The British South Africa Company and the impact of early gold mining regulations on smallworkers

In most parts of Southern Africa the landowner had the sole right to prospect on their farm, but this was not the case in Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. The British South Africa Company (BSACo) through the Rudd Concession reserved all the mineral rights for itself. [See the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd Concession under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

However from earliest days the whole country was thrown open for prospecting except for areas which had already been registered as mining claims or were occupied as townships. The only restrictions as regards pegging claims were as follows:

- On occupied farms mining claims could not be pegged within 500 yards of the principal homestead, or within 100 yards of any building with a value of £100 or more.

- No claims could be pegged between the hours of 6pm and 6am

- Mining claims could be pegged up to roads or railways, but no excavation work could be done within 50 feet of the centre of a road or 150 feet of the centre of a railway.

- No claims could be pegged on cultivated land without the written permission of the owner or occupier.

Mining regulations 1890 - 1924

The early mining laws of Rhodesia were based on the fact that from the beginning the

British South African Company[i] (BSACo) was granted rights over all mineral wealth.

The mining laws fall into two periods:

1890 – 1903; only limited companies could exploit gold bearing deposits. If a prospector discovered a payable gold reef he could make a claim, but he could not mine it. He had to arrange with the BSACo to form a syndicate or company for this purpose.

The standard condition was that the syndicate or company would award the BSACo 50% in the business in return for granting mineral rights. However terms varied at the BSACo’s discretion and groups that promised to make large investments or were represented by well-known individuals received better terms. Albert Grey, a BSACo director was in a syndicate which received 35,000 acres and 40 gold claims in return for one-third of the net profit rather than 50% of the share capital. The Anglo-French Exploration Co was given 100 gold claims in return for 40% of the net profit provided they spent £90,000 on exploration within two years. The Mazoe Syndicate led by Edward Maund was given 2,000 acres for every ore-crushing stamp erected to a maximum of 30 stamps. Other concessions from the 50% of the equity rule were granted at the BSACo’s discretion.[ii]

In 1902 in view of the problems the gold mining industry was experiencing the free-carried BSACo share of the business was reduced from 50% to 30%

1903 – 1924; after 1903 the claim holder could work the gold claims on his own account on payment of a royalty to the BSACo.

The 1890 regulations contained the following rules:-

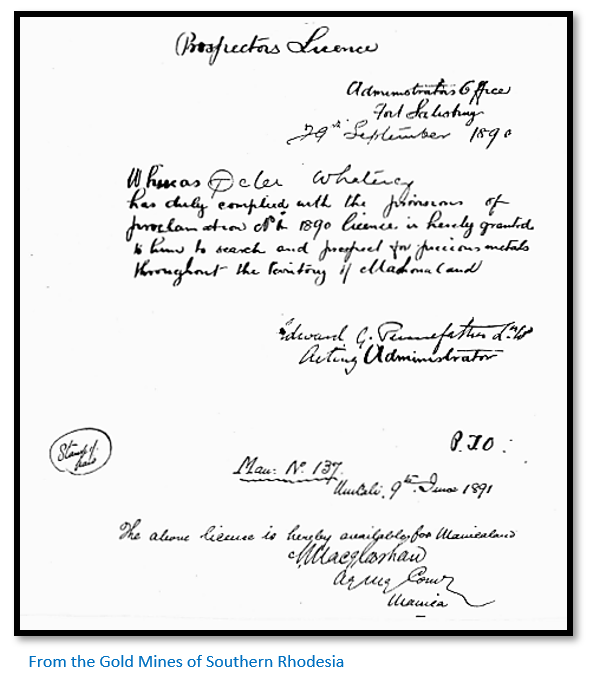

Prospecting Licence -Fee 1 shilling

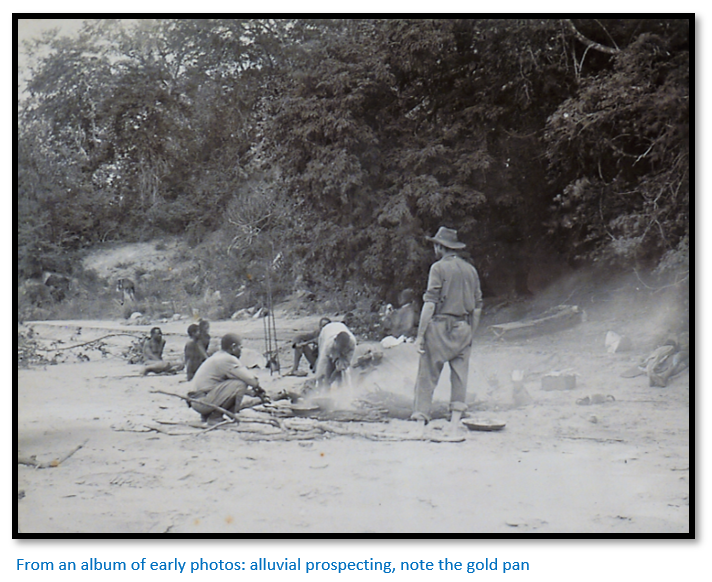

A prospecting licence could be obtained from any Mines Office and entitled the holder to search for minerals and if they were successful to peg a block (of up to) ten gold reef claims, or alternatively one alluvial claim, or one base metal claim.

This Prospectors Licence to Peter Watney[iii] above signed by Edward Pennefather, Acting Administrator of Mashonaland is dated 29 September 1890 shortly after the flag raising ceremony on 13 September 1890 and even before the Pioneer Corps was officially disbanded on 1 October 1890.

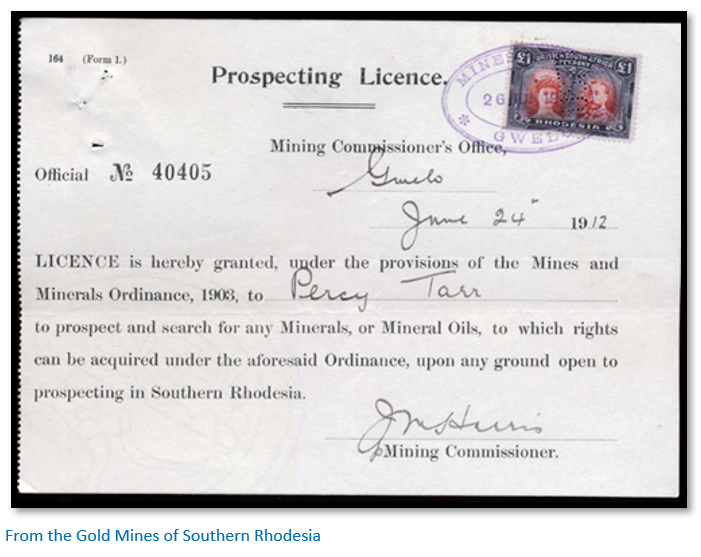

The later prospecting licence numbered 40405 issued to Percy Tarr at Gwelo on 24 June 1912. As can be seen the fees paid for licences were receipted by stamps to the value of the fee. The prospector was required to carry his licence with him at all times and produce it on demand to any duly authorised official. In the early days the prospecting licences was required to be submitted to the Mining Commissioner with the application for a Certificate of Registration, so very few prospecting licences have survived.

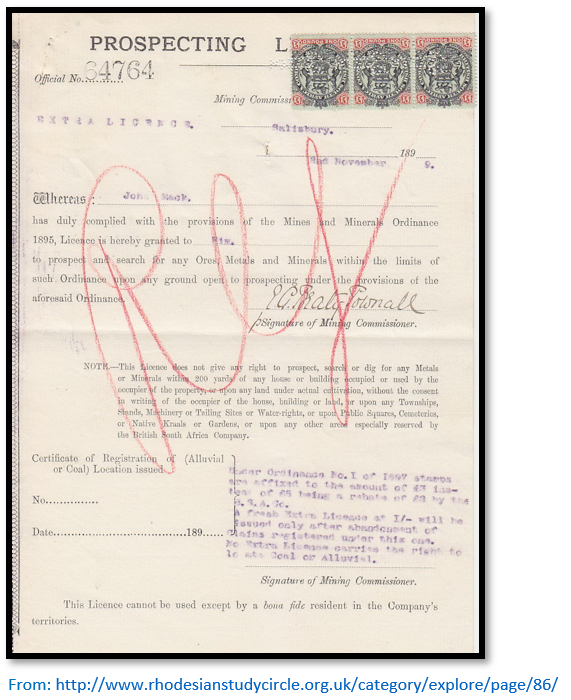

The above prospecting licence issued in 1899 to Jon Mack who registered several blocks of claims including Nos 2248 & 2249 on 28 May 1900 20kms north west of Gatooma and formed on 29 September 1902 Golden Valley (Mashonaland) Mines Limited. Golden Valley became a showpiece mine and on his death the Jon Mack trust distributed large payments to many local charities for many years.

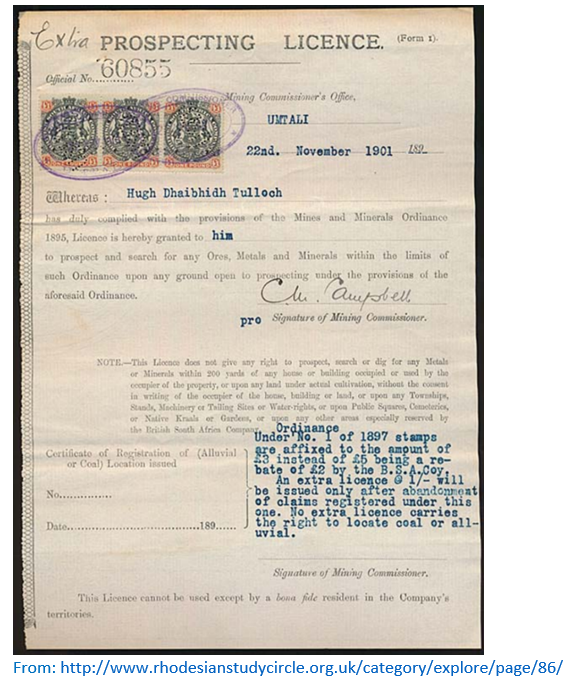

The above 1901 prospecting licence was issued to Hugh Tulloch at Umtali in 1901. I am not sure of his relationship to Alexander Tulloch, a trooper in C Troop of the Pioneer Column who took part in the battle of Massi-Kessi (Macequece) and who became an Umtali auctioneer and later Nyanga farmer and who prospected and mined at Penhalonga for many years on the Liverpool, Campion and Central Penhalonga Mines. [See the article Penhalonga under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

1890 – 1896: initially a prospector could only have one licence, and could not obtain another until he had either abandoned the claims registered under it, or had executed 30 feet of development work on the claims and obtained an Inspection Certificate.

1897 – 1902: extra prospecting licences could be obtained permitting an unlimited number of claims, subject to payment of £5 for each block of ten claims, later reduced to £3.

1903 onwards: the earlier restrictions were abolished and prospecting licences cost £l with no restrictions as to the number of claims.

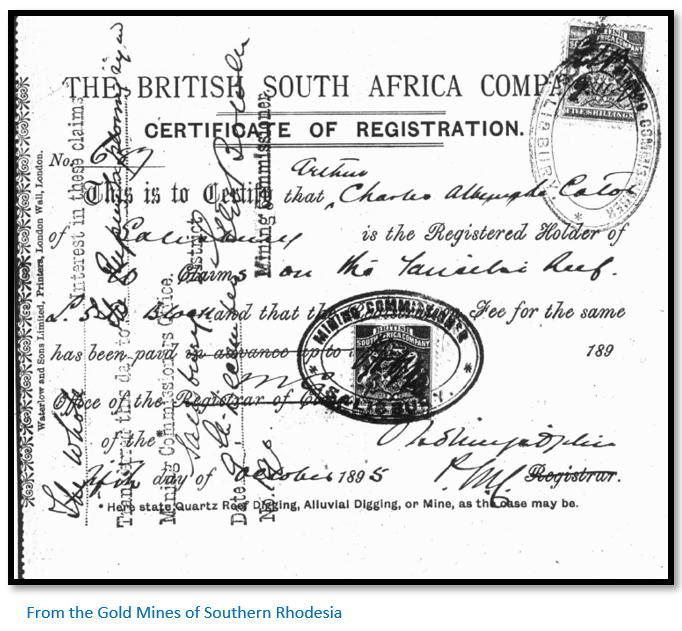

Certificate of Registration - Fee 5 shillings

After registering a block of claims, the prospector would receive a Certificate of Registration. The BSACo and the prospector had equal shares in all claims, but the claimholder had to sink a shaft of at least 30 feet within four months or lose the claim.

Laying out claims

(1)Gold reef - If gold was discovered, the prospector could mark out on the ground a quartz reef claim 150 feet by 400 feet. Ten such claims could form a block 1,500 feet by 400 feet.

A block of ten gold reef claims would run 1,500 feet along the strike of the reef, with a width of 400 feet (amended after 1895 to 600 feet)[iv] It had to be pegged in rectangular form with the length of the sides given. Where because of the proximity of other previously pegged claims an irregular block had to be pegged, the greatest distance between any two pegs was not to exceed 1,500 feet.

(2)Base metal – these blocks had a maximum size of 30 gold reef claims and could be pegged in any shape with a maximum total area of 2.7 million sq. feet.

Procedure for pegging claims

First a prospecting notice needed to be posted on the area to be prospected. If mounted on a board it needed to be at least 9 x 9 inches and fixed on an upright support in a conspicuous position.[v] The posting of the prospecting notice gave the prospector the exclusive right of prospecting for 31 days within a radius of 1,000 feet for gold. (3,000 feet for base minerals)

For gold claims, a straight line needed to be measured for 500 yards along the strike of the reef with pegs marked E and F at each end. The corners are then fixed by measuring 100 yerds at right angles from the centre line and corner pegs clearly marked with the letters A, B, C and D.

Within 31 days of posting the registration notice, an application for registration needed to be made to the Mining Commissioner in the district in which the claims are situated with a fee paid of 5 shillings per block for gold claims and £1 for base minerals.

The following documents then needed to be lodged at the Mining Commissioners office within 31 days or a further 31 days if an extension was obtained for good reason:

- The prospecting licence used

- A copy of the discovery notice

- A sketch plan showing as clearly as possible the physical position of the claims with the name of the farm they are situated on if applicable.

If not done within the time period the prospectors’ right would lapse and the ground became available for re-pegging after 7 clear days after lapsing.

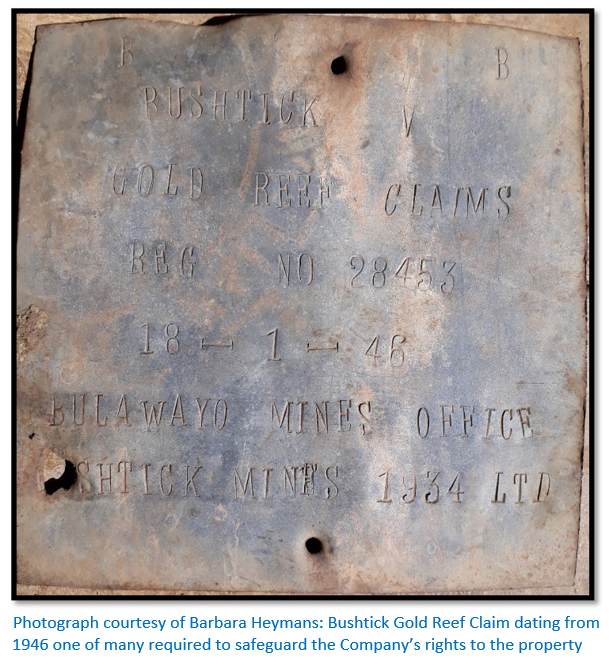

Permanent beacons to replace the temporary pegs needed to be erected within 4 months of registration with claim plates fixed to them giving details of the name of the reef, registered number, date of registration, district and name of owner.

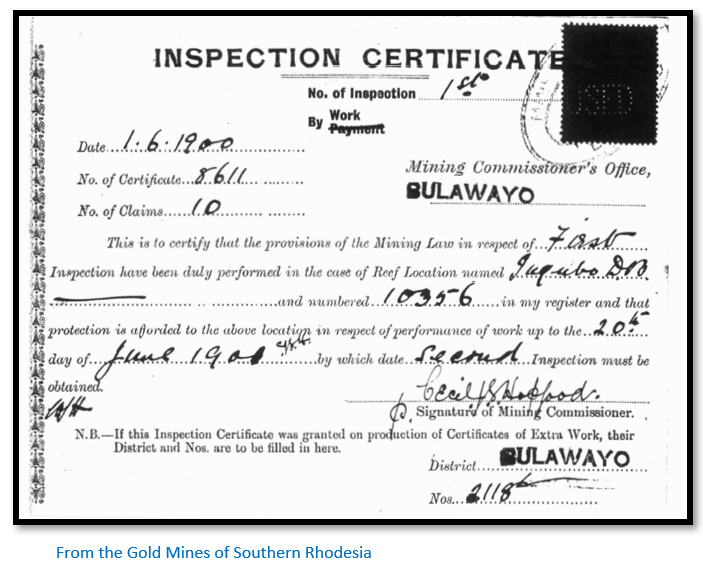

Inspection Certificates - Fee 10 shillings

An official inspection was carried out to check that the required work of 30 feet of excavation had been done and a lnspection Certificate was issued.

After 1895 at least 60 feet of excavation was required each year, in addition to the 30 feet required in the first four months under the 1890 Regulations.

The first lnspection Certificate above in respect of Ingubo gold claims was issued on 20 June 1900. A second Inspection Certificate was required under the 1890 regulations within 12 months.

An annual report of the amount of excavation work had to be submitted, and an Inspection Certificate obtained. In default of work, the BSACo could issue a lnspection Certificate by payment. Originally a first lnspection Certificate cost £30, and a second lnspection Certificate £60. Under the 1895 Regulations, a claimholder could not obtain a certificate by payment for two years in succession, the claims needed to be inspected at least once.

In 1898 new rules for inspection by payment were introduced, the first certificate costing £5, the second certificate £10, the third and fourth certificates £20 each and fifth and subsequent certificates £30.

In 1903 the Mines and Minerals Ordnance 1903 consolidated the earlier legislation with certain modifications. The earlier system of carrying out certain work and obtaining Inspection certificates persisted until 1907, but a new system was then adopted which led to the end of inspection by payment by 1914.

After 1 January 1908 a claim holder had to carry out 30 feet of development work in the first six months or pay £5; he had to do the same in the next six months or pay £15. Thereafter the law was strictly applied and unless 60 feet of development work per annum was carried out the claim was forfeited. Inspection by payment was therefore no longer available except during the first year following registration.

Alluvial mining claims

Inspection Certificates did not apply to alluvial gold claims which were charged at £1 per month, payable in advance. A certificate showing the amount paid and the period in respect of which it was paid was issued by the Mining Commissioner with stamps to the value of the amount paid.

An alluvial claim on a river measured 150 feet by 150 feet. By 1934 this had been changed to a maximum of 200 sq. feet.[vi]

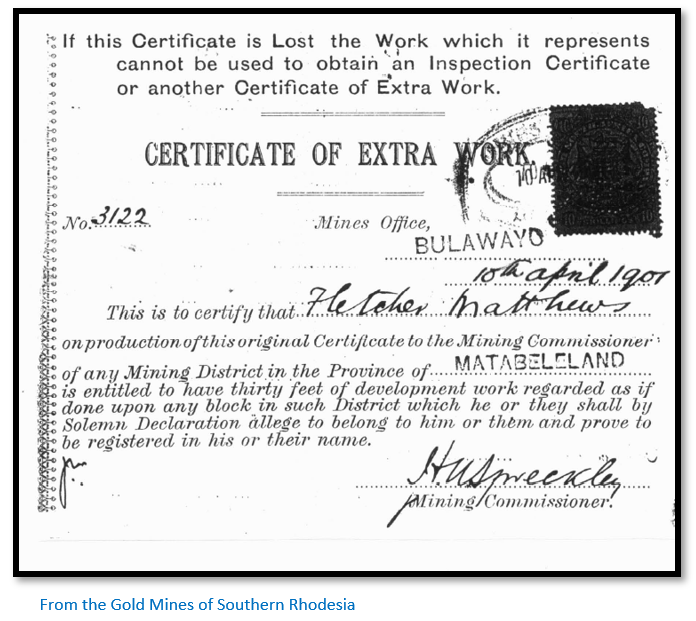

Certificate of Extra Work - Fee 10 shillings

The owner of several blocks of claims, who carried out more than the minimum work

required on one block (i.e. 30 feet in the first year, 60 feet in subsequent years) could obtain a Certificate of Extra Work, which exempted him from the same work requirements on another claim. This was a valuable concession, because the failure to carry out the minimum excavation work brought about the forfeiture of a claim. Once the minimum work required on one block was done, the claimholder could apply to the Mining Commissioner for a Certificate of Extra Work for each unit of 30 feet of work done and the certificate obtained entitled that work to be regarded as done on any other claim owned by that person.

The Certificate of Extra Work was kept by the Mining Commissioner for the district. The particulars of each lnspection Certificate issued as a result of a Certificate of Extra Work had to be endorsed upon that certificate.

After 1 January 1908 the rules for Certificates of Extra Work were also amended and claimholders were only exempted from work on bordering mining claims.

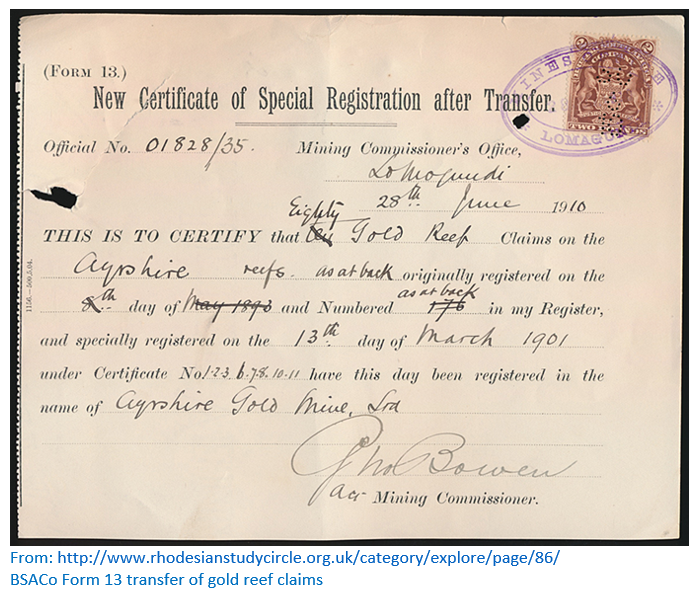

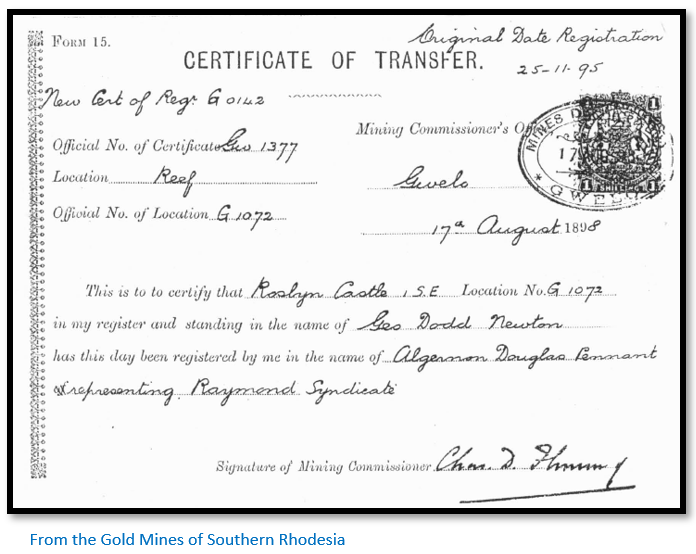

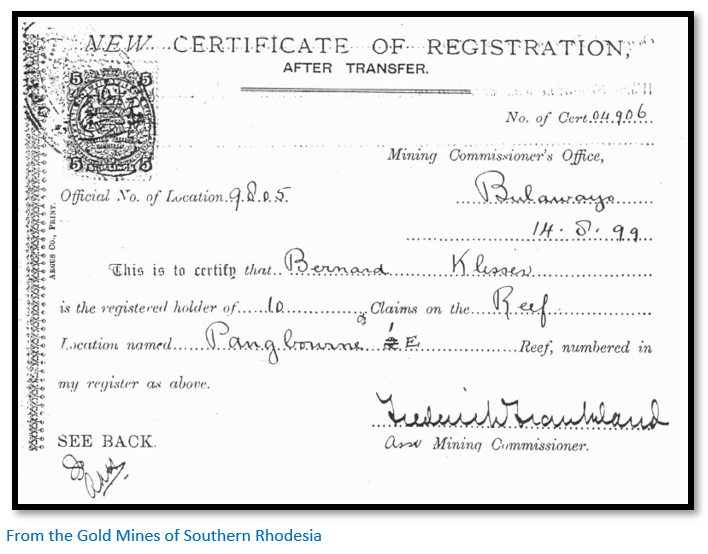

Certificates of Transfer (Forms 13 and 15) - Fee 5 shillings

Mining claims were transferable between persons and companies , but a transfer had to be registered by the Mining Commissioner, otherwise the transfer would not be valid. The Mining Commissioner issued to the new owner a new Certificate of Registration which also required a 5 shilling stamp.

After 1903 the stamp on the Certificate of Transfer was a minimum of £1 and if the purchase price of the transfer exceeded £100, then the fee was £1 for every £100 or portion thereof.

The above transfer form issued at Lomagundi on 28 June 1010 certifies that 80 gold reef claims originally registered in the name of the Ayrshire Reefs in 1901 have been transferred into the name of the Ayrshire Gold Mine Limited.[vii]

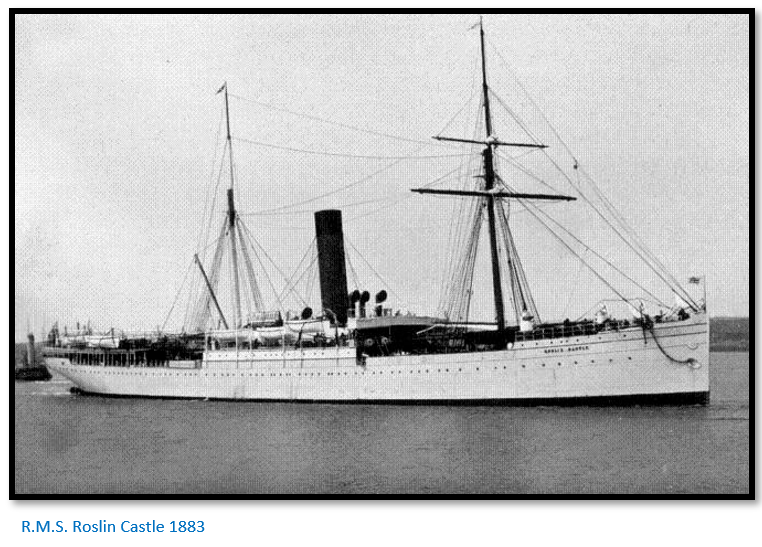

Above the Roslyn Castle[viii] gold claims transferred from George Dodd Newton to Algernon Douglas Pennant representing the Raymond Syndicate on 17 August 1898. The original registration is noted as 25 November 1895.

There were certain transitional provisions in respect of registrations already in being before 1908 and a new concept of a Certificate of Special Registration, which gave indefeasible title, was introduced, on payment of a fee of £1 and after going through a specified form of enquiry before the Mining Commissioner.

New Certificate of Registration after Transfer

After mining claims were transferred a new Certificate of Registration would be issued in the name of the new claim owner with details of the old owner referenced to the mining register on the back of the certificate.

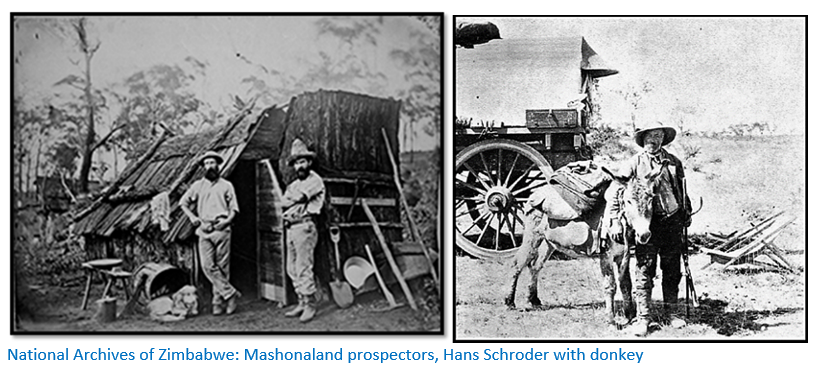

Gold prospects in 1890

The young men of the Pioneer Column were not paid salaries: they expected adventure and hoped for riches at the end of the trek…the BSACo had contracted to pay them with 15 gold claims and farms of 1,500 morgen (about 3,175 acres) for their services as troopers. Most of them would quickly sell their farms – often for £100 to the firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow. Stories of how the supposed rich surface deposits of gold could be found using pick and shovel made recruitment to the venture easy. They had heard that Mashonaland contained gold deposits richer than the Rand and that it was easily accessible, unlike the low-grade deep mines of the Rand which required vast amounts of capital.

After his return with Henry Hartley from the Tati and Hartley Hills Carl Mauch had written in a letter printed in the Transvaal Argus on December 4, 1867: “how the vast extent and beauty of these goldfields are such that at a particular point I stood as if transfixed, riveted to the place, struck with amazement and wonder at the sight and for a few minutes was unable to use the hammer.”

Mauch’s enthusiasm had got away from him in his description of the vast extent of the new goldfield, of how countless thousands of people had found fortune on them in the past, and of how he was certain that countless more thousands would find wealth there in the future. The news caused an uproar in South Africa and was soon circulated around the world.

Major A.J. Leonard wrote: “My sole idea in coming out was to be the first to see the ancient El Dorado under a new name.”[ix]

The BSACo was undercapitalised to develop the new territory of Mashonaland

The share capital of the Chartered Company of £1 million was by no means adequate considering it was envisaged railway construction from Mafeking would cost £700,000 and £200,000 was provided for preliminary development of the company.[x]

The goldfields of Mashonaland failed to provide any real returns to the BSACo investors - the costs of railway construction and maintaining the British South Africa Company Police (BSAP) force continued to mount. The Pioneer Column, even though its mainstay were volunteers cost £90,000. By the end of 1890 the BSAP force consisted of 650 men, each costing £300 a year, a total of £195,000 annually which was unsustainable. The force had to be reduced to 100 men by the end of 1891 and to 40 men the following year.[xi]

However the Board of Directors avoided attacking Rhodes directly for the excess expenditure, instead concentrating on his subordinate, particularly Major Tye responsible for the BSAP commissariat. The London secretary Herbert Canning writing: “The board cannot understand without further explanation how the affairs of the Company could have been allowed to drift into their present condition.”

Newspapers by 1892-3 were publishing articles saying the long-held views on Mashonaland’s riches were largely a fantasy. Randolph Churchill’s book Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa, who might have been expected to be positive as a BSACo shareholder and friend of the Directors, was distinctly negative about its mining prospects. [See the article Lord Randolph Churchill’s visit to Rhodesia in 1891 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

BSACo shares that sold for £2.1s.2d when first floated on the London Stock Exchange in early 1891 after the publication of Churchill’s book in February 1892 had dropped to 12s.6d.

Rhodes was forced to request help in the form of loans of £60,000 per year from De Beers and Consolidated Gold Fields in 1893 – 4 and in return De Beers was given exclusive rights to work any diamond fields and Consolidated Gold Fields received rights to 250 gold claims in Matabeleland and 108,000 acres (51,000 morgen)

BSACo finances would not be employed in mining operations

The Chartered Company did not contemplate entering mining on its own account at any stage although we have already seen that through the Rudd Concession it reserved all the mineral rights for itself. They hoped to encourage individuals and syndicates to invest their own capital. However the mining regulations between 1890 – 1903 stated individuals could register a gold claim but could develop it. They had to arrange with the BSACo to form a company for this purpose.

Even this did not deter the early gold prospectors’ passion and many after selling out their gold claims re-invested the money in syndicates as enthusiasm for the future of gold discoveries remained high. “Within three months after the arrival of the Pioneer Column at the site of Fort Salisbury [13 September 1890] twenty-two syndicates had been formed in Kimberley alone for mining operations in Mashonaland. Parties were organising throughout South Africa and the fever had touched investors in Britain.”[xii]

By the end of July 1894 a total of 34,560 gold claims had been registered.[xiii] However very few operating mines produced sufficient gold to justify the expense of transporting the mining machinery required to mill the ore from the railhead at Vryburg.[xiv]

Galbraith writes that most companies were over-capitalised with their promoters reserving large proportions of the shares to themselves before allocating the BSACo its 50% share…consequently there was little working capital for mining operations. “Speculators and directors who did not ‘know a mine from a railway cutting’ controlled the companies in early years and the pre-occupation of stock exchange transactions rather than on mining was abetted by the chartered company policy which imposed no requirement of serious development.”[xv]

Even Jameson admitted that: “even up to the death of Queen Victoria [22 January 1901] we never had any real prospecting. All the prospecting done was then pegging old workings.” The extravagant early hopes of a second even richer Rand than the Transvaal were disappointed by the early exploration and mining results, the often speculative and fraudulent share flotations and finally the Matabele and Mashona rebellions of 1895-6.

Of the 22 best-known Rhodesian mining and development companies listed locally, between 1895-8 most of their share values fell by 50% and some by 90%. Phimister states that of the £10 million cash invested in mining, dividends paid were paltry. 1899 - £26,000; 1900 – nil; 1902 - £130,575, an amount not exceeded until 1909.[xvi]

This situation continued with the manpower shortage until after the Anglo-Boer War (11 October 1899 – 31 May 1902) when the BSACo’s mining regulations were changed to allow individuals to carry out mining activities and they were permitted to pay a royalty rather than surrendering 50% of a syndicate or company’s shares.

Michell report to the BSACo in 1903

Phimister reports Michell’s dire description of the Southern Rhodesian mining industry at the time as follows: “Perhaps, beyond all, there remained the fact that the mining companies except where backed by strong financial groups, had practically arrived at the end of their resources and were finding the London market in no mood to absorb fresh issues of speculative capital. It seems clear…that the Rhodesian Gold Mining Industry has been started on inadequate working capital, has expended far too much on surface works, has not studied economy of management either locally or in London, and hence that a process of reconstruction is inevitable…Over capitalisation has been the curse of the country, and the scattered and often lenticular formation of the reefs in Rhodesia, leads me to think that the interests of the gold industry…will best be served by the encouragement of small and economically worked concerns.”[xvii]

Specific features relating to the Rhodesian Gold Mining Industry

A basic revision of the investment realities was necessary because:

(1)“In Southern Rhodesia payable gold occurs most frequently in short, narrow and lenticular quartz reefs, the gold is freakish in occurrence and unpredictable in distribution” and

(2)Because of the “great technical mining uncertainties…found in conjunction with, on the average, only a short mining life” [of individual mines][xviii]

As a result in 1903 the mining regulation that only limited companies could exploit gold bearing deposits was relaxed

Under the 1903 Ordnance, the previous rule that the actual working of a mine could only

be carried out by a company, in which the BSACo had to have a 50% share, was changed to include:

- Either a company in which the BSACo had a 30% share,

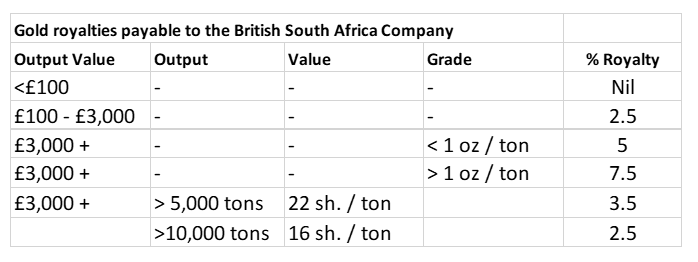

- Or a claimholder / tributor could work his own mine if production was under 750 tons per month and where profits exceeded £100 monthly pay a royalty of 2.5%. The royalty was reduced to 5 shillings if there was no working in the month or if the amount extracted was less than £100.

Then later the same year Government Notice 212 extended the mining regulations for larger outputs and introduced a sliding scale of royalties:

The beginning of the smallworker in gold-mining

The smallworker or individual miner, first came into existence in 1903 when the

BSACo first permitted miners to work for profit without the necessity for a company flotation.[xix] They flourished because the smallworkers were able to operate at a profit on a deposit too small, or too poor to interest larger companies, and thus produced considerable quantities of gold that would otherwise have been lost to the Colony.

Phimister notes in his article on the Southern Rhodesian gold-mining industry 1903-10: “the period is characterised by the encouragement and emergence of small-scale, local capital within the industry, a feature which sharply distinguished Southern Rhodesian mining from both the South African Rand and the later development of the Zambian Copperbelt.”[xx]

1907 regulations were designed to further open up the local gold mining industry

This change involved the holding, inspection and working of gold claims. It was intended to force companies to release many of the unworked claims they had ‘locked up’ during and after the speculative 1890’s.[xxi] This did indeed release many gold claims and the mining industry expanded greatly in the next 6 years.

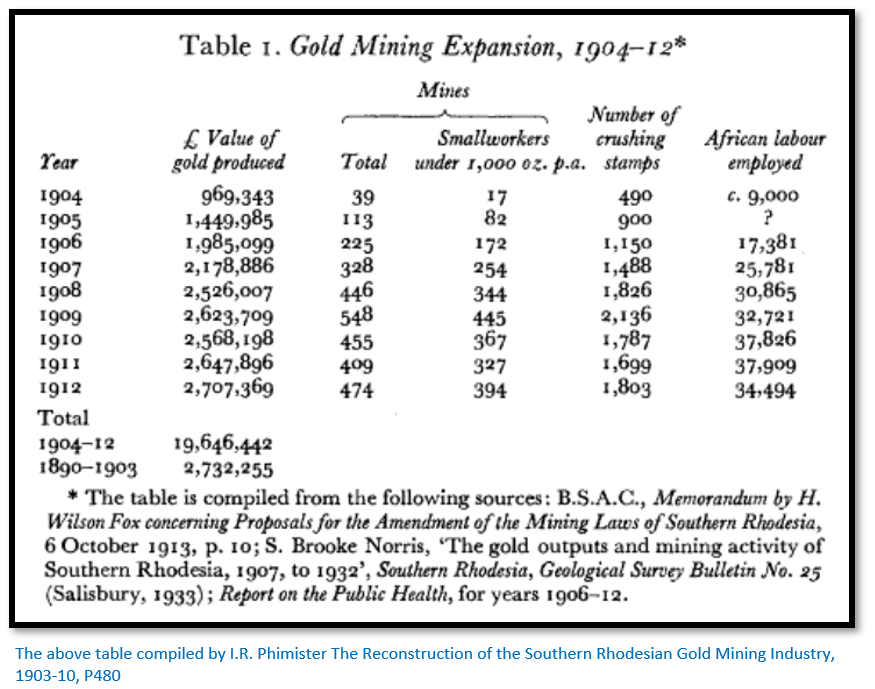

In 1905 there were 76 smallworkers, the number more than doubled in the next year and by 1907 there were 254 mines each producing less than 1,000 ounces of gold annually.

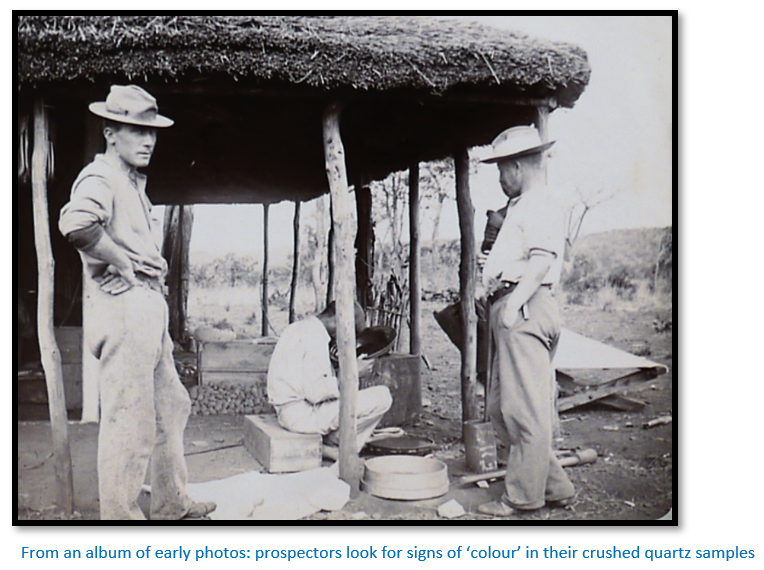

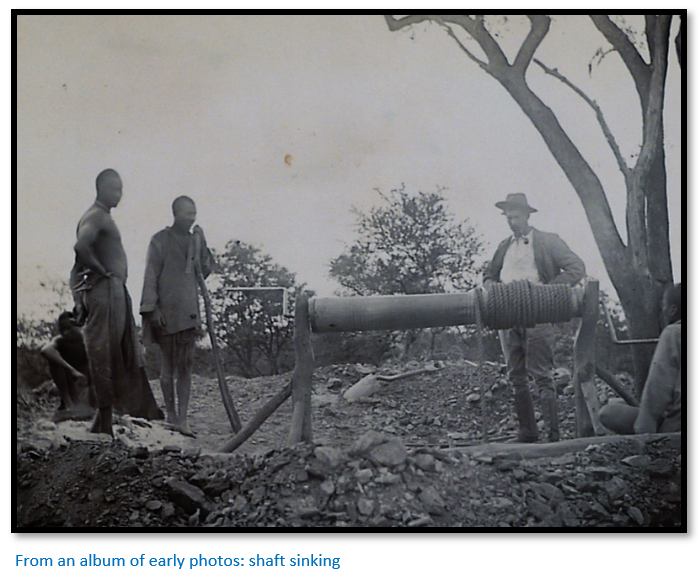

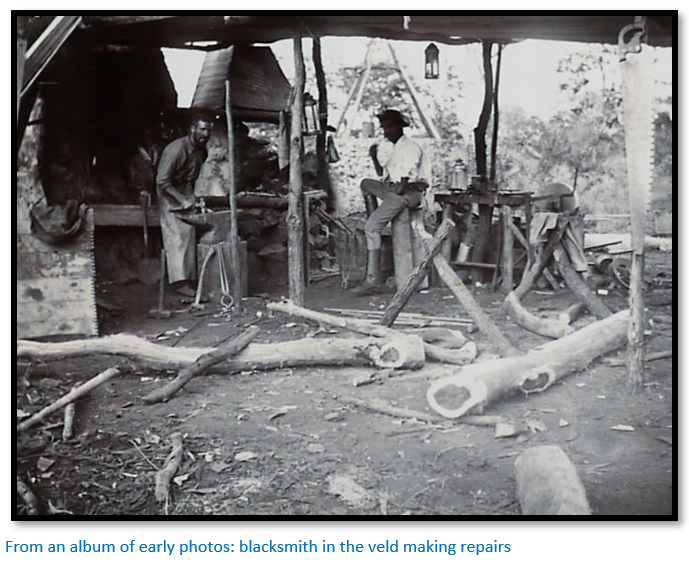

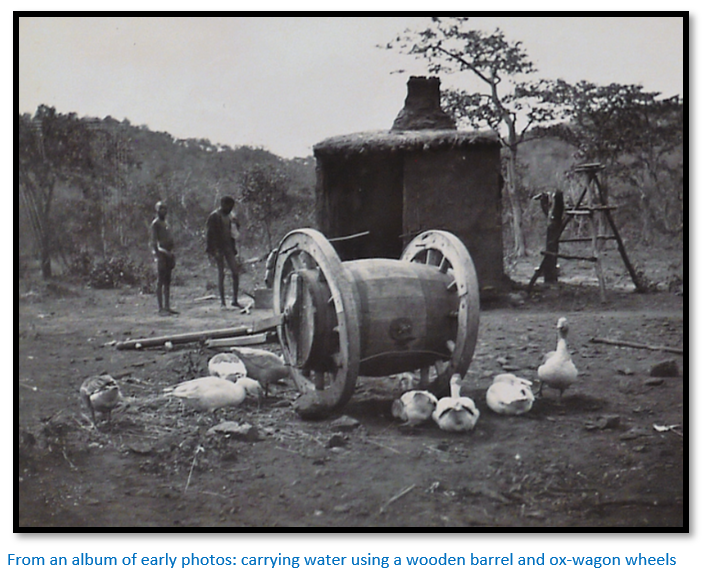

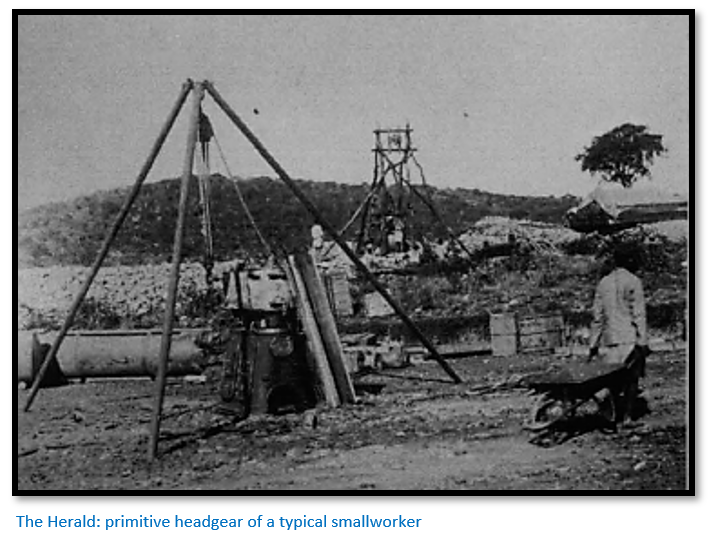

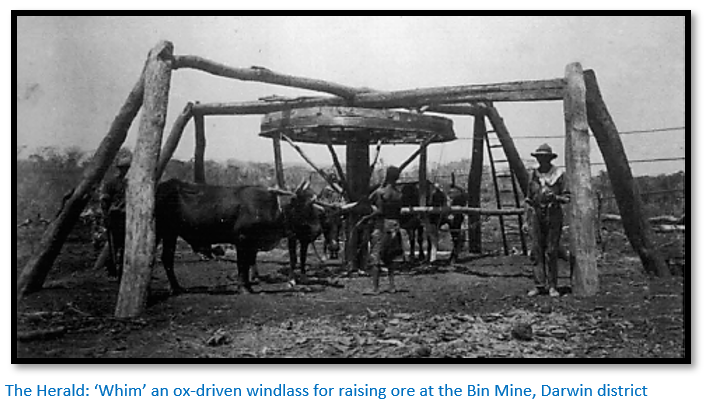

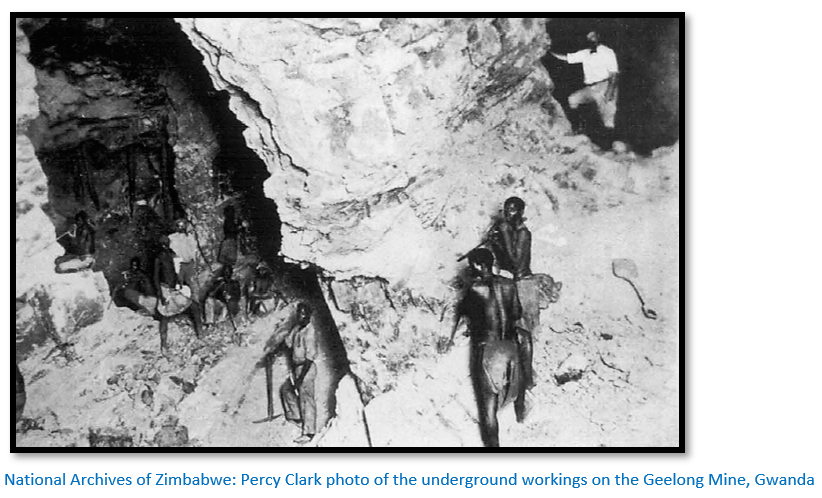

Typical smallworker equipment

This often consisted of a small crushing plant, a two or three stamp mill and normally no more than five stamps, a small cyanide plant with tanks (if at all) a boiler and a pump. Those without a pump worked the property down to the ground water level. £2,000 was enough to fit out a smallworker with a two-stamp mill and permit development work, a bigger five-stamp plant cost £3,000-£5,000. Often the BSACo advanced the funds on easy repayment terms.

The very low capital requirements of the smallworker was ideal for working the country’s quartz reefs and the Financial Times noted: “These men working for themselves are great hustlers and do wonders often with very simple and inexpensive plant. They bring into requisition all sorts of crushing plant and find partners as good miners as themselves, with a little ready money to share with them in any promising venture.”[xxii]

Life of the smallworker

Percy Hone wrote this description of a smallworker in 1909: “The partner who looks after the mine is his own miner, timberman, mine engineer and blacksmith. On him the mill depends for a constant ten tons of rock each day, which often has to be obtained when he has a shortage of natives. He also has to walk two miles into the bush to see that the gang of native woodcutters are not shirking their duty of supplying firewood for the boiler and cutting suitable timbers for the mine. He has a few head natives who help him in the skilled work and superintend the other native labourers. He starts his work at six in the morning, and is busily engaged until six in the evening, except for a hurried breakfast and lunch. Then he has two hours for dinner and a pipe and at eight o’clock at night he calls out the “night shift” (the natives who work the mine at night) He spends two hours in the mine and leaves the head native to superintend the work for the rest of the night. The other partner takes a day or night shift from six to six at the mill, changing each week with their one white employee. When the partner who has charge of the mill has finished his twelve hours there, he has still all the secretarial work of the partnership to get through, and the mine books to make up, which keeps him busy for another two hours. Such then is the typical life on a mine which has been started with insufficient capital, Sundays and weekdays continuing in unvarying monotony of strenuous work, month after month.”

Evolution of tributor to smallworker

Phimister writes that many smallworkers began as tributors of properties leased from mining companies. “The collapse of the share market in 1903, coupled with inadequate working capital and expensive management, had left many company-owned mining properties financially exhausted.”[xxiii] Tributes on developed properties could be easily obtained with the usual tribute of 10 to 12.5% of the gross value of the gold found, plus the 2.5% royalty to the BSACo.

Then as soon as they could, the profits made from tributing were reinvested in mining claims of their own and at the same time the smallworker searched for quartz reefs: “not with the idea of trying to palm off some useless ground on a mining company, but with the genuine intention of finding a gold reef and proving it for his own benefit.”

Apart from being under-capitalised, many smallworkers were inexperienced miners. Hone wrote in 1909[xxiv] “Of the many small workers…dotted all over Southern Rhodesia, only a few are making tolerable fortunes, some are earning fair profits, but the majority are only just paying expenses.” However in the following years increasing numbers of smallworkers worked as syndicates with the partners each contributing small amounts of capital and gradually their mining experience improved.

How smallworkers paved the way for larger producers and greatly increased in number

In 1909 there were over 500 smallworker producers,, but ironically their numbers began to fall after this date mainly due to their success. Where smallworkers proved their property was a commercial success, they were able to sell out to larger producers. So whereas smallworkers as tributors had previously followed capital, now capital sought out smallworkers! This trend did much to remove the speculative character of gold-mining.

But following the various initiatives taken by the BSACo and as the Rhodesian mining industry improved its productivity and reliability, so new capital for investment entered the country, but in marked contrast to the early days, it source was from South Africa and not the London Stock Exchange.

Sir Percy Fitzpatrick[xxv] wrote in 1907: “There is no Rand here. There is the gravest doubt about depths. Most of the things are small. The average is low. But all about the country individuals are making it pay…The place seems to have a future – not anything startling, but enough in prospect to warrant having a look at it before saying goodbye to South Africa as a field for investment.”[xxvi]

Increasingly capital from South Africa flowed into the country from the major Rand mining houses including Consolidated Goldfields, Eckstein and Company, Lewis and Marks and the Bailey and Albu groups who increasingly bought up mining properties ‘proved’ by smallworkers. These included the Cam and Motor, the Lonely and Shamva Mines.

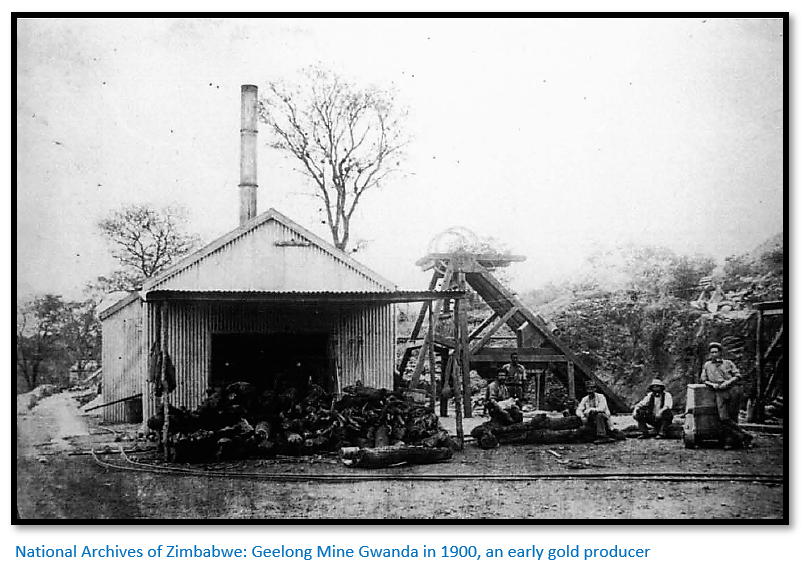

Compared to the initially highly speculative years of 1890-1903 gold production in the period 1904-1912 grew steadily and consistently with output in individual years after 1908 almost equal to total output for the fourteen year period of 1890-1903. The other trend was for the proportion of smallworkers to increase markedly as evidenced by:

(1)39 mines in 1904 utilising 490 stamps (average 12.5 stamps per mine) to 474 mines in 1912 utilising 1,803 stamps (average 3.8 stamps per mine)

(2)39 mines in 1904 employing 9,000 native mineworkers (average 231 per mine) to 474 mines in 1912 employing 34,494 native mineworkers (average 73 per mine)

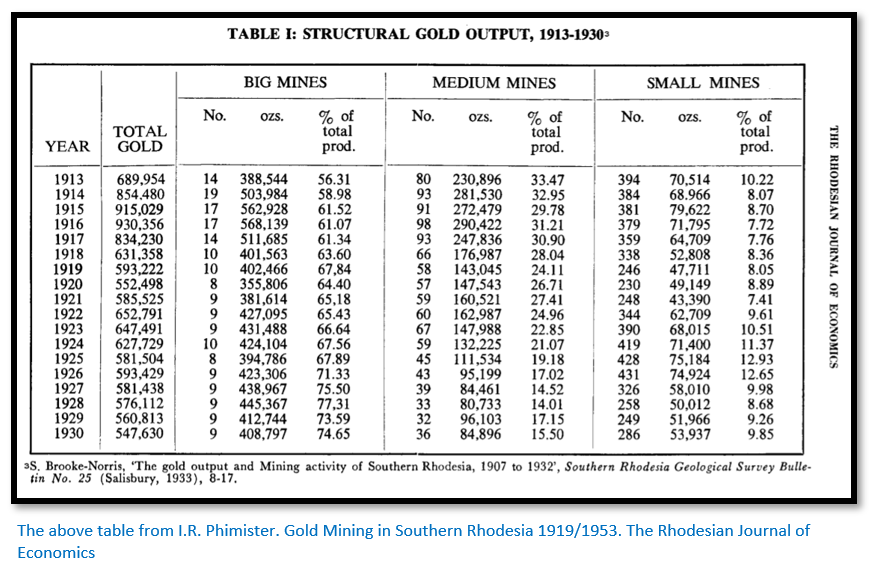

The impact of Smallworkers continued to be influential

Although the number and output of smallworkers between 1919 and 1930 experienced a general decrease in their output and number of producers, it was nowhere near as dramatic a fall as in the medium producer sector. The percentage contribution of smallworkers to the total gold output remained roughly constant at +/- 10% in contrast to that of medium producers which reduced from 33% to 16% as large producers output steadily increased.

Additional Reading

The article in Rhodesiana No 20 July 1969 called Early Days on a Small Working provides a good description of the numerous tasks that needed to be carried out by a smallworker on a gold mine.

References

J.S. Galbraith. Crown and Charter: The Early Years of the British South Africa Company. University of California Press, 1974

P.F. Hone. George Bell, London 1909

HJ Lucas. Early Days on a Small Working. Rhodesiana No 20, July 1969

I.R. Phimister. The Reconstruction of the Southern Rhodesian Gold Mining Industry, 1903-10. The Economic History Review New Series, Vol. 29, No. 3 (August 1976), pp. 465-481

I.R. Phimister. Gold Mining in Southern Rhodesia 1919/1953. The Rhodesian Journal of Economics. Volume 10, No 1. March 1976

F.P. Mennell. Hints on Prospecting for Gold. Rhodesian Publications Limited, 1934

D.A. Mitchell and G.W. Begg. The Gold Mines of Southern Rhodesia; Selected Mining and Postal Histories to 1924. Durban 1996. Photocopy from Rhodesia Study Circle.

[i] By 1900, the BSAC was administering both Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia, and by various means had acquired substantial land and mineral rights. BSAC rule ended in Southern Rhodesia in 1923, when the white settlers were granted responsible government, and in Northern Rhodesia in 1924, when the Colonial Office assumed control. However, the BSAC retained its commercial assets and its mineral rights in Northern Rhodesia became a valuable source of revenue following the development of the copper-mining industry in that territory between the First and Second World Wars. On the eve of Northern Rhodesia's independence, the BSAC was forced, by the threat of expropriation, to assign its mineral rights to the local government. The BSAC merged with two other companies to form Charter Consolidated Limited in 1965.

[ii] Crown and Charter, P278

[iii] Peter Henry Watney attested into the Pioneer Corps on 15 March 1890 as No 25: thus an early member. He was a Trooper in C Troup under Capt J.J. Roach and Lieut E.C. Tyndale-Biscoe. On 27 May [at Macloutsie River Camp he was given three extra 24-hour guards for being absent. On 8 July [at Fort Tuli] he was charged with losing his rifle and fighting in laager. On 28 July [at Lundi river] he was sentenced to pay for the rifle with two extra guards, fined 20/- on the first charge and admonished on the second charge.

By February 1891 he was prospecting near the Marasoti river. Later in business as clearing, forwarding and commission agents in Umtali in 1895 as Gray and Hodgson and later as Hodgson and Watney. Thought to have died of malaria during construction of the Beira-Mashonaland Railway. [Above info all from Robert Cary’s The Pioneer Corps published by Galaxie Press]

[iv] Hints on prospecting for gold, P90

[v] Ibid, P91

[vi] Ibid, P90

[vii] The acting Mining Commissioner signs as J.H. Bowen – possibly a relative of D.J. Bowen the author of Gold Mines of Mashonaland 1890-1980 published by Thompson’s Publications

[viii] There have been a number of ships named the Roslin Castle. The S.S. Roslin Castle which belonged to the Union Castle Mail Steamship Company Limited was a passenger liner with two masts built at the Clyde in 1883 and sailed between London – Cape Town – Lourenco Marques (Maputo) She served in the Boer War as a troopship (HMT 26) and suffered heavy weather damage in 1907 and was subsequently scraped at Genoa [details from http://www.clydeships.co.uk/view.php?ref=1455] Often spoken of as the “rolling castle”

[ix] A.J. Leonard. How we made Rhodesia, Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo

[x] Crown and Charter, P122

[xi] Ibid, P263

[xii] Ibid, P257

[xiii] Ibid, P281

[xiv] The railway extension from Kimberley to Vryburg (126 miles / 203 kms) began in November 1889 and was completed by December 1890. The extension from Vryburg continued gradually through Mafeking, Palapye and Francistown reaching Bulawayo on 19 October 1897.

[xv] Crown and Charter, P282

[xvi] The reconstruction of the Southern Rhodesian Gold Mining Industry, 1903-10, P466

[xvii] Ibid, P467

[xviii] Ibid, P468

[xix] The Gold Mines of Southern Rhodesia, P8

[xx] The reconstruction of the Southern Rhodesian Gold Mining Industry, 1903-10, P465

[xxi] Ibid, P470

[xxii] Ibid, P471

[xxiii] Ibid, P473

[xxiv] Hone, Southern Rhodesia

[xxv] Who write the classic children’s book ‘Jock of the Bushveld’

[xxvi] The reconstruction of the Southern Rhodesian Gold Mining Industry, 1903-10, P479