by Jesser-Coope. Selous writes that both Armstrong and Jesser-Coope were excellent young fellows, and he was very fortunate to have them assigned to assist him in the road work. He describes them as good-tempered and patient with the labourers and not afraid to soil their hands by handling an axe or spade; always ready to set an example by hard work, conscientious and never grumbling.

Completion of the new road from the Odzi river to Salisbury

On 3 May 1891 Salisbury was reached after they had laid out 240 kms (150 miles) of new or improved road through very difficult terrain which included much boggy ground from the innumerable streams which flow off the watershed of Manicaland and Mashonaland. Selous says he needed three strong horses to cope with the amount of riding this work entailed in scouting out the best routes for the new road. Sometimes he would get a good potential line for 20 kms (12 miles) before ending amongst bogs that would take endless time and labour to corduroy, so he would have to give up and try to find another route.

In one place he was six days, riding over 64 kms (40 miles) per day before he found a route to his satisfaction. He never moved the wagon until he had a good line for at least the next 32 kms (20 miles) on ahead. His object was to select a line as direct as possible that crossed a minimum of boggy ground and could then be made into a permanent road at the least possible expense to the BSACo.

Trouble with the Portuguese in Manicaland

When he reached Salisbury the survey, but not the corduroying of the road had been completed and it was Selous intention to get a fresh supply of trading goods to pay the native labourers and then return and complete the road. However just before Selous’ arrival at Salisbury, the first Administrator of Mashonaland, A.R. Colquhoun, heard that a Portuguese military expedition was making its way up from the coast with the aim of driving the BSACo out of Fort Hill.

Civilian prospectors were unofficially encouraged to move into Manicaland – Maurice Heany persuaded “Sandy” Tulloch, who later owned the Liverpool Mine with three months rations and ten extra gold claims, to trek from Hartley Hills to Manicaland and Sgt-Major Lyons-Montgomery[ix] and four police troopers from B Troop left Salisbury for Mutasa’s kraal. [There are photographs of the Liverpool Mine in the article Penhalonga under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Colquhoun asked Selous to take a contingent of BSACo Police and two wagon loads of supplies and ammunition to assist the small force garrisoned at Fort Hill. So, with twenty BSACo police and some ex-pioneers including Lieutenant Adair Campbell [See biographical details below] they set off for Manicaland on 5 May 1891. Nobody thought much would happen before the 15 May, which was the date on which the modus vivendi between Britain and Portugal expired. [For further details of the modus vivendi see the article The Pink Map: how credible were Portuguese claims to Mashonaland and Manicaland before 1890? under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Before the party reached the Odzi river moving slowly with the two heavily-laden wagons, Henry Borrow overtook them on his way to assist Captain H.M. Heyman and the BSACo Police at Fort Hill in resisting any Portuguese incursion across the Divide. So, they were bitterly disappointed when they reached Fort Hill on 13 May 1891 to hear that on the 11 May, four days before the expiration of the modus vivendi the Portuguese had made a sortie from Massi Kessi [Macequece] and attacked Captain Heyman’s camp in the Chua Hills.

Battle of Chua Hills

Selous’ description of the battle is light-hearted. He says the Portuguese were unaware that Heyman’s forces had a seven-pounder gun.[x] Captain Heyman and his men were in a good position and he handled his men with good judgement and coolness. The Portuguese were mostly composed of Angolan African levies who grew fearful as the canister shot fell amongst them and shot badly with none of Heyman’s men being hit.

He writes: “When they found that they were getting within range of the canister shot which began to drop amongst them, it may well be understood that these black levies, who did not care one brass farthing whether the British or the Portuguese flag waved over the hills of Manica , felt more inclined to retreat than to advance and soon, in spite of the utmost efforts of the two Portuguese officers who are leading them, they bolted back to Massi Kessi [Macequece] followed by the Portuguese.”[x

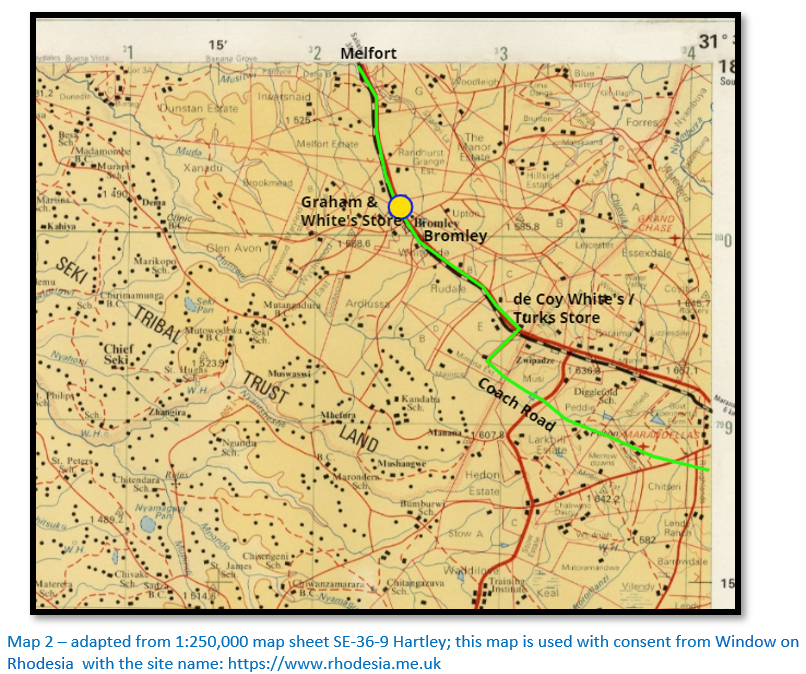

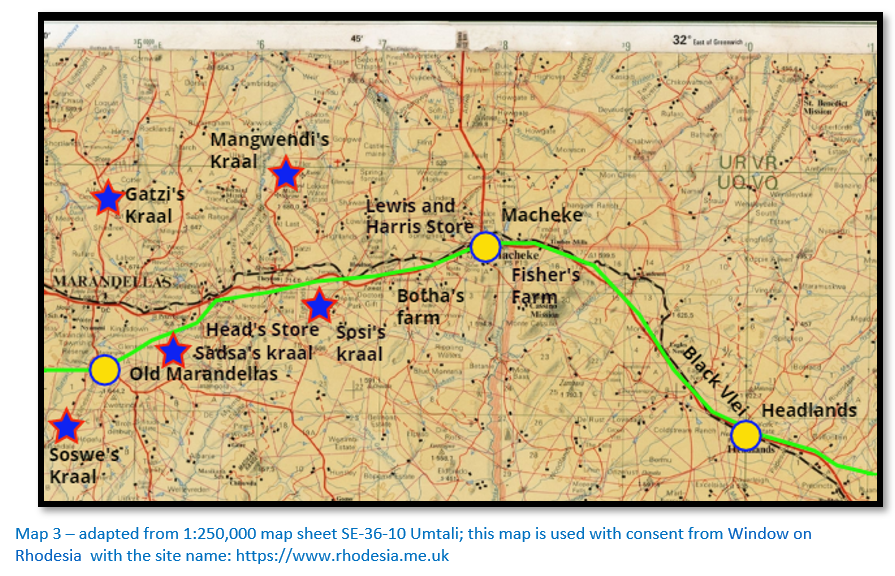

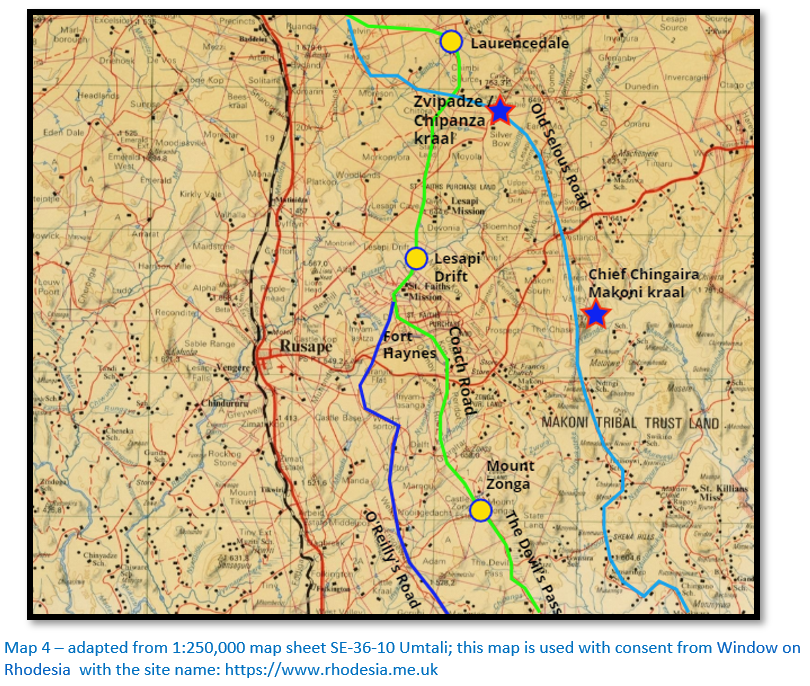

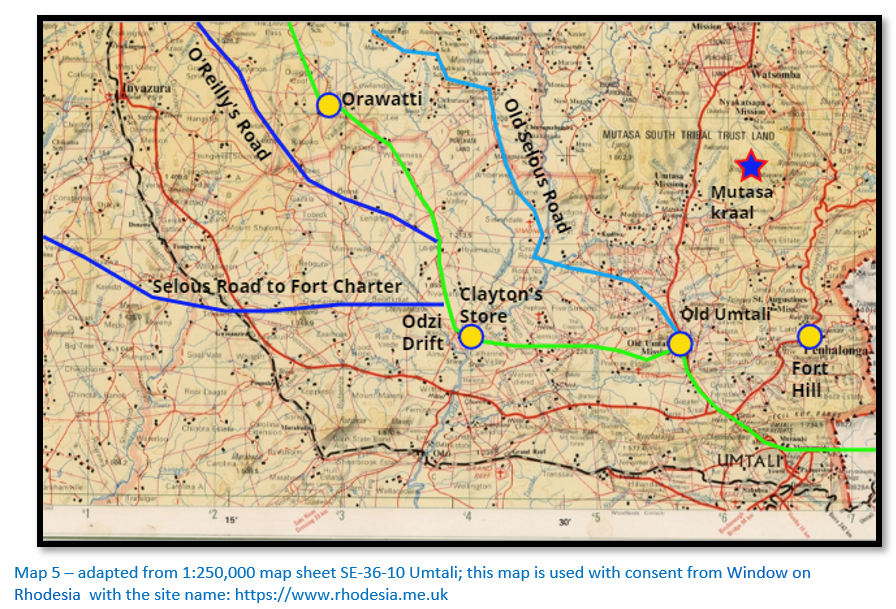

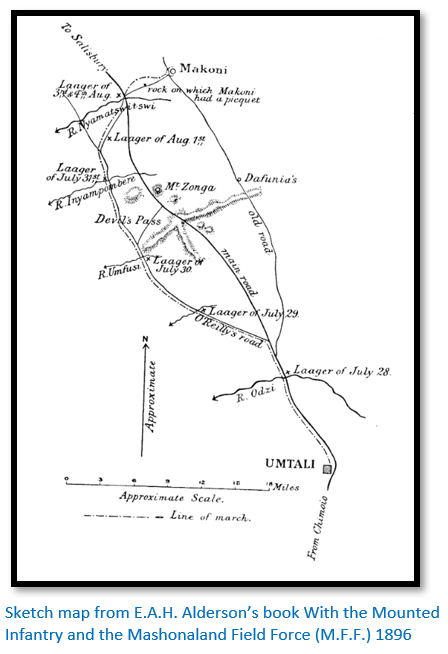

The green line indicates the Selous road used by the Zeederberg coaches. The yellow-blue circles are the coach stops where the mule teams were changes and passengers might be able to snatch a quick meal or drink.

The above sketch by Lt-Col A.E.H. Alderson from the Odzi river to Chief Makoni’s kraal shows the three wagon roads that had been cut by July 1896. The original “old road” cut by Selous went from kraal to kraal: Chiefs Chikwakwa, Kunzi, Mangwendi, Chipanza, Makoni and referred to as the “old road” above.

Then Selous cut the coach road from the Odzi river to Salisbury with Armstrong from February to May 1891 that is labelled “main road” above.

In 1892 Jesser-Coope was made Inspector of Roads in the Manica district and cut what was known as the “O’Reilly’s Road” between Lesapi drift and the Odzi river. This route was used by Lt-Col. Alderson and the Imperial Forces in 1896 during the Mashona Uprising or First Chimurenga to by-pass the Devil’s Pass when they marched from Umtali to attack Chief Chingaira Makoni’s stronghold at Gwindingwi Mountain.

The Coach Road from Old Umtali to Salisbury

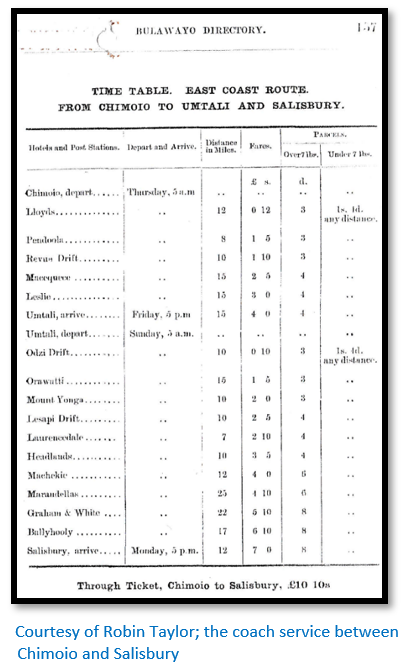

Robin Taylor writes that the coach operators provided the passenger and mail service before the railways were constructed. On 12th August 1893 Bezuidenhout and Symington advertised in the Herald a smart passenger and mail service between Salisbury and Umtali starting on 14th August. The first coach would leave Salisbury at 4pm that day. They claimed if mules were used it would be a two-day journey to the rail terminus. This would appear to be overly optimistic as oxen hauled the coaches at that time between Umtali and Chimoio.[xii]

In October 1892 the coach service from Pretoria to Fort Tuli (6 days) was run by Zeederberg and Hollins and from Tuli to Salisbury by H. Bezuidenhout’s mail coaches (12 days) However by April 1893 Bezuidenhout only had the Victoria to Salisbury section until the 1 August. From that date he would only have the Salisbury – Umtali coach service and thus Zeederberg’s came to dominate the coach services.

There are many descriptions of travel by coach, but few of travelling on the Umtali to Salisbury route. This description by James Alfred Cope-Christie, who was the architect of many of the more important buildings in Salisbury, now Harare and came to the country in May 1894 after submitting and winning an architectural competition for a Stock Exchange building.[xiii]

“The first portion of our trip was from Beira to Fontesvilla, or Ponte-do-Pungwe as it is now called. This we did in a small paddle steamer. I remember when starting, that Jeffreys[xiv] made a bet of a fiver with the captain of the boat - Dickie, by name - that he would run the boat on the sands during the trip up the river. We did not get stuck and when Jeffreys paid out smilingly, he said it was a cheap fiver’s worth. Dickie usually got stuck if he wanted to sell the drink he had on the boat.[xv]

From Fontesvilla to Chimoio was the next portion of the journey, which we did on the narrow-gauge railway. We had not gone more than a few miles when in the long grass at the side of the line we spotted a lion and three lionesses. We stopped the train, but the lions cleared off in the long grass. I wondered what country I was coming to. At Chimoio, the railhead, thanks to Jeffreys I obtained the loan of a horse which had been ridden down by George Pauling, the railway contractor. His wife and others had journeyed in a Cape cart in which Mr and Mrs Jeffreys returned in to Umtali. As I had never been on a horse before in my life one can imagine my feelings when I got off, or fell off, at the end of the first day's journey. Anyhow, I felt it better to ride then to walk, for that is what it meant.

Just before arriving at Old Umtali and going over Christmas Pass, Jeffreys pointed out the site of the proposed new Umtali township. I little thought that shortly after I should be visiting the spot with Cecil Rhodes, Colonel Beal and Captain Scott-Turner to choose the sites for the cemetery, park, brickfields, native location etc. At Old Umtali I said goodbye to the Jeffreys and proceeded to Fort Salisbury by a Zeederberg coach and arrived there on 19 May 1896.”

Clearly the journey was not as uncomfortable as riding a horse!

BSACo Police under Lieut Bruce cut a road to Umliwan’s kraal in Mozambique

Selous was then ordered to Umliwan’s to fetch two wagons and some of the BSACo Police that had been left in charge of them.

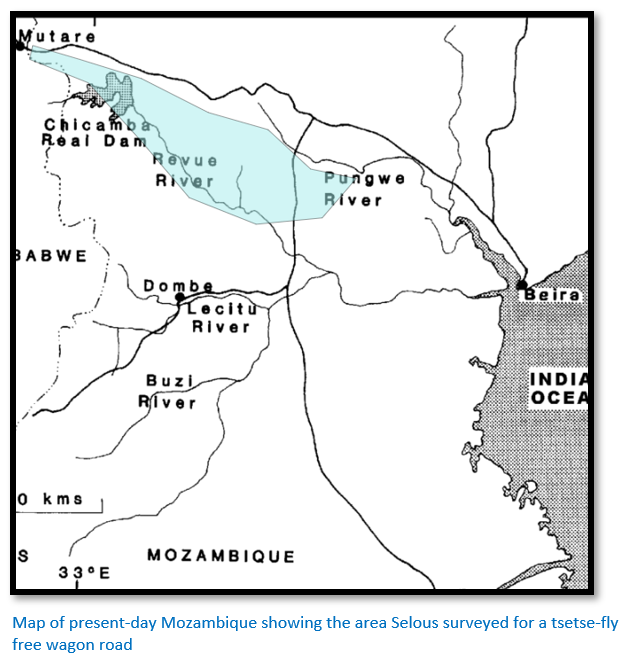

Selous explains that Umliwan was an independent chief living between the Pungwe and Buzi rivers, who nevertheless paid tribute to Gungunhana, the Gaza chief. Selous maintained that he denied the four hundred year old sovereignty claim put forward by the Portuguese, but probably this is because the Portuguese claim was also denied by the BSACo, which Selous supported.

The BSACo had concluded a treaty with Umliwan at the end of 1890. Umliwan’s territory lay within 100 kms (60 miles) of the confluence of the Revué and the Buzi rivers and the Buzi was said to be navigable at that point to shallow boats. Lieutenant Bruce had been sent to cut a wagon road from Manica to Umliwan’s kraal and to form a Police post there. This had been done during the worst months of the rainy season and the men had suffered badly from fever, bad food and exposure. Many of their oxen had fallen into game pits or were so exhausted by the trekking that they died.

When news came of the Portuguese advance on Fort Hill, lieutenant Bruce and his men were recalled to reinforce the little garrison at Fort Hill, and he had to abandon the wagons and leave Sergeant Stanley and four Police who had been down on the Buzi river.

Selous sent to Umliwan’s kraal

Selous was despatched to collect the wagons and the five men from Umliwan’s. He took with him besides his own wagon and oxen, two spare spans and trek gear with two drivers and was once again accompanied by W. Leslie Armstrong.

Three days after leaving Fort Hill they met Sergeant Stanley and his men between the Mineni [Munene] and Uzonway rivers, all of them well, but suffering from fever. They all travelled to Umbayo’s kraal, before Selous and the spare drivers and oxen spans went onto Umliwan’s which was reached on 31 May 1891.

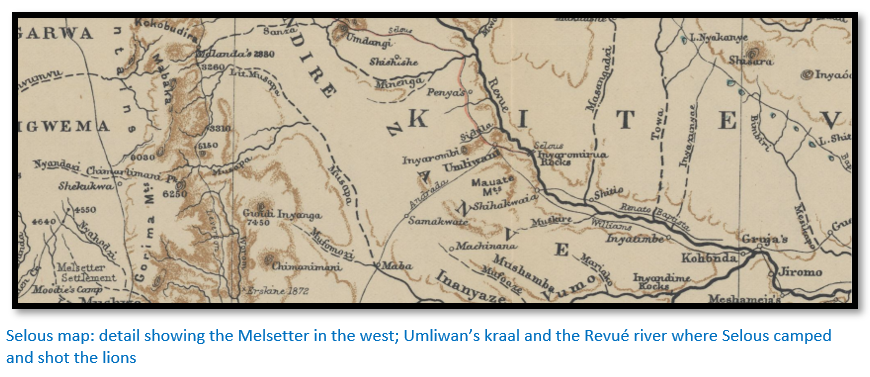

Whilst the drivers were getting the wagons ready, Selous went down to the Revué river with Umliwan’s men to look for hippo. As Umliwan assured him there was no tsetse-fly, he took his three horses with him to bring back as much meat as possible. The pools they were guided to on the river 13 kms (8 miles) to the south-east [probably now under Chicamba dam] were empty of hippo, but as they walked along a hippo path: “and to my horror saw that my two priceless shooting horses were covered with tsetse-flies, or at any rate, that there were at least twenty on them.” The flies were chased away or killed, and the hippo hunt abandoned. “When I showed the flies to Umliwan, the old brute said in a most unconcerned way, ‘Yes, they are the impugan…[tsetse-fly] they must have come from the buffaloes beyond the Revué.”[xvi]

Visited by lion

By 8 June 1891 the empty wagons had still not come from Umliwan’s and Selous and Armstrong were camped some way back on the trail to Manicaland. They were rather bored as it was impossible to hunt with the thick bush and long grass. Before turning in, they looked around the camp, it was a new moon, the oxen were lying around the wagon surrounding the horses which were tied to the wagon. Armstrong was in the afterpart of the wagon; Selous in the front. At first their servants smoked dagga [cannabis] around the fire and were noisy and talkative, but finally everything became quiet.

At 4am they were awakened by the oxen stampeding and both Armstrong and Selous jumped from the wagon. The horses were still lying down, but none of the oxen were to be seen. The servants were throwing fire-sticks and shouting “shumba, shumba” [Lions, lions] His Zulu driver fired two shots, although Selous doubted if he had seen anything, the night was so dark. Then the oxen stampeded once more crashing through the underwood on the right of the wagon and they heard an ox’s agonised bellowing’s as a lion got hold of it.

The driver and Selous ran towards the sounds their torches of blazing grass lighting up the bush and the lions growled and were frightened away, although none were seen in the circle of light. The ox ran towards a small stream below the camp, but: “He was soon caught again, and bellowed terribly, poor brute, but the lions did their butcher’s work without uttering a growl; they were several minutes killing him.”

There was nothing for it, but to make up the fires, put double reims on the horses and wait for dawn. “The lions were singularly quiet, although every now and again we could hear them crunching the bones of their victim…. The red dawn now began to give place to a dull grey light and at last I was able to see the ivory sight of my rifle.” Armstrong, Selous and their Zulu driver with their big dog Tiger advanced slowly and cautiously down the wagon track towards the drift where they could hear what Selous thought were lions crunching bones. But they saw that there were two hyenas on the ox carcass, which soon beat a hasty retreat.

Once they crossed the stream Selous established that the lions had eaten until daylight and then left, giving the hyenas a chance to get a snack before sunrise. However, as they walked around the carcass, they heard loud growls and the dogs were cowed and frightened. When they got back to the wagon their native servants said they had seen four lions break cover and cross a piece of open burnt ground. Selous saddled his horse and rode after them, but the bush was too thick away from the footpath and he soon gave it up. The remaining oxen were found five hundred yards away feeding quietly as if nothing had happened.

Hunting down the lions

From the spoor there appeared to be four lionesses and a male lion. What to do next as a pack of lions represented a big threat to the oxen and horses. The grass was too thick to follow them and as Selous only had three rifles he could not set gun traps. He decided the only solution would be to sit up for them, but as the trees near the carcass were not big enough for a platform, they would have to build a shelter on the ground.

Three stout poles in the shape of a tripod formed a hut structure, the spaces in-between were filled with stout saplings and finally camouflaged with branches leaving a small entrance…the hut about nine and a half paces from the ox carcass. Selous thought that no matter how dark it was at this distance he would see the lions, but he did not realise how dark the surrounding bush made the scene and a thick mist rose nightly from the stream.

At 6pm having finished dinner, Armstrong and Selous took their blankets and rifles and crawled into their hut closing the gap behind them with poles left for the purpose. Within an hour they heard stealthy footsteps on the large dry mahobohobo leaves lying around which became noiseless once they reached the wagon track. In the pitch black darkness Selous could not tell if the intruder was lion or hyena and determined not to fire until he knew. A shadowy form stood by the carcass and then moved within yards of the hut looking at it suspiciously…its boldness made Selous think it must be a lion. Then two more vague and misty forms came out of the darkness and as one advanced towards the hut he thought from its size it must be a lion.

After whispering to Armstrong “I’m going to fire” he watched the dark shape come within three yards and then pulled the trigger. The rifle report was almost instantly drowned by the terrific roaring grunts of a wounded lion which rolled or just fell down the steep bank of the stream and lay moaning at the bottom, mere yards from them. Soon a gurgling noise told him the animal was at the point of death.

Selous had scarcely reloaded his rifle when a second shape appeared from the darkness. He thought it might be a hyena, but as it was now very close, fired at it and instantly heard the hoarse grunting roars which signalled it was a lioness. This too, either rushed or fell down the steep bank of the stream and they could hear her evidently dying, the first furious grunts being succeeded by low moans, until there was silence, and he knew both lay dead.

Only a minute had passed, and he had just whispered to Armstrong that things were probably over for the night when they heard an animal breathing alongside the shelter and giving it a gentle shake as it looked for an entrance and tried to get a paw through the poles. As the poles were not fixed to the ground the lion might have got its head and shoulders through and overturned the whole structure, so Selous turned over and pushed the muzzle of the gun through the poles and pulled the trigger.

Once more, for the third time the rifle report was answered by the most terrific grunting roars within six feet of where they lay. Selous writes: “Well, the expanding Metford[xvii] received at such close quarters, must have given the lion a nasty jar.” It fell over and Armstrong fired through another opening at the sound of the roars. The wounded animal, still grunting loudly, made a rush through the bushes behind the hut and then fell from the bank of the stream with a loud splash into a shallow pool of water. Here it lay for some time splashing the water slightly and moaning. Selous says: “we thought we had got three lions in about five minutes and felt very pleased with ourselves.”

They now spread their blankets and lay down to sleep, but before midnight heard an animal sniffing around the back of the hut, which Selous put down to a hyena. An examination next morning showed no hyena spoor, only that of lions!

The last wounded lion’s groans came at longer and longer intervals but served to keep them awake. Between midnight and 2am they heard animals feeding at the carcass and one of them snarled at its companion confirming they were the two remaining lions. Although they were less than ten yards away, the night was so dark they could see absolutely nothing. “And now for hours the lions lay, ‘so near and yet so far’ tearing at the meaty portions of the carcass and crunching up the breast bones and the ends of the ribs. Every now and then they would rest from feeding and then lay breathing with a loud blowing noise, then the tearing and crunching would recommence. Every now and then the big lion, as I guessed, would awaken the echoes of the night with a loud grunting snarl, to which the dogs at the wagon always replied with angry barking.”[xviii]

Selous remarks that to be within ten yards of a couple of lions feeding noisily and sometimes snarling loudly would be a sufficiently novel experience to keep one awake; yet he says he had twice to wake up his young companion [A.L. Armstrong] and tell him not to snore as the noise might disturb the lions!

As dawn approached the hyenas began to howl around, apparently answering one another and about an hour before daybreak the two remaining lions dragged the remains of the carcass into the bush beyond the wagon track before suddenly leaving it. In all that time there was not enough light to make out the lions.

Daybreak revealed that the whole valley was enveloped in a dense mist and now the hyenas which had kept their distance whilst the lions fed on the carcass approached gingerly. Four of them came down the wagon road holding their heads high and craning their necks from side to side. Then with a series of wild howls they swerved off to the spot where the lions had left little more than the head and a few bones of the ox and were soon tearing away at what remained. Selous hoped the lions would return and drive the hyenas off their kill, but after half an hour he knew that would not happen and they were just on the point of leaving their hut when a fifth hyena came walking down the road. By now he could see the front sight of his rifle and planted an expanding bullet in the centre of its chest.

The carcasses of the first two lions lay in the stream bed below them; the first a full-grown lioness, the second not as full grown – both had been impacted through the shoulder with the expanding bullet going right through their bodies. The last lioness had lain in the same stream bed for most of the night but had dragged herself into the thick bush and the dogs would not follow the spoor.

Selous says that when Lieutenant Bruce had come through two months earlier, one of their natives from the Orange Free State had been dragged out from under one of the wagons at the same spot and carried off and devoured in the bush. The lions had made another attempt the next night, but fortunately without success.

Further road-building

On returning to Fort Hill Selous set about completing the road between there and Salisbury and by July 1891 the entire road was in good order for heavy wagons with all the boggy sections having been corduroyed and the streams bridged.

Next the BSACo sent him to find a route along the watershed between the Pungwe and Buzi rivers which was free of tsetse-fly. However, this was not possible as he found the whole area as far as M’pandas, not far from Fontesvilla, infested by tsetse-fly. By September 1891 he was back in Salisbury.

His next task was to trek down south to Fort Tuli to check all the wagons he met on the road to establish whether there was enough food coming up to Salisbury before the rainy season made the rivers impassable to wagon traffic. The previous rainy season of 1890-91 had resulted in serious food shortages. He rode down alone on horseback and established that there would be enough food before returning to Salisbury.

On his way back to Salisbury he met Rhodes, de Waal and Jameson at Fort Charter. They asked him to accompany them to Victoria and then to meet Chief Chibi at his kraal. After this he returned with Jameson to Salisbury.

For the next eight months Selous was employed by the BSACo in road making until May 1892 when the road building being accomplished Selous resigned and went shooting and collecting natural history specimens; shooting his last lion, a fine large male on 3 October and his last elephant, an old bull with tusks weighing 49 kgs (108 lbs) on 7 October before making his way down to Beira which he left on 19 October 1892.

Notes on some of Selous travelling companions

William Leslie Armstrong[xix]

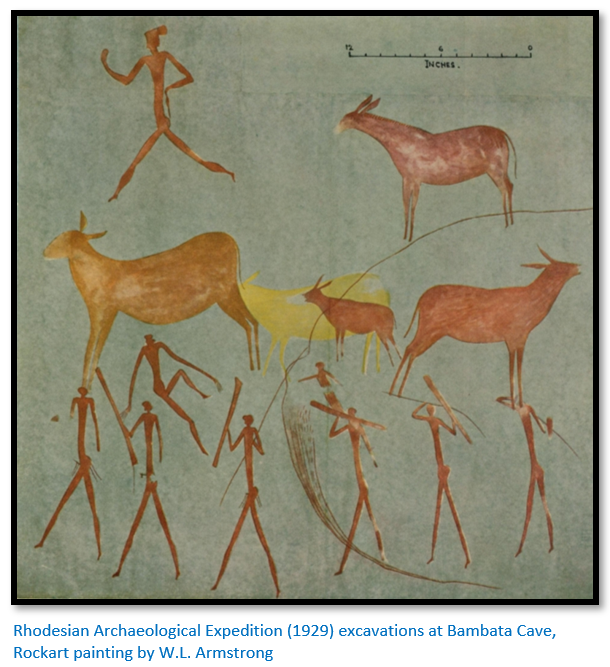

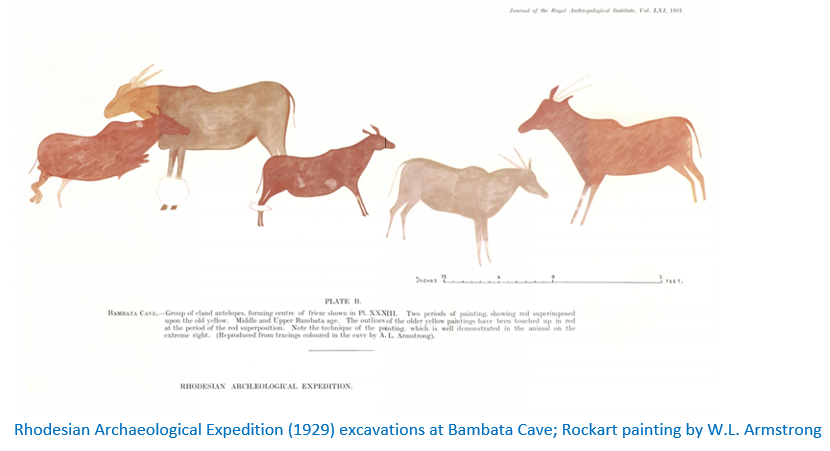

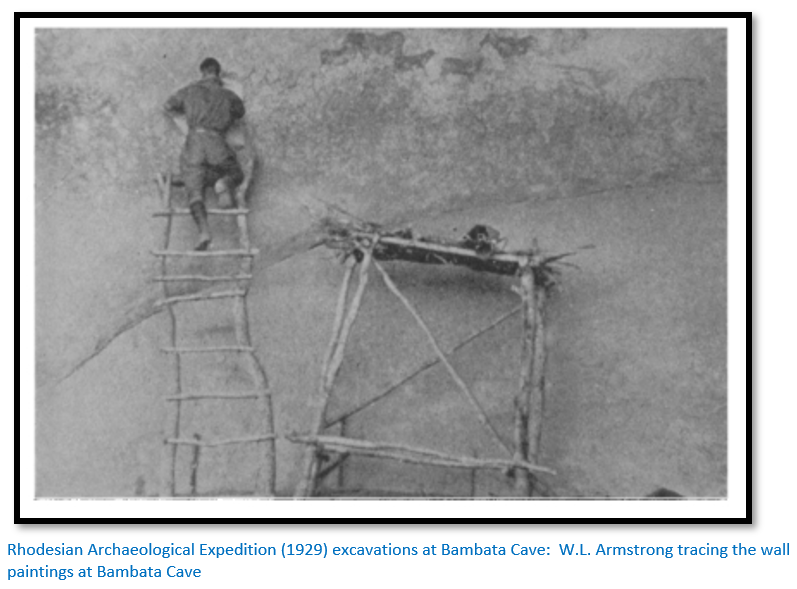

Possibly a relative of Bonar Armstrong who went on a mission with Frederick Burnham to the Mlimo’s Njelele Cave in the Matobo during the Matabele Uprising or Umvukela. W.L. Armstrong also made tracings of the rockart in a paper of the Rhodesian Archaeological Expedition (1929): Excavations in Bambata Cave and Research on Prehistoric Sites in Southern Rhodesia by A. Leslie Armstrong in The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Vol. 61 (Jan. - June 1931) where the author refers to W.L. Armstrong as his son.

Robert Cary calls him Owen Richard Armstrong, as Trooper No 160 in the Pioneer Column, but as he worked with Selous on road cutting in 1891, I assume he is the same person and first names have become confused.

He attested as a trooper in the BSACo Police on 1 July 1890 and was discharged from C Troop on 28 September 1891 as the BSACo tried to stem its outflow of cash. He was fluent in Zulu – a rare skill at the time.

During this period with the BSACo Police Armstrong accompanied Selous to sign a mineral concession with Chief Mutoko and then accompanied him in constructing the Selous Road from Salisbury to the Odzi river and then to Umliwan’s kraal.

In the 1893 Matabele War he rode with Johan Colenbrander and Mullins from Palapye in Bechuanaland, now Botswana to Bulawayo with dispatches for Dr Jameson with news of the Southern Column under Col. H. Goold-Adams arriving on 7 December 1893.

He accompanied Major P.W. Forbes in the pursuit of Lobengula and their retreat back down the Shangani river. He also accompanied Frank Burnham down the Bubye river and reported they had seen large numbers of amaNdebele and cattle (Burnham estimated 7,000) travelling east

At the first anniversary celebrations in the Charter Hotel, Bulawayo in November 1894 Armstrong entertained the diners: “rendering one of the droning Matabele chants in fine style.”

Perhaps because of his 1891 journey with Selous and his good language skills he was appointed Native Commissioner at Mutoko’s in the Abercorn District just prior to the Mashona Uprising or First Chimurenga in June 1896. He was on leave at the time of the killings, but H.H. Ruping who was acting for him, was killed by his native police at Mrewa’s [Murehwa] kraal about 24 June 1896.

In early March 1897 he went as guide to Sub-Inspector Colin Harding and twenty BSACo Police on a patrol to the Mutoko area to raise a levy of Buja friendlies. They set off from Fort Harding near Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal [See the article Fort Harding, Chief Chikwakwa and Headman Gondo’s kraals and Warrendale Farm police Camp under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] and returned accompanied by Gurupila (Chief Mutoko) and five hundred of his men. On 15 March they were attacked in a rocky pass by the Boruzwi tribe between the Inyagui and Nyadire rivers – the levies deserted, but the pass was cleared.

Reinforcements were requested and when Lieut-Col de Moleyns met up with them near the Inyagui river with twenty-five BSACo Police he found the whole force down with fever except for Harding, Armstrong and three men. On 30 March 1897 with additional reinforcements, they attacked a rebellious Mashona force at Domborembudzi Mountain (the mountain of goats) and drove them off, although two of Gurupila’s sons were wounded.

The sick police were sent back to Salisbury and de Moleyns continued with Armstrong and the force to Shaungwe (Zhombwe Mountain) Here another skirmish broke out as they captured the hill during which Gurupila was mortally wounded. His death created superstitious fears amongst his tribesman who then threatened to kill the BSACo Police who were forced to beat a hasty retreat to Umtali.

Armstrong resigned his Native Commissioner post and died of blackwater fever at Salisbury Hospital on 30 November 1900. See his Obituary below.

William Leslie Armstrong’s Obituary in the Leeds Mercury, Monday 31st December 1900

The following was kindly sent to the website by Berenice Baynham

News reached Harrogate on Saturday afternoon of the death from blackwater fever of Mr W. Leslie Armstrong, eldest son of Mr. and Mrs. J.L. Armstrong, of Blairgowrie, Harrogate. Mr. W. L. Armstrong, whose death took place on November 30th, at the hospital, Salisbury, Mashonaland, South Africa, had a most successful career in South Africa. In 1890 he went up with the pioneers who took possession of Mashonaland for the British South Africa Company. He attracted the attention of Dr Jameson and Mr Rhodes and was soon enrolled in the Civil Service. He travelled several times beyond the Zambesi, and was successful with the natives, being, as Mr F.C. Selous stated of him, "good-tempered and forbearing with them." For three years he was associated with Mr Selous and accompanied this famous traveller on many political missions to the native tribes and in engineering work for the Chartered Company. The strange adventures of Mr Selous and Mr Armstrong - when for three years they never slept in a bed - are narrated at some length in Mr Selous's Travels and Adventures in South-east Africa. Subsequently, though quite a young man, Mr Armstrong was appointed a Native Commissioner, and afterwards a Justice of the Peace for Mtoko, some 130 miles north of Salisbury. During Mr Armstrong's absence on furlough some two or three years ago his deputy [Mr H.H. Ruping] was murdered. Mr. Armstrong was also for a short time Native Commissioner and J.P. for one of the Mazoe districts. He took an active part in suppressing the native rebellion in Mashonaland, and was awarded a handsome special grant, together with the medal for conspicuous services. He was well known in Harrogate, and highly respected.

John Charles Jesser-Coope[xx]

Jesser-Coope attested to the BSACo Police on 7 February 1890 and was Troop Sergeant in D Troop. He was promoted to sub-Lieutenant on 1 January 1891 at Victoria. The date he left the police is not known but presumably he was on the nominal roll when he worked with Selous on the Selous Road

Following his role as assistant to Selous he was appointed a Forest Officer in the hills above Old Umtali by the BSACo and in 1892 made Inspector of Roads in the same district. Jesser-Coope cut what was known as the O’Reilly’s Road between Lesapi drift and the Odzi river that was used by Lt-Col. E.A.H. Alderson and the Imperial Forces in 1896 during the Mashona Uprising or First Chimurenga.[xxi] [See the article Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] This enabled the Imperial Forces to by-pass the Devil’s Pass where they believed they might be ambushed by Chief Makoni’s forces.

He took part in the Jameson Raid as a Lieutenant and was captured at Doornkop before being sent to England. Back at Mafeking at the time of the Matabele Uprising or Umvukela, he raised a unit of scouts before being ordered to raise Bamangwato levies from Chief Khama. His scouts were in action with Plumer’s forces at Ntaba zika Mambo [See the article Battle of Ntaba zika Mambo, Manyanga or Mambo Hills under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The scouts fought in the Matobo under Jesser-Coope, now promoted to Captain, at Babayan’s stronghold on 20 July 1896 and at Inugu, known as Laing’s graveyard. [See David Tyrie-Laing and the near-disaster Matobo Hills engagement in the 1896 Matabele Uprising or Umvukela under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] The scouts also fought at the battle of Tshingengoma or Sikombo’s stronghold where his great friend Hubert Hervey[xxii] was mortally wounded. [See the Battle of Tshingengoma or Sikombo’s stronghold under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

He was transport officer for a large patrol that left Fort Filabusi early in 1897 for the Mpateni area of Belingwe to search for arms and established Fort Mpateni.

Jesser-Cope served in the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers during the second Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 and was present at the Relief of Mafeking.

In 1902 he joined the Public Works Department in Matabeleland and was paymaster by 1904 before becoming manager of the BSACo’s Rhodesdale Estate and later the Anglo-French Ranch at Belingwe.

He served with the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment in German East Africa, now Tanzania in 1915 commanding C Company and was promoted to Major. In August 1916 he was in command of the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment but had to resign through ill-health in May 1917.

In February 1929 he commanded the special constables during the Bulawayo railway strike and was a well-known and much respected figure. Died in Buenos Aires, Argentina on 29 June 1950 aged 83 years.

Lieutenant (later Captain) Francis William Bruce[xxiii]

Son of Brigadier-General E.A. Bruce and also a relative of Dr G.W.H. Bruce, first Anglican Bishop of Mashonaland. After service in the Merchant Navy, he joined the Cape Mounted Rifles in 1878 and was awarded the Zulu War Medal and Clasp having been present at Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift. He then joined the Bechuanaland Border Police and was for some time in charge of the depot at Taungs where he lived with his wife and three children.

Here he supervised the making of roads and telegraph lines and built wells at Selina Road, Molepolole and Shoshong (Khama’s capital) in anticipation of troops moving north and earned a good reputation for getting things done.

He joined the BSACo Police before May 1890 and was initially stationed at Macloutsie under Captain A.G. Leonard. Cpl C.H.F. Divine remembered him because Bruce’s dog had a fight with the hospital dog and Divine, who tried to separate them, was bitten on the thumb, the wound being dressed by Mother Patrick herself.

After serving at Fort Tuli with Leonard and then being posted to Fort Charter he wrote to Leonard on 5 February 1891 saying he was building a road to the coast and asked to be remembered to the members of E Troop.

On 17 April 1891 in another letter to Leonard he wrote that he was 240 kms (150 miles) beyond Umliwan’s kraal cutting a road to the Buzi river.[xxiv] He remarks: “The men are very badly off for clothes and what they have bears no resemblance to uniform, while many of them are bootless and going about bare-footed.” With him he had members of A Troop and about one thousand native labourers.

In May he was brought to Fort Salisbury in the mail cart suffering from fever and was nursed by Dr Goody and by Mother Patrick and her sisters before recovering. On 25 August 1891 he was promoted to Captain and put in charge of the BSACo Police at Old Umtali and had a temporary post as Resident Magistrate.

In December 1891 he was in charge of a police party cutting a road from Old Umtali to the site of present-day Mutare. They camped at Christmas Day in the middle of what is now Christmas Pass from which it gets its name. Local residents presented him with a testimonial when he left Umtali for England.

James Adair Campbell (1862 – 1932)[xxv]

He was the third Laird of Tullichewan, Loch Lomond and travelled widely as a young man. Appointed as Lieutenant in the Pioneer Corps on 26 May 1890 and posted to A Troop acting as Adjutant in the absence of Henry Borrow.

He was allocated 25,000 acres of land east of Salisbury which he named Melfort Estate after his ancestors the Campbells of Melfort in Argyllshire on which he built two houses named Tullichewan and Broomley, the latter named after the dower house on Loch Lomond where he was brought up. Broomley has since become corrupted to Bromley, the small trading centre on the present A3 national road between Harare and Marondera.

Campbell left Mashonaland in 1891 for America and then Scotland and does not seem to have ever returned.

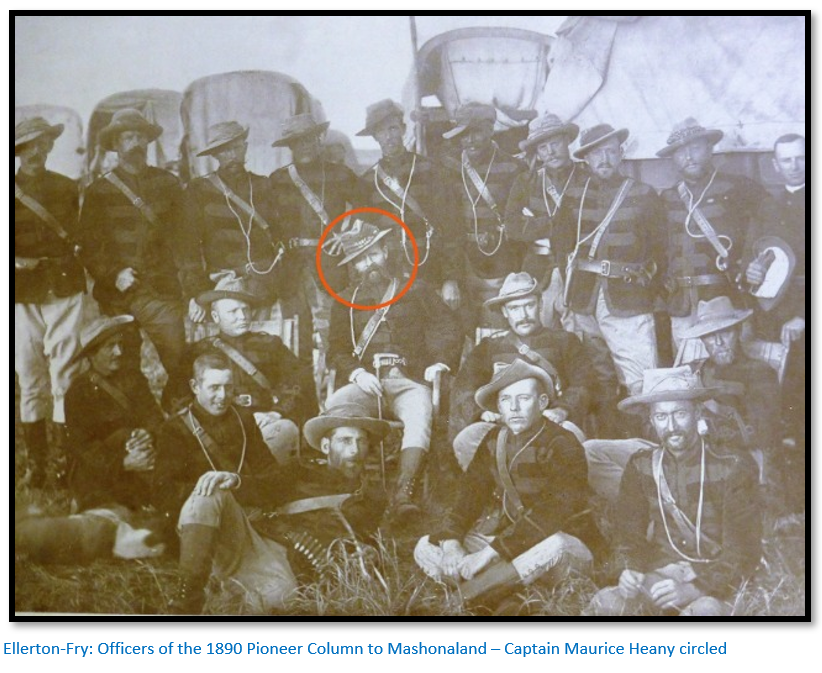

Maurice David Heany (1856 – 1927)[xxvi]

Heany, an American, came to South Africa in 1878 and took part in various campaigns before joining the Bechuanaland Border Police in 1885 and was appointed to Orderly-room Sergeant. Resigned in 1887 and joined Frank Johnson in the Bechuanaland Exploration Company. Commanded Camp Cecil in April / May 1890. He was appointed a Captain in the Pioneer Corps of A Troop.

After the occupation of Mashonaland and disbandment of the Pioneer Corps became a Director and local manager for Messrs Johnson, Heany and Borrow and was heavily involved in attempting to open up the transport road to the East Coast.

He was a Captain in the Salisbury Horse during the 1893 Matabele War. Founded Matabele Gold Reefs and Estates Co to explore for gold, involved in the diamond discoveries at Somabula and was for a period President of the Rhodesian Chamber of Mines.

He was heavily involved in Johannesburg with the Jameson Raid preparations, tried to delay Jameson leaving Pitsani, captured at Doornkop but escaped. Gave evidence in the subsequent Raid inquiry in London.

Lived in Bulawayo the remainder of his life where he became progressively blind and physically infirm, but kept his interests in business, including coal mining and public affairs. President of the Pioneers and Early Settlers Association and died after a long illness at Bulawayo Memorial Hospital 25 June 1927. Never married.

References

E.A.H. Alderson. With the Mounted Infantry and the Mashonaland Field Force (M.F.F.) 1896 Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo, 1971

A. Leslie Armstrong. Rhodesian Archaeological Expedition (1929): Excavations in Bambata Cave and Research on Prehistoric Sites in Southern Rhodesia. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Vol. 61 (Jan. - June 1931), pp. 239-276

Berenice Baynham. W.L. Armstrong Obituary in the Leeds Mercury, 31 December 1900

R. Cary. The Pioneer Corps. Galaxie Press, Salisbury 1975

J.A. Cope-Christie. Looking back over Fifty Years. Heritage of Zimbabwe publication No 6, 1986

A.S. Hickman. Men who made Rhodesia. British South Africa Company, Salisbury 1960

F.C. Selous. Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1972

E. G. Ravenstein. Notes on Mr. Selous's Map of Mashonaland and Manika. The Geographical Journal Vol. 5, No. 1 (Jan. 1895), pp. 46-49 (16 pages)

Map of Mashonaland and Manika: including the lowlands to the Zambezi and Beira. Based upon surveys made by F.C. Selous and all other available authorities; compiled by E.G. Ravenstein. Scale 1:1,000,000 Royal Geographical Society, 1895 (London: George Philip & Son) at https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/12068240

R.D. Taylor. Public Transport in the late 1890’s and early 1900’s in the then Rhodesia.

[i] Chiefs Mapondera and Temaringa

[ii] Notes on Mr. Selous's Map of Mashonaland and Manika

[iii] Theodore Bent writes: After a ride of eight miles, we reached the kraal of Kalimazondo, another son of the late 'Mtoko. It is just a circular collection of wattled huts, all joined together by a stockade. We alighted for a while here and sat in a hut, with a view to putting some leading questions to the chief concerning the state of the country. When approached on the subject of religion, Kalimazondo grew vague and uncommunicative. We let him know that we had seen the Mhondoro and knew a great deal. To all this he replied: 'I dare not tell you anything, or I should become deaf. I like my gun, and if I were to tell you anything it would be taken away, and I should be no man.'

Close to Kalimazondo's kraal we passed the remains of the hedges or sherms [scherms] which Mr. Selous and his followers had erected to protect their camp when on their visit to the old 'Mtoko, and we congratulated ourselves that it had not been our fate to be driven thus far from headquarters.

[iv] Travel and Adventure, P400

[v] Malyn Newitt writes that Sousa "made a fortune in ivory trading and his armed elephant hunters formed the nucleus of a private army which he repeatedly made available to the Portuguese authorities during the Zambesi wars."

[vi] Men who made Rhodesia, P175

[vii] Robert Cary in The Pioneer Corps has Owen Richard Armstrong (ex-Captain in the 72nd Regiment of the British Army) as attesting into the Pioneer Corps on 3 July 1890 No 160 in A Troop. After the Pioneer Corps was disbanded, he prospected in the Mazowe Valley with E.I. Pocock before working on road construction with Selous. P61

[viii] This old-fashioned word meant to lay branches and grass in bundles in boggy patches or stream beds so that the wagon wheels would get some grip and not become stuck

[ix] Sgt-Major Lyons-Montgomery cut the watershed road which starts just outside Marondera on the Harare side and goes through to Fort Charter

[x] Officially an Ordnance RML seven-pounder was a British Rifles Muzzle-loading mountain gun, which broke into two parts for carrying on mules: the seven pounds referring to the approximate weight of the shell.

[xi] Travel and Adventure, P408

[xii] Public Transport in the late 1890’s…

[xiii] Looking back over Fifty years

[xiv] James Jeffreys pegged the two earliest claims at Penhalonga in 1888 when the district was still considered to be Portuguese and named them after Count Penhalonga and Baron de Rezende of the Companhia de Moçambique

[xv] D.C. De Waal on his book With Rhodes in Mashonaland tells the same story!

[xvi] Ibid, P411

[xvii] The .303 Lee-Metford replaced the Martini-Henry rifle in 1888 although they were used for many years after including the second Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. It had a bolt-action and the magazine held eight cartridges using black powder propellant which gave clouds of white smoke and caused severe fouling of the barrel.

[xviii] Travel and Adventure, P422

[xix] Men who made Rhodesia, P368

[xx] Ibid, P272

[xxi] Notes on J.C. Jesser-Coope from Men who made Rhodesia, p272

[xxii] There is an article Hubert John Antony Hervey under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com and a book on his life Hubert Hervey: Student and Imperialist: A Memoir. The author is given as Earl Grey: Administrator of Rhodesia 1896-1898. In fact, the book was ghost-written for Earl Grey by Hugh Marshall Hole.

[xxiii] Men who made Rhodesia, P176

[xxiv] The Buzi river enters the sea north of Sofala and was a major transport route for the gold trade during the sixteenth century

[xxv] The Pioneer Corps, P45

[xxvi] Ibid, P48