Lord Randolph Churchill’s visit to Rhodesia in 1891

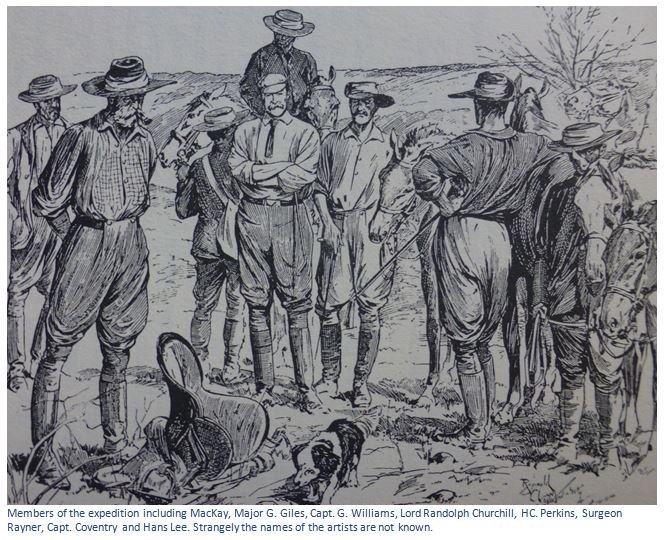

An early visitor to the country in 1891 was Lord Randolph Churchill, father of Sir Winston Churchill and a shareholder of the BSA Company, who was paid £100 for each letter he wrote for the Daily Graphic describing his travels. His entourage included HC Perkins, a well-known American mining engineer and a collection of Captains and Majors all familiar with trekking so as not to expose Churchill to the difficulties of frontier life.

Churchill had considerable personal gifts, but also an overbearing personality and was famously described in Salisbury (now Harare) as someone who would offer you tea; whilst he himself drank champagne!

His letters must have alienated him to a broad sector of the population in South Africa, that of all Afrikaners, but then again perhaps they did not read the Daily Graphic.

His reports on the gold mining prospects of Rhodesia were not positive. Lord Randolph Churchill’s accounts were very different from all those that promised “a new Eldorado.” “In my opinion, at the present time all that can be said of Mashonaland from a mining point of view is that the odds are overwhelmingly against the making of any rapid or large fortune by any individual.”

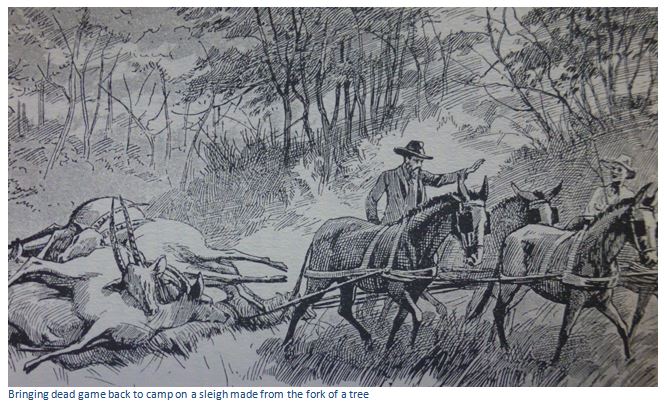

For Lord Churchill the whole journey was a glorious hunting trip which is why Hans Lee, son of John Lee of Mangwe Pass fame was part of the expedition. He shot antelope of all kinds, sable, wildebeest, eland and hartebeest, enjoyed chasing ostrich on horseback and thought the presence of lions added an exciting variation.

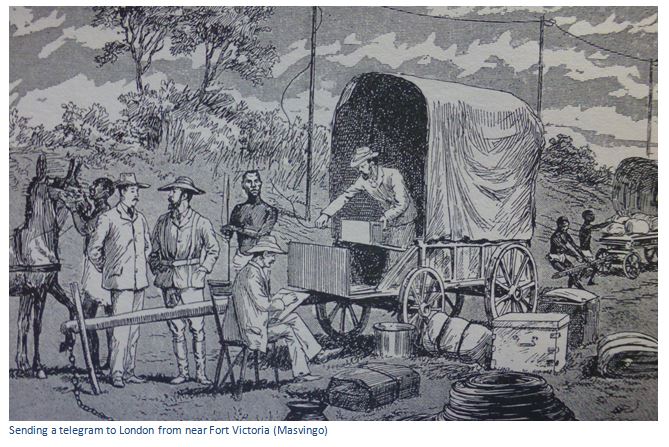

There is no mention in his book of the artist who drew the Daily Graphic sketches shown below.

Churchill died on 24 January 1895 so he was touring within five years of his death. There have been many rumours that his irascible behaviour was conditioned by syphilis and reference is made to this in the body of the article.

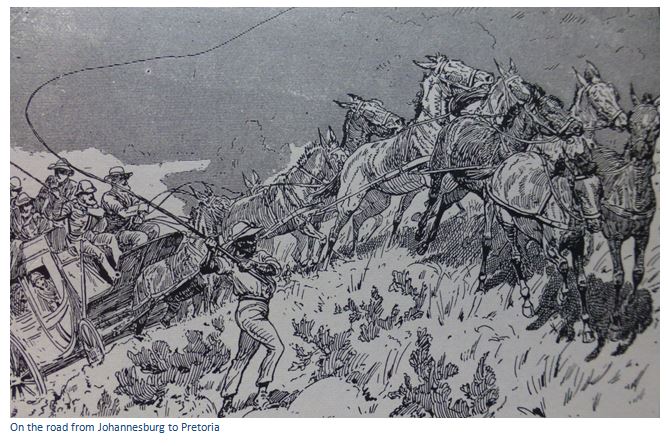

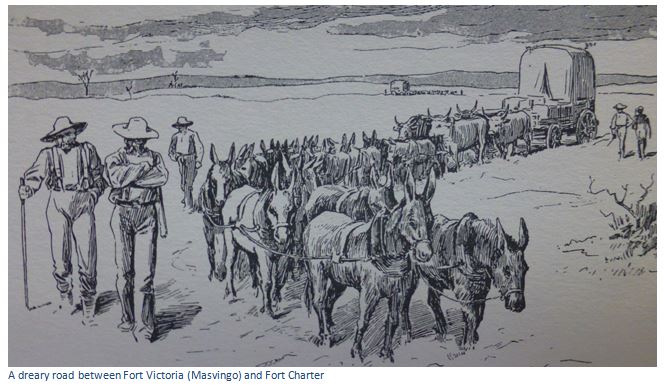

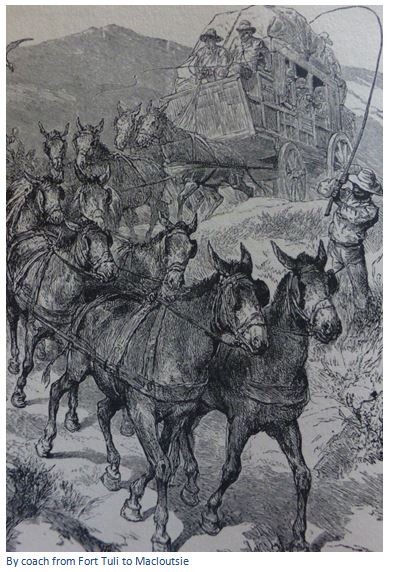

Lord Randolph’s party journeyed by sea to Cape Town and then by rail to Kimberley where they visited the diamond mines, then by rail to the terminus at Vryburg and then a four day coach journey to Johannesburg; the coaches pulled by mules.

He writes; “when driving a team of mules the whip is in operation every minute, constant flogging alone inducing these stubborn animals to do their best. In spite, however, of all this effort and apparent harsh treatment, an average speed of about six miles an hour is all that can be realized. Roads there are none, deeply rutted tracks are followed. When the ruts get too deep for safety the track turns slightly aside, and to such an extent does this sometimes occur that in places the track occupies a width of a quarter of a mile or more. Swinging, bounding, jolting, creaking, straining over this extraordinary route, the coach pursues the uneven tenor of its way, sometimes laboring and plunging like a ship at sea, constantly heeling over at angles at which an upset seems unavoidable; now descending into the deep bed of a spruit, now sticking fast in heavy ground, now careering over masses of rocks and stones. The travelers, all shaken up inside like an omelet in a frying pan, never cease to wonder that the human frame can endure such a shaking, or that wood and iron can be so firmly riveted together as to stand such a strain.”

Then they visited the gold mines at Johannesburg including the Robinson Deep, the Langlaate and the Ferreira. The Boers in the Transvaal come in for harsh criticism; hotel accommodation “is of the roughest description, the Dutch scarcely appreciating either cleanliness or comfort” and later; “The Boer farmer personifies useless idleness. Occupying a farm of from six to ten thousand acres, he contents himself with raising a herd of a few hundred cattle, which are left almost entirely to the care of the natives whom he employs. It may be asserted, generally with truth, that he never plants a tree, never digs a well, never makes a road, and never grows a blade of corn. Rough and ready cultivation of the soil for mealies by the natives he to some extent permits, but agriculture and the agriculturist he holds alike in great contempt. He passes his day doing absolutely nothing beyond smoking and drinking coffee.”

On Sunday 12th July 1891 they reached Fort Tuli, the first day they spent of fourteen weeks exploring the country. From here they followed the route taken by the Pioneer Column through Fort Tuli and Fort Victoria (Masvingo) to Salisbury. “No hotels, no stores, no provisions to be bought on the road beyond mealies, and perhaps here and there milk and eggs and poultry.”

Their cooking efforts are described: “To collect brushwood and dried dung for the fire, to fill the kettles and boil the water are the first duties; bacon and eggs and bread are the staple of the repast, supplemented by such tinned provisions as may have been brought along.”

At Fort Tuli Sir Frederick Carrington, in command of the BSAP, Capt. Leonard and Major Tye arranged a demonstration of both the Maxim gun and the Gatling gun which were fired at 1,600 yards on targets in the Shashe riverbed. Then they tried a new magazine rifle Lord Randolph had brought along to test, using an ox as a target from 1,500 yards. The crack shot of the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) killed the ox on the twentieth shot; all present preferred the Martini-Henry rifle.

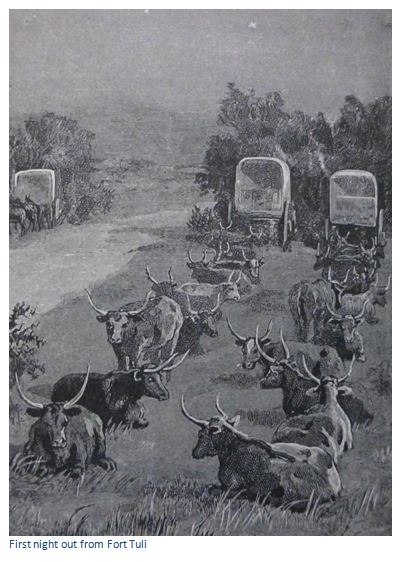

On the 17 July the exercise of crossing the Shashe River was carried out in exemplary fashion by Edgell and Mackay. “Here the sand is for more than one hundred yards is deep and heavy, and double spans become necessary for each waggon. The leading waggon having descended into the river-bed is halted, the span of oxen is taken out of the second waggon and attached to the first, which drawn by thirty-six oxen moves with apparent ease through the drift. This process, repeated with each waggon, occupied some two hours, and it was 4 o’clock before all the waggons were safely over on the other side.” [Actually the Shashe River is over 500 metres, 570 yards here]

Churchill says “the oxen come in in the evening from the veld in one great troop, driven along by their herders. They range themselves in spans, as schoolboys range themselves in classes, each span apparently knowing its own waggon, each ox its own place in the span…Our mule waggon, which loads over 2,000 lbs of transport, has a fine team of twelve mules. They are a most vicious set, and would readily bite or kick at anyone except Myberg, the conductor, or Gideon, the voorloper.”

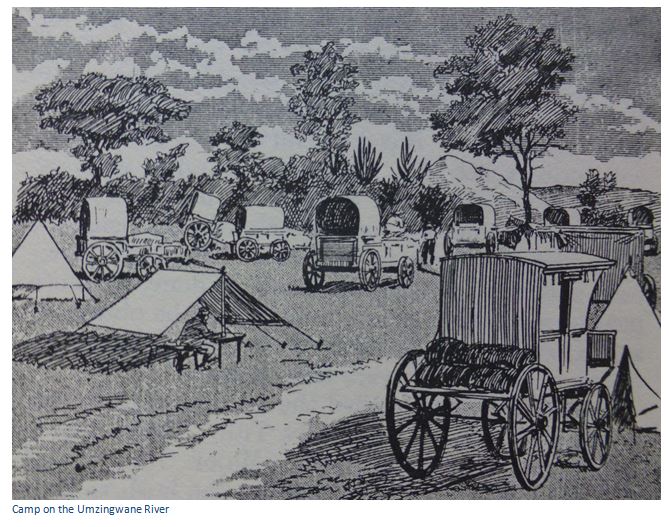

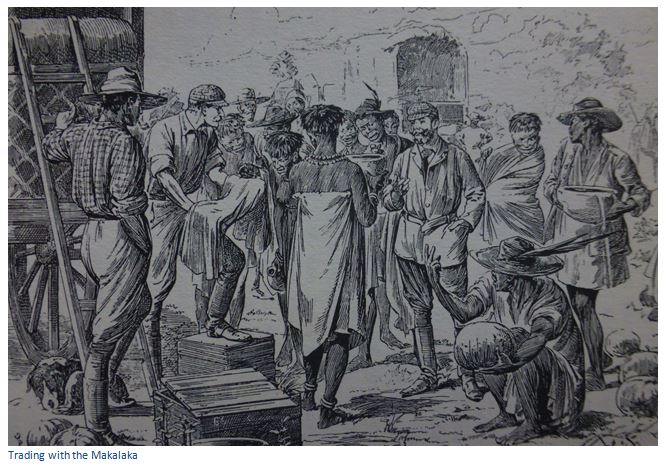

On the 19 July they reached the Umzingwane River and on the 21 July near the Bubye River Churchill “witnessed for the first time a regular native market. A small group of Makalaka had a kraal on the Umjinge River, close to our camp, and brought pumpkins, milk, mealies and beans, for which they took in exchange pieces of coarse blue calico “limbo.” Trade proceeded merrily with much laughter and joking…I found that one yard of “limbo” would purchase about a shillings worth of stuff.”

On 31 July they reached the Wanetse River (Nuanetsi) seventy metres wide with a strong current where the mule waggon stuck fast against a large boulder. All stripped and plunged into the stream where whips were applied, extra mules added and a jack placed under the waggon. “The mules struggled, plunged and tumbled about in the stream and on the rocks in an extraordinary manner, so that it was a wonder either that they were not drowned, or that they did not break some of their limbs” but to no avail. A team of twenty-two oxen were borrowed from a transport rider and they dragged the waggon up the opposite bank.

They passed the immense granite boulders that so intrigued Ellerton Fry during the passing of the Pioneer Column in August 1890 including the one called the Sugar Loaf. Unconnected from each other they rise almost sheer from the surrounding countryside.

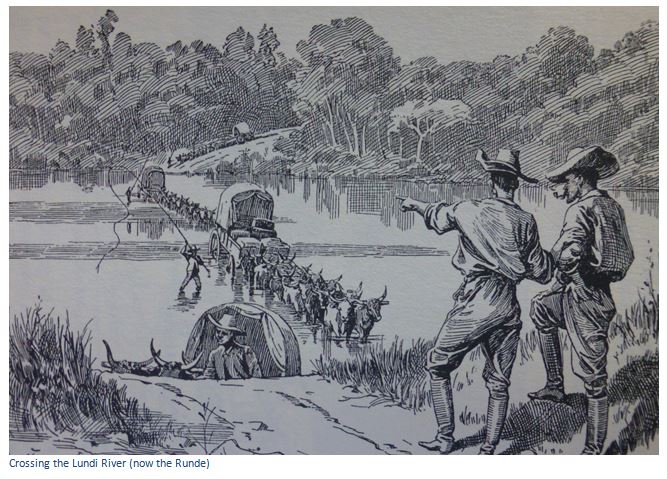

On 5 August they reached the Lundi River (Runde) and were reunited with Major Giles. The Runde is twice as wide as the Nuanetsi with good hard sand at the bottom of the drift and steep sides down to the drift from both banks. They wished to move on swiftly as the camping ground was a mass of dried and fresh dung from the masses of cattle that had waited for months during the rainy season. Churchill says the outspan had “a tainted and pestilential appearance” and fourteen graves lay within ten yards of the waggons. Travellers had arrived when the river was in flood and been kept here for weeks and sometimes months when they fell victim to malaria.

He neglects to say that they had accidents here both when they were inbound and outbound. Hans Sauer found the Churchill party encamped, just preparing to cross and describes the inbound incident which happened on the slope leading down to the Lundi River when the driver was too slow in applying the brakes. “The waggon consequently rushed down on the team, killing the wheelers and injuring some of the other oxen.” This was not the end of it and Hans Sauer continues: “By this time it was fairly dark. At the point at which we crossed, the river was divided into two streams by a small island over which the track passed. Lord Randolph’s second waggon got safely down to the bed of the river, but as the leading oxen reached the island we heard heart-rending screams from the voorlooper. Morkel and some of his men waded over to the island, where they found the unfortunate man had lost a leg, bitten off by a crocodile just as he reached the island. He succumbed before anything could be done to save him.”

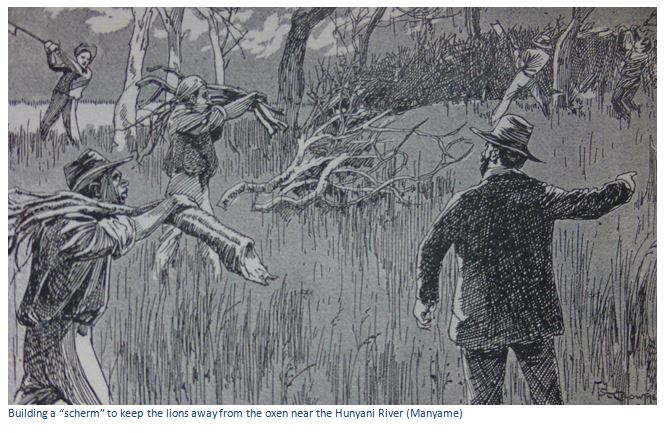

The Daily Graphic sketches seen here are from the artist’s imagination and do not reflect what actually happened. A number of the sketches are signed, but Churchill makes no reference in the text to the artists; presumably they are the unnamed Europeans that feature in the sketches of the expedition members.

He mentions Fly, a grey gelding being taken ill in the morning and despite being given quinine, gin and mustard poultices dying by sunset, then two oxen falling into deep spruits and breaking their necks with a mule dying next morning and then an ox. But no mention is made of the voorlooper’s death.

At Fern Spruit “Ruby”, a good horse, died in less than 3 hours, then his shooting pony “Charlie” was taken ill at midday and died in the afternoon followed by “Bless” one of their best horses, the next day.

He describes Providence Pass as nothing more than a long valley between hills slowly ascending from Fern Spruit to Fort Victoria and reached on 4 August and nothing remarkable. Just a “small square enclosure, protected by a mound, a ditch and a Maxim gun, and surrounded by a cluster of huts built of mud, reeds and grass, marks the rule of the British South Africa Chartered Company, and the site of what may one day be a populous and prosperous township. The Company at present maintain here a force of sixty-five police, commanded by Capt. Turner.”

The journey to Fort Charter took five and a half days which is described by Churchill as “an endless and most wearisome tract of barren sand, covered with dry, coarse grass, with stunted trees and bushes. No flowing river refreshes this expanse. Water there is in abundance, but of bad quality, lying in stagnant pools, slopping about in marshes and in swamps.” He complains that there are no mile-stones or posts to indicate the route, and this knowledge is impossible to obtain. “The natives who are met with have no idea of distance. Asked if a particular place or water is near, they raise the right arm, pointing it straight out to a level with the shoulder; if it is far, the arm is raised higher; if it is very far, then almost perpendicularly over the head.”

He states categorically; “the vast tract of country between Fort Victoria and Fort Charter is unsuitable and grievous either for man or for domestic beasts…the climate is capricious and variable. One day the heat is so great that it is difficult to support a flannel shirt; the next day a cold wind, driving rain or thick fog causes you to shiver in a great coat and muffler.” Near Fort Charter he met Colquhoun, the Civil Administrator, going down country who told him the gold fields near Hartley Hill and at Mazoe were expected to be excellent and Fort Salisbury was becoming quite a township, with a regular street of huts and tents, possessing two auctioneers.

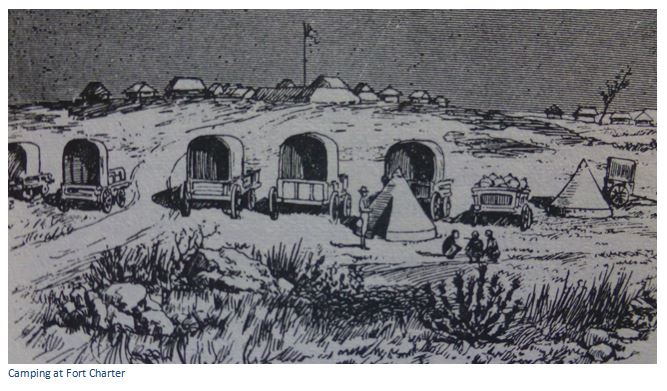

“The garrison at Fort Charter consisted of a lieutenant and twelve troopers, of whom ten were sick with various ailments.” Surgeon Rayner, a member of Churchill’s group, had lost his brother, H. Rayner, who died of fever at Fort Charter on 6 February 1891 and is buried in the small cemetery. [See Fort Charter article on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

“Both Fort Charter and Fort Victoria appeared to be miserably weak constructions, which a few thousand Matabele would probably rush with ease, attacking, as is their habit, in the dark just before daybreak. There is nothing to stop the rush of the savage foe, save a ditch from 3 to 4 feet deep, a mound from 10 to 12 feet high from the bottom of the ditch, and two or three strands of barbed wire stretched on weak posts.”

Leaving Fort Charter on the 13 August they reached the Umfuli River (Mupfure) on the 15 August travelling along the same heavy sandy road. “Stories of lions and of their audacity in attacking cattle outspanned at night were common along the road. Every waggon met with had its adventure with these beasts.” The party took precautions by keeping fires burning all night

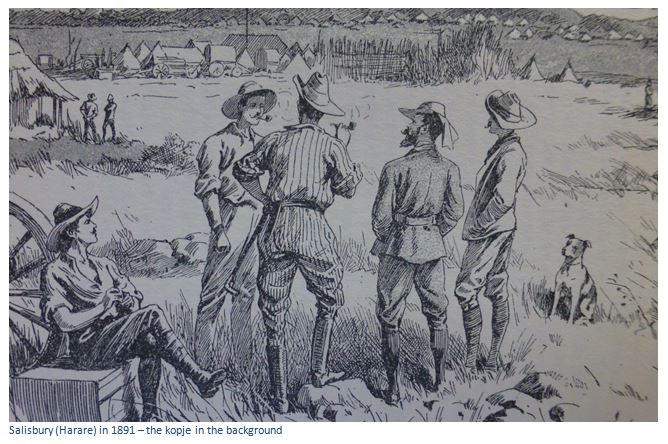

Soon after leaving the Mupfure River Churchill took the “spider” and left the waggons at their usual slow pace. Between 6am and 4pm on the 15 August they reached Fort Salisbury after covering fifty-six kilometres on an improved road.

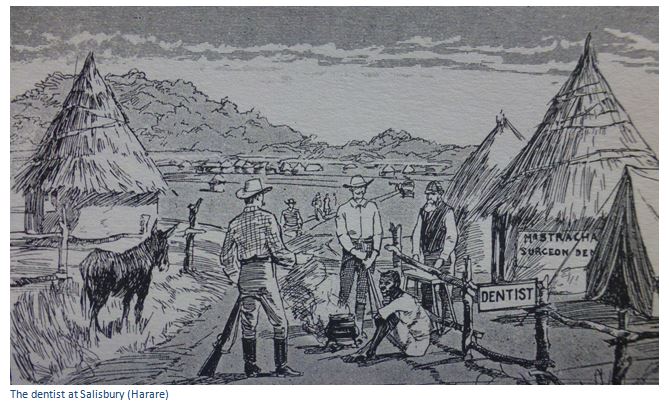

He describes Fort Salisbury as follows: “the settlement lies at the foot of and around a long kopje about three hundred feet high, thickly clothed with small trees. About half a mile to the eastward are the fort and surrounding huts, and again, half a mile further on, we find the civil lines, where reside Dr Jamieson, the civil administrator, and other officials of the company. Here I outspanned, and was very kindly accommodated with a hut by Sir John Willoughby. In this climate these huts give excellent shelter. Round, about sixteen feet in diameter, with sharply pitched conical roofs, built of poles and mud, and thatched with grass, they are warm at night and wondrously cool in the heat of the day. They can be erected by the natives in a week at a cost of from £10 to £12.”

Quite an imposing number of these huts, among which are interspersed waggons, carts, tents, shanties of every conceivable description, compose the settlement of Fort Salisbury, where resided from 500 to 800 persons. “In a walk around the settlement the next day, I noticed a hotel where was laid out a table d’Hote with clean napkins ensconced in glasses on the table, three auctioneers’ offices, several stores, the hut of a surgeon-dentist, another of a chemist, a third of a solicitor, and last, but not least among the many signs of civilisation, a tolerably smart perambulator.”

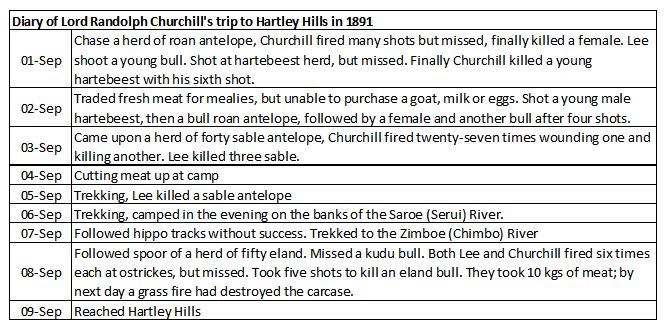

The next chapter after Fort Salisbury is all about sport in Mashonaland and indicates Lord Churchill’s real interests! There are hints to inexperienced sportsmen, the approximate cost of equipment for a six months hunting expedition, hunting the wildebeest, how to cook venison, method of scaring vultures off dead game. Presumably all these ideas were picked from experienced local hunters and Hans Lee.

A summary of Churchill’s diary shows a great many animals were killed, but that he was not a great shot.

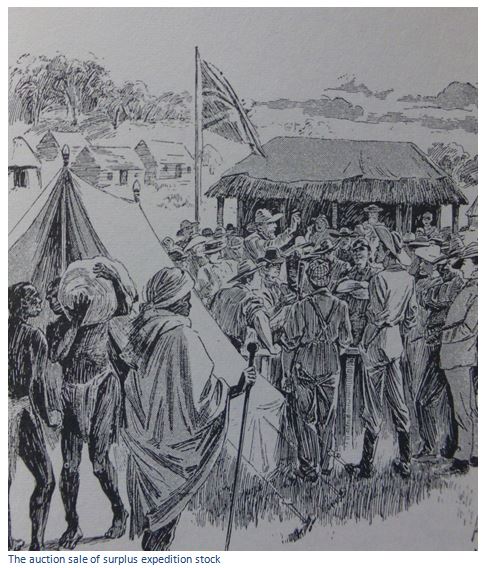

Following visits to the Mazoe and Hartley Hills goldfields, Lord Churchill surplus goods were sold at auction over four days, realizing £2,551; “the result of which was to me very satisfactory.” Martini-Henry and Winchester rifles went from £10 to £15, two dozen pint bottles of English ale and stout were sold at 3s. 6d. a bottle, brown sugar at 3s. a pound, butter at 11s. a pound, dried snook (fish costing 2d. a pound at the Cape) sold at 9s. a pound, cotton shirts (price in London 9s. 6d.) sold for 33s. There was great competition for red white-eyed beads which cost 6d. a pound in Kimberley and sold for 12s. a pound. “Limbo” the coarsest cotton material cost 1½ d. a yard, sold for 1s. a yard. No wonder the noble Lord was pleased with the result!

Presumably he used some of his auction proceeds on backing a horse which he had just sold and knew to possess a good turn of speed against a horse belonging to Rutherford Harris, the BSA Company Secretary, over a distance of five furlongs at the first horse race at Salisbury. Rutherford’s horse is described by Lord Churchill as a thick-set brown cob, pig fat, and he had little doubt which would win.

At 4pm he says three-quarters of the Salisbury population turned up for the race with the betting odds varying from six to four, to two to one on his opponent’s horse…which began to alarm Lord Churchill. Then to his horror his old horse appeared with “drooping head and ears, glassy eyes and tucked-up flanks!” Once the race started, his flyer which he had previously tipped to win, tried to canter for fifty yards, and then slackened to a slow trot, until finally Harris’ horse cantered past the winning post alone! Lord Churchill calls this episode an odd business, but it appears his steed was “got at” in the stables.

On the 20 October Lord Churchill said goodbye to Salisbury. He complained bitterly about the state of the road between Fort Charter and Fort Victoria saying “the protruding tree-stumps, huge rocks and ant-heaps were a constant source of danger” and suggests that the BSAP were well qualified to make and repair roads. Indeed, he really lays into the Police saying that they do not keep their forts and military lines clean, their construction to date of forts and dwellings has been pitiable, showing neither design, skill, nor solidity! They have no military drill or training, no shooting instruction. He concedes that the Police did a good service routing the Portuguese near Mass-Kessi, but the spasmodic energy of a few does not excuse the normal sluggishness and uselessness of the many!

Near Fort Victoria they met the members of the Pieter Lourens van der Byl trek who came up from the Cape and settled near Rusape. Sadly their leader died of malaria and was buried at Mona Farm; the others lost enthusiasm and dispersed and the experiment ended in failure. [See the article under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The telegraph line was then just two miles from Fort Victoria and the drawing shows Rhodes and Lord Churchill sending off messages they have written on the dϋsselboom of the telegraph waggon to Cape Town and London.

Having lost three horses at Fern Spruit on the way up to horse sickness, he lost another at Wanetse River (Nuanetsi) which had been sold as a “salted horse” at Fort Victoria for a comparatively large sum. An ox- waggon came to grief in the dark on crossing a nasty spruit shortly after the Lundi River and completely overturned.

They reached Fort Tuli where Lord Churchill says: “some 200 men of the Chartered Company’s Police [BSAP] are now here, but it would be difficult to determine what useful occupation they are engaged in.” Major Giles brought his ox-waggon into Fort Tuli in the early morning of 6 November, a best on record and covered the distance from Fort Victoria in seven days doing twenty-nine miles a day. So well were the oxen looking that Lord Churchill was very pleased to sell the whole span here for £8 a head.

From Fort Tuli they travelled to Macloutsie and then to Palapye, the home of Khama, and from there to Mafeking and finally to Vryburg; “where waggons, tents, “boys,” naked savages, will all be forsaken for comfortable railway carriages, civilized hotels, daily newspapers.”

Syphilis or Brain Tumor?

The text below is by J.H. Mather MD who wrote an article entitled; ”In Search of Lord Randolph Churchill’s Purported Syphilis.” He wrotes: A cardinal feature of advanced syphilis is a dementia (confusion) and muddled thought processes. While Lord Randolph had some difficulty articulating words (expressive aphasia) he had virtually no problem with writing down his thoughts. Muddled thoughts, memory lapses and profound confusion—all features of advanced syphilis—were absent from Randolph’s writings almost until his death. He wrote more lengthily, and his script became shaky, but it was never unintelligible. Until the last, when he was in a coma, his writings were rational. They include a cogent, thoughtful letter to Winston while on his world tour in August 1894.

After further study of Lord Randolph’s symptoms and rapid deterioration, I concluded as follows: While the diagnosis of advanced syphilis is possible, the cause of his condition was far likelier to have been a brain tumor.

About a decade ago a Lady Randolph biographer asked a neurologist from Kings College Medical School to review Dr. Buzzard’s medical records. He told me that all they revealed was that Randolph had a chronic progressive neuro-degenerative disease of the brain. He did not specifically rule out syphilis, but considered that it unlikely. Jennie, Winston and Jack, he observed, never suffered syphilis.

Acknowledgements

R.S. Churchill. Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa. Books of Rhodesia No 7, 1969

H. Sauer. Ex Africa. Books of Rhodesia no 27, 1973

https://winstonchurchill.hillsdale.edu/in-search-of-lord-randolph-churchills-purported-syphilis/