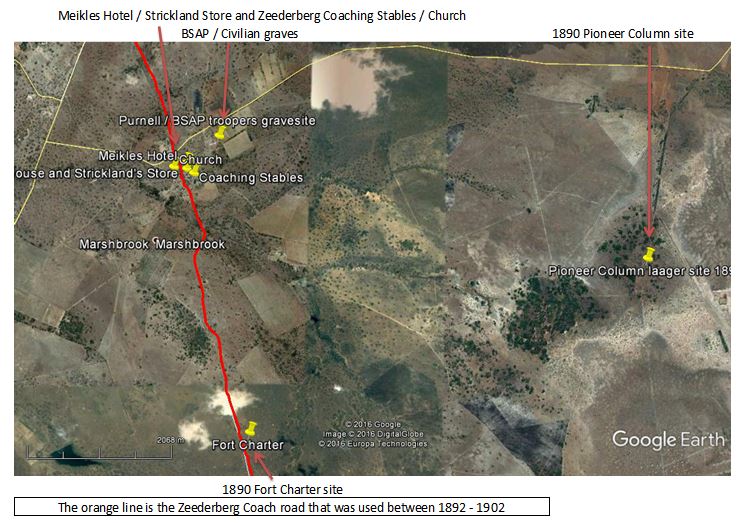

A description of the old Meikles Hotel, the Mill and Coach House and Coaching Stables and Strickland’s Store on Marshbrook Farm (now Charter Estates) in Charter District (PART 1)

The Mill and Coach House and Coaching Stables, the Meikles Hotel and Strickland’s Store on Marshbrook (now Charter Estates) date from 1892 – 1894 and are amongst the oldest surviving buildings in Zimbabwe. They predate the Market Hall, Harare’s oldest surviving building which was built in 1903 and therefore deserve recognition and preservation.

They are amongst the few early buildings in Zimbabwe which remain intact; only the Coaching Stables where the Zeederberg’s mules were kept has been significantly altered into a tobacco barn and even here the original structure can still be seen.

It is quite surprising how little is known about these buildings; even the date of their construction is obscure. There are very few written accounts; although many visitors pre 1902 spent the night at the Meikles Hotel…perhaps they were too exhausted from spending days tightly packed into a Zeederberg Coach to make observations. However in later years, David Worthington, Manager of Charter Estates for 37 years, comments that they had many distinguished guests who came for extended stays over Christmas.

Charter Estates enjoyed a high reputation for the quality of its cattle herd which was built up over the years by David Worthington from 1948 – 1985 and Tony Mirams from 1985 to 2000.

The current buildings usage seems to mirror the confusion and chaos brought about by the 2000 land invasions as they are each used by different parties: the Hotel by Sadzaguru, the Coaching Stables by Dr Muchena, the Mill by various parties and Strickland’s Store by someone else; nobody is responsible for maintenance, and the buildings which should be listed as National Monuments, will fall into increasing disrepair.

Distances are from the Mupfure River (formerly Umfuli River) just south of Beatrice on the A4 National road going from Harare to Chivhu (formerly Enkeldoorn) At 28.6 KM take the gravel road to the left at a large “Sadzaguru” signpost. The GPS reference is 18⁰30′44.39″S 30⁰53′05.74″E Keep to this road which is in good condition. At 41.8 KM cross a spruit and turn left in front of the farmhouse, 48.8 KM reach a T junction and turn right, 49.2 KM turn left onto a gravel road marked to Marondera and Charter Primary School, 50.9 KM turn right at the signpost “Sadzaguru” onto the farm entrance road (formerly Charter Estates) 51.2 KM pass Church on right.

For the return journey retrace the same route as the quickest way to get back to the A4.

Meikles Hotel and Bar: 18⁰33′27.11″S 31⁰03′12.73″E

Mill and Coach House and Strickland’s Store: 18⁰33′30.12″S 31⁰03′13.34″E

Coaching Stables: 18⁰33′32.00″S 31⁰03′17.64″E

GPS reference for Civilian and BSAP graves: 18⁰33′13.94″S 31⁰03′30.35″E

Introduction

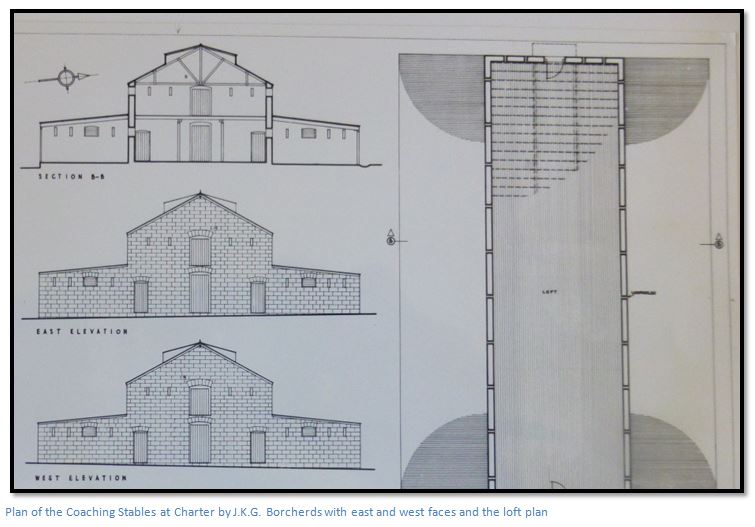

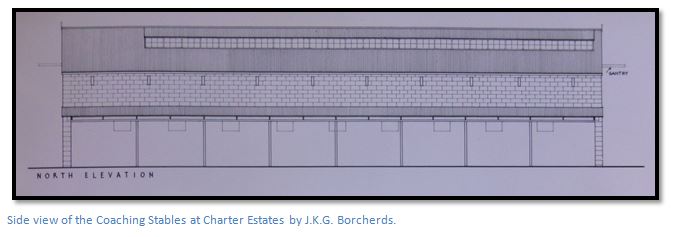

This article relies on a survey carried out by J.K.G. Borcherds, B.Arch., RIBA in September 1960 in which he drew the architectural sketches below and made some preliminary explanations on Fort Charter and other buildings on Marshbrook Farm; the paper and sketches were filed in the National Archives. Thanks to Tony Mirams, who was Manager of Charter Estates for fifteen years and lent me his personal papers, and to his son Craig, who guided me around on a first visit. Thanks also, to Mr Eustace Kagande Wachiseka of Sadzaguru who showed me around the Meikles Hotel, and to Mr Harold Mhundwa who guided me through the Coaching Stables.

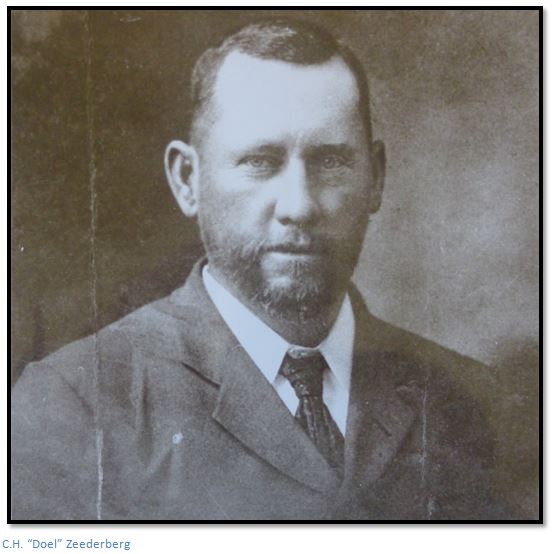

Zeederberg Coaching Services

The first firm of "Zeederberg & Co., Coach Proprietors" was run by the four Zeederberg brothers in Pretoria, and was at first a purely South African concern with their first route from Pretoria to the Northern Transvaal, in 1890. It was the occupation of Mashonaland, his friendship with Cecil Rhodes, and the urgent demand for transport north of the Limpopo, which caused Christian Hendrik “Doel” Zeederberg to set up in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) The rainy season of 1890 was extremely heavy with over 60 inches (152cm) of rainfall at Salisbury (now Harare) From December to 1890 to February 1891 Mashonaland was cut off from the outside world and there was no transport from Fort Tuli with ox-wagons bogged down in the black vleis, or held up on the banks of the flooded rivers, such as the Umzingwani and Nuanetsi, where without proper shelter, food and medicines, many young men, acting as mounted BSAP despatch riders to carry the mail, died of malaria…two are buried on Charter Estates.

The local Zeederberg partners were C.H. “Doel” Zeederberg and H.J. Zeederberg and they played a major role in opening up transport services in early Rhodesia with their service commencing in 1891 with a passenger coaching and mail service from Fort Tuli to Salisbury, over 500 kilometres, which cost the BSA Company £4,500 annually. The service was soon extended to Pretoria / Pietersburg, via a pontoon built over the Limpopo River at Pont Drift, eight kilometres upstream from Rhodes Drift. This service continued until 1902 and the 1893 yearbook "Guide to Southern Africa" gives the fare from Tuli to Salisbury as £15 with the journey taking 14 days!

The following description appeared in 1894: “In fine weather, when the roads are in good condition, a coach journey may be very enjoyable, but in bad weather capsizes are unpleasantly frequent and occasionally a coach with its freight and passengers will stick in the mud for many hours. Teams are changed every ten or fifteen miles, and some idea may be inferred of the number of horses and mules kept at the different stations from the fact that frequently four or five coaches will require fresh teams at one place during the day. The rate of traveling, including stoppages, is not much more than six mph. Fares are high, ranging from 9d. to 1/- per mile. The allowance of luggage per passenger ranges from 25 to 40 lb., and every additional pound weight is charged 6d. to 1/6d. extra according to the distance travelled, whilst, if the mail should happen to be heavy, luggage is frequently shut out."

In 1896 a severe rinderpest epidemic killed most of the trek oxen upon which the country relied for transport of foodstuffs, and during the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela, the Zeederberg coaches were the only transport between Bulawayo and the outlying settlements, going as far as Pietersburg, via Gwanda, for supplies and ammunition.

The construction of the railway line for the Beira and Mashonaland and Rhodesia Railways had begun from Fontesvilla, 56km inland from Beira, to Umtali (Mutare) in September 1892, and from Vryburg in the Cape Province to Bulawayo in May 1893. The Bulawayo line was completed in October 1897 and the Mutare line in February 1898. The link between Salisbury (Harare) and Bulawayo was finally completed in October 1902, after initial construction was brought to a halt by the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War in October 1899.

After 1902 Zeederberg's coaching services was discontinued on the major transport routes, but they still conveyed passengers from railway stations to the growing settlements around gold mines, such as Mazowe, Bindura and Shamva. During the Boer War, Zeederberg’s mail transport contracts were suspended and its resources put at the disposal of the British Government. The New Zealand and Australian forces with all their equipment was transported from the railhead at Marandellas to Bulawayo to assist at the relief of Mafeking. Officers went by coach; other ranks having to be content to travel by ox-wagon, a much slower mode of transport taking up to twenty-five days from Marandellas (now Marondera) to Bulawayo.

Charter Estates

Early Days

A number of Pioneer grant farms were taken up in the district, mostly for land speculation, but those that tried farming soon found the lack of a suitable market made it unprofitable and sold to go gold mining, or left the country, but a number of Afrikaner families did settle in the district.

John Meikle and David Worthington tell us that the Meikles brothers purchased Marshbrook Farm in 1892 to build a Hotel and Store to be run by their brother-in-law, Arthur Strickland. However, it appears they built their Hotel on the wrong farm, on Claricedale, and had to buy this farm as well. This legend could well be true, as on the 1:250,000 map the farm boundary does appear to run between the houses. Over the next six years, the Meikles Brothers bought 26 farm properties; one of them for six blankets and a single-furrow plough; Moorland Farm of 16,000 acres for £3/19/6, and another for an ox-wagon with a grand piano, but without oxen, possibly due to the rinderpest in 1896.

Charter Estates, now comprising 99,000 acres in one block, plus another 3,500 acres a few miles away, became Stuart Meikle’s property and on his death was inherited by Cyril and Jack Meikle, but Cyril died very young from appendicitis, leaving Jack as sole owner. Charter Estates was known for its cattle, sold as draught oxen. Jack was a keen ornithologist; hence his Shona nickname “Masiri” with a reputation as a kind soul and good host.

However, after the farming difficulties during the Great depression, Jack Meikle sold Charter Estates in 1938 for £20,000 the cattle were included in the price, to Herman Struckel, an Austrian / Italian immigrant who made his money making bricks in Durban and who made quite a farming success growing maize using tractors, despite the difficulties of the war years, and also continued the cattle tradition.

Post Meikle era from 1939

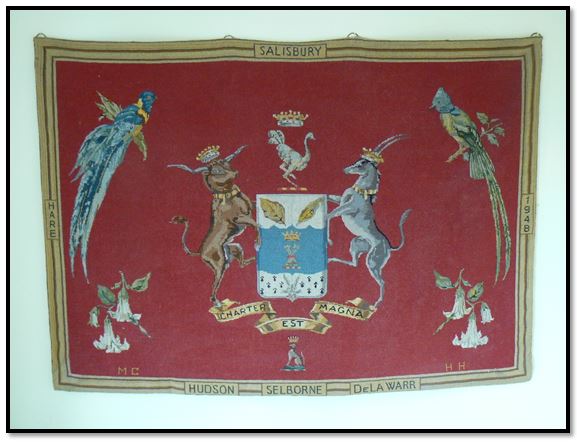

In 1946 Charter Estates was bought by a group of five prominent Conservative Members of the House of Lords and Commons. They were Rob Hudson, later Viscount Hudson, who as Minister of Agriculture had a big role in the war effort; Lord De La Warr, who became a Cabinet minister in Macmillan’s government; Mr Hare, who was Minister of Labour and then Agriculture under Prime Minister Anthony Eden, later Lord Blackenham; Roundell Cecil Palmer, third Earl of Selborne; Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 5th Marquess of Salisbury,

and finally Sir Ellis Robins who became Chairman of Charter Estates. Since 1935 there had been a plan to run a railway line from Umvuma (now Mvuma) along the watershed and through Charter Estates to join the existing railway line at Bromley, and this may have been an added incentive to purchase Charter Estates.

David Worthington was recruited in 1948 and built up a good Afrikaner, Hereford and Sussex herd which at its peak comprised 11,500 head of cattle and over 4,000 breeding cows; many farmers bought the heifers for fattening up and Charter Estates won many prizes at the agricultural shows.

A tapestry sewn by Lady Molly Salisbury, wife of Lord Robert Salisbury depicting Charter Estates 1946 – 1979; Courtesy of the Worthington Family

In 1980 Charter Estates was bought by “Benny the Bread” Lobel who sold to Lonrho in 1987.

Charter Estates and the Zeederberg Coaching Service

Zeederberg’s coaching services operated on the route through Charter Estate between 1892 and probably 1902, when Salisbury and Bulawayo were linked by railway line to the south and the coaching services were replaced by a weekly post cart that went each way between Salisbury and Enkeldoorn (now Chivhu)

Bernard Seymour Hall of Selukwe travelled by Zeederberg coach and wrote: “the passengers and driver had to be hardy folk to endure the jolting and swaying of the coach as it travelled at a canter over the rough, rutted, roads in the exhausting heat and clouds of dust. The coach generally travelled day and night; the only respite for the passengers was the short stops at stables to change mules and halts at bush hotels for meals. There were no bridges over the rivers and during the rains it was no uncommon event for the coach to be held up for hours, even days, at a flooded river waiting for the water level to fall sufficiently for the coach to pass through the drift. Along the coach routes at intervals of every sixteen or so miles were stables housing several spans of mules. As the coach neared the stable a bugle was blown by the driver, or his assistant, the sound carrying for miles over the silent veld to announce the coming of the coach and a span of fresh mules would be found waiting as the coach reached the stable all ready for a quick change. No time was wasted and it took only a few minutes to release the tired span from their harness and inspan the fresh mules. The leading pair of mules was often young, spirited, animals eager to go and they had to be held fast until with a shout and a crack of his whip the driver indicated he was ready to go. The men holding the leaders would let go and jump aside and the mules would rear up on their hind legs springing forward with a jerk on the harness that started the span off at a gallop.”

Bernard adds that mules were widely used for transport and gave this early description: “the buckboard, drawn by six mules, was a much lighter vehicle than the heavy old coaches and was used on many routes as a mail and passenger carrier operating in the same manner as the stage coach. They were also favoured as an elite mode of transport by business men and Government officials. On the Shabani - Balla Balls mail route buckboards were still in use in 1923 and, over the ninety-five miles run they averaged six and a half miles an hour notwithstanding stops at Belingwe and Filabusi Post Offices and at six stables changing mules. The Cape Cart, a high two wheeled vehicle drawn by two or four horses or mules was another means of transport much in vogue as a passenger vehicle in the early days. Tom Meikle, a renowned pioneer of commerce who had trading stores scattered all over Rhodesia had a beautiful spanking, turnout drawn by horses in which he travelled many hundreds of miles in a year visiting his businesses. The Utility Cart, a very low slung two wheeled cart drawn by one or two horses or mules, was a vehicle universally used as a light passenger conveyance. It was so low that the faces of the passengers and driver who sat side by side were level with, and not far from, the root of the animal's tail and it was embarrassing, if your passenger were a female, when the animal relieved nature or broke wind. The Scotch Cart was a sturdy two wheeled spring less cart capable of carrying a heavy load and it was much used on farms and on road or building construction. It was drawn by two or four oxen according to the load. It was a handy vehicle when traveling off roads through.”

Mill and Coach House at Charter Estates

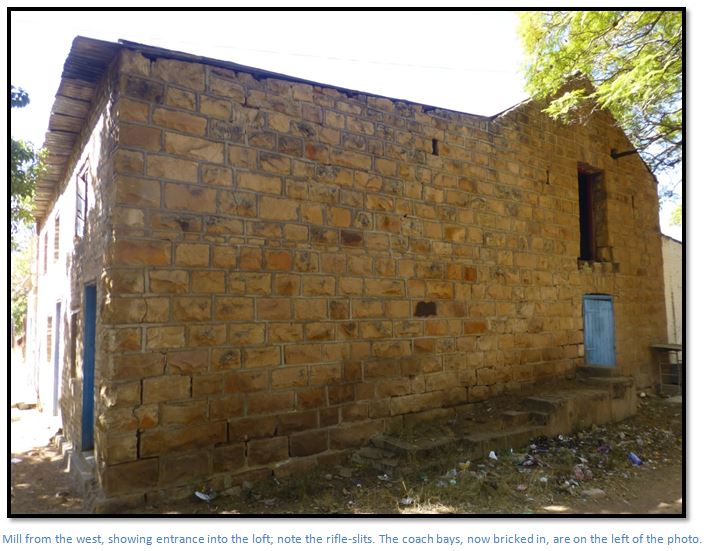

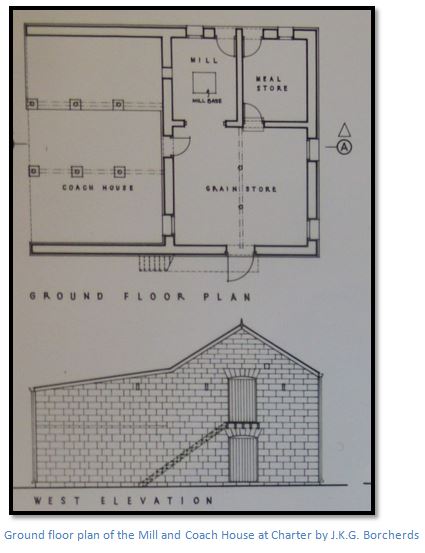

The Mill and Coach House are constructed of pale yellow sandstone quarried from a nearby source not currently known. The stones are rough dressed and squared and laid in courses and bedded in dhaka mortar and pointed in cement. The stone courses start larger at the bottom and become narrower at the upper parts of the building, but cover the full width of the walls. It is not known how deep the foundations extend. Footing walls are 61cm wide; internal walls 46cm, with the post bases in the coach house 46cm square.

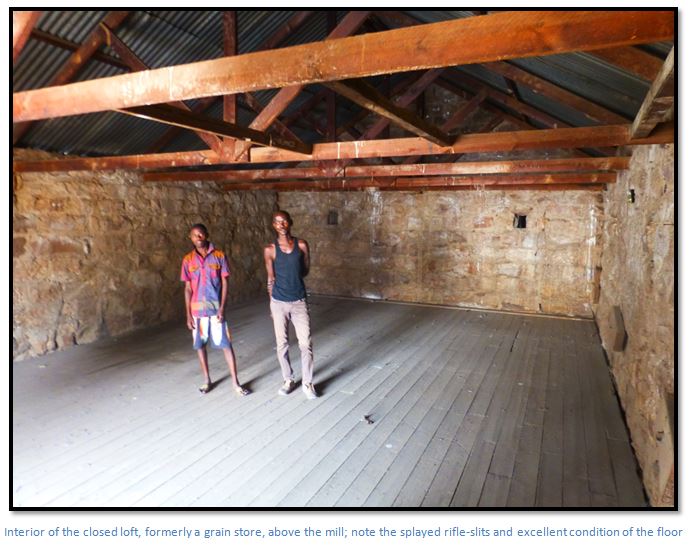

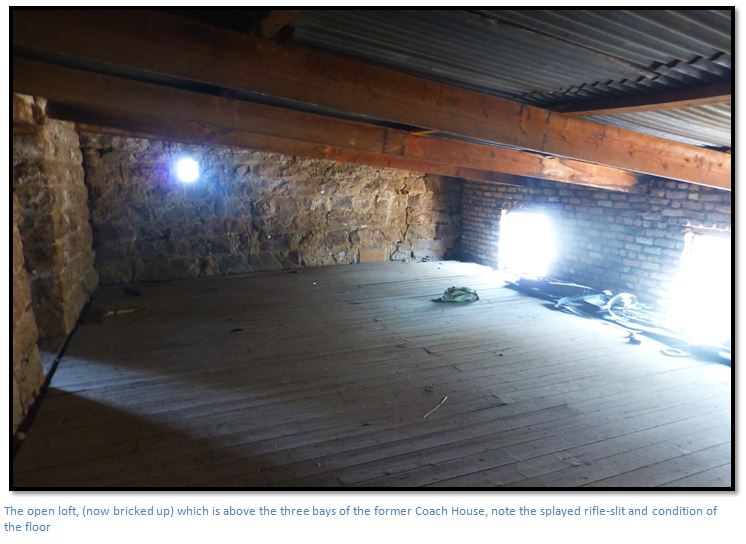

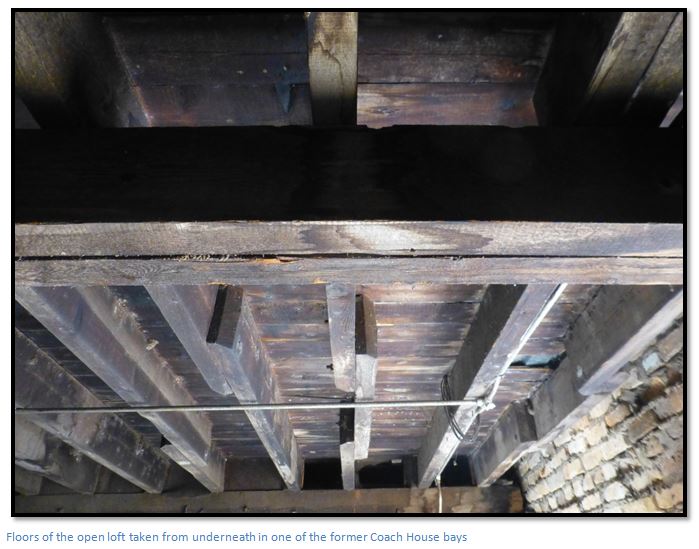

All openings have stone arches, or lintels, except the interleading door between the two lofts of the Mill and Coach House, which has a timber door frame. The roofs of both buildings are corrugated iron on purlins carried by sawn timber trusses, or rafters. Floors and floor joists and beams are constructed of sawn timbers and they all appear to be original.

The photo above shows the base of the original staircase, long since rotted away which led to a landing and the entrance to the loft. The remains of the timber beam, on which a lifting hoist would have been suspended to manually pull up bags of maize onto the landing and then into the loft, can still be seen above the landing. Today a ladder is required to access the loft.

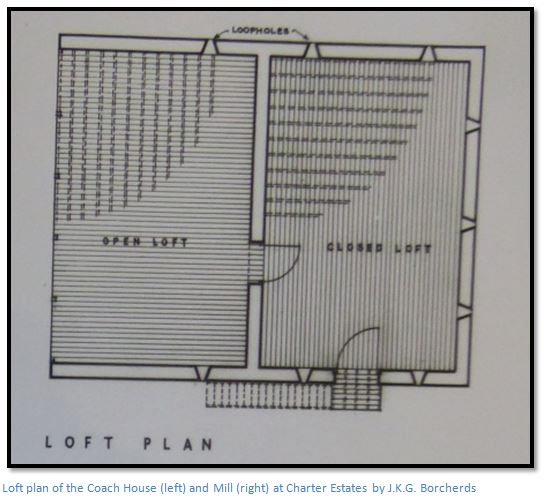

The lofts are semi-fortified with rifle-slits or loopholes which are splayed internally to give the defender maximum space and with their stout sandstone walls would have made formidable strongholds as they cover each other’s fields of fire.

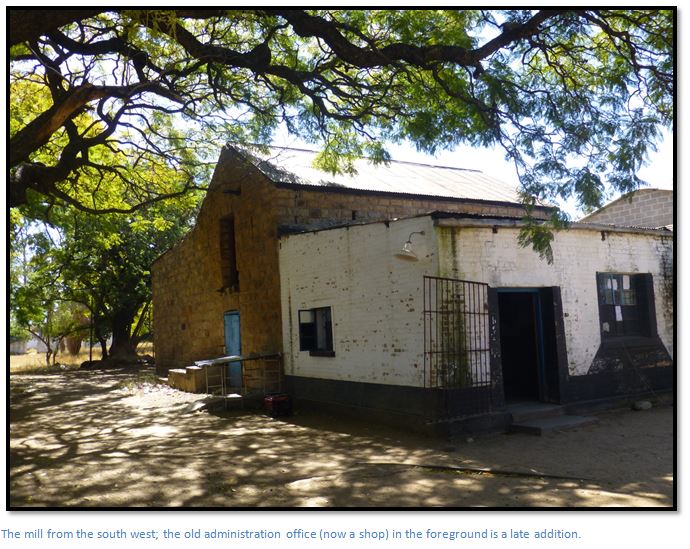

The workmanship in both buildings is of a very high standard and both buildings are still structurally sound after 124 years. Considerable additions have been made to both buildings over the years, but as the additions are always in brick and cement, they are easy to identify.

The external sizes of the Mill and Coach House are 9.2 metres (30 feet) east-west and 10.4 metres (34 feet) from north to south. Each of the coach bays is just under 2,75 metres wide (9 feet) to allow plenty of space so they can be manoeuvred backwards under cover.

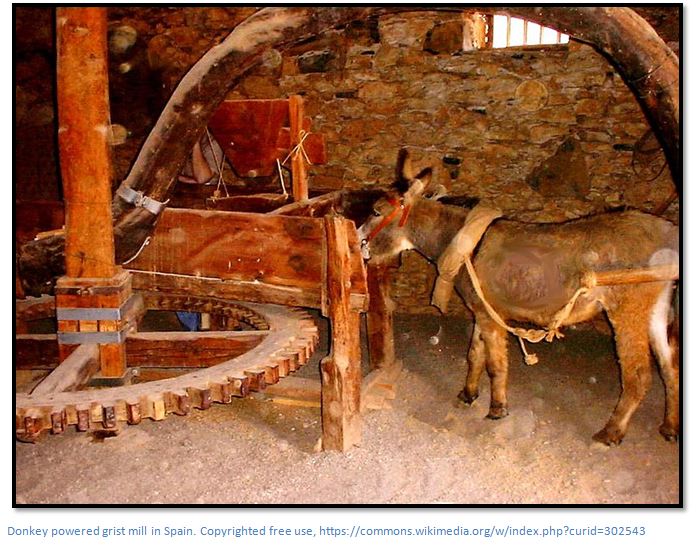

The ground floor of the Mill building originally contained the mill resting on the original sandstone base with an adjacent meal store. A wide entrance from the mill led through into the grain store which is now used a small shop. All ground floors were probably paved in stone, but they were later covered in cement render. When J.K.G. Borcherds carried out his 1960 survey, the mill was still in use.

The two millstones themselves would have been laid one on top of the other and turned at around 120 rpm. The bottom stone, called the bed, is fixed to the floor, while the top stone, the runner, is mounted on a separate spindle, driven by the main shaft. A wheel called the stone nut connects the runner's spindle to the main shaft, and this can be moved out of the way to disconnect the stone and stop it turning and the distance between the bed and the runner stones can be varied to produce the grade of flour required; moving the stones closer together produces a finer product.

The grain would be lifted in sacks into the loft via a hoist on the external timber loading platform. To mill the grain the sacks would be emptied into a hopper and carried down through a wooden shaft to the millstones on the floor below. The flow of grain is regulated by shaking it in a gently sloping trough (the slipper) from which it falls into a hole in the centre of the runner stone. The milled grain (flour) is collected as it emerges through the grooves in the runner stone from the outer rim of the stones and after being collected in sacks is stored in the meal store. The same process is used for milling wheat to make flour and for milling maize into maize meal.

There are no obvious indications of how the early mill was powered. Obviously it was not by water power, so perhaps a capstan was turned by animals, such as mules, which we know were present to haul the Zeederberg coaches. At some time it appears the eastern bay of the coach house was bricked up and probably contained a portable wood-fired steam engine which operated the mill by belt drive as there is a bricked up aperture in the wall. The floor of the eastern bay of the Coach House is also paved in stone, with the other two left unpaved. [See the articles on portable wood-fired “Colonial” steam engines at Kadoma Steam Centre / Halfway House under Mashonaland West / Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

It is known that European traders bought grain from the local Mashona farmers and after milling received back ground meal or flour, minus a percentage called the "miller's toll" in lieu of payment.

In order to prevent the vibrations of the mill machinery from shaking the building apart, a mill will often have at least two separate foundations.

The Coach House, occupying the ground floor space to the north of the Mill house has three bays, which appear from their height and size, to have contained space for three coaches to be sheltered under cover. Later the easternmost bay looks like it housed a portable steam engine, and in time the other two coach spaces were also bricked up; this ground floor space is also used today as a shop, but at one-time was a public call office, reputedly the first in the country.

Three of the ground-floor windows have been bricked up, but one frame remains. This is 10cm x 38cm timber with slots for louvres and presumably all three windows were originally the same.

Lean-to additions to the Mill house were added on the east for a mechanical workshop and the administration office of Charter Estates was added on the south side, but this is now another store.

The loft is divided into two sections. The closed loft under the pitched roof was being used in the 1960’s as a carpenter’s shop, but the remains of a gantry indicate a different use originally, probably as the grain store. Into the floor of the closed loft are the remains of an aperture through which unmilled grain would have fallen from a hopper down to the mill below.

The open loft, now clad with corrugated iron was used for general storage, possibly used for storing timber; hence the low height and the open side (now bricked up) for ease of handling and ventilation.

The floors of the loft comprise 15cm wide boards laid on joists which are carried on two 23cm x 8cm timbers beams which are bolted together. The beams are supported by 15-20cm undressed poles.

The roof is corrugated iron laid on purlins supported by rafters.

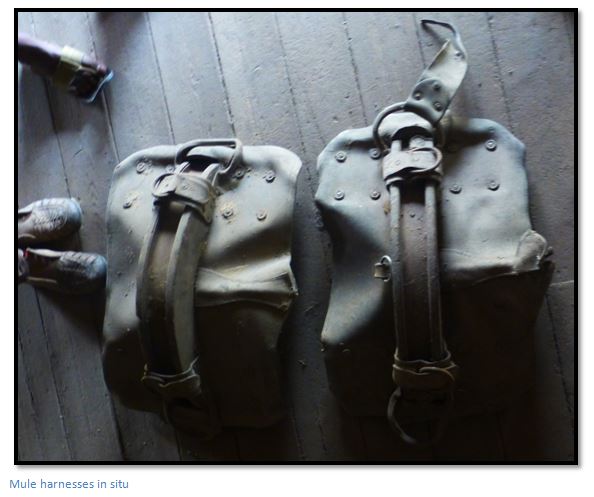

My attention was drawn during my first visit to two dusty mule harnesses lying in the loft. These have been collected and one each will be given to the Rhodes Nyanga Historical Exhibition and Mutare Museums which both collect items of early transport in Zimbabwe; both probably predate 1902 when the Zeederberg’s mule drawn coaching service ceased.

The Coaching Stables

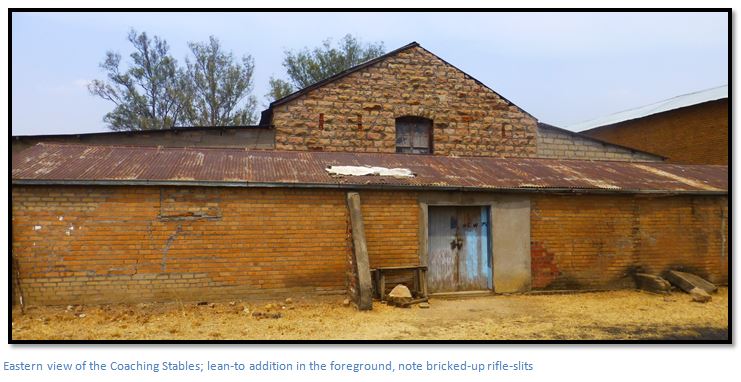

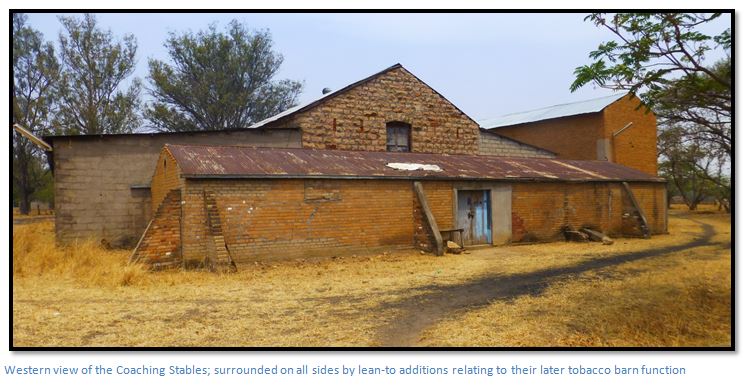

The original purpose of the building is still evident from the plan with the Stables below and a hay-loft above. Unfortunately extensive alterations have been made to the original building which was converted into a tobacco grading shed. Clearly at the time the Historical Monuments Commission did not realize the historical significance of these buildings, and they were not protected and listed as National Monuments.

To the west, tobacco bulk sheds were added. To the east are storerooms and a squash court. To the north, the lean-to shelter has been bricked in to form tobacco bale stores. To the south, cross walls have been built to form “mtepi” or tobacco stick stores.

The 45cm wide walls are built with the same rough hammer dressed sandstone blocks as the Mill and Coach House and are laid in courses and bedded in dhaka mortar with cement pointing; no foundation plinth is visible.

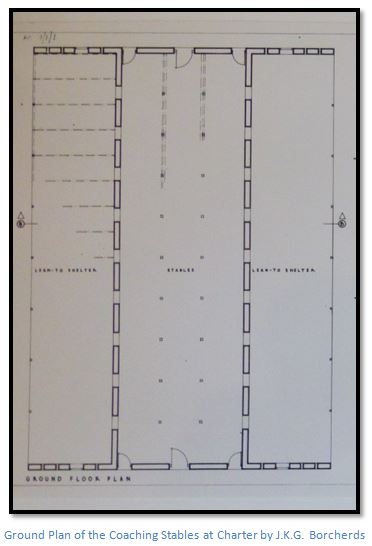

The Coaching Stables are 29.3 metres (96 feet) long; the actual Stabling and loft area is 8.5 metres (28 feet) wide, the lean-to’s are each 5.5 metres (18 feet) wide, making the total width of the covered area of 19.5 metres (64 feet) The height from floor to roof top is 7.3 metres (24 feet)

Internally great changes have also taken place. David Worthington says there was standing for 36 mules and horses and that there was a cobble floor, with the existing rendered cement floor added above it. The loft doors, the loopholes and stable windows have all been bricked up and today there is no sign of the original stalls which were provided for each mule.

It is difficult to visualize the stall arrangements now; but the pairs of small doors at either end probably gave access for feeding and watering the mules which assumes they were tethered with their tails towards a wide central aisle and their heads towards the water troughs and mangers with a narrow access to these along the interior of the external walls.

The windows no longer have timber frames, but were probably identical to those in the lean-to shelters which are 10cm x 7.6cm timber with slots for louvres.

When the building was converted into a tobacco barn, the entire timbered loft must have been cut down. The timbers were originally on joists which were in turn carried by beams supported on posts. All timber posts have been removed, but there are signs in the south lean-to of posts which originally supported the beam carrying the rafter ends. The positioning of the posts in the plan is based on J.K.G. Borcherds’ architectural knowledge of such positioning and the fact that the ends of the bearer beams still exist.

The hay-loft had splayed rifle-slits or loopholes similar to those in the Mill and Coach House, but they are now bricked-up. There were ten on each of the southern and northern sides accessed from the loft floor and each of the east and west faces had four on the loft floor and six at ground level protecting the entrance doors. Originally access to the hay-loft was probably external onto the loading platforms with a gantry and hoist at either end.

Borcherds did not think the existing roof lights were original as such a large expanse of glass would have been difficult to obtain around 1892 – 1894 and the hay-loft would have been sufficiently lighted with the loop-holes and two large doors, so they were probably added when the Coaching Stables were converted into a tobacco grading shed.

The corrugated iron roof is laid on 8cm x 5cm purlins

The original purpose of the lean-to shelters on the northern and southern sides is not evident; they have earth floors and they may have been used to protect laden ox-drawn transport wagons, their crews and harness. The western side is currently used as a carpenters shop.

Acknowledgements

J.K.G. Borcherds, “A Brief Description of Fort Charter”, September 1960. BO 9/1/1 National Archives, Harare.

Tony Mirams for photographs, letters and bringing J.K.G. Borcherds’ Charter Estates survey to my notice.

J. Meikle for his Notes on Jeannie Strickland (née Meikle)

Mr Kagahande and Harold Mhundwa for assistance at Charter Estates

D.K. Worthington. Early Days at Charter Estate. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 10, 1991. Pages 93-98.

M. Worthington. Notes on D.K. Worthington and photographs.

C. Lloyd. Fort Charter. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 11, 1992. Pages 123-130.

Memoirs of D.G. Gisborne, 1893 Column. Rhodesiana Publication No 17. December 1967.

Wikipedia

Colonel A.S. Hickman. Men who made Rhodesia. The British South Africa Company. Salisbury, 1960

R. Cherer Smith. Rhodesia, a Postal History. Salisbury. 1967

The reminiscences of Bernard Seymour Hall of Selukwe formerly of the BSAP, provided by his son Bernard Seymour Hall in http://www.rhodesians-worldwide.com/rwmagazines1/Vol171/f