Zimbabwe’s artisanal gold miners risk being poisoned with mercury (Hg)

Gold is integral to Zimbabwe’s economy

Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM)[i] currently employs more than 1 million[ii] of Zimbabwe’s roughly 15.4 million population[iii] and may support up to three million dependents.[iv] As the price of gold increases, so the number of artisanal miners are drawn into the activity. The high unemployment[v] began when president Robert Mugabe instigated and led the chaotic and violent land-grab in 2000 of white commercial farms and distributed those farms to his senior ZANU-PF party officials and others in the state security sector. Zimbabweans have experienced increasing impoverishment ever since with high unemployment and minimal employment opportunities exacerbated by successive droughts negatively impacting subsistence farming.

A large young population with few employment prospects in and near mineral rich areas like Mazowe in Mashonaland Central) and Makonde district in Mashonaland West turn to artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) in the hopes of earning a living for themselves and their families, others are tempted from places further away by the get-rich stories they hear.

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: a small ASGM milling operation with ball mill

Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) in Zimbabwe

Artisanal and small-scale mining is an important activity in Zimbabwe as for many it provides the only possible source of income, particularly as the formal job sector has almost collapsed completely. The working methods applied in ASGM operations are very different from those used by a conventional mining companies. Typical artisanal miners are males aged 16 to mid-30’s, although the numbers of women and children are increasing, works on instinct, in order to feed his / her family, there is no prior geological exploration, no drilling, no proven reserves, no estimates of ore tonnage output, or engineering studies. The goal of survival is their driving force, while others seek to supplement their subsistence farming activities.

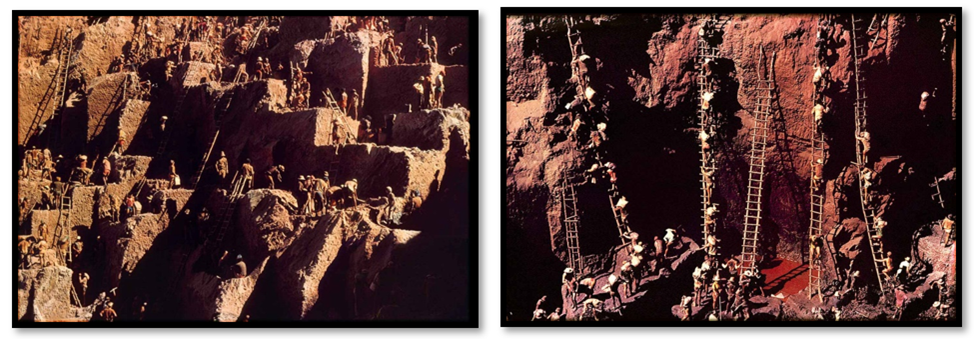

However, don’t confuse artisanal with small-scale! At Serra Pelada, an artisanal mining site in the Brazilian Amazon, up to 100,000 miners or garimpeiros extracted around 90 tonnes of gold in the 1980’s from a single open pit. They took the soil from the bottom of the open pit, filled it into sacks each weighing between 30 - 60 kilograms (65 - 130 lbs) and then carried the heavy sacks up some 150 metres of wood and rope ladders to the top of the mine, where it was sifted for gold using mercury. What started as a hill became a giant open pit, today it’s flooded and dangerously contaminated with mercury.

Photo credit Sebastião Salgado: Serra Pelada known for appalling conditions and violence

Nyavaya and Mushauri write that in Zimbabwean mining terms, there is no separation between artisanal and small-scale mining, although there is a slight distinction between when it is done formally and informally. Although it carries various meanings, ASM is loosely defined as “an activity that encompasses small, medium, informal, legal and illegal miners who use rudimentary methods and processes to extract mineral resources.”

They say estimating the number of ASGM mining sites is impossible, the Ministry of Mines estimates there are four thousand gold deposits in the country.[vi] The Zimbabwe Miners Federation, whose president is the notorious gold smuggler, Henrietta Rushwaya,[vii] states there are about 50,000 registered small-scale miners in the country who employ at least 10 workers each on average.[viii] However with a failing economy and the price of gold currently at US$2,032[ix] the numbers employed in ASGM could have risen to around 1.5 million.[x]

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: Artisanal and small-scale miners

The Mines and Minerals Act (MMA)6 (drafted in 1961 and enacted in 1965) and the Gold Trade Act (1940) mainly govern the gold sector of Zimbabwe. ASGM, which refers to operations conducted by individuals, or small groups as opposed to larger companies, is permitted in Zimbabwe, unlike a number of other countries.

Gold is vital to Zimbabwe’s economy, official figures from the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe state the country sold US$2.14 billion worth of gold in 2020, ranking it 35th amongst world gold exporters.[xi] This figure vastly understates the true figure as much gold it smuggled out the country to South Africa and Dubai.

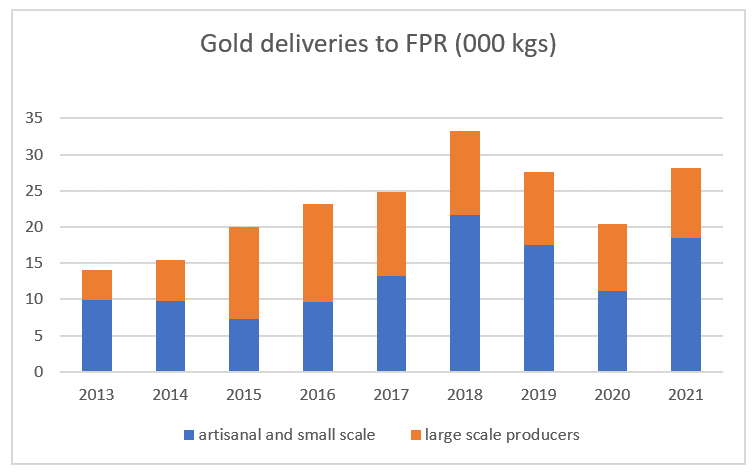

Source Zimbabwe Reserve Bank Annual Reports: These are official figures and do not include smuggled gold

ASGM gold output has increased significantly according to Fidelity Printers and Refiners (FPR), a subsidiary of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe and sole legal buyer of the precious metal and was nearly double the output of large scale producers in 2021. ASGM currently deliver more than 60% of the country’s gold, up from 43% in 2016.[xii] This excludes gold smuggled out the country to South Africa and Dubai that does not reach FDR.

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: ASM hoisting ore

In theory ASM’s need a mining licence, but in practice most do not have one

The Mines and Mineral Act permits any individual, provided they are a “permanent resident of Zimbabwe,” to apply for a mining license. However, for most artisanal miners obtaining a mining license is beyond their reach. A prospecting license costs US$100, pegging a claim by a prospector costs between US$200 and US$300. There are multitudes of official bodies who regulate the mining sector and they all charge. They include the Ministry of Mines and Mining Development (MMMD) Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) Environmental Management Agency (EMA) Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA) and local government authorities. If the ASM does not have the requisite licences, these bodies will all accept bribes to turn a blind eye to their activities and extortion of bribes is commonplace in the gold mining industry.

Nyavaya and Mushauri found that most ASGM operations in Zimbabwe are unregistered, they do not have licences, and thereby operate informally. This state of affairs suits both the artisanal miners and the gold dealers as much of the gold is sold illegally on the black market.

The current strategy of most of the authorities energy is directed towards extorting fines or bribes from ASGM or arresting them, this fuels corruption and contributes to a constant cat and mouse activity that has little benefit to the economy as a whole.

Protection rackets are the norm

ASGM is a significant contributor to the Zimbabwe economy as their gold output outstrips that of the large producers and is therefore tolerated but leads to widespread criminalisation of their operations. In another article I have written “in Zimbabwe the political elite have access through the ZANU-PF government infrastructure securing land access and mining licences, often through corruption or by force. This is facilitated through mismanagement within the relevant mining ministries and artisanal and small workers have little ability to legalise their mining claims. In Zimbabwe mining disputes occur when multiple mining titles are being granted for the same location, which has led to conflict and chaos. Where political actors do not obtain a mining licence, they take over mining operations using deception, political pressure and violence.”[xiii]

In recent years Zimbabwe has experienced a dramatic increase in machete gang violence across ASGM areas. The gangs, popularly known as ‘MaShurugwi’ terrorize mining communities – robbing people of cash, gold and ore. At one time there was hardly a day that passed without a story in the media of MaShurugwi having robbed miners or businesses. The extremely violent nature of the robberies and lack of police intervention especially in the earlier period led to many claims being made in the media about who the violent gangs were and their relationship with politicians in Zimbabwe's ruling ZANU PF political party.

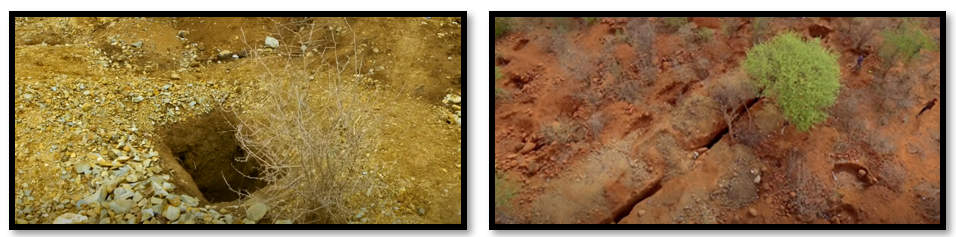

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: typical ASGM shaft and abandoned mining site

In response the police launch periodic crackdowns - “Chikorokoza ngachipere” (putting an end to illegal gold panning) resulted in the arrest of thousands of ASM’s under the guise of removing machete-wielding gangs from mining areas like Mazowe. However, the miners insist that they are targeted wrongfully as they are not gang members and that the known gang lords are spared because of their political influence. In the end, miners pay bribes to the ZRP enforcers who run these periodic crackdowns or run away from state agents to avoid arrest whenever there is an operation. Those close to the politically connected gang lords just pay a “protection fee” so they are able to continue operating.

In their article Nyavaya and Mushauri state that at Jumbo Mine, miners only get access once they have paid an illegal fee to ZRP and other security personnel as a bribe to gain access to the underground levels.

A typical ASGM operation

Except in scale and type of operations most mining operations feature the following steps:

(i) The first stage is prospecting for a likely strike

(ii) Extraction of gold-bearing ore

(iii) Manual crushing – larger operations may have a jaw crusher

(iv) Grinding of ore – either a stamp mill or ball mill

(v) Gravity concentration (sluicing)

(vi) Mercury amalgamation

(vii) Burning of the amalgam

(viii) Processing of the tailings (cyanidation)

(ix) Trading the gold

The economic structure of artisanal miners is little different from any other economic activity with a goal of maximum profit with minimum investment. This inevitably creates a hierarchical organization, with rules and responsibilities for all members. There is always a boss who is the main investor, who hires employees or shares part of the gold production with the workers. In Zimbabwe, the boss is inevitably intertwined with the ruling party ZANU-PF.

Nyavaya and Mushauri state that a typical shaft operation in Mazowe’s Jumbo mine area has five people working on it, four (known as Magweja or Makorokoza ‘those who enter the shafts illegally’) will be carrying out the labour including: digging, blasting, carrying the quartz, etc. while another, called the “sponsor” provides the picks, shovels, ropes and buckets, that he owns or hires, buys the dynamite, fuel for pumping equipment and mercury, food and water.

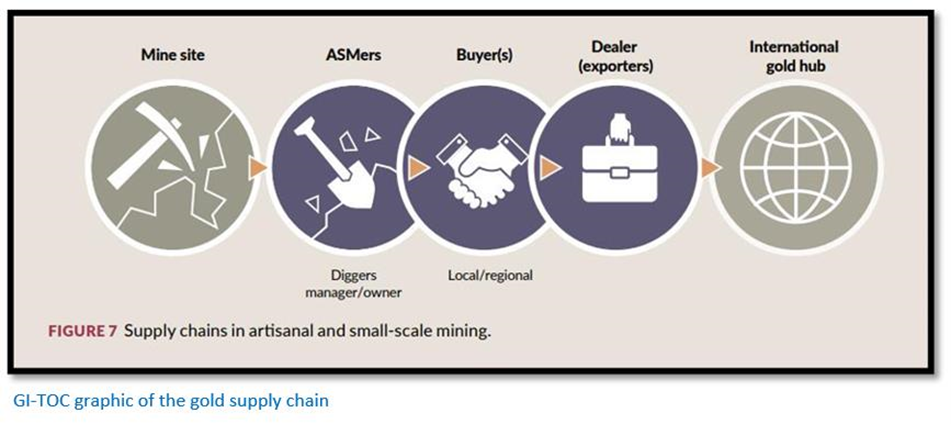

Typically ASM’s take the visible gold after milling and leave, usually paying 10% of the recovered gold as a milling cost. Often the millers are also gold buyers and miners can immediately exchange their gold for cash. However, much of the waste ore contains fine gold that can be recovered by the millers in a cyanidation process that recovers the minute gold particles not visible to the naked eye. Everyone who participates in the “syndicate” gets an equal share of the money earned after subtracting the sponsor’s costs when the gold is sold to a dealer.

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: Artisanal miner descending down a deep shaft

The vertical shaft will follow or hope to intersect a gold-bearing quartz vein that will be mined out, the quartz then carried in sacks to a mill where the rock will be ground to dust and then washed to separate the waste from the concentrate, the concentrate will be mixed with mercury.

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: manually crushing ore and by bore mill

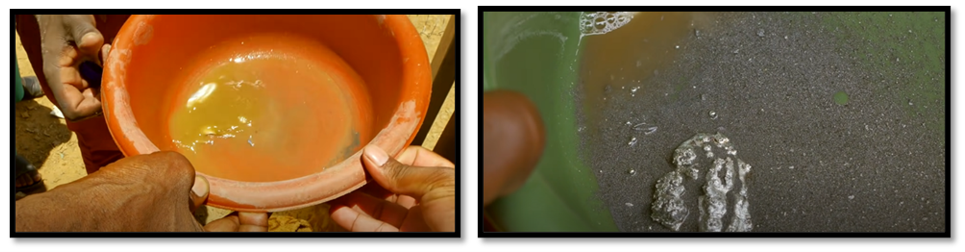

The mercury and gold then settle and combine together to form an amalgam and the mercury is then vaporised by placing it on hot charcoal or in a tin over a fire leaving the gold residue behind.

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: Mercury amalgamation, note the mercury droplets in the slurry concentrate

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: sluicing the concentrate to capture the gold in the fabric

Why do artisanal miners use mercury?

Although mercury use in gold processing is illegal in most countries, mercury amalgamation remains the preferred method employed by ASGM to extract the relatively fine gold. Assuming that ASM miners produce 30% of global production [much higher in Zimbabwe] and lose between 1 – 1.5 grams of mercury per gram of gold produced, it can be estimated that annually, between 800 and 1,000 tonnes of mercury are released to the environment based on world-wide gold production of 3,100 metric tonnes in 2022.[xiv]

The main reasons that mercury is so widely used by ASM gold miners are that mercury is easy to use, available, inexpensive and miners are not aware of, or choose to ignore, the health risks to humans and the environment.

The surface tension of mercury is greater than that of water, but less than that of gold, so gold adsorbs into the mercury. In addition, mercury acts as a dense medium; gold sinks into the mercury while the lighter waste material floats over the top. Most mercury comes from cinnabar ore mined in China, Spain, Kyrgyzstan and Algeria. Many artisanal miners appear to have less awareness or concern for environmental and health impacts of mercury than for other issues and probably the best way to persuade them to change their techniques would be via a social or cultural approach.

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: mercury in a pan prior to amalgamation: amalgam and concentrate

Mercury poisoning a serious ASGM occupational hazard

In some 50 developing countries worldwide, artisanal gold miners add mercury to the concentrate from crushed rocks or sediment containing gold. The mercury binds with gold particles like a glue, creating a mixture called amalgam. The amalgam is then heated to evaporate the mercury, leaving the gold behind. Inhaling mercury fumes when they evaporate poses the greatest danger to miners and their families. Extreme contamination can lead to organ failure and death, and pregnant women can pass exposure to their babies, causing neurological and developmental abnormalities.[xv]

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: Amalgam ball and burning off the mercury with an oxyacetylene torch

Of the total world releases in the range of 800 – 1,000 tonnes of mercury into the environment each year, approximately 200–250 tonnes are released in China, 100–150 tonnes in Indonesia, and 10–30 tonnes each in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Philippines, Venezuela and Zimbabwe.[xvi]

The Minamata Convention on mercury[xvii]

In 2013 Zimbabwe signed the U.N.’s Minamata Convention on Mercury, which holds governments responsible for protecting their people and environment from the toxic effects of mercury poisoning. Article 7 states “parties within their territory shall take to reduce, and where feasible, eliminate the use of mercury emissions and releases to the environment from artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) and processing.” Mercury use in ASGM is widespread in developing countries as there are few viable alternatives with two out of every three ASM’s using mercury.[xviii] Everybody wants to end its use in ASGM, but no single, non-toxic alternative currently exists to replace mercury and mercury bans risk depriving rural communities of this critical livelihood.

ASGM listed worst practices

Article 7 of the Minamata states the worst practices are:

(1) Whole ore amalgamation

(2) Open burning of amalgam or processed amalgam

(3) Burning of amalgam in residential areas

(4) Cyanide leaching in sediment, ore or tailings to which mercury has been added without first removing the mercury.

Many ASM’s will mix mercury with the concentrate after panning and roll the amalgam into a ball, and then with bare hands, the miner uses a cloth to squeeze the excess toxic mercury out of the amalgam and hopefully find a small mass of gold amalgam when he opens the cloth. Then, he will burn the gold amalgam ball to remove all traces of the mercury, sending toxic fumes into the environment, often without knowing that mercury exposure can lead to serious illnesses or even death.

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: Amalgam ball with the mercury being burned off on charcoal

Mercury enters Zimbabwe from the surrounding territories as an input necessity in the country’s largely unregulated gold boom. Linda Mujuru writes that mercury sellers simply show up and the miners buy what they need paying about US$200 per kilogram. Often a middleman will provide it for free in return for a discounted gold price.

Zimbabwe Pact found widespread use of mercury in ASGM and supported the government in developing a National Action Plan for mercury reduction. Pact also piloted low-cost fume hoods and glass retorts to reduce mercury exposure and delivered education and practical training to gold miners and refiners. But in reality the Zimbabwe government does little – if anything – to curb mercury use and instead encourages Zimbabweans to mine gold using any tools or substances they can.

Local communities are helpless, Mercy Bungu, a veteran gold miner told Linda Mujuru, “The water that we use to wash gold using mercury is the same water we use for drinking and cooking. We have numerous cases of children having [diarrhoea] because the water they are drinking is contaminated water.”[xix]

Dr George Mapiye, Mount Darwin’s district medical officer says, “People should use heavy-duty gloves and masks when they are using mercury.” But the ASGM camps near Mount Darwin where miners live lack even basic amenities. Those living there are on the edge of absolute poverty. They wear worn-out clothes that offer no protection from the weather or the conditions they encounter in the mines. Gloves, work suits and helmets (PPE) are the stuff of dreams.

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: the sprawl of an ASGM camp

The deadly effects of toxic mercury on individuals

Norman Mukwakwami, a project leader for the Zimbabwe Accountability and Artisanal Mining Program at Pact, says miners often can’t differentiate the symptoms of mercury poisoning from other typical diseases that include mental illness, miscarriage, male impotence, tremors and tooth decay are all symptoms of mercury poisoning.

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that inhaling mercury fumes or regular contact with mercury can each have devastating effects on the nervous system and prove fatal. The chemical quietly invades the body and leads to brain damage, developmental disorders in infants and young children, and irreparable kidney damage.[xx]

Many people affected by mercury are handling it at milling sites, but mercury also is consumed by humans eating fish that are living in mercury polluted waters. Water samples collected by the local district council from Lake Alexander at Penhalonga, which feeds into the Odzi and Mutare rivers found that mercury levels were nearly 150 times above the World Health Organization’s (WHO) drinking water guidelines.

Mercury poses a big danger to the environment

Elemental mercury, the liquid form, can travel through the air and settle on land or in water, making it a deadly threat to people and animals.

The United Nations Environment Programme says artisanal and small-scale gold miners make up the biggest source of mercury pollution in the world. It’s one of the few chemicals considered so detrimental that more than 100 countries have agreed to end its use.[xxi]

Linda Mujuru from Global Press Journal Zimbabwe interviewed Tembo, a 37 year old gold-buying agent, who was sick for a year. “At times l would wake up with a rash, tasteless mouth, slowness in speaking and loss of memory,” he says. He couldn’t get answers in Zimbabwe due to its deteriorating health care system, so after his blood tests were sent to South Africa they revealed the presence of the toxic chemical. “The doctor told me that I was very lucky to have survived this.”

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: Alluvial mining

The Zimbabwe government turns a blind eye to the continued use of mercury in ASGM

In Zimbabwe the government passed a law that bans mercury use in or near rivers, with a heavy fine and up to 12 months in jail. But artisanal miners are unaware of the law and the health risks from mercury and the government’s official gold buyer, Fidelity Printers and Refiners continues to buy ASM gold knowing mercury has been used in its extraction.

Farai Maguwu, executive director of the Centre for Natural Resource Governance, a Mutare-based non-governmental organization (NGO) wrote how officials buy gold without regard to its production, “Benefitting from economic activities that use mercury is illegal. Government is happy with the rise in gold output from artisanal and small-scale miners, and yet this gold is produced through the use of mercury.”

In government’s defence, Danmore Nhukarume, director of metallurgy in the MMMD said, “The convention does not say that you must eliminate use of mercury; because if we did that, these miners would now have to find some other source of livelihood. We cannot prescribe them to stop. We have livelihoods that depend on the [mining] sector. We must ensure that they are protected and we move with them as we transform from mercury use [to] mercury reduction to mercury elimination.”[xxii]

But those involved in mining see no real effort from the ZANU-PF government to stop mercury use. Lloyd Sesemani, the director of Zivai Community Empowerment Trust, an organization focused on transparency in the mining sector says, “It does not make sense to ratify international conventions without change on the ground or even informing the miners of these dangers or giving them alternatives.”

Lovemore Kasha, an advisor at Manicaland Miners Association, an association of small-scale and aspiring miners in Mutare says the government, “should be at the forefront to eradicate the use of mercury; so far they are not.” He uses mercury, he says, because he doesn’t have any other alternatives.

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: ASGM final product, gold mixed with other metals (doré)

Local people in eastern Zimbabwe hold state agencies responsible for environmental problems

Zimbabwe’s mining regulations state that no mining activity should commence before the Environmental Management Agency (EMA) issues an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) licence, a study used to assess potential environmental impacts and come up with ways to mitigate them.

But in mining areas such as for Penhalonga, activists and residents believe that the process was marred by massive corruption that influenced the outcome of the EIA. Both cyanide and mercury are supposed to be carefully monitored by the EMA to prevent their escape into the river system and dams, but the results at Lake Alexander in Penhalonga show these toxic compounds are spilling, threatening people and animals health.

Environmental agencies are hamstrung by politics

James Mupfumi, director of the Centre for Research and Development (CRD), a research institute based in Mutare said, “This is a creation of political elites in central government. Mining entities involved in mineral smuggling, tax evasion and environmental crimes in the area boast that they are protected by Zanu PF, the president, his family, other government elites and securocrats.”

Most local people interviewed voiced the same opinions[xxiii]

Photo UNESCO / MICA Miners Co-op Society: abandoned ASGM mining areas without any rehabilitation

References

F. S. Matiashe. 5 March 2023. IDN-InDepthNews. “We Are Drinking Mercury": In Zimbabwe, Artisanal Gold Mining Is Polluting Water. https://www.indepthnews.net/index.php/the-world/africa/5990-we-are-drinking-mercury-in-zimbabwe-artisanal-gold-mining-is-polluting-water

L. Mujuru. 23 Oct 2017. Global Press Journal Zimbabwe. With Economy in Shambles, Zimbabwe’s Gold Miners Risk Mercury Poisoning for Payday. https://globalpressjournal.com/africa/zimbabwe/economy-shambles-zimbabwes-gold-miners-risk-mercury-poisoning-payday/

L. Mujuru. Global Press journal Zimbabwe. 11 Jan 2023. Why Are Zimbabwe’s Gold Miners Risking Deadly Mercury Exposure. https://worldcrunch.com/business-finance/gold-mining-dangers

L. Mujuru. 3 Jan 2023. Global Press Journal Zimbabwe. Push for gold leaves a toxic legacy in Zimbabwe. https://globalpressjournal.com/africa/zimbabwe/push-gold-leaves-toxic-legacy/

K. Nyavaya and K. Mushauri. 18 Feb 2022. In Zimbabwe, High Unemployment Is Fuelling Informal Mining. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. https://www.rosalux.de/en/news/id/45975/in-zimbabwe-high-unemployment-is-fuelling-illegal-mining

M.M. Veiga, P.A. Maxson, L.D. Hylander. Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 14, Issues 3-4, 2006, Pages 436-447. Origin and consumption of mercury in small-scale gold mining. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959652605000752

Screen grab photos are from the UNESCO video: Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining: mining the gaps at: https://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-5270

Notes

[i] The term “artisanal and small-scale mining” (ASGM) includes small, medium, informal, legal, and illegal miners who use rudimentary techniques to extract gold.

[ii] According to the Zimbabwe Ministry of Mines and Mining Development

[iii] The current population of Zimbabwe is 15,478,162 as of Tuesday, May 9, 2023, based on Worldometer elaboration of the latest United Nations data.

[iv] Gutu, Angeline (2017): Artisanal and Small-scale Mining in Zimbabwe – Curse or Blessing?, https://www.parlzim.gov.zw/component/k2/artisanal-andsmall-scale-mining-in-zimbabwe-curse-or-blessing

[v] The Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions states the country’s unemployment rate is over 90%

[vi] Ministry of Mines and Mining Development: Zimbabwe’s Mineral Potential, online at: http://www.mines.gov.zw/mineral-potential/Thereareover4000,therichestint...

[vii] See the article Rushwaya gold-smuggling case exposes a microcosm of the corruption that exists in Zimbabwe today under Midlands province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[viii] Nyavaya and Mushauri found the Zimbabwe Miners Federation (ZMF) only represents registered miners, whose interests are usually detached from the actual needs of artisanal miners and they do nothing to encourage better conditions for artisanal miners.

[ix] Gold price at 10 May 2023 of US$2,023

[x] In Zimbabwe, High Unemployment Is Fuelling Informal Mining

[xi] Push for gold leaves a toxic legacy in Zimbabwe

[xii] Ibid

[xiii] See the article Zimbabwe’s illicit Gold Market hinders the country’s development under Midlands province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xv] PACT article GOLD. 3 Feb 2022. Miners use hazardous chemicals such as mercury and cyanide as part of the mining process in some 70 countries world-wide…. https://www.pactworld.org/search/node?addsearch=mercury

[xvi] Origin and consumption of mercury in small-scale gold mining

[xvii] Minamata is a Japanese town where many birth defects in children were detected that came from using water from a nearby heavily polluted lake with mercury

[xviii] With Economy in Shambles, Zimbabwe’s Gold Miners Risk Mercury Poisoning for Payday

[xix] Ibid

[xx] Why Are Zimbabwe’s Gold Miners Risking Deadly Mercury Exposure.

[xxi] Ibid

[xxii] Ibid

[xxiii] We Are Drinking Mercury: In Zimbabwe, Artisanal Gold Mining Is Polluting Water.