Gweru Memorial (Matabele uprising, or First Umvukela, 1896)

Various Memorials were set up by the Rhodesian Memorial Fund in 1896 with the purpose of commemorating those military and civilians who were killed in the Matabele Uprising, or First Umvukela of 1896. The Funds also had the aim of providing for those who were wounded, or made destitute and the wider aim of providing libraries, museums and hospitals.

In an article in Rhodesiana No. 22 called Memorials: Matabele Rebellion 1896 (P16-19) by C.K. Cooke, he states there were four Memorials erected at outlying points in Matabeleland by the Rhodesian Memorial Fund as follows:

(1) Pongo (National Monument No. 33) near Shangani. See my separate article under Matabeleland South.

(2) Filabusi (National Monument No. 56)

(3) Mambo (National Monument No. 57)

(4) Fort Rixon (National Monument No. 58) south of Fort Rixon, sometimes called the Claremont Mine, or Cunningham Memorial, to the nine members of the Cunningham family. See my separate article under Matabeleland South.

This Gweru Memorial was set up by the Pioneer Memorial Fund; this is not carved into the memorial, but does appear on the east facing metal plate beneath; however I have been unable to trace any further information about this Fund. The Memorial is made from the same red sandstone as the four above, with an obelisk set upon a plinth upon which the names being commemorated are carved. The article by C.K. Cooke makes no mention of the Gweru Memorial, although the similar style and materials suggest they are probably roughly contemporary.

Situated at the entrance to the Zimbabwe Military Museum. Lobengula Avenue, Gweru, on the eastern side of the Civic Centre. Lobengula Avenue runs parallel and east of the A5 as it heads out of Gweru for Bulawayo

GPS reference: 19⁰27′37.82″S 29⁰48′55.55″E

List of Victims named on the Gweru Memorial | ||

Names | Date of Death | Details |

Military |

|

|

Arnold, James Carlisle | 01 August 1896 | Tpr in the Gwelo Field Force, died in Gwelo Hospital of jaundice |

Clarke, William Herbert "Nobby" | 05 June 1896 | Gwelo Field Force, no details given |

Hays or Hayes, Dan Joseph | 29 July 1896 | Volunteer aged 43, Cpl in the Gwelo Field Force, KIA on Hurrell's Patrol at Sinanko kopje |

Keirchbaum, George | 07 August 1896 | Tpr in the Gwelo Field Force, died in Gwelo Hospital of fever |

Lomgton, Frank L | 2 June 1896 | Gwelo Field Force, died in Gwelo Hospital of fever, also known as Frank Leighton |

Mathieson, Robertson Balfour | 21 July 1896 | Tpr in the Gwelo Field Force, aged 24, KIA on Hurrell's Patrol in the Bezwy Hills |

McLean, Malcolm Robert | 06 June 1896 | Tpr in the Gwelo Field Force. Death certificate states born in Canada. Aged 28 years and listed as a storekeeper. Died in Gwelo Hospital of enteric fever. |

McVean, Archibald | 28 April 1896 | Tpr in the Gwelo Field Force. Death certificate states he was a miner and aged 25. Died in Gwelo Hospital of fever and dysentery. His effects are listed as a metal watch and chain, a packet of letters and photos. |

O'Farrell, J.P. | 22 April 1896 | Tpr in the Gwelo Field Force, died in Gwelo Hospital of pneumonia. His death certificate lists him as aged 43 and as a general labourer. He had no will and his effects when sold realised £1. |

Selous, Edric Nugent | 9 May 1896 | Tpr in the Gwelo Field Force, died in Gwelo Hospital of fever. His death certificate states he was a prospector, aged 24. His effects are listed as two letters. |

Soman, Edward | 12 September 1896 | Tpr in the Gwelo Field Force, died in Gwelo Hospital of pneumonia: his death certificate says camp fever. Effects listed as two letters |

Storey, Charles Frederick | 04 June 1896 | Tpr in the Gwelo Field Force, died in Gwelo Hospital of acute malarial fever. His death certificate states he was 31 and a storekeeper. Effects listed as two letters. |

Talbot, Frederick Walter | 11 September 1896 | Cpl in C Troop of the BSAP, KIA at Uwini's Camp |

Civilians |

|

|

Anderson, Jocelyn Hepburn | end March 1896 | Sebakwe, on his way to Mafungabusi, engineer |

Barr, Robert A. |

| not listed in the '96 Rebellions |

Bowen, James | 30 March 1896 | Maven, killed with Van Blerk at Hammond's Mines |

Bowker, Fred J. | 30 March 1896 | Lower Gwelo, sent to warn civilians, Tpr. In M.M.P. |

Barnard, Harry Edgar | 25 March 1896 | Umvunga, partner at Umvunga Store with West Bros. |

Clark, W.E. | end March 1896 | Maven, body found by Gwelo Patrol. |

Durden, Charles John | 25 March 1896 | Ingwenya, killed with surveyor Fitzpatrick |

Dixon, W.C.B. |

| not listed in the '96 Rebellions |

Dufva, Wilhelm | 30 March 1896 | Shangani, listed in '96 Rebellions as Dupua |

Edgell, Edward Ramsay | end March 1896 | travelling from Gwelo to Hartley Hills, formerly (1895) Sub Commissioner BSA Police, Fort Tuli |

Fitzpatrick, T | 25 March 1896 | Ingwenya, killed with Durden, surveyor |

Farrar | end March 1896 | Lower Gwelo, prospecting with companion, name unknown |

Grenfell, Pascoe St. Leger | end March 1896 | Ingwenya, Manager Murray-Gourlay Co. |

Harbord, Horace M. | end March 1896 | Ingwenya Store, old Hunters Road to Hartley Hills |

Hartley, Joseph | end March 1896 | Maven, killed with J. Stobie, both working for G.R. Lennock |

Ireland | end March 1896 | Ingwenya, body found with Harbord's. |

Kerrigan, Frank |

| not listed in the '96 Rebellions |

Lennock, George R. | end March 1896 | Maven |

Lee, Albert J. | end March 1896 | Umniati, sailmaker |

Milford, William B. | end March 1896 | Gwelo |

MᶜCormick, William | end March 1896 | Ingwenya Store, working for H.B. Taylor. Name spelt MᶜCormack in '96 Rebellions |

Stanley, Frank Harrison | end March 1896 | Sebakwe |

Stobie, James | 25 March 1896 | Maven, killed with J. Hartley, both working for G.R. Lennock |

Sneddon | end March 1896 | Maven, sick with fever at the time |

Van Blerk, Richard B. | 30 March 1896 | Maven, killed with J. Bowen at Hammond's Mines |

Whylie, David | end March 1896 | Gwelo, working for Warwick & Celliers, spelled Wyllie in the '96 Rebellions |

White, Robert | end March 1896 |

|

The following military from the 7th Hussars are known to have died, mostly at Gwelo hospital at the same time, but were not commemorated, presumably because they were not military volunteers, or civilians, resident in the country at the time of the Matabele uprising, or First Umvukela.

Corney, George | 19 September 1896 | Tpr, D Sqn 7th Hussars, died of typhoid in the Shangani area |

Jay, Leonard | 19 October 1896 | Tpr, A Sqn 7th Hussars, died of enteric fever at Gwelo Hospital |

Mc George, Ernest | 29 October 1896 | Tpr, A Sqn 7th Hussars, died of enteric fever at Gwelo Hospital |

Parrett, J. | U/K | L/Cpl, U/K 7th Hussars, died of fever at Gwelo Hospital |

Usborne C. | 10 October 1896 | Tpr, A Sqn 7th Hussars, died of enteric fever at Gwelo Hospital |

Willard, George | 10 November 1896 | Sqn Sgt Major, A Sqn 7th Hussars, died of enteric fever at Gwelo Hospital |

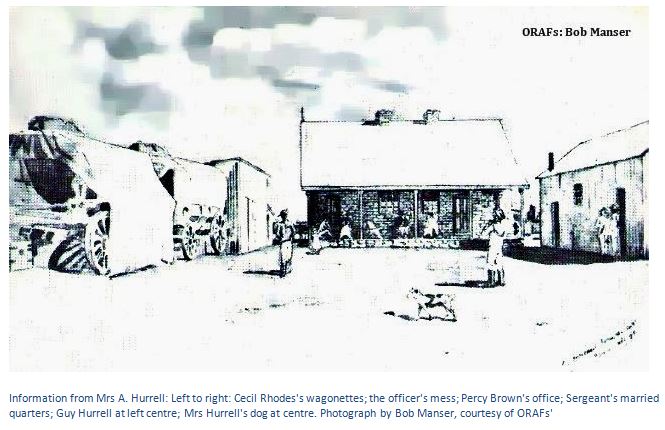

One of the best and most personal accounts of the event is written in Rhodesiana No. 22 of July 1970 and was submitted by Mrs A. Hurrell, who with her husband, William Hurrell, were prominent early citizens of Gwelo (now Gweru) and is from the pencil-written diary of Peter Falk who was present in Gwelo at the time. [Note1] His British South Africa Company Medal 1890-97, reverse Rhodesia 1896 (Burgher P. Falk, Gwelo Burghers) with several photographs of him and his family and letters and papers regarding his service with the 1896 Rhodesian Volunteers and a letter to accompany the B.S.A. Medal from Government House, Cape Town, dated 17 June 1899; together with the typescript: ‘Gwelo Lager’, ‘probably written by Mrs L. Bagnall with Mr Peter Falk’s help’ were sold at auction in South Africa in December 2012.

First, some general background to the events. All the small settlements on farms, mines and trading stores in Matabeleland quickly became abandoned. As F.C. Selous in Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia so graphically puts it: “There is reason to believe that the outbreak of the rebellion, commencing as it did with the murder of a native policeman on Friday, 20th March [1896] was somewhat premature, and thus there was an interval of nearly three days between the date of this murder and the day when the first white men were killed by the natives. From the Umzingwane, the flame of rebellion spread through the Filabusi and Insiza districts, to the Shangani and Inyati, and thence to the mining camps in the neighbourhood of the Gwelo and Ingwenia rivers, and indeed throughout the country wherever white men, women and children could be taken by surprise and murdered either singly or in small parties; and so quickly was this cruel work accomplished, that although it was only on 23rd March that the first Europeans were murdered, there is reason to believe that by the evening of the 30th, not a white man was left alive in the outlying districts of Matabeland.”

Gwelo remained in contact with Bulawayo by telegraph, which was only cut by the Matabele on April 1, and knew of the start of the uprising on March 25, when urgent messages about Bulawayo’s situation were received almost at the same time as the accounts of killings and burning of property were received from Shangani.

Gwelo town went into laager that night, but were not prepared for any attack, as they had just 40 rifles and 2,000 rounds of ammunition between them. When Salisbury was informed by telegraph of their desperate situation; Captain Gibbs was immediately sent in a coach with 12 men and two Maxim guns, 50 rifles and 21,000 rounds of ammunition. They arrived at Gwelo on 29 March to find 350 men, 27 women and 22 children were taking refuge in the laager. Within a week Gibbs had formed the Gwelo Volunteers (later the Gwelo Field Force) with 284 men.

Soon after his arrival at Gwelo to take charge a diarist recorded: "Captain Gibbs disgusted with state of laager, formed fatigue parties and commenced fixing us up, it's a Godsend he came to camp". A week later, the laager was fortified and in good order. Like his colleagues in Bulawayo, Gibbs began patrols into the surrounding countryside, but was beaten back by men from the Amaveni Impi, who fired upon the first patrol on March 30 and two days later attacked Gibbs's "friendly" Shangaans, who were nothing more than mine labourers, killing 20. Gibbs counter-attacked, but was forced to remain into laager after April 22.

Capt. J. A. C. Gibbs appears from his own and other diaries to have been a most enthusiastic fort builder. On May 20th, Gibbs left Gwelo with a force of 66 troops and 120 others to prepare a fort controlling the Charter-Salisbury road and chose a site for the future Fort Gibbs two days later at Makalaka Kop, a low but commanding kopje where, three weeks before, the Salisbury Column on its way to Bulawayo had skirmished with a Matabele force, and which dominated the rebel grain lands. [Note 2]

On June 25th, 1896, Gibbs left a garrison at the fort and went on to Shangani, on the Bulawayo-Gwelo road, where a standard circular earthwork fort was erected, again at a site where the Salisbury Column had reported a strong Matabele concentration. [Note 3]

The Gwelo laager was situated at the corner of Lobengula Street and 5th Avenue – where the main Gweru central Police station is today with a well located at the north-west corner.

Peter Falk’s diary recounts: Life was quite an uneventful business in Gwelo until the 25th March 1896, when rumours of a native rising were wired to us from Bulawayo. There was a public meeting held in the morning and one of the members was sent around to warn all the families, which were then eight in number, to be prepared for the word, which meant to go into laager. Meanwhile the men here took things into their own hands and gave themselves good … in case war did break out, and began moving wagons, etc. to form a laager and sending out warnings to the miners and prospectors all around the Gwelo district to come in at once. In the afternoon women went around condoling with each other, and some who had experienced laager life before (having been in Victoria during the last war) rather looking forward to it as “good fun.” In the evening few undressed for bed as the call to laager might come at any time, so the children went to bed in their clothes, and the elders anxiously waited. At 11pm a sharp knock at the door and “into laager as good as you can” was the order. Wraps, rugs, pillows, etc. were hastily put together, and then for laager, which was composed of private offices and Government buildings which faced each other, and wagons drawn across the open ends.

The excitement was intense, every face anxious, both of men and women, as they all knew the ammunition would only last 15 minutes if a rush were made by the natives.

The women and children were all put in one large and one small room. The large from the verandah which opened into the laager square and the small one out of it. There were eight women and eleven children, the latter varying in age from two months to fourteen years of age. Never were a braver set than these, though they knew what the consequences would be if the natives attacked that night.

The window of the large room was thrown open, and some of the women sat at it all night chatting quietly to the men, who were all in the laager square with their rifles, revolvers and bandoliers.

Beds were made up on the floor of the room for the children, and those of the women who could sleep; and really, the behaviour of all was truly grand. Some of the women had been too hurried to bring even a rug or pillow, and these were at once lent by others who had come well provided, so that women met and were as one in the common trouble though never having exchanged a word before.

The men were on the qui vive [the alert; lookout] all night as there were so few, and so the day slowly dawned, and all thanked God for their safety.

After the sun was well up they were allowed to return to their homes, but told to be ready to run for laager on the least warning and to be back with proper bedding at 2pm. It was a strange scene, all the men and women and children separating and going to their homes, looking not very fresh and bright after their night’s watching.

On reaching their houses very few native servants were to be found; they having almost all having returned to their kraals of which the greater number were in this district. So another trouble awaited the poor tired women. However, there was nothing for it but making the best of things and the cheerfulness of all was remarkable.

The inhabitants near Gwelo now began to come, and from then until a week after, the wagons, light traps, scotch carts and indeed every kind of conveyance in the District came pouring in.

At 2pm according to order, the inhabitants all reassembled in the laager which had been assuming a most formidable aspect, and found that they were all allotted rooms, or share of rooms; two families consisting of two mothers and six children sharing one average room and so on.

There was a time given for preparations for the night, and orders were again given to all, be back before dark, as the natives don’t like attacking by day; and their movements are always guided by the moon.

In the afternoon of the 26th March, the residents and miners from Selukwe, 25 miles off arrived, most of the men walking and the women and children on wagons; all looking very jaded and travel-stained and glad to get here. Then came the difficulty of housing them, but by degrees by putting up tents and drawing the tented wagons in close, they were all accommodated.

Meanwhile [telegraph] wires were coming in of murders on all sides, and the excitement was dreadful.

One of the police was sent with a volunteer on one direction in order to warn a few men in the Maven District, 18 miles away, of course both fully armed and on good horses. On their way they fell in with natives who fired at them, but missed; they returned the fire and the natives fled, and a lucky thing they did, for in the last shot, the policeman’s revolver jammed, and on his opening it to find the cause, the charge exploded and went right through his right hand.

Here was a dilemma, the policeman could not mount, and the volunteer did not wish to leave him, not knowing when the natives might return. At last they decided the best thing was for the volunteer to ride for aid. When he arrived [back in Gwelo] there was excitement, for the natives were not known to be so close. Immediate help was sent and a cart; and when the escort guided by the volunteer reached the place where he had left his companion, they saw his cloak under a tree, and not the man. They at once concluded the natives had returned and murdered him, when fortunately they heard a cry, and in looking in the direction of the sound there was the policeman who had got under a tree both for protection from savage and sun. The wounded man was weak from loss of blood, but fortunately there were good surgeons and his hand was eventually completely cured.

Next day a messenger came from the same direction, saying that there were six whites and some Cape boys 8 miles out and they could not get any further, being foot sore and worn out. Help in the shape of a light trap for six, with ten mules and an escort was sent to them; and they arrived about six hours after with a terrible tale.

One of these was a Government Mine Inspector who had received an assegai wound in the shoulder, and he told us of how it had happened.

He had been inspecting mines in a camp which also boasted a store, and in the evening the different miners and the … and to the store for a chat, having heard nothing of the uprising. They were all together having a chat, with the exception of a young Government Land Surveyor, who had retired to his tent a short distance away. The first warning the men in the store had was a bursting of the door and a body of armed natives trying to rush the store, one of them flinging an assegai at the Mine Inspector, whose back was to the door and who had no time to turn. This would have been fatal, had not the store man … the arm of the thrower, and so spoilt his aim. As quick as lightning almost, the whites rose and seized their guns which are always handy here, there being so much game, and no sooner did the natives see the guns than they turned and fled. After their astonishment had cooled a bit, the men thought they would go and warn the young fellow in the tent, and when they reached the place and looked in, there was a ghastly sight.

The poor young fellow had two spear wounds, one in his heart and one in his throat, so death must have been instantaneous. [Note 4]

There was neither time, nor means for burying the poor boy properly, so they did their best, and then started, in the middle of the night, for Gwelo. One young fellow was in such a hurry he could not find his boots, and the only one with a horse was the Mine Inspector, so he gave his boots to the one who had none. They took a track across country to avoid the natives who were probably near the roads and tramped through the long grass, as quietly as possible. When you know that lions are common in all these parts, then you may imagine how these men felt.

They came to within six miles of Gwelo like that, and then sent the least tired man on the horse, to ask for aid. The one man’s feet were dreadfully cut up by the long grass, and the Mine Inspector’s wound, though luckily only a flesh one was very troublesome for some time.

Things like this happened every day and wires of fresh murders between here and Bulawayo where the natives placed grass on their victim’s faces, after they had chopped them all over, and set fire to the grass, so that the features would not be recognized, set all the men, and I am afraid, the women too, longing for revenge.

As soon as possible, the local authorities wired to Bulawayo for ammunition and, if possible, men, the answer was; “not sufficient ammunition for ourselves and no men can be spared as the natives are in open rebellion here and in the Matopos: ask Salisbury.”

Reply from Salisbury was; “will send officers, two maxims, and sufficient ammunition at once.”

As Salisbury is 180 miles away, and nothing but mule transport, it took four days to come, and there we were during all that time in a fever of anxiety, knowing if attacked boldly, it would be all up with us.

As soon as possible, the hospital was put in order. The way this was done, was to take the Government Offices which we had used the first night in laager, and put beds etc. in them ready for either fever or wounded patients. Most of the ladies did good service in this department, as, until the Dominican Sisters arrived, they did all the nursing. The Doctors were also anxiously doing their best, and as this was the fever season, there were soon a good number of patients to attend to.

Then there was the provisioning of the laager, co the Commandant took over the contents of the three stores in the place, and started rationing the people.

There were thousands of cattle close in on the commonage having been brought in by farmers in the District and as these were also taken over by the Commandant at a certain price, there was no lack of meat, and in fact there was too much of it, heaps being wasted, even by the native servants, who as a rule, cannot get enough meat to satisfy themselves with.

Then the rinderpest arrived on the scene. It had been in Matabeleland, but not reached us before.

The cattle (oxen, cows and calves) were driven into an immense kraal at night for safety from the natives, who might otherwise have easily driven them off any dark night, and as their only wealth lies in cattle, this was something to take into consideration.

Well the rinderpest arrived, as I said before, and at once played sad havoc among the cattle; sometimes as many as eighty and one hundred carcasses having to be pulled out of the kraal in the morning; this was bad news for us all, and the milk which we had all been getting from the cows had to be discontinued, as the Doctor did not think it advisable for it to be used; then some person got the idea that the flesh of these animals, thought perfectly well when killed, must somehow have the disease also; and as there were so very many down with fever, which had several symptoms, they said the meat was the cause of it, and that the people were really ill with a sort of rinderpest.

Another large party now arrived from Shangani. This river and district will be remembered as the scene of Major Wilson’s death, and also of another battle higher up the river. Several wagonettes and wagons, the former belonging to Willoughby’s, made a good addition to the laager both in numbers and ammunition, etc.

There was a family, in a wagon, consisting of parents, grandparents and four children with this party, and the women told that they had a lovely farm in the Shangani District, and had it stocked, and were very comfortable when one morning while resting quietly at breakfast, a messenger rode up in hot haste to warn them. He said the natives were not far off; so these poor things started up from breakfast, and while the father had the mules put onto the wagon, the mother and grandmother got some bedding and a few clothes together, and the family started in a very short time. As they left the farm, in the distance, they saw thick columns of smoke rising, and knew by that sign that the natives had arrived, and finding their buggy gone, had at once fired the place, which being thatched with grass was soon in flames. The woman said the loss she and her mother, who belonged to one of the good old Cape Dutch families, mourned most was a box of very old silver that had been in the family for generations.

They also told me of the murder of her husband’s sister who was married and living on the next farm to them, and who had been warned, but too late, for afterwards her body was found lying under a bank of the river, where she must have run to hide, and the bloodthirsty savages followed her footprints, and simply chopped her about so that if it had not been for her rings, she would never have been identified. [Note 5]

After such things as these can you wonder at any ill treatment the natives may receive, though I know now that the war is almost over, and these same natives will be sent as servants, to us all, that their lives will be very easy lazy ones, the whites being most forgiving. The coach with officers and maxims arrived in good time, and you may imagine our joy and relief, was also sent an Imperial Officer to take charge of the District, so things which had been “going slow” now moved fast. The first thing he did was to find out which men were Volunteers and which Burgers, as all the men in the laager now numbered 400, there was quite a good show.

The Dutch of the settled inhabitants remained Burgers, though this officer did his best to enrol them as Volunteers; the reason being that much more control can be exercised over Volunteers than over Burghers. The latter only serving for the defence of the place. The Burgers, among whom were some of the best men, were very indignant with this officer, who said they were only “camp followers.” However, he remained long enough with us to regret his words. [Note 6]

An order was given, which has since been regretted; this was to pull down all the houses within a certain distance of the laager, so as to leave no cover for the natives, should they attack us. So, as Gwelo was not a large village, this reduced the houses to quite one half. They were mostly wood and dagga, a mixture of clay, and thatched, so a few fatigue parties soon demolished them, but the burning of those houses gave the natives courage, as we afterward heard them saying we must be afraid of them to pull down our houses.

Almost every morning there would be native servants missing and of these … went to their own tribes nearby, with the latest news. You may ask were we not afraid to have these men near us; but we had not the least fear of them singly, the danger lay in the masses they would meet us with.

The order for this rising, we have heard since, was sent to all the different Indunas or Chiefs, and this was, that when the moon had reached a certain stage, each man who was in service should rise on this particular night and murder his master, and then the country would be their own again. As the natives were in such tremendous majority this could easily have been accomplished and it would have meant total annihilation of the white population. Fortunately there were some misunderstandings as to the exact date and so these murders took place at different times; but almost all within the first week.

Of course in a place like a laager where everything one did or said was generally repeated, with as you may be sure, no deductions, there soon arose a sore feeling , and as the so-called Military were in fact Volunteers, only one was an Imperial Officer, who tried to make a distinction between the masses. This was a great mistake and I know some, though they said nothing, felt it very keenly; but we all know “ a little power is a dangerous thing.”

The next excitement, some queer incidents arose, for instance … About the day after the Public Houses (they are not worthy of the name of Hotels) were burned down, the boarders at the different Inns had to find new homes. One of these came to a friend’s house early in the morning and asked in a very pathetic way if they would give him a cup of coffee and a bit of bread. Well you can imagine what the feelings of this man must have been as he was very refined and sensitive, to have to do that. He was at once chided for not coming before and taken as a member of the Mess; for this he is even grateful yet. The B.S.A. Co. behaved splendidly and gave us all necessities free, and in that and other things they have been so generous that I am sure few Rhodesian settlers have anything against them; excepting taking the Police away.

Our Imperial Officer was a very thorough, hardworking man and commenced a flag signalling class from hill to hill, and in drilling the men both Infantry and Cavalry every day, until they began to have quite a martial appearance, if it were not for the clothes. I remember an incident relating to clothes.

I think it was when Mr Rhodes, our uncrowned King was expected. The men were all on parade and the Officer asked them to put in as good an appearance as possible, and to wear coats. Several remarked, sotto voce, “we have no coats and there are none to spare.” So they were forced to appear in shirtsleeves. These men had been forced to leave everything and fly for their lives at the Outbreak. Mr Rhodes then arrived with Officers, Volunteers and Dominican sisters after a tedious journey; the cattle dying by fifties all along the march and their having to be replaced caused the journey of 170 miles to take weeks instead of days. All Gwelo turned out to meet “Our Hero” for, let outsiders say what they like, he is that to us all.

The arrivals all looked very fit and drew up in good order. Our men were standing at attention and when Mr Rhodes drew up and began to make a short speech, everything was as quiet as that, if we had been contained in a room, you would have heard the proverbial pin drop. The women were seated on a huge mound of hay close by, and as usual, there were some who preferred to hear their own voices, so there were occasional cries of “hush” etc. from those who were desirous to hear what we knew was of the utmost importance to us.

The sisters at once took over the Hospital and from then on until they left Gwelo some months afterwards there was nothing but intense love and gratitude for them; they made no difference of sect; they were like Wesley in a way though instead of “all the world being their parish” all the sick were their patients. The order these dear women kept on the rough men in hospital was marvellous, if you must please remember that miners and others as a rule don’t belong to the class of Vere de Vere and are apt to make themselves heard, not agreeably sometimes.

One night about 12pm in the large ward containing nine patients there was a terrible uproar and cries of where’s the guard?” Before the guard could get there one of the Sisters appeared and quite quietly ordered every man to his bed. The order was obeyed at once. Then enquiries resulted in this: One man could not sleep so was allowed a night-light to read by, another complained that this light kept him awake and jumped up to put the light out. Sympathy was on the side of the sleepless man and the rest who were able, jumped up and went for the offender. (puts one in mind of a bolster fight) When this had been explained, the Sister went around to each one and the rest of the night passed quietly.

Another instance: I overheard one patient ask another to have something that the Doctor had forbidden and the answer was “I don’t care a damn for the Doctor, but I won’t do it because Sister asked me not to, and I would deny myself anything to please her.”

Among our number was an English MP and his son who had been on a hunting trip and were fortunate to have heard of the “rising” in good time to get into Gwelo. [Note 7] These, in the eyes of Gwelo, did not add lustre to their class, as they were anything but brilliant specimens. There was occasion for a speech on the unfurling of the Union Jack and we were all assembled to witness it. The MP then took the chance of saying some things which Punch would put as “things which one would rather have left unsaid.” He as much as told the women and children that they were fifty too many, that being their total number. His son was merely a Volunteer Trooper and told off for fatigue work in turn with the others; and when the oxen were being cut up for biltong he with others was put on for some hours. This was too much and it sickened him so terribly that three days in hospital was necessary to help him recover.

After a night in Gwelo Mr Rhodes and the contingent from Salisbury, and a good number of our men and all our best horses started for Maven’s kraal about eighteen miles north of Gwelo from which most of the murderers came. On arriving they found the kraal deserted and started to hunt around for the owners. One of the Volunteer Captains with his men came suddenly on a number of natives, when he turned on his men at once and said “we were not told what to do in a case like this; we must go back to the camp for instructions.” So off the men went, much against their wills. This is how the story was told on their return to the laager. However between the crowd they managed to shoot a few natives and then returned to Gwelo en route to Bulawayo. Between here and Shangani they found the telegraph line literally torn up’ poles (wooden ones) pulled up, cut in pieces and carried some miles away. This accounted for our being cut off in the way we were at the commencement of the laager.

The natives used to be afraid of the telegraph line and would not touch it in the last wars, saying the devil was in it. (when a thing is beyond their comprehension they always put it down to evil influence) But a telegraph line had recently been laid to Selukwe 25 miles SE and natives had been employed on it and had become accustomed to handling and using the materials, and thereby losing all fear of them.

The funerals during laager were many, not from wounds, but fever and dysentery, and were very sad. No attempt was made to fix coffins and the bodies were just sewn up in a coloured blanket, placed on straw on a covered Scotch cart drawn by four oxen. This was guarded by a number of Volunteers fully armed, and taken to the cemetery, about 1¼ miles from laager. The service was read by the Church of England clergyman, a volley fired over the grave and then the grave filled up and the march back. One woman said it was a disgrace to bury their dead in blankets when wood was available for coffins; and said if she died and was buried without one, she would do her best to haunt those who had the ordering of it. She was then told it was the proper way to bury a soldier. To this she would not agree saying; yes, if killed in action and no time for a proper burial” and I think she was right.[Note 8]

Life was very monotonous, a scare now and then at night caused by some piquet’s having accidently let off their guns, etc. and as all lights were ordered off at 9pm I can assure you it was anything but lively.

Gambling was carried to excess by the men and as cards were very scarce and no means of obtaining more, cards sold at £2 a pack. In fact, everything was painfully expensive.

I am sorry to say some of our officers were anything but capable and the wonder is how the men put up with their bullying in the way of orderly room punishments, pack drills, court martials, etc. as they did.

Things went on like this for about 5 months; with now and then about 40 men and officers going to the nearest kraals on patrols, but little or no good was done in this way, the natives returning to their fortresses in the koppies. About h this time Government sent a circular to all the families here telling them, if they would leave the country, they would have free passage to Mafikeng. This was done in view of the difficulty of transport, and as there were no more cattle left after the rinderpest, there was nothing to live on. Many families took advantage of this offer, but I heard that when one official went to one home, the mistress just took the paper and wrote an emphatic “No.” When asked the reason, her answer was; “I have undergone that journey too lately, having only arrived from the Colony two months before the rising and I don’t intend to try it again.” But this exodus was a very good thing as camp fever and typhoid were shoeing themselves. Not long after, the few of us who still possessed homes were allowed to sleep there, with stiff injunctions to make a rush for laager as soon as the alarm went. People began to leave by every convoy now and very soon there were only left sufficient men to garrison the place and a few families who intended making Gwelo their home.

Gradually we got back to civil life and customs and then came details of Mr Rhodes in the Matopos; I hear this from an eyewitness. When Mr Rhodes went to confer with the Chiefs, they were very dilatory about making terms, and our uncrowned king remained there for 3 weeks giving the Chiefs the same answers day after day, and never once showed impatience. So he conquered at last. The story goes of the witchdoctor, or Milemo [Mlimo] that he questions the trees and the air on any important event, and voices answer him. He is evidently a ventriloquist and a very clever one, and it by this supernatural power that he controls the tribes. At the beginning of the outbreak, rain was wanted badly, so he told the tribes to kill some white men; they did, and it rained, but not sufficiently, so they went to him again, kill some more white men, and they did it, and more rain came and so the story goes.

This is just New Year, and the police have arrived and their headquarters are to be Gwelo, with several forts in the district, so the military rule ends, and we once more take up the thread of our lives and place them in God’s hand, knowing that whatever He does is best.

On Xmas Eve 1896 there was another scare that the natives were massing two miles from us, and as they cover distance quickly, there was immediate danger. In the evening there were shots near the village, and a move was made to call us into laager. Laager now was the laager place, as all the fortifications were gone; danger being out of sight and only a few iron sheds round the one brick building. We were still under military sway, so bound to obey and were now assembled in one room; 9 women, 9 children and a few men to cheer the rest, the door and window being open as the night was very warm. There was not much … fear that I could see, but presently the civilian in charge of the Maxim found it filthy and jammed. Then the women made way and the deadly instrument was carried into the middle of the room and attended to. The only lights were two candles and a girl stood on either side of the Maxim holding these; the effect was a grand subject for an artist of strong powers. Then the cartridge belts were now filled for the Maxim, and another of the woman offered to do this. You will see by this incident that habit is second nature, and things that would frighten a novice, became only part of a tried woman’s existence.”

Incredibly, after the party of seventeen in laager at the Shangani Store had reached Gwelo on Friday 27th March and brought news of the killings around the Pongo Store and Eagle Mine and at Comploier’s Camp [Note 9] the Zeederberg coach was permitted to leave Gwelo on Saturday 28th March for Bulawayo. On arriving at Shangani Store, they found the naked body of a prospector named Wood, before pushing on to the Pongo Store without a mule change. Three miles beyond the Pongo Store, the mules came to an exhausted halt, and they were now under constant threat from Matabele warriors threatening them on both flanks. They were forced to abandon the coach and walk on foot, but were fortunately rescued by Colonel Napier’s column before darkness, when they would doubtless have been attacked.

NOTES

Note 1: the article in Rhodesiana No. 22 states the author of the diary was Peter Folk, but I think this is incorrect. His medals state P. Falk and an article on Rhodesian Jewry and its Story by Eric Rosenthal lists “Burger Peter Falk, (Gwelo Burgers, originally of Baden)”

Note 2: named Fort Gibbs, See the separate article on Fort Ingwenya.

Note 3: the Fort at Shangani no longer exists, but was on the summit of a hill at the 1893 Shangani battle site.

Note 4: This is T. Fitzpatrick listed on the Memorial and whose grave is at the small cemetery at Fort Ingwenya. See separate article on Fort Ingwenya.

Note 5 : This is probably Dr Thomas and Mrs Laura Langford who were killed on 25th March near Rixon’s Farm. They are listed in the article on the Fort Rixon Memorial.

Note 6: Peter Falk was a Burger as revealed on his British South Africa Company Medal 1890-97 and this must account for his comments.

Note 7: I think these must be Mr Egerton (MP for Knutsford) and his son on a hunting trip to the Sebakwe River who found safety at the Shangani Store on 25th March 1896 as described by F.C. Selous in Sunshine and Storm P95 and came into Gwelo on Friday 27th March.

Note 8: These would be the military victims listed on the Gweru Memorial, plus those from the 7th Hussars who are listed in the table, but not on the Gweru Memorial.

Note 9: Most of these victims are listed in the article on the Pongo Memorial.

Acknowledgements

The Gwelo laager, 1896. Rhodesiana No. 22 July 1970. P6-15. Note these notes are an extract from the hand-written diary of Peter Falk.

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia, 1890-1897. Rhodesiana, No. 12, September, 1965

C.K. Cooke. Memorials: Matabele Rebellion 1896. Rhodesiana No. 22 July 1970. P16-19

F.C. Selous. Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1968

G. van Tonder. Rolls of Honour 1896-1897