Thomas Leask’s Life and Diaries describing Matabeleland and Mashonaland in the 1860’s

Some background

Thomas Leask (1839 – 1912) was born at Aglath, Stenness in the Orkney Islands on 12 October 1839, the son of a farmer and as a child must have known the nearby standing stones of Stenness which date from the Neolithic age and the sea lochs a few miles away

He went to a local school, after which many Orcadians found jobs at sea; Walter Scott wrote: “no man is anything with us island folks, unless he can hand, reef and steer.” A nephew, Captain William Leask, master of the sailing ship City of Florence rounded Cape Horn forty-two times, his brother Robert became harbour-master in Melbourne, Australia. Another brother James started a wholesale business in soft goods (blankets) in Glasgow and in his first job Thomas joined him at his warehouse. Thomas’ daughter, Miss L.M. Leask of Klerksdorp recalled: “he had no rosy prospects and the call of a new country with its excitements and the chances of making good, irresistibly drew him.” He might have joined his elder brother in Australia, instead he chose South Africa.

Soon after his twenty-second birthday on 28 October 1861 he left on the sailing ship Durban from Gravesend, London and two months and ten days later reached Durban on 9 January 1862. His diary notes the fifty-three days were: “the quickest passage on record for a sailing ship.”

The Diaries

In his preface JPR Wallis, who edited the Leask diaries, states that Leask lets surprisingly few days go by unrecorded except when he was down with fever. He seems to have written them up whilst supper was being prepared and things were quiet. His diaries reflect his character; companionable, discreet, never striving for effect; he was tolerant and fair-minded and light-hearted with local natives who liked him too.

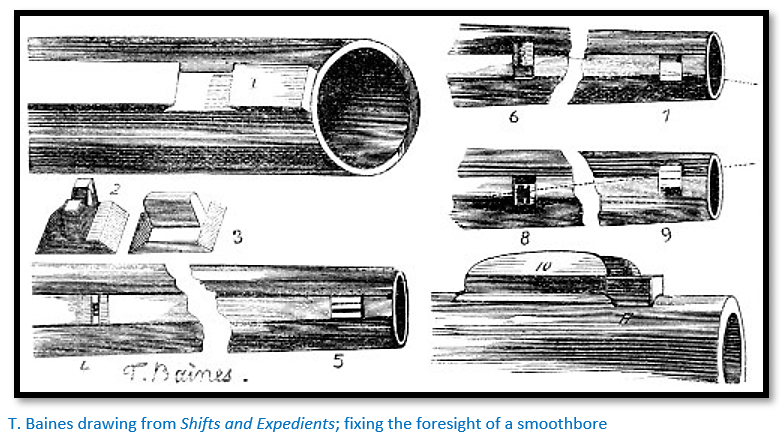

He did not have the scientific curiosity of Thomas Baines about travelling; rather he enjoyed ‘the passing scene, the chance encounter, the vagaries of character, the camp-fire gossip’[i]

Leask realised that the white man’s impact on native society was often negative. He writes: “civilization is creeping slowly onward among the natives. But civilization in its infancy is in many respects less attractive than real heathenism. Many who see her [i.e. civilization] in that stage watch her sadly and accuse her of being the cause of many evil deeds.”[ii]

For source material I have used The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask 1865 – 1870 which were edited by J.P.R. Wallis. This article includes a brief sketch of his life and selected excerpts from his diaries; for details of his journeys there are longer articles on the website www.zimfieldguide.com detailed below:

- His first journey into Bechuanaland in 1865 is not covered in detail.

- His journeys into Mashonaland and Matabeleland in 1866 and 1867 ‘My second Hunt’ are included under Bulawayo.

- His journeys to the Zambezi in 1868 and 1869 ‘My third and Fourth Hunt’ are included under Matabeleland North.

- His last journey ‘My last Hunt’ into Mashonaland in 1870 because of the death of William Hartley is included under Mashonaland West.

A life well-lived

Sir Bartle Frere was High Commissioner for Southern Africa from 1877 – 1880 and wrote this account of a stay in Klerksdorp with Leask. “Under Mr Leask’s hospitable roof he had found every refinement of modern civilization at a point where two distinct regions of commerce adjoin each other. Mr Leask’s capacious warehouses affording storage to almost every article of trade imported at Algoa Bay [Port Elizabeth] as well as to the products of the far interior, waggon loads of ivory, the spoils of the elephant, of the giraffe, of the rhinoceros and of all the gigantic game animals of Southern Africa. Anyone meeting Mr Leask’s guests and availing themselves of their ample stores of information regarding the countries to the north, might in a few weeks collect a vast amount of fresh geographical knowledge and establish relations with enterprising travellers who, in hunting or trading, penetrate to regions as yet unknown to modern geographers.”[iii]

Trading in Basutoland 1863-64

After arriving in Durban Leask soon found work in Natal trading upcountry for his firm but his diaries for the first two years are lost. Initially in a partnership with Millet he made trading visits to Basutoland in December 1863, April-May 1864 and June-December 1864. His brother James sent out soft goods from Glasgow. Leask explained: “My business among the Basutos was principally barter, giving goods in exchange for horses, oxen, sheep, goats, corn, mealies and sometimes cash. The natives bought good and useful articles such as blankets, saddles and clothing of all kinds, The women bought beads, buttons and brass wire.”[iv] His Basutoland diary falls outside the scope of this article. At the time the Basuto people under Moshesh were engaged in a land struggle with the Boers of the Orange Free State; “Mine is not an enviable situation as there is a danger of being robbed by either party, for neither would hesitate at doing it were hostilities to commence.” However it is clear that he made up his mind that he would never cross the Drakensberg mountains in winter again with its hail and snow storms.

1865

Early in 1865 he agreed to join a young friend growing coffee in Natal but the venture failed to take off . In June 1865 Leask accompanied George Phillips and Pike from Natal into the Transvaal. They were joined by Daniel Botha and Klaas Swartz on a hunting trip from Potchefstroom to Sechele’s town (Molepolole) and almost as far as Shoshong before returning to Potchefstroom in late October. Together with Phillips and James Gifford he spent the summer of 1865-66 on a farm near the town. Leask was “stony broke and £500 in debt” and his friends persuaded him to go elephant hunting with them to pay off his debtors with Phillips lending him a gun and Gifford a salted horse.[v]

Leask calls this journey into Matabeleland and Mashonaland ‘My Second Hunt’ in his diary from 4 May – 15 December 1866

4 May - Leask left Potchefstroom with Phillips, Gifford, J. Fenwick Wilkinson[vi] Phil Smith and Phillips’ ox-wagon driver Shrigley for the Marico district in two wagons. By 16 May they are at the Notwani, now Ngotwane river.

1866

13 June – “Moved on again about a hundred yards when Chapman gave a low whistle and started off at a gallop. Then for the first time I saw an elephant in his wild state. What my feelings were I cannot describe, but I shall honestly admit that when the monster, after getting the bullet, gave a scream, stuck out his monstrous ears and came thundering towards us, I say, when I saw this, fear was my strong feeling and to turn and run my only thought. And not mine alone, for everyone gave way. He only came about twenty yards and turned. We followed him and in the thick bush I lost sight of the elephant and his pursuers. Hearing a shot to the right I went in that direction and soon came up to Finaughty[vii] who was all alone with (in my opinion) a monstrous big bull. Seeing no other…I stuck to Finaughty. Certainly I could not help him much as, at the sight of the elephant, my horse got so excited that it took all my skill to manage him. He was not afraid, but awfully excited. After a while I managed to quiet him somewhat and gave the elephant a shot behind the shoulder. Tried to give him another and my horse gave a start and, big as the mark was, the bullet went wide of it. Finaughty all this time was loading and firing – it was his four-to-the-pound rifle – as quickly as possible.[viii] I loaded again, no easy job on horseback when the animal is excited and was trying to have another shot when Finaughty shouted; ‘He’s coming; look out!’ and sure enough he was coming. And an uglier animal than he looked then I never want to see. It was turn tail and run. He came about two hundred yards and stood looking as black as thunder. When he stood we stood. When he moved, we followed him, firing all the time as quickly as we could.

Matters went on in this style until he charged three times…I looked over my shoulder to see if he was still coming and through that very nearly ran afoul of a thorn tree. Consequently I gave my rifle to Finaughty, his horse being comparatively quiet though far from being a perfect shooting horse. Finaughty put seven drams of the best powder in my rifle – 14 to the lb – and gave the elephant six shots, after which he stood with his head toward us, seemingly knowing that we wanted to hit him behind his shoulder…Finaughty got off, crept around the bushes and gave him a good shot behind the shoulder . He gave one stagger and fell to rise no more. I must say I was sorry for his fall tho’ I had helped in killing him. He fought bravely and succumbed only at death.”

24 June - reach Mzilikazi’s kraal beyond the Umguza river. [Mahlokohloko kraal] “When about two miles from his place a messenger came to stop us and make particular enquiries whether there were any Boers among us. If so, they must turn back immediately…” The Hartley party arrived shortly after; both parties were here to seek Mzilikazi’s permission to go hunting.

25 June – “We all went to pay our devoirs to his majesty this morning. Found him seated in an armchair, an old balmoral cap on his head, a dirty blanket around him and a tiger kaross,[ix] outside his hut…After saluting the chief we sat down on the ground when I had ample opportunity to examine the great chief Moselekatze who has founded one of the chief tribes and has made his name terrible among the natives of all Southern Africa. There he sat, a frail palsied little old man in his second childhood, unable to move himself a yard. Still he is the chief. Every man kneels before him, every sound of his voice and every movement of his eye is instantly attended to…He spoke very little, beckoned for each one of us by turns to go and drink beer or eat meat with him, when anyone foolish enough to have a handkerchief exposed had the honour of being deprived of it by the chief. After sitting half an hour we were dismissed.”

10 Sept – “Old Baas [Henry Hartley] and Gifford went out hunting and the wagons trekked on to the river Inyati [Umniati, now Munyati] where we outspanned shortly before sundown.”

12 Sep – they re-crossed the Ngezi river and in the Mashaba Hills [the Great Dyke] managed to kill six elephants, two of whom were young calves.

14 Sep – “On our way to the wagons came across four white rhinoceros sleeping quietly under a tree…They quietly got up when we were within thirty yards and seemed not at all inclined to run for it…They walked along the path and we walked behind them, as if driving prize hogs to the show.”

3 Oct – at Mzilikazi’s kraal. “The old chief received us in a very cheerful and cordial manner. Asked how many elephants we had killed. Upon being told the number he replied: ‘That’s good for they eat my corn. He looked better than when we left him…We go to see the chief almost every morning and generally find him sitting in the goat-kraal, no matter how wet it may be. His wives carry him in his chair, set him down in the midst of the mud and water, put a tiger-skin under his feet, kindle a fire in front of him and then squat down by his side. All his attendants must sit in the dung and water; his white visitors are allowed to bring their stools.”

1867 – ‘My third Hunt’

June 1867 – they reach Mzilikazi’s kraal and stay for five months - trading and mending the dangerously ill-made flintlocks that were sold to natives.

24 Oct – “Being wearied of some five months stay at Mosilikatsi’s kraal trading” Leask, John Jennings, Fred and Tom Hartley form a hunting party for Mashonaland and leave on the Hunter’s Road.

9 Nov – their guides advise that they are close to tsetse-fly and should travel east for six days to better hunting grounds. Fred Hartley and Leask chase down a rhino “the poor animal showed no hostile feelings until he was able to run no further…it is strange that an animal with such a huge body and such short legs should be able to go at the speed they do and keep it up, seemingly for any length of time. I never heard of a rhinoceros being run down unless wounded.”

12 Nov – “Inspanned at sunrise and had not trekked far when we saw two lions trotting over the plains…One dog, a little bolder than the others, seemed to approach too near, for she sprang up and showed herself in front of Fred Hartley who gave her a bullet in the mouth whilst she was grinning at him. One growl and she lay dead.”

Leask’s journey to the Zambezi from 29 April to 14 July 1868; “My Third Hunt”

This account is written in a day-book that begins in pencil and continues in ink, but there is a gap between 28 June to 13 July 1868 brought about by his malaria fever.

18 May - Leask killed his first ostrich which he says was a great fluke as the bullet struck the ground before ricocheting up and knocking down a fine male ostrich. “Though I don’t profess to be a hunter and am willing to admit that I am a very poor marksman, still I have killed some of every sort of game that I have seen with the exception of lion…”

29 June – Van der Berg having being unsuccessful in finding Mababe Flat leaves for Wankie’s town. Leask has been sick with fever for some weeks having already sent Piet and Mavuma to trade at Wankie’s.[x] On his return Mavuma faithfully nurses him and Horn and Van der Berg[xi] do what they can. “But for the careful nursing of my good old boy Mavuma I should never have lived to leave the place…After some three days Mavuma pressed me to take some gruel. I told him it was useless as I was going to die, in fact was dying. He replied: suppose you are dying; you may as well die with something in your stomach! He looked at me so earnestly, and ill as I was, his remark amused me and to please him I said: Alright make me some gruel. I shall never forget how that dear old face brightened then. I swallowed all the gruel and not long after, like Oliver Twist, asked for more.”

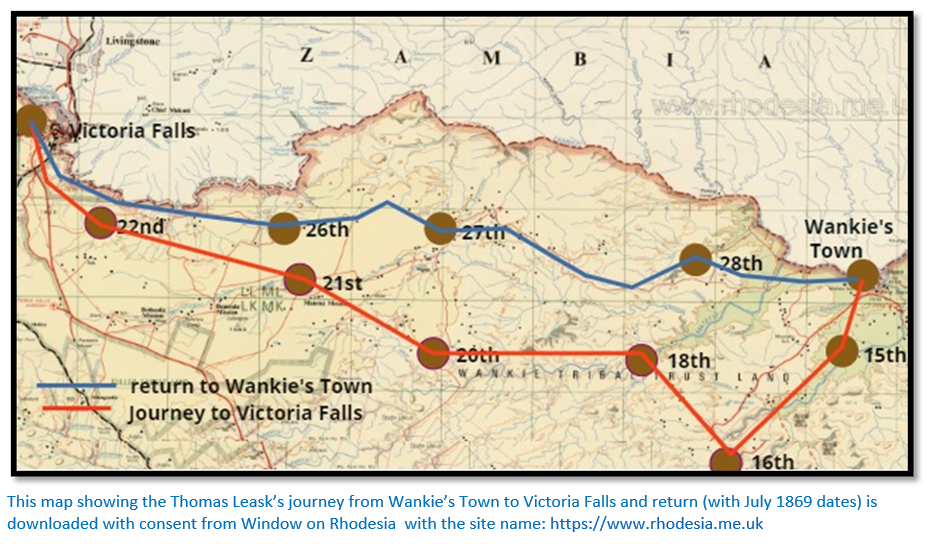

Leask’s journey to the Zambezi from February or March 29 to 12 September 1869; “My Fourth Hunt”[xii]

Leask made himself three small books from blue notepaper each measuring 21 x 13 cm (8.25 x 5.25 inches) for this journey but kept no record from leaving Potchefstroom in February / March 1869 until 8 June 1869.

Leask encounters a group of young miners from Glasgow going to Tati to work for the Glasgow and Limpopo Company. They are led by a Dr Coverley whom Leask consults professionally. “He told me I was more hypochondrial than ill” and suggested that Leask be their guide and he would be Leask’s doctor. This suited both parties and Leask’s health rapidly improved.

At Shoshong they presented Chief Macheng with a turkey; “Still I detected the old natives of the court stealing some very distrustful side-glances at him…the Chief however was thankful and said though he had not previously seen any turkeys he had heard of them.”

11 Apr – Natives told Leask that all the white people at Inyati had smallpox and they might all be dead. He did not believe them and reached Inyati Mission. A digger had died of fever, five more were sick [four of whom subsequently died] as were the Thomas family. “His wife, poor woman, is very sick though moving about; I never saw such a walking skeleton…and evidently ere long will add another to her family. Her husband sick and shall I say, silly through sickness; two of her three children just recovering from sickness…the house a heap of mud and rotten thatch, alive, literally, with rats and ants.”

Leask writes: “And why all this sickness and misery? Simply carelessness and ignorance. The houses at Inyati are enough to breed plague in wet weather. Houses did I say? They are hovels of mud and rotten thatch swarming with rats, mice, lizards, ants, etc. Every building on the place should be set on fire. All the diggers who are sick slept some time in an old tumble-down place which has not been inhabited since John Moffat left it some four or five years ago. All that slept in the house caught the fever, none of those who did not sleep in the house caught it. Again, not one of them knew how to treat the disease. No more did Thomas, and when told what to do by W and P, both of whom had had the fever themselves and seen many cases, he paid no attention to their advice.”

“If they [London Missionary Society] cannot send medical men to every mission, let them at least give their missionaries some knowledge of diseases and medicine and especially of midwifery.

2 July – They spent the night at Malonga Well [just north of Hwange National Park at Dett] where “we found three rhinoceros quietly enjoying an afternoon’s nap under a bush, one of which we shot. The beast was scarcely dead when thirty hungry heathens commenced cutting and hacking in a very careless, excited and noisy manner; a few minutes sufficed for dissecting purposes.”

23 July – “After walking three and a half hours we reached the Victoria Falls and felt satisfied…After spending some hours at the falls and getting well drenched with the spray we went about three miles up the river to the ferry. Fired some shots and the people came through at sundown. Asked them to bring some meal for sale. They promised but brought none.”

He had read Livingstone’s and Baines’s descriptions, but found the reality: “much different from what I had pictured in my mind’s eye. The placidness of the river a little above the falls, the awful yawning gulf in which the tremendous body of water falls, the deafening roar and the clouds of thick vapour which ascend and come down in a perpetual rain, the drops glittering in the sun like a shower of diamonds, the rainbows dancing about the thick evergreen dripping trees and bushes which cover the brink of the chasm opposite the fall, all combine in making a scene that for terrible grandeur cannot be surpassed.” He was disappointed in one thing: “the falls cannot be seen at once they are so broad and the vapour is so dense that they can only be seen a bit at a time.”

End Sept – They trek down the Tati river to the Tati settlement having killed about sixteen elephants and Leask returns to Potchefstroom: “where I disposed of my ivory and other goods picked up or bought in the interior. This completed I rested for some time and visited my old friends. After two or three months I made preparations for another trip to the interior which proved to be my last.”[xiii]

1870 – ‘My last Hunt’

21 May – they reach a Mashona village on the northern bank of the Umfuli hidden in the rocky kopje and defended with dry-stone walling. “The country about here is very wet. It is high and in many places rocky, but springs of water all over. It is in such places that the Mashona live, as there they can cultivate their rice of which they grow a considerable quantity. The rice gardens are in the low swampy places…Their corn and mealie gardens are on the higher ground. They also grow small grain, commonly called muunah,[xiv] ground-nuts, beans and an abundance of pumpkins, water-melons, etc. The Mashonas are an ingenious industrious people, more so than any other natives I have seen. Their iron work is good, also their weaving of sheets, bags, nets, etc., from cotton and bark. They are also advanced in the higher art of music, but they are in continual dread of the Matabele and they have no paramount chief.[xv]

Bought several bags of mealies, some nice pumpkins, etc. Red beads were all the demand. The headman sent us some mealies and beer, with an apology of allowing us to sleep hungry. Took a small present and went to visit him.”

26 May - Leask leaves the outspan at sunrise on a horse and reaches the sick party at sunset on the Chirundazi stream. “He (Hartley) was extremely weak and tho’ he knew me and spoke somewhat sensible, he looked wild. Jim (O’Donnell) was tossing about in great pain and seemed sensible. He said his bowels had not been open for three days. Tom (Maloney) was spitting continuously and calling for water. Gave them all calomel and antimonial powder and two hours afterwards jalap and rhubarb. They slept a little.”

27 May - Leask did his best with the medicines he had and the patients began to rally. “Gave them some salts and Jim at his own request two Livingstone pills. Will, I give no more purgatives. Shortly after the medicine operated on them all and they seemed much revived, but Will was very weak. They asked me to move them up towards our wagons [to join Van der Berg, Gifford and Stoffel] and as they seemed to think it would do them good, I inspanned after they had all supped a little arrowroot and trekked very gently for a short distance. They seemed a little better, but at sundown Will became insensible and unable to move.”

29 May – “He [Will] lingered til Sunday at midday and then died the same evening.”[xvi] James O’Donnell died in the evening. Of the thirteen Europeans hunting on the Umfuli river in 1870, seven went down with malaria and three died.

6 July – “After we outspanned Tom Maloney and I rode down to the old Mashona diggings on the north bank of the Umfuli where we found Mr Baines and two other white men [Baines’ cousin William Watson and his secretary Robert Jewell] in the employ of the South African Goldfields Exploration Company with two wagons. They arrived ten days ago and are putting up a house. Mr Nelson is expected with some diggers and their intention seems to be gold digging in these regions. They have named their camping place Hartley Hill. They may find payable gold, but some of them are certain to find graves if they remain the whole year. I am afraid their shafts and drives will turn to charnel houses.

Mr Baines was much surprised when we told him of the deaths and sickness of our friends and companion.”

9 July – “On Saturday we moved to the vicinity of Mr Baines’ encampment and we encamped under a small hill which we have named Constitution Hill because of my recommending those who are convalescents to climb it every morning. It is divided from Hartley Hill by a small river named [Chimbo] Mr Baines, as a tribute to the memory of our departed friends has kept the Union Jack half-mast high for some days.”

13 Sept – “There are some large hills a couple of miles above the junction of Sebakwe and Que Que [rivers] and the former river runs through a precipitous romantic-looking gorge in those hills. We climbed the largest hill and viewed the country around.”[xvii]

14 Sept – “Walked four hours and got to the wagon drift [at the Que Que river] but found no wagon there…A marauding party of Matabele passed the wagons last week. They had been to the Mashonas [Lomagundi district] other side of Umfuli, where we went to buy corn. They has some three hundred head of cattle, a great number of sheep and goats and several Mashona women and children. All the men they could get at, I suppose, they killed.”

Later life

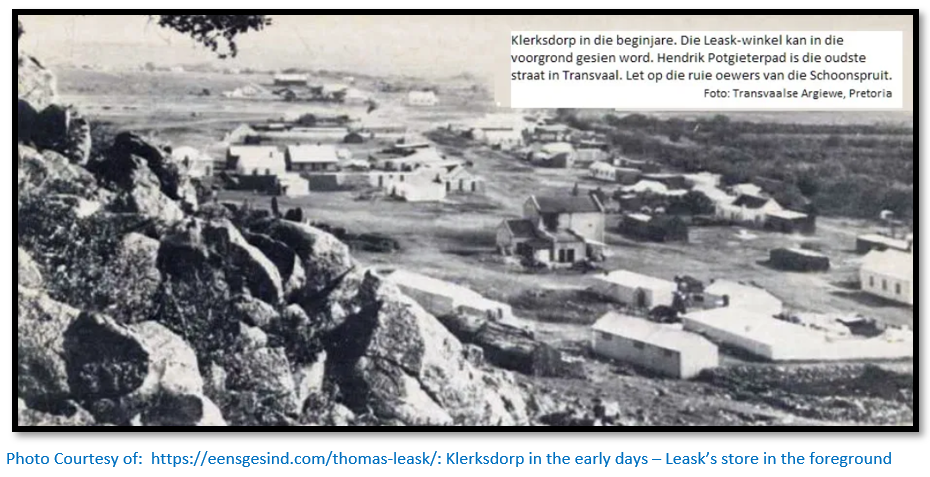

Leask gave up hunting after this last visit to Mashonaland in 1870. He made a short exploratory visit to the Vaal diamond diggings and writes: “When I returned after my last trip to Mashonaland Gifford and I intended trying our luck at the diamond fields. That was in 1871…the dry diggings now known as Kimberley, De Beers and some others had not yet been discovered. Instead of going to the diggings however I was induced by F.W. Reid to join James Taylor in taking over a store business of which Taylor was Manager and that is how I settled in Klerksdorp. I may mention that I first met Taylor at Mosilikatsi’s kraal in 1866.”[xviii]

Leask and Taylor settled into business at Klerksdorp; they were later joined by junior partners: Cato, Cruickshank & Brown; their store became the celebrated stop-off for outfitting expeditions into the interior.

1872

Leask married Lucy Salmon, a teacher in the first English school at Potchefstroom and they had five daughters and two sons. The business gradually prospered and he became the largest merchant in the region and a prominent citizen in Klerksdorp. After the death of his partner Taylor in 1878, Leask was joined by another partner called Siddle and established branch stores at Lichtenburg, Wolmaransstad and Potchefstroom. Alexander Brown managed the store at Potchefstroom, and Leask appointed two nephews to manage the others.

In addition to general groceries, Taylor & Leask handled wool, hides and skins, meat, biltong, grain and other agricultural products and provided the farming community with wire, poles, livestock, medicine and farming supplies, in an era when agricultural cooperatives did not yet exist.

Farmers soon diversified into cash crops such as maize, sorghum and sunflower and sold their products to Taylor & Leask. The firm also acted as export agents for the hunting industry, especially in the export of ivory to Europe and were regarded by the British as the leading hunting and trading outfitters in Southern Africa. They specialized in hunting equipment, weapons, ammunition, gunpowder, leather goods and men's and women's clothing.[xix]

W.M. Kerr a sportsman wrote in March 1884 as he set out for the interior with Selous; “The partners and Leask in especial were known to and liked by all the white men in the interior and when they ‘came out’ or were ‘going in’ they generally found their way to the Klerksdorp store to revive old memories and exchange news.”

1878

James Taylor set off for the interior to investigate and deal with an ivory consignment and caught fever and died at Tati. Leask had to deal with the problem which cost him £3,000 and pay interest on his partner’s capital, his widow being left with seven children, until he could buy her out.

1880

He sold large quantities of ammunition to the freebooters of Stellaland and Goshen but was unmolested during the first Anglo-Boer War of 1880 - 1881 and during the Second Boer War of 1889 – 1902 because he was a burger and remained neutral. Leask and General Cronje[xx] were both members of the Klerksdorp school board and were able to get on and trusted each other – indeed despite the troubled times he managed to keep on friendly terms with the citizens of both sides.

1881

3 June - Leask drafted an agreement which he, James Fairbairn and George Westbeech (George Phillips the other partner was not present) signed in Klerksdorp an agreement to approach Lobengula to mine for ‘gold and other minerals.’ Phillips and Fairbairn were to petition the King but nothing happened for fifteen months.

1882

1 Sep – George Westbeech wrote from his trading station at Pandamatenga complaining about Phillips and Fairbairn’s sluggishness saying Phillips was too fond of native beer and Fairbairn was a man of straw.

1884

25 Jan – “Lo Bengula, King of the Amandebele” granted the four partners “permission to dig and mine for gold and other minerals” between the Gweru and Manyame rivers. The King made his mark which was witnessed and the elephant seal was stamped on the paper. However no mining activity seems to have taken place until the next agreement is signed in 1888. [See also the article The Wood-Chapman-Francis syndicate of concession seekers under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Leask bought the farm Groenfontein to the south of the Vaal river and formed a syndicate with JF de Raedt who discovered coal there in 1873. Later the syndicate sold Groenfontein and bought Vierfontein and formed a company, Kroonstad Coal Estates.

1886

Leask became an important figure in the Klerksdorp gold mining industry and started with the help of Apie Roos.

1887

Leask was elected the first President of Klerksdorp Chamber of Mines.

1888

The firm of Leask and Taylor changed its name to Thomas Leask and Company. In the same year Leask started the Leask Gold Mining Company with a capital of £70,000. This was later developed as Western Reefs Mine and later incorporated into Vaal Reefs Gold Mine (now known as the Vaal River Operations of Anglo Gold)[xxi]

14 July – Lobengula made his mark on another agreement which permitted the four partners (Leask, Fairbairn, Phillips and Westbeech) “the sole right” to dig for gold, not within a limited area as signed in 1884, but “in my country” [i.e. throughout the King’s dominions] for which the King would receive “one half-share of the proceeds of the work.”[xxii]

A month later Charles Rudd and companions set out from Kimberley to make an agreement on behalf of Rhodes which was finally concluded in October. The Rudd concession gave the same mining rights as had been granted to Leask’s partnership but also undertook to protect Lobengula from all other concession-seekers.

[See the article under Bulawayo called Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession on the website www.Zimfieldguide.com]

11 Aug - John Smith Moffat was in 1888 assistant-Commissioner in Bechuanaland with a watching brief over British interests in Lobengula’s territory. He wrote to Leask stating that the British Government could accept no responsibility for their agreement, but he believed Lobengula had acted in good faith and would keep his word. Leask’s reply has not been preserved.

28 Nov – Moffat again writes to Leask stating that as a public official he could not side with anyone seeking favours from Lobengula. However he noted that in recent months Lobengula had been paid £500 for similar concessions and that he was learning to play one concession-seeker against another. Moreover Moffat had heard [this was a month after the Rudd concession was signed] that ”a great syndicate” was prepared to make an agreement “on an unprecedented scale” and “if necessary, to protect its own interests.” Leask and his partners were advised to merge their concession with this great syndicate. “I fancy” Moffat adds, “it will be this or nothing.”

In 1888 the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand caused rumours of its existence in the Klerksdorp area to become persistent. A local prospector found good values which prompted Leask to sign options for the mineral rights on several local farms.

Orford[xxiii] quotes Herman Guest who wrote the following in The Klerksdorp Mining Record, a local newspaper: “Mr Leask got some specimens of gold-bearing banket from the Rand and its appearance struck him as being remarkably similar to some stones he had procured on the commonage for the foundation of a house and he promptly set about searching for some of the same-looking rock. Mr J.J. Roos and others, working with Mr Leask, started prospecting operations and soon found extensive outcrops of banket along the ridge now owned by Klerksdorp Estates. It was panned and some excitement was caused by the discovery of glittering specks of the precious metal in the bottom of the dish.”

This discovery was soon common knowledge and fortune-hunters began flocking to the town with the new arrivals living in tents, wagons, shacks and huts. About 160 mining companies were registered with most going quickly into liquidation and then being re-floated by new hopefuls. The first building in the New Town was named the “Bacchanalian Bar” and soon there were 60 hotels and bars around the town.

1889

1 Feb – Leask surrendered their concession to Rhodes before Rudd in Johannesburg. George Westbeech had died on 17 July 1888 returning from Pandamatenga and been buried at the Jesuit mission station at Vleeschfontein and in November 1889 James Sivewright acting on behalf of Rhodes and Rudd agreed to pay the three remaining partners £28,000 to settle all claims under their concession.

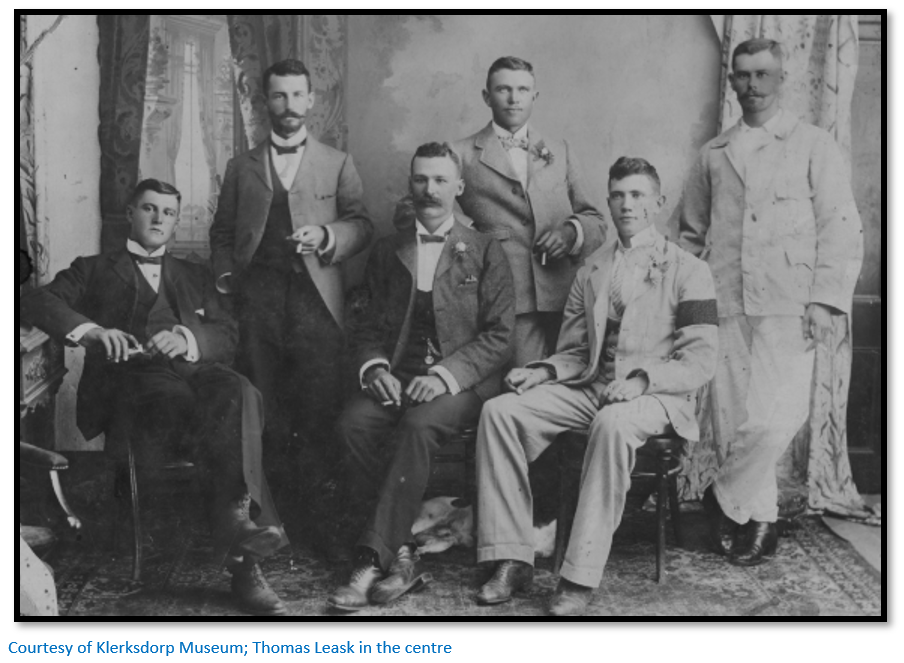

In February 1889 the Orkney Estate and Gold Mining Company Ltd named after Thomas Leask’s birthplace in Scotland issued a prospectus with a share capital of £10,000. The property covered 755 morgen (1,598 acres) and one of the Directors was Leask – the above photo maybe the founding directors.

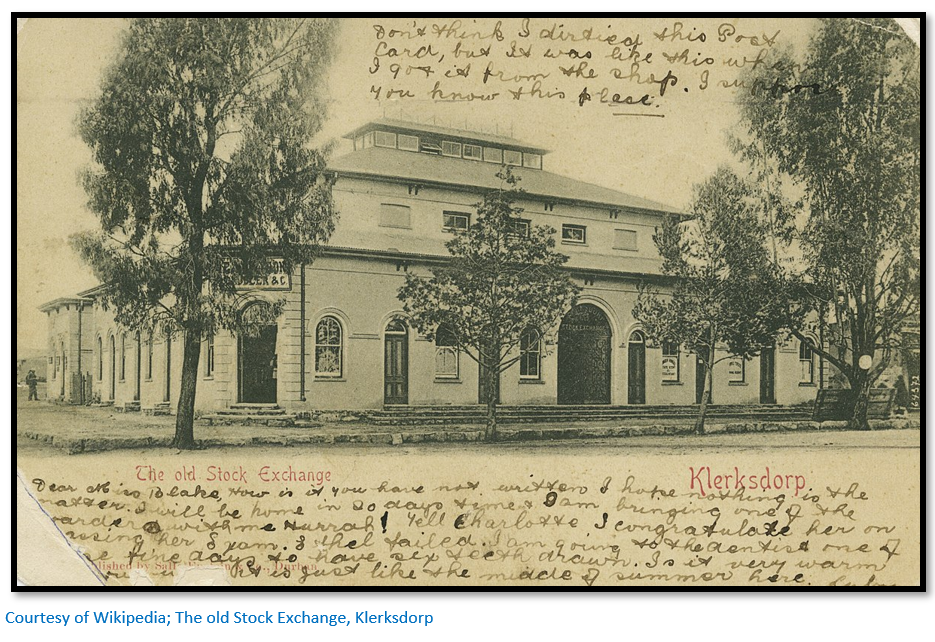

The Klerksdorp Stock Exchange was established the same year with up to £10,000 of shares being traded in a single day. Leask was appointed chairman and declared it open for business: “champagne flowed and glasses were filled.” The Exchange flourished for about a year with the dividend for the first quarter being 17.5%. However as in Barberton, another gold boom town, the Exchange did not last long and it soon became Klerksdorp’s entertainment centre and during the Second Anglo-Boer War a burgher hospital.

1890

The Klerksdorp Chamber of Mines with a membership of 10 mines was launched with Leask as President. But a slump set in and the share market totally collapsed with the brokers spending their time playing cricket, sleeping or reading novels. Most of the mining population departed for the Rand with many shopkeepers left with unpaid bills as their debtors became “fly-by-nights.” Wagons, tents, machinery and houses were almost given away.

1891

When Lord Randolph Churchill passed through Klerksdorp on his way to Mashonaland he described it as: “in a state of decay, having had an ephemeral existence. It sprang into life during the gold-mining boom of some four years ago. The ground all around it for a considerable space was hastily pegged off in mining claims, companies were floated with large capital, shares were tossed up to a premium by the promoter, just as a Japanese conjuror with a fan causes bits of paper to ascend in the air, then came the crash. All was over and a large pretentious stock exchange, tenanted now only by the dog, the cat, the pig and the fowl, tell the interesting story of an African golden dream.”[xxiv]

Clearly Randolph Churchill was working himself up into a negative frame of mind for his forthcoming tour of Mashonaland! The introduction of the McArthur Forrest cyanide process made possible the recovery of the gold from ore which had previously been lost signalled a new era of prosperity for Klerksdorp.[xxv]

1892

In December 1892 Thomas Leask, now managing director of the Nooitgedacht mine told an assembled crowd that 1,000 ounces of gold had been extracted to date as his daughter Lulu started the engine of the newly-installed five-stamp battery. The new cyanide process increased gold output from 7,000 ounces in 1890 to a phenomenal 71,776 ounces (2,232 kgs) in 1895 when there were 25 operating mines in the Klerksdorp area.

1902

After his retirement, Leask left the business to his two sons who subsequently sold it. The firm re-opened under the management of one of his sons in 1926 and closed down finally in 1953 after many years’ service to the community.

He made visits back to the Orkneys in 1880 and 1891 and retired to Ardrossan, Scotland after 1902 and died on 7 February 1912 and is buried at Dunblane, Perthshire where he died of pneumonia after an operation.

References

E.E. Burke. The search for William Hartley’s grave. Rhodesiana Publication No 8, 1963

R.S. Churchill. Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa. Books of Rhodesia Volume 7, Bulawayo 1969

W.B. Lord and T. Baines. Shifts and Expedients of Camp Life Travel and Exploration. Horace Cox, London 1871

F. Oates (Edited by C.G. Oates) Matabele Land and the Victoria Falls, A Naturalist’s Wanderings in the interior of South Africa. Kegan Paul, Trench and Co, London 1889

J.G. Orford. A Street called Boom – some glimpses of Pioneer Klerksdorp. Dspace.nwu.ac.za > bitstream No_2(1977)_Orford_JG

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd Cape Town 1966

H.L. Tangye. In New South Africa – Travels in the Transvaal and Rhodesia. Horace Cox, London 1896

J.P.R. Wallis. The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask 1865-1870. Chatto & Windus, London 1954

Website: https://ruralexploration.co.za/index.html

Website: https://eensgesind.com/thomas-leask/

[i] The Southern African Diaries, Pvii

[ii] Ibid Pxxxviii

[iii] Ibid PLiv

[iv] Ibid Pxiv

[v] A salted horse has had sleeping sickness (nagana) transmitted by tsetse-fly and survived. After its recovery an affected horse has some immunity and can travel in infected areas and hence was more valuable.

[vi] Wilkinson was nicknamed ‘Cap’ because he had the rank of Captain in a colonial regiment.

[vii] William ‘Old Bill’ Finaughty (1843-1917) in his career killed about 500 elephants who wrote The Recollections of an Elephant Hunter.

[viii] The four bore black powder muzzle-loader (Afrikaans; Roer) was considered the ideal elephant gun in the nineteenth century. The bore diameter is sufficient to fire a lead ball weighing one-quarter of a pound.

[ix] Probably a leopard skin.

[x] Wankie is a Makalaka chief living on the north bank of the Zambesi river below the confluence with the Matetsi river and about three days walking downstream from Victoria Falls. Hwange the town is named after him but is on the coalfield, not the river.

[xi] Van den Berg himself died of fever the next year.

[xii] The Southern African Diaries, P141

[xiii] Ibid, Pxxxvi

[xiv] Millet or sorghum?

[xv] The Southern African Diaries, P190

[xvi] Two other entries say Will Hartley died at midday.

[xvii] I think this must refer to the Sebakwe poort, now a property of the National Trust of Zimbabwe. However the Que Que only joins the Sebakwe river after the poort; so perhaps Leask has confused the Que Que with the Bembezana which does join the Sebakwe before the poort.

[xviii] James Gifford went to the diamond fields and was still there in 1972

[xix] Info courtesy of https://eensgesind.com/thomas-leask/

[xx] General Cronje surrendered to Lord Roberts at Paardeberg during the second Anglo Boer War.

[xxi] Info courtesy of https://ruralexploration.co.za/Klerksdorp.html

[xxii] In the same year 1888 Lobengula would grant the Wood-Chapman-Francis Tati concession the right to mine between the Shashi and Macloutsie rivers [See the article the Wood-Chapman-Francis syndicate of concession seekers under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

[xxiii] A Street called Boom, P2

[xxiv] Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa, P56-7

[xxv] A Street called Boom, P3