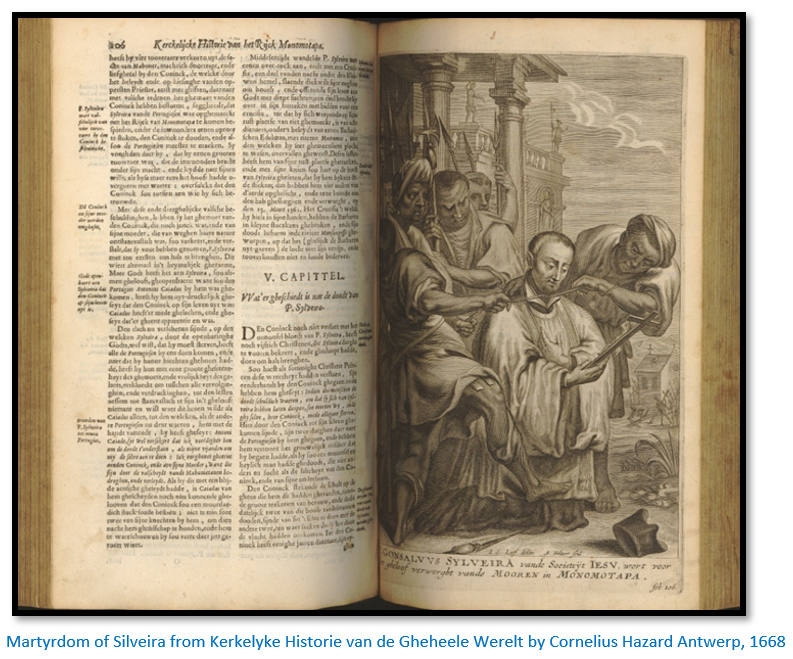

The 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J.

The 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J.

Like Antonio Fernandes, Silveira was one of the first Europeans to penetrate into the interior of Southeast Africa and to enter present-day Zimbabwe. His first mission in Africa had been to Otongue, inland of Inhambane where he left Fr. Fernandes. Both missions initially met with great success and they had baptised many converts, but then the converts had turned against them and in Gonçalo’s case he was put to death.

It seems that in the mass baptisms conducted by the Fathers they read too much into the cheerfulness, eagerness and politeness of the Africans they were meeting. Local people would rather agree with all that was said to them than cause pain to these preachers. For Silveira and his Jesuit companions they were following the model missionary of the day, the great Francis St Xavier who had died recently in 1552. These mass baptisms after very little instruction had been carried out by Xavier; often listening to a sermon or two was considered sufficient preparation for baptism and thus they were following the only missionary method they knew.

Rhodesiana Publication No 6 of 1961 has a 36 page article by Fr. W.F. Rea S.J. dedicated to the memory of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. who was martyred on 15 March 1561[i] – four hundred years previously and this article is based on Fr. Rea’s account and updated by later researchers.

Stan Mudenge believed that his death was not a conflict between Muslim and Christian spiritual values, but that Silveira’s beliefs challenged Shona social and political beliefs and those that were affected, such as the court councillors, were too powerful for Silveira and overcame the potential threat he represented.[ii]

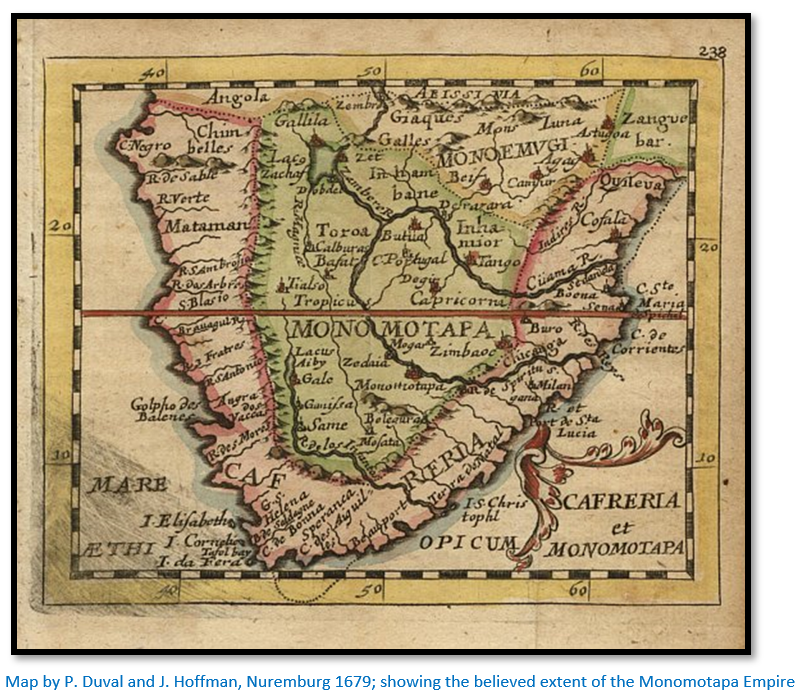

I have used the term Monomotapa rather than the Kingdom of Mutapa, Mwenemutapa, or Munhumutapa (Shona: Mwene we Mutapa) as this was the term used by the Portuguese.

The Portuguese Empire

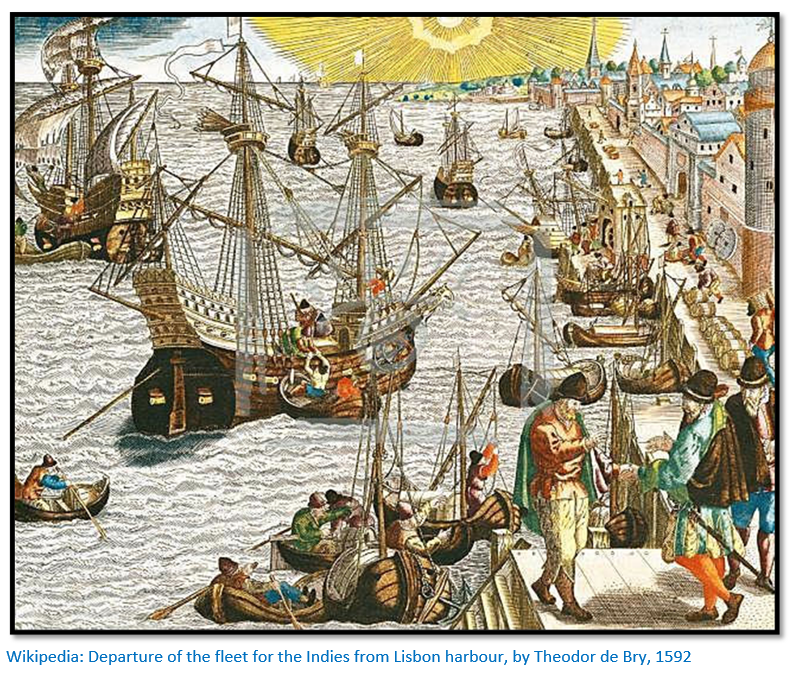

Fourteen months before Silveira was born, Vasco da Gama, the Portuguese navigator and the first to reach India around the Cape of Good Hope had died at Goa. Portuguese traders had opened up the route to East Africa with the missionaries following.

Silveira’s early life and education as a Jesuit

Born on 23 February 1526 at Almeirim near Lisbon, Portugal, the tenth child of Dom Luis da Silveira, first Count of Sortelha and Captain of the Royal Guard and Dona Beatriz Coutinho. His mother died giving birth to him and his father soon after; he was brought up by his much older sister Filipa de Vilhena and her husband, the Marquis of Távora and Lord of Mogadouro.

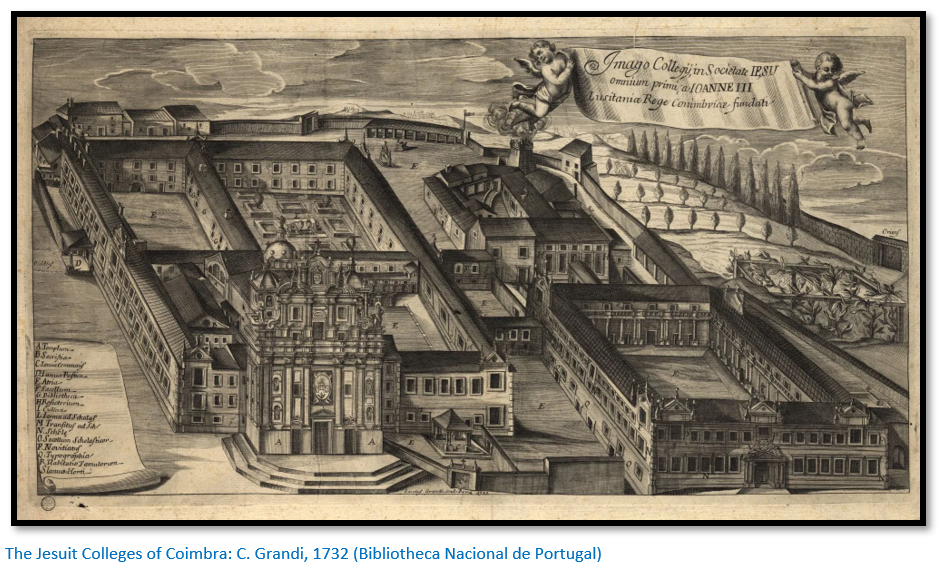

Educated by the Franciscans at the Friary of Santa Margarida until he was seventeen years old, he then continued his studies at the University of Coimbra.

At the University of Coimbra, he had met Luis de Camoens who was sent to Goa in 1552 and then to Macau, a trading outpost of the Portuguese Empire from where he returned to Goa in 1559. In Cameon’s book Lusiades, Thetis speaks to Vasco da Gama about the Monomotapa State in which Silveira will one day be martyred and says:

“Benomotapa’s vast realm see appear

Where the black savages all naked go.

Gonçalo death and hateful insult here

For the glory of his Holy Faith must know.”[iii]

But after only a year, on 9 June 1543 Silveira joined the Society of Jesus at the Jesuit college at Coimbra which had only been opened in Portugal three years earlier, but had already graduated the future St. Ignatius, St Francis Xavier and Fr. Simon Rodriguez. The Portuguese King, King John III had asked for help in spreading the Catholic faith in Portugal’s far-flung possessions and in April 1541 Xavier had sailed for India.

The Jesuit Order

Silveira lived as a Jesuit in Portugal when the Jesuits believed that their most immediate obstacle to the fuller service of God and to bringing others to the faith was their own human weakness and accordingly punished themselves to the edge of reason with the same kind of fervour that had driven Vasco da Gama and Afonso de Albuquerque to build the Portuguese Empire.

The Provincial, Fr. Simon Rodriguez did little to restrain them, teaching devotion was more important than obedience and this resulted in St. Ignatius sending the Jesuits in 1557 one of his most famous documents, his Letter on Obedience. Fr. Rea believes the indifference to government and administration of Fr. Simon Rodriguez left a deep impression on Gonçalo da Silveira which showed itself in his first appointment. He came to possess a certain hardness of spirit which had he been directed in a rather more enlightened way might have mellowed in time and shown more humanity and gentleness.[iv]

The first Jesuit martyr Fr. Antonio Criminale had been put to death in 1549 in India. St. Francis Xavier had died in China and been buried on a beach at Shangchuan Island in Guangdong. His body was taken from the island in February 1553 and temporarily buried in St. Paul's Church in Portuguese Malacca on 22 March 1553 before his corpse was moved again and shipped to the Church of Bom Jesus at Old Goa in India. Their deaths had increased the desire of other Jesuits to follow them and bring the faith to the local people and if needs be to give their lives as well.

Silveira told his fellow novices that he believed he would die a martyr; once when he was elevating the host during mass, his hands appeared to the congregation to be covered in blood and this was taken as a sign of his future martyrdom.

In 1549 he took his Doctor of Theology at the University of Gandia in Valencia, Spain and for the next four years travelled around Portugal preaching with a great fervour and sincerity and never relaxing the severe life which was the preparation for his martyrdom.

Then in 1553 he was made Rector of the Church of St Roque at Lisbon. A great celebration was held which King John III and the court attended, at which members of the Society of Jesus, including Gonçalo da Silveira took their last vows. He gained such a reputation with his preaching that filled the church to overflowing that within three years it had to be enlarged.

Appointed Provincial Superior of India

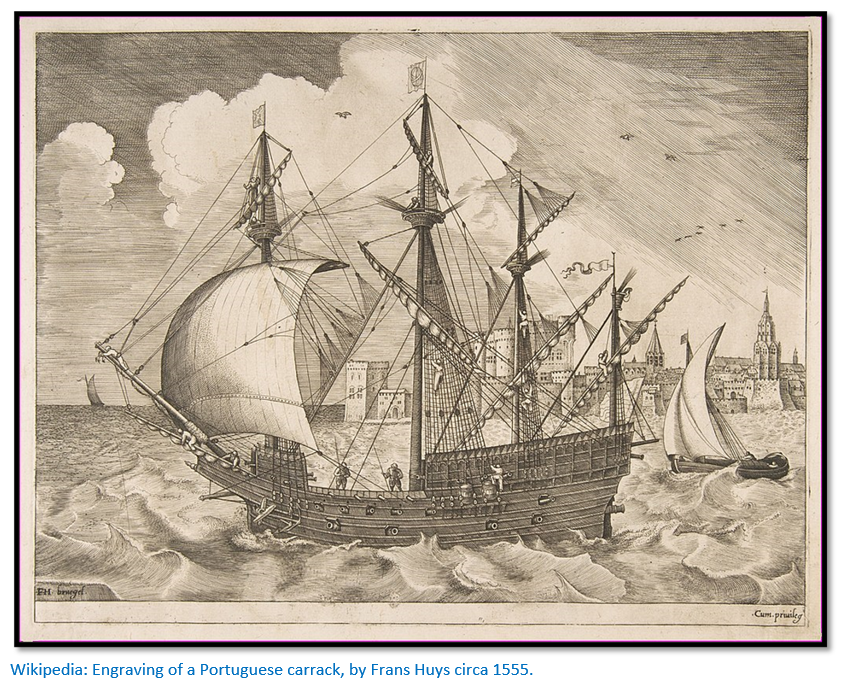

On 28 March 1556, now aged thirty years, he left for India where he had been appointed Provincial Superior of India, an appointment of three years in which he succeeded St Francis Xavier who had left in 1549. Goa was reached on 6 September after a largely uneventful voyage of five months and five days. However, “life in the cramped, reeking and verminous carracks of 400 to 500 tons, supported by mouldy food and brackish water, amid continual sickness and with death never far away, was too awful to be described.”[v] Even to a man so indifferent to body sufferings Silveira was appalled: “As death cannot be well described except by one who has attended a death bed, so the voyage from Portugal to India can only be related or even believed by one who has had that experience.”

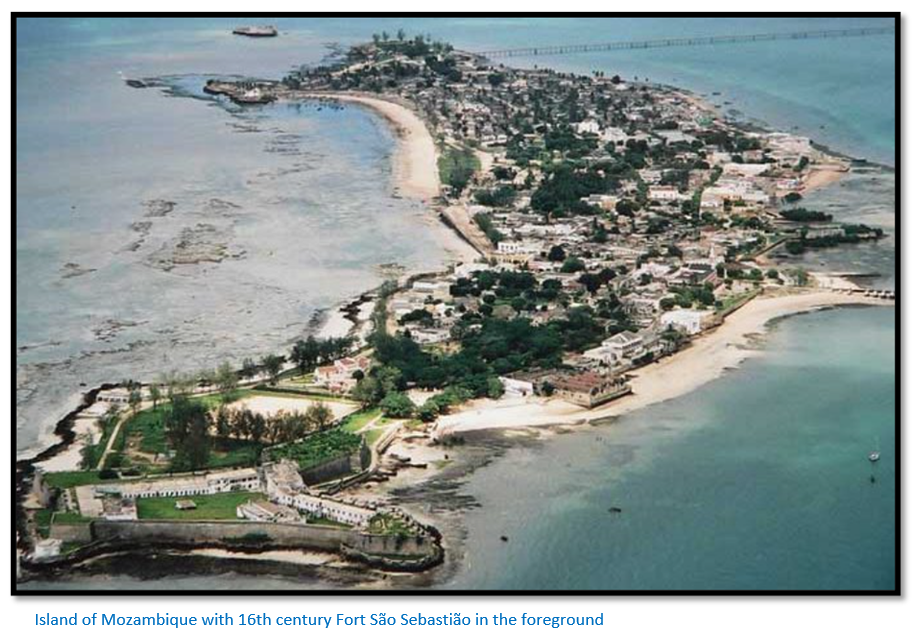

On their way they stopped at Mozambique Island as was customary and Silveira visited the shrine of Our Lady of the Ramparts and preached a rousing sermon.

Silveira at Goa

With 200 Jesuits under him he had to travel a lot as only 70 were in Goa itself; the remainder were scattered from Bassein north of Bombay (now Mumbai) to Cochin and the Fishery Coast 1,130 kms (700 miles) away in India’s extreme south and in the Molucca’s (now the Maluku Islands) and Japan. He spent months away visiting these outposts until reports of plague brought him back to Goa.

At Goa he met the Viceroy, Francisco Barreto, who seventeen years later would lead the military expedition up the Zambesi river and would die at Sena on 9 July 1573 probably of malaria about 300 kms downstream on the Zambesi from where Silveira was martyred in 1561.

Soon Silveira made a rousing appeal to the people of Goa to lift the siege of the fortress of Chaul 40 kms (25 miles) to the south of Goa which motivated them to rescue Chaul. Following this Silveira accompanied a military expedition north of Bassein to Daman which surrendered without fighting. In honour of the bloodless victory, he had a new Church built with generous support from Barreto’s successor as Viceroy, Constantine de Braganca, in honour of St Thomas the Apostle.

However, it was felt by the Society of Jesus that Silveira was not the perfect model of a Superior and lacked sympathy for those weaker than himself and so was replaced by Fr. Antonio de Quadros whom he had succeeded, three years before. Silveira retired to the noviciate to meditate and reflect and it was here that he received the call that his next mission was in Africa.

His three-year term in office as Provincial Superior was not seen as a failure as Goa converts to Christianity steadily increased from1,080 in 1557 to 3,233 in 1559.

Gonçalo da Silveira at Sofala, Mozambique 55 years after the first Portuguese permanent settlement

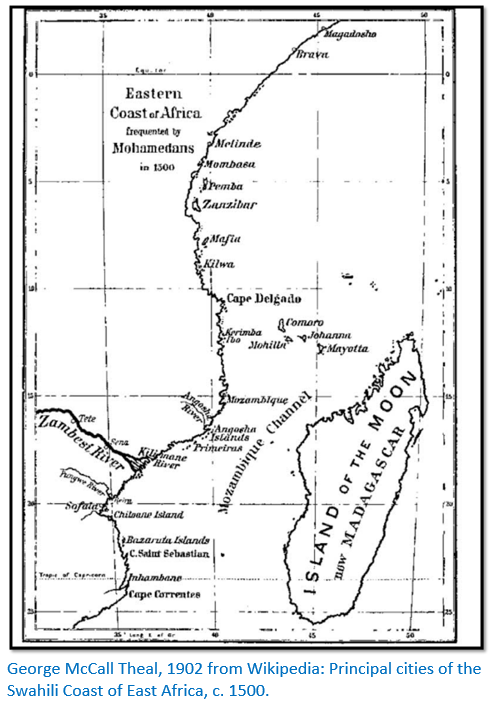

In 1505 the Portuguese made their first permanent settlement at Sofala. Two years later they took the Island of Mozambique, in 1531 they moved inland to Sena on the Zambezi (Cuama) river. From here they moved to Tete 240 kms (150 miles) upriver. In 1544 they occupied Quelimane north of the Zambezi delta and by the time Silveira arrived the Portuguese were also trading at Inhambane further down the coast.

On 4 February 1560 Silveira’s ship arrived at the Island of Mozambique and he gave thanks by going barefoot to the shrine of our Lady of the Ramparts to beg for a blessing for his mission. Typically in a hurry and rather than wait for a ship organised by the new Governor, Pantaleao de Sa, a relative of Gonçalo da Silveira, he took passage to Sofala in a zambuco, a small native craft, saying in a letter to Fr. Antonio de Quadros at Goa: “For the season in which we leave and for this navigation it is a better conveyance than a large ship and just as safe, or even more so.”[vi] However it was not an easy passage and they encountered strong winds, heavy seas and rain and it too twenty-seven days to reach Sofala on 11 March 1560. His companions, both ex-soldiers, Brother Andre de Costa and Fr. Andre Fernandes[vii] noted that the Governor’s carrack which left after them, did the journey in ten days!

Conversion of Chief Gamba and his tribe at Otongue

They only stayed for five days at the Island of Mozambique before setting off south for Inhambane near Cape Corrientes. This time Silveira was really ill – both his companions thought that if the 480 kms (300 mile) journey had been any longer he would have died. At Inhambane were five Portuguese traders who helped Brother de Costa nurse Silveira back to health and Fr. Fernandes left in advance for Otongue about 30 leagues (170 kms) journey into the interior. Otongue might be present-day Chicomo on the Inharime river as it was described as being on the banks of a great river whose waters were brackish because the river was still tidal.

The local Chief named Gamba had been trading ivory with the Portuguese at Inhambane and his son had become very friendly with them and was persuaded to visit the Island of Mozambique where he converted to Christianity. When he returned, he persuaded his father to ask for Christian missionaries and Silveira and his two companions were an obvious choice.

Fr. Fernandes’ journey took three days; his shoes hurt so much he had to walk barefoot and then he injured his knee, but he says he could not slacken, or show any sign of weakness as his African guides might think him helpless and turn against him. As soon as he reached Otongue he went down with fever, but a man named Joao Raposo who was born at Sofala with a Portuguese father and local mother, lived at Gamba’s kraal and nursed him back to health and thereafter acted as his interpreter.

Because Fr. Fernandes had white hair, the local natives thought him much older that he actually was and held him in great respect as he explained later to the Jesuits in Portugal: “seeing my hair so white they thought I must be extremely old and kept myself alive by witchcraft, being strong enough to still keep pace even with the youngest of them in walking all day in the midst of the great heat and the most simple among the people said that if I was so strong in my old age, what must I have been in my youth?”[viii] Fr. Fernandes formed a very good opinion of Chief Gamba and his four sons. After he had instructed them, they asked to be baptised, but he said this could only happen when Silveira arrived.

Silveira and da Costa finally arrived and when Fr. Fernandes met them Silveira seemed on the point of death and lay helpless on the sand too weak to raise his head. Seeing his helplessness, his bearers put him down in the bush and refused to take him any further unless he gave them all he had. In the seven weeks he spent at Otongue he never fully recovered, and da Costa was so poorly he had to return to Inhambane.

However, both men were hopeful that vast areas of the interior could be converted. Fr. Fernandes wrote: “All the women show great devotion to the picture of Our Lady and many visit the church to see it…” and he wrote to the community at Goa: “Not only people of this kingdom want to be Christians, but also those of neighbouring kingdoms and therefore, beloved brethren, prepare and know that here is a great harvest for many labourers.”

Soon both Fathers began to baptise, Chief Gamba being amongst the first was given the name Sebastian after the reigning King of Portugal. Fernandes wrote: “The king soon became a Christian, with all his household, his children and the whole of the people: they come to us, we do not need to go to them. In short, during the seven weeks that the Father (i.e., Silveira) stayed here, nearly 400 persons were baptised and, as I am informed, he continues baptising as he proceeds on his journey (back to Inhambane) In the kraals of this king I have also baptised some since he left.”

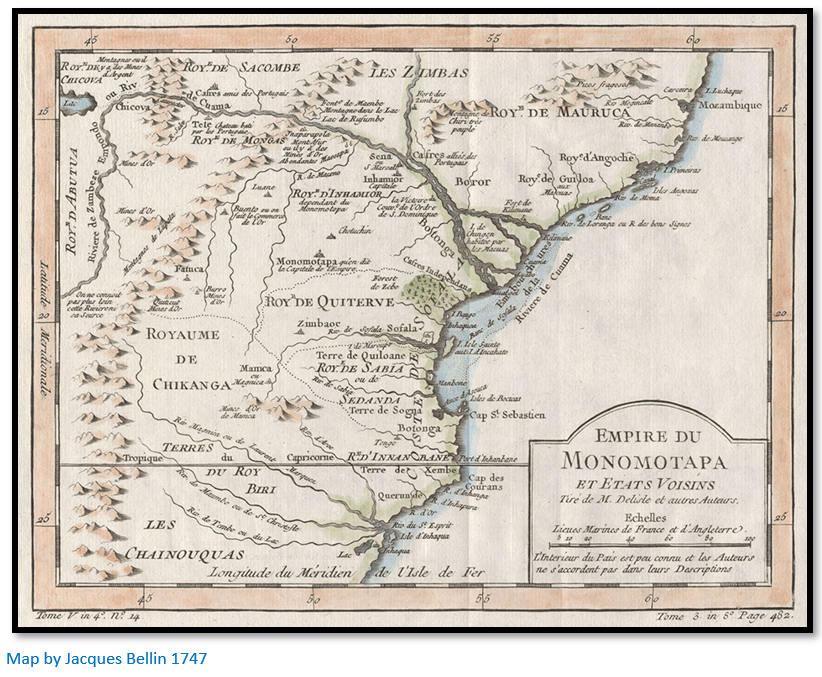

This map of Southeast Africa (primarily present-day Zimbabwe and Mozambique) shows the Zambezi (Cuama) River with the Portuguese settlements at Tete and Sena, the silver mines of Chicova, the gold mines at Azur and elsewhere, and various chieftainships. Despite these geographic sites, Bellin includes a title legend which reads: "The interior of the country is little known, and authors do not agree in their descriptions of it."

Silveira has hopes of converting the King of Monomotapa

Silveira never intended to stay very long at Otongue. He had hopes of converting the whole of Southeast Africa to Christianity and he believed the best way of achieving that was to convert the King of Monomotapa following the Latin maxim cujus regio, ejus religio meaning “whose realm, their religion” – the religion of the ruler was the religion the people followed. This left Fr. Fernandes puzzled as he wrote to his Provincial at Goa: “I cannot understand the motive of Father Dom Gonçalo for I could never get anything from him, except that a Brother and myself are sufficient here and another Father and Brother on the shore.”[ix]

Silveira returned to the coast and wrote to the College at Goa that Fernandes and da Costa were beginning to build a house and a church which would be dedicated to the Assumption. By August he was back at the Island of Mozambique preparing for his mission to Monomotapa.

Brother da Costa became so ill he had to return to Inhambane leaving Fr. Fernandes on his own to face Gamba and his people who became increasingly hostile and who now refused for Christianity to be taught. It was clear the mission had failed. What saved his life was his white hair which the Makalanga thought gave him magical powers and were afraid to touch him.

Fortunately, a letter from Goa arrived telling him to leave if the mission had no prospect of success and so Fr. Fernandes left for Inhambane and then the Island of Mozambique and then for Goa which he reached on 4 September 1562 and lived on for another 36 years.

Mission to Monomotapa

Silveira left the Island of Mozambique on 18 September 1860 accompanied by five or six Portuguese. Unfortunately, the only letter he wrote to the Provincial at Goa shortly before his death was lost when the ship carrying it to Goa was sunk on the voyage. Because of this lack of information on Gonçalo da Silveira we have to rely on the letters of a Portuguese Jesuit then at the College of Goa, Fr. Luiz Froes who was ordered by his Provincial because of the many stories being spread about of the last months of Silveira’s life to find out and publish the truth.

Froes says that Silveira left the Island of Mozambique in a pangaio, smaller than even a zambuco which needed little water to take him up the Zambezi river. During the 725 kms (450 mile) journey they endured three storms which threatened to overwhelm the boat, but finally managed to sail into the calm waters of one of the mouths of the Zambezi river. They sailed up the Zambezi river; Silveira told his companions that he must make a retreat before his work began and the eight days before they reached Sena were spent by him in seclusion.

He had to wait for about six weeks until permission was given to enter Monomotapa territory. At Sena there were a small community of Portuguese traders and Indian Christians to whom Silveira gave mass and baptized their children. He heard of a Portuguese man at Tete, Gomes Coelho, who knew the King of Monomotapa and spoke Shona and sent a message requesting that he come down to Sena.

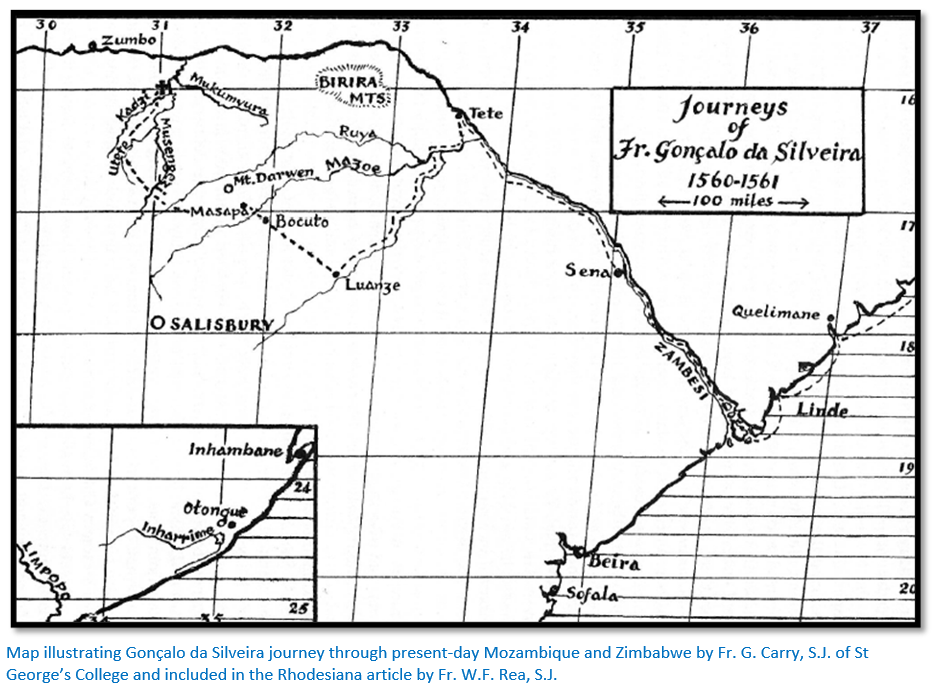

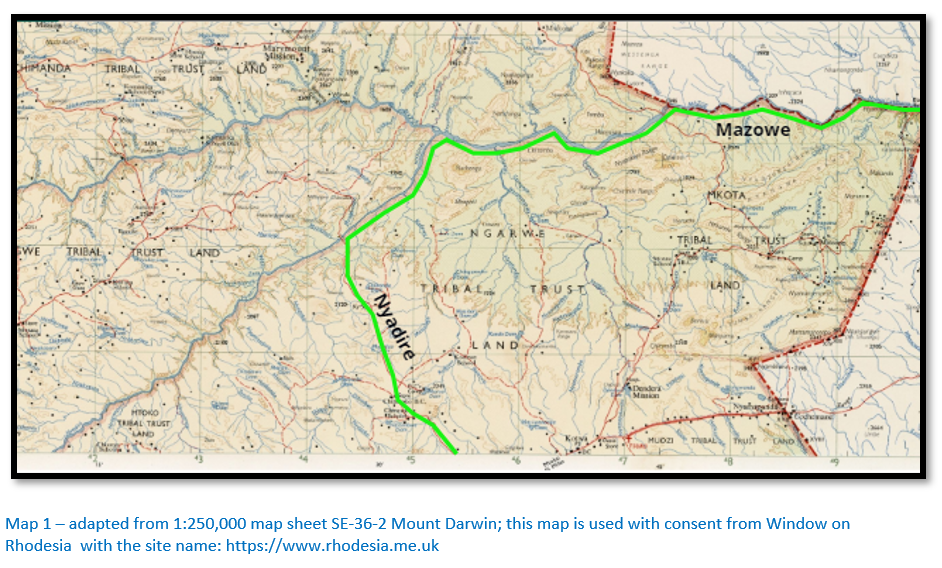

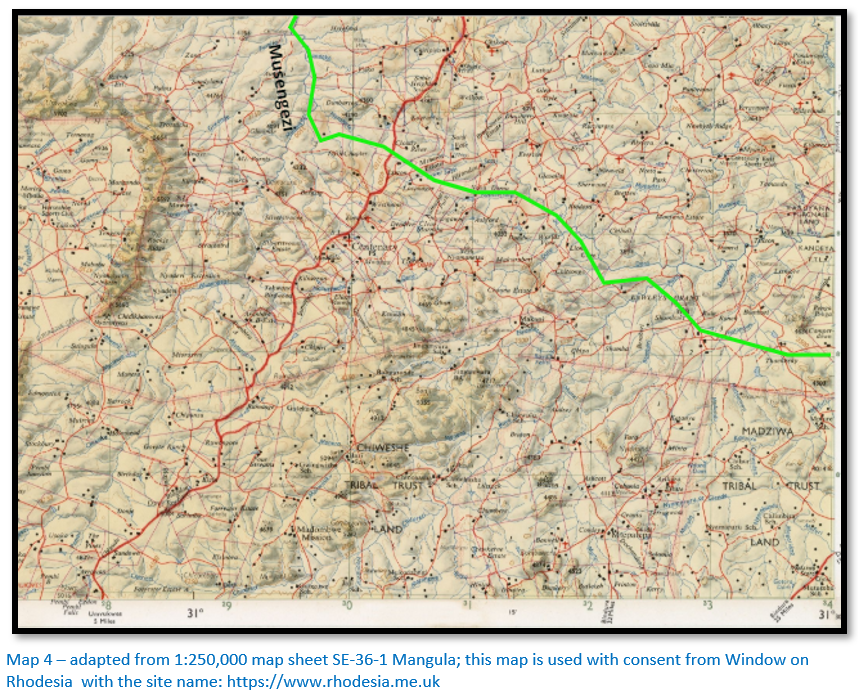

They took a boat up the Zambezi river from Sena to Tete where Silveira left Coelho and with native guides from here walked inland up the Mazowe river…this is the most obvious route to take.

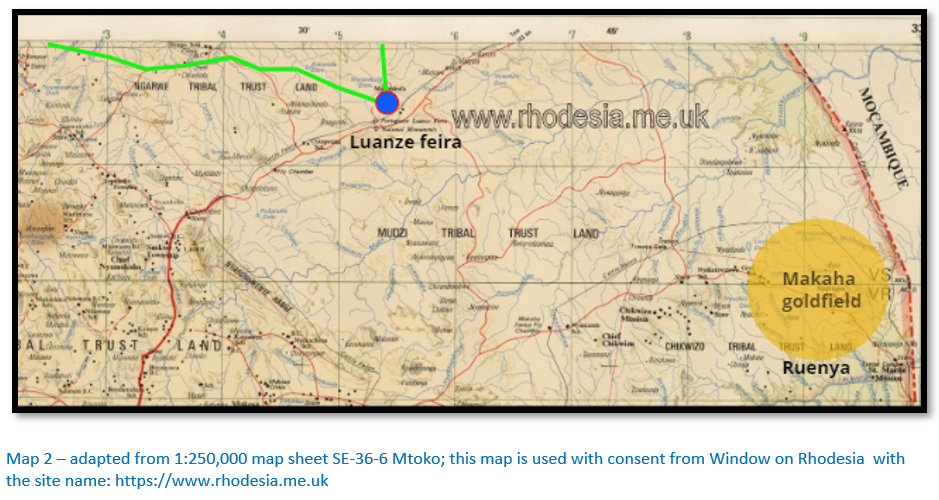

Father Rea uses some research done by the Jesuit missionaries at Marymount Mission[x] who used local oral histories to reconstruct Silveira’s most likely route. From Tete south by boat 35 kms to the mouth of the Luenya (Ruenya) river and then west by foot until the Luenya’s confluence with the Mazowe river. At this time of year unless there had been early rains there would have been comparatively little water in the Mazowe and progress along its banks would have been easy before turning south west along the Nyadire river and then due south which took him towards the Portuguese trading station (feira) at Luanze. [See the article Luanze earthworks and Church under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

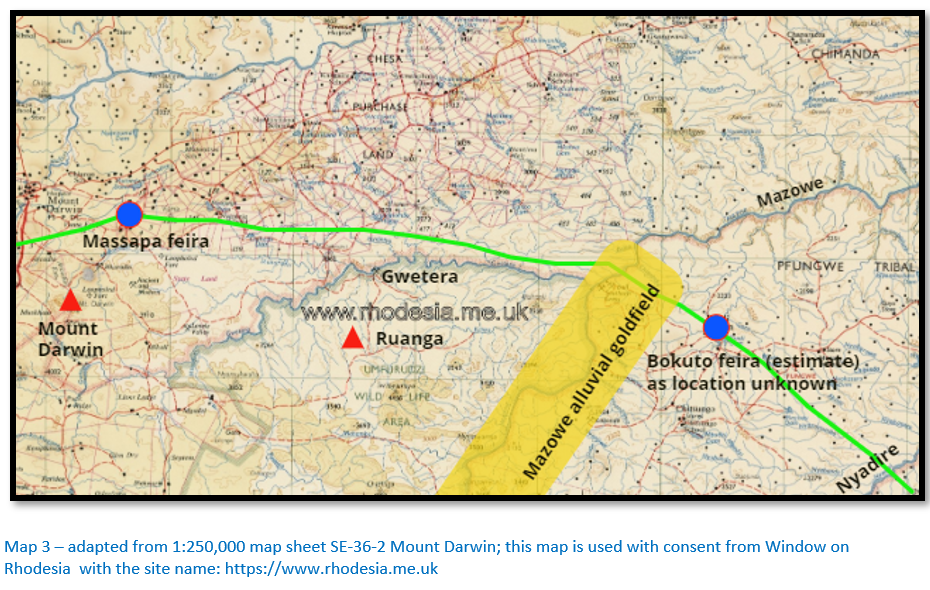

From here the journey would have been north west across the Nyadire river possibly towards the confluence of the Mazowe and Gwetera rivers as the Portuguese Bokuto (Bocuto) feira has yet to be identified but is believed to be in the Pfungwe district. This feira would have been located for the alluvial gold from the Mazowe river along the southern edge of the present-day Umfurudzi Park.

Fr. Froes relates that since Silveira could not swim and had to cross the Mazowe river he was put into a great clay pot and pushed across by his native guides and from here the journey took them to the next feira at Massapa, near present-day Mount Darwin.

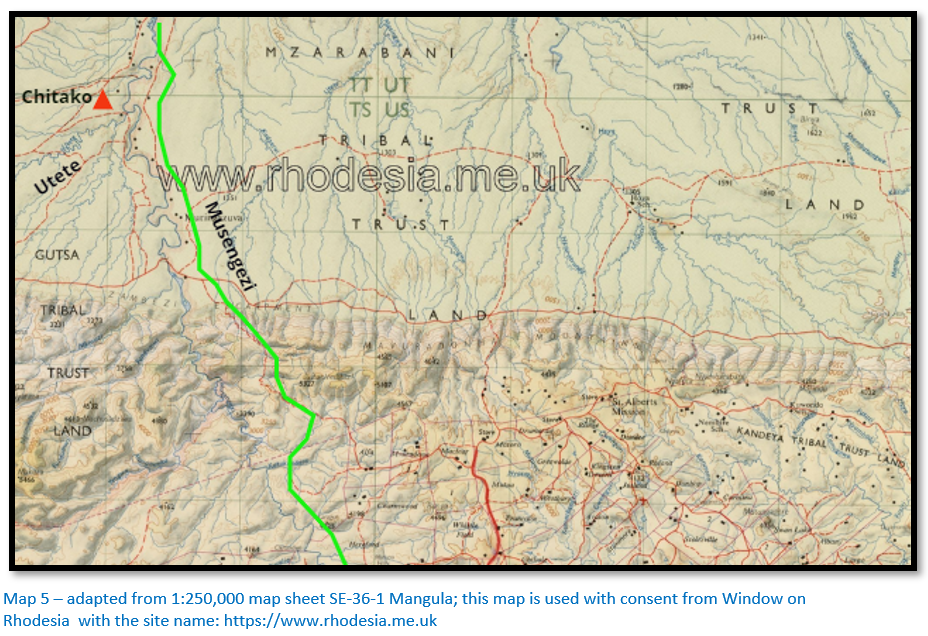

Travelling west they would journey across the upper Ruya river into the present-day Centenary district in Mashonaland Central and the valley of the Musengezi river which flowed north from here into the Zambezi river. Somewhere along its banks lay the Monomotapa’s capital as all accounts agree that Gonçalo da Silveira after being killed was thrown into the Musengezi river although the spellings differ between Monsengense, Monsengece and the Monsengesse.

Arrival on the upper Musengezi river on 24 December 1560

Froes says Silveira was on the upper reaches of the Musengezi river at a place called Chatucuy (possibly Chitako) when he met another Portuguese trader named Antonio Caiado on Christmas Eve. Caiado is important (although Fr. Rea says little about him) because he was literate and was with Silveira at the time of his death and wrote a letter describing the event. Fr. Rea states that Caiado was much trusted by the Monomotapa who used him as an intermediary in his dealings with the Portuguese.

From here the two men travelled north and on the next day, which was Christmas, Silveira said three masses and received the Monomotapa’s presents which took the form of gold, land, cattle and slaves. But Silveira politely sent them back saying that Caiado would tell the ruler that he had come in search of a spiritual gold. Clearly what he means is that he seeks the Monomotapa’s conversion to Christianity. The Monomotapa was amazed…saying he had never met a Portuguese who did not value these gifts. The next afternoon on 27 December 1560 Silveira and Caiado arrived in the Monomotapa’s presence.

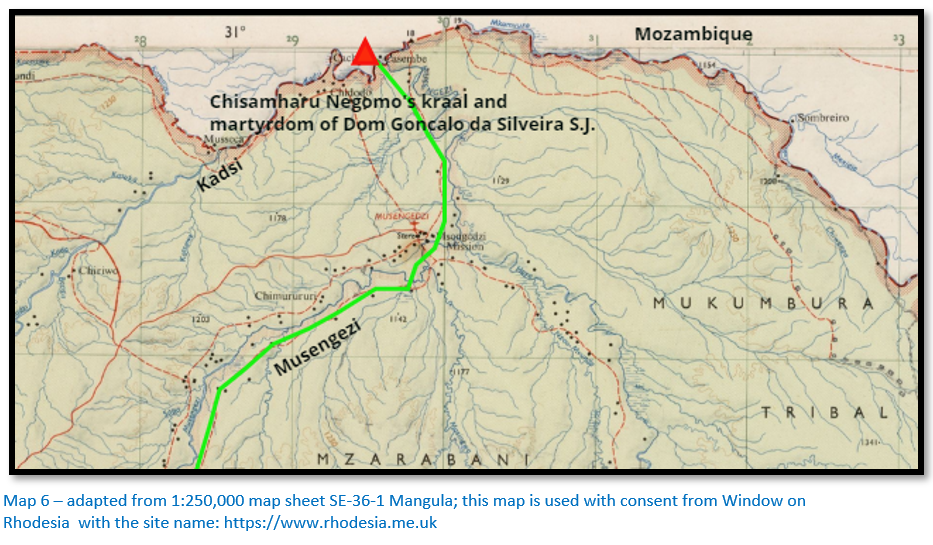

At the kraal of the Monomotapa, Chisamharu Negomo,[xi] on 26 December 1560[xii]

The Monomotapa was a young man[xiii] who had only become Chief the same year succeeding his father Chivere Nyasoro[xiv] and was already being threatened by a pretender called Sachiteve Chipute who no longer had a claim to be ruler but saw an opportunity existed. He probably hoped his welcome to this muzungu Mhondoro/Nganga[xv] would be reciprocated with strong Portuguese support against his rival. Silveira spoke to him and his mother in the privacy of the royal hut – a great honour never paid to any previous visitor. The Monomotapa’s rule extended over the northern plateau of Mashonaland…a far cry from the huge dominions which the cartographers had painted over their maps of southern Africa.

Within a few weeks both Chisamharu Negomo and his mother had converted to Christianity. Their conversion came about because Chisamharu’s councillors saw a large picture of Our Lady in Silveira’s hut and they reported to their ruler that Silveira had a beautiful woman (muzvagwa – Shona) with him. Chisamharu asked to see her, so Silveira took the Virgin Mary’s picture to him saying she was the Mother of God; to whom everyone on earth, including kings and emperors were subject. When Chisamharu begged to have it, he was given the picture and Silveira made a shrine for it in Chisamharu’s hut.

After getting the picture Chisamharu thought the Lady appeared to him and smiled. Then she spoke, but he could not understand what she said. He told Silveira about this who replied that when he became a Christian, he would understand what she said. So, he sent Antonio Caiado to Silveira to tell him that he and his mother wanted to be baptised.

Silveira instructed Chisamharu and his mother twice a day over a period of two weeks – much longer than his usual practice - then baptised Chisamharu and his mother giving them the names of Dom Sebastião and Donna Maria. To celebrate his baptism Chisamharu gave Silveira a hundred head of cattle. Silveira ordered them killed and given to those in need. This made him very popular with Chisamharu’s people and 300 of them asked to be instructed and then baptised which was done.

“The priest was so well liked by the King and all the men of rank that they always sought his company and nobles and plebeians alike wanted to become Christians.”[xvi]

Silveira’s success would bring great reward to Portugal and the Catholic Church

Stan Mudenge says the Swahili Muslim merchants and Portuguese traders on the lower Zambezi at the time enjoyed an easy-going relationship. Silveira writes of some Portuguese as being “corrupted by the infernal sect of Mohamed and even mixed with the pestilential Jews.”[xvii] Silveira saw Muslims and Islam as enemies of his faith and his country. Once converted to Christianity the ruler would favour the Portuguese traders and expel or reduce the number of Muslims permitted in his territory.

At Sofala and Quelimane, Sena and Tete the Portuguese had the numbers to control the trade network, but inland in the sixteenth century the Swahili merchants outnumbered the Portuguese and dominated the gold trading network. However, with the Mutapa and his councillors converted to Christianity then the tables would be turned on the Muslims and Mudenge describes Silveira in this sense as “a one-man army.”[xviii]

Would this end like the conversion of Gamba at Otongue?

This appeared to be heading to the same conclusion. Chisamharu would get tired of the novelty of Christian teaching and would become disgruntled when he realised the Portuguese were not likely to be sending armed support and finally would neglect and abandon Silveira so that he died of exposure and starvation.

Silveira’s end was precipitated by the presence of Swahili traders whom the Portuguese called mouros, especially a Muslim teacher called Mingame whom Fr. Froes names as their leader, who were afraid that the Portuguese would threaten their hold on the gold trading network they had controlled for centuries. They and the Monomotapa’s spiritual advisers made a number of allegations:

(1)They told Chisamharu that Silveira had visited his rival Sachiteve Chipute and left his followers with him before visiting Chisamharu.

(2)They also said the Viceroy of India and the Governor of Mozambique had sent Silveira to spy on his kingdom and prepare it for Portuguese conquest which he would do by baptism and make his people incapable of resistance. They said the Portuguese had done the same at Sofala in 1505.

(3)Finally, they alleged Silveira was a sorcerer, muroyi, who had come to bring drought and famine to the country, to begin a civil war and to oust the Chief.

True to form Silveira had probably also alienated the traditional spiritual leaders of the Shona – Mhondoro and Ngangas, who would have been described as frauds and agents of the Devil by him.[xix] Equally some of the officials at court, the mbokorume, who had refused to be baptised, would be feeling threatened by the influence Silveira held over Chisamharu.

They recommended “That His Highness should look after himself and not let him go away alive, otherwise he would leave unnoticed and the people of the land would kill each other and not know whence death came.”[xx]

The martyrdom of Gonçalo da Silveira on 15 March 1561

Chisamharu was shaken and called his mother and his councillors who were all greatly uneasy. They asked an Nganga, who confirmed everything that had been said about Silveira and from that moment his fate was sealed.

Silveira heard the whispers being spread about him and Antonio Caiado said Silveira told him: “I know that the chief will kill me, but I am delighted to receive so happy an end from the hand of God.” He was urged to leave immediately but refused to do so.

Caiado went to Chisamharu to establish the truth and was told: “If you have any belongings in the Father’s hut, remove them, for I must order him to be killed.”[xxi]

On 14 March 1561, Caiado saw Chisamharu once again who said that he and his mother would discuss Silveira’s future the next day, but on the same night gave orders that Silveira should be killed before the sun rose the following day.

Silveira was resigned to his fate. On the Saturday he told Antonio Caiado to collect all the Portuguese in the neighbourhood so that he could hear their confessions and give them communion. They had not come by midday and so he said mass alone.

In the afternoon he baptised another fifty local people. When the Portuguese traders finally arrived, he absolved them and asked them to keep the items used in mass, only keeping for himself a cassock, surplice and a crucifix.

Caiado instructed two of his servants to remain with Silveira throughout the night. Silveira’s last words to him were: “Antonio Caiado, it is certain that I am more ready to die than the Mohammedans are to kill me. I forgive the king who is young and his mother because the Moors have deceived them.”

Reports by Antonio Caiado’s servants of the murder on 15 March 1561[xxii]

They said that until midnight Silveira had walked up and down in front of his hut, at times looking up to heaven and stretching his arms in the form of a cross and sighing. Then he went to his hut and prayed before sleeping on his reed mat which he used as a bed.

The murderers rushed his hut once he was asleep and killed him in the traditional way a muroyi or sorcerer was killed. Silveira was thrown on his front by the Mucurume,[xxiii] the Monomotapa’s right-hand man and another four men lifted him up by his arms and legs. A rope was looped around his neck and pulled from both sides by two more men; blood poured from his nose and mouth and he was strangled until death. Then his body was dragged with a rope to the nearby Musengezi river and thrown in. He was just 35 years old.

Caiado’s servants fled from the scene in terror.

The aftermath

According to local reports a lightning strike that day hit the perimeter fence and partly destroyed the door of the royal hut. Terrified, Chisamharu had ordered the fifty local people who had been baptised the previous day to be put to death. However, his councillors said they had also had water poured on their heads and should be put to death; indeed, the chief and his mother had also been baptised. Now thoroughly confused, Chisamharu withdrew the order and retreated to the royal hut.

It was said that Silveira’s death was followed by two years of severe famine caused by an endless swarm of locusts that resulted in the death of many people. Indeed, Chisamharu reportedly even had his mother executed for her part in supporting Silveira’s death.[xxiv]

Revenge on the Swahili traders

The remaining Portuguese now told Chisamharu that the Portuguese would surely seek to avenge Gonçalo da Silveira’s murder. He put the blame on the Swahili traders and had two killed, Mingame and another managed to escape.

Further Catholic attempts to spread the Gospel

Ten years after Silveira’s death two Jesuits, Fr. Francisco de Monclaros and Fr. Estavao Lopes accompanied Francisco Barreto’s military expeditionary force to conquer the Monomotapa, capture his gold mines and as an act of retaliation for the murder of Gonçalo da Silveira. They sent back useful reports on the conditions in northern Mashonaland in which they advised against further missionary activity on the Zambezi except at the established towns of Sena and Tete.

In 1577 some Dominicans had come from India and from 1607 to 1610 the two orders worked together. Then in 1610 instructions came from the King of Portugal Phillip II that the Jesuits should leave the country south of the Zambezi river to the Dominicans whose area of responsibility would include the Monomotapa’s dominions.

In May 1629 the Dominicans converted the then Monomotapa, Mavuru II and he continued to help the missionaries and in 1652 his successor also converted to Christianity. However, there was never any broad support for the Catholic Church and by 1667 there were only six Dominicans in the region.

In September 1759 the Jesuits were expelled from their mission churches in Mozambique and all their other territories allegedly because their brethren in Portugal had been plotting against the King of Portugal.

The Dominicans continued their work in this very remote, difficult and malaria-ridden apostolate until 1775 when they were recalled to Goa.

It was not until 1879, over a hundred years later, that Fr. H. Depelchin entered present-day Zimbabwe on a new mission and two years later the Jesuits were again asked to do missionary work along the Zambezi river.

In 1905, 344 years after the death of Fr. da Silveira, the official investigation to establish his martyrdom and to open an investigation was started by the Catholic Church.

Maps showing the possible route through present-day Zimbabwe of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J.

Note: all the contemporary accounts state that the site of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira’s martyrdom took place near the confluence of the Musengezi and Kadsi rivers – if so, this is just outside the boundary of present-day Zimbabwe and at the edge of Lake Cahora Bassa.

Local Cultural Conceptualizations of the martyrdom of Gonçalo da Silveira in 1561

Gai Roufe in an interesting article explains that contemporary and later accounts of Silveira’s murder were justified by the spiritual advisers of the Monomotapa on account of his being a wizard or sorcerer (muroyi) In local Shona terms there are Nganga, with positive meanings and muroyi, with negative meanings. In Portuguese accounts these were both translated as feiteceiro (sorcerer)…Roufe argues that the claims that Silveira’s murder was because he was a sorcerer or seen as an envoy of the Portuguese are simplistic and culturally biased.

The original interpretations are based on letters from Antonio Caiado the translator who was present at the murder and another by Luiz Frois, head of the Jesuit College of St. Sao Paulo in Goa, both in 1561. In his letter Frois describes Caiado as: "Portuguese, a good friend and familiar with the king in Manamotapa" and also gives the testimony of Caiado's two servants who were the eyewitnesses.

Roufe believes Caiado demonstrates cultural bias by stating the Ngangas were Muslim and manipulated the young Monomotapa with false accusations “to maintain their political and religious influence on the ruler” and gives a somewhat fuller description than that of Fr. Rea of the reasons the Ngangas gave to prove their allegations:

(1)Silveira’s plan was to kill the Monomotapa and the entire population of the land by converting them to become Christians and by “splashing water on their heads” whilst uttering the words of the Langarios (Portuguese) These actions would bring them all under Silveira’s and Portugal’s control.

(2)Silveira carried with him a bone stolen from a grave and many other magic potions that he intended to use to kill the king.

(3)He would cause drought and famine.

(4)If Silveira was not killed, he would suddenly disappear and then the people of the land would begin killing each other without any apparent reason.

(5)His body should be thrown into the river and not left exposed to the sun as it would poison the people.

(6)Silveira was seen walking naked from the waist up near the precinct of the king’s hut; he had taken wood bark from the King’s perimeter fence and tied them to his shirt. Because of these acts, lightning descended from the sky and broke a pole from the king’s doorway.

Other themes are also examined in the article. For example, in Diogo de Couto’s account of the battle that took place in 1571 between the Mongazes and the Portuguese army led by Francisco Barreto, there is a description of a sorcerer who was female and carried out similar actions as those which Silveira was accused by the Ngangas. The sorcerer had potions inside a gourd which she persuaded the Mongazes would defeat the Portuguese.

Diogo de Couto wrote about this sorcerer: “When they were near us, she took out from a gourd a small amount of powder, and tossed it into the air, with these she made the Mongas believe that she will blind all of our men and we will all fall into their hands [...].” Gonçalo da Silveira was accused that the water he splashed on the heads of the people during baptism was the potion he used to gain control over them. Roufe noted that the word fumbi in the local dialect meant both dust and splashed water.[xxv]

Roufe also explains that a peaceful succession to the Monomotapa throne was a rare occurrence and that the throne was usually won by usurpation or war. Moreover, the vanquished Monomotapa, the Nevinga, is usually executed by strangulation with a ribbon, referred to as a Mucheca, by the Matumbzes of the Monomotapa. One of the titles of the Matumbzes is the Bucurume; the only person involved in the murder of Gonçalo da Silveira identified by the two servants of Caiado who witnessed the act was the Bucurume.

The strangulation ritual is described in the Descripção do Imperio de Manamotapa daquem do rio Zambeze where the anonymous author claims that: “When the emperor is defeated in war, he cannot flee, and the victor cannot kill him in another manner than strangulation [...] the victor sends to build a big house made out of wood, and after this house is built the lords and priests grasp the defeated emperor from one side and from another, they take him into that house and strangle him.”[xxvi]

References

Catholic Encyclopaedia. https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13792b.htm

The Jesuits Prayer Ministry, Singapore https://www.jesuit.org.sg/mar-15th-goncalo-da-silveira-sj/

G. Roufe. The Reasons for a Murder: Local Cultural Conceptualizations of the Martyrdom of Gonçalo da Silveira in 1561. Cahiers d ‘Études Africaines Vol. 55, Cahier 219, 2015

S.I.G. Mudenge. A Political History of Munhumutapa c.1400 – 1902. Zimbabwe Publishing House. Harare 1988

W.F. Rea S.J. Rhodesia’s First Martyr: Gonçalo da Silveira. Rhodesiana Publication No. 6, 1961

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_India_Armadas

[i] Fr. Rea states the murder was on 17 March, but contemporary letters state the 15 March 1561

[ii] Mudenge, P69

[iii] Rhodesia’s First Martyr, P3

[iv] Ibid, P5

[v] Ibid, P9

[vi] Ibid, P14

[vii] In later life Diogo do Couto joint author with Joao de Barros of the Decades, one of the greatest Portuguese historical works, wrote: “He afterwards lived in this city of Goa for many years, giving a rare example of virtue, and died here at the age of 90. He was amongst those who entered the Company of Jesus in the time of the Blessed Father Ignatius, its founder. Much might be said of his virtues, life and death, for we were familiar with him for many years and were very devoted to him.”

[viii] Ibid, P16

[ix] Ibid, P20

[x] Marymount Mission is at 16° 39.6´ 32"S 32° 25´45.6"E and just 10 kms north of the Mazowe river which enters Zimbabwe 40 kms to the east. Approximately 50 kms south is the Portuguese trading post at Luanze.

[xi] Stan Mudenge in A Political History calls him Negomo Mupunzagutu (Chisamharu) [Sebastião] P376

[xii] Ibid, P64. Mudenge states the 1 January 1561

[xiii] Ibid, P62. Mudenge calls Negomo an impressionable and inexperienced youth.

[xiv] Ibid, P61-62. Nyandoro Mukomohasha should have succeeded but allowed Negomo Mupunzagutu to succeed on condition that one of Mukomohasha’s sons succeeded Negomo.

[xv] Ibid, P63. White spirit medium / diviner

[xvi] Padre Luis Frois, Goa, 15 December 1561

[xvii] Mudenge, P63

[xviii] Ibid, P63

[xix] Ibid, P65

[xx] Ibid, P67

[xxi] Rhodesia’s First Martyr, P33

[xxii] Gai Roufe states the murder took place on the night of Friday 15 March 1561. Both the Catholic Encyclopaedia and Wikipedia state 6 March 1561

[xxiii] The Reasons for a Murder, P469

[xxiv] Mudenge, P69

[xxv] The reasons for a Murder, P477

[xxvi] Ibid, P481