Hope Fountain Mission

Hope Fountain Mission is the second oldest in the country after Inyathi Mission (formerly Inyati)

The impetus for the missionary movement in this country was provided by Rev. Robert Moffat who established a very personal and trusting relationship with Mzilikazi.

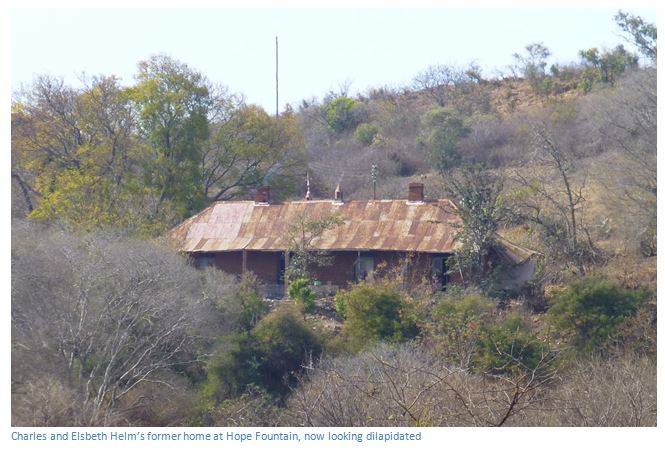

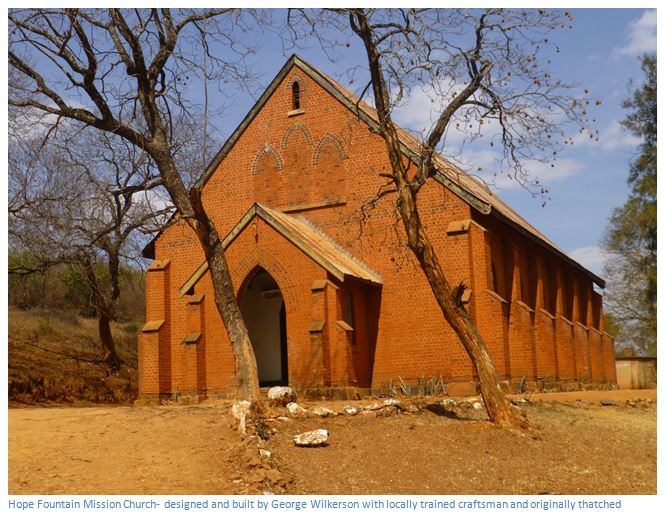

Although extremely important historically, Hope Fountain Mission has become somewhat rundown and in no way does it compare in its architecture ,or interiors, with the Churches at Serima, Cyrene, Chishawasha, or even Driefontein. However there are a series of photographs with descriptive notes of the roles played by the missionaries and teachers who contributed so much to the early education and training of crafts such as building and carpentry of this country. Many are fading and should be renewed before they become indecipherable.

In 1896 Frank Sykes described Hope Fountain as “the prettiest spot in the neighbourhood of Bulawayo…with a perpetual stream of clear water running between the hills, wooded slopes and grassy slopes, no more pleasant site for a residence could well be imagined.”

For all those that love Rhodesian Ridgebacks it is said that they were bred by the Rev Charles Helm who brought their maternal parents with him to Hope Fountain.

From Bulawayo take the Esigodini Road before taking a right turn onto the Hope Fountain Road. Distances are from the turnoff. At 4.3 KM pass the Bulawayo Drive turnoff on the right, 6.1 KM the narrow tar road ends at the entrance to the Girls School. Turn right and follow the untarred road down the hill for 700 metres and see the Church on the left.

An alternative route is down Burnside Road, which becomes Douglasdale Road and leads directly to Hope Fountain Mission.

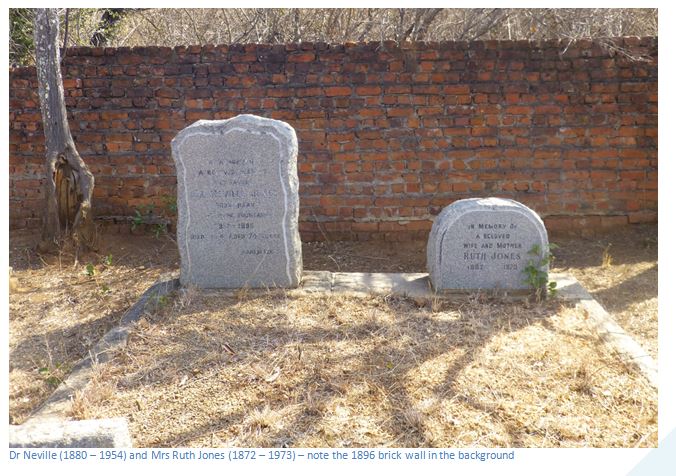

The cemetery is south west of the Church. Follow the road past the Church, turn right and take the first turn left, about 500 metres.

GPS reference for the Church: 20⁰15′52.68″S 28⁰39′14.89″E

GPS reference for the Cemetery: 20⁰16′03.19″S 28⁰39′06.00″E

Background and establishment of the first Mission station at Inyati (now Inyathi)

The Rev. Robert Moffatt arrived in South Africa in 1817 and was joined by his wife to be, Emily Unwin, two years later. They established the mission station at Kuruman, in the Northern Cape and their daughter Mary married David Livingstone in 1841. Robert Moffat had established a close and personal relationship with Mzilikazi whom he visited in 1829 at Hlahlandlela near Rustenburg near modern Pretoria and then at the Groot Marico River, near Zeerust in 1835 at eGabeni (Kapain)

The remarkable friendship between Robert Moffat and Mzilikazi was resumed when Moffat visited the King at Inyati in 1854, 1857 and 1859. At the 1857 visit Mzilikazi finally consented to a mission station being established in amaNdebele country and on 26 December 1859 six wagons outspanned at Inyati. William Sykes and Thomas Morgan Thomas had left from Cape Town in July 1858 trekking north to the London Missionary Society (LMS) mission station at Kuruman, where they were joined on their journey by John Moffat, the son of Rev. Robert Moffat. At Kuruman an epidemic struck and the 4 month old baby of Emily Moffat died, as did Mrs. Sykes and her new-born child. They were joined by two families, Rev Holloway Helmore with his wife and four children and Richard Price and wife and child, who were headed for the proposed Makalolo mission near the Zambezi, and they made the arduous journey together; remembered for the sand, mud, bush and tsetse flies, up to Matabeleland with two years supplies.

The Makalolo mission met with tragedy; the place given to them by Chief Sekeletu was swampy and malaria-ridden; all except Price and two Helmore children died of fever; the survivors were robbed of almost all their possessions and eventually struggled back to the mission station at Kuruman.

Lung sickness broke out as the three families reached the outskirts of Mzilikazi’s territory and they sent a message to the King asking for clean cattle to complete their journey. A regiment of AmaNdebele warriors inspanned themselves in place of the oxen and dragged the ox- wagons to Mzilikazi’s kraal at Emalangeni.

The establishment of the LMS mission station at Inyati "the place of the buffaloes" on 26 December 1859 will be left for another article. John Moffat and missionary colleagues were useful translators for Mzilikazi and then Lobengula, but they achieved few Christian converts. After Mzilikazi's favourite wife Loziba died in 1861, Mzilikazi left Inyathi and moved to a new kraal that he called Mhlahlandlela after his previous stronghold.

The Rev W.A. Elliott in his book Gold from the Quartz published in 1910 says: “In 1865 it became necessary for Mr. and Mrs. [John] Moffat to go south for medical treatment, and Mr. and Mrs. Sykes made a short trip to recruit in their company, for mission life in Matabeleland in those early days played havoc with health. This exodus left Mr. and Mrs. Thomas alone. Their position was difficult, and the work which claimed their attention various and abundant. Cattle had to be herded, and sheep and goats, nor could they be herded together; the gardens to be tended, the house-work done, to say nothing of the insistent claims of direct mission work. For all this the only help available was that of two little girls and a boy of nine years of age.

This is given as an ordinary illustration of the great strain under- manning of the mission imposed on the missionaries. The conditions altogether were unspeakably depressing. The climate depressed, the loneliness depressed, the apathy of the people depressed, the non- success depressed, the incessant strain of working beyond strength depressed, and the result was disastrous to the work. To withstand and overcome in Matabeleland in those early years demanded a small colony of, say, half-a-dozen families, whereas at times there was only one family, and occasionally one man. The thing was impossible.

Thus quite early in the history of the mission, it became evident that the work must either be abandoned or strongly reinforced. Two stations, with two families at each station, seemed ideal till better times should dawn. But the King set his face like flint against any suggestion of more missionaries. He was always friendly, and he faithfully stood by his promise to Moffat, but he would have no more missionaries. Attempt after attempt to get his assent was made through many years, only to meet with repeated rebuffs.”

Mzilikazi died on 5th September 1868 and after his death the izinduna, or Chiefs, offered the crown to Lobengula, one of Mzilikazi's sons. Several regiments disputed Lobengula's ascent, saying the rightful heir was Nkulumane and arguing that Lobengula was born of a Swazi woman, and therefore could not ascend to the throne. The succession question was ultimately decided by Lobengula and his impis crushing the rebellious Zwangendaba regiment. Lobengula's courage in the battle led to his unanimous selection and the coronation ceremony took place at Mhlahlandlela, one of the principal military kraals, from the 22 January 1870, with the actual succession taking place on 17 March 1870.

Establishment of Hope Fountain Mission by John Boden Thomson

John Boden Thomson (1841-1878) and his wife Elizabeth née Edwards were both from Scotland and left Newcastle-upon-Tyne on 9 August 1869; arriving at Inyati Mission Matabeleland on 29 April 1870 where John Moffat, William Sykes and Thomas Morgan Thomas were already based.

Thomson met with Lobengula at his new kraal at KoBulawayo, which means, “we have been killed” on the 23rd April hoping to negotiate a location for a second mission station near the King’s new kraal. Lobengula gave Thomson permission to seek a new location. Thomson was assisted by Hartley and Baines and they found an ideal location besides a natural spring, and called it Hope Fountain Mission. The Land was granted to the LMS on the 16th November 1870, with the King retaining right of possession if the Society ever left.

Again W.A. Elliott provides detail of the torturous negotiations: After some preliminary conversations, Messrs. Sykes and Thomson went to Bulawayo, the new chief town and royal residence, and boldly asked the King for a place where Mr. Thomson could build and teach. To the great pleasure and surprise of the missionaries, the King said, “Where do you want to build? The country is before you, go and seek a place." They could hardly believe their ears; it seemed too good to be true. That for which they had prayed and striven so long given at last. With hearts filled with gratitude to God they hastened to the search.

One of the indunas recommended a place as suitable for a mission station, and on examination they were mightily pleased with it. It seemed “just the thing." It was three miles and a half from Bulawayo, in a charming valley, with a beautiful spring of water, amid a large population.

Advice was sought from Messrs. Hartley and Baines, travellers of renown, than who none were more competent to form an opinion. They carefully examined the whole locality and gave a most favourable verdict. The two missionaries went at once to the King with their report, and were dumbfounded when Lobengula brusquely asked: “Why have you been riding about my country?”

"You told us to look for a new station where Thomson could build; we have been doing so with the help of Baines and Hartley." "I do not want any more missionaries; I have enough." With this shot the King went away, leaving the dismayed missionaries to their disappointment. ..Monday saw the King at the wagon, and the missionary introduced the topic uppermost in his mind. John Lee, an old resident, acted as interpreter, in place of Mr. Sykes, who had returned to Inyati. A long talk ensued, in the course of which many questions were raised.

“Were missionaries of any use to the people?” King and indunas seemed to be of opinion that the country was better without them. “What is the message from God? How would the message benefit him and his people? What is the Missionary Society?” To these questions from the King replies were given as seemed best under the very difficult circumstances. “I believe in God, I believe that he made all things just as he wants them to remain. I believe God made the Matabele just as he wished them to be; it is wrong for anyone to seek to alter them."

Then he said he was tired, but he added to his indunas, “I see that this message will do us good in this world and in the other. It is a great matter; I will take some time to think about it." At last Mr. Thomson told him that his supplies were done, and that he must go home. Then he frankly said, “I give your Society that valley for a mission station as long as they like, under me as King, and no trader is to build there."

Thomson had the first house built at Hope Fountain Mission and a vegetable garden which was irrigated from a dam on the river; there were not enough spades at the time, but friends helped out. Soon after, two locust swarms swept the gardens of every trace of greenery, but they were replanted.

W.A. Elliott writes: “The King had long promised to pay Hope Fountain a visit, and in July 1871, he came on horseback, and later on in his wagon. He had a good look round, took a great fancy to some of Mrs. Thomson's fowls, which she gave him; and was smitten by the satisfactory character of the bricks which were being made. He immediately set his own people to work to make bricks for himself.

Lobengula found this visit so much to his mind that in about a month's time he came again, this time in state. He was accompanied by his sister Mncengence, three wagons and about 150 attendants. It was a great occasion. He drew up to the house, and outspanned at the front door; and his beer pots and other paraphernalia nearly choked up the little mission house. The royalties took their food with the missionaries; and Mncengence with the King's children and attendants slept in the house. His majesty retired to his wagon for the night…Next morning the King examined the new house with surprised admiration. He must have one like it at Bulawayo. He liked the garden well, but the three little pigs called forth his loudest praises. Nothing would do but he must have some of the young when they should be born. Early next day the people came in increased numbers to greet their King, and for three solid hours they sang and danced before him. Altogether it was a most notable honour that the King had done the missionaries, but its frequent repetition was likely to rouse qualms.”

Inyati and now Hope Fountain were now established with their Christian work in full swing; the second missionaries to be appointed were the Helm’s to Hope Fountain (1875) and Mr. Elliott to Inyati (1877)

Thomson was then recalled, sometime in 1876 before the Helms arrived, to England for the establishment of a new mission at Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika and the party, including Thomson, Roger Price, Elbert Clarke, Edward Hore, Arthur Dodgshun and Walter Hutley left Zanzibar on 21 July 1877. The expedition was a total failure; travelling by ox-wagon across Central Africa proved a disaster. Price returned to England to consult with the Directors of the London Missionary Society, but never returned, and Clarke withdrew from the Mission in January 1878. The remaining group arrived in Ujiji on 23 August 1878, but Thomson died of a fever on 22 September 1878 and Dodgshun died on 3 April 1879.

Thomson replaced by Charles and Elsbeth Helm

The Thomson’s were on their own at Hope Fountain until 1875 when they were joined by Charles Daniel Helm (1844 – 1915) and his wife Elizabeth (Elsbeth) nee Baroness Von Puttkamer (1875-1913) on the 2nd December 1875. Charles and Elsbeth had met in London where Charles was training to be a missionary and Elsbeth was a governess. Their eldest daughter Jessie Constance was born in 1874 at Zuurbraak, near Swellendam, Cape Province and here his parents, both missionaries, taught Elsbeth to make bread and cure hams, soap and candle making. The Helms arrived after an extremely difficult journey with Elsbeth giving birth in Shoshong, in present day, Botswana to a son, Balfour on 18 August 1875, and then suffering from attacks of malaria and rheumatic fever at Tati.

They reached Hope Fountain on the 10th December 1875 and took over the Thomson’s first home of pole and dhaka; unbleached calico was used for the ceilings under the thatched roof, and a soil and ant-heap mixture for the floors. Each week more ant-heap mixed with cow dung was smeared on the floors.

However, Elsbeth’s health gave continued concern and William Sykes recommended the Helm’s return to Kuruman until recovered. They left Hope Fountain in May and after recuperating returned by the year-end, although their second daughter, Norah, born on 24 December 1876 did not survive her first month.

The isolated missionary families often visited each other. In 1877, the Helms with Jessie and Balfour visited Thomas Morgan Thomas and his large family at Shiloh when Caroline, Thomas’s second wife, a daughter of the Elliot’s, gave birth to their eighth child, Annie. They came again in May with William Sykes to nurse six members of the Thomas family who had succumbed to fever. All pulled through except Eben, aged 9, who died on 18th June 1877.

A few months later, the Rev. William Allan Elliott and his wife, Rose, arrived and stayed at Hope Fountain as Rose’s baby was due to be born very soon. Harold was born on the 5th October 1877 with both the Helms assisting. When the baby was a month old, William Sykes arrived from Inyati to escort the Elliott’s to their new home at Inyati. .

On the 28 May 1878, the Rev. Joseph Cockin and his wife, Annie, arrived to take up their appointment as the long awaited second family at the Mission. At the time Selous was staying with them recovering from fever whilst hunting up in Manicaland; he had reached Inyati on the old hunter’s road on 4 May in an exhausted state and after Sykes nursed him for three weeks came across to Hope Fountain. Selous writes of Elsbeth “She was one of the kindest and generous hearted of women. Thanks to the wholesome food and unremitting kindness and attention I received beneath their hospitable roof I soon recovered my health and in two months’ time was well enough to start on another hunting trip.”

In 1879 Charles Helm officiated at the marriage of Cornelius van Rooyen and Margareta Bloemhof. It was from van Rooyen’s hunting pack and Helm’s bitches that the Rhodesian Ridgeback breed originated.

The same year, Charles Helm organised the first postal service for the traders, hunters and missionaries in Matabeleland. “Runners” went fortnightly to Tati to hand over the mail to other runners and to bring back any mail for Bulawayo. There was an annual charge of between £1.10.0 and £2.10, or 5/- a letter and the service was a great benefit to all those residing in Matabeleland.

The Jesuit Fathers; Croonenberghs, Depelchin and Law began to visit the Helms quite frequently. On Boxing Day, 1879, Croonenberghs and Law spent the day with them, Croonenberghs painted and sketched their homes and gardens and enjoying Elsbeth’s cooking and fresh fruit and vegetables from her garden. The Fathers had finished replacing the sailcloth and painting of one of Lobengula’s wagons for Christmas day. Croonenberghs delighted Lobengula by painting an “L” with a crown above it on one side of the wagon and an “M” (for Mzilikazi) on the other side.

In 1881 the big event was the birth of Alexis, on 19th April. Their daughter Jessie, who was seven, remembered seeing to the dinner and burning herself in the process.

In 1882 the Helms had an LMS meeting in Kuruman. By now the family were proficient trekkers and everything and everyone had its place in the ox wagon. Each child had a bag hung inside the wagon for their toys and books and even the dogs came. Their routine was to trek from 5am to 7am. Then cattle would be put out to graze and the breakfast and mid-day meal prepared. Bread was made, clothes washed, and the beds and wagons tidied. At 4 pm they trekked until 6pm. After supper the children were put to bed and they would trek from 8pm until mid-night. Jan Grootboom, who features in the First Umvukela or Matabele uprising, and subsequent Indabas, was a driver and great favourite with the children; making them whips and telling them stories.

Twins Erica and Hedwig were born on 16th August 1882 but were premature; the Elliott’s had not arrived to help from Inyati and Hedwig only lived for three weeks.

Father Peter Prestage visited the Helms on 17th and 18th August to collect his post and described the Helm’s home approvingly: “The furnished room in a good model for a residence in a hot climate, height 12ft, width 16ft and breadth 18ft. There are 3 other rooms on the ground floor. There is a verandah and stoep in front.”

The arrival of David Carnegie on 13th October was a great joy, especially for Charles Helm to have a companion for his daily walk and swim.

Ralph Williams who visited the Helms about mid-December described Elsbeth as “a charming lady with many accomplishments, she could sing charmingly and had an overflow fund of happy good humour besides being still a pretty women. From her and her husband we received much kindness.” Selous also arrived on one of his frequent visits. It was his custom, after knocking at the door, to walk in and hang up his hat and coat on the rack next to the door and he would entertain the family in the evenings with his zither.

In January 1884 Elsbeth and the children went to Europe so the children could go to boarding school and see their relations. They reached De Aar, which was the railhead, and Charles returned alone to Matabeleland arriving in late July.

David Carnegie left in charge of Hope Fountain

Finally in December 1885 it was Charles’ turn to go to Europe and David Carnegie, who had married Margaret Sykes, daughter of the Sykes’ at Inyati, was left to manage affairs at Hope Fountain. Charles arrived in England in May and went to Germany for two months before returning with the rest of the family to England. They left the eldest children in England: Jessie and Winnie at a boarding school for missionary children in Sevenoaks in Kent, and Balfour in Blackheath, London.

The trek from Kimberley to Kuruman took a month and on arriving back at koBulawayo they visited Lobengula as was customary. They found him suffering from gout and lying on the floor of his hut covered with a blanket with an earthenware jar filled with charcoal and wood In the middle of the hut to keep him warm. A young buck, a kid and a cat lay next to the fire. Sykes and Rees squatted while Charles introduced the newcomers to the King. Lobengula gave them a good welcome and said to Elsbeth “Why did you throw your husband away for so long, but I am glad you have taken him on again.”

They arrived at Hope Fountain on the 10th March to find that the African who had been left in charge there had been murdered after a “smelling out” process by the witchdoctors. As Bowen Rees was anxious to see Inyati they left most of their goods unpacked, and set off for Inyati where Charles found the people upset about Sykes’s death, but very pleased to meet Rees. The Elliott’s house needed re-thatching and was in bad condition.

Back at Hope Fountain, they decided that their kitchen was habitable and they would therefore use it for their living quarters, and sleep in the wagon tent. They resigned themselves to this arrangement until June when the thatching grass would be ready for the roofing. Even the outhouses were beyond repair; so Charles had a hut built at the cost of 30/-, to serve as a dispensary. Luckily, only one case of their belongings, which Charles had carefully packed before leaving had got wet from a hole in the thatch, but nothing of great value was spoilt. The people at Hope Fountain were delighted to have them back again and brought them presents of meat, eggs and vegetables.

Elsbeth was to suffer for a few months from agonising tooth-ache and headaches and the children were not well, but Elsbeth thought that as soon as they had become accustomed to the climate once more, they would recover very quickly. She was pleased to be back in her home in spite of it being only one room. She made it look very homely and was pleased to entertain Count Von Schweinitz in it and was hoping to welcome the Bishop of Bloemfontein, Knight-Bruce, later in the year.

Charles had been drawn into the political and economic negotiations that were beginning. John Moffat had resigned from the LMS in 1879 and in the following years he held a number of Government appointments and was appointed British Representative to Bulawayo in 1887. On the 11th February 1888, he entered into a treaty with Lobengula, on behalf of the British Government. The Treaty secured Matabeleland and Mashonaland to British influence, ruling out influence from any other country.

Elsbeth started a sewing class once she had settled in again. The children at school wrote home regularly in German, in spite of their having forgotten quite a lot of the language. The two younger children, Alexis and Erica, were now the only children left at home. Erica’s daughter recalls her mother telling of the rivalry between her brother and herself as to who could get up first to see the cows being milked. She was at a disadvantage because she had to button on her boots so, in desperation, one night she decided to go to bed with her boots on. When Elsbeth came in to tuck them in for the night she saw the two little bumps in the bed and quietly removed them.

The Bishop of Bloemfontein, Knight-Bruce, arrived in May 1888, on his journey to Mashonaland, he was feeling ill when he arrived at Bulawayo but, as he was anxious to see Charles, he rode out to Hope Fountain. He wrote in his diary: “the sight of the Mission house after the little ride of 9 miles in contrast to the Chief’s Kraal gave me a feeling of the blessedness of Christianity such as I had never understood before.”

Charles and the Bishop discussed the customs of the African for a while and then Charles sent a boy to show Knight-Bruce “the road”. Charles, concerned that the Bishop was not well, visited him the next morning, which was the 26th May, and walked over with him to visit Lobengula, who questioned the Bishop on his motives for coming into the country. The Bishop’s health deteriorated, and that night he slept in the wagon, but the next day Elsbeth put him on the sofa in her kitchen, and, as he says, “Every possible kindness and attention were given me. Never shall I forget the Christian hospitality of the two people”.

The Cape Government in August that year made Charles’s position as Postmaster official. He was supplied with a 23mm diameter date stamp inscribed “Bechuanaland”, in addition to the name of the office. Charles knew that Lobengula would resent the implication that Matabeleland was part of Bechuanaland, as Lobengula’s relations with Khama were already strained over a border dispute, so he deleted the offending word and asked Sam Edwards at the Post Office in Tati to do the same.

The British Expedition, led by Sir Charles Warren, had occupied Bechuanaland at Khama’s request, in 1884, and it had become a Protectorate of the British Government. Sam Edwards had been sent up to Matabeleland the following year with Lieut. E.A. Maund to inform Lobengula of the establishment of the Protectorate and to assure the king of the continued friendship of the British Government.

The special connection between Charles and Elsbeth Helm and Hope Fountain Mission

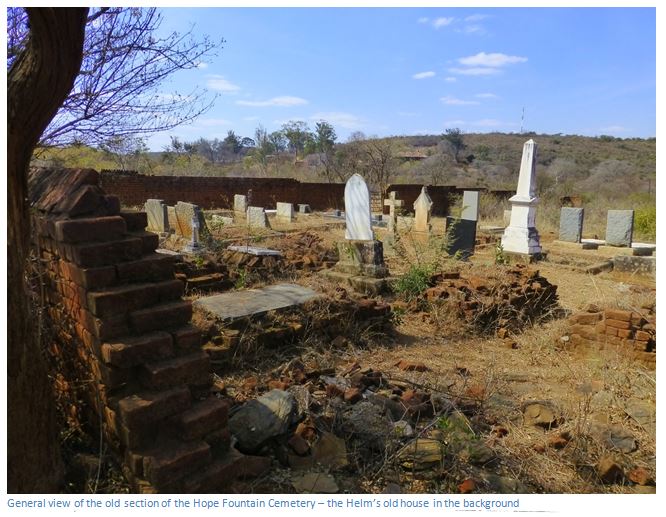

Charles and Elsbeth Helm stayed on at Hope Fountain for another 39 years and both are buried in the historic churchyard. The plaque on the wall of Hope Fountain Church says they kept open house in the early days of the country’s history and were greatly beloved by a large circle of friends.

The Helm’s daughter, Mrs Jessie Lovemore wrote the following account of Missionary life under Lobengula:

“Our day at Hope Fountain started with short morning prayers followed by breakfast at 7:30. My father then went to the kraal to see the cows and calves, goats and sheep and the few oxen we kept at Hope Fountain for ploughing, or for pulling the Scotch cart. Then he gave a look around to the mealies, or wheat according to the times of the year. About nine o’clock he returned to his study, a room slightly away from the house where natives were already collecting, and the next couple of hours were spent in attending to the hundred and one ailments from which they were suffering, a break being made for a cup of morning tea. Dinner was at half past twelve, after which the household retired for a rest, either to sleep or read or sew or a bit of each. At 3 p.m. all met for afternoon tea, and a little later my father and Mr. Carnegie went to the river for their daily swim, walk and general look round. Not being able to have tennis or other outdoor games for lack of facilities, the men had to have other exercise. I think that, and not going out into the hot sun from mid-day till 3 o’clock, had a great deal to do in keeping them fit. Being so far from medical aid, and with wife and children under their care, they were wise to be careful. After supper, soon after sundown, we had evening prayers, to which the servants came. It was held in the native language, and always included a hymn. For the rest of the evening my father read, wrote letters, studied and did little odd bits of work for which he found no time during the day. Bedtime was rarely before 10 or 11 o’clock.

My mother’s day started earlier, of course, attending to the children and, till we gradually trained native girls in household work, getting breakfast ready. After breakfast came the daily round of housework. Cooking, laundry and house cleaning took up all the morning, and the quiet time after dinner was always enjoyed.

The first two mission stations in Matabeleland, Inyati and Hope Fountain, were established in 1859 and 1871 respectively, by permission of Mzilikazi and Lobengula. As Matabeleland was so far from the coast and because of the fear of witchcraft, superstition and indifference of the natives as a whole, it was decided not to establish any other mission stations for a while. The natives came to services, and enjoyed the singing of hymns. The four missionaries, therefore, steadily carried on their work, hoping for results someday but as long as it was a native state under a native chief who had absolute power of life and death, it was not possible to break down the native’s fear. Most of the mission work consisted of doctoring the bodies of the natives. One could only pray that their souls would be touched in time. Witchcraft abounded, and no native would have risked owning a book, for had anyone died in his kraal, or the crops of any of them failed, it would have been put down to that book, and the owner would probably have lost his life. Hence the missionaries were very careful not to endanger in any way the lives of the one or two who showed signs of awakening.

Every morning at all the stations you would see a crowd of sick people waiting to be treated. It was remarkable that though they were so steeped in the belief of witchcraft, they never for a moment doubted the missionary and his cures. For instance my father was one day away in Bulawayo, ten miles from Hope Fountain, when a man came to my mother with something wrapped up in a leaf. He said a woman had bitten a piece off his nose, and would she sew it on! He had tried to have it sewn on with some hair from an ox’s tail, without success. He was very truculent when my mother firmly said she did not know anything about that sort of thing, but at least he consented to await the return of my father. The wound was doctored - but without the piece torn off, for “hot weather” reasons.

My father was a great smoker, and one morning a man came in suffering from toothache. The tooth had to come out, so my father laid his pipe down on a stone nearby and took up a suitable pair of forceps. He was tugging away when out of the corner of his eye he spotted the victim’s leg go towards the pipe, big toe and next one spread out ready to grab the pipe. A man came another day with an appallingly shattered arm. He had been out on one of their raids, and been shot six weeks previously. He’d returned with the impi, a six weeks’ march. There was no chloroform available, but Mr. Selous and my father managed to amputate the remains, and it all healed up well.

The London Missionary Society always tried to have two missionaries at each station. When Mrs. Cockin’s first baby arrived, my father and mother attended to her. As there had been in the earlier days, several cases of women dying in childbirth owing to ignorance on the part of the husbands about such matters, the London Missionary Society insisted on the missionaries working at the hospitals for six months before leaving England in order to gain a little general experience, especially in midwifery. Poor Mrs. Cockin was very bad, and it was decided to use instruments. Mr. Cockin administered the chloroform but was so distressed that he fainted almost immediately, so my mother had to take over and she was terrified she would give too much. However, everything went well and the baby throve, and a couple of years later Mrs. Cockin had another infant, under easier circumstances.

The missionary women took their lives in their hands when they went pioneering. The Cockin’s spell of work was very brief. When they went for a short visit to Shoshong (Khama’s Capital) in Bechuanaland he developed severe malaria and died. Mrs. Cockin went to Kuruman as teacher for some years, and retired later to England. For two years my parents were alone at Hope Fountain. In 1828 Mr. Carnegie was sent to join my father. He married in 1886 Mary Sykes, daughter of Rev. and Mrs. William Sykes of Inyati Mission. For 15 years the two missionaries laboured together in wonderful harmony and friendship, together with their families. This spirit has been handed down to their children and grandchildren. When the London Missionary Society decided to open a new station near Figtree, about 30 miles west of Bulawayo, the Carnegies were appointed there. Now that Rhodesia was being populated and roads made, farms occupied and the country generally civilised, there was no need to put two missionaries on one station, to combat the utter loneliness. The Carnegies were very sad to leave Hope Fountain.

It is said that Charles Helm brought two bitches from South Africa, both rough coated and grey-black in colour, and that the hunter Cornelius van Rooyen bred them with his hunting pack which comprised the breeds Khoikoi, Greyhound, Bulldog, Pointer, Irish Terrier, Airedale Terrier, Collie, Deerhound and possibly Bull Mastiff. At the time no one noticed that either of these two bitches possessed a ridge on its back, but time these two bitches became the foundation of what we call today, the Rhodesian ridgeback.

Lobengula thought highly of Helm who had studied amaNdebele language and culture and in October 1888 when Rhodes sent three agents, Charles Rudd, James Rochfort Maguire and Francis Thompson to Matabeleland, he was required to be present as interpreter and adviser throughout the deliberations which led up to the drafting and signing of the Rudd Concession.

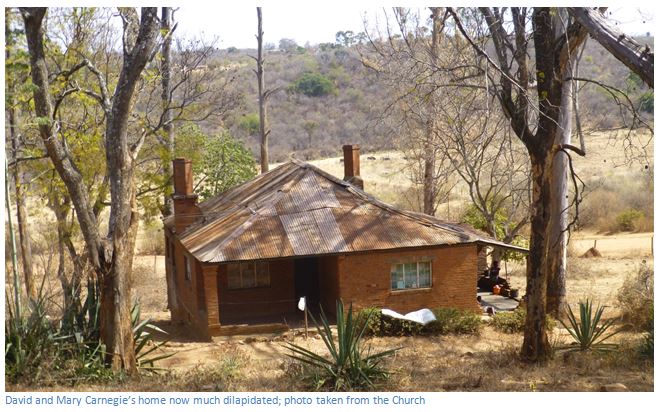

David and Mary Carnegie – long-term residents who served Hope Fountain Mission

Another wall plaque commemorates Joseph Cockin who arrived at Hope Fountain in May 1878 and died of fever at Shoshong on 3 February 1880. The wall plaque says: “he was a fine man physically, most devoted and earnest in his missionary enthusiasm, and descended from a good stock, his grandfather having been a founder of the London missionary Society.” J.D. Hepburn in his book Twenty years in Khama country and pioneering among the Batuana of Lake Ngami writes that Cockin was on his way south to Klerksdorp with his wife to fetch provisions and windows for the house they were building at hope Fountain when he died. His wife continued as a missionary at Kuruman from 1881 to 1886.

The ideal of two mission families at each of two mission stations became an accomplished fact when David Carnegie arrived on 13 October 1882 and three years later married Mary, daughter of William Sykes at Inyathi Mission. He founded the Centenary Mission in 1896 and was succeeded by George Wilkerson on his death in Bulawayo Hospital on 29 January 1910 aged 54 years and is buried at Hope Fountain.

His wife, Mary Carnegie (nee Sykes) was born at Inyati in 1862 and was the third European girl born in this country. The first born was Livingstone Moffat in April, 1860; David Thomas was born next in July. Three, girls were born at Inyati in 1862; Mary Meta Moffat in March, Annie Thomas in April, (but she only lived two months) and Mary Margaret Sykes, later Mrs. Carnegie, in December. On the day of her birth, Mary was presented with a cow and a calf by Mzilikazi, King of the Matabele.

In later life she could recall the coronation of Lobengula, Mzilikazi’s successor, in 1870, and the famous battle of Zwangendaba, fought in the same year between Lobengula and the Induna, Umbigo, who refused to recognize Lobengula as King. She also retained a vivid memory of the early pioneer hunters and explorers who made Inyati their headquarters; men such as Thomas Baines, Henry Hartley, Carl Mauch, F.C. Selous, “Elephant” Phillips and others.

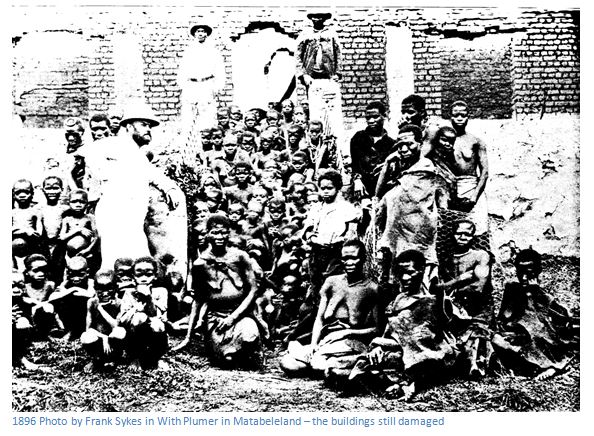

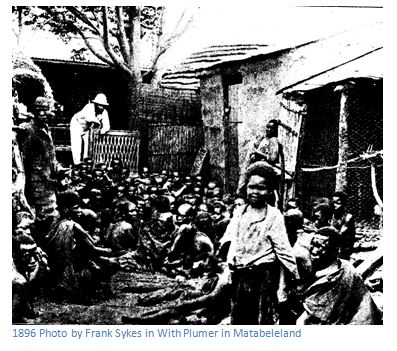

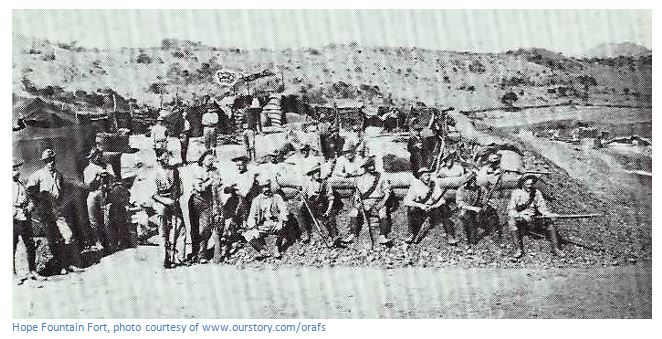

In 1896, Hope Fountain Mission was looted and burnt down during the First Umvukela or Matabele rebellion before the arrival of the Matabeleland Relief Force which camped nearby in May 1896 and built a fort. Terence Ranger says: “David Carnegie set off toward the end of 1896 to find his school children and their parents who had fled to the Matopos. He descended deep gorges, climbed stony kopjes, crept through narrow passes, “going up and down, round about, threading our way as if we had been in some ancient city made by man.” He found the Hope Fountain people “in a lovely ravine” where women were “digging their gardens” and “a beautiful stream of clear water ran beside the garden.”

The photo below shows Rev Carnegie in front of the ruined Mission house with some of the women and mission school children after peace had been concluded.

David Carnegie wrote Among the Matabele, a book published by the Religious Tract Society in 1894 and also translated with his wife Pilgrim’s Progress into isiNdebele.

Technical Training at Hope Fountain

George Wilkerson arrived in 1896 and started the Hope Fountain Industrial Institute where he trained local amaNdebele men as builders. They built the existing Churches at Hope Fountain, Inyati and many others around the mission station. The wall plaque says in 1909 he married Constance Evelyn Clustin and the next year took charge of Centenary Mission station near Figtree which had been established in 1898. David Carnegie died very unexpectedly in 1910 aged only 54 years. Jessie Lovemore says Centenary closed down in 1912 as it was in a proclaimed European farming area. The same year George Wilkerson joined the Baptist Missionary Society and carried out missionary work in the Congo, dying in 1941.

Neville Jones extends the teaching facilities at Hope Fountain Mission

Neville Jones was the assistant Home secretary of the LMS in London when he married Ruth Collard. In 1912 they moved to Hope Fountain where he was in charge until his retirement from missionary work in 1935. He was the driving force behind the Girls Boarding School and the Teacher Training School.

In 1913 he discovered an archaeological surface site in the grounds of Hope Fountain and missionary work often took him to the Matopo Hills, where he spent his spare time searching for caves and excavating archaeological deposits at Bambata Cave in 1917, excavated in 1918 with G. Arnold, and in 1929 with A.L. Armstrong, and at Nswatugi Cave in 1922, excavated in 1932. He also did much exploratory work in the drainage area of the Gwaai River with A.L. Armstrong and made the first attempt to correlate prehistoric tool industries with climatic phases at the Victoria Falls. In 1926 he published his first archaeological book, The Stone Age in Rhodesia.

From 1936 to 1948 he was Keeper of the Department of Prehistory at the Natural History Museum in Bulawayo. It led to the publication of many archaeological papers and books, including The Prehistory of Southern Rhodesia and My friend Kumalo under his pen name of Mhlagazanhlansi. He died in October 1954 after being awarded an OBE in 1948 and Doctorate of Science in 1953 and he and his wife are buried at Hope Fountain cemetery.

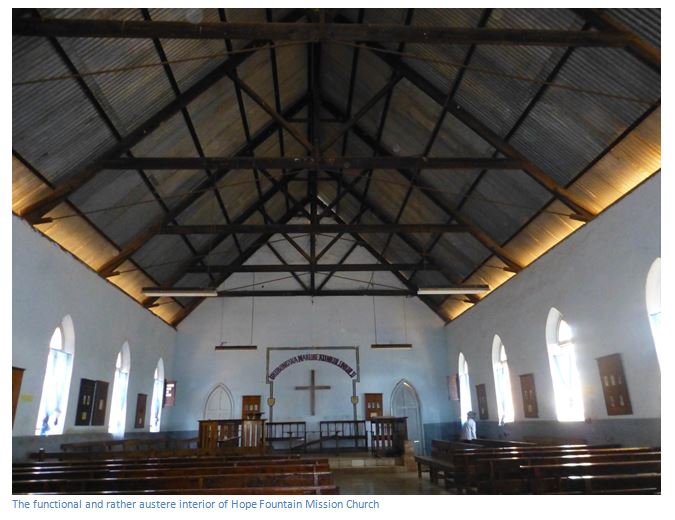

The very simple interior of Hope Fountain Church is somewhat severe, almost barn-like with the high corrugated iron roof held together with metal tie-rods. The walls are hung with photographs and notes of the devoted missionaries and teachers that served their country and communities so well. Jessie Lovemore says the Church was initially beautifully thatched, but despite having a lightning conductor, it was struck by lightning and burned down and had to be replaced by the corrugated iron roof.

The Girls School was founded in 1915 and the Teacher Training School in 1927 and also today there is a Christian-based organisation working with orphaned and abandoned children in Zimbabwe called Hope Fountain International.

Other Missionaries who gave devoted and loyal service over many years included W.G.Mc.D and Nan Partridge, Sitjenkwa Hlabangana, Mtompe Khumalo who belonged to the Royal Family and was born at the King’s kraal at eNyathini. Zhisho Moyo who started as a herd boy, Mrs Moyo who rose from teacher to Tutor Assistant at the Hospital before taking charge of the Clinic and Maternity Centre over 21 years, before becoming Boarding mistress for another 21 years. Henry Boli Mashengele started as a mule herder and after worked at Hope Fountain for 57 years as a teacher and carpentry instructor became a Boarding master and Church Elder.

Major Henry Stabb’s impressions of Hope Fountain

In 1875 Stabb was the first European to walk from Gubulawayo to the Victoria Falls with an inDuna Gleite as guide and carriers supplied by Lobengula. [See the article Major Stabb’s hunting trip in 1875 to the Zambesi Valley via Gubulawayo under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Stabb visited Matabeleland from July 1875 and describes Hope Fountain Mission as about 3 miles from Gubulawayo. Revd. Jon Boden Thomson was resident missionary with his wife and family.

On 21 July Stabb with James Fairbairn, William Francis and George Westbeech rode over for lunch with Thomson and his family. He describes Mrs Elsbeth Thomson as “a pretty and most agreeable little woman, full of hospitality and love for her three little boys, whom she and her husband seemed in great danger of spoiling.” Their house he describes as large and roomy and substantially built of brick and charmingly situated just under the brow of the hill with a stream winding down the valley in front of it. Pretty gardens led down from the house to the stream where there were: “orange trees, bananas, apple and peach tree, rosebushes, the castor-oil plant and many specimens of English flowers. The valley below Thomson is capitally irrigated by damming the stream in different places and here are waving fields of English corn, maize and oats and vegetable and potato gardens which quite gladden the eye and bring us back once again to visions of civilization, whilst grazing away up the valley his bullocks, cows and goats add to the pastoral effect.. Altogether it is by far the prettiest, most complete and best-kept mission I have seen and it is Thomson’s opinion that nearly all temperate and semitropical productions would grow well here.”

Thomson had brought John Halyat from Sechele’s to complete the Thomson residence and he was brick-making and getting the roof water-tight and also building a kitchen and schoolroom near his house. Halyat’s next job was to build a wall around the little cemetery which is described below. William Thomson who had recently died at Hope Fountain on 25 January 1875 at the age of seventeen months was buried here. Local traders and hunters had subscribed to the cost of the wall, but the project was progressing slowly with even the bricks having to be made.

Stabb describes Elsbeth Thomson as equally as industrious – everything the family wore was made by her with all the household work and kitchen under her supervision. After a “capital dinner with plenty of potatoes and good vegetables” they all walked to the top of the hill with its view of the surrounding countryside and range of hills. They were standing more or less on the watershed with rivers flowing north to the Zambesi and south to the Limpopo. He describes a “curious hole in the ground” which Thomson tells him the Mashona dig a red clay (isibuda) with which they paint their bodies.

After their walk Elsbeth Thomson: “gave us some delicious coffee with lots of fresh good milk and excellent new bread and butter, a treat that none but those who have been for a length of time without can properly appreciate.”

At this time Revd Thomas had arrived back in Matabeleland after being barred from the Inyathi Mission for trading with the Matabele, but William Sykes was travelling up to replace him and so was Charles Helm who Stabb had met at Shoshong: “so the spiritual welfare of the Matabele does not appear to be likely to be overlooked.”

Thomson: “who appears a really sensible fellow, says he has not yet made a convert, but he is not at all discouraged, his work will live after him. If he is not successful in evangelization, he believes himself to be in civilisation, and the former will follow the latter. He has established schools and has many attendants, some of them being the King’s children, so doubtless he is doing a good work quietly and patiently.”

Hope Fountain cemetery

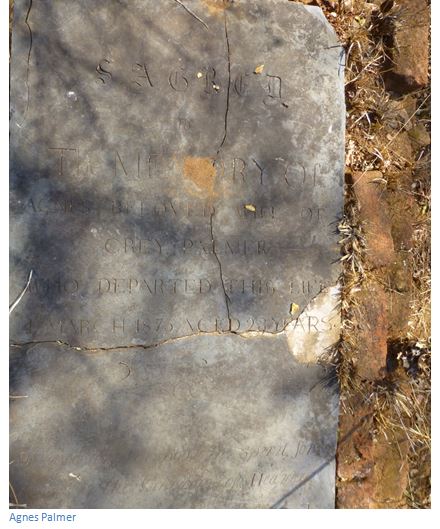

Agnes Palmer was very young when she married Grey Palmer, a trader in Matabeleland, in Cape Town and they set off for the far interior by ox-wagon. They reached Gubuluwayo, and for some offence Palmer fell into a fury and thrashed one of the young wagon men who died from his injuries. This shocked Mrs Palmer who was already frail and didn’t recover; despite being nursed by Mrs Thomson "with great tenderness" she died on 4 March 1875. Grey Palmer died soon after. Jeannie Boggie in her book First Steps in Civilizing Rhodesia says the Rev Neville Jones told Mrs Palmer’s sister this story when she visited her grave.

The inscription on her grave shown below reads; “Sacred to the memory of Agnes, the beloved wife of Grey Palmer, who departed this life 4 March 1875, aged 23 years."

Hope Fountain Fort

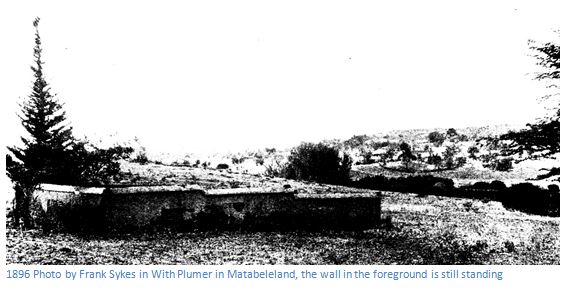

On 23 May 1896 Capt. C.W. Halsted was accompanied by 47 men of the Matabeleland Relief Force to Hope Fountain Mission which they found burnt and deserted and were fiercely attacked, but over the space of three hours managed to beat off their attackers. They constructed Hope Fountain fort on the eastern end of hill which overlooks Hope Fountain Mission.

The fort has an unusual shape, very different from the usual standard patterns of fort employed elsewhere. As can be seen from the photo, it had earth walls which were topped off with a double layer of sandbags which took them to shoulder height and does not appear to have had a firing step, or a ditch.

Acknowledgements

Jeannie Boggie. First Steps in Civilizing Rhodesia, 1940

http://www.rhodesians-worldwide.com/rwmagazines1/vol212/files/assets/pages/page0016.swf

Rev. W.A. Elliott. Gold from the Quartz. London Missionary Society, 1910.

http://www.rhodesianridgeback.org.za/rrif/Origins.html

N. Jones. Rhodesian Genesis. Rhodesian pioneers’ and Early Settlers’ Society. 1953

Mrs Jessie Lovemore. Missionary life under Lobengula from the website www.rhodesians-worldwide.com

I.J. Cross. Rebellion Forts in Matabeleland. Rhodesiana No 27, December 1972. Pages 1-28