The Paper House (including the National Mining Museum)

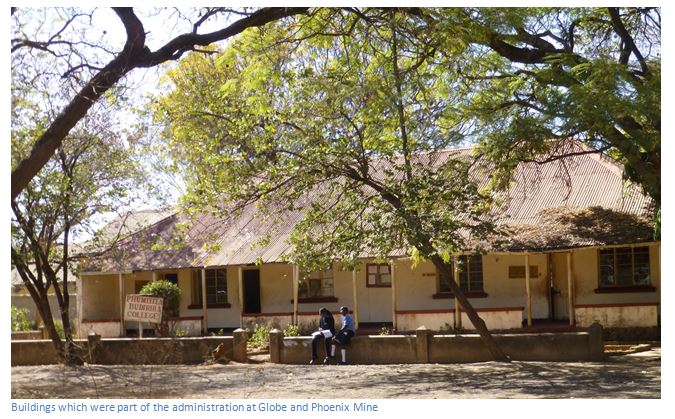

Kwekwe (formerly Que Que) has been linked to mining since ancient times and the National Mining Museum is very appropriately sited at Zimbabwe’s second largest gold producer, the Globe and Phoenix mine which produced over 4.2 million ounces of gold in its lifetime at an average grade of 27.6 grammes per ton.

The exhibits, all associated with mining, provide an insight into the complexities of mining and the degree of technical expertise required to win precious metals from great depths.

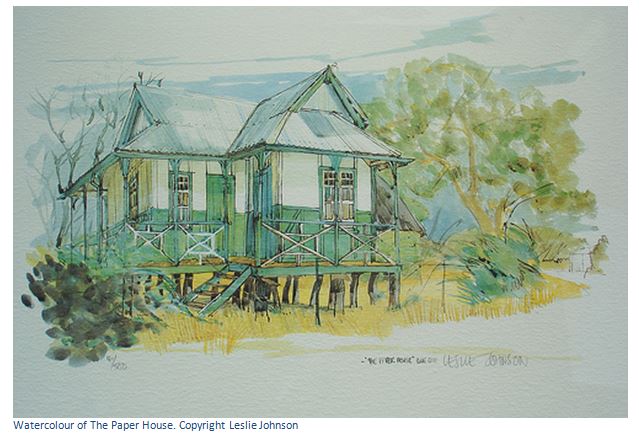

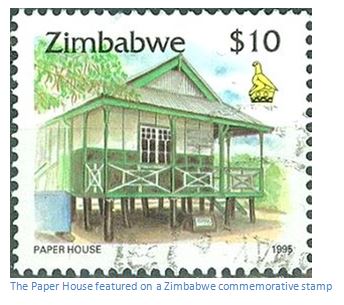

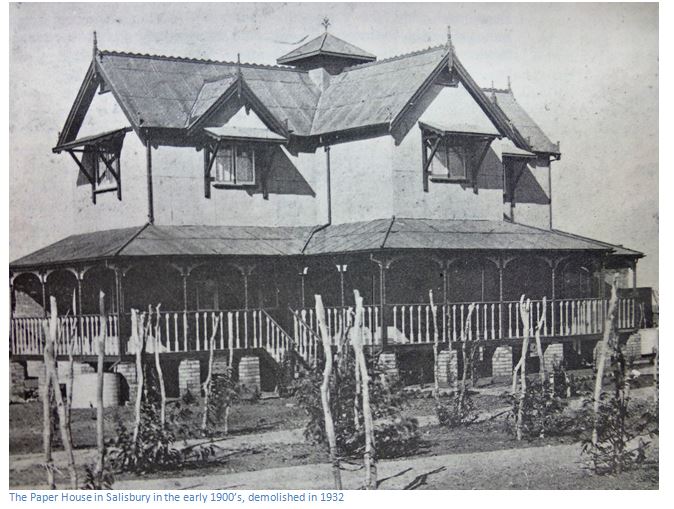

The Paper House is an amazing and unique historical relic from 1894. Other known paper houses imported in the early days are also mentioned with some photos of some early buildings.

From Harare take the A5 towards Bulawayo to KweKwe, through Chegutu and Kadoma, 213 KM reach KweKwe, 213.5 KM Pass the Mosque on your right, 213.7 KM turn right up 1st Avenue, becoming School Avenue, 214.2 KM turn right on gravel road at T junction, 214.4 KM follow gravel road bearing left to National Mining museum sign on the left.

From Bulawayo take the A5 towards KweKwe through Gweru, 226 KM reach KweKwe, 226.7 KM turn left up 1st Avenue, becoming School Avenue, following directions above

GPS reference: 18⁰55′30.31″S 29⁰48′03.22″E

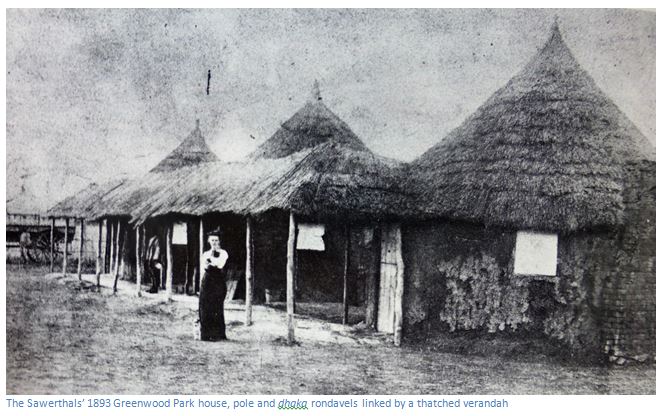

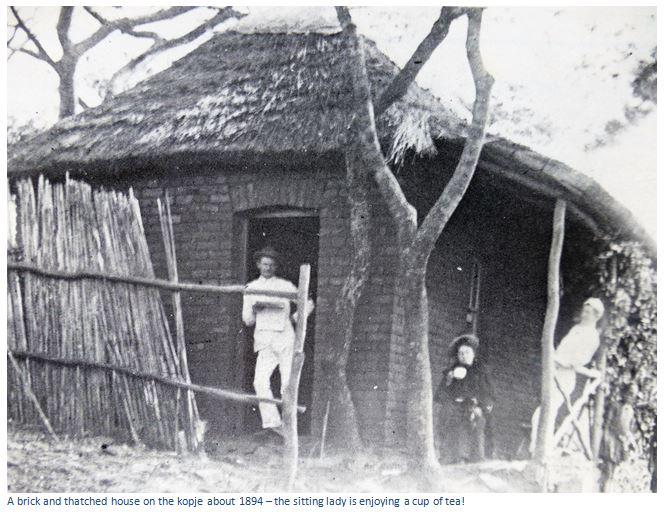

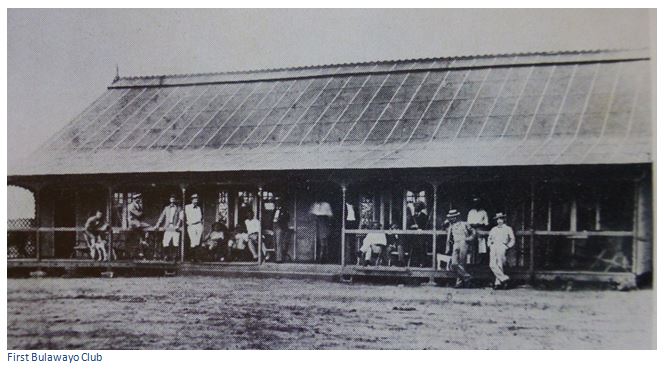

The Globe and Phoenix Mine discovery by Europeans was typical of many in Zimbabwe. In 1894, two prospectors, E.T. Pearson and J. Schakala equipped with little more than donkeys, blankets, prospecting pans and some supplies arrived in the district between the Kwekwe and Sebakwe Rivers. In exchange for blankets local Africans showed them some “ancient workings.” Pearson pegged the Phoenix reefs which extended in a double line for about 122 metres and followed the quartz down for 38 metres. Indications are that these miners were recovering over 28 grammes (one ounce) per tonne. Schakala pegged the Globe reefs where the ancient workings were over 200 metres long, but no deeper than 20 metres; the combined output at these sites from pre-colonial mining being estimated at over 1.4 tonnes (50,000 ounces) of gold. Both men registered their claims in Bulawayo in May 1894, but as they had no capital there was no possibility of either of them exploiting their finds. They planned to sell to the highest bidder and legend has it that Schakala initially tried to sell his claim for a case of whisky! In September 1894 both claims were bought by Lionel Phillips who later wrote: “I met a prospector named Pearson who told me of a very large old working he had pegged. This country was very little known. We travelled on horseback with pack donkeys. We examined the old workings and were able to go down over 100 feet in one part and found the reef as it had been left by the ancients. In many parts you could see the reef at from 30 to 50 feet in depth. This was the Phoenix reef. About 500 yards distant was the Globe reef which had been pegged by Schakala. No work had been done on either of the properties by the prospectors. I returned to my camp at Gwelo with Pearson and Schakala and eventually bought both the Globe and Phoenix reefs for the Phillips Exploration Syndicate.” The Globe was bought for £300 cash and 500 on £1 shares, the Phoenix for £600, the cash paid in gold sovereigns at Shepherds Beer Hall in Gwelo (now Gweru) where many business transactions took place in those days. So favourable was the 1895 consultant’s report that Lionel Phillips left immediately for England to float the Globe and Phoenix Company which was incorporated on 18 October 1896 with a capital of £175,000 in £1 shares. By 1898, after delays due to the Matabele Uprising / Umvukela and an outbreak of rinderpest which killed all the oxen used to pull the ox-wagons and the need for the construction of an eight kilometre pipeline for water from the Sebakwe River the erection of the gold processing plant began. The forty stamp mill produced the first gold in August 1900, although the outbreak of the Anglo Boer War prevented the cyanide plant from being delivered. By 1935 the Globe and Phoenix mine had produced nearly an ounce of gold for every ton milled and was described as the highest grade mine in the world and included amongst its Directors the Governor of the Bank of England. The National Mining Museum also has a display of a Mashona iron smelting furnace and explanation of how it was used for smelting and forging and the useful iron tools, such as hoes and spears that were produced. Most of the mining equipment now on display relates to the post 1900 era and includes hand operated stamp mills, as well as belt-driven models powered by steam and later electricity, plus all the associated equipment required in mines such as pumps, compressors, crushers and rock-drills. Mining, both legal and illegal, has been and will continue to be a major contributor to the national economy. Early miners and prospectors in the 1890’s initially lived in their tents, or on their ox-wagons until they had African builders put up thatched pole and dhaka huts for them. These soon gave way to sun-dried (Kimberley) or kiln-fired brick walls built with grass thatched roofs. Roofs remained thatched until corrugated iron sheets, tools and nails could be brought into the country by ox-wagon from South Africa, or from Beira. Once regular supplies of materials were available, some buildings were built with corrugated iron on a timber frame for both roof and walls as these were light and portable and could be moved to a new location. Corrugated iron walls was used more for shops, churches and government buildings than for domestic homes as they were hot in summer and cold in winter. For an example, see the prefabricated barracks at the Morris Depot under the Harare – Avenues article. These prefabricated buildings could be ordered from merchants catalogues and were not only in corrugated iron. At least two examples of other “Paper Houses” are known to have existed…a double storey house was built in 1894 from prefabricated wire-woven compressed boards. “The Paper House” in Harare (formerly Salisbury) was built by E.A. Maund, also responsible for “The Residency” and the “Market Hall” in 1894, on the corner of Samora Machel Avenue / Fifth Street on the site of the present day Holiday Inn. The structure was imported from Britain in prefabricated panels of wire woven paper and assembled around a timber frame. Like the Paper House in KweKwe, it was lifted off the ground, in this case by brick piers, to protect it from termites and the weather. The Harare Paper House was built for the BSA Company as the Senior Judge’s residence; later it was later a Women’s Hostel, a Nursing Home and finally the Manor House Private Hotel. The first Bulawayo Club, of which Rhodes was a foundation member, no longer exists; but was also a paper building on the corner of Main Street / 6th Avenue. The same site was later where the British Empire Service League later built the Empire Club. The second Bulawayo Club was granted two stands by Rhodes on the corner of Main Street / 8th Avenue and construction began in 1896. The incomplete building was used as a troop’s barracks during the Matabele Uprising / Umvukela and suffered considerable damage before completion in August 1896. The Bulawayo Club moved to its present site on Fort Street / 9th Avenue in May 1935. Mirleen Atkinson, the wife of a former Globe and Phoenix Mine Manager in her interesting article says that the original Kwekwe was a small police fort based on the river of the same name fifteen kilometres south of the present Kwekwe, which was then called Sebakwe, but with the development of the Globe and Phoenix Mine, the few inhabitants of the original Kwekwe began to drift over to Sebakwe. In 1895, a post office was established there, then separate African and European hospitals and on 5th November 1901 the railway line was connected with Salisbury (now Harare) and in the following year to Bulawayo. Before this, the journey to Gweru by donkey cart took three days; now the rail journey took four hours as long as the engine driver was not tempted by a herd of antelope to stop and shot an animal “for the pot.” One Kwekwe inhabitant remembers a train journey when the train was stopped to allow two men in a violent argument to settle their difference in a fistfight! The first butchery and general store opened in 1902, but the mine opened its own general dealers store the next year and brought down the often exorbitant prices which had been charged previously. A mine club was opened in 1902 with a bar and billiards room and there were two enthusiastic cricket teams and a rugby team. An away game in Bulawayo entailed taking a week’s leave with the journey time! On 20th August 1902, Sebakwe was renamed Que Que (now Kwekwe) and a village management board took over with the general manager of the Globe and Phoenix mine as first chairman. By 1903, there were eighteen European women resident. The mine continued to prosper and additional mine workers had to be recruited as far away as Zambia and Malawi. On the 3rd February 1905, the mine surface magazine with about seven tons of explosive accidently blew up causing a huge crater and shaking the town and blowing all the liquor bottles off the shelves of the Mitchell’s Hotel. By 1909, the Globe and Phoenix was in full production. Many claims were pegged as close to the Globe and Phoenix (G&P) as possible and a dispute arose in 1914 when Amalgamated Properties of Rhodesia Ltd sued the G&P for a half share of the gold extracted from a vertical of the John Bull Block that intersected the Phoenix Parallel. The court case was the longest and most costly in the history of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and England and went all the way to the House of Lords in 1919. It was known as the “John Bull” case. Mr Justice Eve listened to Mr Upjohn’s appeal speech and wrote some poetry, the last verse of which reads: Tell me the same old story Of fissure veins from hell, Of Phoenix and its glory The Main and Parallel. The second case was in 1933, when Rhodesia Corporation Ltd, (successors to Amalgamated Properties) claimed the G&P Phoenix parallel was encroaching on their Northern Extension Reef. The courts ruled in favour of the G&P in both cases. Mirleen Atkinson writes that when the 1918 flu pandemic which ran from January 1918 – December 1920 affected Que Que severely. Of the four hundred underground workers, only nineteen turned up for work with most of the hospital staff ill and Dr Davey himself administering help and advice from his sick bed. The Club hall became a temporary hospital and ten of the G&P’s European staff died and about three hundred Africans.

References Diana Polisensky (www.oncecalledhome.com) P. Jackson. Historic Buildings of Harare. Quest Publishing 1986 R. Summers. Ancient Mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia. 1969. M. Atkinson. History of the Globe and Phoenix Mine. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No.16 1997 P67-72 C.K. Cooke. Some Buildings and Sites near Bulawayo connected with C.J. Rhodes. Rhodesiana Publication No. 35. September 1976 |