Penhalonga

- Apparently, the name Penhalonga comes from the Shona word ‘panaronga’ meaning the place that shines and not, as was believed, from Portuguese penha meaning “rocky mountain” and longa meaning “long.”

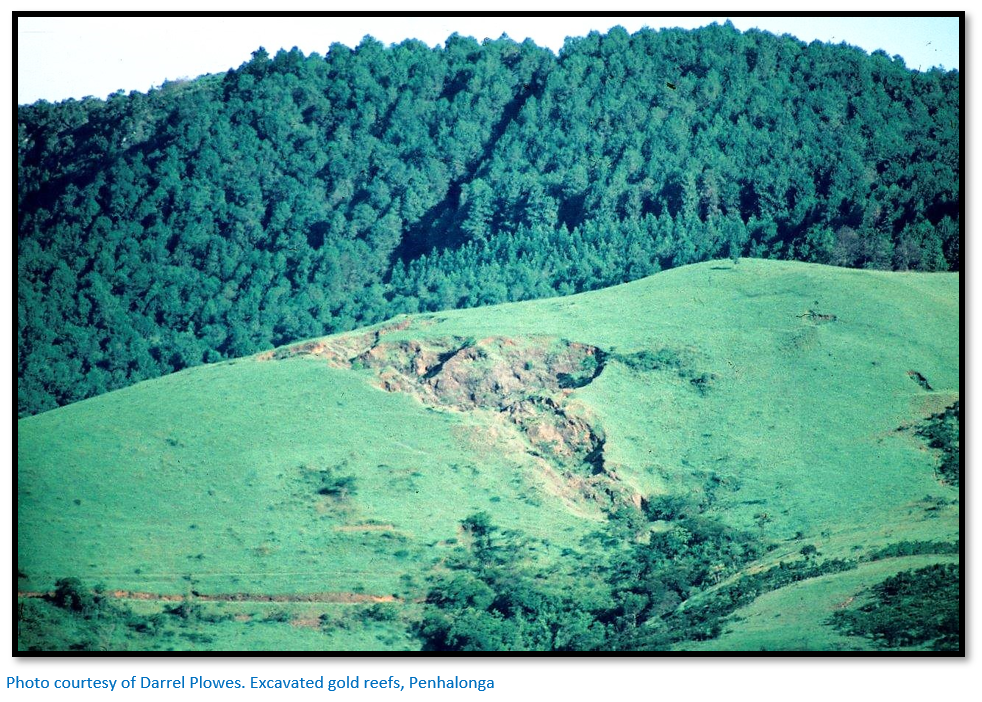

- Gold mining has been carried out in the area around Penhalonga for a considerable period of time and the Mutare River (‘river of metals’) that flows down from the Penhalonga Valley had rich alluvial gold in its gravel beds. There is plenty of evidence of ancient alluvial gold workings along the Mutare and its tributaries, the Imbeza and Tsambe Rivers.

- The Manyika panned the Mutare River for gold which they traded with Swahili merchants at Sofala and made it into a flourishing and rich city-state long before the Vasco Homem, the first Portuguese visitor, Vasco Homem, arrived in the present-day town of Manica in 1575.

- In the early 1900’s over 160 gold mines were pegged and worked, most very briefly, although the Penhalonga, then the Redwing and now the King’s Daughter Mine, operated by Metallon, continues today.

- The village grew up around the mines, but today only the Police station and Post office and a few old stores remain to remind us of what was once a thriving and prosperous centre.

Coming from Harare pass the A15 turn-off from the A3 main Harare to Mutare Road, 2.4 KM turn left before Christmas Pass at the petrol station on road signposted for Penhalonga, 7.2 KM continue past the Fairbridge Road going to the left, 8.9 KM turn right for Penhalonga

GPS reference: 18⁰52′50.27″S 32⁰40′39.20″E

In 1888 Baron de Rezende, the Mozambique Company’s Director of Operations on Africa approached James Henry Jeffreys, a British mining engineer to lead an expedition into Manicaland. Jeffreys and chosen numbers of the expedition left Barberton for Delagoa Bay. Here he met Mr. Maritz, who asked him if he and some others could join his party, as he had also obtained a concession. They sailed on S.S. Carland, for the island of Cheloane, situated about 55 miles south of Beira. From there they sailed on a small tug for Beira. After one night on the tug he said, "The little craft also carried a cargo of cockroaches and a fair amount of other undesirables."

With the onset of the rainy season they needed make a start as soon as possible; Baron Rezende decided to accompany them into the interior. Native carriers had to be obtained to carry provisions, made up into 60 lb. parcels, but as Chief Gungunyana was raiding, carriers were afraid to go into Manicaland.

Fortunately, a small paddle boat built in Yarrow on the Thames arrived in Beira. It was consigned to the Companhia de Mocambique for use on the river Pungwe - Busi. After three weeks in Beira completing arrangements, they took to the paddle boat towing two lighters with their goods. It had been arranged that two hundred carriers would join them on reaching Manangora Island.

0n arrival, there was a delay, as no carriers turned up. After two weeks the party struck camp and continued by the same paddle boat on its next journey to Mapanda. Then a runner arrived with a message that on account of Gungunhana’s marauding party into Manicaland, it was advisable not to continue. The disappointment was great, but Rezende and Jeffreys decided to continue on alone. The rest of the party decided to remain at Gorongoza village (now a game reserve) for the end of the rainy season.

Jeffreys and Rezende could only muster nine carriers, four of whom were personal servants and out of that number three of them deserted, being terrified of meeting Gungunhana’s Impi and often they passed kraals deserted by the Manicas. Jeffreys and Rezende progressed as best they could to Macequece. Fortunately, the Portuguese had obtained a promise from Gungunyana that he would not interfere with Europeans which is why they were not molested.

In view of the heavy rains, Jeffreys and Rezende stayed at the old fort of Macequece, which was unoccupied, which gave them the opportunity of investigating its past history, today it is known as Manica. In its early days, as Chipangura, it had been a main centre for marketing gold and slaves, before they were dispatched to the coast at Sofala. Whilst cleaning up inside the fort, they came across nineteen human skulls which crumbled away when exposed to air.

Rezende and Jeffreys explored as far as Chief Mutasa’s, by way of the Revue River and what is now known as ‘the Divide’ and Penhalonga. Their food ran out as could not be replenished as Gungunhana’s raiders had stripped the country of all food. After their months of hardship and weak with malaria, they were saved by a French Engineer who arrived by canoe with quinine. When fit again, they walked to Mapanda where the engineer had left his steamer, and so were able to return to Beira and sent word for the remainder of the party to travel to Macequece.

Jeffreys and his party then started prospecting and by October 1889 that they discovered and pegged claims on two quartz outcrops with ancient workings and visible gold, the future Rezende and Penhalonga Mines, the latter named after Count Penhalonga of Lisbon. Both mines were a great financial success and produced a good quota of gold for many years, but unfortunately little of those prosperous days remain.

After pegging the claims, Jeffreys returned to Barberton leaving men to develop the site. His syndicate sent him to London, and he formed a syndicate in Paris to fund the Penhalonga mine. In 1891 Jeffreys returned with another party of ten whites, after engaging a steamer to take them up the Pungwe from Beira. "This country was then flooded" he remarked "from the Zambezi to the Pungwe." Of the 1888 party only two men were still alive - Mr. Maritz and Mr. G. Arnold. Of the second party none remained.

In 1887 Col. Paiva De Andrade, a Portuguese explorer, obtained a mining and commercial concession in Manica and formed two companies which later amalgamated into the Mocambique Company which could be described as being similar to Rhodes' British South Africa Company which had identical objectives. The Mocambique Company gave out several sub-concessions and in January 1889 the manager of the company, Baron de Rezende, with a British miner J. H. Jeffreys and a number of other prospectors succeeded in reaching Macequece or Massi-Kessi (now Manica). Jeffreys and the Baron pushed on to Makaha, a place south east of Mtoko.

The discovery of gold could not be kept secret, and soon a company of prospectors from Barberton in the Eastern Transvaal arrived and proceeded to the Penhalonga valley where they investigated the alluvial workings left by the ancients. The name of the valley and its mine was in honour of Count Penhalonga, who with Baron Rezende first formed the Mocambique Company. The place was first spelt 'Panhalonga’ but was changed to the present form on April 1st, 1904. Baron de Rezende and Jeffreys returned to the area in 1889 and Jeffreys pegged the Rezende and Penhalonga mines before leaving for England in November. More prospectors arrived the following year but found most of the likely spots already pegged.

In June 1890 the British South Africa (B.S.A) Company’s Pioneer Column entered Mashonaland. The first Administrator Archibald Colquhoun left the Column at Fort Charter with nine others and proceeded to Manicaland to conclude a treaty with Chief Mutasa, the paramount of the Manyika, who had already been subjected to similar pressure from the Portuguese. A treaty was signed with the Chief on September 14th and his country came under British influence. The Portuguese disputed the validity of the treaty, which resulted in the arrest of Col. Paiva de Andrade and Baron de Rezende and their expulsion from the country via Fort Tuli. The Portuguese finally recognised the treaty between Mutasa and the B.S.A. Company and the boundary between the two territories was settled in June 1891. The rights of the Mocambique concession holders were recognised and their claims converted into Rhodesian claims in about 1891 after a mining commissioner was appointed at Umtali.

Rhodes visited the site himself in October 1891, and he was met at the border by Jeffreys who showed him some of the samples he had taken from the Rezende Mine. A plaque still marks the spot where Rhodes entered the country from Beira. The mining conditions were very difficult at first because of poor transport, tsetse fly and cattle disease, but the railway from Beira reached Umtali (now Mutare) in 1898 enabling mining machinery to be imported much more cheaply and this aided mining operations considerably.

In 1894 Edward Knight, a very-widely travelled correspondent for the Morning Post and The Times visited the new territory of Rhodesia and his assessment of the country, which was very favourable to the British South Africa Company, was presented in a series of articles written for The Times and later appeared in book form under the title of Rhodesia of Today. He reported the following registered Mashonaland gold claims with the highest number in Manicaland:

Mashonaland Gold claims in August 1893 | ||

Salisbury (Harare) district | 3,560 | |

Mazoe (Mazowe) district | 6,510 | |

Lomagundi district | 2,600 | |

Umfuli (Mupfure) district | 7,590 | |

Victoria (Masvingo) district | 6,150 | |

Manica district | 10,150 | |

36,560 | ||

He travelled through the best known and most developed Mashonaland goldfields which he describes as those in the Victoria (Masvingo) and Manica districts where he visited the principal mines. The Penhalonga goldfield is described as extending sixteen kilometres from west to east before passing into the “debatable land” whose ownership is still undefined as at that time the British-Portuguese Boundary Commission had not announced the final border line. At that time, after the disruption of the 1893 Matabele War, the mines were being vigorously developed and he believed the wealth of the district would soon be proved to the world with a considerable output of gold. He says the “ancients” i.e. pre-European miners thought highly of this gold belt as all the valley bottoms had been turned over with alluvial workings, whilst the hill-sides were full of reef workings.

Knight was positive about the Rezende Reef owned by the United Goldfields of Manica Company which had developed a series of adits into the reef and also the Penhalonga Reef, pegged by the Penhalonga Gold Mining Company. He was guided into the main adit of the Penhalonga Reef by candle-light to view the unique character of the quartz which was highly mineralised and studded with crystals of red lead chromate. He says the walls glowing and flashing with blood-red crystals made a curious and beautiful appearance.

Rezende Mine

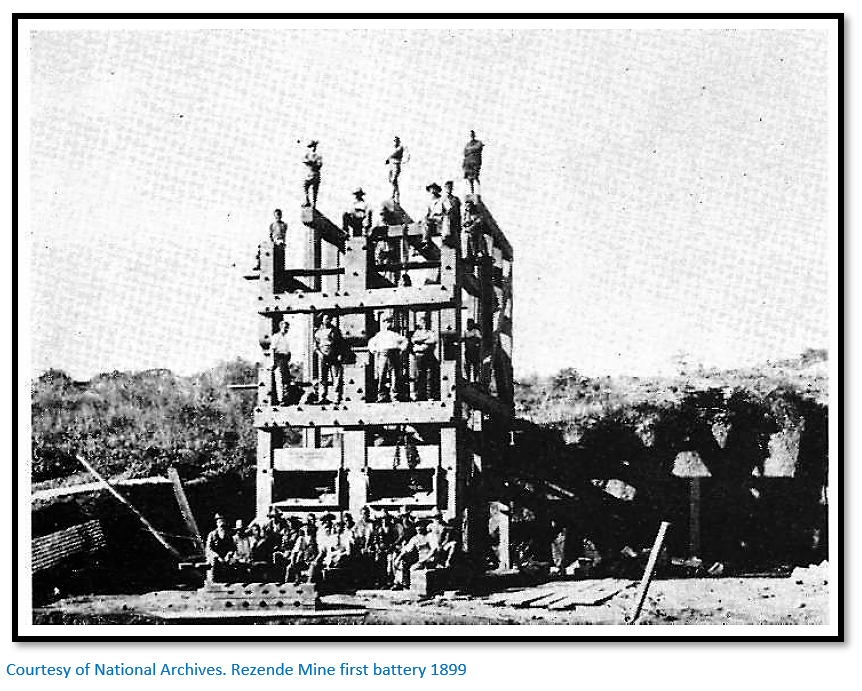

The original Rezende Concession was sold to the United Goldfields of Manica Limited, who carried out development in the mine to a depth of about 80 feet from adits in the bank of the Mutare river. The Company went into liquidation in 1898 and a new Company known as Rezende Mines Limited was formed with a share capital of £150,000. Shares to the value of £13,500 were issued to the BSA Company in lieu of royalty and a ten-stamp mill, crusher and cyanide plant and other plant was shipped from England and was commissioned in July 1899.

From the first ore treated 12 kilograms (424 ounces) of gold were recovered, which represented an average of 42 grams (27 dwts) per ton. However soon after commissioning a disastrous fire destroyed the mill house and seriously damaged the plant which was not insured. A £10,000 loan had to be raised and the share capital was increased to £175 000, but only £156 000 was subscribed. The mill was re-commissioned in 1900 and ran uninterrupted thereafter for many years and an electric power plant, driven by water from the Umtali river, was built at the bottom of the Penhalonga waterfall.

A fall in the ore grades and a shortage of power to operate the 20-stamp mill and cyanide plant. the Rezende Mining meant that by 1904 the Company was in financial difficulties. In May 1905, a new Company, Rezende Limited was formed, to be jointly administered with the Penhalonga Mine, with both mines being supplied with electricity from a water-powered station on the Odzani river. The mill capacity was increased to 30 stamps and additional cyanide and crushing plant added. The main shaft was re-timbered, but electrical power continued to be insufficient to supply compressed air for rock drilling. Arrangements were made to obtain compressed air from the Penhalonga Mine, but the pumps driven by compressed air could not keep the mine dry.

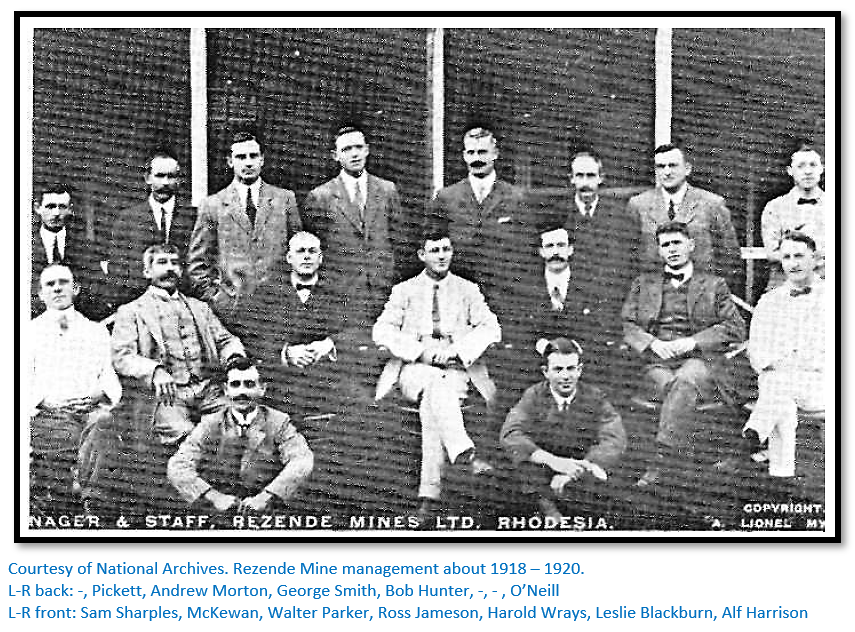

The results to the end of 1917 were disappointing owing to a shortage of manpower with the outbreak of WWI. At the end of 1917, control of the mine passed to Sir Abe Bailey and the company offices were transferred to Salisbury. During the influenza epidemic of 1918, operations on the Rezende Mine were seriously interrupted; 3 Europeans and 50 Africans died, while 650 Africans while most of the workforce of 650 returned to their homes. But in spite of these problems in 1920 the mine made a profit of over £40,000 and declared a dividend of 20%. This was largely due to the high gold values rich from the eastern section reaching the mill.

The dividend was increased to 40% during the following year and continued at the same level until 1923 when the share capital was increased to £150 000 by the issue of £30 000 in the form of bonus shares. The tenth level was completed in 1925 but grades were low and from this period onwards profits began to fall, due to worsening grades. Despite exploratory drilling the geologists concluded that the ore shoot had ended and that the reef had run out and all work below the tenth level was stopped.

Between 1918 and 1935 profits totalling more than £1,460,000 were made with regular dividends paid. In 1929 options were obtained over the Reliance and Monarch Gold Reef claims in the Umtali district, but these were relinquished two years later after drilling failed to reveal any new ore bodies. At the same time doubts about the Rezende's ore reserves began to surface, but in 1933 boreholes were sunk to intersect the reef in depth and the promising results led management to start a new shaft to the North of this outcrop. However at a depth of 215 metres (710 feet) the shaft began to drain the water from the old mine levels, to add to the problem methane gas and carbon dioxide came out with the water forming dangerous and explosive mixtures within the pump chamber. Mining proceeded cautiously and by 1935 the shaft was below the old No. 8 level and an aerial ropeway was constructed to bring the ore to the Rezende Shaft.

Two further boreholes were drilled on the Penhalonga claims and struck a rich reef at 350 metres (1,141 feet) and 450 metres (1,469 feet) The Penhalonga Mine workings were re-opened and development began again. As part of this development the adjacent Liverpool Mine and King's Daughter claims were acquired.

New reserves were located on the Rezende Mine on the thirteenth and fifteenth levels and to meet the increased capital expenditure for this new development, the Company was again reconstructed and the capital increased. The new ore bodies revealed good values and in 1937 a dividend of 100% was paid.

During WWII conditions made operations for the mining industry difficult and costs began to rise, exacerbated by a shortage of experienced miners who had gone to the front. The mine was then operated with a battery of 40 stamps and two ball mills. Profits began to decline and in 1946 the Company made its first loss which amounted to £2,500 but the financial position improved in the following year, due mainly to the saving in costs with the closing of the Redwing section.

The Rezende Mine operated until 1955, when it closed. During its life it had produced more than £7 million worth of gold. The Rezende was a very 'wet' mine and was always in danger of being flooded, but was equipped with many pumps which pumped out about 455,000 litres (a million gallons) of water every day from the mine. The Rezende Mine is still being worked as the Redwing Mine today.

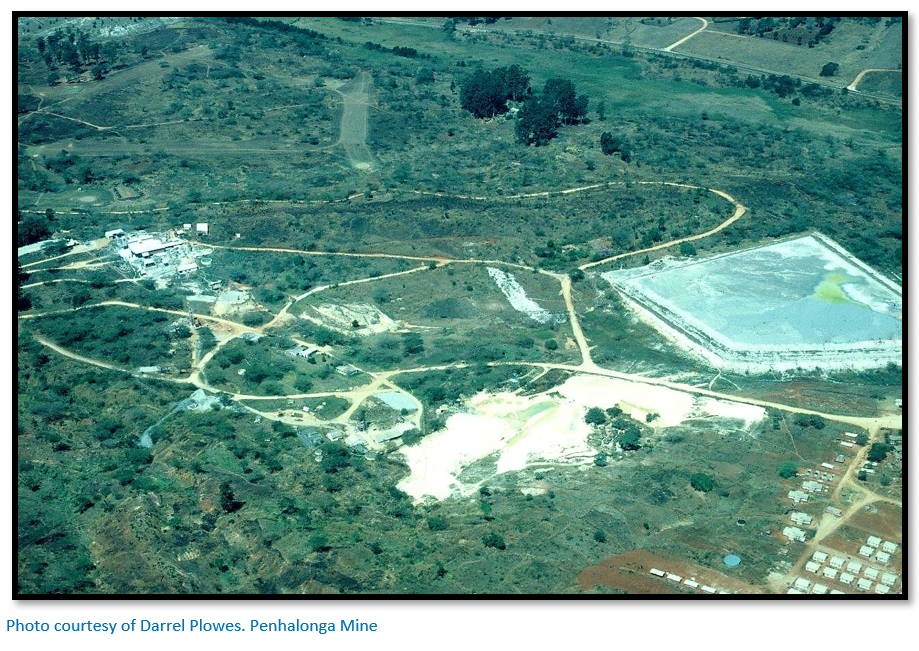

Penhalonga Mine

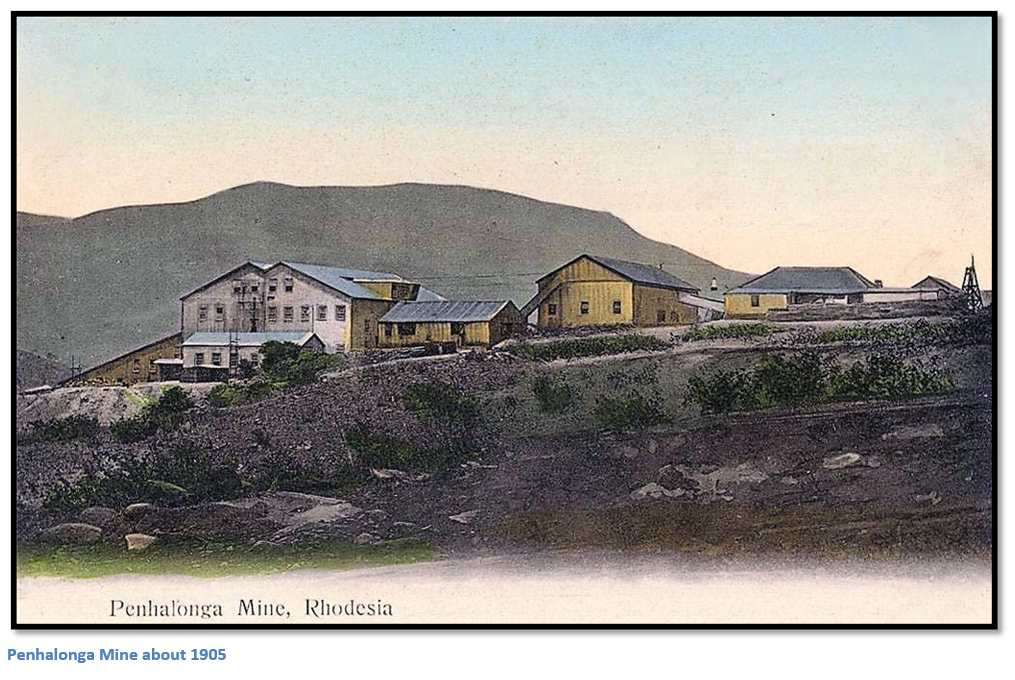

The first 5-stamp mill for the Penhalonga Mine arrived in 1895 by ox-wagon from the railhead of the narrow-gauge line when it was 75 miles from Fontesvilla on the Pungwe river. This mill acted as a pilot plant until 1903, when 50 stamps were installed by the Penhalonga Proprietary Mines. In its heyday, the Penhalonga Mine produced up to 650 kilograms (23,000 ounces) of gold a year, until it closed down due to rising costs. In October 1908 most of the staff were retrenched and the mill stopped in October 1908. In December, the shareholders called an extraordinary general meeting and decided to place the Company into liquidation.

A new Company was formed with an authorised share capital of £70 000 in one pound shares, of which 49,000 were issued, 27,000 being given to Rezende Limited shareholders, 13,000 to the Tulloch Goldmining Company for two claims, and the remainder to the B.S.A Company in commutation of royalty. Additional debenture capital was raised and the west shaft was equipped with a 60 hp electrical hoist and plant. However due to an insufficient ore stock it was only in October 1909, that the mill could be brought into operation. Further development took place and additional plant was installed, to increase the mine's output, but mining operations continued to be plagued by a shortage of power and labour.

The Penhalonga Mines Limited went into liquidation in October 1912, due to movement in the rocks below the fifth level, which made the rest of the mine inaccessible. The assets were taken over by Rezende Mines Limited for £30,000 cash and 18,000 Rezende shares. A new Company - Penhalonga Mines Limited - was formed by the Rezende Mines Limited, but there was a heavy write-down of the assets and the Anglo-French Matabeleland Company Limited which held many shares and debentures in the old company lost heavily.

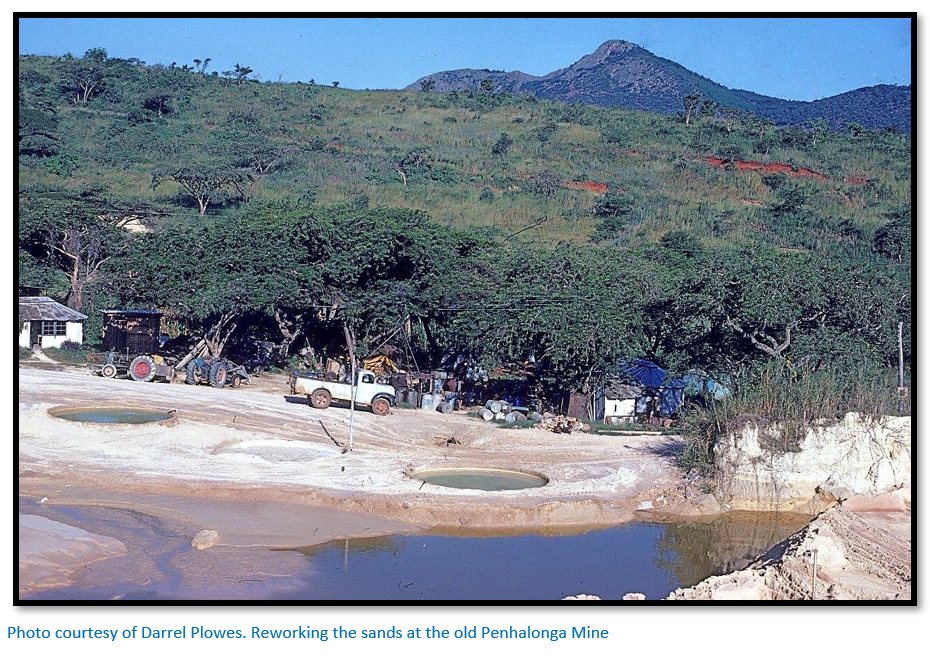

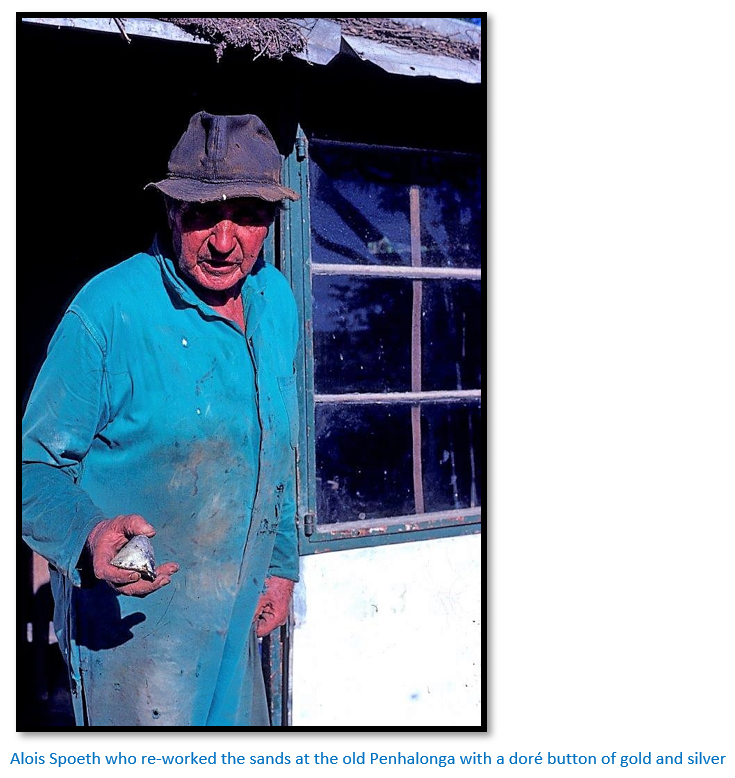

The Penhalonga mill continued to run until November 1914, when operations ceased. The sands dump was let out on tribute.

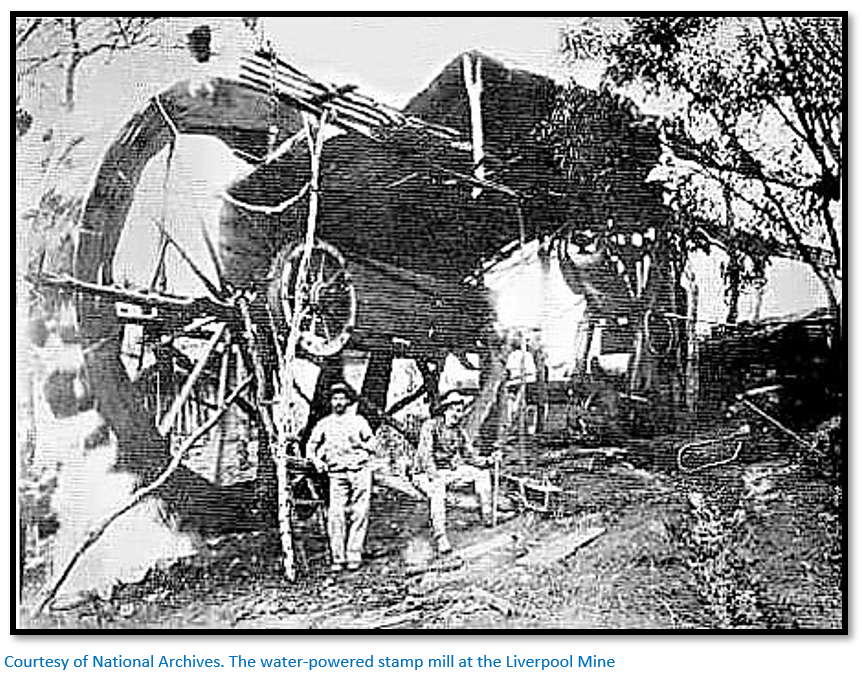

Liverpool Mine

A 5-stamp mill was brought from Benoni into Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) for Lobengula by the B.S.A. Company. It was brought to Hartley by ox-wagon but after the 1893 Matabele war it was dismantled and moved to Umtali. The mill was erected near Umtali and the site became known as ‘Battery Spruit.’ In 1895 the plant was moved to Penhalonga by Messrs. Bradley and Tulloch whose ingenuity was demonstrated by supplying power to drive the mill from a home-made undershot water-wheel made from empty whisky cases. Whisky at that time cost 7s. 6d. a bottle.

The mines created a boom during their heyday, but with their decline the small village of Penhalonga began to decline.

Today

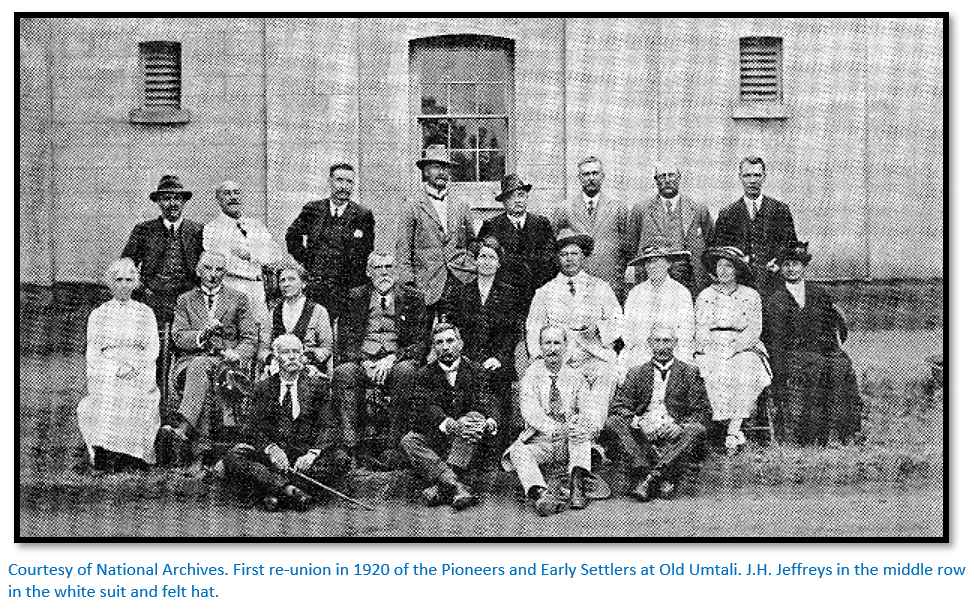

The village lies 17 kilometres north of Mutare in the valley where the Sambi and Imbeza Rivers join the Mutare River. Alluvial gold was being worked in the area in 1575 when it was visited by Vasco Homem. Political astute, Jeffreys decided to name the mining claims after officials from The Companhia de Mocambique, the company which possessed the trade concessions for Manica province. The first gold claim was named Penhalonga, after Count Penhalonga, chairman of the Mozambique Company. The Penhalonga Mine operated from 1897, in 1903 a forty-stamp mill was in operation driven by water power, eventually producing over 185,000 oz. (5.3 tonnes) of gold. Jeffreys however remained on at the mine and played a major role in its development, in fact, he even served as Mayor of Umtali and died in 1926.

Current issues – the new Penhalonga gold rush

The only significant gold producer today is the King’s Daughter Mine, operated by Metallon, formerly the Penhalonga and then the Redwing Mine. The other recent major company was DTZ-Ozgeo – a joint venture between the Development Trust of Zimbabwe and Russia’s Econedra – that was forced by the Environmental Management Agency (EMA) to stop its operations in 2013, due to an outcry from the local community regarding the environmental catastrophe it was causing along Mutare River.

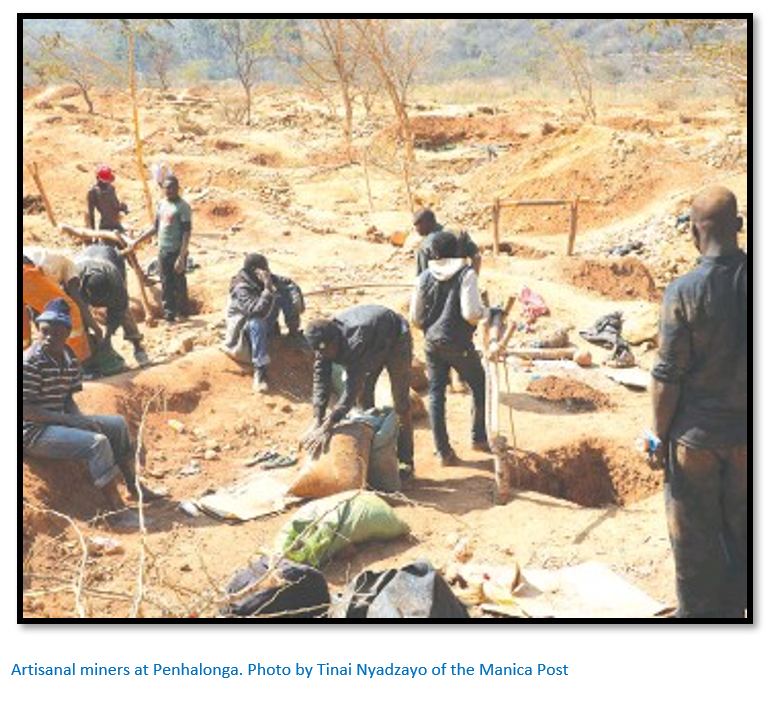

However, there are also dozens of small-scale miners operating around Penhalonga and Tsvingwe using mills that use mercury and cyanide to recover gold. In addition, hordes of illegal gold panners have arrived in Manicaland following rumours of gold deposits in the area. This is a result of the poverty and lack of job prospects affecting many unemployed young people like 25-year-old James Bhunu who joined the rush. “I only want to survive and fend for my family. I’m here because of hunger, because there is no food for my family,” he said. Bhunu is one of many ‘Makorokoza’ (artisanal miners) and he said that in a ‘lucky’ week, he could make more than $500 from selling gold.

The discovery of rich ore deposits in Penhalonga is bringing relief to the local community where most of the people are unemployed. Timothy Mutungagore, a community leader said Saungweme Mountains and Mutare River have been besieged by the illegal panners. “Before, there was a lot of gold and few people knew about it, because there was food and people didn’t care about gold. Now, because there is hunger and unemployment, people come from all over the country to mine.”

However, the illegal gold panning has tragic consequences. In 2016 eight illegal gold panners died after being trapped in their shafts and in March this year, six illegal gold panners were trapped after a mine tunnel they were working in collapsed and buried them alive in the Saungweme Mountain area. Six other illegal panners who were in the same shaft managed to escape with help from Redwing Mine’s emergency team.

The community’s hopes rest on a mining law hoping to attract investment and development. “What we need are international investors to come in and mine for gold so the community can benefit,” said Chief Mutasa. According to police, an estimated 400 illegal gold panners are refusing to vacate Mutare River banks and Saungweme Mountain in Penhalonga. The panners have compromised the safety of the river by digging deep trenches and causing massive soil erosion.

But the Manica Post interviewed local artisanal miners who said: “We will work as syndicates of 10 as they (Government) said and we will supply Fidelity Printers and Refinery. We don’t want this system of bringing truckloads of police officers to beat us with baton sticks. We don’t want that. We have kids in schools, we pay rent, we pay municipal bills like water and electricity. All these elderly women who frequent the area is because they want to send their children to school. They said we must be given the opportunity to voice our concerns and this is democracy.”

Additionally the local community maintains that the seizure of their land by small-, medium- and large-scale gold mines has affected our traditional way of life and our livelihoods. The small amount of arable land, which has sustained local families for generations, has suddenly become private property and they became subjected to trespassing laws that carry sentences of imprisonment or fines or both. As the arable land was lost, they were being transformed from peasants to labourers or unemployed.

References

R. Cherer Smith. Rezende Mine. Rhodesiana Publication No. 34, March 1976

Manica Post 7 September 2018. Please don’t chase us away: Artisanal Miners