The old Transport Road

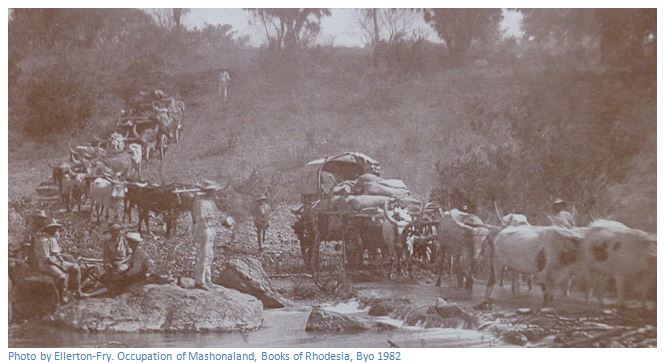

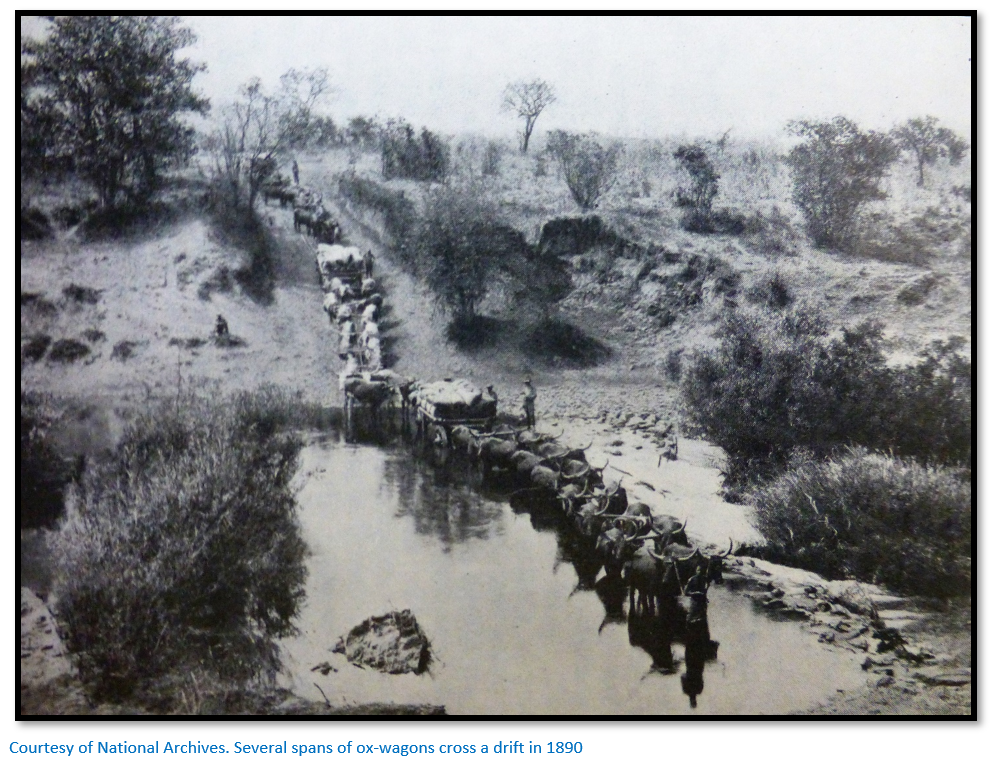

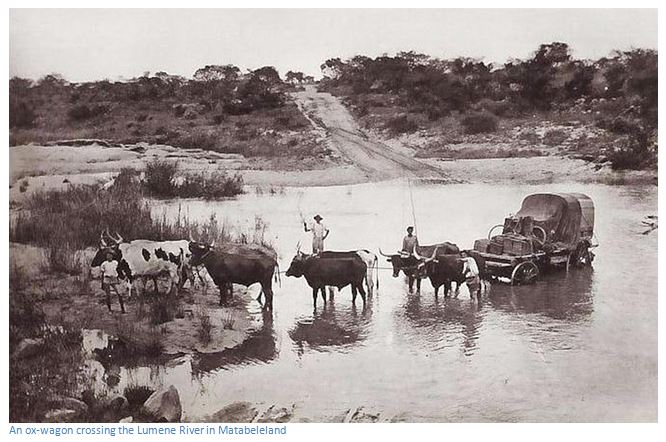

Stanley Portal Hyatt came to Rhodesia on the Great northern Road when railhead was at Palapye Siding in Botswana. In his words: after that the only way to get your goods to Bulawayo was by ox-wagon and after the rinderpest when 90% of the cattle had been killed, you paid transport rates of twenty-five shillings per hundred pounds weight. Hyatt considers the rate was quite moderate as the journey was over two hundred miles (320 kilometres) along an almost inconceivably bad road, with long, dry stretches with no water for the oxen, the possibility of lions at every outspan. Salted oxen (those which survived the Rinderpest) at that time cost £40 each, making your span worth £640. The ox- wagon cost was much less; hundreds had been abandoned by the roadside; a wagon costing £100 at the coast could be bought for £4 – or you could just take them and trust to luck not to meet the former owner later on!

He worked on the Geelong Mine for two years and saved enough to start trading and transport riding. By 1897 the railway had reached Bulawayo and practically the whole country was supplied from there. Scores of wagons left the town every day, loaded with stores of every conceivable kind, from boilers weighing eight thousand pounds to parcels of millinery. Hyatt says the good point about Bulawayo is that the streets are so wide that you can turn a full span of bullocks in most of them. Beyond this, it has no merits whatsoever! When the ground is dry, the red dust is abominable, choking everything; whilst a single shower of rain changes that dust into a slimy wet mud. Generally speaking, he thinks the average Bulawayo man could neither ride nor shoot; he would have lost his way had he gone alone three miles from the township; yet he invariably wore riding-breeches, puttee leggings and a hunting stock, whilst a stranger, hearing him talking to a barmaid, would have taken him for one of the original band of pioneers.

His driver Joseph ran away, but before long a little Basutu strolled up and asked if he is the white man who wanted someone to train his very little cattle, who were now cheeky and would not pull, because a schelm called Joseph, a useless Zulu, had been spoiling them? Hyatt never knew his age; he thought he was about forty, although his queer wizened face, with horse hair plaited into the ends of his moustache, to make it appear long and fierce, might have been that of a man of sixty-five. He was small and slightly built, though tough as a watch-spring, absolutely tireless, and perfectly indifferent to danger or hardship. Wet, cold, hunger, thirst, heat- all these seemed to leave him unmoved, the only thing that did affect him was fever. His costume was always the same – blue dungaree trousers, ragged at the bottoms, a tattered canvas shirt, and a huge sombrero.

His name was Amous, he explained, adding, quite truthfully as it turned out, that he was the best driver in the country. Hyatt engaged him at once, at £3 for a month. He saluted, borrowed some tobacco, and then went off to inspect the cattle. An hour or two later he returned, informed they were “cattle indeed,” then set to work to overhaul the wagon and gear, keeping up a running fire of uncomplimentary remarks concerning the Zulu character. Joseph’s whip was tossed aside contemptuously as, “fit only for a Zulu, or a thief from the Cape Colony.” His own whip was always thirty feet in length, ending in a voorslag thin as a piece of twine and he liked his whip stick to be fifteen feet. He never touched his bullocks with the heavy part of the lash, never hit them on the back, never hit them at all, if he could avoid doing so, the crack of his whip was sufficient.

When they stuck really badly with the cattle up to their bellies in liquid mud, the only thing was to unload all they carried, make a sledge, drag all the goods over the mud, then sixty feet of chain was tied to the dϋsselboom on the empty wagon to pull it out. It could take over five days to do half a mile in the wet season. He says a single day’s rain, and what had been for months past, a level, treeless stretch of plain becomes a hideous morass, extending sometimes, with short breaks, for miles. Hyatt actually once had a hind-wheel, four and half feet in diameter, out of sight in that mud.

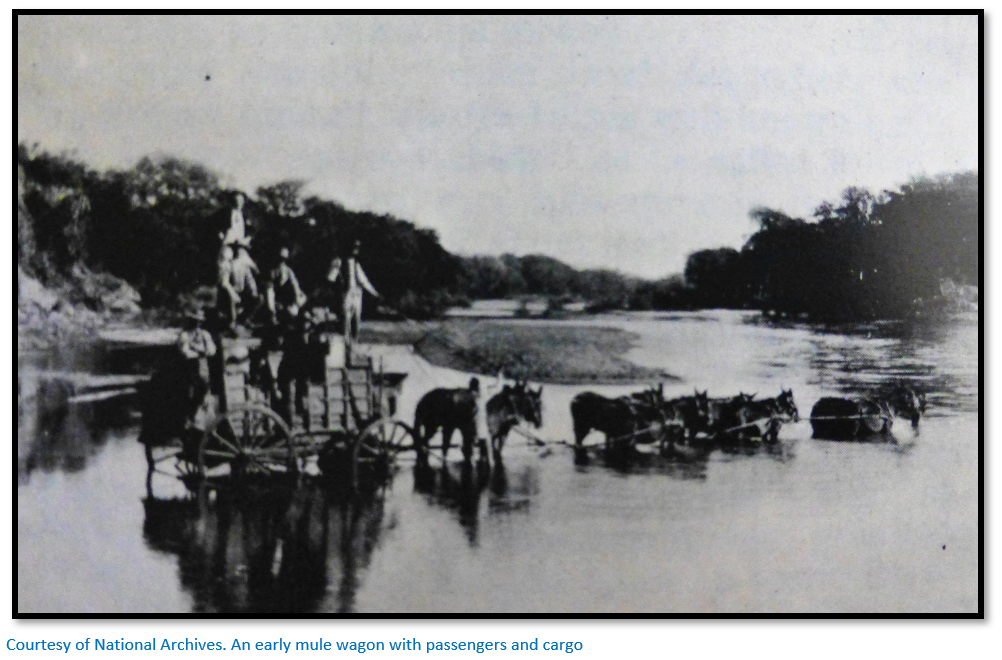

On the treks from Bulawayo to Fort Victoria (Masvingo) they went via Gwelo (now Gweru) with miles and miles of terrible black vleis, heart-breaking mud, inconceivable to anyone who has not seen it. On the Gwelo Road, you would find places where the track was three-quarters of a mile wide and you never knew when you would stumble into someone else’s “grave,” a hole where another wagon had been dug out and had filled up with liquid mud. One night on the Gwelo-Bulawayo road, they had outspanned at dusk, and just finished their evening meal, when they heard a great deal of shouting about two hundred yards away. Amous put his head into the tent, “it’s the coach, it’s got right off the road, and it’s stuck.” The coach had blundered into a very bad mud hole, and the mules could not possibly shift it. Within a few minutes, Amous had the black span in the yoke; and it did not take those perfectly-trained beasts long to hook out the coach. There were some half-dozen men in that coach and I think I have never seen a more utterly exhausted collection. They had been seven days coming down from Salisbury (now Harare) travelling, or trying to travel, night and day, practically without any chance of sleep, for you cannot rest much in a straight-backed coach seat. I think it was nine times that they had been overturned.

Stanley Hyatt has very little positive to say about the stores between Bulawayo and Gwelo. The buildings were as bleak and comfortless as possible, the huts had mud walls, thatched roofs, the largest building, a square one, would be canteen at one end, store at the other, separated by a partition, the bar fittings consisted mainly of whisky cases. A round hut, innocent of window frames or doors, served as dining room. The table-cloth, a piece of white limbo, remained on from meal to meal, forming a favourite promenade for the flies. Table ware was all of enamelled iron, badly chipped, and the food was unspeakable. Still, as one store-keeper remarked to me once “who the blazes wants to eat when he gets off the coach after twenty-four hours of jolting and dusk? All he cares about is a drink, or as many drinks as he’s time for while they’re changing mules. Very few of them ever touch the food.” I have seen the food provided and I was not surprised at the reluctance.

It was not uncommon for a transport-rider to spend a month or even six weeks waiting for the waters of a river to go down in the wet season. When you find you are held up, you drove a small stick into the bank, just at the edge of the flood, and then go back to the wagon, intending to smoke, or fall asleep for a full three hours before you go and see if the level has fallen. That stick becomes an obsession with you. Your spirits rise or fall with the water. A drop of an inch, and you give all your boys extra sugar; a rise of half an inch and you throw boots at the cook-boy, who probably deserved it in any case. The longest time he ever had to wait was a fortnight, though his youngest brother was once over six weeks on the bank of the Tebekwe; but as he told me afterwards it didn’t seem too long as he was too ill with fever to take much notice of anything. Stanley and later his brothers traded for grain and cattle to the south east of Masvingo, the inhabitants of the town were pessimistic of their chances of success, but they establishes a trading station some eight weeks travel from Bulawayo, where they traded livestock, cattle, goats, fat-tailed sheep and chickens which they paid for in gold sovereigns.

In some areas lions were such a nuisance, the kraals had been abandoned. From one kraal on the Lundi (Runde River) the lions took sixteen people in six weeks.

As a rule, the only alcoholic liquor they carried on the wagons was “Squareface” Hollands Gin. He says “whisky merely made you bilious, and left you ready for the ministrations of the malaria-bringing mosquito. Hollands washed out the organs and saved you from the risks of Blackwater fever. I never knew any other man who took the risks we did, who had fever so constantly and yet escaped Blackwater. I put our immunity down entirely to our use of Hollands.”

He writes for a full sixteen pages about the oxen that made up his spans, although he wrote his book nearly ten years after he left the country. His favourites were Biffle, Appel, Jackalass, Bandem, Sixpence, Englishman, Swartland, Dudmaaker, and Shilling. Stanley Hyatt was in Bechuanaland (Botswana) when the Rinderpest swept down from the North; hundreds of wagons, tens of thousands of pounds worth of stores, machinery, goods of all kinds, abandoned on the road. The cattle died within a few hours, died in the water if possible, poisoning the whole countryside, and then the transport-rider, utterly broken, utterly helpless, abandoned all, and with a boy or two to carry his kit, tramped back to the nearest outspan, to curse his luck, to drink so as to forget that luck, and perhaps to die. Rinderpest spared about ten percent of cattle. For Stanley and his brothers went from owning some six thousand pounds worth of property when the disease broke out, a few months later and they were only just able to pay their fares out of the country.

Acknowledgement

S.P. Hyatt. The old Transport Road. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1969