Lalapanzi

- The village name means “to lie down” and may have been given to the place by transport riders in early days because the oxen drawing the wagons travelling from Fort Charter to Gweru often got bogged down in the vleis during the wet weather. They sank up to their bellies in the mud and it looked as if they were lying down - hence lala - to lie and panzi - down.

- The town itself was established in 1908 when a railway siding was opened on the Gweru – Masvingo railway line when the chrome from the nearby mines in the Great Dyke was loaded at the siding.

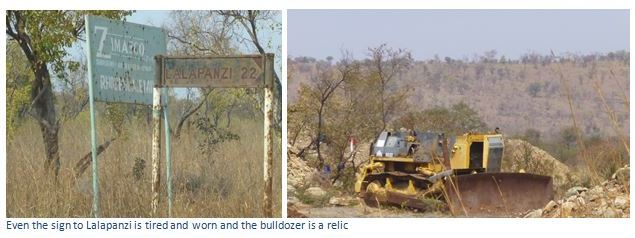

From Mvuma take the A17 to Lalapanzi. The A17 turnoff is on the Masvingo side (i.e. south of Mvuma) 9.6KM ignore the turnoff to Sebakwe Recreational Park and Kwekwe, 39.2 KM turn right for Lalapanzi.

From Gweru take the A17 east out of town past Thornhill Air Base and Wha Wha; 43.7 KM reach Lalapanzi.

GPS reference: 19⁰20′11.15″S 30⁰10′36.86″E

Lalapanzi is a small village in the Midland province in Zimbabwe. It straddles the Great Dyke, a mineral-rich geological formation that runs from the north east of Zimbabwe to the south west through the centre of the country.

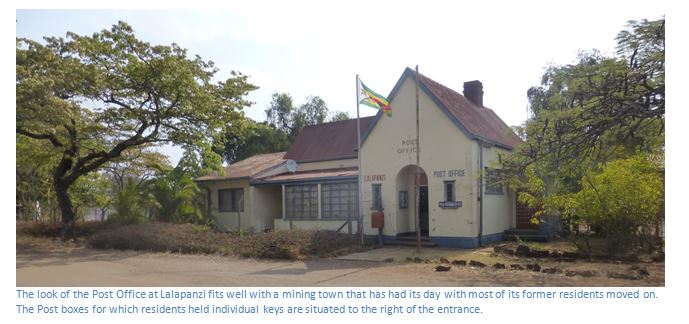

The faded look of the Post Office at Lalapanzi fits well with a mining town that has had its day with most of its former residents moved on. The Post boxes for which residents held individual keys are situated to the right of the entrance.

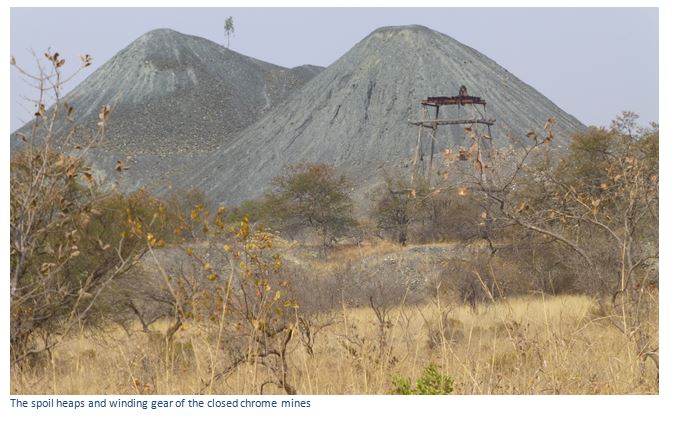

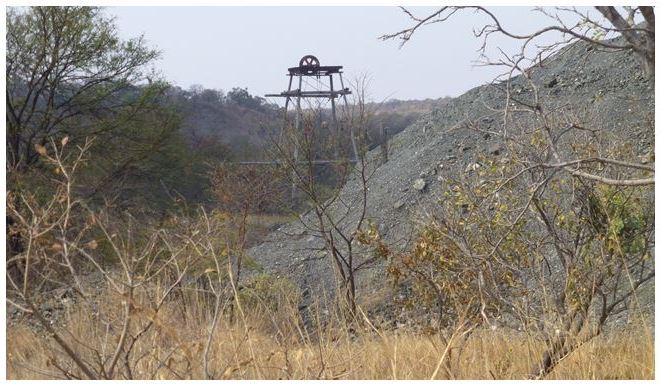

Built around the chromium mining business, the largest mines were operated by Lonrho (London Rhodesia Company), which has since given up its stake, and Zimasco (Zimbabwe Alloy and Steel Company) which is largely dormant. Starting in the 1990’s smaller, independent miners have been mining the chrome largely in open-cast operations which have left open pits and many artificial mountains made from the spoil heaps of waste rock. Very little land reclamation has taken place; mined out areas have been simply abandoned.

Today, the chromium mining is again being operated by big companies; 70% of Zimbabwe’s chromium mining is owned by two companies, Zim Alloys and Zimasco, plus according to a Zimbabwe Government report ( the portfolio committee on Mines and Energy October 2013) there are eight Chinese companies mining chromium in Zimbabwe at the moment, but only one has documentation to substantiate mining rights.

Large bulldozers are brought in to dig and rip up areas of the ground to expose the chromium rich rock lying just below the surface. Local labourers break up the rocks with picks by hand and lay it out in pegged out piles that are measured amounts. Trucks belonging to the big companies then collect the piles and the workers are paid for the amount they have dug, then the ore is removed for processing.

Most of the chromium mining in Zimbabwe is open cast, there is very little regulation enforced and no reinstatement of the land afterwards, which is left scarred by the process and also left polluted. The majority of the chromium ore deposits are along the Great Dyke in Mutorashanga, Chegutu, Kadoma, Kwekwe, and Lalapanzi.

However, since the commodity price collapse of the 1990’s, Lalapanzi has largely become a ghost town.