The Siege of Deary’s Store at Abercorn June 21st – July 13th, 1896

This almost unknown site today was the scene of a desperate fight that took place in June / July 1896. Similar scenes had occurred in Matabeleland in late March 1896 when the Matabele uprising or first Umvukela broke out. At Edkins’ Store, Cumming’s Store, Ingwenya Store, at Inyati where Native Commissioner Graham and his courageous comrades were surprised and overwhelmed and at Thabas zika Mambo where the West Brothers were murdered.

In Mashonaland, at the Alice Mine at Mazoe and Hartley Hill, small parties of besieged Europeans managed to hold out until relief came. At Deary’s Store, Abercorn (now Shamva) here described, the seven survivors held out for 23 days, although John Rowland died of dysentery on the return journey to Salisbury.

There are many tales of massacres and sometimes hairbreadth escapes by small parties of Europeans; but this feat at the Abercorn Store for simple courage and endurance in view of their isolated position exceeds all others, although at the time the incident appears to have been treated as of no great consequence.

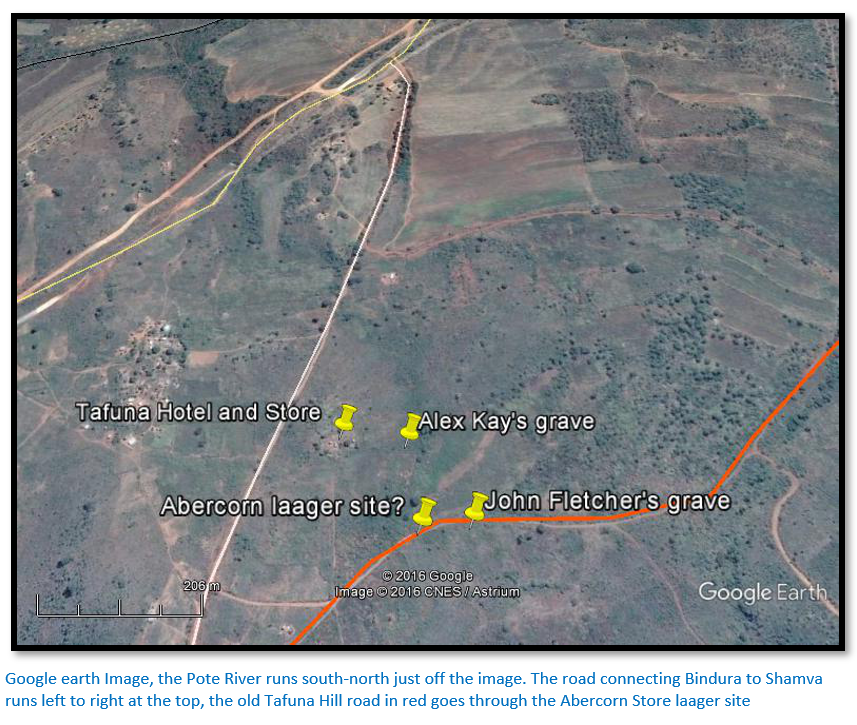

Take the (A2) Enterprise Road, passing through Newlands and Chisipite and continuing until the tollgates. Distances are from the tollgates. 0.2 KM turn left on the (A13) Shamva Road; 15.4 KM pass Ewanrigg turnoff on the right, 21.6 KM reach Bally Vaughn entrance on the left. 44.0 KM reach Murmurgwe rock art site on the left, 68.8 KM reach the Bindura road and turn left. There are 4 KM of very broken up road until 72.4 KM cross the railway line. Drive onto the excellent double-tar road (the old Tafuna hill road joins from the left) and continue past at 74.6 Km the entrance to the GMB depot / signpost to the Ming Chang Sino Africa Mining and Milling Company. At 75 KM turn left onto a track just short of where the tarred road ends.

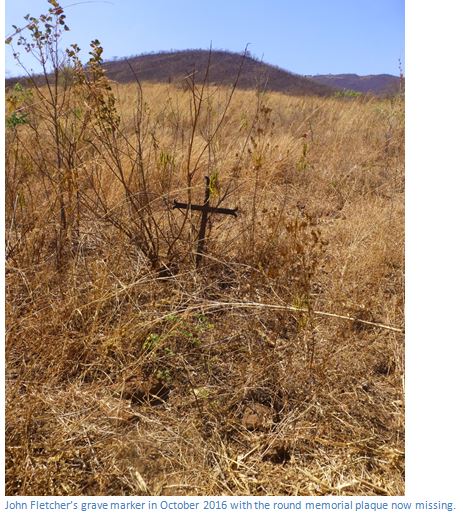

Continue down this dusty track, which is very slippery and muddy in the rainy season, and continue past the first road that joins from your left after 450 metres. After 1 KM turn left onto the second road going east and after 170 metres joins the old Tafuna hill road. Continue on another 200 metres and park. The iron grave marker for John Fletcher’s gravesite is visible about 20 metres from the road south looking to Tafuna hill.

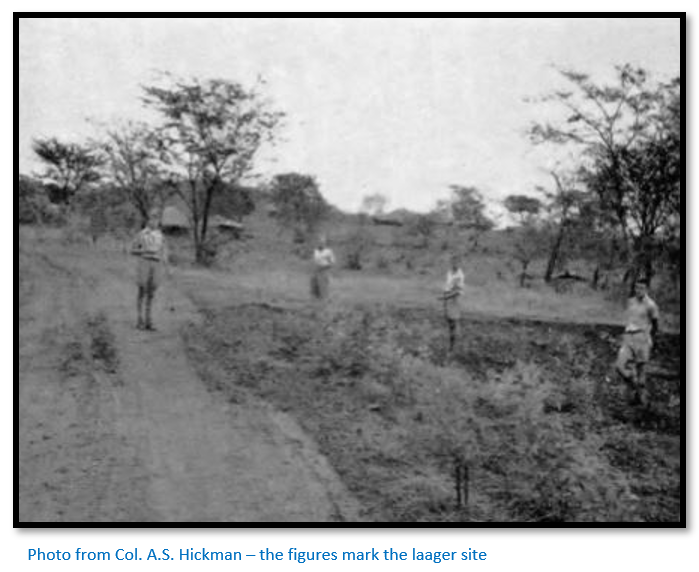

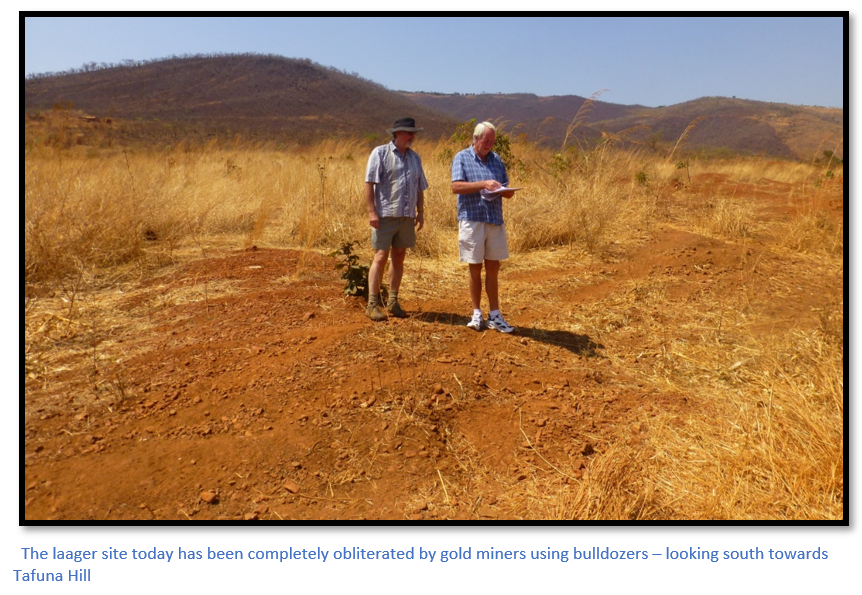

The siege site is 70 metres west of the grave marker, but all local signs of the siege have been lost as the area was bulldozed by gold seekers and in the rainy season is dug up for growing maize.

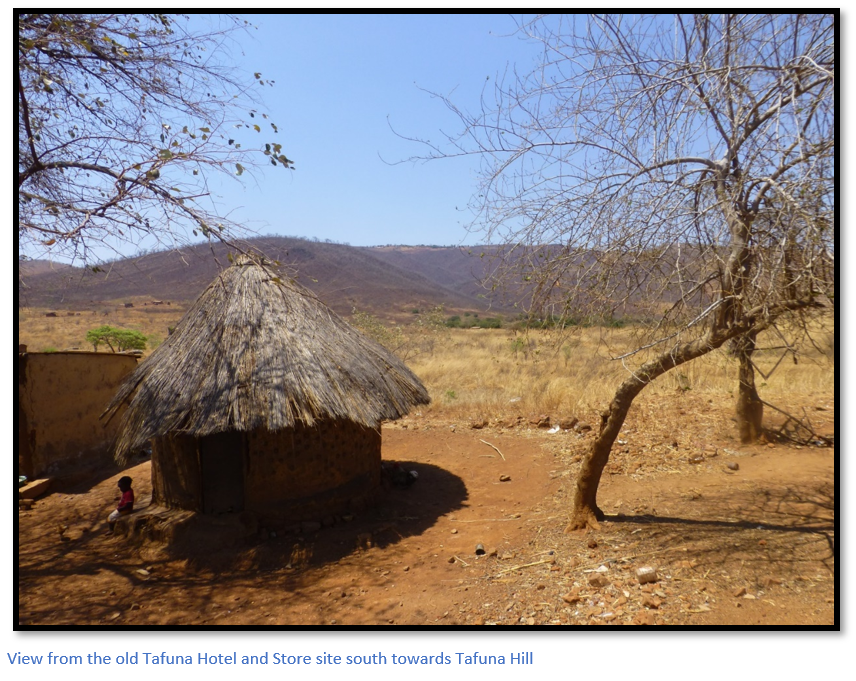

The old Tafuna Hotel and Store is just 180 metres to the north west of the siege site and several footpaths lead to the cluster of huts on the prominent rise. The cement floor and broken bricks are visible.

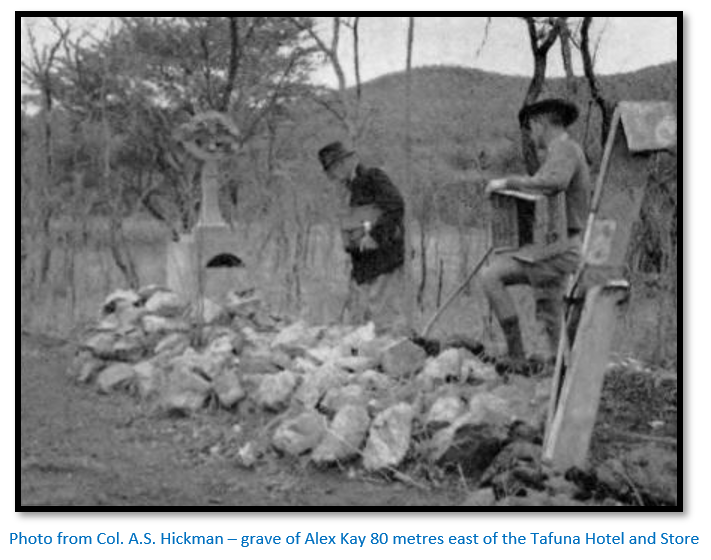

The site of Alex Kay’s grave is well hidden in the grass and still covered in blue quartz stones, but the grave marker seen by Col. A.S. Hickman in his photograph has gone.

GPS reference for John Fletcher’s grave: 17⁰20′15.49″S 31⁰30′41.41″E

GPS reference for the Deary's Store siege site: 17⁰20′15.44″S 31⁰30′39.16″E

GPS reference for the Tafuna Hotel and Store: 17⁰20′10.79″S 31⁰30′35.21″E

GPS reference for Alex Kay’s grave: 17⁰20′11.49″S 31⁰30′38.44″E

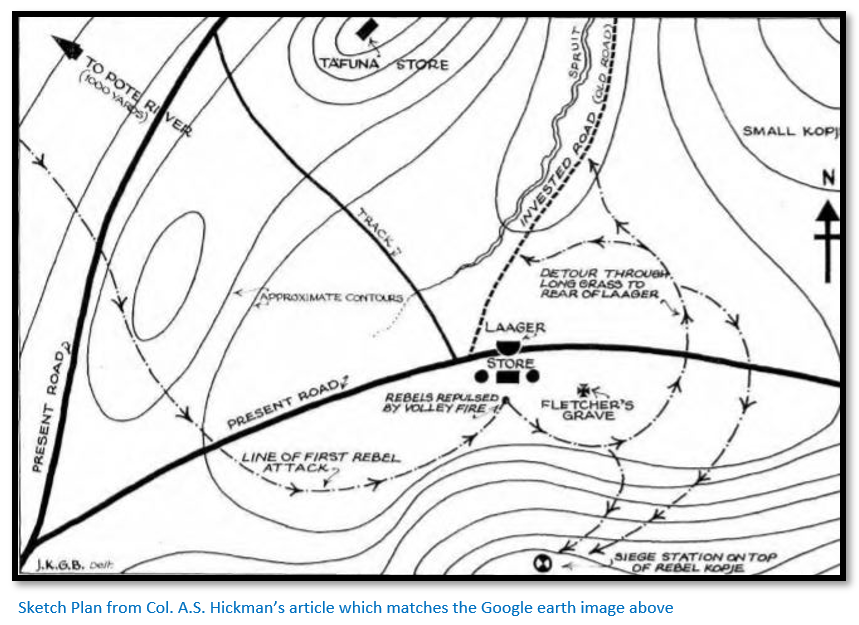

This story would have remained as newspaper articles if Col. A.S. Hickman had not written The Siege of the Abercorn Store in Rhodesiana No. 9 of December 1963 which is highly recommended reading.

In 1896, there was a small community of prospectors, miners and traders at Tafuna Hill, some six kilometres southwest of modern day Shamva town, but then called the Abercorn district, after James Hamilton, 2nd Duke of Abercorn and Chairman of the BSA Company.

Deary and Co. had established a trading store at the site of the subsequent siege north of Tafuna Hill and on the track of the old road to Salisbury, now Harare. When the Matabele uprising, or First Umvukela had broken out in late March 1896; nobody suspected similar trouble in Mashonaland. However, it was noticed there was a general increase in lawlessness, especially in the Mazoe district, now Mazowe, where the police had withdrawn from their camp and this and other mining camps had been broken into. The Acting Administrator, Mr Justice Joseph Vintcent issued a Notice to Prospectors and Others through the Government Gazette of 15 April 1896 which said: “..although his Honour the Acting Administrator and the Council have no reason to believe that there is any probability of a similar rising of natives in Mashonaland, yet they consider it desirable to point out that, should the natives of Mashonaland take advantage of the present crisis and attack isolated stores, mining camps and farms, it is important to impress upon such persons as are in outlying and isolated positions the necessity of vigilance.” On 24 April the Mazowe residents petitioned for ammunition: “most of us have rifles but are short of ammunition…a precautionary measure…we feel perfectly safe” and one thousand rounds were issued to them.

When the news of the murders at Hartley on 15 June and Beatrice on the following day reached Mazowe by telegraph, the residents decided to withdraw to Salisbury, but it was already too late, and they were forced into their laager at the Alice Mine.

Even before the siege of Deary’s Store began, a party of four prospectors who had taken the track through Mazoe and continued down the Mazoe Valley, were fired upon whilst passing Chipadzi’s kraal; Joseph Francis Deane and James Stroyan were wounded, with John Fletcher and George Holman unhurt, and they brought news of the uprising to the scattered mining community when they reached Deary’s Store at Abercorn on the evening of Saturday 20 June. Deary’s Store had not been designed for defence; it was in a bad position on the level; with rising ground on every side, particularly the lower slopes of Tafuna Hill, but there was no other choice. Only 180 metres to the north was the future site of the old Tafuna Hotel and Store, which would have made a much better defensive site, but there was neither the time, nor resources to locate their laager at this site.

Edward Charles Broadbent says the local people had been very friendly and the uprising caught them by surprise. However, he stated that for some time before these events there had been a big demand for powder and caps for muskets, but that just before the Hartley murders, trade had suddenly stopped.

The settlers quickly prepared for their defence and fortified Deary’s Store from Sunday 21 June and remained in a state of siege for 23 days until relieved by a patrol from Salisbury.[i] Broadbent, their leader, is described as a prospector working between the Mazoe and Pote rivers and seems to have taken charge of the besieged group and later wrote an article for the Rhodesia Herald after their rescue.

At that time, Deary’s store buildings consisted of two store huts with a kitchen and mess huts in line on either side, and the group decided to set up the laager about 15 yards to the north. It was in the form of a half-circle with the flat side to the north, furthest from the store. The men burned down the store hut to the south east as the long grass came up close and provided cover for any attackers. “The foundations of the laager were made from sacks of mealies; cases of corned beef, liquor, and pickles were used for the breastwork. We loopholed it as well as we could, and filled up surplus holes with limbo, bundles of socks, clothing, etc.,” said Broadbent.

The inside measurements of the laager were about fourteen square metres (150 square feet) and the initial occupants consisted of nineteen persons comprising nine European men, five Zambezi men, one woman, a girl, and three young boys, together with six dogs that later proved most useful in their warnings of the rebels approach. Twenty-five other Zambezi employees deserted when the first shots were fired.

Louis Hermann had a horse and volunteered to ride to Salisbury to report on their situation. He left early the next day, Sunday 21 June, but was overpowered and murdered at Makombe’s kraal. Three of the Zambezi men were also sent with notes to Salisbury, but they may have deserted as they were never heard of again.

Work on a laager began early that morning Sunday 21 June, but before it had been completed, Mashona fighters came in force from the Pote River side on the west and opened fire at 9:30am. They were driven off by volley fire and moved through the long grass south of the store and also blocked the road to the north. Edward Broadbent was injured with a dislocated shoulder in this first exchange of shots, and several Mashona were shot dead, including their leader. The remainder swore vengeance before retiring into a kopje overlooking the store to the southeast where a noisy council-of-war was held, during which time the defenders hurriedly completed their makeshift laager.

The Mashona shouted that they wanted to parley, but no notice was taken of them, except by John Fletcher, who against orders and advice, walked to the edge of the long grass, held up his arms to show he was without firearms, and was immediately shot dead. His body lay where it fell and is buried at the same spot where his grave may be seen to this day about 70 metres east of the laager site on the farm “The Carse.”

From then onwards there would be no respite for the besieged. On the 24 / 25 June, very determined attacks were made with Broadbent estimating between 70 – 80 attackers armed with guns and battle-axes and assegais. Late on 25 June, the majority of the rebels left, leaving sufficient men to maintain the siege and keep up a harassing fire on the laager. When the rebels crept up close through the long grass to the south and southwest, the defenders threw out plugs of dynamite with short fuses.

The defenders had plenty of tinned foods and made bread using beer; but had only whisky, gin, beer and sweet red dessert wine to drink. The most serious problem was the lack of water as they were about 900 metres from the Pote River to the west. The first trip to get water was successful, but in the second, none of the four Zambezi men ever came back to the laager. However, one of them, January, decided that it was impossible to return to the laager alive and made his way back to Salisbury and reported on 10 July 1896 that the survivors at Deary’s Store were in mortal danger.

For the third trip, the remaining Zambezi man, a boy and the girl went out. The man returned with bad assegai wounds and subsequently died, the boy returned the next day and the girl was not seen again. On the fourth trip, the unwounded Europeans, Pickering, Ragusin and Rowland and a young boy successfully managed to bring water from the Pote River, but their footprints were discovered and the besiegers: “built a cordon of scherms (bush fences) around us, and pretty effectively cut off any chance of egress on our part.”

Their attackers shouted out that they knew there was no water in the laager, and that they would soon force them all out of it. They added that if they handed over the goods and guns, they would let them go; but when the small party took no notice of the offer, they added they would kill them all as they had killed their own leader.

Broadbent says their sanitary arrangements were “pretty well as defective as they possibly could be” as nobody could leave the laager; Holman and Rowland suffered from dysentery throughout the siege. This combined with the stench of dead bodies “made things horribly unpleasant” and they all suffered from fever and the lack of water.

As Col. Hickman says in his article it is amazing that they managed to keep up their morale in such awful circumstances. They were fortunate in having medical dressings and managed to keep their wounds healthy, also there was plenty of tinned food and ammunition from Deary’s Store.

The occupants of the laager were now in a desperate situation with Fletcher dead and Broadbent, Deane, Stroyan and Holman wounded; only Pickering and Ragusin were not wounded; although they were all suffering from fever, and Rowland had acute dysentery. All the Zambezi men and the young girl had disappeared or were killed; the young boys and the woman had tried to escape but were prevented from doing so as Broadbent feared that if the attackers learned of their perilous state, they would rush the laager and overwhelm them. Four of the six dogs had been killed and one wounded.

Their attackers kept up a desultory fire throughout the siege and shouted over constantly that the amaNdebele had captured Salisbury and killed all the occupants and they would not be rescued. Broadbent said by the morning of the 13 July; “things were looking very gloomy indeed, it was our twenty-third day in laager; our water, wine and stout about finished, and just about enough beer left to bake one loaf. At about 10:30am we were all lying down in a semi-somnolent, exhausted condition, when we suddenly heard a clatter which we at first took for a rattle of shields, and thought the Matabele were on us. We sprang to our guns and beheld the never-to-be forgotten sight of the relief column cantering around the corner. Our delight can be better imagined than described. We set up a hysterical cheer which was answered by loud hurrahs by the advancing men.”

The rescue of the besieged men

Jono Water’s article In Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 39 on their rescue was from an account in The Rhodesian Times and Financial Times which was launched on 31 July 1896 – just a few weeks after the relief patrol had set out for Abercorn, now Shamva, on 11 July.

Marshall Hole comments that the military men at Salisbury had shown little inclination to mount a relief effort of the men at Deary’s Store. It was only after Duncan came in from Charter on 10 July and heard the account from January of their plight that a rescue effort was launched.

The Abercorn Patrol

The patrol comprised forty mounted men of the Natal Troop and twenty-five men from the Salisbury Field Force under Captains Taylor and St. Hill, Lieutenants Snodgrass and Maclaren,[ii] Nesbitt and Campbell. After some opposition a Maxim gun on a travelling carriage and ambulance wagon were added to the patrol. They left at 8pm[iii] on Saturday 11 July.

The patrol travelled by a route close to the present Shamva Road, the next day Sunday 12 July they had a brief skirmish and travelled on. The journey of nearly 100 kilometres took just over 38 hours and as Broadbent’s account above relates, they arrived at Deary’s Store, to the great relief of the besieged in just in the nick of time on Monday 13 July at 10:30am.

The patrol together with the survivors wisely returned to Salisbury taking the route along the Mazoe river. The different route was probably chosen to avoid being ambushed, (accounts say a trap had indeed been laid along their outward route) but also to assess the military situation of as much of the countryside as they could. Kraals at Chipadzi’s were burnt down and at Cass’s farm at Mazoe the patrol was fired upon as they moved up the road alongside the Tatagura river. An outspan was made at the Gwebi river to give the men and horses some rest where a large contingent of Mashona assembled in the distance at about 1,200 yards before being driven away by Maxim gun fire. One of the siege survivors, John Rowland, died on the journey back on 14 July as a result of dysentery and pneumonia.

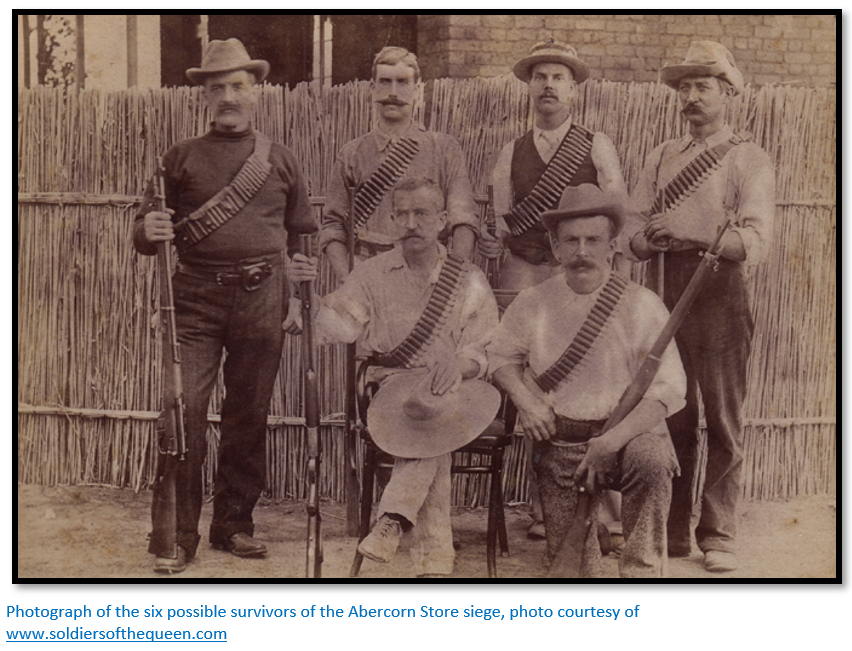

It has been suggested by the author of the website of www.soldiersofthequeen.com that the photograph below may be of the six survivors of the Abercorn siege, although this has not been verified. The man seated has a double-barrelled rifle; the others have Lee-Metford, or Enfield, or Martini-Henry rifles.

A table of those in the laager includes:

Name | Comments | Service record |

Broadbent, Edward Charles | wounded | Tpr Salisbury Field Force 1896 |

Deane, Joseph Francis | wounded | Tpr Salisbury Field Force 1896. |

Fletcher, John | killed in the siege on 21st June and buried on site |

|

Hermann, Louis | murdered at Makombi's kraal whilst riding to Salisbury (now Harare) for help |

|

Holman, George | wounded | Tpr Salisbury Field Force 1896. Guide Rhodesia Horse |

Pickering, J. |

| Tpr Salisbury Field Force 1896 |

Ragusin, A. |

| Tpr Salisbury Field Force 1896 |

Rowland, John Robert | died from dysentery and pneumonia on the 14 July, the day after Duncan's relief force arrived | Served in the Warren Expedition of 1885. Joined the B.B.P. Pioneer Column No.6 Attested 18/4/1889 appointed to “A” troop 27th May. Transferred to Transport Troop 4th June appointed as conductor with rank Sgt Served as Tpr with the Victoria Rangers in the 1893 War. The roll shows him with the 1896 bar. |

Stroyan, James | wounded | Tpr Salisbury Field Force 1896, Tpr Umtali Volunteers 1897. |

Zambezi natives (5) | one was wounded and died, the remainder were killed, or ran away |

|

Shona woman |

|

|

Shona boys (3) |

|

|

Shona girl | killed, or ran away |

|

Presentation of an Illuminated Scroll to Mr A.H.F. Duncan after the rescue

The following is quoted from Jono Waters’ article. He doesn’t state which newspaper the quote is from, but I assume it was The Rhodesian Times and Financial News.

“An interesting ceremony took place on Saturday afternoon last, when a deputation of gentlemen, including representatives of the Abercorn survivors, met and presented Mr. A.H.F. Duncan, the surveyor general with an Illuminated Address, in recognition of the distinguished part he took in effecting the rescue of the besieged men in the district. The Reverend Mr. White made the presentation and said undoubtedly there had been many brave deeds performed during the war, but Mr Duncan's stood out conspicuous amongst them. The expedition had been organised solely by him and he had practically saved the lives of seven men.[iv] (Applause) Mr Muirhead emphasised Mr Duncan's action as a combination of courage and duty and contrasted it with the trivial behaviour of certain other officers in the laager. He detailed Mr Duncan's ride from Charter and the organisation of the patrol, and pointed out that when volunteers were called for, three times the sixty wanted came forward, which showed that the neglect of rescue duty lay upon the officers and not the men. (Applause)

Mr Nicholson referred to the spontaneity of the subscriptions for the Address. Not one had been asked for a contribution; all had given voluntarily. (Applause) Mr Schaumann said, in addition to this brave deed, Mr. Duncan deserved their gratitude for the way he had stuck to them and the country. (Applause) Mr Broadbent, on behalf of himself and his rescued comrades, thanked Mr. Duncan deeply for what he had done. There was a consensus of opinion that if it had not been for him, they would never have been relieved. They could not have held out more than another two or three days at most. They needed no memorial to remember him. They would never forget him. (Applause)

Mr. Duncan, in reply, thank the deputation for the Address, which he felt was no ordinary one, but dictated from the heart. One thing that gratified him was, that when he called for volunteers, three times the number required came forward because they considered it their duty to relieve men being done slowly to death outside. (Applause) He was glad to have been the instrument of saving life. In regard to the Address, he would cherish it as long as he lived, especially as coming from the people amongst him his lot was cast, and with whom his work might be in the future. (Applause) The Address, which was from the design and drawing of Mr Alfred Lyons was a very handsome one and contained artistic marginal representations of scenes in the rebellion by the same artist. In the centre was a capital portrait of Mr. Duncan, and at the foot a photograph of the seven rescued men. The lettering of the Address was the work of Mr Biller. Mr. Duncan left Salisbury for England on Sunday by private convoy.”

Present-day remains of the siege at Tafuna Hill

In his article in Rhodesiana No. 9, which I have quoted extensively, Col. Hickman says they found John Fletcher’s grave, which was dug near where he fell; seventy metres from the laager site, beside the road to the old Ilex Mine before it climbs up Tafuna Hill.

At the time of Col. Hickman’s visit the round memorial plaque read: “---Fletcher, BSAP, --96, For Queen and Empire” and in addition had a square piece of tin with the following painted: “Murdered in the Rebellion. 23.03.96. RIP” Clearly the details were wrong; John Fletcher was not a member of the BSAP when he was killed, and the date of his death was 21 June 1896.

Behind the grave marker can be seen the hill that overlooked the laager site where their Mashona attackers held their council-of-war and kept up a harassing fire, in the background Tafuna Hill.

The laager site itself, is against and on the south side of the modern gravel road. Although there is nothing left of Deary and Co.’s store which was built of pole and dhaka; Col. Hickman found plenty of broken bottles of Holbrook’s sauce, Eno’s fruit salts and pickles, all favourite foods in 1896, extending for 3-4 metres parallel to the road and marking the laager spot and he picked up many old rusty nails in the dust of the road that presumably came from the packing cases that were used for the breastwork on the laager.

North of Fletcher’s gravesite and the laager site is a small kopje where the old Tafuna Hotel and Store was located and 80 metres east and at the foot of the kopje is a cemetery with one named grave; that of Alex Kay who died on 20th March 1894, two years previously. Kay’s grave is covered in quartz rocks and covers the large area of 4.5 x 2.7 metres and had, when visited by Col Hickman, an elaborate cross of galvanised zinc at its head…now gone. There are other graves here, probably victims of fever, but all records have been lost and I can find no information on Alex Kay. In between this cemetery and the Tafuna Hotel, Col. Hickman found a litter of bricks and broken bottles, including a bottle of “Kirker’s Special Liqueur Scotch Whisky,”

Amazingly, the same broken bottle with lettering on the neck reading “Kirker’s Special Liqueur Scotch Whisky” was purchased at a local Harare auction by Tim Rolfe. Kirker’s is no longer produced, but Mitchell Bros Ltd of Glasgow, have found the record of a company meeting held in 1893 by the directors of Messrs. Kirker Greer & Co Ltd. Inside the bottle is a note written by Col. A.S. Hickman saying: neck of Whisky bottle found on the site of the Abercorn (Shamva) laager of 1896. Found in 1958.”

The Tafuna Hotel was on the summit of the small kopje and its foundation features in the photographs. The Store was at the foot of this kopje and consisted of two buildings that were moved down from the Ilex Mine on Tafuna Hill about 1915 and converted into one building that became the hotel, before becoming the store. In 1916, William Samuel Whaley came to Tafuna Hill with his wife and two small children prior to building a house at the Trio Mine and says: “there was a hotel of sorts at Tafuna Siding, one and a half miles from the mine, but it was run by a man whose ideas of cleanliness were so primitive that Josie after one month refused to stay there any longer.”

Col. Hickman adds that the Tafuna Hotel was owned by Galante, then by Mannheim and Weiss, and from 1927 to 1941 Mr and Mrs Marketos ran the store at the base of the kopje. They were aware of the grave but had not heard of the siege of Deary’s Store.

A further account ‘Reminiscences’ by J.T.-J who was the senior NCO on the Abercorn patrol, appeared in the Rhodesia Herald on 19 March 1926

Again, this is quoted from Jono Waters’ article in Heritage of Zimbabwe No 39 of 2020.

The remarks made by A.R. Morkel on the relief of Abercorn in the 1896 rebellion in a recent article in your columns seems to show that there was some misapprehension as to the condition in which the men there were found and it may be well now to recall the facts regarding this patrol, which left Salisbury at the end of June or early July 1896[v] upon what was thought by many - some of whom were in high authority - to be a forlorn hope. The first Hartley patrol - of which the writer proposes to write in a future article had returned, driven back from Mashingombi’s kraal[vi] by superior numbers and with some casualties. The Mazoe Patrol[vii] had also returned and most of the settlers and miners at Lo Magondi’s[viii] had found their way into the laager by the first week of July and it was realised there was little hope of any survivors being left in the country district, except at Hartley and Abercorn.

A somewhat acrimonious atmosphere prevailed in the laager as to the probabilities of their being still alive, as to the possibilities of a rescue. At this junction - and it is useless to conceal the fact that depression was very deep in Salisbury - the arrival of Mr AHF Duncan, the Surveyor-General, from Bulawayo,[ix] when he had come accompanied only by Evered, his servant, on horseback, had a wonderful effect on the spirits of the beleaguered garrison and I think I am right in saying that it was his influence which decided the powers that were, to attempt the Abercorn patrol. Even then there was a good deal of delay[x] and argument as to whether a Maxim could be spared or not, but eventually the patrol was formed consisting of experienced men with a Maxim and a light hospital wagon and mules. Mr. Duncan accompanied the patrol[xi] which was under the command of Captain George St Hill, with Lieutenants Snodgrass and Maclaren and Alec Nesbitt and A.D. Campbell as guides - the former for his knowledge of Mazoe and the latter for his knowledge of the road.[xii]

Hearty send off

The writer cannot verify the date at the moment, but it must have been about 7 or 8 of July[xiii] that the patrol, sixty-five strong, left Salisbury laager about 8 o'clock in the evening[xiv] and was given a hearty send off by all the inhabitants of the laager. It was very difficult to get away as so many goodbyes were left to the last moment. However, we got away at last and the last three men who left, St Hill, Snodgrass and myself were presented with bottles of whisky by Mrs Marshall Hole and Mrs Vincent, not without tears. There was a good moon, and it was bitterly cold. I rode the whole night with A.D. Campbell, who was the guide through this part of the country, and nothing occurred until the next morning at about 7 o'clock, just when we had off saddled about thirty miles out. A number of Mashonas, evidently not realising that that we would such a large body, came running at us out of the bush from a spruit on the road, but were speedily scattered by Maclaren's Maxim and we did not see another native except gesticulating on distant hills during the whole march to Abercorn Store, which we reached without any trouble the following morning about 8 or 9 o'clock.

The Survivors

When we judged we were within about a mile or two of the store, then owned by HJ Deary, we fired a shot or two in order to give some kind of notice of our coming, and Snodgrass and myself rode on slowly, well flanked on either side and in a few minutes came in sight of the laager and we could see the attitudes of the men, resting on the sides with their rifles at the ‘present.’ On seeing us they shouted, and in fewer minutes than it takes to write Snoddy and myself were shaking hands with the survivors. Not a native had been seen that day. The laager merits description. It was only a few feet from the huts of which the store consisted, and evidently, they had no time or opportunity to choose a better spot but had hastily got into the open as far as possible and there constructed their defences from the bags of grain, soap and cases of store goods to a height of about five feet. It was oval-shaped and about ten to twelve feet long and not more than half as wide. They were about a thousand yards from their water supply and although one trip had been made to the water in the earlier days of their siege, I believe I am right in saying that being 22 days without fresh water.

Lime Juice and Gin

At this time, I cannot recollect more than a few of the names of the rescued men: Pickering, in charge of the store: Jack Rowland an old prospector an ex CM[xv] and old George Holman, a Cornish prospector. They were, if I remember rightly, nine persons rescued – all of whom were wounded more or less severely. There were also in the laager two native women, whom they detained, as they dare not let them go to tell their relations the plight of the garrison. And their sole drink, from compulsion was lime juice and gin. There were cases of whisky and other spirits, but they found that this mixture was the one which caused least thirst. Fortunately, it was winter and bitterly cold. Had it been summer they could not have survived.

They were in a terrible condition, but not as Mr Morkel suggests, from intoxication. Poor old Jack Rowland died the next day from wounds and exhaustion - he must have been over sixty years of age as he had served in the old Frontier Armed Mounted Police,[xvi] which has converted into the CM Rifles. We buried him and also Fletcher, who had gone out in the early days of the laager to hold parley with the natives but had been shot about 30 or 40 yards from the laager and there we found his blackened corpse. Imagine the feeling of those in that frail laager at having to view the corpse every day – not daring to bury it and not able to raise a head above the loopholes for 22 days or more.

A roaring business

It was a very happy day for us all, in fact it had begun to get rather too happy as the storekeeper had resumed business as if they had been only a slight interruption. And he was doing a roaring bar business too. However, Mr. Duncan saw that something would have to be done, so he gave me orders (I was the senior NCO) to set apart one bottle of whisky per every man for the return journey, to close the store and then destroy all the stock after taking what we wanted as supplies. An inventory was taken, the store was cleared, the bar closed, amidst much grumbling which the promise of one bottle per man somewhat allayed. Fortunately, there were lots of tinned luxuries in the store and so everyone fed well even if they also did partake of the liquid's and they were on the whole a very good-humoured lot. I should say, even at this distance of time, that the feeling uppermost in all our minds was one of elation at having pulled off the rescue and the more so as most people in Salisbury thought it was a forlorn hope.

A Tragedy Indeed

However, there was also tragedy in the air, for I had orders to destroy all the liquor in the store, for which I had to get a fatigue party, and there were probably 20 or 30 cases of whiskey and other liquor which had to be destroyed. There were, in those days, teetotallers or prohibitionists available, so I had to take the best available materials. But I believe that I am truthful in saying that something very like tears were shed as the axes came down and smashed the bottles containing the precious fluid. It was a tragedy indeed - and all Salisbury aching for whisky, which was then worth about £6 a case, which was very dear for those days. The wounded having been attended to and placed in the hospital wagon, we were early awake the next morning and off, guided this time by Alec Nisbett and we headed west to get over to the Mazoe, as we had every reason to suppose that we should have had a warm reception had we returned by the road we came. It was a lovely ride over a very interesting bit of country, and we passed through kraals with only women in them. I think we only outspanned once until we got into the Mazoe Valley and then only for a short time. We well knew - at least those of us who knew the country - that it was odds against us getting up the Mazoe Valley without trouble and we had to trust to luck.

March in the Valley

We off saddled again just about sundown and had a good feed - no fires though and no lights allowed. Then about 9 o'clock we began our march along the valley, the same route which had been followed by the famous Mazoe Patrol only a fortnight sooner. It was all right until the Alice kopje was reached. Up to that point we felt we could move, but as everyone knows, once passed that there was little room to move - kopjes on the right and the swamp, hardly believable now, on the left. To have been attacked at any point between there and the Tatagura meant a very bad time indeed and some of us, at all events, well knew it. But all went well until we rounded the kopje at the Etna and the Vesuvius. Then the worst of all things happened, the wagon broke down. I cannot now say how long it was before we got it mended, as silently as possible. I know that it seemed hours. What a sigh of relief we heaved when we moved on again and all was well for another half hour or more. We had to go very slowly and keep well in touch. Then we struck a snag at the very narrowest part of the whole road, about two or three miles from the Tatagura, we found that 20 feet or so of the road had been trenched and dug out ten feet deep and stakes erected underneath, the whole being covered with grass and earth, a regular Mashona trap.

Here was delay, as it was all but impossible to get the hospital wagon around the top, which was precipitous, and the lower side fell rapidly into swamp. Eventually we got it past on the lower side by carrying it on one side. Here the country improves to the Tatagura and we got over the stream safely. A horrid drift it was too in those days. We could hardly believe our luck and now we knew nothing could stop us as the country was beginning to open out onto the Mount Hampden flats. About a mile or so from the Tatagura, one single shot was fired, no more than a signal, doubtless. Then daylight came, some of the men rounded up a mob of Mashona cattle and we got to Mount Hampden about 7 or 8 o'clock, crossed the Gwebi, and it was here that we saw, I believe, more Mashonas then were ever seen during the whole rebellion. There must have been several hundred of them with eight or ten mounted men on the skyline to the West of Mount Hampden. Maclaren shoved his Maxim on the top of an antheap and let them have some at about 2,000 yards. They came no nearer.

News of the rescue

After breakfast, for which we all had a very good appetite, Snodgrass and myself were sent off with dispatches to Salisbury, to take in the glad news of the rescue. At the “Bubbies” someone had two or three pot-shots at us, but Snoddy and I were not taking any and we were very soon at the outlying pickets on the Count’s farm, now Avondale. We made straight for Judge Vincent’s house and there he was in the middle of the road, obviously from his expression, fearing the worst, staring at us two grimy ruffians coming down the road at a gallop. We yelled “Hooray” and that relieved him. A minute or two afterwards we were joined by Frank Mack, of the French South Africa Development Co. and five minutes after that Snoddy and I were quaffing the very best Pommery, very pleased with ourselves. But they did not keep us long. There were no telephones in those days, and we were hustled off to tell the joyful news to the laager, which we reached just as everyone was being allowed out, somewhere about 10 o'clock.

The Commodore

The two ladies who took me home that day and gave me a really hot bath, are still alive and if they read this, they will know that I never enjoyed a bath so much in my life. It is not too much to say that this most successful patrol did much to reassure people and entirely altered the situation. It was now realised that one or two armed men might with impunity ride through Mashonaland, that the Mashona would not attack even a small body of troops and that it would not be long before communications were established. There is no doubt that the man to whom this was due (though I have not seen it anywhere referred to) was Captain AHF Duncan, better known to old hands and intimates as the ‘Commodore’ who put heart into us at a critical time by his example in riding from Matabeleland to Salisbury through a hostile country, accompanied only by one man.[xvii]

If I am to conclude anything from the accounts, it would be that the military differed greatly with the civilians when it came to sending out rescue parties; that within living memory of the incident, people felt Duncan was a real hero; that a single medal for the whole campaign devalued acts of individual heroism; and that the mass sighting of Mashona warriors, which no doubt included some Matabele insurgents and other renegades, may indicate they were planning their own assault on the capital. It remains unfortunate we know of no military plans, or strategy for finishing off the settlers. Given 10% of the white population was killed, the chances were good in the early days of the uprising. Broadbent says in his account they had been told by their attackers that Salisbury had been overrun and all the whites killed.”

The Tafuna Hotel and Roy Welensky

The area now called Shamva was in the 1890’s known as Abercorn after the 2nd Duke of Abercorn, then Chairman of the BSA Company, but the name was altered to avoid confusion with postal addresses in the Abercorn District (now Mbala) in Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia. At the time, local people wanted the area to be called “Tafuna.” The name Shamva is derived from Tsamvi, a tree common in that region and was named after the Shamva Mine, which was registered in 1907 on the site of the 1895 Lone Star Hill claims.

Eric Rosenthal in his comprehensive survey of the contribution made by Jewish citizens to this country, notes that the young Roy Welensky who eventually became the second and last Prime Minister of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, worked at the Tafuna Hotel. Roy had an Afrikaner mother and a Lithuanian Jewish father, and described himself as "half Jewish, half Afrikaner and 100% British.”

In 1920, a 13 year old Roy Welensky found his first job with an auctioneer with the unmistakable name of Ikey Cohen. This was followed by another with Sam Gruber, manager of the famous old firm of Charelick Solomon & Co. Merchants; they were Romanian born Jews and leading members of the Salisbury congregation. Mr. Gruber described Welensky when he first met him as: “a husky young chap, with broad shoulders and an unusually big stomach. Without a jacket, he did not look very presentable, and in his father’s footwear he looked anything but a Puss in Boots. I told him to sit down and, as it was my tea-time, to have a cup. He told me it was very different kind of reception to what he had received elsewhere. I asked him what work he wanted, and he quickly said: “Anything, so long as I can earn a living”. I gave him a start and he got along very well, but in those days, he did not seem able to settle down anywhere long and after a time he left me.”

Welensky’s next job was working on a small mine where he met Isaac Benatar, a member of the Sephardic group, and three years older who had only arrived in the country in 1922. He said “Roy was about 16 at the time. Not long before I had come to Salisbury from my native island of Rhodes to work for a cousin of mine in a trading store in Glendale. I persuaded my cousin to take Roy to assist me, because there was far too much for one to do. The store was a small tin shack that could be shifted to another site if trade went sour on us, and there we sold everything from a needle to a side of sheep. Most of our customers were Africans, with whom Roy got on very well. They admired his huge frame and his gentle, considerate way. For this reason, I gave him the counter job, while I delivered goods. Both of us slept in a little outhouse tacked on to the back of the store, and I could not help noticing how limited was Roy’s personal wardrobe. He had two well-worn shirts, three pairs of stained and tattered shorts and no pyjamas, he never in fact, owned a pair of pyjamas, or slept between sheets, until he got married! He just used to strip and pull the blanket over him and he turned 20 before he wore a jacket”.

It soon became plain that Roy was growing restless again and he took on the post of a barman at the nearby Tafuna Hotel, where the main clientele were miners from the Shamva Goldfield. “Every month they used to get 36 hours leave; 30 of which they spent at the hotel blowing their pay on a binge. But Roy had no throwing-out to do: his presence was enough. They just drank and horsed about, until they collapsed over a table in a drunken sleep. Roy then slung them one by one over his shoulders, carried them to a rondavel and left them to sleep it off. Most of his pay of £7 a month went back to his old father in Salisbury. In his spare time, Roy went into town with his brother, Isaac, finding plenty of opportunities to use his fists.”

His father, Michael Welensky, had a humble job as “Wacher” or Watcher over the Dead for the Jewish Congregation, who paid him enough, combined with his son’s remittances, to keep going. Eventually he found a haven in the Jewish Aged Home, Johannesburg, where he died and where a friend found his only belongings, an old tin box containing “good for’s” representing loans of £14,000 which he had made during the course of a long life, in his generous moods, and which had never been repaid!

Roy himself had by this time found a post at Bulawayo, as a locomotive fireman on the Rhodesia Railways, where he shed, so he said, 70 lbs of surplus weight! His wages on the footplate of £23 a month for a working week of 100 hours were still supplemented by boxing purses, taken in the tougher parts of Bulawayo and Salisbury.

What happened to the survivors?

There is little information about the survivors of the siege of Deary’s Store at Abercorn, although I did establish from Mrs Holland’s records at the Loyal Women’s Guild (LWG) that their leader, Edward Charles Broadbent, was later employed as a telegraph linesman building the transcontinental telegraph line to Nyasaland (now Malawi) and is recorded as having died on the 20 April 1897 at Inyanga, probably of malaria. His grave marker is described as a wood cross with his details recorded on a tinplate. The LWG provided a Pioneer memorial cross for him of the same type given to John Fletcher and I am grateful to Kevin Atkinson for supplying the photograph below of Broadbent’s actual memorial cross at Nyanga. Note the date of death on the memorial is recorded as 2 September 1898. Clearly the LWG did not have particulars of his death to give to the Gregory Iron foundry in Cape Town and the details punched on the memorial cross with a nail were probably made by one of his friends.

Acknowledgements

Col. A.S. Hickman. The Siege of the Abercorn Store. Rhodesiana Publication No. 9 December 1963 P18-27

The ’96 Rebellions. The British South Africa reports on the Native disturbances in Rhodesia, 1896-97. Schedule F. Rescue of the Abercorn party. P98-100

E.E. Burke. Mazoe and the Mashona Rebellion, 1896-7. Rhodesiana Publication No. 25 December 1971.

J. Waters. A Forgotten Story of Valour: The Abercorn Store rescue revisited. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 39, 2020. P109-118

E. Rosenthal. Rhodesian Jewry and its Story. Part V. (www.zjc.org)

T. Rolfe for details of their military records

Notes

[i] Col Hickman states the patrol was under Mr AHF Duncan, the acting Administrator for Southern Rhodesia, then standing in for Dr Jameson, but this appears incorrect from details in the newspaper articles as he greets the patrol on arriving back in Salisbury

[ii] Col Hickman omits Snodgrass and Maclaren, but they are included in J.T.-J’s article ‘Reminiscences’ and he actually rode with the patrol

[iii] Col Hickman states 8am

[iv] John Rowlands died the day following the rescue, so six survivors were brought into Salisbury

[v] 11 July 1896

[vi] See the article Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and Cemetery under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[vii] See the article The June 1896 Mazoe Patrol skirmish with detailed accounts from those besieged and their Mashona attackers under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[viii] Lomagundi

[ix] He had come from Charter

[x] Hardly – Duncan arrived in Salisbury on 10 July and the patrol left for Abercorn on 11 July

[xi] Mr Duncan did not accompany the patrol as the author states the first thing they did on arriving back in Salisbury was ride to Mr Duncan’s house and inform him of their success

[xii] to Shamva

[xiii] 11 July 1896

[xiv] 8am

[xv] Cape Mounted Riflemen (1827-1870)

[xvi] The para-military Frontier Armed and Mounted Police (FAMP)

[xvii] As noted, Duncan had come into Salisbury from Charter accompanied only by Evered his servant