Home >

Mashonaland Central >

The June 1896 Mazoe Patrol skirmish with detailed accounts from those besieged and their Mashona attackers

The June 1896 Mazoe Patrol skirmish with detailed accounts from those besieged and their Mashona attackers

How to get here:

Too many political sensitivities to visit currently

GPS Locations

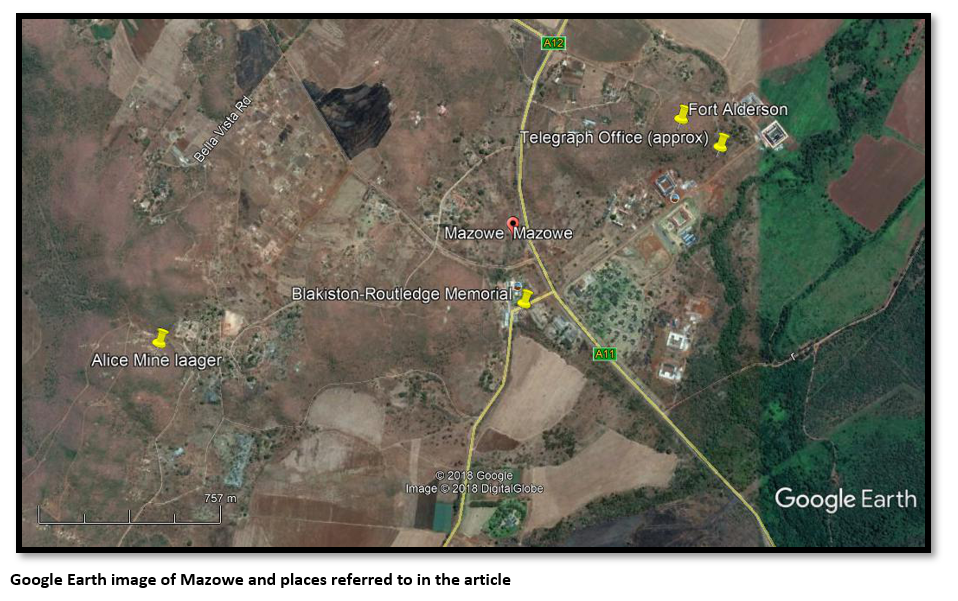

Alice Mine laager 17°30´44"S 30°57´33"E

Fort Mazoe 17°31´27"S 30°58´03"E

Blakiston-Routledge Memorial 17°30´38"S 30°58´30"E

Fort Alderson 17°30´10"S 30°58´55"E

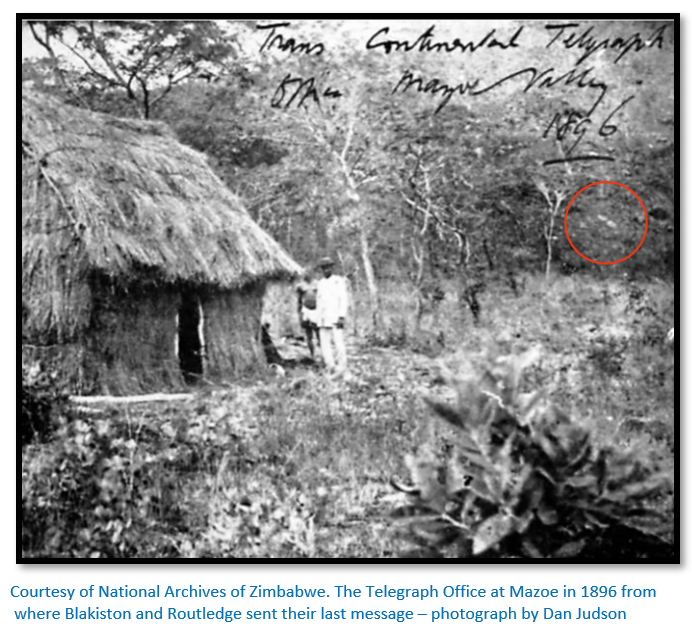

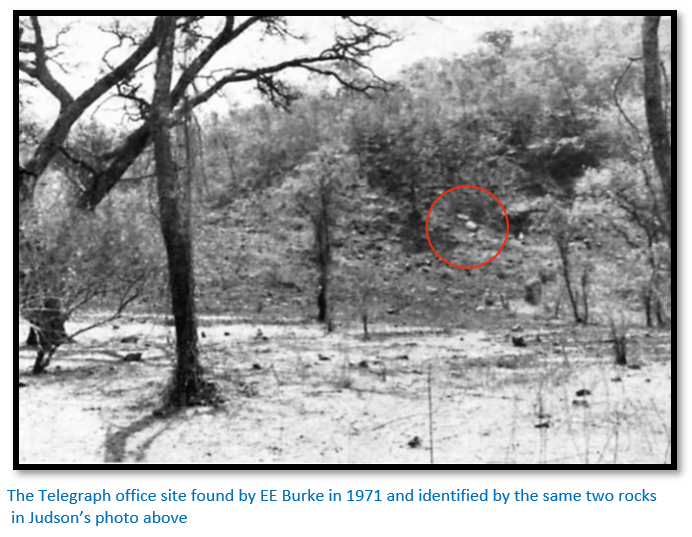

Telegraph Office 17°30´14"S 30°59´02"E

There are numerous accounts of this event which Hugh Marshall Hole in Old Rhodesian Days considers one of the most brilliant rescue exploits of the Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga. It certainly ranks for courage alongside the siege of the Abercorn store at Shamva and the siege of Fort Hill at Hartley Hill [both sieges are described on www.zimfieldguide.com] I have combined the reports from a number of the individuals (James Darling, Hugh Pollett, Hugo Zimmerman who changed his surname to Rawson, John Salthouse) who played key roles to provide differing descriptions of how they managed to extricate themselves from a very dangerous situation when faced by determined attackers estimated by Nesbitt to number fifteen hundred with many armed with modern rifles.

The most comprehensive and definitive source on the subject which was used extensively in some of the articles referenced below is False Dawn by Hylda Richards which is based on the diaries of Dan Judson and his wife Maynie. In 1896 Dan Judson was Inspector of Telegraphs in Mashonaland; on many occasions the telegraph lines were cut and it was dangerous work going out to repair and restore them. Hylda Richards, the authoress, and her husband Tom owned Tavydale farm in the Mazoe valley [the modern spelling is Mazowe] and the route covered by the Mazoe Patrol along the Tatagura was very familiar to her. It was her idea to publish the diaries and she collaborated with Dan and Maynie’s daughter, Mazoe, after their deaths. The life of the Judson’s son Pat, one of the earliest pilots, is covered in another article referenced below.

Randolph Nesbitt was awarded the Victoria Cross, as he was the only professional soldier, being an Inspector in the Mashonaland Mounted Police (before the Mashonaland and Matabeleland forces united to form the British South Africa Police) with the equivalent rank of Captain; civilians were only eligible for the George Cross from 1940.

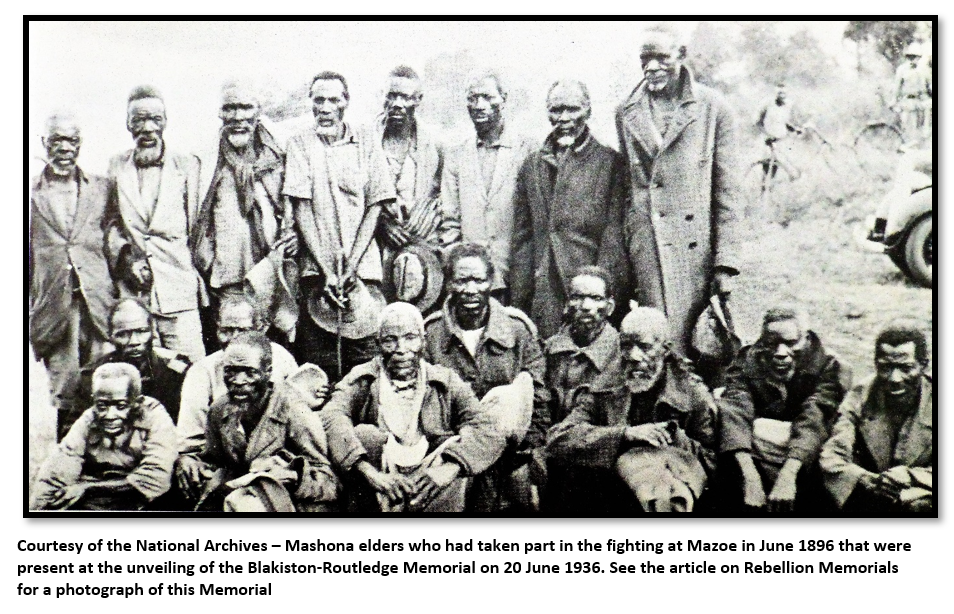

The Mashona version of events is covered in the oral history as told by Sgt Sanhokwe of Mhasvi in E.E. Burke’s article in Rhodesiana.

Background

J.W. Salthouse the manager of the Alice Mine wrote this brief introduction in his report to Judge Vintcent: “The Alice Mine is situated in the Mazoe district, about 27 miles from the township of Salisbury [now Harare] It lies to the west and beyond the end of a long valley, eight miles in length and 500 yards wide at the base, formed by rocky hills heavily timbered on the west and the Iron Mask Mountains on the east. The road to Salisbury runs along the west side of the valley, and on both sides is completely closed in by long, coarse grass and reeds about nine feet high. At intervals it is intercepted by dongas or deep gullies. The Tatagora River [spelt Tatagura by Hylda Richards and in this article] runs parallel to the road, along the middle of the valley. In the neighbourhood of the Alice Mine are the following offices: Mining Commissioner's Office, Telegraph Office, Native Commissioner's Office and two stores. The Telegraph Office is situated at the foot of a small kopje on the Mazoe River, about two miles north-east of the Mine, and is hidden from view.”

The road to Mazoe went through Avondale and east of Mount Hampden and then down the valley of the Tatagura River to its junction with the Mazoe River. The Salvation Army farm was at the head of the valley, now the Pearson Settlement and Mazowe High School. The Tatagura River runs alongside the original road and joins the Mazoe River as it leaves the steep narrow pass, or Poort, of the Iron Mask Range. Below the dam wall of the Mazoe dam and quite close to the confluence of the two rivers was the telegraph hut.

The modern tar road to Mazoe via the Golden Stairs was in 1896 just a track and too steep for ox-wagons.

The first gold Mine to be pegged in the Mazoe valley was the Jumbo Mine, named after a famous elephant of that name at London Zoo. The Alice Mine was pegged two weeks later and is named after a song of the music-halls that was popular at the time. A mate was found for Jumbo called Alice, but Jumbo was bought by Barnum’s Circus and taken to America and so the song went:

Jumbo said to Alice,

‘I love you!’

Alice said to Jumbo

‘I don’t believe you do

For if you only loved me

As you say you do,

You wouldn’t go to America

And leave me at the Zoo!’

Rothschild’s Syndicate had pegged the Alice; the Johannesburg Mashonaland Exploration Syndicate owned the Vesuvius, Etna and Stromboli, but the Vesuvius had just been sold to Goldfields of Mazoe and several of the men Fairbairn, Faull, Stoddard and Pascoe, who were resident at the time were erecting a ten-stamp mill at the Mine. The chronological order of events is as follows:

Monday 30 March 1896

James Dickenson, the Mining Commissioner and JP at Mazoe wrote to Judge Vintcent, the Acting Administrator of Mashonaland saying: “The latest news here [re the uprising] seems rather serious. Would it be too much to ask that we here in Mazoe be notified by wire when anything startling occurs? It would appease our anxiety.”

Tuesday 14 April 1896

In the Government Gazette of the above date, Judge Vintcent issued a warning ‘Note to Prospectors and Others’ in which he said he had: “no reason to believe that there is any probability of a similar rising of natives in Mashonaland” and continued with the advice that there should be vigilance in case advantage was taken of the crisis to attack and loot isolated stores, mining camps and farms. Those who lived in such places were told that because the area was very extensive there might be difficulties of: “speedily affording relief” if certain emergencies arose. Therefore, they were asked to report any suspicious circumstances to the nearest BSA Company official, and all possible steps should be taken by them personally: “to place themselves in a position of defence and security.”

However, it is extremely likely that the persons to whom this note was issued never read or had their notice drawn to this Government Gazette.

Friday 24 April 1896

A petition, signed by fourteen Mazoe residents, was sent to the British South Africa Company (BSA Co) requesting ammunition. All had rifles, but limited ammunition, and one thousand rounds was sent with instructions that they were for “judicious use” only. An anonymous article in the Rhodesia Herald mentioned theft and looting in the Mazoe district; since the Police had withdrawn, their camp had been vandalised and other camps had been robbed.

Sunday 31 May 1896

News comes into Salisbury that a miner named Dougherty has been killed on his Lomagundi claims and his body thrown down a shaft.

Tuesday 16 June 1896

Dan Judson sent Salthouse a telegram stating that men had been killed the previous day at the Beatrice Mine [Tate the Mine engineer, Koefoed a prospector and four mine workers] with other killings suspected in the vicinity of Salisbury.

Wednesday 17 June 1896

As news of the Norton family and other victims including a prospector named Stunt at Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal trickled into Salisbury (now Harare) the residents at Mazoe were warned by again by telegraph of the danger. Prospectors, miners, farmers and storekeepers were particularly vulnerable and many stores and houses were looted and burned. Salthouse replied that he would gather in the nine men and three women in the area and requested a wagonette be sent out to take the women. While waiting for a reply Salthouse advised all the residents to come to the Alice Mine.

James ffolliot Darling was camped at the Etna Mine and wrote to his father: “On June 17 I went over to put up boards on my mining claims and got back rather tired just about 3 o’clock. I had just taken a bite of food when a note arrived from a man named Fairbairn to say that the natives were committing outrages against the whites under the instigation of the Matabele. He stated further that the whites in our neighbourhood were going to the Alice Mine for defence. I was undecided whether to go or not, as I thought it probably a false alarm, but on learning from two men near me that Dickenson and Cass had gone to fetch their wives, I concluded that the affair must be serious and made up my mind to go.

Accordingly, I went around to the Alice Mine and found Mr Salthouse making a rough laager on a small kopje behind the camp. The position, though the best in the immediate neighbourhood of the camp, was quite unsuitable for the purpose, being commanded by hills on three sides from which shot could be fire at a distance of from 400 yards to 700 yards.”

As they waited for people to come in, Fairbairn and his workers from the Alice Mine strengthened the laager and closed in the top with timber and rocks, the idea being that once the three women were safe in Salisbury, the men could stay here if necessary.

That night, as there were no signs of unrest in the Mazoe valley, the men did not go into the laager, but took turns to keep a guard around the house and the Alice Mine. Nothing happened and Darling wrote the men thought it would be better to go into Salisbury than stay at the Mine, but they would wait until they had news from Salisbury.

Those now assembled at the Alice Mine are listed below in the schedule as resident at Mazoe. The Native Commissioner, Henry Hawken Pollard, was on patrol north of Mazoe at Tamaringa’s Kraal where he was killed by his own policemen. Pollard had thrashed Chief Chiweshe for failing to report cases of rinderpest amongst the cattle and this created much resentment amongst the Mashona. Eye witnesses say that it was the spirit medium Nehanda who pronounced the death sentence on Pollard.

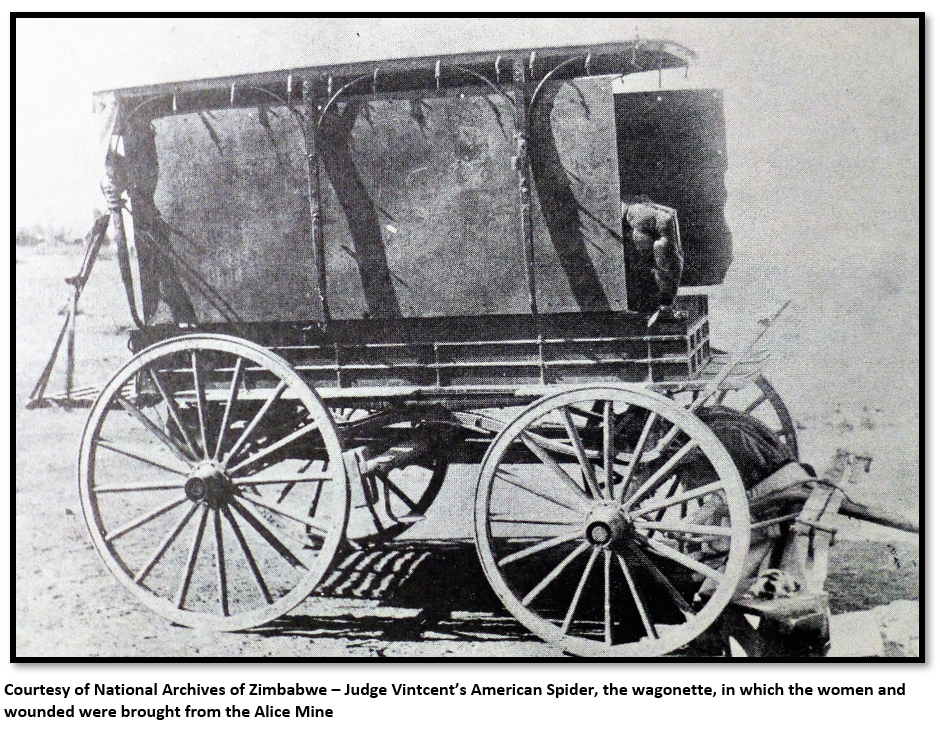

Acting Administrator Judge Vincent arranged for his own American spider (a four-wheeled wagonette with open sides and roof drawn by six mules – called at times a wagonette, wagon, coach, van and ambulance) and driver, Hendrick, and two volunteers, Blakiston and Zimmerman (who later changed his surname to Rawson) to leave for Mazoe at midnight. Dan Judson had intended to take the wagonette, but Blakiston, one of his telegraph staff, begged to go, as he said he had no excitement since coming into the country earlier in the year and Judson gave way.

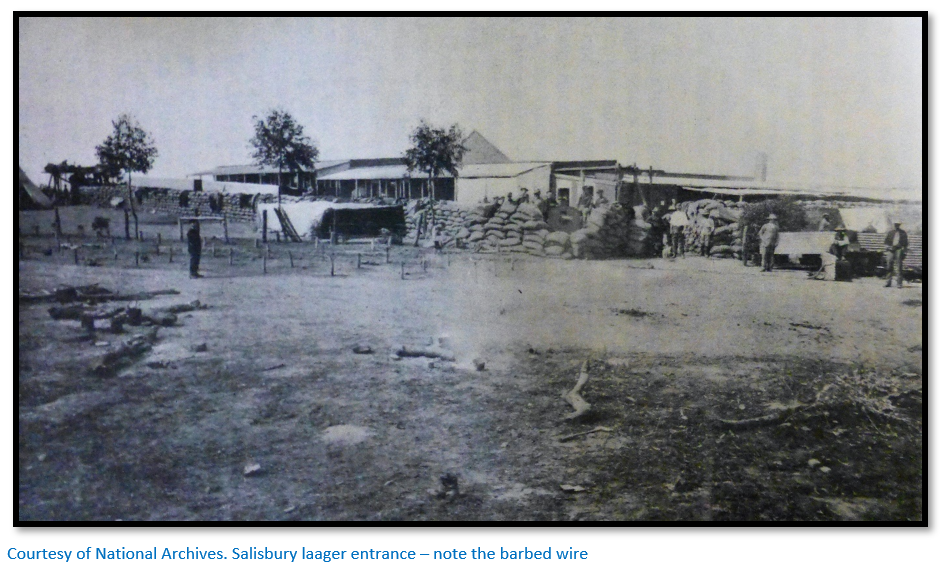

One hundred and forty men of the Rhodesia Horse Volunteers had left Salisbury on 12 April 1896 under Captain (later Col.) Beal to help their fellow citizens nearly five hundred kilometres away in Bulawayo, so Judge Vintcent could only muster the remaining two hundred and fifty men, with eighty Martini-Henry rifles and one Maxim gun between them to protect about three hundred women and children in Salisbury. Reinforcements were available from Mafeking in the form of Imperial Forces, but transport difficulties complicated the problem; one hundred and fifty of the two hundred oxen were lost enroute to rinderpest.

Rawson writes: “As I was closing the store that evening Blakiston, of the Salisbury telegraph staff, came and told me that the Acting Administrator, Judge Vincent, had asked him if he would go out to Mazoe with an ambulance to fetch the women from the Alice Mine. He asked me to go with him, and I said I would. At the Judge's house at 9 p.m., I was given a Martini rifle and fifty rounds of ammunition. I had previously borrowed a revolver...in pitch darkness we drove along the Mazoe road.

We had not gone more than fifteen miles when we thought we saw a white farmhouse to the right of the road; we stopped the ambulance and both got out to investigate, only to find it was a big white rock. On getting back into the ambulance, I got in first and held out my hand to help Blakiston. He lifted up his rifle, and in putting it in my hand he slipped my finger through the trigger-guard, and as it was at full cock the weight of the rifle let off the bullet, which went unpleasantly near his head.”

The three men travelled by night on Wednesday 17 June 1896 and reached the Alice Mine at sunrise. They found a small group of twelve men, three wives, twelve loyal Mashona employees and George gathered at the Mine where a rough laager had been built of rocks and timber. There was much discussion concerning over whether they should move to a local trading store, or stay at their laager, return to Salisbury, or stick it out at Mazoe, if they should collect the women and leave the men, or return as one party. Rawson again: “We journeyed on, finally arriving at the Alice Mine at sunrise. What a glorious breakfast Mrs. Salthouse gave us on arrival. I can remember now how we did justice to it - ham and eggs and a tin of sardines each to finish up with. We little thought that it was the last meal we were to get till we got back to Salisbury three days later. After breakfast Blakiston walked over to the telegraph office which was about one and a half miles away, to report to Salisbury, and I was able to take stock of the situation. Mr. Salthouse, the Manager of the Mine, had heard on the previous day from Salisbury about the murders, and had collected all the neighbours that he possibly could at the Mine; they had been on sentry duty all night but had not been molested. It was agreed that we should water and feed the mules and all leave for Salisbury at noon.”

Thursday 18 June 1896

On this day a mass meeting was held at the Market Hall to meet representatives of the BSA Co. to provide for the safety of the town’s inhabitants with a Defence Committee being set up and a requirement for every man to do picket duty on roster. A second patrol of five men was sent to the Mtoko district to warn Native Commissioner Ruping but was unable to make it and took refuge with the Jesuit Father’s at Chishawasha; Henry Ruping was killed by his native police about 24 June 1896 at Mrewa.

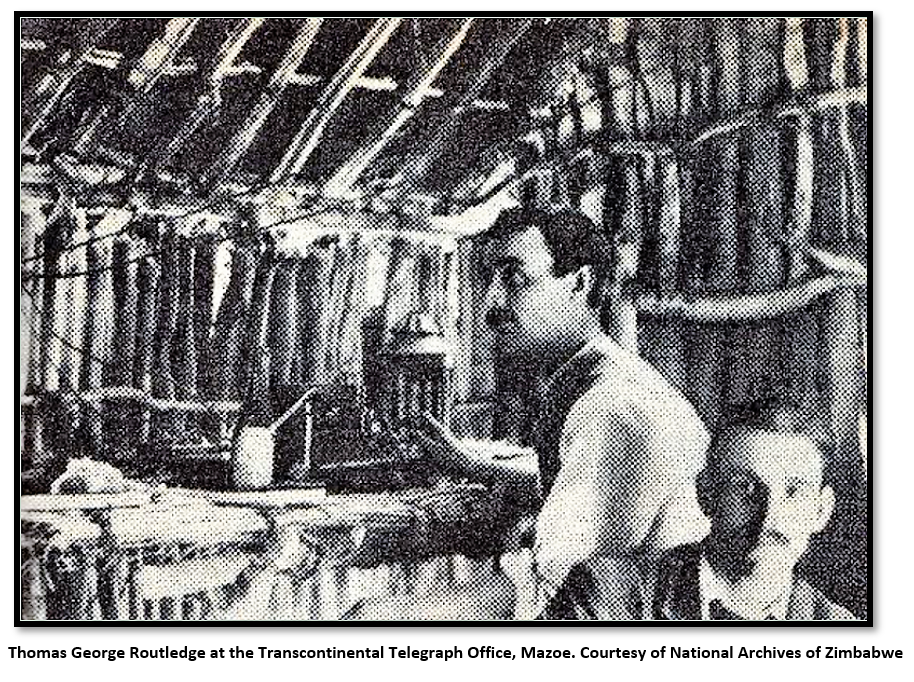

Blakiston reported his safe arrival by telegraph to Judson: “18 June 1896. Arrived safely, starting back at 11 with three ladies, Salthouse riding…the whites at Mazoe are unanimous in risking coming in to camp…intend leaving this morning unless authorities can assist.” Leaving Routledge at the telegraph, Blakiston, Zimmerman (later Rawson) and Darling walked back to the Alice.

Soon after Routledge sent a telegraph messenger to say that Judson wished to communicate with Salthouse at once. Salthouse went down to the telegraph office on his black pony, the only horse available, and on the line from Salisbury, Judson told him the rising was now general and advised him to laager at the Alice Mine, rather than attempt the journey back to Salisbury. Salthouse replied that six men had already set off and there was insufficient left to guard the women. Judson suggested the waggonette leave immediately and catch up with the donkey cart as they would have a better chance of getting through together.

Six of the European men (the four putting up the mill including Fairbairn, Faull, Pascoe and Stoddart, together with Cass and Dickenson) and their Mashona carriers had set off in the late morning with a donkey cart, to clear the road for the much faster wagonette and six mules following behind.

Salthouse galloped back and despite a certain amount of dissension and argument managed to persuade them all to proceed to Salisbury. The women (Mesdames Cass, Dickenson and Salthouse) and Burton, who was suffering from fever, went into the wagonette with Hendricks driving and Zimmerman (later Rawson) beside him, with Blakiston, Darling and Spreckley following on foot. Salthouse rode down to the Telegraph Office and wired Judson through Blakiston, saying: “June 18. (Mazoe?) people intend to (come to?) Salisbury (in the wagonette?) they are (leaving?) as soon as possible.”

The six men with fourteen carriers and the donkey cart continued on their way. Darling wrote: “It appears that Pascoe got on safely until he passed my camp [at the Etna Mine about five kilometres from the Alice] Just there, as Dickenson and Cass were going along quite unsuspiciously, they were killed by natives lying in ambush alongside the road. Pascoe’s attention having been attracted, he looked back and saw some natives hacking at something on the road, so he sent back one of his carriers to see what was going on. The latter quickly returned saying that the two white men had been killed, so Pascoe dodged off to one side and walked back through the timber.”

Fairbairn reported that he and his two companions were in the cart when they saw some natives ahead striking something on the ground with their knobkerries and that Pascoe’s carrier reported: “Fundissa is firri.” That is, teacher [Cass] is dead. This account is not possible as they were separated by the ambush. Once the ambush had been initiated the carriers flung down their loads and fled into the bush.

Faull, Fairbairn and Stoddard turned around the donkey cart and were joined by Pascoe who had dodged off the road into the trees emerging further on to join the cart and get up with Faull. Fairbairn states: “we had only returned about a hundred yards when Faull, who was driving, was shot through the body by a native concealed in the long grass about four yards off. I shot the native, and at the same time one of the donkeys was shot. The wounded animal ran for about a mile and then fell dead.”

When the donkey dropped, Pascoe, Fairbairn and Stoddard left the cart with Faull’s dead body in it and ran for the laager, turning and firing at their attackers who were following behind. When they were over a kilometre from the Alice Mine, Fairbairn writes they met the waggonette: “with the three ladies and the rest of the party from the Alice except Mr Salthouse who had gone to the telegraph office [and Routledge the telegraph operator] Shouting out what had happened, they helped to turn the wagonette and breathlessly they all clambered on to it, with Pascoe on the roof.”

Zimmerman (later Rawson) in the wagonette wrote: “We left the Mine at noon, several of the men walking and the ladies in the ambulance; Salthouse was on his black pony, the only horse we had. We had only gone about five miles when, just as we were approaching a deep donga overhung by large trees, a terrible fusillade was poured into the men walking in front and Dickenson, Cass and Faull were shot dead. The ambulance was quickly turned around but in doing so it was upset and the women pitched out. It did not take more than a few seconds to right it and we set off back to the Mine as hard as we could go; we were being shot at all the time from the long grass but fortunately nobody was hit.”

Fairbairn continued: “We had not proceeded about two hundred yards, when about fifty natives came out of the grass in our rear. We opened fire through the back window and from each side of the wagonette and kept the rebels in check…If the wagonette had proceeded one hundred yards further, it would have reached a very bad donga where it would have been impossible to turn and no doubt, we should all have been murdered.”

Darling, with Blakiston and Spreckley, were following behind and: “proceeded towards my camp [Darling’s] intending to have lunch there. Just before we got to the bend of the road where the Alice Mine branches off, we heard a few shots, and presently the mules came around the corner at full speed with Pascoe on top (of the wagonette) and Stoddart sitting behind almost done up.”

The three men raced after the wagonette: “It was as much as I could do to keep up until we got to the Alice camp. We saw the enemy turning the corner as we hurried the women into the makeshift laager. Two of them who had started off so jolly an hour before were now widows.” [Mrs Ada Cass and Mrs Jane Dickenson]

Their attackers, not wishing to come closer, ran to the store on the left of the laager: “But a few shots at one thousand yards made them change their minds and take refuge in the bush on the right.”

Darling gave Mrs Cass his shotgun: “the only spare gun they had left as all the others had been lost with the murdered men. I told her that if the enemy made a rush, she was to fire at them in the face. She said she would, but after a while she brought the gun back saying she couldn’t.”

Their attackers now began approaching: “Pascoe and I got on the highest rocks and then he said: ‘Fire a couple of shots to alarm Salthouse at the telegraph office.’” Nobody had thought of sending a message to Routledge for further help from Salisbury, so Hendricks the driver was offered £5 to take a message down; “and there being nobody between us at the moment, he started off straight away.”

Salthouse was at the telegraph office waiting for a reply from Judson which when it arrived: “asked me to secure the telegraph office and papers as far as possible, and also send a wire to be forwarded to Major Forbes, on the African transcontinental Telegraph Company’s line.” Routledge and Salthouse then returned towards the laager meeting Hendricks on the way who was bringing the laager’s note which said: “Come at once, we are surrounded by Matabele. Wire Salisbury for relief.” The three men hurried onto the laager under fire from the nearby kopjes.

Routledge, who could not ride, ran using the stirrup of Salthouse’s pony, before Salthouse stopped at the mine house to collect ammunition and water, leaving Routledge to arrive at the laager alone. Darling at once asked Routledge if he had sent the message to Salisbury requesting help. When he said no; they said he must take Salthouse’s pony and return to the telegraph office to send the message.

Routledge: “said he could not ride and would not go without an escort. We told him it was ridiculous to take an escort when there were only seven men to look after the women, and if he hurried, he could get along alright, as there were still no natives on that side. After some delay, Blakiston said to Routledge, ‘Will you go if I go with you?’ He said he would.” Salthouse reluctantly gave up his pony.

Blakiston was a telegraph mechanic, but not an operator; Routledge was a telegraphist.

Death of Blakiston and Routledge

When they reached the telegraph hut, Routledge sent a message through to Salisbury. The exact message has not survived and has been variously quoted as: “We are surrounded. Dickenson, Cass, Faull killed. For God’s sake…” and “We are surrounded, send us help, this is our only chance. Goodbye.”

Hugh Pollett says:” Two minutes after sending this, both men and horse lay dead about half way between the telegraph office and the laager.”

Dr Howland speculates that Blakiston stood in the doorway of the telegraph hut and gave a warning as he saw the Mashona running across their line of retreat. Off they set, Routledge in the saddle and Blakiston at the stirrup. Bullets whistled around them, but they managed to cover half their return journey, eventually coming into view of those watching from the laager.

Darling’s letter to his father continues: “I was guarding on my right and was too busy to look around when Mrs Cass said, ‘here they come from the telegraph office, one on horseback and one on foot.’ In the meantime, some Mashona had gone over to the store which lay in the path of the telegraph office and presently Mrs Cass said, ‘Oh, they are firing on them – the horse is shot – he is down – no, he’s not, he’s up again – the man is shot, they’re down – no, the man is up, he’s running, he’s running hard. Oh, he’s down, he’s dead’ [Blakiston] All this time I could not turn my head but was firing away on my right. I asked about the other man. ‘He’s running towards the bush’ she replied, ‘and they’re firing at him.’ He disappeared and some more shots were fired, and we knew that he was killed. [Routledge] We were awfully sorry for them, especially Blakiston who had willing risked his life to save the rest of us.”

Defence of Routledge

Darling implies that Routledge’s conduct is less brave than Blakiston because he initially refused to go back to the telegraph office. This less than positive view of Routledge in Darling’s letter is unjust and Hylda Richards corrects the image in her book False Dawn. When he was asked to go back to the Telegraph office he had just returned through a fierce fusillade of fire back to the Alice Mine fort: “With the enemy covering the road between the laager and the telegraph office and likely to cut it off at any moment, Routledge had been expected to walk the one and a half miles, the last part of which was thick bush, re-open the office which he had closed down, re-assemble the instrument which he had dismantled and then attempt to contact Salisbury who would not be expecting any more calls from Mazoe – all of this, with no one to keep watch while he made the attempt. He would then have to walk back again. Because he initially refused to do this, Darling has suggested he was a coward.”

Judson, Salthouse and Rawson disputed Darling’s interpretation. Indeed, Salthouse reported: “Blakiston and Routledge then left for the telegraph office to wire to Salisbury for relief, although it seemed almost sure death to the poor fellows.”

Rawson wrote: “I do not think Salthouse would have allowed them to go if it had not been for the three women with us. Salthouse gave them his horse and we watched them go down the kopje and round the far bed, Blakiston riding and Routledge at his stirrup. We waited anxiously for about an hour, and then we saw them coming around the corner and at the same time heard firing. Salthouse, who was looking through his glasses, said that Routledge was now on the horse and Blakiston on foot.” Routledge had been wounded in the foot.

Routledge, on the day of his death, had been excited because he was about to go on leave to join his wife and two children, the younger of whom he had not seen. Their bodies lay for months in the veld until a relief column entered the valley. Lieut. Harbord, a member of Nesbitt’s Patrol, spent time in the laager and wrote: “the body of the telegraph clerk, who had been shot when he left the laager a day or two before to wire to Salisbury, was lying in the open about four hundred yards below. It seemed horrible to leave the body lying there, but the firing was so hot that no one could go down and bring him in.”

The siege continues

Salthouse wrote that there were many miraculous escapes and there were good shots amongst their attackers: “One [Mhasvi] we specially noticed had taken up his position behind a rock about five hundred yards above us and was using his rifle with great skill and judgement. From his shouts and directions to the others we concluded that he was a Matabele.”

Darling had a duel with this attacker: “At first, they advanced quite confidently, but we soon put a stop to that; the first man shot I bowled over, as he was running across an open glade, at 600 yards. Three or four ran out to carry him in; then I let rip at them and another fell, probably from fright. I fired another shot, and he dropped again. In fact, it was very hard to tell when we had killed one of them, for they dropped into the long grass whenever a bullet passed close to them ... Before this, a Matabele had found a nice rock on the hill about 500 yards from us and had opened fire from it. We could see only his head when he was shooting, and sometimes not even that. I got off my rock and stood behind another which covered me from him but left me unprotected in front. I suddenly felt a bang on the elbow and looking down I noticed that my arm was bloody and my shirt torn. I thought, “I can’t be shot in the elbow or it would have hurt a great deal more,” and then I saw what had happened; the bullet had struck the rock about a foot off, and splinters from the rock and the lead had hit me. I got a nasty gash, and it became a bit stiff and sore, but it was better the next day.

As we seemed to be in an exposed corner, I told the three women to get farther down under the rock. They behaved very well, and kept our bandoliers filled with cartridges as we required them. After a bit, a big bullet came whizzing through, touched the rock, and grazed us all. Soon afterward, another hit a branch just in front of me. They had me marked, as my hat was rather light in colour and easy to see. Later, I put some blue cloth over it, and then it was not so noticeable. There were seven of us firing, and we were put to the pin of our collar to put the beasts away. Pascoe was doing good work on the rock close by me, and Salthouse, Fairburn, Zimmerman, Stoddart, Burton and Spreckley were all firing from the other sides of the laager.

As the afternoon wore away, three natives got into a thick patch of bush and long grass within 100 yards of our position, and one of them crept into a hut near us. As a rule, we could fire only at the puffs of white smoke. One fellow who had a Lee-Metford rifle smashed the rock just at my front in line with my face and knocked splinters over me. We dropped a few of them, but it was hard to say how many. As night came on, the fire slackened and finally died out, with the exception of the occasional shot. After dark we induced a Cape boy of Salthouse’s to go down and set fire to the hut the native had been firing from. The boy brought back with him some biscuits and water.”

The number of men within the Alice Mine fort had been reduced from twelve to seven and the situation was now dangerous and nobody knew if the telegraph message had been sent. They were fired upon all afternoon, the attackers getting within one hundred and fifty yards and into a nearby hut. Darling wrote: “Darkness came on and the firing abated a little. George, Salthouse’s Coloured man, then went down and set fire to the hut from which the native had been firing…that night was like one long nightmare. I sat on top of the only entrance to the laager and stared down until I thought the eyes would drop out of my head. I could scarcely keep them open, being terribly sleepy after the previous night’s vigil and the day’s anxieties.”

They expected a dawn rush, as two native policemen who had visited the laager had deserted and their attackers would now be aware of how few defenders there were in the laager. Darling continues: “I could hear them talking in the bush under me and moving about; and every sound and shadow was magnified by my excited nerves into savages approaching. They were confident they had us in a trap. After they had their grub, their general shouted out of the bush about eight hundred yards away where his camp was situated, ordering detachments to watch all roads around us so that we could not escape during the night. Several times he came out and roared one order or another across the valley to men stationed on the other side. One sentry behind a rock close above us stayed there all night, where he had a fire and something to eat. He called out once asking indignantly why they, the Mashonas, had left him, a Matabele, without tobacco, and ordered them to send him some up at once.”

Just before dawn, George set fire to another hut which had been used for cover and managed to bring back some biscuits and water from the house. The defenders were pleased to see daylight and they found the firing slackened off at sunrise. The store was robbed, but the attack slackened off, the reason being that the Mashona had left to ambush the expected relief party.

Dan Judson’s Patrol

Salisbury had received a telegraph message from Blakiston and Routledge saying: “Blakiston to Inspector Judson. Three men killed, Alice Mine surrounded, send help at once, our only chance, goodbye.” Judge Vintcent allowed a second rescue party comprising Lieutenant Dan Judson, chief inspector of the BSAC Telegraph Department and four troopers of the Rhodesia Horse to leave just before sunset on Thursday 18 June 1896. At Avondale they were joined by Paymaster Captain Stamford Brown and at Mount Hampden they were joined by three more troopers in the early morning. As dawn broke they found they found to their dismay they had missed the road to Mazoe and were near Tavydale farm [By coincidence this is where Hylda Richards, the author of False Dawn lived with her husband and family many years later] Tprs Finch, King, Guyon and Mullaney whose horses were fatigued returned to Salisbury, the remaining seven (D. Judson, S. Brown, W. Carton-Coward, C. Hendrikz, W.S. Honey, E. Niebuhr and H. Pollett) regained the Tatagura road and rested for two hours at the Cass homestead at the Salvation Army farm [then Pearson settlement and now Mazowe High School] before descending about midday into the Tatagura valley.

Dan Judson’s report to Judge Vintcent stated: “At noon we moved on, and I warned the men of the gravity of the situation and issued instructions to be observed in the event of attack by a superior force. About a mile down the Mazoe Valley we entered a stretch of thick, high grass, terminating in a dense clump. I gave order to gallop, and we went forward in the following order: Myself first, Capt. Brown, Tprs. Hendrikz, Niebuhr, Pollett, Honey and Carlton-Coward, riding in single file.”

Hugh Pollett wrote: ”one could not but be struck by the strange quietness pervading everywhere…I have journeyed down this valley a good many times, but never without seeing the natives at work in their mealie fields or other abundant signs of life around me…The sun was blazing hot in the valley, the wind gently rustling in the grass and all seemed wrapped up in peace and quietness…It hardly seemed possible that any moment we might be brought face to face with an enemy and fighting for our lives.”

Judson continues: “As Niebuhr and Pollet passed the end clump a volley was fired at us. I wheeled my horse round and saw Niebuhr's and Pollett's horses fall, and the riders on the ground. I was only 30 yards off, and, getting a good view of the enemy, fired two charges of slugs into the middle of them [Judson was using a double-barrelled shotgun] and placed two of them "hors de combat," and, I believe, thus prevented them from firing on Honey and Coward, who were then passing the bush. Coward was thrown from his horse, but quickly remounted. Brown and Hendrikz engaged the enemy, whilst I got Niebuhr, who was badly wounded in the hand, up behind me. Pollett clambered up behind Hendrikz, and we all fired a volley into the enemy and galloped off without further casualty.”

Pollett wrote that his horse gave a terrible plunge and came down on its head: “pitching me a good ten yards…I still retained my rifle, having taken it with me out of the gun-bucket in my fall. I tried three times to get up, but for the moment I was unable to do so as all the breath had been knocked out of my body. At last, regaining my feet, I saw Niebuhr lying on the road bleeding profusely. Both horses were killed outright.”

Pollet got up behind Hendrikz; Judson managed to get Niebuhr, whose arm and hand were wounded, up on his horse behind him. Pollett writes: “In the meantime the rest of our party had not been idle and three of the enemy lay dead in the bush, Judson, who had a double-barrelled gun loaded with buck shot accounting for two of them. We had now no time to waste as the natives in front attracted by the firing were coming down from the hills trying to stop our advance, so after helping Niebuhr, who had been shot through the hand, on to Judson's horse and getting myself up behind Trooper Hendrikz we pushed on as quickly as possible. We still had six miles to go and firing was opened at us now from both sides.”

Judson continues: “We did the next seven miles without mishap, keeping up a running fight, dislodging the enemy from the thick clumps of grass by firing volleys into them as we advanced and then rushing the dangerous spots. Seeing a wrecked cart with a dead white man [Faull] and wounded donkeys Iying near the roadside, I believed it possible that all the Mazoe inhabitants had been murdered and decided that if we saw no signs of them our only course was to reach the telegraph office, inform you of our situation, and then take up a position on one of the kopjes.”

Judson’s party who were: “keeping up a running fight, dislodging the enemy from the thick clumps of grass, firing volleys into them as we advanced, then rushing the dangerous spots” did not see the bodies of Cass and Dickenson as they were probably on the verge of the road and out of sight. But having seen the body of Faull: “We then believed it possible that all of the Mazoe inhabitants had been murdered and I decided, and so informed my comrades, that if we saw no sign of them our only course of action was to reach the telegraph office, inform Salisbury authorities of the position of affairs and then laager up as best we could.”

He continued: “After proceeding a few hundred yards we discovered a party of the enemy running along the mountain-side about three hundred yards off, their intention evidently being to occupy a position overlooking the road where they could open a deadly fire on us without incurring any risk to themselves. I halted the patrol and opened fire on the enemy and forced them to retire. We then started off again at a gentle canter, keeping up a running desultory fight, dislodging the enemy from their thick clumps of grass by firing volleys into them as we advanced and then rushing the dangerous spots.”

Finally, they turned the sharp corner before the Alice Mine. On the afternoon of Friday 19 June. Salthouse spotted seven men and five horses making for the telegraph office. Looking through his binoculars he saw: “seven men and five horses – they could not see us – who appeared to be making for the telegraph office. We jumped to our feet, men and women joined in one tremendous shout. The shout was heard and we saw our friends, amidst a hail of lead, turn their horses and, while firing volley after volley, gallop for the laager which they reached safely. We assisted their advance as far as possible by maintaining a steady fire against the native, who were in strong force on their left.”

Luckily for Darling and his comrades, the Matabele had been temporarily distracted by the supplies they had looted, including liquor, from the Holton Hotel and store, but before the day was finished, Darling had experienced further close shaves: “I was touched that day, once on my heel and once on my chin; but nobody was hurt and the women kept up splendidly. They had nothing to eat but a biscuit and water the whole time.

At about four in the afternoon the Matabele leader began a great shouting for his troops, but they did not respond with alacrity, as they were busy in the store. After a little while we heard shots in front of us, and a small body of mounted men came into view. The natives were firing on them, and the leader roared again to his warriors at the store to run across and intercept them. Presently I observed some of the rascals running down the hill through a belt of bush about 600 yards away, and I opened fire, planting a few bullets in their midst. Pascoe also fired on them, and between us we quickly sent them back. In the meantime, we heard, to our joy, the rattle of .303 calibre rifles, carried by the relief patrol, and up galloped five horsemen, two of them each carrying a man behind him. They had had an exciting ride out, as they had lost their way once, and had been fired at twice out of the grass at the road-side, having one man wounded and two horses killed.

We were very much disappointed at the size of the party, which was too small to enable us to get out, though, of course, it was a great assistance. After their arrival, the natives warmed up and kept us pretty lively for the rest of the afternoon, just to show us they were not frightened, I suppose ... That night we agreed to sleep in pairs, so that we could keep watch alternately at two-hour intervals. This, of course, was a welcome relief. “

Hugh Pollett says: “At 2 o'clock a stir was visible amongst them all, and the Matabele boy was heard to call out to his followers to rush the laager. The besieged knew this meant one of two things, either it was immediate death to them, or that relief was near. Happily, it turned out to be the latter, as, to use their own words, under terrific fire Lieut. Judson and his men galloped up to the laager.”

Friday 19 June

Rawson takes up the story: “We now hoped for the best, and started to make our defences a little higher, and Salthouse went down to the Mine with our two-coloured drivers [Hendrik and George] and brought up a tin of biscuits, two buckets of water and some dynamite fuse and caps. These explosives turned out to be a perfect godsend. At night, the natives crept up always nearer and nearer, and it was only small dynamite charges with short fuses [five second fuses] thrown out as fast as they could be made which prevented the natives rushing us.” The fort was subjected to a constant sniping fire since daybreak and the trading store in the distance was looted; during the previous night, the defenders had thrown dynamite with short fuses to thwart any attacks.

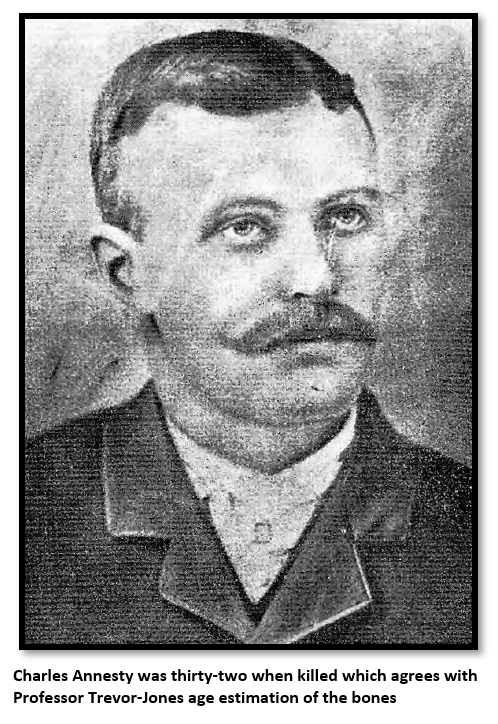

Death of Charles Annesty.

During the night they heard shots in the distance, a dog howling and a donkey bell in the distance. They believed these sounds may have signalled the death of Charles Annesty, a prospector who rode a donkey and had a spaniel dog. Salthouse says: “We heard him being murdered and later saw the two donkeys lying dead.”

Darling who was Annesty’s neighbour at Mazoe reported: “Early in the night (19 June) some shots were heard in the neighbourhood of the hotel and soon afterwards we heard the tinkle of a donkey bell on the flat and a dog howled out there during the night. From information received since I have every reason to suppose that Mr Charles Annesty, who arrived here from British Columbia about twelve months ago, was murdered at that time. He was due back from Chipadzi’s kraal about that time and used to ride a donkey and had a spaniel dog. He would come up that road, as his camp was close to mine, a couple of miles further on from the laager.”

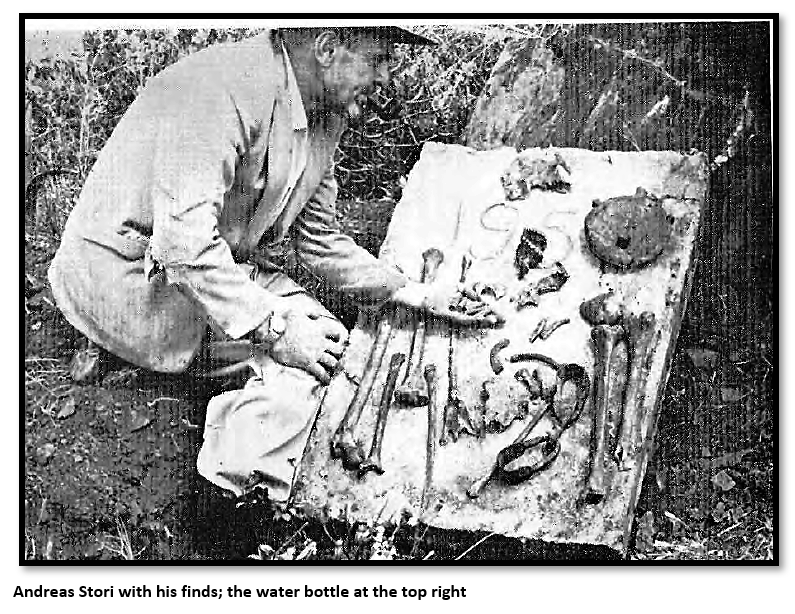

An article by A.S. Hickman – The Death of Charles Annesty appeared in the Rhodesiana Publication No 12 of September 1965. In 1955 the Swiss born Andreas Stori was building a summer house on the summit of the hill near his house overlooking his Mine, Stori’s Golden Shaft, when he came across a rusted military water bottle and five .303 cartridge cases which he kept as interesting items. The position does not overlook the laager site and therefore was not likely to have been occupied by the Mashona besiegers. In 1957 his employers were using a bulldozer to expose gold reef when they came across a human skeleton at the bottom of an old prospecting shaft. Col A.S. Hickman, H. Ward of the Rhodesia Herald, Dr Brain and Mr Guy of the Queen Victoria Museum and Trevor Jones examined the remains and concluded that this was probably Charles Annesty who had returned from Chipadzi’s kraal with his donkey and spaniel dog and was probably attempting to reach the Alice Mine when he was shot.

The water bottle was of military pattern first issued in 1895 and the cartridge cases were all in use in 1896.

The siege continues

Now there were fifteen men in the laager they could get some badly-needed sleep and slept in pairs and took turns with two-hour watches. But food and water and ammunition were getting short, the small party might be stormed by hundreds of attackers at any time and they decided to request further help. The Cape driver, Hendrik, was promised £100 if he delivered a letter to Judge Vintcent. When the moon went down about midnight, he led off a black horse whose hooves were wrapped in rags to muffle their noise, and despite accidently firing his revolver and warning the besiegers, Hendrik managed to get away without knowing that a relief party of thirteen led by BSAP Inspector Randolph Nesbitt had already started out from Salisbury.

The letter written by Dan Judson said:

Very Urgent Alice Mine

Mazoe

H.H. The Administrator

Salisbury Friday June 19, 1896 10pm

Sir, - I beg to inform you that I arrived here about 1:30pm having literally fought our way through the whole of the Mazoe Valley. Lost two horses killed, and Tpr Niebuhr badly wounded and Pollett slightly (both these men’s horses were shot and they consequently rode behind riders on two other horses) In this respect I would mention Tpr Hendrikz who picked Pollett up and carried him nearly five miles. I sent back early in the day Tprs Finch, Guyon, King and Mulvaney with their horses (knocked up) Mr Salthouse, in charge here, reports Blakiston, Routledge, Dickenson, Cass and Faull killed. Since my arrival we have had natives firing on us at a distance varying from two hundred to fifteen hundred yards, and there is no doubt that we are all in a critical position as ammunition is rapidly running out. We have absolutely no shelter for the ladies and they have to crouch behind rocks; provisions also running out. It is imperative that a force of at least forty men, with a Maxim, should come out to our relief at once, as I am afraid that all the Mashona here will rise, if the present rebels (number estimated about one thousand – most Mashonas and easily licked) are not vigorously dealt with. Mesdames Salthouse, Cass and Dickenson are with us bearing up bravely.

When Relief Column enters Mazoe Valley let them watch closely the dense patches of grass along the roadside, as small parties of rebels lie in ambush. Send some Martini ammunition and we can then give them help. Men in laager, in addition to my patrol, are Darling, Spreckley, Zimmerman [later Rawson] Pascoe, Fairbairn, Stoddard and Salthouse. Mr Stamford Brown met us on the road and accompanied us here. I may mention that we sent most of the rebels – who shot horses and wounded our men – to the happy hunting grounds. Am sending this by dispatch rider (Cape boy Hendrik) who has been promised £100 if he delivers it safely. Send out twelve spare horses; we have two mules and a wagonette.

(Signed) Dan Judson

Inspector Randolph Nesbitt’s Patrol

In Salisbury, Tpr Harbord, one of the men picked by Judge Vintcent wrote: “We left at 10pm. I had just time to scribble a postcard to mother in case I did not come back. Having done so was a great relief to me afterwards. In the Mazoe Valley I had given up all hope of coming out alive. There were thirteen of us.”

The Patrol consisted of: Inspector Randolph Nesbitt, Lieut. G.H. Ogilvie, Lieut. R. Harbord, S.N. Arnott, H.J. Berry, F.R. Byron, J. Edmonds, G. Jacobs, M. MacGregor, C. McGeer, Alexander Nesbitt, H.J. van Staaden and Otto Zimmerman [later Rawson]

Otto Zimmerman, brother of Hugo, wrote: “It was about 10pm that a call went out among the troops in laager in Salisbury for about ten or twelve men to volunteer to relieve the Mazoe laager, and it was known that they were in a very bad state. I volunteered along with others and was very glad to be accepted. As soon as possible we saddled up and mounted with short rations of dry biscuits and biltong strips. It was very dark and we rode in half sections straight through the bush, avoiding road and tracks. We had been riding over an hour when suddenly the party halted; we at the rear did not know why, but the news was whispered along that a Coloured boy was carrying a note asking for one hundred men and a Maxim gun to relieve the Mazoe laager. It was a piece of luck our meeting him and after a short pause it was agreed to proceed with our journey and take him with us.”

Nesbitt’s relief party of thirteen men had met Hendrik with his note requesting a relief party of at least forty men and a Maxim gun and twelve spare horses near the Gwebi River – this was a lucky break as Nesbitt’s party was not following the road and it was night; yet Hendrik willingly returned with them as a guide. It is believed that the party did not take the Tatagura road which was being watched but followed tracks to the south of the Iron Mask Range and through the Mazoe Poort where the dam wall is today.

Saturday 20 June

Rawson states: “The natives now drew off from the immediate vicinity of the kopje and we had a chance to get some food and a wash, and nothing more than a few stray shots during the night disturbed us.”

Nesbitt and his party, including Hendrik, arrived at the Alice Mine fort about 5am on Saturday 20 June with little incident as his report states: “after entering the valley I saw numerous fires on the surrounding hills, and proceeded with great caution, thereby evading an attack until within half a mile of where Mr. Salthouse and party were, when, being obliged to pass through a gorge, the enemy opened fire from dense cover on my left flank. I replied with a volley, and pushed through, it being too dark to distinguish their whereabouts; in this engagement Sgt Nesbitt's horse was wounded.”

Shortly after their arrival a council was held, consisting of Captains Nesbitt and Brown, Lieut. Judson and Salthouse which quickly concluded that the defenders should return to Salisbury immediately. Nesbitt continues: “after making the coach bullet-proof with iron sheets, we left the laager about noon on the 20th June, dismounting six men and putting their horses in the coach; my party now consisted of 12 mounted men, 18 dismounted men and three women. On starting I sent on an advance guard of four mounted men, the same number being left as rear guard, the dismounted and four remaining mounted men being with the coach.”

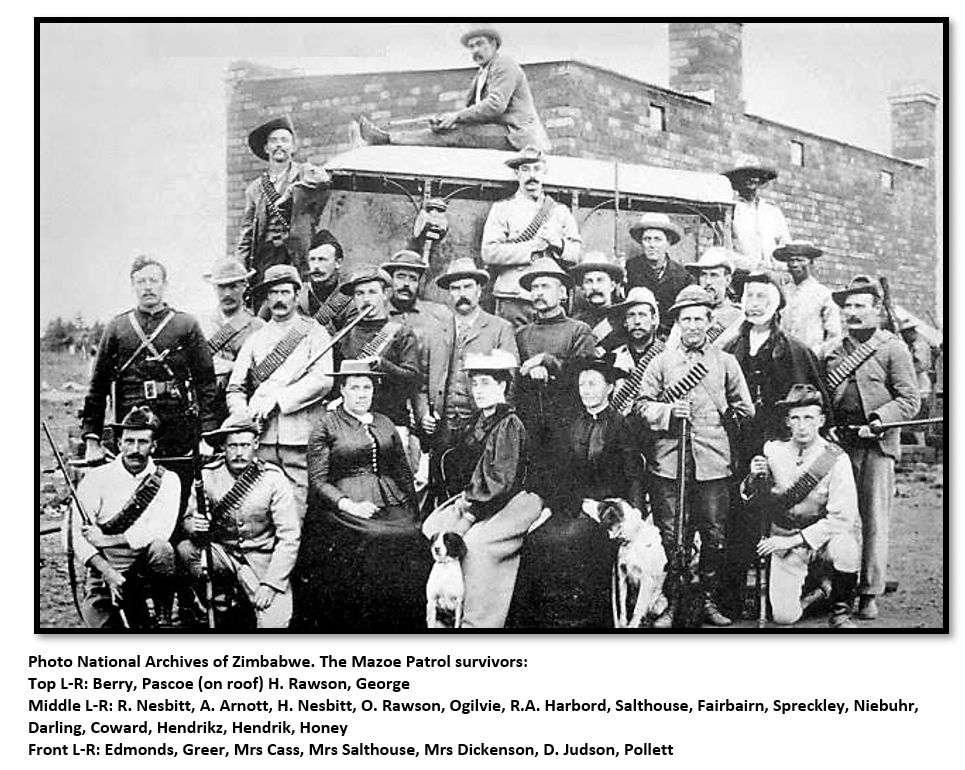

John Salthouse fixed metal sheets to the sides and back of the wagonette; he said they fitted so well they might have been made for the purpose. They can be seen in the photo below.

Darling wrote: “Three of the mules had been shot during the night and one had wandered away, so we put in two mules and four of the newly arrived horses. None of these had been in harness before.”

He continues: “Two of us covered the Matabele tobacco-devotee behind the big rock so that he dared not show his head to shoot the horses while they were being inspanned. The three women and the wounded man (Niebuhr) were put inside the wagon and we got off about 11:30am”

They set off with the three women and eight men of the original Mazoe party, two from the first rescue party, seven from Dan Hudson’s party and thirteen from Nesbitt’s Patrol – a total of thirty-three. [See the table of persons who took part below]

There was no sound from their attackers as they prepared to leave; all knew this meant that they were lying in wait on the road. So, at every potential ambush point, Judson and his advance guard went forward, firing into the grass and bush which lined the road so that the wagonette passed safely through. Harbord wrote: “Whenever the fighting became very hot, we four dismounted and fired from behind our horses.”

They had not travelled a kilometre up the Tatagura road before they were fired upon on both sides of the road; their attackers armed with Lee-Metfords, smooth-bore muskets and Martini-Henrys, and here Troopers McGeer and Jacobs were shot dead. The perilous situation was relieved by the advance guard capturing some higher ground to cover the wagon and Pascoe climbing onto the roof of the wagon from where he advised the others of the positions of their attackers; miraculously he remained unharmed despite a bullet through his hat and another cutting his shoe lace. From here Pascoe gave information on the whereabouts of their attackers and managed to put in many telling shots. [In the photograph below Pascoe sits on the wagonette roof]

Pollett says: “Behind every tree and rock seemed to be posted a native and although smoke was seen proceeding from the hills and kopjes yet seldom could we get a glimpse of the enemy.”

Just as they were passing the Etna Mine, Pollett who was riding behind the wagonette reported: “I was riding next to Lieut McGeer and asked if him he would mind changing places with me i.e. let me ride on his left instead of his right, as I could shoot better mounted that way. The poor fellow declined because he had his hands full with a very restive horse and strange to say, five minutes later he was shot dead. Being my half-section, and therefore riding close to me at the time, he nearly swept me out of the saddle when throwing his arms back with his last gasp. The horse dashed off, but Charley Hendrikz raced after it and eventually brought it back.”

Salthouse wrote: “On our way to the valley and main road the enemy commenced their attack. When we reached the first donga, near the Vesuvius Mine, and about two miles along the valley, the firing became terrific. Here Mr. J. Pascoe, of the Salvation Army, with dauntless courage, mounted on the roof or hood of the wagonette, where he remained throughout the fight, firing and advising us of the movements of the enemy. The surrounding kopjes and even the grass seemed alive with men, and the bullets rained upon us. It appeared to us, indeed, like the Valley of the Shadow of Death; no other words seem adequate to portray the scene.

We now saw for the first time that among the enemy there were 30 or 40 mounted men, and these, during the whole of that terrible journey, never ceased to harass our rear. From the Vesuvius donga we struggled on and reached the Mazoe lime works. Here we had to make a halt and fired volley after volley at the rebels, who were closing in on our rear. It was at this place that Charles Hendrikz of the B.T.A. store, greatly distinguished himself by racing after and capturing McGeer's riderless horse, which had bolted. Immediately after leaving this point, we sustained our first loss, Lieut. McGeer, of the Salisbury Field Force, falling mortally wounded; Capt. Nesbitt and Mr. J. Edmonds, of the Rhodesia Horse, almost at the same moment, having their horses shot dead under them.”

All the time the sun poured down and the footsloggers who ran much of the distance, were particularly exhausted, but sometimes managed to hang onto the stirrups of the mounted men or jumped on the narrow steps of the wagonette for brief intervals until they regained some strength. Inside the women were refilling bandoliers with ammunition whilst bullets rattled off the iron plates. Pollet said: “A great many had muzzle-loaders into which they crammed almost anything handy, pot-legs and even stones…A large number of the enemy now began harassing our rear and the further we went the more we had to contend with from this quarter until at last they got so near that we were ordered to dismount and fire three or four volleys into them, this kept them off for a bit, but they never ceased to harass the rear.”

Hugo Zimmerman (later Rawson) praised Pascoe’s bravery, but added: “Though he was very much exposed, I think that most of us would gladly have exchanged places with him, if only to get the ride, as the heat and dust, combined with carrying a rifle which was nearly red-hot with rapid firing, created a thirst that was nearly unbearable.”

Crossing the Tatagura River

Seven miles from the Alice Mine, where the Tatagura River crosses the road was a dangerous spot for an ambush and Judson ordered the advance-guard: “to fire into the grass where last time the enemy had been hidden, but, strange to say, whether they anticipated this action on our part or whether it was by accident, they had removed themselves just about fifty yards up the hill, and here such a fusillade met our advance-guard as to completely disorganise it.”

Salthouse wrote that one of the leading mules was shot through the head but continued running; almost immediately after that the offside mule fell, mortally wounded: “Mr Brown and I struggled to cut him loose. Our task was hardly completed when our hearts sank to see the other wheeler fall. I was just able to save myself as he fell towards me. We cut him loose, also.”

Rawson wrote: “The natives were now firing very heavily, and it was only the fact of their having such old and obsolete weapons that saved us, as they were lying close to the road in the long grass. Pascoe now got on to the roof of the ambulance and was able to give us information as to the movements of the natives. Though he was naturally very much exposed, I think that most of us would gladly have changed places with him, if only to get the ride, as the heat and dust, combined with carrying a rifle which was nearly red-hot with rapid firing, created a thirst that was nearly unbearable. The natives did not give us a moment's peace, and to make matters worse, they shot two of the horses in the ambulance which had to be cut loose, and the remaining four had to pull the ambulance. Shortly afterwards Van Staden and Jacobs were shot dead and Hendricks, Ogilvie and Burton were badly wounded. When we got to the Tatagura River the natives were so close and determined that we could not even drink, and I shall never forget trailing my hat in the water as I ran through and sucking the brim for miles.”

At this spot James Burton, the storekeeper was shot through the face, the bullet entering under the left ear and exiting through his right cheek. He crawled into the wagonette where: “he fell bleeding among the horrified women” who recovered sufficiently to bandage him and stop the bleeding. [See Burton’s Diary account below] Soon after Jacobs and Van Staaden of the advance-guard were killed with their horses and Charley Hendrikz was shot through the jaw.

Harbord went around a sharp corner and: “heard a lot of firing and nearly rode over Van Staaden who was lying in the open, the side of his head shot away and his horse dead under him. Just at that moment two Cape boys, well-dressed and armed with rifles, jumped out of the grass in front of me. For half a second, I thought they must be our boys, having no idea that the Mashona had any Cape boys with them, and it was decidedly surprising to see men in khaki clothes, breeches and boots…I jammed my spurs into my horse and galloped for all I was worth, killing, as I passed, one of the Cape boys who had just fired at and missed me.”

He went on three hundred yards and saw Ogilvie ahead of him: “I halloed Ogilvie who rode back to me, his face and shirt splattered all over with the blood from Hendrikz’s wound.” Ogilvie was the only one left of the advance-guard.

Arnott and Hendrikz leave the Patrol

When Arnott saw how badly Hendrikz was wounded and was unable to ride, he took his reins and led his horse and together they left for Salisbury which saved Charley Hendrikz’s life. His horse collapsed just after the two men had crossed the Gwebi River and was seen later by the Patrol.

The fighting continues

Harbord and Ogilvie rode back to the wagonette: “the wagon then came on and Ogilvie and I, still keeping in advance, galloped up every kopje and rising ground in front of us and fired over the top of the wagon and over the head of the last men” at their attackers who were running behind them and along the hills each side of the road to take up positions ahead.

At the Tatagura drift their situation seemed hopeless when two horses were killed and blood pouring from the nose and mouth of the wounded leader. Judson reported: “At the time Hendrikz was wounded we were in a critical position. Three horses were dead in the traces and four badly wounded, and rebels firing at us from a few yards off in the grass.” The women in the wagon continued to refill the bandoliers with ammunition and tender the wounded.

Judson continues: “I took Tprs. Ogilvie, Harbord and Pollett to the tops of a series of small kopjes, and from these we covered the wagonette and dismounted men, allowing them each time to get well ahead before vacating our position. By these means we checked the advance of the rebels, killing a good number of them, including two mounted men, of whom there were about ten.” After crossing the Tatagura River the country became more open giving the flanking parties more opportunity to spread out and clear the way, and as they reached the head of the valley their attackers gave up the chase.

Salthouse wrote: “Our advance-guard then left the road and continually taking up position on any little hill or knoll they could see, kept pouring lead on the enemy waylaying us in the grass ahead and across the Tatagura River, which was now in sight. Here we had hope to quench our raging thirst, which had been growing momentarily more and more unbearable, but it was not to be. The firing was too terrific and only one or two, as they rushed past the water behind the wagon, was able to catch up in their hat a mouthful of mud and water.”

Hugo Zimmerman (later Rawson) remembered their frustration: “When we got to the Tatagura River, the natives were so close and determined that we could not even drink and I shall never forget trailing my hat in the water as I ran through and sucking the brim for miles.”

Darling said: “Several bullets went through the roof of the coach and the iron sheets were dotted by bullets and slugs, but none went through. The wounded men were asking for water and, in fact, we were all extremely thirsty, but although there was a tank under the coach, we could not get at it without stopping. Even when we reached the river near the Salvation Army farm, we could not stop, but galloped through. I was able to keep up all right even when our horses were trotting, but some of the men were very exhausted.”

From the river, the road pulled up steeply, around a long ridge on the left was a blind corner and Judson saw some of their attackers making for the ridge to ambush them on the corner. Judson, Pollett and Ogilvie raced ahead to get there first. Pollet reported: “Lieut. Ogilvie, Lieut. Judson and myself having the only three horses that were not wounded galloped on to try and reach the top of this kopje before the enemy. We succeeded by getting up the opposite side and rather surprised sixty to seventy natives who were coming up at the foot by letting them have two or three volleys in quick succession. Then for some reason I can never account for, I proposed we should cheer, which might perhaps make the enemy think reinforcements were at hand. Anyway, our own fellows with the van were also misled and took up our cheers lustily. This had the desired effect. The natives immediately began to withdraw and thus afforded us time to get into the open country.”

The ruse was soon discovered and they were pursued by a raking fire, but the countryside now became more open and the attackers more exposed to the accurate shooting of the Patrol. Once out of the Mazoe Valley, they were still pursued, but with no more casualties.

Near the Gwebi River their wounded leader horse who had performed so valiantly was released from its harness and the wagonette pulled by the three remaining horses which were outspanned as soon as they reached the Gwebi River. Harbord said the water was stagnant and muddy, but: “I lay down flat in the mud and buried my face in it, thinking it real nectar of the gods, the most delicious drink I ever had.”

They only rested fifteen minutes before a false alarm had them harnessing and saddling their horses once again and moving on until they reached Salisbury. Nesbitt stated: “I estimated the enemy's strength to be at least one thousand five hundred, many of them being armed with Lee-Metford, Martini and Winchester rifles, and appearing to be well supplied with ammunition. I have every reason to believe that Cape boys and Matabele’s were the leaders of this attacking party. I compute that the enemy's loss must be about one hundred.”

Salisbury was reached in the late evening; the nearly fifty kilometres having taken almost twelve hours. Pollett writes: “When we arrived the whole town was in laager and of course the first sign of life we stumbled against was one of the pickets, on hearing who we were his excitement was so great that he rushed towards the laager with the news. The main guard seeing him run in gave the alarm and in a moment, everyone knew the pickets were coming in. As we drew near the whole wall of the laager presented one long line of rifles, but fortunately the picket soon made himself understood and such was the excitement at the moment that I do not think he was even censured for his conduct.

By the time we arrived at the laager gates every man, woman and child in the place had turned out to do us honour and we were greeted to use Mr Salthouse's words ‘as men and women might be who returned from the dead.’ Cheer after cheer went up and I think we deserved them.”

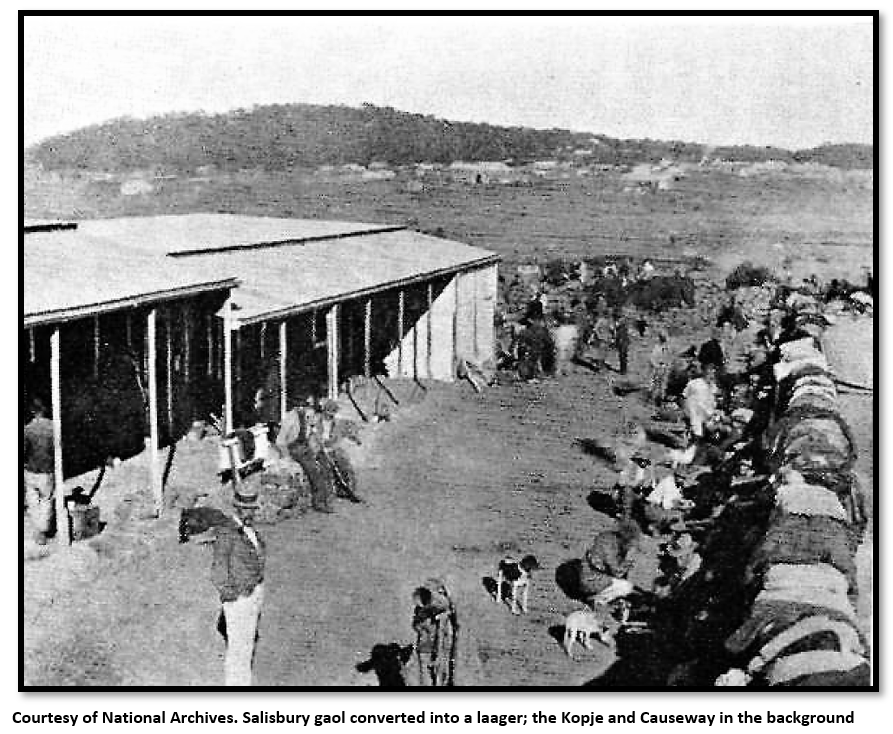

Inside the Salisbury laager

Maynie Judson (Dan’s wife) had been ordered to be in the laager at the Salisbury gaol before sunset where she slept in the condemned cell with three other women: “The confusion of such hurried preparations was bewildering. There was all the paraphernalia of a small baby, mattress, bedding and plenty of blankets because the nights were bitterly cold…my belongings made a goodish pile and how I got into the laager a mile and a half away, I don’t know. But I arrived there in the late afternoon, into an absolute pandemonium of women, crying children and mounds of bedding and baggage, dust, dirt and utter confusion.

In the early evening [20 June] we strolled down to our new home [the laager] to install ourselves before dark, when a man came rushing up to us and said: ‘Have you heard the news? What news? Charley Hendrikz has just ridden in, shot through the jaw, and says the Mazoe Patrol is cut up. They were fighting for their lives when he left and there isn’t a hope.’ There was a deadly silence. No one said a word. The man had blurted this out in a torrent of excitement and now, looking at us in dismay and sensing he had made some blunder, he turned and walked slowly away.”

After his horse had collapsed at the Gwebi River, Hendrikz had climbed behind Arnott and arrived safely in Salisbury about 5pm; Judge Vintcent and the Defence Committee immediately held a meeting.

Maynie Judson recalls the Judge ordered the laager garrison to line up and addressed them. “Lines of men in mufti under the lee of the high jail wall, rifles over their shoulders, and the Judge alone in front of them, looking haggard, drawn and ill. He had something hard to do and that was to tell them that…the Committee were forced to decide that no further help could be sent and that the Mazoe Patrol must be left to its fate; and ‘May God help them for we can do nothing more.’”

There was a slight murmur of dismay and resentment, but the Judge went on to say that they had a responsibility for the women and children, there were very few rifles in Salisbury, and also, they had no horses to spare and there was a danger of the town being rushed at any moment…this cast a gloom over the whole place.

Maynie again: “I just felt dazed and unable to think, everything seemed unreal and I stood there looking on and no one said anything to me. It was getting dark and time to put baby [Mazoe] to bed, which I did…The whole place was very quiet and still, everyone having settled down for the night. Very few sounds penetrated beyond the doors of the cells; perhaps a child crying somewhere, or the opening and shutting of doors and voices of people suddenly talking.

It was about 10:30 when all of a sudden, a faint shout was heard in the distance, and then a shot. We looked at each other, wondering if the long-threatened attack had come at last. The sounds came louder and nearer, shouting, cheers and hurrahs, and the whole place galvanised into sudden life. People stamped down the corridors and called out to each other in breathless excitement.

We were bewildered, wondering what had happened and what we ought to do. Then clearly above the din we heard cries of ‘Mazoe! Mazoe!’ and cheer upon cheer broke out from that big crowd of excited and joyous people. It was a wonderful moment, but I couldn’t believe it and just stood there dazed, in my nightgown, unable to move. Someone rushed in to say Dan was safe and later he appeared, utterly exhausted, his tunic covered in blood and hardly able to stand.”

Mrs Delphie Fleming, who was also in the laager wrote: “One outstanding event which I could never forget was the arrival of the famous Mazoe Patrol after we had supposed they had been wiped out. Two members of the Patrol [Arnott and Hendrikz] had been cut off and brought us the news. In the women’s quarters several poor things had husbands, brothers or friends in the Patrol. It had been a most trying day for us. The news caused a good deal of hysteria in the bog ward, where a number of women and children were crowded together.

Everything had quietened down by 8pm and we were all locked in for the night as usual. Suddenly, an hour or two later, there was an outburst of loud shouting outside. It was really the outlying picquets firing as the forlorn group round the famous light wagon stumbled out of the darkness. The poor women in the big ward thought it was the Mashona attacking the laager and panic reigned.

In the middle of the confusion the jail doors were thrown open and the three women supported inside. [Mesdames Cass, Dickenson and Salthouse] You can imagine the reaction. Mrs Salthouse told me that the worst part of the journey was the twelve miles from the drift at Mount Hampden [Gwebi River] to Salisbury. They had been under fire the whole way, but the Mashonas left them when the party got into the open Gwebi flats. As they toiled along mile after mile in the darkness, doing the best they could for the wounded in the wagon, their hearts sank when nobody came to meet them and they began to fear that Salisbury was in the hands of the Mashona and that the inhabitants had been wiped out.”

The situation in Mashonaland remained perilous; those at the Alice Mine may have been rescued, but the Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga was not over and resistance was far from over. James Darling wrote to his father: “It was a close call; in fact, it was the concentrated effort of several miracles that any of us came out alive. All the Mashonas in the country have risen and whites are being massacred everywhere. From the outlying districts men are getting in every day by hook or crook, but most of the outsiders have been killed. Poor Herbert Eyre has been murdered on his own verandah. The natives came and said they wanted work – boys he knew – and while he was sitting on his doorstep talking to them, they fell on him. It is awful to have to stay in town doing nothing while one’s friends are being slaughtered.

A company of eighty men has just returned from Umfuli where they rescued a few people, [see the article on fort Hill at Hartley Hill on zimfieldguide.com] having a few of their party wounded. A patrol sent to the Jesuits’ Mission twelve miles from here brought in seventeen persons, including eight fathers and lay-brothers.

A few small patrols are being sent out on rescue operations, but there are not more than five hundred men all told, we can’t do much until reinforcements arrive. Our own men who went to Matabeleland are on their way back. Also, sixty under Captain White are making a forced march from Bulawayo. Some of the Natal contingent are here and more are expected with a lot of horses. It is reported that five hundred regulars from Cape Town under Lieut-Col. Alderson are likewise coming to our assistance.”

The Mazoe area was then largely abandoned for three months until Lt-Col Alderson’s Imperial Forces arrived to reinforce the British South Africa Police and combined patrols went into the Mazoe area to wear down the Mashona opposition.

Those not in this photo include James “Jim” Burton who was shot through the face and was still in hospital, Capt. Stamford Brown, Stoddard and Byron.

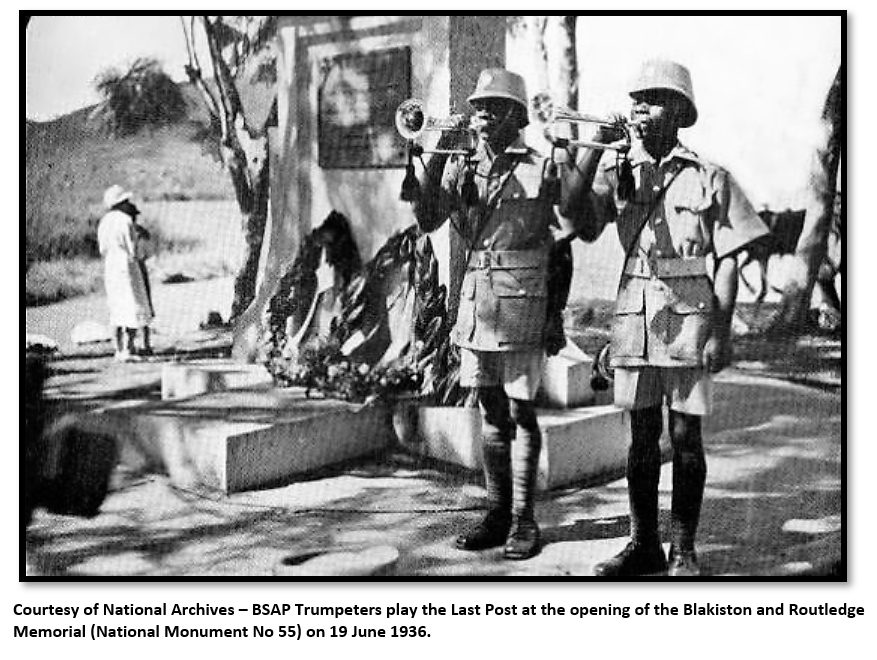

The burial site of Blakiston and Routledge is covered in a separate article on the 1896 Rebellion Memorials.

Persons who took part in the Mazoe Patrol 1896 |

| |

Resident at Mazoe |

|

|

Charles Annesty | Killed Thursday, 19 June | Prospector killed near the Alice mine fort |

James Archer Burton | Wounded Saturday, 20 June | Manager of Holton Syndicate store |

Fairbairn |

| Moving ten-stamp mill from Vesuvius to Alice mine |

Edward T. Cass | Killed Thursday, 18 June | Superintendent at the Salvation Army farm |

Mrs Ada Cass |

| Mazoe resident |

James ffolliot Darling |

|

|

James Dickenson | Killed Thursday, 18 June | Mining Commissioner and Justice of the Peace |

Mrs Jane Dickenson |

| Mazoe resident |

William P. Faull | Killed Thursday, 18 June | Bricklayer moving ten-stamp mill from Vesuvius to Alice mine |

George |

|

|

John Pascoe |

| Salvation Army worker |

HH. Pollard | Killed about Thursday, 18 June | Mazoe district Native Commissioner |

John Salthouse |

| Alice Mine manager |

Mrs Salthouse |

| Mazoe resident |

H. Spreckley |

| Assistant Mining Commissioner |

Routledge, Thomas G. | Killed Thursday, 18 June | Telegraphist stationed at Mazoe |

Stoddard |

| Moving ten-stamp mill from Vesuvius to Alice mine |

First rescue Patrol |

|

|

Blakiston, John L.L. | Killed Thursday, 18 June | First rescue party on Wednesday, 17 June |

Hendrick |

| First rescue party on Wednesday, 17 June |

H. Zimmerman (later Rawson) |

| First rescue party on Wednesday, 17 June |

Judson's second rescue Patrol |

|

|

Capt. S. Brown |

| Second rescue party on Friday, 18 June |

Lt Dan Judson |

| Second rescue party on Friday, 18 June |

Tpr W. Carton-Coward |

| Second rescue party on Friday, 18 June |

Tpr C. Hendrikz | Wounded Saturday, 20 June | Second rescue party on Friday, 18 June |

Tpr W.S. Honey |

| Second rescue party on Friday, 18 June |

Tpr E. Niebuhr | Wounded Friday, 19 June | Second rescue party on Friday, 18 June |

Tpr H. Pollett |

| Second rescue party on Friday, 18 June |

Nesbitt's third rescue Patrol |

|

|

Tpr S.N. Arnott |

| Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Tpr H.J. Berry | Wounded Saturday, 20 June | Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Tpr F.R. Byron |

| Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Tpr J. Edmonds |

| Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Lieut. R. Harbord |

| Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Tpr G. Jacobs | Killed Saturday, 20 June | Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Lieut. C. McGeer | Killed Saturday, 20 June | Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Tpr M. MacGregor |

| Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Tpr A. Nesbitt |

| Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Capt. R. Nesbitt |

| Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Lieut. G.H. Ogilvie | Wounded Saturday, 20 June | Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Tpr H.J. van Staden | Killed Saturday, 20 June | Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

Tpr O. Zimmerman (later Rawson) |

| Third rescue party on Saturday, 19 June |

James Burton’s Diary

James Henry Archer Burton kept a diary which was quoted in Heritage No 15 in 1996. After working as a barman for Susman & Co. in Salisbury which: “takes the cake for drunken men of any town (bar none) that I’ve seen” he accepted a job at Homan’s Store and Wayside Inn at Shorts drift on the headwaters of the Umniati River from March 1895. This was one of the stops on the Bulawayo – Salisbury coach route and Jim served the passengers and coachmen meals – often in the middle of the night. He says of it: “This really is a godforsaken hole of a place neither fit for man or beast” and in March took up a new post at Mazoe as the storekeeper with the Holton Land and Mining Company.

Soon after he settled in at Mazoe Jim gave his prospecting licence to Charles Annesty: “on half shares, he to do all the work and pay expenses” the agreement being authorised by Spreckley, the assistant Mining Commissioner. Spreckley and Burton walked over to Annesty’s camp [Annesty was killed on Friday 19 June 1896] to see the claims on the same range as the Alice Mine and saw gold in their pannings of their ‘Rita May’ claims. Everyone suffered from fever; Routledge was sent into Salisbury hospital in February.

On 27 March Henry Pollard sent Jim Burton a note saying the amaNdebele had risen and killed Europeans in Gwelo. The next day Pollard [killed on Thursday 18 June] shot two of Jim’s cattle which had cattle sickness [Rinderpest] It had begun in Eritrea in 1887 with imported Indian cattle and spread throughout Africa; by March 1896 it had crossed the Zambezi River. On 1 April Pollard had shot the remaining cattle: “damn cheek I say.” The diary entries are now occasional as Burton has fever, but he reports more cattle shot and his entry on the 16 June records: “Heard that the Matabele were at the six-mile creek, The Beatrice Mine and had killed all hands. It beats the devil that they don’t let us know what’s going on…Now we hear that the Matabele are killing whites three miles from Salisbury. A jolly look out. Only three of us here and all sleep-in different places – well, all I hope is that I get one or two before they get me.”

17 – 20 June Burton joined the others in the Alice Mine fort and left with the others on Saturday 20 June. He was cutting a dead horse from the traces when he was shot at point-blank range, the bullet took off the left lobe of his ear, passed through the roof of his mouth and exited below the right eye. Troopers van Staaden, Jacobs and Hendricks were shot dead as they tried to cut the other dead horse out of its harness, Sgt Ogilvie and Burton were seriously wounded.

Mrs Salthouse, the Alice Mine manager’s wife, left the armour-plated wagonette and pulled Burton inside and bandaged his wounds with material from her petticoat, saving his life. Newspapers in England reported that Burton had been: “shot through the head and lived” – the news was received by the public with amazement and by the medical profession with disbelief.