Fort Que Que (now Kwekwe)

- This little-known fort was built in September, or early October 1896, under the overall supervision of Lieut-Col. (later Lord) Baden-Powell and is still in good condition although some sections of the walls have collapsed.

- The name Que Que or Kwekwe is onomatopoeic and named after the sound of croaking frogs in the nearby river.

- The fort conforms to the then usual pattern in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) of being built in dry-stone walling, probably by local inhabitants under the supervision of the European military officers and having outside the walls, but under cover of the fort, a line of pole and dhaka huts which would house the garrison of about 25 men; comprised of one officer, a senior non-commissioned officer, six European troopers and seventeen African policemen. Wagons, mess huts, telegraphist and hospital were usually also outside the fort as it was never expected that the forts themselves would ever have to resist prolonged attack. The Battles of Shangani River (Bonko) and Bembezi (Egodade) had shown the amaNdebele the futility of trying to attack fixed positions and laagers protected by Maxim guns. [see the above articles in Matabeleland South]

- A fort represented a show of force, a stronghold only occupied as a last resort. As Peter Garlake states in his article, Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890 – 1897, that it is hard to imagine today the difficulties faced by the tiny population of new-comers separated by many kilometres of difficult, often hazardous country from their supply bases. They were confronted by an uncertain climate which resulted in flooded rivers cutting the roads for weeks at a time, horse sickness and rinderpest which decimated the horses and oxen, blackwater fever and malaria which caused many casualties amongst the men, and the uncertain reactions of the local population, many of whom were hostile.

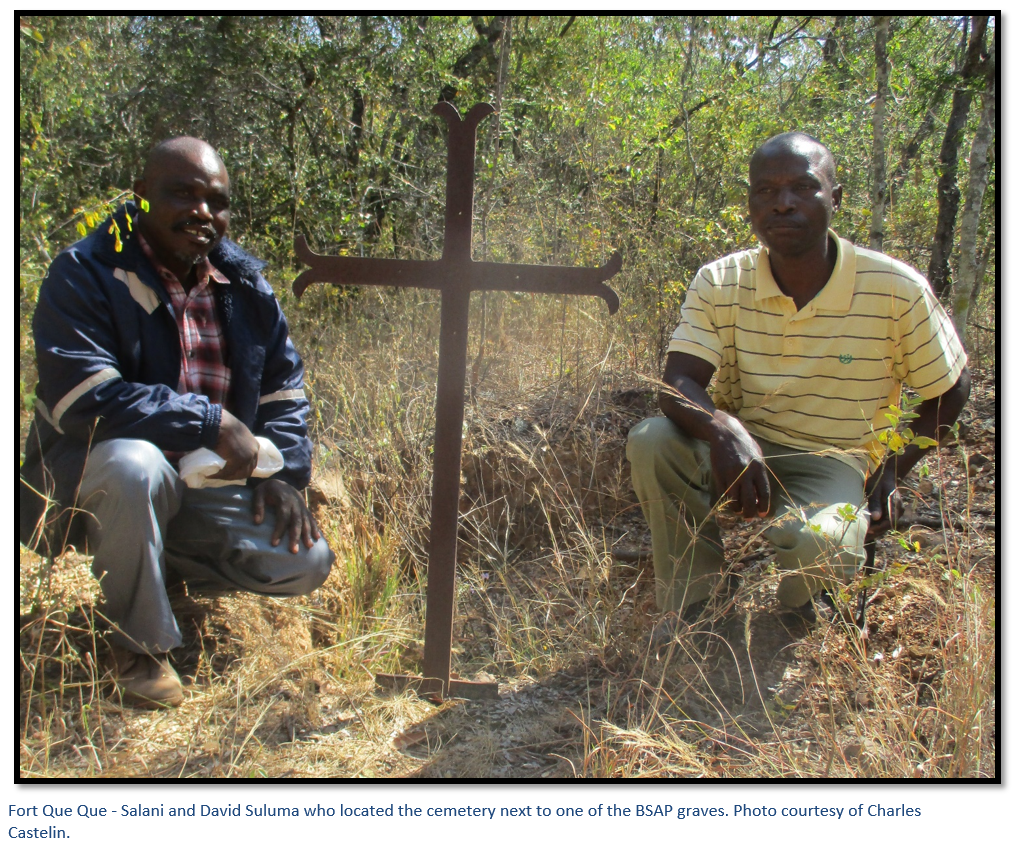

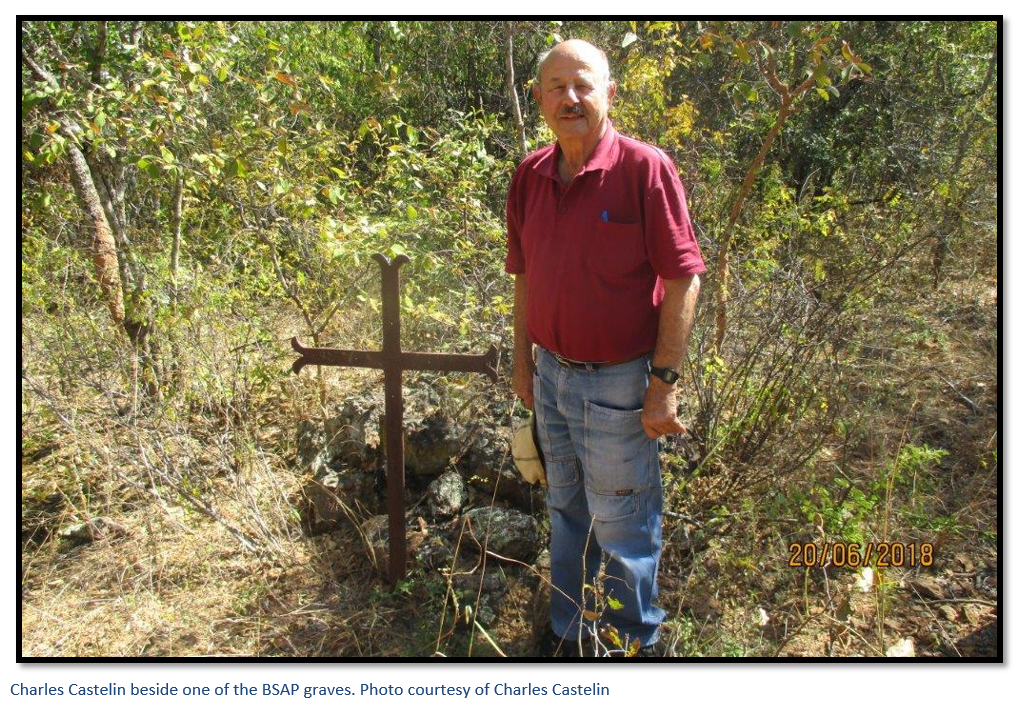

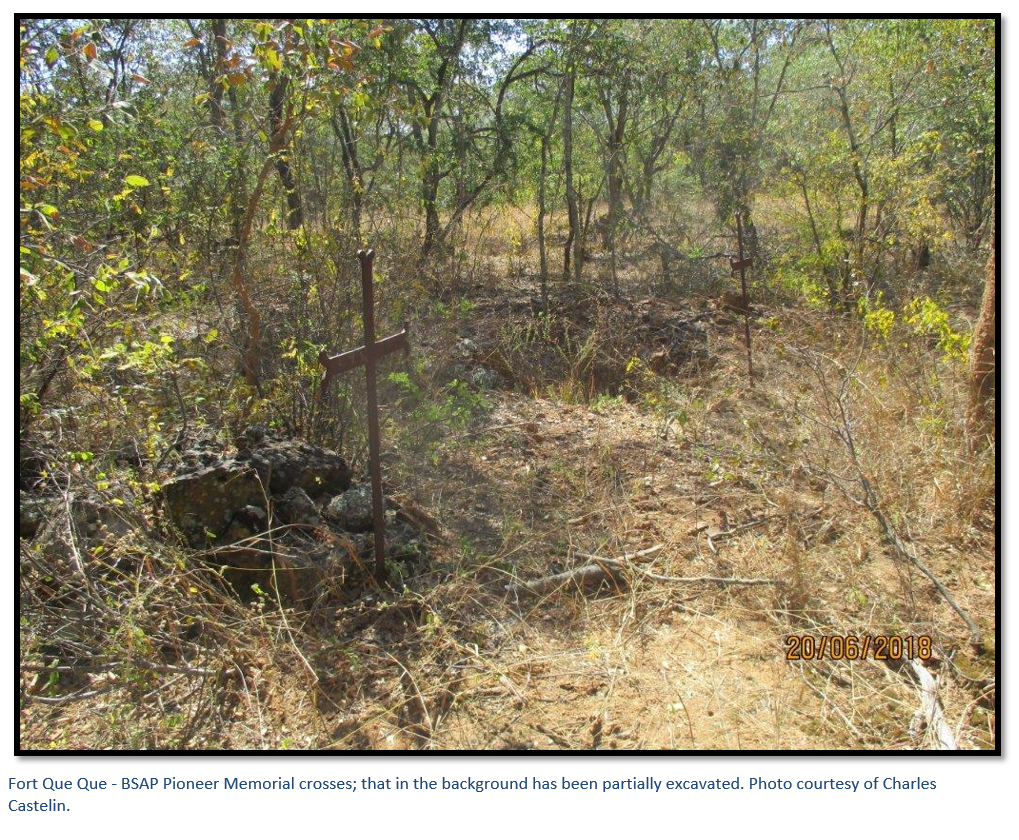

- The cemetery with the pre-1900 burials of a BSAP Sergeant and Trooper has now been found and photographs and details are given in the text.

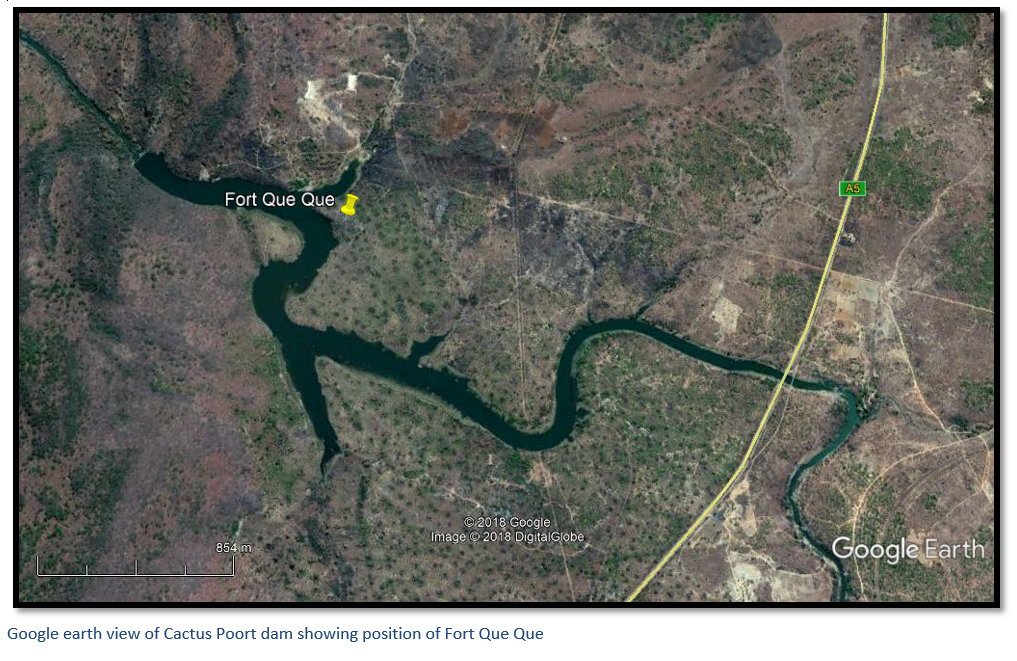

Follow the main Harare to Bulawayo national road (A5) through Kwekwe town towards Bulawayo and at 8.4 km turn right onto the Road to ZISCO. Travel 4.2 km and turn left onto Linksway Drive. Drive 440 metres and turn right onto Sally Mugabe Way. Continue along Sally Mugabe Way past the Engen Redcliff service station for a further 2.64 km, until 100 metres past the White House Guest Villa where the tarmac road ends. Continue down the gravel track bearing right towards the Cactus Poort Dam and Clubhouse; after one kilometre take the right-hand fork and travel a further three kilometres in a southerly and then south westerly direction around the base of the hill on the right. As soon as the easterly arm of the Cactus Poort dam is reached, park your vehicle, and follow the footpath in a southerly direction across the easterly extending bay of the dam and on the other side through the riverine forest and up the hill. The fort is at the highest point of the hill overlooking the dam to the west.

GPS reference for fort: 19° 03′ 09.37″S 29° 47′ 34.03″

Background

In late March 1896 many isolated prospectors and traders were killed in the vicinity of Maven’s kraal and Fort Ngwenya to the north of Gweru with their bodies lying unburied for six months until the arrival of the 7th Hussars under Lieut-Colonels Baden-Powell and Ridley in September 1896. By this time, the amaNdebele were streaming in to surrender their weapons – 180 surrendered in one day at Fort Vungu, but being in a poor defensive position, Fort Vungu was soon replaced by Fort Ngwenya in the west and Fort Que Que was built a further twenty-five kilometres to the north-east.

The fort only played a very peripheral part in the last stage of the First Umvukela, or Matabele rebellion of 1896. Gwelo (now Gweru) was the fort’s closest settlement and under the command of Captain Gibb who arrived from Salisbury (now Harare) in April 1896. A Gwelo resident recorded: “Captain Gibbs disgusted with state of laager, formed fatigue parties and commenced fixing us up, it’s a Godsend he came to camp.” It appears that due to the hostility encountered to the north of Gwelo, in the area then called Maven, transport and communication was primarily through Iron Mine hill, Umvuma (now Mvuma) Enkeldoorn (now Chivhu) and Charter to Salisbury (now Harare) and in May, Fort Gibbs, was built to guard this section of the road [see the Fort Gibbs article in Midlands Province]

At the end of 1896 the BSAP took over the running of Fort Gibbs until 1897 when it was abandoned, and it is very likely that the same process was repeated at Fort Que Que. However, in the case of Fort Que Que, the rapid growth of the civilian population at the Globe and Phoenix mine fourteen kilometres to the north also made its location as a police post redundant. Originally the mining settlement was named Sebakwe but renamed Que Que on 20 August 1902 after it was connected by rail to Salisbury and Gwelo in 1901 and to Bulawayo in 1902.

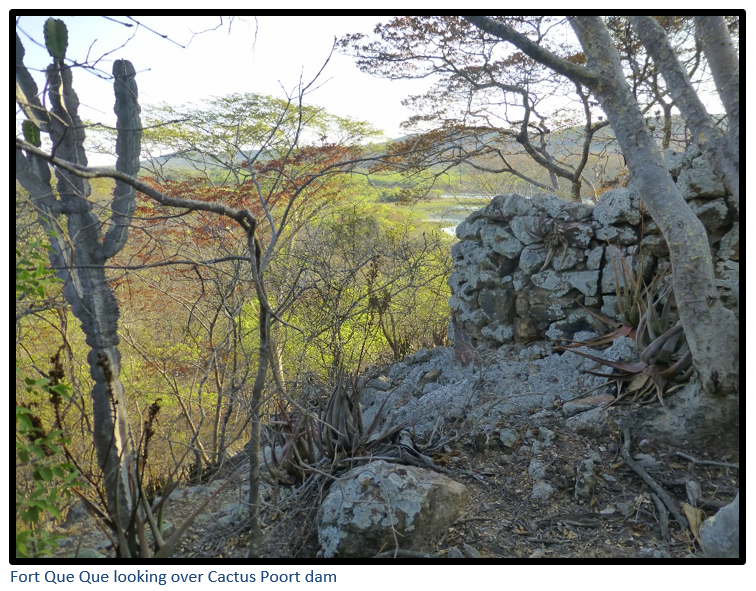

The fort is situated on the western end of a rocky hill overlooking the Kwekwe River and the present-day Cactus Poort dam is just one hundred meters to the west. The axis of the fort is east-west following the contour of the highest point of the hill. Very little is known about the fort, or for how long it was garrisoned by the British South Africa Police (BSAP) The fort was never proclaimed a national monument and Peter Garlake in his comprehensive article Pioneer Forts of Rhodesia 1890 – 1897 makes only one mention of the fort.

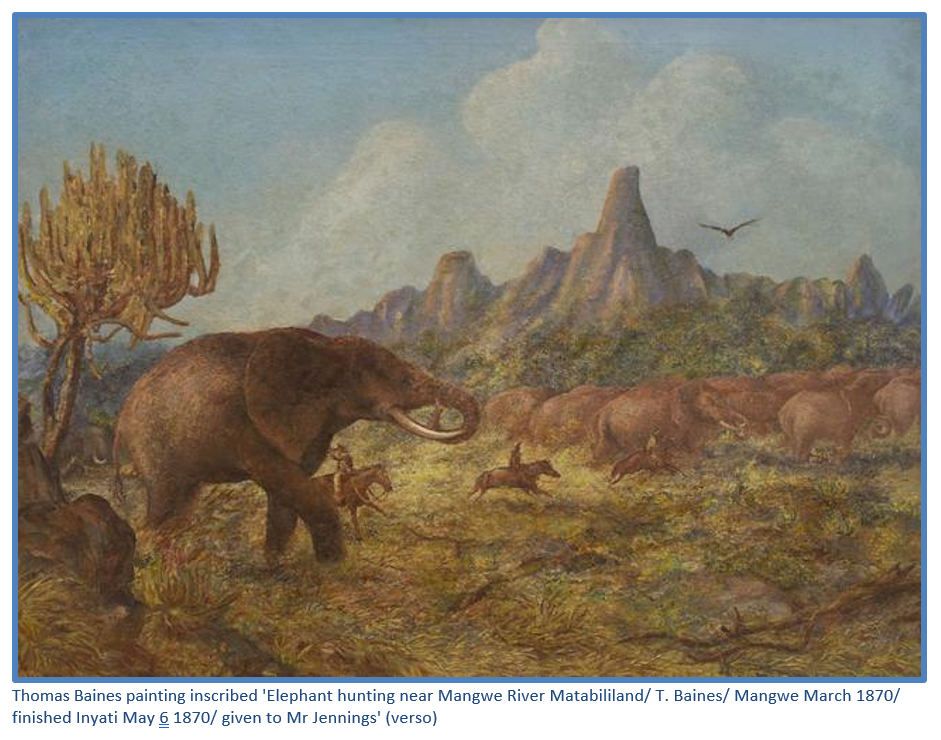

The crossing point at the Kwekwe River, about 600 metres south-east of the fort at a place which is now submerged under the Cactus Poort Dam where they were always assured of water, was a well-known trek stop for the early travellers and hunters following the Hunter’s Road that had been cut by Thomas Baines in 1869. At this point the Kwekwe River has forced a narrow passage through the banded iron-formation (previously known as banded ironstone) range; the river was subsequently dammed in 1944 to supply water to the Redcliff Works of the Zimbabwe Iron and Steel Commission (Subsequently de-nationalised to become RISCO and then re-named ZISCO) that was founded in 1942 (nationalising the assets of the Rhodesian Iron and Steel Corporation) in the then Southern Rhodesia. At its peak ZISCO was Africa’s largest integrated steel works north of the Limpopo and south of Egypt with a capacity production of one million tonnes of liquid steel annually and employing some 6,000 people.

Below Fort Que Que the Hunter’s Road crossed the Kwekwe river and then continued to the north-east on its route to its ultimate destination at Hartley Hills. The actual location of the crossing point and the tell-tale cut through the river banks is most likely now hidden below the Cactus Poort dam, but it would make an interesting afternoon’s walk to look for signs of the Hunter’s Road which probably still exists as a footpath, or track heading in a generally north-east direction.

Structure of the Fort

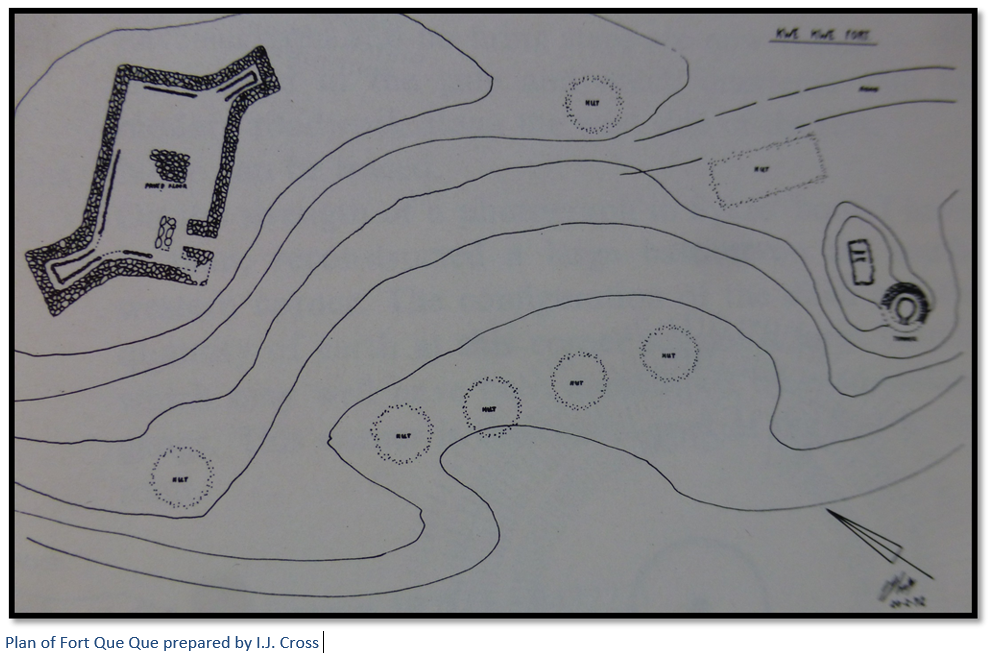

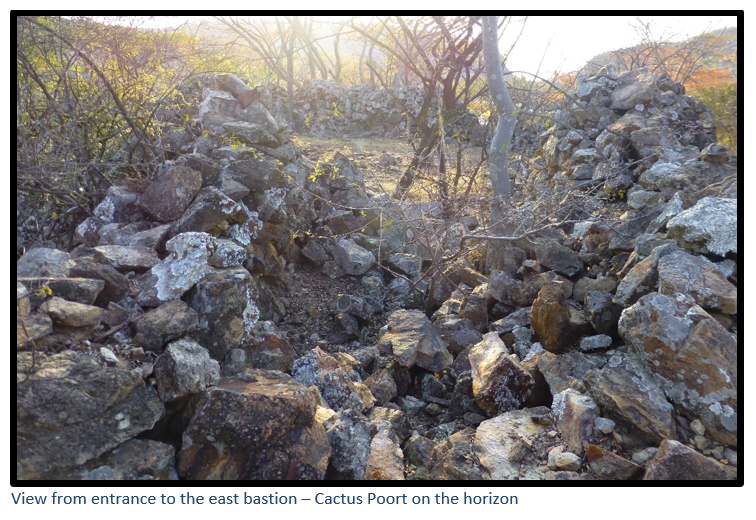

The shape of the main fort is rectangular with two projecting corner bastions facing east and west. Peter Garlake says the first fort to feature this new design of rectangular gun emplacements projecting from diagonally opposite corners was Fort Usher No 3, designed by Baden-Powell in July 1896 and copied at Fort Que Que. Garlake quotes Major Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boy Scouts who campaigned in Matabeleland in 1896 – 1897 as describing the forts by saying: “They would make a sapper snort but were none the less effective for all that. They are first, the natural kopje or pile of rocks aided by art in the way of sandbag parapets and thorn bush abattis fences – easily prepared and easily held.”

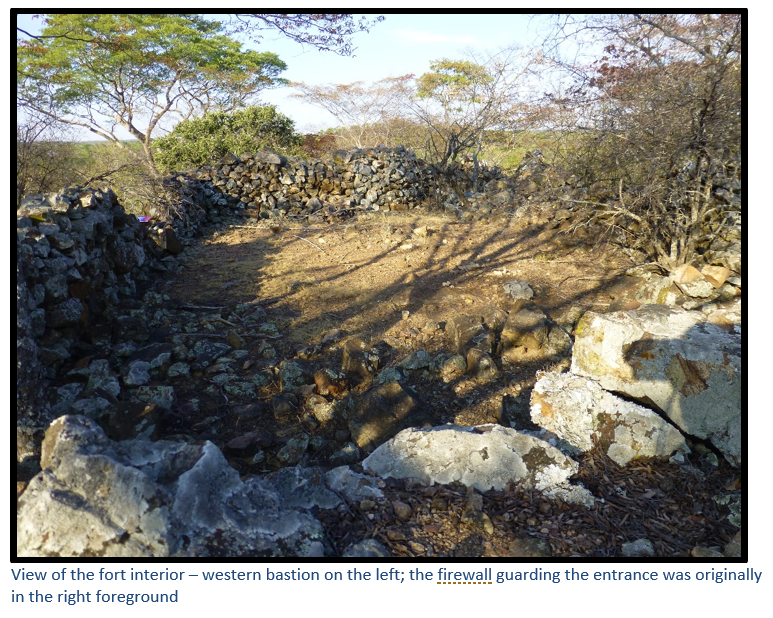

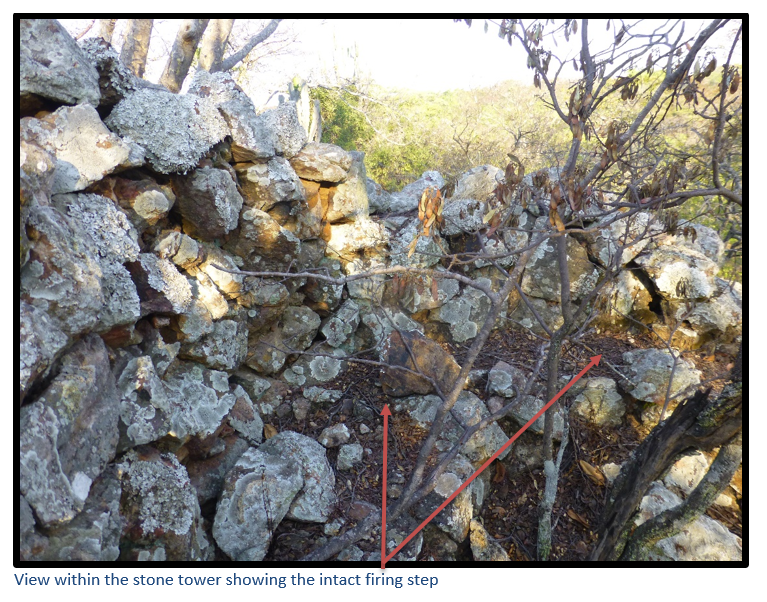

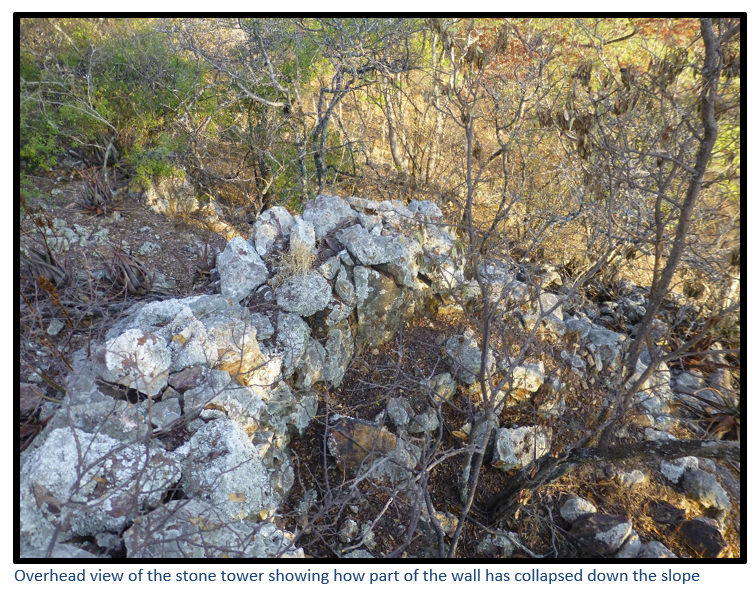

I.J. Cross in his article Rebellion Forts in Matabeleland says the rough stone walls of the main fort were in fair condition in 1972, although much of the wall at the south corner had collapsed and been piled up against the entrance to the western bastion and most of the stone from the fire-wall blocking the gate on the south had been removed. The fort’s condition appears to be much the same today with little further damage. There are still traces of the 60 cm wide fire-step around the walls, and in the centre of the fort, a stone platform which was the foundation for a single corrugated-iron hut where ammunition, spare rifles and saddles would be stored.

There is no ditch, perhaps because of the rocky nature of the terrain and its elevated position, and because the fort’s designers cut down the surrounding woodland to give the defenders a wide field of fire.

The ground slopes downhill from the fort on all sides except the south, where an uneven plateau exists, until the hill drops steeply to the south and the Kwekwe River. A round stone tower, with a firing step and drain on the ground has been built on a small rise to cover the dead ground south of the fort. Some of the stonework had collapsed by 1972, but large sections of the still surviving walls indicate that the dry-stone walls were well-dressed and neatly finished off and about two metres high with a fire-step around the interior. The superior finish of the stone tower to the main fort may have been necessary because the steep drop-off needs a more compact shape supported by a solid foundation to prevent the walls from collapsing.

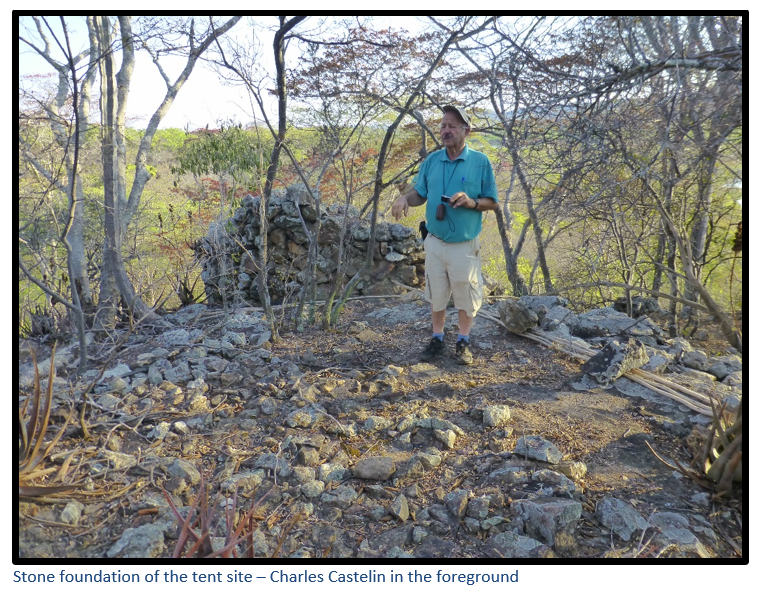

The scattered dhaka remains of seven huts extend across the small plateau; the stone foundations of a tent site (so-called because no dhaka remains were spotted here) near the round tower can be seen and the track to the fort can be traced following the contour of the hill north of the tower. The tent site is the largest non-military structure and may have been the site of the administration office. My colleague, Charles Castelin, found a farrier’s tool illustrated below in the hut base nearest the main fort.

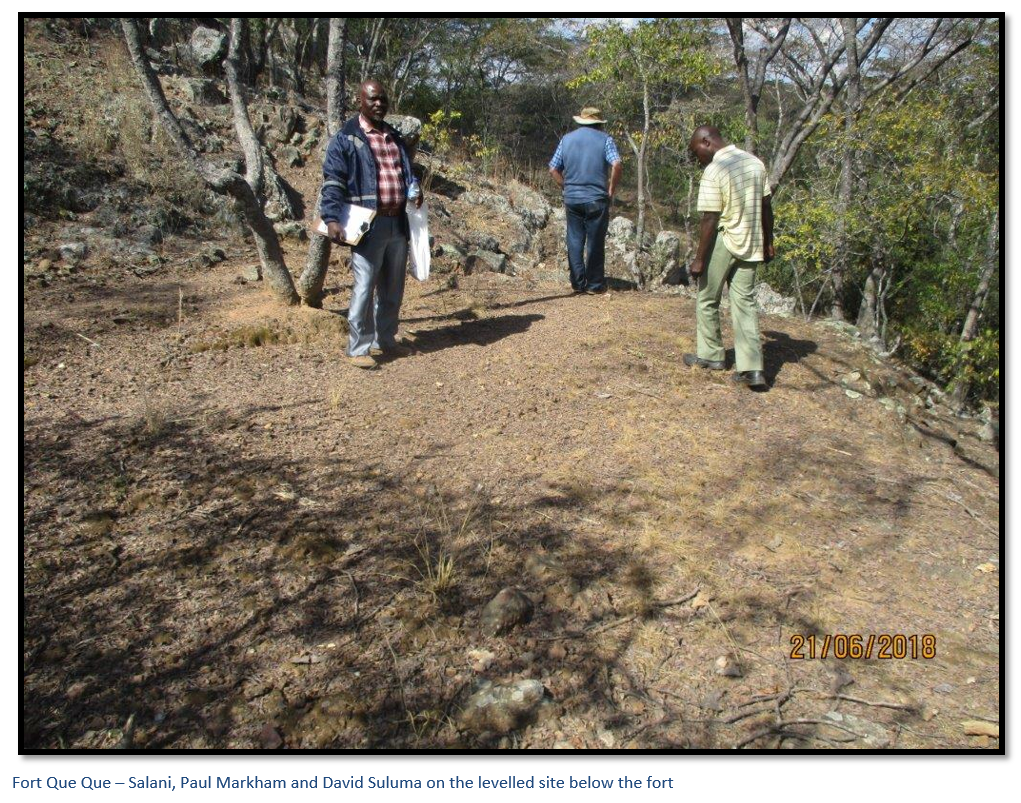

Below the fort on the slope facing the Cactus Poort Dam is a levelled site some 7 metres by 7 metres which has dhaka foundation remains and which may have contained another hut.

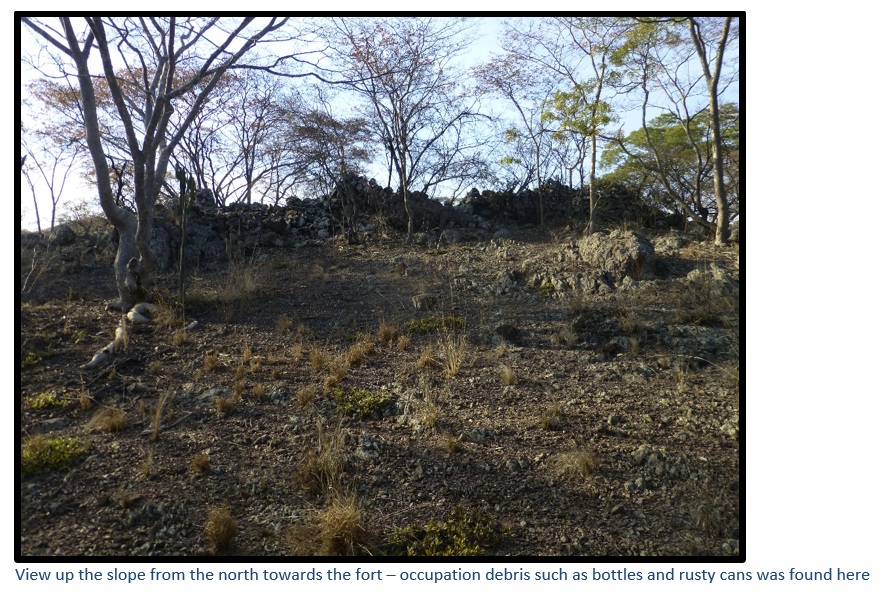

Occupation debris

Conditions at the various BSAP forts varied considerably. For instance, Fort Umlugulu in the Matobo, or Matopos Hills received four Bulawayo newspapers daily and tobacco, jam and groceries were stocked for sale to the troopers. No liquors or beer were allowed at any of the forts, but from the number of broken whisky bottles on the northern slope of the hill, this rule appears to have been ignored at Fort Que Que. Few complete bottles survive, as empties were invariably used as shooting targets, but there is scattered thick green and black glass. A considerable amount of occupation debris survives on the slope to the north and the south of Fort Que Que consisting of the remains of ration tins and broken glass. A tin still marked Crosse & Blackwell, London, indicates that the troopers bought sauces and tinned foods to supplement their basic rations.

From the quantity of occupation debris found around the site no attempt appears to have been made to bury any of the rubbish – a great windfall for visitors one hundred and twenty years later!

A telephone connection between the BSAP at Fort Que Que and Gwelo after 1897 was one of the first telephone lines in the country. Made of No 14-gauge baling wire; reception was said to be poor! Presumably the telephone line followed the track from Gwelo (now Gweru) so any breaks could be easily repaired.

Stone age artefacts

The site above and close to the Kwekwe River would have made an ideal stone age camp site and several discarded points, blades and scrapers were seen lying on the ground. They were made from various stone types including quartz, flint, obsidian and chalcedony which may have been collected from the nearby Kwekwe riverbed. Most Stone Age tools were fashioned through “knapping,” the process of flaking off small pieces of stone from a larger one.

The Cemetery

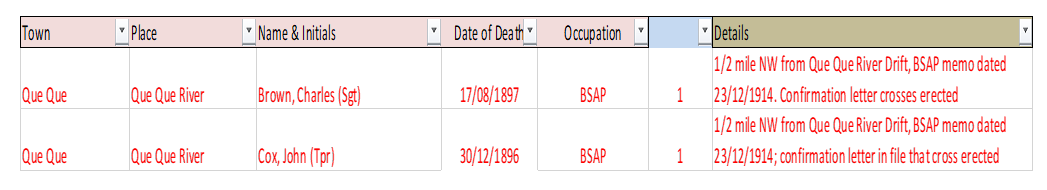

In researching a recent article on the role of the Loyal Women’s Guild in 1909 – 1910, I came upon a letter from the BSAP Supervisor at Gwelo dated 23 December 1914 to the Assistant Commissioner in Salisbury stating: There are two isolated graves in the bush near Que Que old Police Camp. One has a broken iron cross on it with “Sergt. Charles Brown B.S.A.P. Aug 17th, 1897” inscribed. The other has nothing on it and is I believe that of a trooper of Corporal John Cox who was drowned crossing the Que Que river in 1899. I recollect this occurrence vaguely. Have you any particulars in the old records? A cross might be erected; Is there not a fund for this purpose?

My own research into pre-1900 graves indicate the following were buried in the nearby cemetery:

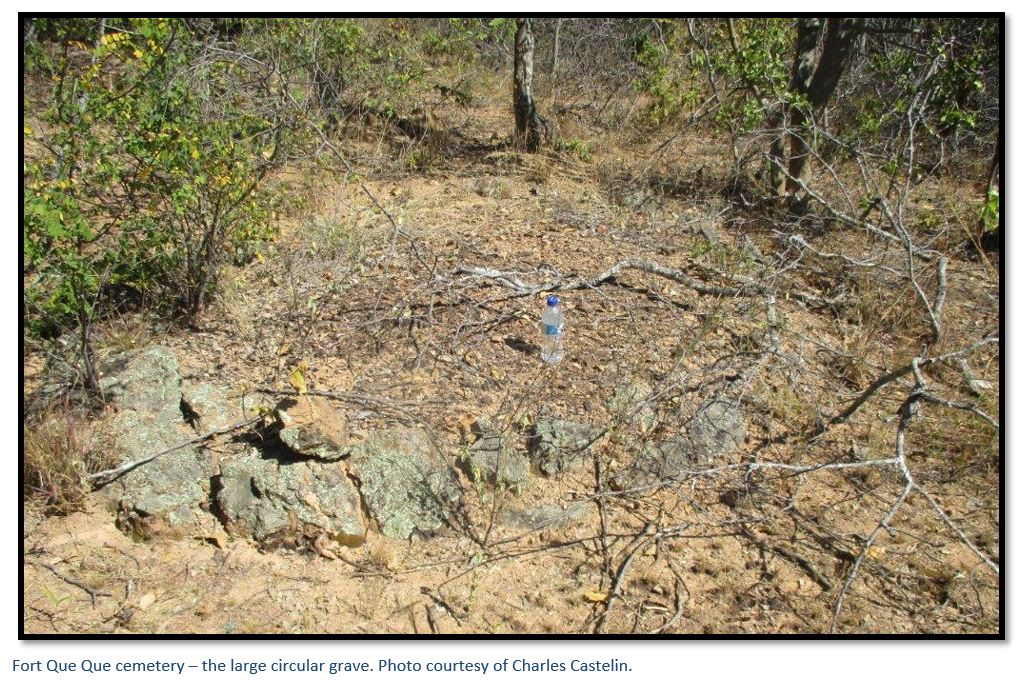

In June 2017 at the request of Charles Castelin, Chris Machona asked two colleagues to search for the cemetery; they were successful in their search and subsequently guided Charles Castelin and Paul Markham to the site. In a short period the team of four located twenty-two graves sites ranging from a child’s grave to a large circular grave with a radius of three metres and a large oblong grave. Two had the Pioneer Memorial crosses erected by the Loyal Women’s Guild in 1909-10 (see the article on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) and originally would have had the details referred to above.

Both of the brass plaques on the Pioneer Memorial Crosses had been removed so the team were unable to identify the individual graves and one of the graves had been partially excavated.

British South Africa Police – the men who occupied Fort Que between 1896 – 1897

I have been unable to find any accounts by BSAP Officers or Troopers of life at this remote outpost before 1900. However, Sir Godfrey Huggins, the longest serving Prime Minister of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) from 1933 – 1953, said in his forward to the book Blue and Old Gold – Stories of the Rhodesian Police, that he had been associated with the force as a surgeon since 1911 when he sailed from England to Cape Town with eleven new recruits for the BSAP.

Most recruits came from England, driven by a sense of adventure to join a unique Police force that gave both civil and military functions to the country. When they retired, many stayed on in Rhodesia and went on to become leading personalities in industry, commerce, mining and farming. Sir Godfrey said that the BSAP, together with the nursing services, were the major source of citizens to then Rhodesia. From the earliest days, BSAP outposts in the outlying areas of the country, such as Fort Que Que, constituted the sole representatives of law and order and of Government.

James Appleby, BSAP Commissioner 1950 – 1954 in the Introduction to Blue and Old Gold said that every European recruit started as a trooper and needed to work their way up the junior ranks. By carrying out long patrols visiting kraals and villages in the remote areas by horse, mule and bicycle they developed a close friendship and knowledge of their African constable colleagues and a deeper understanding of African customary law and traditions.

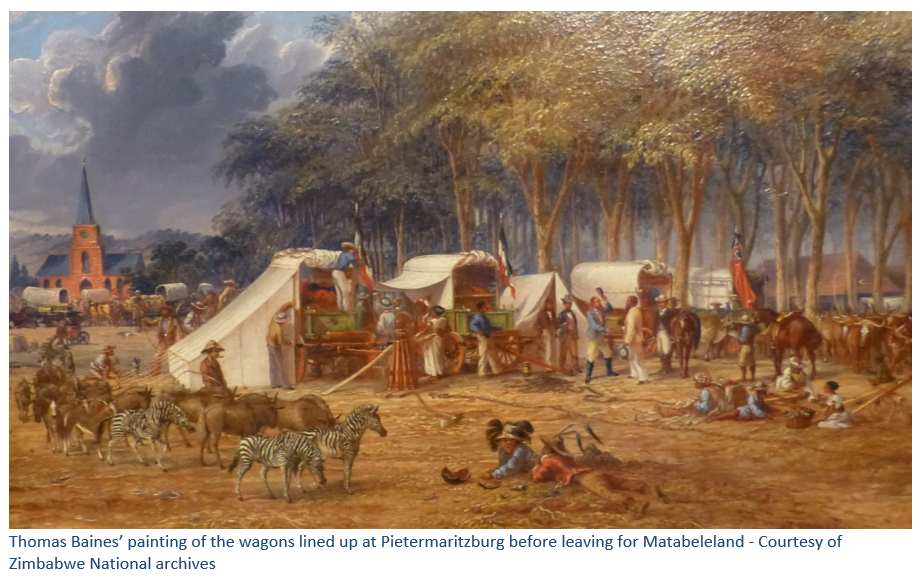

A shortened account from Thomas Baines’ book The Gold Regions of South Eastern Africa.

In Thomas Baines’ book The Gold regions of South Eastern Africa he tells how several prominent Natal citizens formed The South African Gold Fields Exploration Company and appointed him in command of the expedition to the north, with C.J. Nelson as mineralogist and R.J. Jewell as company secretary. [See also the articles on Hartley Hill in Mashonaland West] Baines arrived at Durban by sea from England in February 1869 and on 13 March their expedition left Pietermaritsburg in company with their German friends Edwin Mohr and Adolph Hubner.

After an uneventful journey Baines’ party reached the Tati River in north-east Botswana at the goldfields below Francistown where they out-spanned near the store of the London and Limpopo Mining Company under the leadership of Sir John Swinburne, Bart. Soon afterwards they reached the Mangwe River where their companion, the hunter Henry Hartley, introduced them to John Lee. John Lee had received Mzilikazi’s permission to hunt in Matabeleland in the 1860’s and in time became a confidante and friend of Mzilikazi. He was granted a large area of land and in return became Mzilikazi’s and then Lobengula’s agent in their business dealings with early European travellers. Everyone stayed with John Lee until permission was granted by the King to enter Matabeleland.

Mzilikazi had died in September 1868; the succession of Lobengula was not accepted by Mangwane, one of Mzilikazi’s older sons and some of the izinduna (chiefs), and Lobengula’s coronation only took place at Mhlanhlandlela, one of the principal military towns in 1870 after a period of serious civil war.

Baines party had arrived in the interregnum and Lee went with Baines to Manyama’s kraal; where they showed Manyama their letter of introduction from the Governor of Natal and Lee explained the general purpose of the visit. Special messengers were sent to the council of the nation and after two weeks they were received by two induna messengers who attempted to question Baines, but Lee told them the letter’s contents were for the personal attention of Um Nombata, Mzilikazi’s chief Councillor.

After receiving permission to enter Matabeleland they drove the ox-wagons as far as their exhausted oxen would go; Baines then left Jewell and Watson under the protection of Lobengula whilst Nelson, Lee and he went ahead to Umbeko’s kraal, where they were told that only the Regent Um Nombata could consider their application. At Emampanjene they met the old chief sitting naked by the door of his hut and after a friendly welcome they were escorted to the kotla, or council place where Baines requested permission to travel and explore for gold and for protection. He added that if gold was found, Um Nombata could then make laws to regulate the conduct of those that followed. After discussion, Um Nombata agreed to Baines’ requests providing he returned and reported his findings.

Whilst Baines waited for Lee to send him a fresh span of oxen, he received a letter from the other induna’s saying Um Nombata was an “imbecile” and his authority to travel was not valid because they had given Sir John Swinburne and the London and Limpopo Mining Company exclusive gold prospecting rights. Baines rode over to Inyati Mission where he met the Reverends’ Thomas and Sykes and representatives of the dissenting induna’s but told them he considered Um Nobata’s permission exceeded theirs.

Nelson found several gold-bearing quartz reefs near Um Nombata’s kraal and further alluvial gold in the Shangani River; on 6 August 1869 after striking across country with one ox-waggon, Nelson and Baines reached the Hunter’s Road and met Samuel Edwards, who was returning from Sir John Swinburne’s party ahead of them, to fetch supplies. Travelling east and then north (Baines was a meticulous record keeper of distances, directions and altitude) they crossed the Vungu, Gwelo and Ngwenya Rivers before crossing the Kwekwe (which Baines calls the Quaequae River) near which they found numerous gold bearing quartz reefs.

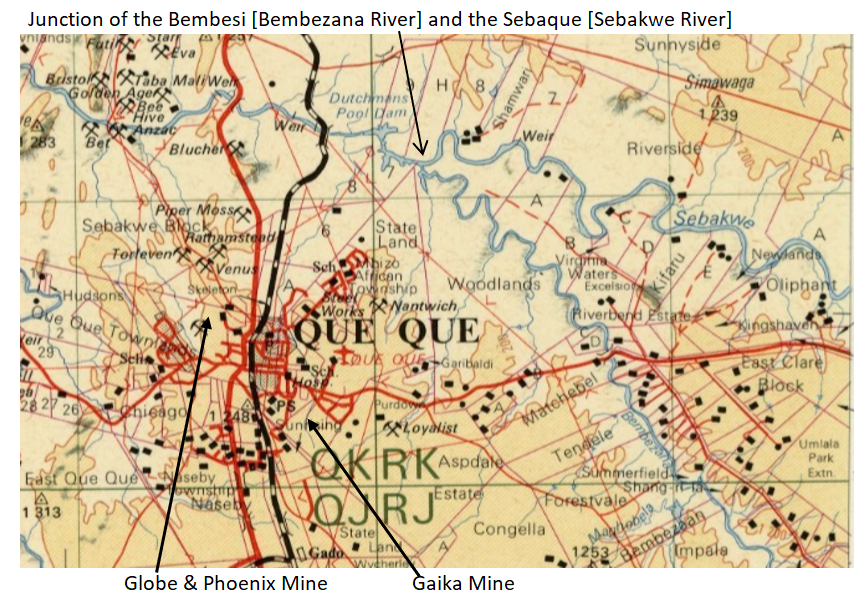

Baines writes: “The country was park-like and beautiful; the graceful matchabela which in its young leaf presents a rich yet delicate crimson tint, changing by various gradations into green, as its foliage is matured; the leghoudi, which buds forth in golden yellow, and the mimosas, acacias, aloes, and occasional euphorbias added an ever-varying charm to the scene; while the higher lands were adorned with large white flowering proteas, and other plants suited to their altitude. We crossed the Bembesi [Bembezana River] and the Sebaque [Sebakwe River] near the junction of which eight or nine miles further north many apparently rich quartz reefs exist, which were subsequently visited by Mr Nelson and myself. Mr Nelson tried the river and found a trace of gold, and I remarked galena in several specimens of the quartz.”

The quartz reefs to which Baines refers were perhaps the Globe and Phoenix and Gaika deposits almost thirteen kilometres (8-9 miles) south of the confluence of the Sebakwe and Bembezana Rivers.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Charles Castelin for guiding me to Fort Que Que and making corrections to the text and Ben and Frieda van Rensberg of Redcliff for their generous overnight hospitality. Also to Chris Machona and Salani and David Suluma who located the cemetery at Fort Que Que

References

I.J. Cross. Rebellion Forts in Matabeleland. Rhodesiana No 27 December 1972

P. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890 – 1897. Rhodesiana No 12 September 1965 P37 – 62.

T. Baines. The Gold Regions of South Eastern Africa. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1968

Blue and Old Gold – Stories of the Rhodesian Police. Howard Timmins, Cape Town 1953