Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and Cemetery

This area played a very significant part in the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga as a centre of resistance because of the importance of the Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe – Gumboreshumba Kaguvi strategic alliance. It was Kaguvi who supplied the spiritual encouragement for Chiefs Mashayamombe, Chikwakwa, Seki, Kunzwi, Mangwendi and others to maintain their resistance.

The tactics that had served the Mashona against amaNdebele raiders in the previous fifty years, retreating to the caves with their families and hiding their cattle until the enemy left the area, served them well against the European military. The seven-pounder and Maxim gun were rendered ineffectual and the older muskets caused significant casualties when used at close range from within the caves.

The significant dates are as follows:

14 June 1896 the very first killings of the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga take place near Mashayamombe’s kraal of Indian traders near the south bank of the Mupfure River. Next day, the first European David Mooney, the Native Commissioner, is killed and separately so are two prospectors, John Stunt and A. Shell.

Twelve prospectors and traders fortify Fort Hill at Hartley Hills and are sniped at by Chief Mashayamombe’s men from 18 June.

On 19 June Capt. PA Turner and the Natal Troop (50 men) come from Beatrice and attempt to attack Mashayamombe’s kraal, but are forced to turn back after suffering stiff resistance.

22 July 1896 the siege of Fort Hill at Hartley Hills is ended by Capt. the Hon. C.J. White.

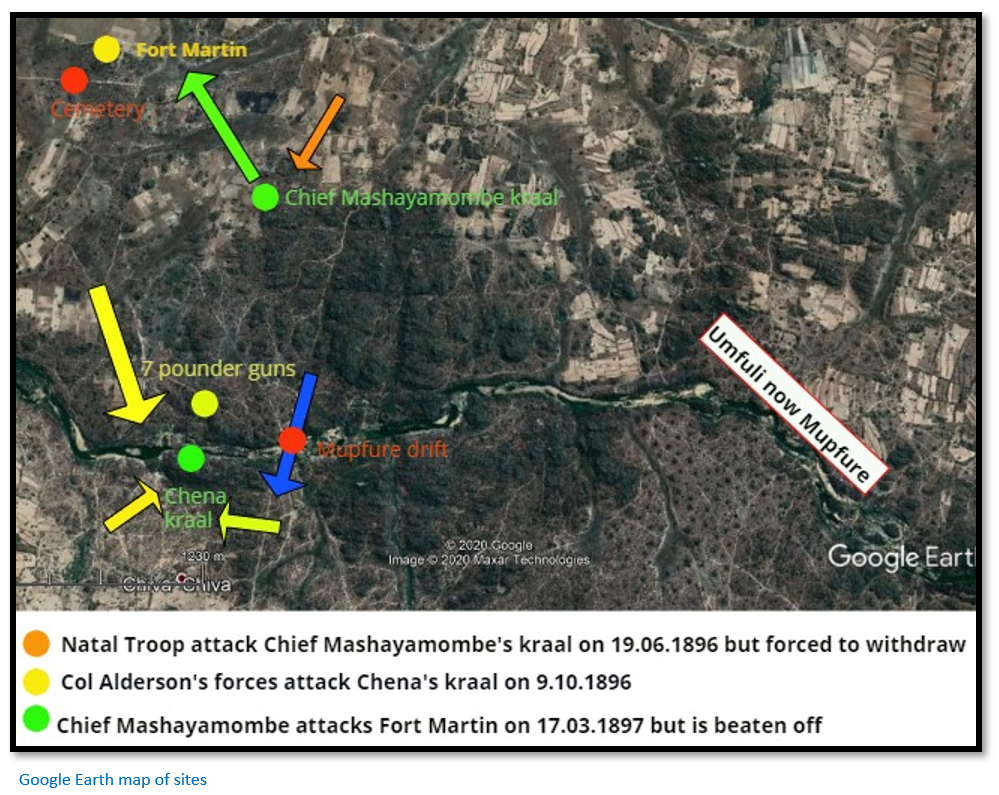

9 October 1896 Col. EAH Alderson and Major Jenner’s forces attack Mashayamombe’s kraal, and Chena’s kraal on the eastern side of Kaguvi Hill. They overran the complex of caves, burnt the kraals and seized cattle, but finally withdrew after three days. The Mashona forces reoccupied their kraals and saw the inconclusive result as a victory for themselves.

Fort Mhondoro, on the south side of the Mupfure, was built on 13 January, but abandoned by 12 March 1897.

Fort Martin, within one and a half kilometres of Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal, was occupied by the BSAP under Capt. RC Nesbitt on 20 March 1897; operations began to disrupt crop planting.

Chief Mashayamombe was forced to attack Fort Martin with 300-400 men on 17 March 1897, but was driven off.

1897 Chief Mashayamombe's stronghold in the kopje’s behind his burnt out kraal was attacked on 24 July by local forces under the BSAP and led by Inspectors Nesbitt and Harding and Lt-Col. de Moleyns and taken after stiff opposition. The defenders retreated into a large cave, but were blockaded with and surrendered next day. Chief Mashayamombe’s fate is unclear, but he may have been killed on the first day of fighting.

Fort Martin was abandoned the following year.

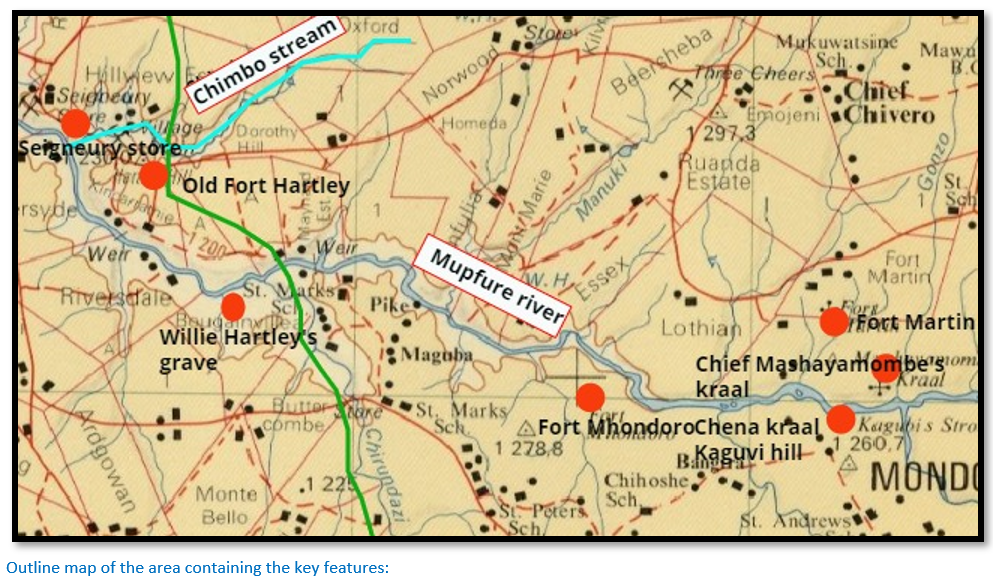

The general area is easily reached from the main Harare Bulawayo A5 National road 71 KM from Harare, by turning left off the National road at the Selous roundabout, south toward Ngezi Mine. At 7.2 KM continue past Chengeta Safari Lodge turnoff on the left and at 15.73 KM reach Seigneury Road intersection. Turn left onto the gravel road, 17.54 KM reach the Seigneury store.

Distances for Fort Martin are from Seigneury Store. Continue east and cross the Chimbo Stream. At 16.8 KM pass the Three Cheers gold mine on the right, at 17.8 KM reach Emojeni Store and turn right, heading south. At 23.7 KM turn left off the current road heading east. At 26.0 KM turn right heading south for 0.5 KM, but before the farmhouse at 26.5 KM turn left onto a farm track. At 27.2 KM cross a vlei, at 28.0 KM reach Fort Martin cemetery on the left and park here.

For Fort Martin continue east another 90 metres and then walk north up a farm track for 100 metres before going right towards the kopje. A faint path leads another 100 metres towards Fort Martin.

For Mashayamombe’s kraal continue east from the cemetery for 450 metres and then turn right down a track and cross the vlei. At 0.9 KM turn left towards the kopje and follow the track for another 600 metres.

The gun position for attack on Chena’s kraal is slightly west of a small kopje, 300 metres from Chena’s kraal across the Mupfure River.

GPS reference for Fort Martin: 18⁰14′17.28″S 30⁰33′39.84″E

GPS reference for Fort Martin Cemetery: 18⁰14′20.50″S 30⁰33′31.63″E

GPS reference for Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal: 18⁰14′42.35″S 30⁰34′13.10″E

GPS reference for Mupfure River drift: 18⁰15′34.94″S 30⁰34′21.67″E

GPS reference for gun position for attack on Chena’s kraal: 18⁰15′26.92″S 30⁰34′03.54″E

GPS reference for Chena’s kraal: 18⁰15′36.82″S 30⁰34′00.28″E

GPS reference for Svikiro Cave on Kaguvi Hill: 18⁰15′38.52″S 30⁰34′04.52″E

Note: only Fort Martin and the cemetery have been visited at this time, the other sites will be visited once the rainy season is over.

Outline of the Mashona Rebellion 1896-1897 - The First Shona 'Chimurenga'

The Mashona Rebellion / First Chimurenga came as a surprise, despite the ongoing Matabele crisis in the west of the country. The settlers saw the Mashona as farmers, fragmented into a number of autonomous chieftainships, owing allegiance to no single authority, nor were they organised in any way along the scale of the Matabele regiments under Lobengula.

But Mashona resentment had grown at being subjugated by their newly imposed rulers who had taken their land, coerced them into the workforce, introduced forms of taxation (hut tax), which they had resisted, and had usurped the authority of their Chiefs. Evidently, the same problems that afflicted the Matabele, rinderpest, drought and locusts, also played a role.

On 17 March Matshayangombi launched an attack on Fort Martin (in the Charge of Captain Nesbitt), but was beaten off after a fierce three hour battle. On 1 April Chief Umzililemi apparently surrendered in the Charter area, but at Svosve, in the same area, rebels attacked a patrol resulting in raids on several kraals that were relieved of their food supplies. A Fort was established at Lomagundi as the police influence spread. Kunzwe's Kraal was attack on 19 June as was Mashanganika's Kraal.

On 24 July there had been a decisive attack on Mashayamombe's Kraal conducted by the police, ably assisted by the 7 Hussars troop, who had been left in the country after Lieut-Col Alderson's departure. During this offensive the Chief was killed, although some sources indicate he may have escaped with Kaguvi and Mkwati who travelled to the Makoli Mountains, then Chipolilo and eventually sought refuge with Mbuya Nehanda, a powerful and influential female medium in the Mazoe Valley. Nehanda Charwe Nyakasikana, as she was known, was considered to be the female incarnation of the oracle spirit Nyamhika Nehanda (daughter of Motota the first Monomotapa). Her role in the rebellion was significant, if not more so, than that of Mkwati and Kaguvi, 'blooding her spear' when she ordered the killing of Pollard, a Native Commissioner. He had been resented by her people for having thrashed Chief Chiweshe who had failed to report an outbreak of Rinderpest.

Chief Zvimba surrendered on 21 August as did Chief Mangwende, of Mrewa, on 2 September, he being the last significant Chief to succumb to the authorities during the rebellion. The spirit medium Kaguvi also eventually surrendered to the Native Commissioner at Mazoe on 27 October 1897. He had attempted to influence Mbuya Nehanda to surrender with him, but she refused. She was arrested before the year was out. What became of Mkwati is uncertain, but there is reference to his having been murdered by the Shona during the latter course of the rebellion. Kaguvi's arrest marked the end of the rebellion, and for his part he faced trial with his sister medium in 1898; both were sentenced to death by hanging and so ended what the Shona regard as their first Chimurenga.

The new offensive concentrated on the establishment of forts in those areas where rebellion still festered, rather than along principal communication routes. Fort Martin was established near Mashayamombe's Kraal and Fort Harding was set up near Chikwakwa's Kraal amongst others. The tactic of using dynamite to blast cave fugitives into submission is increasingly evident. In January police elements raided Manyese's Kraal, Sekki's Kraal was overun and a Fort was established at Gondo's Kraal, which was assaulted on 16 February. Chinamora and Makombi's Kraals suffered similar fates on 1 March.

Background

The late Dr D.N. Beach, in an excellent article that helps balance the predominately Eurocentric writing of the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga, states that before 1893 there were reasonably good relations between the newly arrived Europeans and the local Mashayamombe and Chivero chiefdoms. However, after 1893 the British South Africa (BSA) Company assumed they had inherited the amaNdebele dominance over the Mashona and began to tax the people.

Local hut tax collection began in 1894 under the Mining Commissioner at Hartley, but was not a success, and in the following year the responsibility for hut tax collection was given to H. Thurgood, a local Hartley trader. D.E. Mooney an ex-Corporal in the King Williamstown Police was initially responsible for the recruitment of labour and significantly, a Native Department station was set up close to Chief Mashayamombe’s village. After 12 September 1895 he succeeded Thurgood as hut tax Collector; but from 20 December this position was given a new title, that of Native Commissioner.

Both were thorny issues; increased mining activity was leading to a demand for labour that was not satisfied by local volunteers or migrant labourers from Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique. As a consequence, local people were often forced to work for low pay and this was enforced by rough methods, the labour system being called “chibaro.”

However much that this was resented by local people in 1894 – 1895 there was little that they could do about it until the botched Jameson Raid of 29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896 had taken place and left the entire country without an effective Police force.

Early in April 1896 and shortly after the Matabele Rebellion had broken out, Gumboreshumba the Kaguvi medium, who was organising the rising of the Shona people against the Europeans, had visited Chief Mashayamombe. Historically, there had been a close connection with the area as the grandfather of Gumboreshumba, Kawodza, had lived at Kaguvi Hill on the south bank of the Mupfure River. Dry-stone walling had protected Kaguvi Hill from AmaNdebele raiders. At the summit of Kaguvi Hill is a cave and natural stone seat which was used by the Kaguvi spirit mediums, and below is Kaguvi Pool on the Mupfure River which apparently never dries up, and so the area attained a religious symbolism

Traditionally, Shona religious figures do not get involved in fighting and must be protected by their relatives, but Kawodza was killed at Kaguvi Hill and his son Chingonga and grandchildren, Gumboreshumba and Makuwatsine moved from the area to the Chinamhora chiefdom, north east of Salisbury. In the late 1880’s when Gumboreshumba became possessed by the Kaguvi Mhondoro, he moved back to the family’s traditional home north of Chief Mashayamombe and near Chief Chivero on the south road between Hartley and Salisbury, called Mupfumera’s.

Chief Mashayamombe and Gumboreshumba had a falling out as the Chief received medicine from the Mlimo in the Matobo Hills and demanded payment of a cow before he would supply any to Gumboreshumba. Gumboreshumba then sent his own men to the Mlimo who were informed that the Mlimo was a God and could kill all the whites and that Gumboreshumba Kaguvi would get the same powers and should kill all the whites in Mashonaland.

The Native Commissioner of Hartley, David Mooney, had established his camp close to the village of Muzhuzha Gobvu, a nephew of Chief Mashayamombe. On 24 May 1896, Mooney reported to the Chief Native Commissioner, W.S. Taberer; “Sir, whilst out collecting tax I discovered that a good many Matabele have left Mashayingombi’s district for Matabeleland for what object, I can’t find out. I also heard from one of my spies that Mashayingombi himself is in communication with someone in Matabeleland, and has lately sent some young men down. I taxed Mashayingombi with this, but he informed me that he had only sent down to the Matabele “Umlimo” for some medicines to prevent the locusts from eating his crops next year. This spy also told me that that it had been proposed by the Matabele and Maholi inhabitants to rise and first kill all my Police and the “coolie” that is trading, and then try Hartley, but it was given up as not good enough. I attach no importance whatsoever to the above, I find the natives very quiet and civil when I go to their…”

Tensions had begun to grow between Mooney’s men and those at the nearby village of Muzhuzha Gobvu. Three days before Mooney was killed, Muzhuzha beat the wife of Jim, one of Mooney’s men and when the women complained, Mooney thrashed Muzhuzha. Four men from Muzhuzha’s kraal then ran out with guns which Mooney confiscated and sent to Thurgood at Hartley. Mooney then crossed the Mupfure River to the south bank and found the bodies of several Indian traders killed at their store, probably on 14 June 1896; on their return to Mooney’s camp a number of his men deserted.

Next day, Jarivau (named January in the BSA Company Reports) went up to his wife’s hut at Muzhuzha’s kraal and saw Chief Mashayamombe’s armed followers, led by his brother Chifamba coming towards Mooney’s camp. When warned, Mooney realised that his flogging of the Chief’s nephew Muzhuzha and his men’s desertions were connected. He quickly mounted his horse and rode towards Hartley Hills with his remaining men. Just past the Nyamachene River, his horse was wounded and Mooney climbed a small kopje and was killed here in the ensuing gun battle.

His messenger Jarivau managed to escape and from a cave watched two traders, Stunt and Shell, walk into Muzhuzha’s kraal, where one was shot and the other ran off before being stabbed and both their bodies were thrown into the Mupfure River. Jarivau then made his way 20 kilometres west to Fort Hill and informed the men there of the tragedy. On hearing this news, all but two of the African servants at Fort Hill deserted. [For additional detail read the article Fort Hill and the Cemetery at Hartley Hills goldfield on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Chief Mashayamombe’s men now went on the offensive. The Chief’s nephew, Kakono, travelled over sixty kilometres west to the Umsweswe River to kill JC Hepworth and another group under the Chief’s brother, Chifamba Muchena, went east to the Beatrice Mine and killed Tate, Koefoed and four of their workers.

When news of the outbreak reached the prospectors and traders at Hartley Hills, twelve of the thirty-four resident decided to stay and protect their properties and stores, and fortified the hill which had previously been occupied by Graham the Mining Commissioner. Little did they know at the time, but one of the main centres of the rebellion was only twenty kilometres away at Mashayamombe’s Kraal.

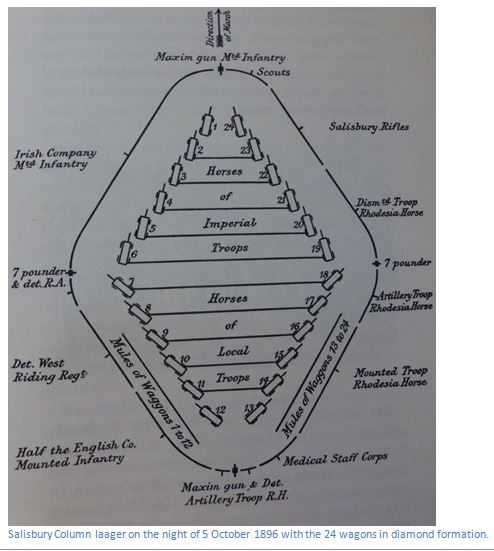

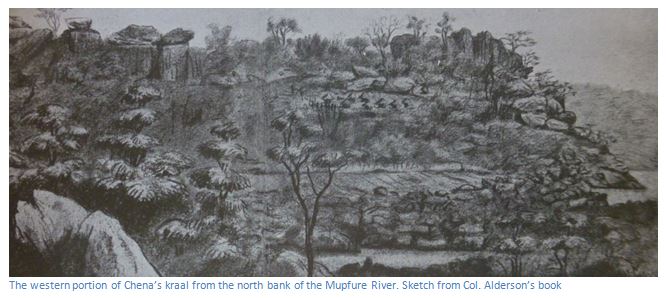

Mashayamombe’s stronghold on the north bank of the Mupfure River presented a significant military challenge with granite boulders piled up on top of each other and provided plenty of protection in numerous caves and hiding places which had been reinforced with sections of dry-stone walling. The pole and dhaka huts were built under the kopjes and had offered a refuge from the amaNdebele who were accustomed to sending annual raiding parties into Mashonaland. The industrious Mashona worked their gardens in the vleis which stretched down into the small tributaries feeding into the Mupfure River and grew millet, mealies, sweet potatoes, pumpkins and nuts; rice being grown in the wetter areas.

On 18 June a patrol of the Natal Troop numbering thirty-six and eight men of the Umtali Contingent under Capt. P.A. Turner on their way to Matabeleland were recalled from Charter to investigate the Beatrice killings. At the Mupfure River drift they met a small force under Lieut. Christison with a sergeant and four men and a Maxim gun and the combined force of 50 burnt the nearby Chifamba Muchena’s village, but met increasingly heavy opposition as they moved west up the south bank of the Mupfure. They reached the store and drift at Kaguvi’s Pool on 19 June, but turned back on the 22 June having lost Trooper JB Mitchell of the Umtali Contingent who was fatally wounded and died on 27 June, Surgeon Lieut. Gray, Trooper Finucane and Sergeant Snodgrass were wounded and eleven horses killed, one lost and three wounded.

Chief Mashayamombe’s men surrounded Fort Hill and prevented any communication between Hartley Hills and Salisbury, until the siege was relieved by a patrol under Captain the Hon. C.J. White on July 22nd and Fort Hill was abandoned.

In August a force of 380 regular troops, named the Mounted Infantry under the command of Lt.-Col. E. A. H. Alderson, landed at Beira and pushed on towards Salisbury, defeating Chief Makoni, and having several other engagements on the way. They were specially trained mounted infantry, accompanied by engineer and artillery detachments, and various volunteer units, including Honey's Scouts. They reached Salisbury on the 9 August 1896, and were immediately engaged in sending patrols out in Mashonaland.

The Hartley Hills district was virtually abandoned, with only one patrol under Lieut. Pilson of the Mounted Infantry, together with Rhodesian volunteers, and a Zulu contingent, operating in the area of Norton's Farm, from September the 17th to 24th. They had two skirmishes, and returned with a small number of livestock and 10 wagon loads of grain and burned several kraals according to the official report. They had a mounted infantryman wounded at William's kraal and one of the Zulu contingent killed.

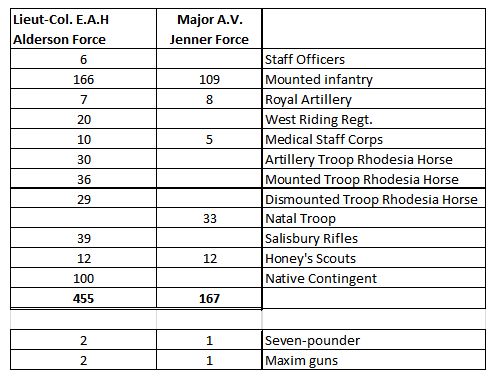

An assault on Chief Mashayamombe had long been deferred due to a scarcity of food for both troops and fodder for the horses and oxen; but on 5 October a force of 355 Europeans and 100 African troops, two Maxim guns and two seven-pounders with 14 days rations (there was not enough to supply more) left Salisbury to attack Chief Mashayamombe’s stronghold. The make-up of the force is tabled below:

The column laagered that evening 7 kilometres from Salisbury in the diamond-shape shown below, the horses within the laager and the men sleeping on the outside. Next day they crossed the Hunyani River (now the Manyame) with most of the wagons being double spanned to get them through the drift; this drift is now under Lake Chivero. On the 7 October they reached the Serui River and on 8 October reached the Chimbo River at Hartley Hills. Going east they laagered on the 9 October about 5 kilometres west of Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal.

A flanking movement had been planned with Major AV Jenner leaving Fort Charter with a force of 167 Europeans, one Maxim gun and one seven-pounder and attacking from the south to drive the Mashona from their kraals on to Mashayamombe's.

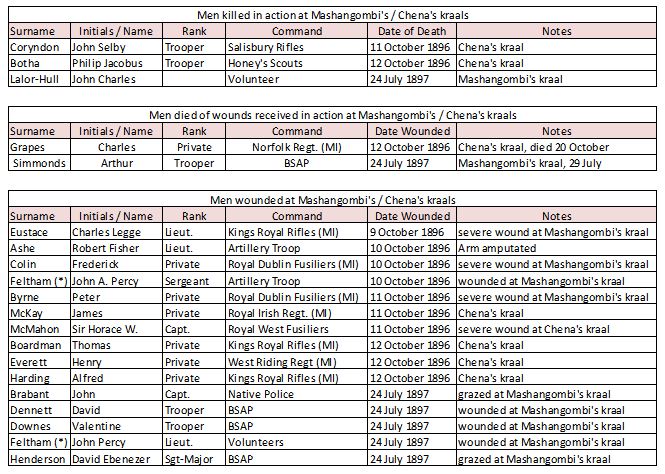

On the night of 9 October Jenner and Alderson made contact by signal rockets with Alderson to the west and Jenner to the east of Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal. The Mounted Infantry, the Salisbury Rifles and the Native Contingent were sent to attack Mashayamombe's main kraal and when his men retreated into the kopjes, dynamite was used to drive them out of the caves in stiff fighting in which three of Alderson's men [Lieut. Ashe, Private Colin, Sgt. Feltham] were wounded. The two forces joined up and a number of kraals were burnt down and amaNdebele shields, head-dresses and assegais captured.

Col. Alderson mentions a brave act by Colin Harding, who rescued a blind Mashona child who was crying inside a cave, just before the cave itself was assaulted.

The following day, 11 October, the strongly fortified Chena’s kraal on the south bank of the Mupfure River was shelled by artillery and attacked by McMahon’s men; the Mashona defenders again taking refuge in the caves. In this action Tpr. John Selby Coryndon of the Salisbury Rifles was killed; Coryndon was the brother of Sir Robert Coryndon, who later became Administrator of Northwest Rhodesia, and later Governor of Kenya. Capt. Sir Horace McMahon of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, two other Europeans (Byrne and McKay) and two members of the African Police were wounded. Cattle were captured and kraals burnt, but Alderson thought few Mashona were harmed as they took refuge in the extensive cave network within the kopjes.

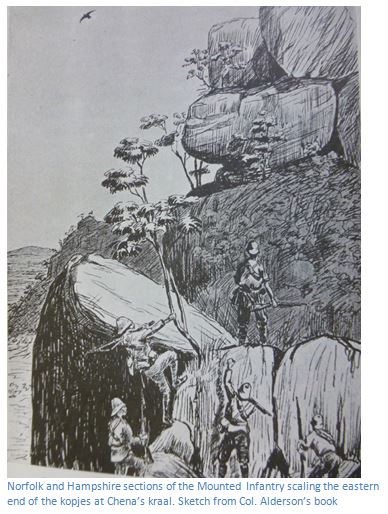

Next day 12 October, Jenner’s Rifle and Irish Companies of the Mounted Infantry crossed the Mupfure River at the drift to the east and moved south of Chena’s kraal. Alderson’s Natal Troop and Rhodesia Horse crossed where the Mupfure was fordable to the west. The Mounted Infantry carried out the assault with the Natal Troop in reserve and the Rhodesia Horse guarding the horses.

The reserve forces got into position on the north bank of the Mupfure with the seven-pounders and once in position they opened up a heavy fire. After a pre-arranged ten minutes, they ceased fire and the Mounted Infantry who had been under cover climbed into the kopjes on the south side of Chena’s kraal. They came under heavy fire from a line of kopjes to their right and a section was detached to meet this flank fire.

The remainder of the two companies advanced into the kopjes before occupying Chena’s kraal and setting it on fire. Tpr. PJ Botha was killed and Private C Grapes mortally wounded in the assault; Privates T Boardman, H Everett and A Harding were wounded and two African Troops killed. Many Mashona now ran down to the south bank of the Mupfure River where they were fired upon by the troops on the north bank and scattered.

Private C Grapes was mortally wounded by a “family gun” thrust up through a crevice in the rocks and died of his wounds eight days later. The African forces under Capt. Brabant then were sent in to clear Chena’s kraal and some caves dynamited.

Alderson did not think this action was particularly decisive as Mashayamombe’s forces scattered and disappeared and he had insufficient supplies to build and fortify a fort on the north bank. The entire force had only been sent out with 14 days rations and once the rains begun it was quite common for wagons to be held up for three weeks at the Hunyani River. That night he consulted Arthur Eyre and Capt. Brabant who considered that most of the Mashona fighting men would now have left the district and the best policy would be to return to Salisbury.

In reality, most of Mashayamombe’s men had simply moved to other strong points and caves and re-emerged after the attacks, Chief Mashayamombe’s people settled down to plant their gardens before the rains came. Little militarily had been achieved and Mashayamombe’s resistance had certainly not been broken as he now believed he could hold out in his kopje stronghold.

Alderson was criticised for his effort for not establishing permanent forts. Earl Grey, the Administrator of Rhodesia between 1896-1897 said: "Alderson and his mounted infantry made so rapid a promenade militaire through the country that in many places the result is nil and the natives are in a state of mutiny. Alderson committed two blunders, after his third attack on Mashiangombie he should have blown up the cave and left a fort behind. He did neither and the result is that Mashiangombie believes we are afraid and impotent." Other criticisms were made because no “thorough punishment” had been imposed on the rebellious Chiefs, except for Chief Makoni; those responsible for the killings of civilians had not been arrested, and the spirit mediums Mbuya Nehanda and Kaguvi had not been brought to trial.

These criticisms fail to recognize Alderson’s lack of supplies and the local forces’ lack of operational military intelligence which failed to inform Alderson of the importance of the Mashayamombe – Kaguvi strategic alliance to the uprising as a centre of resistance. It was Kaguvi who supplied the spiritual encouragement for Chiefs Mashayamombe, Chikwakwa, Seki, Kunzwi, Mangwendi and others to maintain their resistance.

Alderson was well aware of the defects in his military campaign and wrote from Lomagundi on 23 October: “I have plenty of men to go into any two districts at the same time and drive the rebels out of these, but I have not enough to establish strong posts in two or three districts and still be in a position to effectively clear others. In my opinion posts are absolutely necessary; what happens now is as follows. A patrol goes into one district and breaks up the rebels in it; they then go into another, the patrol follows, and the rebels then go further on and eventually return behind the patrol into their original district. When each district has been harried by a patrol, I consider that a post should be established of from 50 to 75 men according to the size of the district and the number of natives in it. These posts should constantly patrol and neither allow the natives to sow, or reap, or graze their cattle. This appears police rather than military work, and I do not think that a sufficient number of the present local forces would be willing to do it through the present wet season. It would be necessary to give many of the posts, one being that at Hartley, supplies for four months as wagons would not get to there during the wet season.”

On 9 December, Capts. Perry and Brabant reoccupied Fort Hill at Hartley Hills with a garrison of 80 BSAP. Peter Garlake quotes their orders as: "to make frequent patrols especially after arrival to show we are in possession, to encourage the friendlies, but not to provoke hostilities" and Earl Grey commented: "Alderson has left an inheritance of difficulty for us to deal with. If you remember the first thing I did after my arrival at Salisbury [November 18th, 1896] on finding out that no fort had been established at Hartley was to get Alderson to send out a force at once and establish one and after some little difficulty I got him to do so. Well, the evidence which this fort gives that we intend to stay there is puzzling Mashiangombie and is already beginning to make him uncomfortable— the latest news is that he is quarrelling with the Mondoro Kagubi, the main leader of the entire Mashona rising, who had his headquarters at this kraal and who has taken some of his wives. I have every hope that we shall be able, without taking any active measures against his kopjes, to reduce him to the state of submission which is necessary if the country is to be safe for the miner."

Faced with the onset of the rainy season making large scale military operations difficult and encouraged by the success of the Indabas with the amaNdebele, negotiations were begun with Chief Mashayamombe. However he dragged the negotiations out and soon the European administration began to realize the impact that Gumboreshumba, the Kaguvi Mhondoro spirit medium had on encouraging local resistance.

On 9 December Chief Native Commissioner Taberer, de Moleyns, Brabant and the Hon. H. Howard, Earl Grey’s private secretary, visited Mashayamombe for discussions. They learnt that a further quarrel had taken place between Gumboreshumba and the Chief. It had always been a mark of respect that young girls had been offered to mediums as servants, rather than wives, but Chief Mashayamombe neglected to do this, and Gumboreshumba seized some of his women. This resulted in fighting in which two of Gumboreshumba’s men were killed and a state of hostility now existed between the two.

Taberer took advantage of this situation by telling Chief Mashayamombe that he would be left alone and they would deal with Gumboreshumba. He asked de Moleyns to capture or kill the Mhondoro spirit medium.

On 12 January 1897 de Moleyns left Hartley Hills with 186 men to make a night attack on Chena’s kraal, but failed to achieve a surprise attack. He reported: ”the early part of the march while the moon was up was easy, but after midnight the darkness was extreme and it was very difficult to keep in touch in the thick bush, but at 3am I reached a point about one mile west of the Mandora’s kraal with all my force. I was informed by spies sent on by Captain Brabant that the natives were awake, occasionally firing off guns and had men on the lookout. Under the circumstances I considered that even if I could effect an entrance into the kraals it was doubtful whether I could capture the Mandoro, I decided not to make the attempt. I allowed the men to sleep until daylight, 13th, and then…reconnoitred the country round Mandoro’s kraal and selected a position for a fort, where I established myself, distance 9 miles ESE of Hartley, 1 mile from the Umfuli, and about 4 miles from the Mandoro’s. The fort [Fort Mhondoro] is on a kopje rather too extensive for the force that I can leave here, but excellently situate for harassing operations and capable of good defence.”

Earl Grey’s comments were again critical: "de Moleyns again was irresolute, made a night march to within a mile of the enemy and then right about to build a fort instead of instantly putting the matter to the torch."

On 17 January de Moleyns men attacked Kaguvi’s Hill, but their target had fled. Next day, two of Chief Mashayamombe’s messengers arrived at Fort Mhondoro to say that Gumboreshumba, the Mhondoro spirit medium, had left the district for the Chinamhora area where he continued to lead the resistance.

Fort Mhondoro, like Fort Hill at Hartley Hills, was extremely unhealthy and fever-ridden. It had a very short history; established on 13 January 1897, two attacks were made on the fort on 8 and 10 February and beaten off. However, with the spirit medium’s departure, the need for a fort on the south side of the Mupfure River was gone, and it was abandoned on 12 March by its garrison of 24 men.

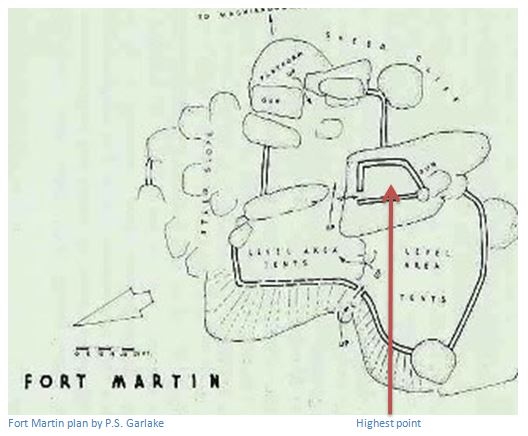

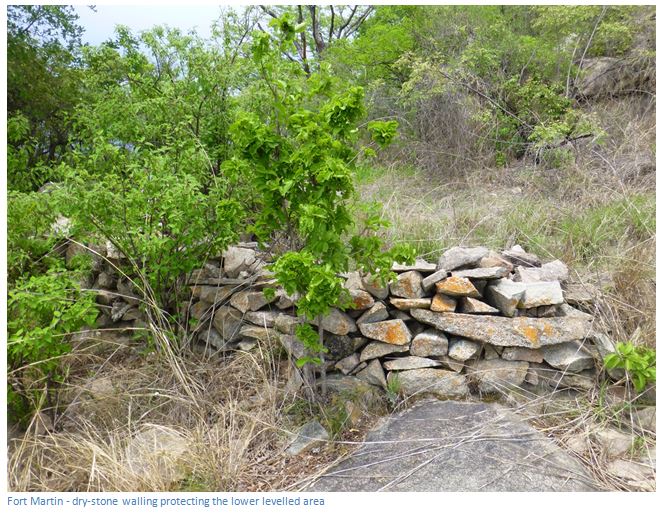

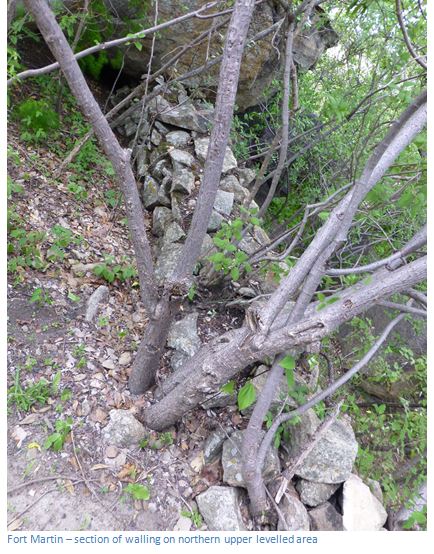

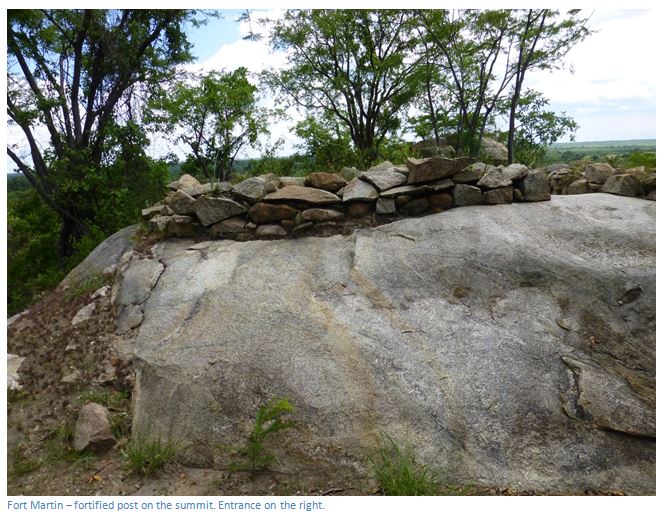

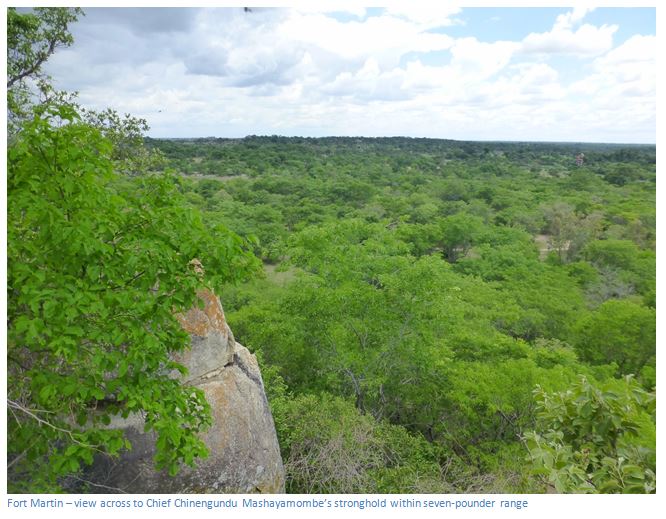

Chief Mashayamombe remained defiant in his kraal north of the Mupfure River and so a new Fort was established in a good defensive position and only a 1.5 kilometres away from his kraal; well within the range of the seven-pounder gun mounted here. It was named Fort Martin and occupied by the B.S.A.P. under Captain RC Nesbitt VC on 20 February 1897. The eastern side of the kopje facing Mashayamombe's kraal is unclimbable, while the lower, sheltered western sides have small level areas, which were protected with dry-stone walling and on which tents were pitched. "Fort Martin", Nesbitt wrote: "is very healthy, being splendidly situated, very high... it is impregnable and the best possible place. The only difficulty was the water supply which had to be obtained by running the gauntlet of any snipers who might be about.”

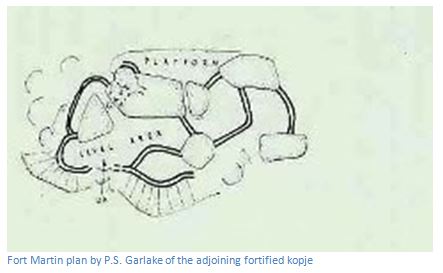

A smaller kopje a hundred yards away from the main fort was occupied by the African Police force and from here the BSAP were able to destroy the growing crops in the Mashona gardens. Chief Mashayamombe was forced to change his military strategy from defence. He tried to negotiate and buy off his besiegers by paying £15 10s. 6d. of hut tax and surrendering five old muzzle loaders. When this failed, he attacked in the early morning of 17 March 1897 with 300-400 of his warriors. They were driven off after three hours' of fierce fighting in which three native police were killed and two wounded.

One of Nesbitt's officers was Lieut. John Norton-Griffiths, who came up with Honey's Scouts, and who drew the sketch of the fort shown below. Norton-Griffiths was later knighted, and became well-known as "Empire Jack." Col. AS Hickman was given the original by Major RC Nesbitt VC who donated it to the National Archives.

Fort Martin came under sniper fire and in return Mashayamombe’s kraal 1.4 kilometres away was shelled by the seven-pounder for the next week, until on 24 July 1897, Fort Martin was the base from which the final assault on Chief Mashayamombe and the cluster of kraals including those of Muzhuzha, Muchena and Chifamba was launched with a total force of 670 men. The attack was planned by Lt.-Col. de Moleyns and Inspector Nesbitt, the garrison commander, to begin before dawn; Sir Richard Martin being at the fort and keeping in touch through a signal station. In the order of attack the African Police led by Inspector Colin Harding were followed by the dismounted European police under Inspector Nesbitt. The artillery and mounted unit under Capt. Roach and Sub-Inspector Ellet, moved to the right flank to cut off the Mashona if they retired and to prevent them from crossing to the south bank of the Mupfure River.

From the south bank the 7th Hussars under the leadership of Capts. Carew and Poore moved in from Beatrice and made an infantry assault on Mareverwa’s stronghold, east of Kaguvi Hill, which they occupied without loss.

Meanwhile the attack on Mashayamombe’s kraal continued; the first stockade was rushed, de Moleyns himself leading and supported by Chief Inspector AV Gosling, and H Wilson Fox, a volunteer who later became a director of the BSA Company. But the attackers came up against stiff opposition at Mashayamombe's main stronghold where Tpr. JC Lalor-Hull of the Rhodesia Horse was killed and Tpr. A Simmonds of the Police was mortally wounded. Troopers D Dennett and V Downes were severely wounded and three other Europeans slightly wounded, including Capt. J Brabant, who was with the African Police, which lost three men killed and two wounded and earned high praise for its bravery. Dr. Andrew Fleming, later Medical Director, had accompanied the column, and was kept very busy; one man was shot through the face, but the bullet was removed and the man recovered.

Chief Mashayamombe’s defenders retreated after a short, but sharp fight into a strongly fortified cave as soon as the kraal was rushed and kept up a heavy fire. The entrance to the cave was besieged through the day and night with small hand grenades of dynamite being thrown into the mouth of the cave; Tpr Jones particularly distinguishing himself.

The next day 25 July a Maxim was brought up to the cave entrance and soon after 215 women and children and six men came out and surrendered. At 9.30am a large charge of dynamite blew up the rocks surrounding the cave; 38 men then surrendered, and by the 26 July, 278 had surrendered.

After the battle it was learnt that Chief Mashayamombe had tried to escape on the night of the 24 July and was shot by one of the pickets; his body being identified by Capt. Brabant, although other sources say he was wounded by the dynamite blasts and appeared at the mouth of the cave before being shot dead. The Herald article says he killed himself, still other sources indicate he may have escaped with Kaguvi and Mukwati and sought refuge with Mbuya Nehanda, a powerful and influential female spirit medium in the Mazoe Valley.

The Herald newspaper in an article dated 21 May 2015 states that Chief Mashayamombe’s head was kept at a Bulawayo Museum until the 1960’s and then spirited away to Buckingham Palace.

There are many versions of Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s name, including Mashangombi and Matshayangombi.

This was the last major action of the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga. Kaguvi was one of the main spirit mediums after whom the First Chimurenga of 1896-7 was named and lived in the Mhondoro Communal Lands. With the death of his patron, Chief Mashayamombe, Kaguvi, whose real name was Gumboreshumba, “the foot of the lion,” claimed to be the personal spirit medium for the Mudzimu, or ancestral spirits involved in the founding of the Rozwi Empire of the seventeenth century, went on the run and on the 27 October 1897 surrendered.

Rhodes wanted the Imperial troops withdrawn to cut the BSA Company’s costs and for the newly formed British South Africa Police (BSAP) to take over as the Matabele Rebellion was at an end. The formation of the BSAP on the 1st October 1896, and the Chartered Company’s undertaking to finish the Mashona campaign with its own forces, meant only the 7th Hussars, remained in Matabeleland and by the end of November 1896, most of the Imperial troops had left Mashonaland with Alderson and Carrington leaving on Christmas Eve.

The new BSAP organisation had Col. Sir Richard Martin as Commandant-General, having been appointed by the British Government, following the disastrous Jameson Raid, which depleted the country of all its police forces. The BSAP Mashonaland Commander was Lt.-Col. the Hon. F. R. W. Eveleigh de Moleyns; his second-in-command was Chief Inspector H. Hopper and their first 180 recruits arrived in Salisbury in early December 1896.

The military strategy changed also to an offensive effort based on the establishment of small forts in areas where there was still resistance, such as Fort Harding at Goromonzi to contain Chief Chikwakwa, and Fort Martin near Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal.

Fort Martin remained a Police and Administration post for a further year and was disbanded in 1898.

The fort is still intact, with its low dry-stone fortifications at the base and summit of a kopje amongst a group of precipitous rocks.

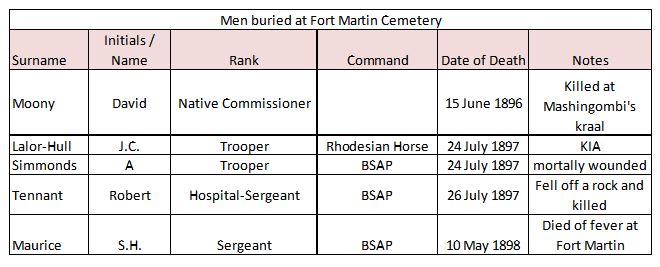

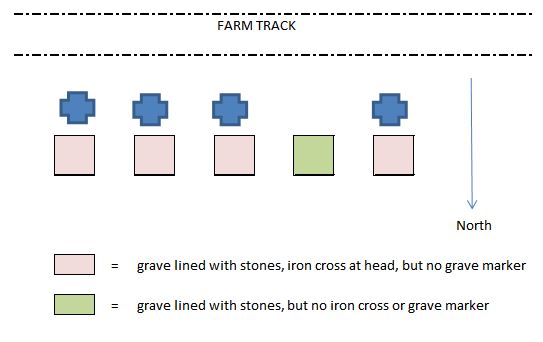

The Fort Martin cemetery is about 250 metres away to the south west of Fort Martin and has five graves outlined with stones as shown below. They are in order of date of death.

The BSAP compiled lists of the names of those buried at each site around the country before 1908 which were then sent by the Guild of Loyal Women (GLW) to the Gregory iron foundry in Cape Town. Here the names and dates were made into the familiar circular cast iron markers. Those who died prior to the death of Queen Victoria on 22nd January 1901 are headed “FOR QUEEN & EMPIRE” and those after are “FOR KING & EMPIRE.”

Four crosses remain, but the circular cast iron markers recording their names and date of death have been removed, so we cannot know who is buried where.

Strangely the graves are aligned north – south, and not east – west which is usual in Christian burials.

I can find no details of where Troopers John Selby Coryndon and Philip Jacobus Botha killed on 11 / 12 October 1896 have been buried. I feel sure their bodies must have been taken to Salisbury, or they would have been buried with David Mooney at the Fort Martin cemetery less than three kilometres away. Private Charles Grapes, who was mortally wounded and died on 20 October, died in hospital at Salisbury.

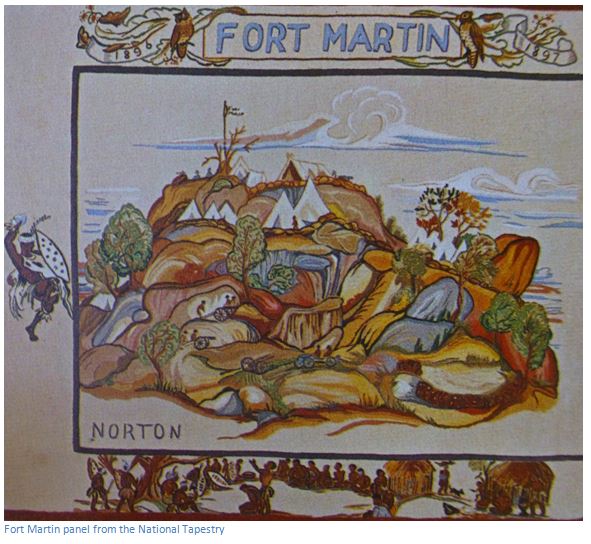

The panel featuring Fort Martin of the National Tapestry now at the Natural History Museum in Bulawayo was designed from the sketch made by Lieut. J Norton Griffiths, who served at Fort Martin. It was embroided by the Norton branch of the Women’s Institutes in Rhodesia; one of the forty-two panels similarly embroided in silk on linen and presented to Parliament in 1963. The upper border has an owl and Martial eagle, the central pattern features Fort Martin, whilst the lower panel features a Council of Chief and Headman at a Mashonaland village.

.

References

Col. A. S. Hickman. Norton District in the Mashonaland Rebellion. Rhodesiana Publication No. 3, 1958.

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890-1897. Rhodesiana Publication No. 12, September 1965

D.N. Beach. Kaguvi and Fort Mhondoro. Rhodesiana Publication No. 27, December 1972

BSAP website

BSA Company. Report on the Native Disturbances 1896-97

E.A.H. Alderson. With the Mounted Infantry and the Mashonaland Field Force. Methuen, 1898

Rhodesian Tapestry. Books of Rhodesia, 1971

W.H. Brown. On the South African Frontier. Sampson, Low, Marston, 1899.

Thanks to Brent Barber, Charles Castelin and Tim Rolfe for accompanying me.