Zimbabwe’s artisanal miners, popularly known as makorokoza, risk their lives to make a decent living

Sources

This article is a very abbreviated summary from the following publications which readers may well want to follow-up. They are Follow the Money: Zimbabwe. A Rapid Assessment of Gold Supply Chains and Financial Flows Linked to Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining in Zimbabwe written by Marcena Hunter with help from Mukasiri Sibanda of the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (ZELA) with funding from United Nations Industrial Development Organization and The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. (March 2018 www.unido.org/Zimbabwe ASGM_28.04.18)

The above report used results from the excellent and comprehensively researched 2015 Pact report A Golden Opportunity: Scoping Study of Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining in Zimbabwe authored by Peter Mudzwiti, Norman Mukwakwami, Dr Motive Mungoni, Itai Madzivaidze that used information based on questionnaires and surveys in the Kadoma and Shurugwi districts of Mashonaland West and Midlands provinces respectively.

Any reader wanting to know more about small-scale and artisanal mining is advised to start with the above although some details will have changed since they were published.

The critical role of artisanal miners (ASM) in Zimbabwe today

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) defines artisanal mining as: “formal or informal mining operations with predominantly simplified forms of exploration, extraction, processing, and transportation. ASM is normally low capital intensive and uses high labour-intensive technology. ASM can include men and women working on an individual basis as well as those working in family groups, in partnership, or as members of cooperatives or other types of legal associations and enterprises involving hundreds or even thousands of miners.” (OECD 2016)

Zimbabwe’s economy is broken except for pockets of activity

Zimbabwe’s economy has been in desperate straits for a long time now; this is evident in any of the small towns dotted around the country which have been hit by endemic unemployment, the chronic cash and fuel shortages and the ever-rising inflation rate which hit 838% in July 2020.[i] Unfortunately the country's economic crisis is expected to continue deepening amid a weakening currency on the back of the global covoid-19 pandemic, together with the government's inability to deliver economic reforms and persistent shortages of food due to successive poor harvests.

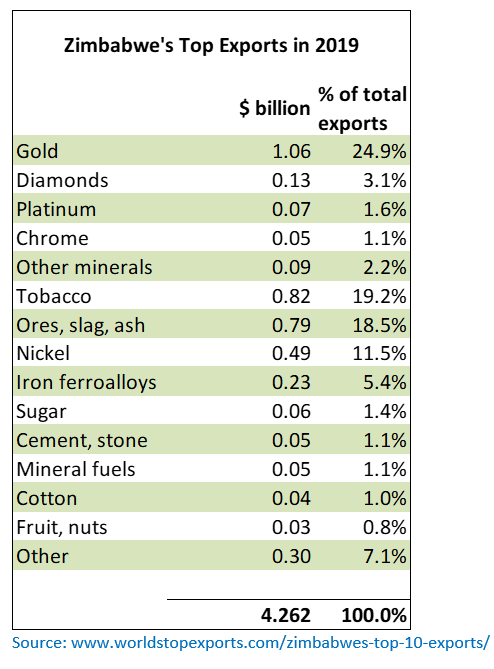

However some small towns are experiencing what feels like a mini-boom and inevitably they are found on the fringes of the country’s gold-belts. That these young men and women are spending their hard-earned money at the various small businesses create an illusion of a new gold rush which has become a vital component of Zimbabwe’s economy.[ii] Gold is now the single largest currency earner closely followed by tobacco.[iii]

Gold exports are critical for Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe has a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of approximately $40.3 billion[iv] with exports now forming 10.6% of the total GDP and with a population of 14.645 million in 2019[v] exports represent $291 for every Zimbabwean with gold exports averaging $72 per person.

Clearly the economy is becoming increasingly dependent on its mining industry with gold leading the charge and this has never been more apparent to the men and women on the bottom rung of the economy who face stark economic choices in order to provide food and shelter for their families. Estimates of Zimbabwe’s unemployment rate are as high as 95% but this includes the proportion of people in the country who are working in the informal economy, which is characterised by low wages, poor working conditions, little or no social security and representation.[vi]

With high unemployment figures and no prospects of earning a living except by subsistence farming thousands of youths whose access to education has been disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic and women who in the past have been prevented from mining are joining men in an exodus from the towns to the gold-mining regions.

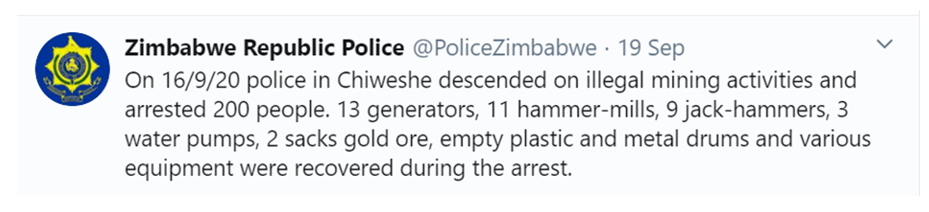

Artisanal miners are still being harassed and arrested

In August 2020 Stephen Tsoroti and Ankita Anand visited the artisanal miners on the eastern shore of Mazowe dam near Harare – this was the chosen site of former first lady ‘Gucci Grace’ Mugabe who used heavily armed Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) who came and burnt down houses belonging to the indigenous small scale farmers at the Manzou Estate . As the journalists drove closer to the mine sites they encountered men, women and boys by the roadside in threadbare clothes carrying the crude tools of their trade including hammers and rock drill bits who looked at them suspiciously when they said they had come to report on the life and work of artisanal miners.

In the face of negative replies the journalists backed away; the fear and anxiety of the miners is perfectly understandable as they are constantly harassed by ZRP and Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) and bribes are often extorted before their tormentors leave, otherwise arrest and fines can follow for illegal mining, or for not having environmental permits.

They quote Shamiso Mtisi, the deputy director of Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (ZELA) who said: “It is not only about the US dollars; climate change is disrupting production in the agriculture sector, thereby pushing more and more people into [artisanal mining] now a source of livelihood in rural areas and some urban areas.”

The official regulators are not the only ones harassing the artisanal miners who are also raided by ‘shurugwis’ the local name for gangsters and thieves who raid the miners to steal any gold they have extracted. Violence and lawlessness is very much part of the lives of artisanal miners and there have been killings as rival gold barons with political connections vie for promising gold sites. These crimes often go unreported as the reporters themselves may be arrested for illegal mining.

The article quotes the Zimbabwe Peace Project’s October 2019 monthly monitoring report, statistics from Kadoma Hospital that show that between August to October 2019, 105 murders occurred in the Kadoma area and also 221 assaults. Another report by Mukasiri Sibanda of ZELA found that the gangs forcibly recruited miners, sometimes under the watch of police officers meant to guard abandoned mines. Rather than being brought to justice, mine-site marauders seem to enjoy political protection.

The journalists spoke to Chokunda Wodala, 50, a woman artisanal miner at the abandoned DSO mine in Mashava. She said: “You cannot put up with the hustling that happens in the mining fields, for women, all forms of violence, robberies and sexual attacks are rampant.”

They interviewed Mike Garwa, 13, a young man whose father died from silicosis acquired at Gath’s asbestos mine and who was mining because he could not afford school fees. He told them: “Most people my age have stopped going to school out of necessity. We are in mining just for subsistence, we get something to eat and to buy clothes.”

The Zimbabwe Miners Federation has adopted the following categories of mining operations

• Class A: Miners which have full mining permits, qualified mining management, standard mining operation and gold production of 5kg per month or more.

• Class B: Mining operations which hire technical expertise, like a geologist, and may hire equipment as needed. Gold production is up to 5kg per month.

• Class C: This category fits the majority of Zimbabwe Artisanal Small Miners. These are mining operations run by people with mining claims who hire labourers to work the site and are usually registered and may use simple mechanised equipment. Mining is often done by syndicates, which have profit-sharing agreements.

• Class D: Artisanal miners, who use rudimentary tools such as pans, picks and shovels and do not have a mining title. Some may have a prospecting licence.

The 1961 Mines and Minerals Act permits any individual to apply for a mining licence provided they are a “permanent resident of Zimbabwe.”

An historical perspective

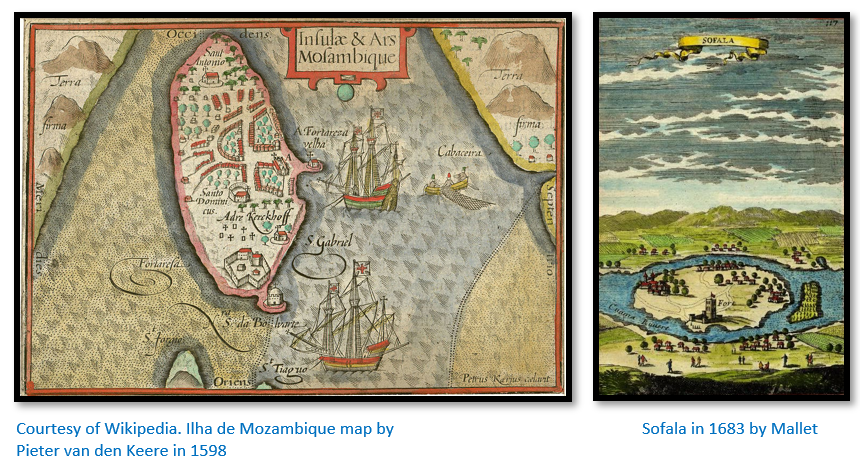

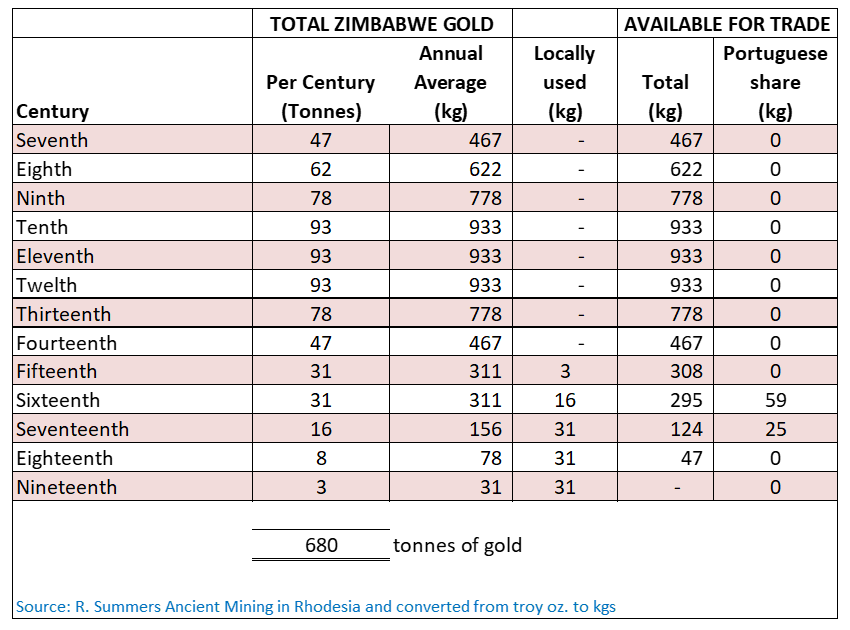

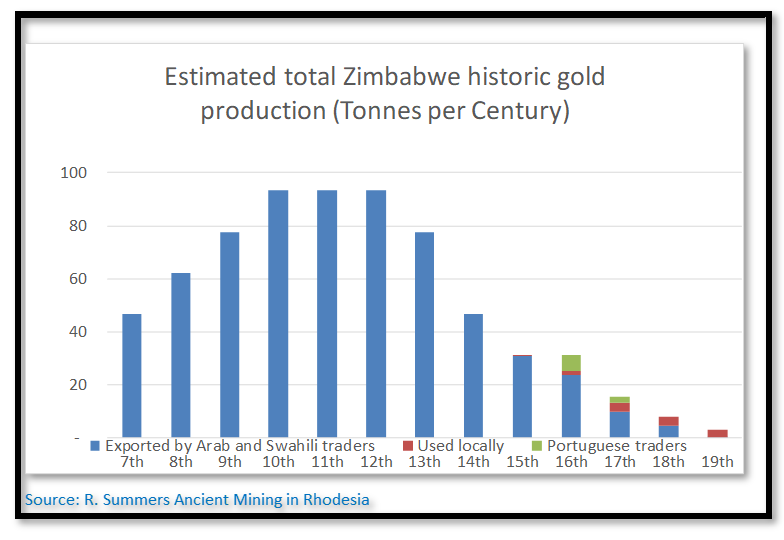

Artisanal gold mining in Zimbabwe dates back to at least the thirteenth century when the Munhumutapa Empire traded with Swahili traders and Kilwa was the principal port in a string of coastal trading cities, including Sofala, Quelimane, Angoche and Mozambique Island that formed along what became known as the Swahili Coast.

Dhows, the sailing ships of East Africa were driven by the monsoon winds from Kilwa across the Indian Ocean to India and China as well as to Arabia and Persia. Gold, grain, tortoise shell, wood and ivory were exported in return for cotton, ceramics, Chinese porcelains and silk.

The island of Kilwa may have been settled as early as the fourth century and by the eighth century a predominately Swahili culture began to take shape which united the African coast from Somalia in the north to present-day Mozambique. A mix of African, Arabian, and Persian cultures resulted in Islam becoming established and Muslim traders taking an active part in the trade. The first mosque on Kilwa has been dated to around A.D. 800.

The dynastic founder of the Kilwa sultanate was according to the Kilwa Chronicle, an 11th-century adventurer Ali ibn al-Hassan Shirazi whose name suggests he originated from Shiraz in Persia. Soon Kilwa rivalled the leading trading centre of Mogadishu in present-day Somalia far to the north and controlled Sofala as its most southerly port from where gold from the interior including present-day Zimbabwe had traditionally been traded

Sofala the seaport of the Munhumutapa Empire

Sofala was connected by the Buzi River to the gold fair (feira) at Manica and from there to the gold fields of Munhumutapa in present-day Zimbabwe. Sofala was a small trading post in the 10th century but grew steadily after being merged in the 1180’s into the Kilwa Sultanate and the Swahili trade network that included river-going dhows up the Buzi and Save rivers to bring the gold from the interior to the coast.

The gold trade enriched the merchants of Sofala and far from being just an outpost of Kilwa the town grew prosperous with trade connections as far south as Cape Correntes and across the channel to Madagascar.

Revenue from the gold trade proved a windfall for the Sultans of Kilwa allowing them to finance the expansion of the Swahili commercial empire all along the East African coast, but also attracted the attentions of the Portuguese. The first European to visit Sofala was the Portuguese explorer and spy Pero da Covilha who travelled overland disguised as an Arab merchant in 1489. His secret report to Lisbon identified Sofala's role in the export of gold although the gold trade by that date was quite diminished from its peak in the tenth to twelfth centuries. In 1501 Sofala was scoutd from the sea and its location determined by The Portuguese captain Sancho de Tovar and in the following year Pedro de Aguiar (others say Vasco da Gama himself) led the first Portuguese ships to Sofala.

The gold trade proved a great disappointment to the Portuguese as the surface and shallow deposits of Manica were largely exhausted and gold production had moved further north onto the Mashona plateau. Feira’s would in time be established at Angwa (Ongoe) Dambarare, Luanze, Masapa (Fura) Maramuca (Rimuka) Piringani (Ditchwe) within present-day Zimbabwe but Sofala was less conveniently positioned as an outlet than the rising towns of Quelimane and Angoche.

The same problems that plagued local pre-European miners during the wet season, the ingress of water into the workings as the water table rises, hampers present-day artisanal miners today as they go deeper and increases their need for pumps and compressors.

Geology of the gold belts

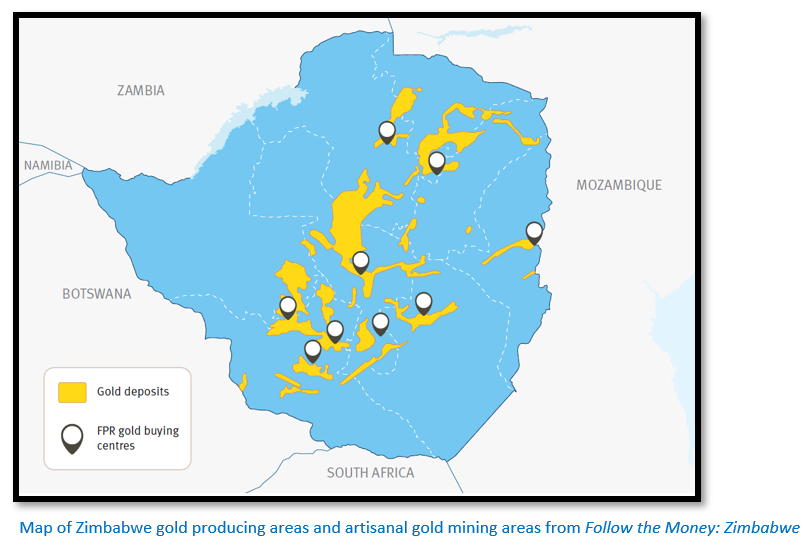

About 69% of Zimbabwe’s surface is composed of granite deposited in an Archaean-age basement usually referred to as the Zimbabwe Craton that enclose sedimentary layers usually found at the margins of the granite called greenstone belts that host the gold usually within quartz. Alluvial gold is found in many of the rivers that flow through the greenstone belts such as the Mazowe and Ruenya rivers.

Pre-European gold mining

Pre-European miners understood the underlying geology and abandoned gold workings were found at Hartley Hills near present-day Chegutu by Henry Hartley in 1866 and confirmed by Karl Mauch a year later who also found gold in the associated quartz reefs. To the early European prospectors after 1890: “the simplest surface indicator to spot was an ancient working, a depression or series of depressions where tree growth was more luxurious than on the surrounding veld.”[vii]

The Mashona were well aware of their significance. Baines gives a description in his Northern Goldfields Diary under Wednesday, 22 September 1869 a description of what one of the old mines looked like:[viii] “It was of serpentine form, nearly filled up and had a young tree of considerable size growing in the accumulated debris, showing that many years must have passed since it was disturbed but not apparently proving for it a very high antiquity…none of the pits, I can hardly call them by the title of mines – appear to have been very recently worked, but several of the old Mashona remember these workings and one of them, seeing Mr Hartley during the journey in which Mauch was with him [i.e. 1867] examining a stone, said to him, ‘I know what you are looking for; it is metal of this colour – pointing to the brass ring on his arm – and not like this – indicating a copper one. He forthwith left the wagon and coming to a hole not far from our last night’s outspan, found and brought back a piece of quartz in which several specks of gold were visible.”

Summers states[ix] “In the nine years between 1890 and the outbreak of the South African War over 100,000 gold claims were pegged, all but a negligible proportion found by following reefs from ancient workings.”

Summers goes onto say[x] “Between 1897 and 1939 nearly all the ancient workings in Rhodesia were cleared out. This was enough to pay the miner and his labourers for their work, but in some cases there was sufficient surplus to pay for development work on a large-scale, but in pursuit of wealth scarcely anybody gave a second thought to what came out of the mine beside profit. Now and then a miner would take the odd iron gad or a few stone hammers into a museum, on one memorable occasion a whole mass of material was so deposited [Macardon Claim, West Nicholson]”

Current (official) gold production in Zimbabwe is 33.2 metric tonnes (2018) to 27.5 metric tonnes in 2019 – the approximate equivalent of what was produced in each of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in Zimbabwe.

Artisanal Mining provides a livelihood to many Zimbabweans today

Estimates of the number of Zimbabweans engaged in artisanal gold mining vary widely. A 2017 UNIDO report by Andrew Mambondiyana[xi] estimated that between 2012 to 2017 over 500,000 Zimbabweans were engaged in artisanal mining; whilst another UNIDO report[xii] estimated two million people were dependent on artisanal mining for their livelihood in the absence of jobs in the formal employment sector.

The stories of artisanal miners being paid in US dollars has tempted many thousands of men, women and children from poor rural families into joining the rush into small-scale and particularly artisanal mining in search of a living.[xiii] Efforts to eradicate or formalise the artisanal mining sector are more likely to result in a greater proportion of gold going into the illicit gold trade.

John Chinonzwa the national treasurer-general for the Zimbabwe Miners Federation an umbrella group for small-scale miners said: “we are the new economy drivers and employment creators, but government often turns a blind eye on this reality, stepping on the new golden goose, us, small-scale miners.”[xiv]

The low risk in artisanal mining compared to other activities

In the absence of any formal employment potential in present-day Zimbabwe gold mining offers the potential of good returns for very little risk. In particular, when compared to the risks of punishment for engaging in wildlife trafficking with a mandatory 9 year jail sentence, or in illegal diamond mining the risks associated with artisanal mining and the accompanying illicit gold trade are minimal. The Gold Trade Act has a provision of a maximum 5-year sentence for illegal possession of gold; however, the “no-questions-asked” recently adopted by the government has relaxed this legal requirement in practice although artisanal mining is not without its hazards as the recent tweet below shows:

Where does the artisanal gold mining take place?

Gold mining mostly takes place in the greenstone belts of Zimbabwe that are found in every province and are shown in yellow below, but alluvial panning takes place in other areas such as the Chimanimani mountains in the south east of the country.

However the majority of artisanal gold mining takes place in the Midlands province around the towns of Kwekwe and Shurugwi (formerly Que Que and Selukwe) and Mashonaland West province at Kadoma (formerly Gatooma) Kwekwe that has the largest gold producer in the Globe and Phoenix mine is known as the ‘Chikorokoza capital’ of Zimbabwe, the term describing informal, unregistered and illegal miners.

Mine-site participants in Zimbabwe’s artisanal gold-mining

These can be divided into the following:

- Artisanal miners themselves

- Mine owners and their managers

- Landowners

The article Follow the Money: Zimbabwe makes the following general observations regarding artisanal miners:

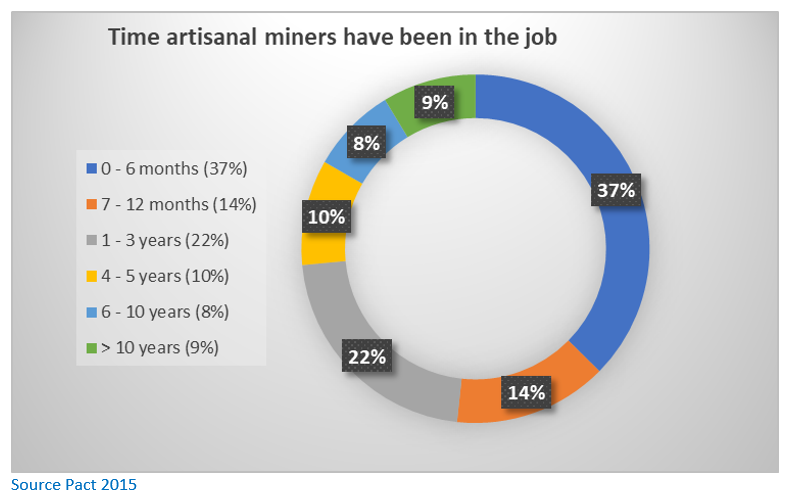

- Many artisanal miners live in local communities around the gold producing areas and take up mining because of limited employment opportunities elsewhere

- Where there are gold rushes individuals from other areas will flock into the mine sites including to a limited degree, foreign nationals

- Mining is dominated by men, but particularly in artisanal mining, women and children are increasingly become engaged in mining activities

The legality of artisanal mining

The legality of Class C (Artisanal Small Miners) and D (Artisanal Miners) varies greatly. Whilst Artisanal Small Miners may operate legally with the required mining permits, there are estimates that as much as 80% of artisanal miners operate informally, unregistered and illegally and are known locally as makorokoza (literally ‘panners’)

They generally operate as syndicates to take out the ore and share the profits after the ore is processed and these syndicates may comprise groups of artisanal miners moving from one gold rush to another, or temporary syndicates of convenience, or they may be organised and permanent.

How are profits shared in a syndicate?

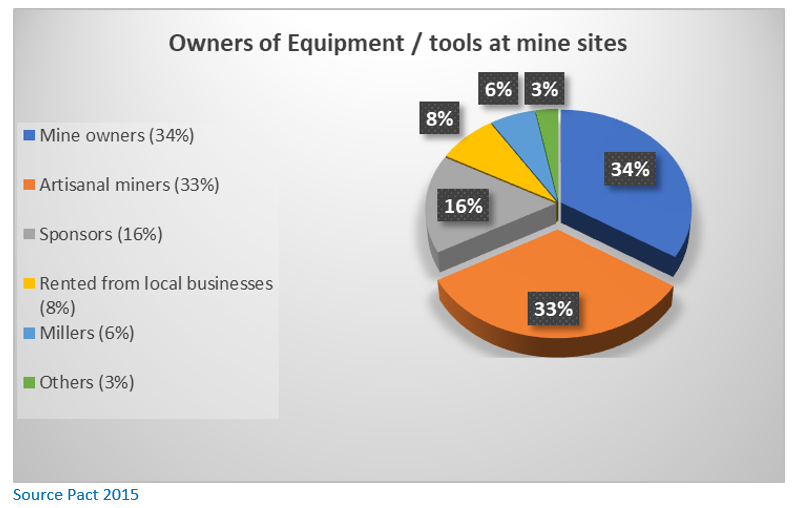

Artisanal miners usually do not receive wages, but rather a share of the profits. The share is dependent upon whether machinery in the form of air compressors, backhoe loader or tractor / trailer, etc. is provided and any other expenses incurred by a sponsor.

Commonly if there is little machinery used, 50% of profits after expenses are shared amongst the artisanal miners with the claim owner / sponsor / landowner receiving an equal share.

However if machinery has to be provided, the artisanal miners may only receive 30% of profits after millers, mine owners and landowners are paid.

Most landowners will require a percentage of the profits for the right to mine on their land as will the claim owner. Estimates of 11% are quoted in the report.

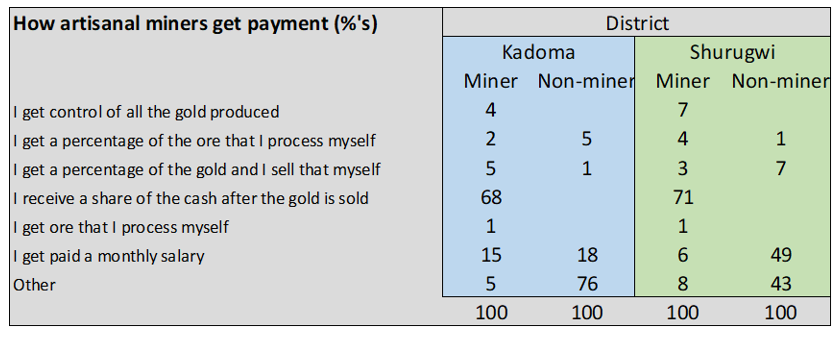

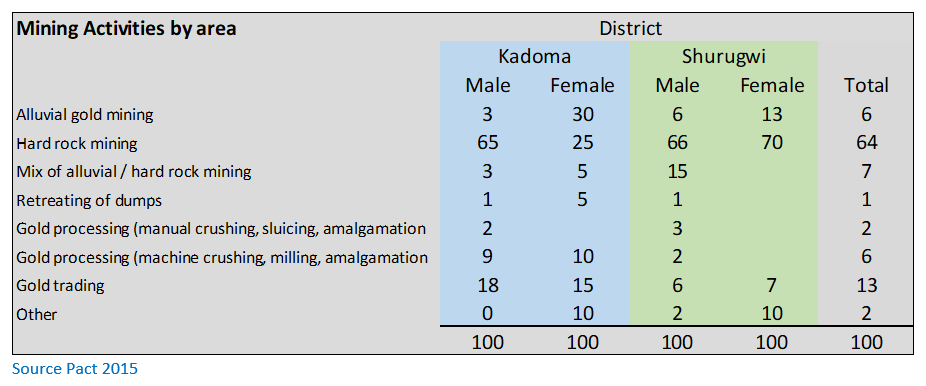

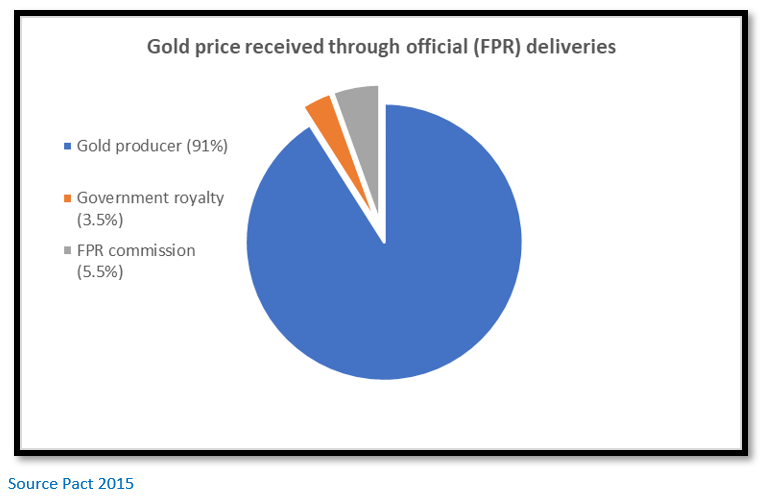

The above information and the tables and graphs are from information contained in Pact: A Golden Opportunity: Scoping Study of Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining in Zimbabwe (2015) that resulted from a questionnaire of miners and non-miners in the Kadoma and Shurugwi districts and demonstrated:

Miners predominately receive a share of the profits after expenses

Non-miners typically did not receive a share of the profit, but might get a monthly cash payment

What form of payments do artisanal miners expect to receive?

They are paid after the ore extracted has been milled when the gold is sold to illicit buyers. The gold itself tends to be sold on quickly as there is a higher risk of holding gold than of holding cash.

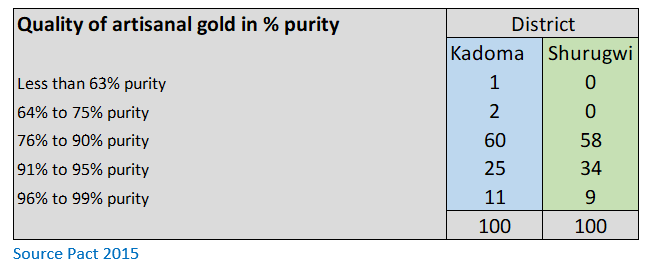

What do artisanal miners get paid for their gold?

The price can vary from 83% to 95% of the value of the gold. The Pact (2015) report found that most gold sales tended to be up to 10 grams with a purity of about 50% i.e. up to $300 (using Sept 2020 price of $60 per gram)

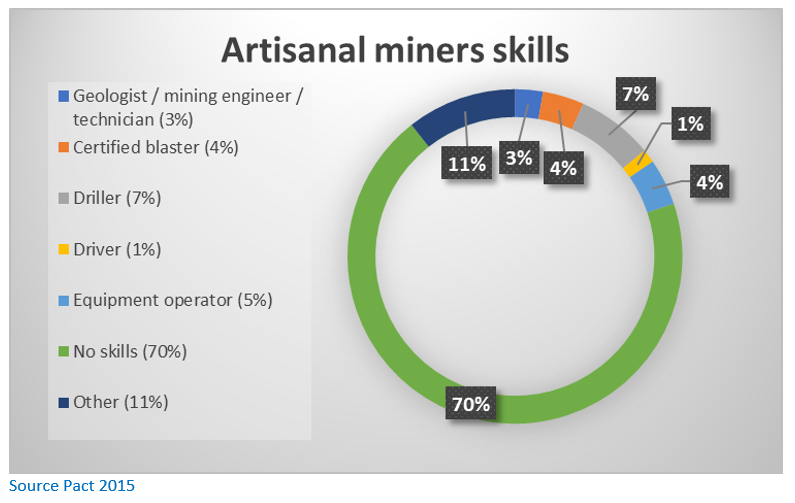

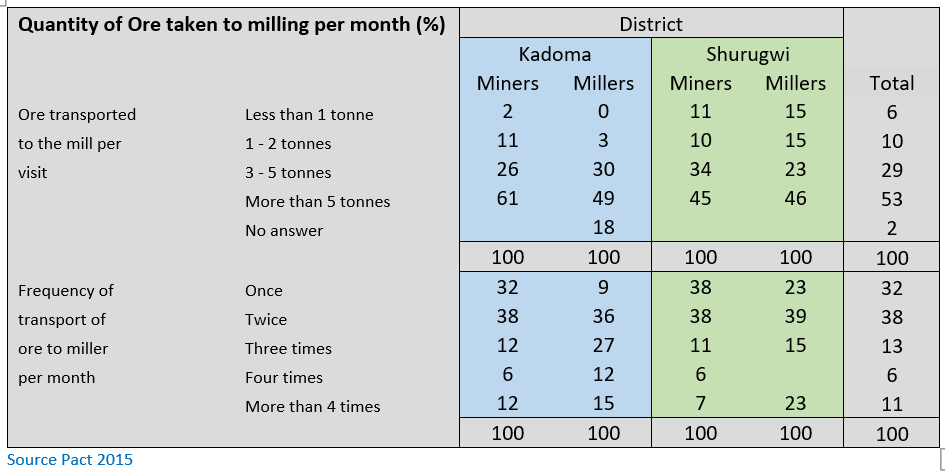

Pact 2015 Data Summary on Artisanal Miners

The Ore Milling process

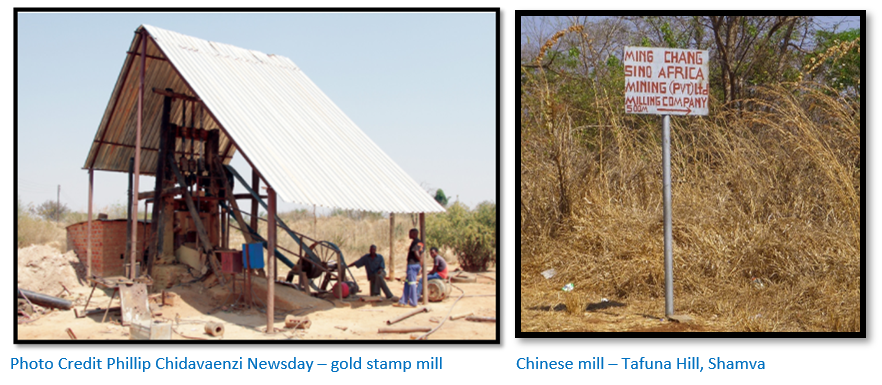

Although this article concentrates on the artisanal miners it is hard to ignore the vital part played by the millers in gold processing in Zimbabwe.

Most gold is found in the quartz bearing rock of the greenstone belts which is extremely hard and needs to be milled to liberate the gold which may be as low as 2 grams per ton. Larger producers will have their own mills, but most small scale and artisanal miners will need to use custom mills who either:

- buy the ore directly from miners

- crush the ore for the miners either by:

- wet stamp mills (3 or 5 stamps) with capacity of 0.2 to 0.5 tonne per hour depending on the hardness of the rock

- use jaw crushers followed by grinding with ball mills with capacity of 0.7 to 2 tonnes per hour again depending on the hardness of the rock.

The millers will charge per hour or per tonne for the grinding and concentration. Stamp mills are mostly used in Zimbabwe – many artisanal miners believe ball mills retain part of the gold in the internal liners and distrust them. The ore bearing rock is crushed into a fine powder to liberate the gold which is then discharged through a 0.6 to 0.8 mm screen into a locally made centrifuge or onto copper amalgam plates where the gold is adsorbed by mercury.

Where a centrifuge is used the concentrate is generally given back to the miners who use amalgamation barrels usually provided free by the millers. The miners add their own mix of soap, acids, mercury or sodium cyanide tablets and the material obtained from the amalgamation barrels is concentrated by panning in a plastic bowl.

The tailings from the stamp mill are sometimes reground with added mercury in the miners homes and roasted in their kitchen.

Do millers treat artisanal miners fairly?

A good question. Much of the gold is left in the primary tailings and the millers apply vat-cyanidation to extract this remaining gold for their own benefit and from which the artisanal miners receive no value. Most millers have cyanidation tanks which can each hold from 20 to 70 tonnes of tailings to which is added sodium cyanide to extract the residual gold.

This residual gold in the tailings is a major source of conflict between artisanal miners and millers as the miller can adjust the settings on the stamp mill so that the milling residue is coarse and less free mill gold is released. It is estimated that up to 50% of the gold is recovered in the milling process for the benefit of the artisanal miner leaving the remainder in the tailings for the miller.

The millers appear to get many bites of the cherry:

- They charge for the milling

- They may charge a fixed amount for cleaning the screen box

- They may charge for mercury

- They may not pass on government royalties[xv] and taxes and

- They keep all of the gold obtained from the tailings

- Millers are also automatically agents for Fidelity Printing and Refining (FPR) where all legally obtained gold must be sold and will pay from $0.5 to $1.5 per gram less than the daily gold price.

Milling is both a weak and important link in the gold supply chain.

Pact 2015 Data Summary on Millers

Illegal gold

There are a number of vulnerabilities in the gold supply chain.

Many artisanal miners do their own milling using hammers to break the ore or have their own ball mills which enables them to sell gold directly to illicit buyers thus avoiding government royalties and taxes.

Millers may sell directly to illicit buyers rather than FPR, thus avoiding government royalties and taxes and are thus able to offer artisanal miners a higher price to use their mills.

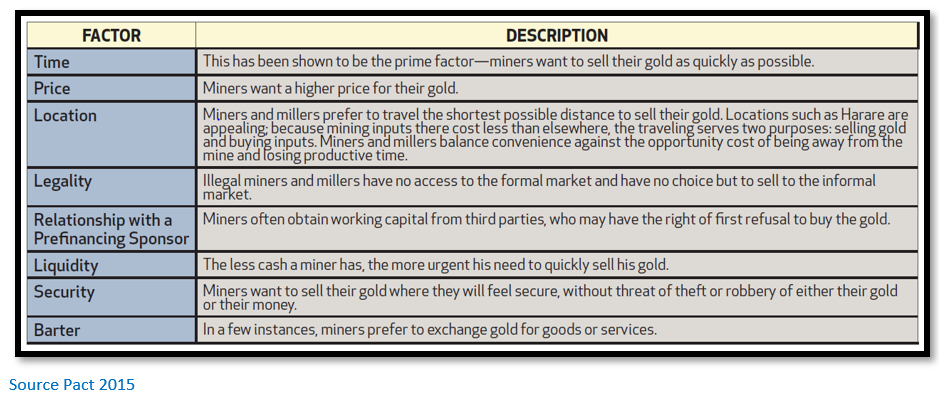

The Follow the Money: Zimbabwe report concludes that some of the drivers of the illicit artisanal gold trade are:

- Higher prices paid for illicit gold than by FRP

- Greater portion paid in USD cash rather than government bond notes

- Ease of business with runners going to the mine sites

- Gold barons will often pre-finance gold mining activities as there is a lack of access to formal financing by artisanal miners

Buyers

- Licensed official gold buyers (including millers) sell direct to FPR and they may divert some of their purchases to the illicit trade

- Individual illicit gold buyers who may be licensed miners buying from artisanal miners

- Illicit gold barons

- Illicit foreign buyers including Zimbabwe diaspora working independently or with local partners to smuggle gold out of Zimbabwe primarily to South Africa. Chinese nationals often operate as millers and become part of the gold supply chain.

- Foreign diplomats attached to local foreign embassies and consulates[xvi]

Licensed official gold buyers can employ up to five agents working for them and will often employ family or friends because of the high levels of trust required. The licensed official gold buyer will quote a per gram gold price and the agent will keep the difference between that price and the price they can negotiate with artisanal miners.

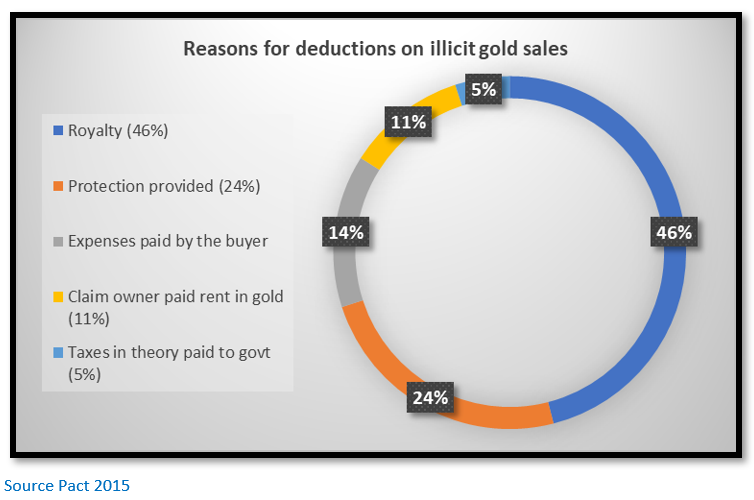

Illicit gold buyers are thought to make the highest profits in the gold supply chain and there are many anecdotal stories about their luxury lifestyles. The Pact 2015 report revealed that many small-scale registered miners were buying gold from unlicensed artisanal miners.

Gold barons and their agents known as runners are thought to be the largest buyers of illicit gold in Zimbabwe. They are mainly based in Harare and they buy from their runners who are quasi-employed by them on a semi-permanent basis and also from independent informal traders. One agent interviewed in the Pact 2015 report revealed he would get an initial float of $10,000 from the gold baron. On a good day he would get 200 grams of gold and perhaps 4 to 5 kg per month. The gold baron would pay him transport costs and $0.5 per gram of gold.

Foreign nationals (mainly Chinese) and Zimbabwean diaspora in South Africa also buy gold illicitly from small-scale and artisanal miners.

It is reported that many licensed buyers sell some of their gold to FPR thus keeping to the legal supply chain in order to avoid getting into trouble with the legal authorities and sell the rest of their gold on the black market where they get a better profit margin.

Gold prices paid to artisanal miners

The local gold price is based upon the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) daily gold spot price. Licensed official buyers are not supposed to pay less than 2.5% off the LBMA price. Illicit gold buyers will compare the FPR price with the LBMA price but also need to account for the purity of the gold product, so that the discount they offer may range from $1 to $6 per gram. The PACT 2015 report quoted sources saying that the gold barons were trying to squeeze smaller gold buyers out of the market by taking advantage of economies of scale to offer higher prices and by only taking $0.5 off the LBMA price.

The role paid by Fidelity Printing and Refining (FPR)

Official gold buyer – by law the RBZ is the only buyer and exporter of gold in Zimbabwe. The FRP acts as the RBZ’s gold-buying agency with a monopoly to buy, refine and sell the gold to South Africa’s Rand Refinery which is Africa’s only refiner accredited with the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA)

Prices - The FPR has had a policy of paying for gold partially in cash with the balance in government bond notes with the cash amount varying from 50 to 70%. Artisanal miners want to be paid in cash as many do not have bank accounts, but often the FPR struggles to find cash and the lack of it may push the artisanal miners to sell to illicit buyers who can pay in cash.

The journalists Stephen Tsoroti and Ankita Anand[xvii] were told by Henrietta Rushwaya, president of the Zimbabwe Miners Federation, a grouping of artisanal and small scale miners, that for every gram of gold sold to the RBZ, it pays 55 percent of the cost in Zimbabwean dollars and 45 percent in US dollars. “However, if an agent buys directly from the miner, they pay 100 percent of the price in USD. The artisanal miners then get a better price than they would have got from RBZ, which they can’t approach in any case as they don’t have the licence or permit to mine.”

FPR buys all gold on a ‘no questions asked’ policy and does not discourage agents from buying from artisanal miners in order to combat the illicit gold trade. This may contribute to capturing more of the artisanal gold output, but the Pact 2015 report found: “Almost half of miners were unaware of the FPR price for gold, but only 35 percent were unaware of the informal price for gold—suggesting that miners engage more often with informal traders than in the formal system. That said, 65 percent of miners asserted that they sold their gold on the formal market (i.e. to FPR and millers), nearly twice the 35 percent who admitted to selling on the informal market (i.e. to traders, claim owners and sponsors) Thus it can be estimated that between 35 and 50 percent of miners sell their gold on the formal market, with 130 kilograms (about 287 lbs) going to FPR each month. By extension, an estimated 130 to 240 kilograms (about 529 lbs) of gold reaches the informal sector each month.”

The role of the Ministry of Mines and Mining Development (MMMD)

The MMMD is the ministry responsible for mines and mining in Zimbabwe. The MMMD oversees the Zimbabwe Geological Survey and the Zimbabwe Government Mining Engineer and in regulating the mining sector, the MMMD works closely with the ZRP, in particular the minerals and border control unit in relation to smuggling. When an illegal mine is located, due to safety concerns, the ZRP minerals and border control unit are notified. The MMMD also works with the FPR and this includes monitoring the activities of gold buyers to ensure their records match the FPR’s records.

The Follow the Money: Zimbabwe report additionally notes that the MMMD’s resources are severely constricted to both regulate and assist the sector with only two vehicles shared by five departments which significantly restricts the MMMD’s ability to visit mine sites.

The enforcers - Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP)

The ZRP’s priorities are enforcing the 1961 Mines and Minerals Act together with the MMMD and combatting the illicit gold trade. Their enforcement actions include checking mining permits and taking action when other authorities (such as the MMMD, the FPR, traditional authorities or others) report illegal mining to the ZRP.

The ZRP is reported to be very active in the artisanal mining sector, particularly agents from the Minerals and Border Control Unit (MBCU) and the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). In most cases ZRP has been accused of non-stop visits to miners knowing that it is virtually impossible for them to be compliant and this has led to strong allegations of harassment and a bribery culture.

The rise in artisanal and small-scale mining (ASGM)

As can be seen below in the graph in 2017 the supply of gold to FPR from ASGM’s exceeded that of the large-scale producers (LSP’s) for the first time and in 2018 was nearly double that of LSP’s with gold deliveries of 21.7 versus 11.5 tonnes. FPR, the Zimbabwe government’s official buyer is now purchasing 1.8 tonnes of gold a month from AGSM’s.

There is a strong correlation between the current upwards trend in gold prices and the growing proportion of gold deliveries to FPR coming from small-scale and artisanal miners as the above graph demonstrates. In 2015 they contributed 37% of total gold deliveries which had risen to 65% in 2018.

The 2019 decline in gold production is attributed by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) to power shortages, a lack of mining equipment and leakages from the gold supply chain to the illicit gold trade. To some extent the rise in gold prices has served to mitigate the decline in production. [See LBMA gold price chart above] Some economists also attribute delays in payments for gold deliveries by FPR as another factor mitigating gold delivery via the legal route as illicit buyers pay immediately in cash.[xviii]

If we assume that 50% of gold production is lost to smuggling (as suggested in the paragraph below) then ASGM’s are producing 3.6 tonnes of gold a month which is worth $60 per gram at current prices [Sept 2020] then annual ASGM gold production would be worth (43,000 kgs x $60,000 per kg = $2.58 billion dollars)

Illicit gold trade

Some of the factors and players in the black market have already been highlighted. The PACT 2015 report stated: “while official production figures have been growing, it is widely thought most output from ASGM is unaccounted for, rendering official output figures a massive underestimation.” The report goes on to state that: “a common estimate is that 50% of ASGM gold production is lost to smuggling.”

Table showing why artisanal miners sell to informal buyers rather than the FPR

Illicit gold buyers often provide the financial assistance that artisanal miners require as there is a lack of access to formal financing. They also provide political protection from outside groups and the law enforcement agents such as Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) and the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) both of whom often become players if there is a significant source of revenue.

The Pact 2015 study revealed that 52% of artisanal miners said deductions were made when they sold their gold to illicit buyers (48% had no deductions made) These deductions might be for milling and transport, food and operational costs including protection and royalties for the gold claim rights.

The legal status of artisanal miners has shifted

The report Follow the Money: Zimbabwe concludes that Zimbabwe’s legislation currently does not differentiate between artisanal and small-scale and gold mining (ASGM) and large-scale mining (LSM) and it is difficult for ASGM’s to comply with the legislation and operate legally. They are often long distances from licensing offices and the lengthy processing times and high costs are a deterrent to obtaining licences for each link in the gold supply chain (i.e. mining, milling and buying)

Artisanal mining is frequently the only economic opportunity available to local communities in Zimbabwe with the existing economic crisis and lack of formal job opportunities. The resulting cash inflows from gold mining are extremely positive for those communities and gives the artisanal miners a sense of legitimacy in that they may be the only external cash contributors for local people.

In public perception artisanal mining is believed to consist of unregistered or unlicensed mining using pans, picks and shovels, whilst small-scale mining tends to be registered and is more organised with some machinery such as compressors, pumps and rock drills.

The report ‘Shifting Formalization Policies and Recentralizing Power: The Case of Zimbabwe’s Artisanal Gold Mining Sector’ by Samuel J. Spiegel provides a good overview of the government’s relationship with artisanal mining.

In the 1990’s to early 2000’s the government provided incentives and rewards for ASGM’s by providing stable gold prices – at times higher than the LBMA gold price and favourable legislation. The 1993 Harare Guidelines promoted the legalisation of artisanal mining recognising that it created jobs and was wealth creating.

Statutory Instrument 275 (1991) Regulations on Alluvial Gold Panning in Public Streams created a structure which allowed Rural District Councils (RDCs) to issue licences to riverbed gold panners independently of the Ministry of Mines and Mining Development and was responsible for training centres which also served as gold buying centres for panners.

But the scheme failed to work due to lack of technical support and the low fees of 0.001% received by RDCs. Various other schemes including Shamva gold processing mill which it was hoped would provide an incentive for artisanal miners to become licenced as only registered miners could use the mill failed and were abandoned as did the Mining Investment Loan (MIL) Fund which was crippled by hyper-inflation and accusations of corruption and election motivated distribution of funds.

Things then changed by 2006 when Zimbabwe’s economic crisis after the farm invasions created an environment which made artisanal mining very attractive to the nations’ jobless youth and mining became about the only sector to thrive, but with low prices offered by FPR almost all of the gold production was sold on the “parallel” or black market.

Government had made previous attempts to clamp down on artisanal mining in 2003 when the army cracked down with Operation ‘Mariyawanda’ “too much money.” In 2006 Operation ‘Chikorokoza Chapera’ “no more illegal mining” was announced which criminalised artisanal mining and repealed S.I. 275 (1991) removing all control from RDCs. Over 16,000 people were arrested.[xx]

Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) crackdowns throughout the country led to hundreds of artisanal miners being arrested and their gold confiscated with imprisonment terms of up to five years for illegal possession. However many of the gold barons had strong political connections and to the ZRP which led to very uneven enforcement as the corruption permeated to the very highest levels of ZANU-PF and government.

The alleged justification for the crackdown was environmental damage and all gold miners – licensed and unlicensed were required to submit Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports.

Zimbabwe’s regulation now recognises the reality

From January 2014 artisanal mining activities were decriminalised and the miners are no longer being harassed by law enforcement. However the report Follow the Money: Zimbabwe finds that the complicated and outdated legislation holds development of the mining industry back.

PACT 2015 states “Zimbabwe’s legal and policy framework for mining is generally burdensome, with more than 40 acts of parliament regulating mining operations. Artisanal mining is directly affected by 24 of these acts and by the statutory instruments that fall under them.”[xxi] The report continues: “The Mines and Minerals Act is old and it has become difficult to marry it with policies meant to stimulate growth within the mining industry and advance the nation socioeconomically.”

The mining regulators

Complicated legislation through the Mines and Minerals Act (MMA) and the Gold Trade Act along with other related legislation have led to many regulators of artisanal mining. The dominant regulators are Ministry of Mines and Mining Development (MMMD) the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) via Fidelity Printers and Refiners (FPR) and the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) Other regulators include Environmental Management Agency (EMA) Rural District Councils (RDCs) National Social Security Authority (NSSA) Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA) and even traditional community leaders. All these various regulators lead to overlap and a high degree of confusion.

The Follow the Money: Zimbabwe report concluded that the use of violence, corruption and politics by the regulators, particularly ZRP and ZNA plays an important role in the artisanal mining sector.

One of the key findings of the Follow the Money: Zimbabwe report was that attempts to eradicate the artisanal mining sector, rather than formalise it, are likely to result in greater illicit market activity.

What about gold panning?

Gold panning is widespread throughout Zimbabwe as local communities work in streams and rivers and sometimes panning the tailings from former gold mining operations. In the dry season they divert the river and excavate the gravels to concentrate gold in improvised sluice boxes. Typically they process from 1.5 to 2 tonnes of material per day to recover from 0.2 to 0.4 gram of gold ($12 to $25 per day at current gold prices) and up to 12 grams of mercury per month.

Panners are usually working in remote areas and are from local communities and neighbouring countries and subject to harassment from Zimbabwe Republic Police.

Woman in artisanal mining

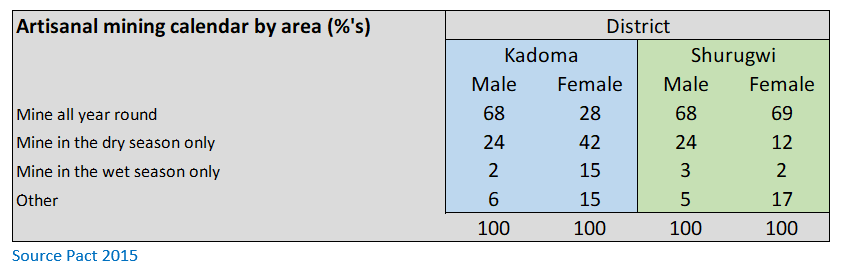

The Pact 2015 study showed that artisanal mining provides an important opportunity for women to find employment outside agriculture and that women frequently turn to artisanal mining in the dry season to supplement their family income. They often are less visible around mines and their numbers may be higher than the 50% that is generally quoted for Zimbabwe.

At the mining sites women engage in digging (although few engage in blasting, hoisting and drilling) crushing and pounding rocks, washing and sorting ore material, carry out processing such as gold amalgamation and transporting material to the mills. Women also provide services to mining areas, including preparing food, selling goods and sex work.

The study found that typically women work in less mechanized artisanal mining operations and as the mechanization increases, so the number of women involved drops.

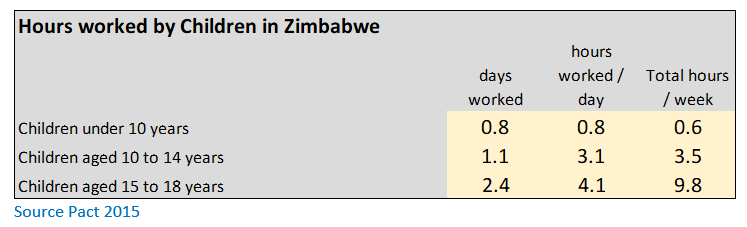

Children in artisanal mining

The Pact 2015 study noted that children are often first introduced to the mining when they accompany a parent to work. Their labour might start out initially as a side activity but grows in significance with age and over time the family may come to rely on the extra income generated for household expenses or school fees.

Under international and domestic laws the Zimbabwean government is obliged to protect children’s

rights, including labour and sexual exploitation.

In the study only 5% of Zimbabwean artisanal miners reported being assisted by children. But conditions vary across the African continent. In the DRC children often engage in lighter surface digging or in the transport, sorting or washing of minerals and the selling of goods to fellow workers, as they enter adolescence they take on progressively more adult roles. In Tanzania, children are involved in every phase of the mining process in small-scale gold mines. They dig and drill in deep, unstable pits during shifts of up to 24 hours. They transport heavy bags of waste material and gold ore and are involved in manually crushing the ore and the subsequent amalgamation.

The Pact 2015 study itself acknowledges that the above figures seem low when compared with UNICEF and other international studies.

The study makes the point that children are particularly vulnerable to exposure to dust and chemicals including mercury because their bodies are still developing and girls working around mine sites are at risk of sexual harassment, including pressure to engage in sex work and are particularly vulnerable to early sexual debut or pregnancy.

Women miners reported that children would start panning because they had seen other children of their age making money from it, creating peer pressure for non-working children to start earning their own money. Children as young as Grade 5 were reported to be familiar with gold panning.

Livelihoods

The Pact 2015 study found that miners saved more money (US$60.28 per month) than non-miners, such as farmers (US$32.51 per month) probably because they earn more. In 2006 the Global Mercury Project (GMP) conducted a baseline survey in Kadoma-Chakari district that revealed that miners’ wages were much greater than farmers’ wages - often five times as high and this corroborates Pact 2015 findings that show miners spend more on their families and still save twice as much as non-miners.

Artisanal miners and the use of mercury

One of the greatest criticisms of artisanal miners is their use of mercury. Mercury is used to recover any gold mixed in concentrates as the gold combines with the mercury to form an amalgam. In Zimbabwe artisanal miners do not use retorts to vaporise the mercury as wood fires are fairly low temperature and they claim the process is too time consuming. The mercury / gold amalgam is put in a tin directly into a wood fire without protection, but at these low temperatures the retorting process is very incomplete and the resulting doré gold often has 20% of residual mercury.

More than 1,400 tons of mercury per year are released into the environment from over 70 countries and the largest source is artisanal gold mining.[xxii] Mercury is widely used by Zimbabwe’s artisanal miners with those involved having little knowledge of the dangers of the chemical or of alternative processing methods. Pact 2015 reported that only 46% of miners knew about the health problems related to mercury but 23% of respondents had experienced headaches, dizziness and blurred vision, 12% had experienced skin irritation and sores and nearly 26% reported muscle pain and weakness, all symptoms of mercury poisoning.

Miners and panners often divert the course of streams with their digging and they dump mercury and cyanide into the water making them harmful to others downstream. Government programs are training artisanal miners about the benefits of working in an environmentally friendly manner.

Solutions to the problem of the illicit gold supply chain

Former Zimbabwean Finance Minister Tendai Biti believes the problem will only be halted when:

- The Zimbabwean government gets a grip on corruption which currently permeates to the very top of the pyramid

- Ends the arbitrary mining and title administration system

- Manages to stop the mine site marauders ‘shurugwis’

- Legalizes artisanal miners’ activities by granting them special permits.

Until well-considered policy interventions are implemented that formalize small-scale and artisanal mining operations and stimulate gold deliveries through official channels and also protect vulnerable populations, the environment and sustainable mining practices, hundreds of thousands of artisanal miners in Zimbabwe will continue to have to risk their lives in order to make a living.

References

K. Chimhangwa. Zimbabwe’s new gold rush. www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/zimbabwes-new-gold-rush/ 7 August 2020

S. Tsoroti and A. Anand. Small scale miners risk life and limb in Zimbabwe. www.towardfreedom.org/story/small-scale-miners-risk-life-and-limb-in-zimbabwe/ 21 August 2020

M. Jose Noai. This abandoned East African city once controlled the medieval gold trade. National Geographic. 7 September 2020.

M. Hunter. Follow the Money: Zimbabwe. United Nations Industrial Development Organization and The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. March 2018 www.unido.org/Zimbabwe ASGM_28.04.18

PACT: A Golden Opportunity: Scoping Study of Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining in Zimbabwe, 2015, http://www.pactworld.org/library/golden-opportunity-artisanal-and-small-..., p.

S.J. Spiegel. Shifting Formalization Policies and Recentralizing Power: The Case of Zimbabwe’s Artisanal Gold Mining Sector. Society and Natural Resources Volume 28, 2015

R. Summers. Ancient Mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia, 1969

A. Andoh-Korsah. BBC News. Over 16,000 arrested in Zimbabwe for illegal mining. BBC News 29 December 2006

E. Chenjerai. Zimbabwe’s small-scale, Artisanal Miners Emerge as Country’s Biggest Gold Producers. Global Press Journal 26 February 2017

Notes

[ii] Zimbabwe's new gold rush

[iii] Zimbabwe’s new gold rush article

[v] Worldpopulationreview.com/countries/Zimbabwe

[vi] BBC News – Reality check: Are 90% 0f Zimbabweans unemployed? https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-42116932

[vii] Ancient Mining in Rhodesia, P4

[viii] Ibid, P3

[ix] Ancient Mining in Rhodesia, P4

[x] Ibid, P6

[xi] Andrew Mambondiyani, Gold fever leaves trail of destruction in Zimbabwe, IOL, 17 April 2017, https://www.iol.co.za/news/special-features/zimbabwe/gold-fever-leaves-t...

[xii] UNIDO: Empowering Small-Scale Miners in Zimbabwe: An Overview of Recommendations from the Global Mercury Project, 2007.

[xiii] Zimbabwe's new gold rush

[xiv]Zimbabwe’s small-scale, Artisanal Miners Emerge as Country’s Biggest Gold Producers

[xv] A 1% is royalty fee applies to small-scale producers selling less than 0.5kg of gold per month and a 3.5% to 5% royalty fee applies to larger producers.

[xvi] Small scale miners risk life and limb in Zimbabwe

[xvii] Ibid

[xviii] Zimbabwe's new gold rush

[xix] ASGM = Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining

[xx] Over 16,000 arrested in Zimbabwe for illegal mining

[xxi] PACT 2015 Page xix

[xxii] Global Environment Facility. Making mercury history in the artisanal & small-scale gold mining sector. 28 September 2017