Zinjanja Monument (formerly Regina Ruins)

- A smaller version of the Danan’ombe and Nalatale Monuments, but also part of the Torwa State which succeeded Great Zimbabwe in the late fifteenth Century.

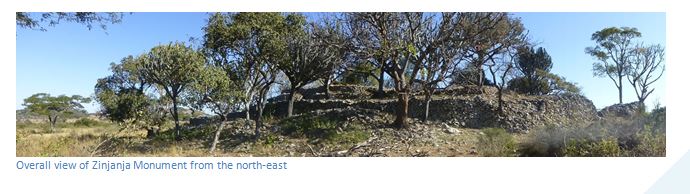

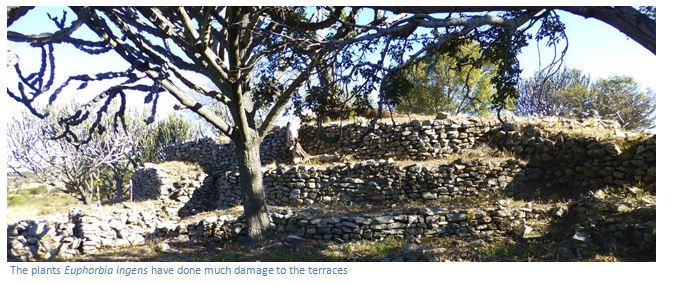

- Zinjanja is further off the beaten track and has not been restored. Much of the dry-stone walling has collapsed over time and some of the terracing, the entrance and the grain bins need restoring.

- Lived in and built for Torwa Rulers; their wealth in cattle attracted the envy of the Rozvi who overthrew them before 1693 and were in their turn overthrown during the Mfecane of the 1830’s during the Nguni invasions.

From Shangani take the A5 towards Bulawayo, 18.4 KM reach Insiza and turn left onto the untarred road heading south-east, 45.8 KM reach Fort Rixon road junction, 46.9 KM turn left towards Fort Rixon, 48.1 KM pass through Fort Rixon, 55 KM turn right at the intersection, 58.2 KM continue on at road intersection, 61.8 KM continue south at road intersection, 65.9 KM turn left at road intersection. [67.6 KM Note: this is the nearest point to the Bertrand and Aleth de Guitaut Memorial 300 metres up the kopje to your left] drive around the base of the kopje, 69.1 KM turn left onto farm track, 71.3 KM reach Zinjanja Monument.

Alternatively drive to Danan’ombe Monument, afterwards continue on the same untarred road going west a further 11 KM to Fort Rixon, then south a further 24 KM to Zinjanja Monument.

Note sign posting to Zinjanja Monument is non-existent, but local people can guide visitors. Don’t take the farm track east from the former Claremont Mine which is shorter, but rough with at least three gates. The route above is better.

GPS reference: 20⁰08′00.02″S 29⁰21′34.98″E

Dr. Hans Sauer in Ex Africa published by Geoffrey Bles in 1937 and reprinted by Books of Rhodesia in 1973 describes how Capt. W. Sampson and B. Bradley and Sauer did a tour of inspection of the Insiza district in 1894 travelling with horses and scotch carts drawn by oxen: and came upon an ancient temple, built by people of whom no record has been left in Africa, or for that matter, elsewhere. We discovered this mysterious building on the 24th of May, the birthday of Queen Victoria and we named it Fort Regina in honour of the Queen. Sauer describes the ruin as an ancient temple, because it was a circular building, with three or four tiers, or circular terraces that reduced in size from top to bottom that were connected by steps. He says the entire structure was built the same way without mortar, or cement, on a large granite dome so that the general shape is of an “enormous round bride’s cake.”

On the second terrace Sauer noticed round flat stones placed at regular intervals and when he turned one over was surprised to see they covered underground holes neatly lined with granite blocks. They lowered a lighted candle tied to an ox riem and found they went down vertically for nearly twenty feet, and by swinging the candle, they established the hole gradually widened as it descended. They tried to guess the purpose of the bottle-shaped holes. Sampson’s suggestion was for storing water, but the water would drain as the slabs were not bound together with mortar or cement; Sauer suggests storing grain, but they speculated it would be impossible to get the grain out again; Bradley thought they were for storing treasure. Roger Summers suggests these and similar structures at Khami and Nalatale may have been latrines, but most archaeologists today believe that the Torwa Rulers levied tributes of grain from the people and this grain, probably millet, was poured through the stone-lined holes into the chambers below.

Bradley, described by Sauer as something of a freebooter, quickly collected a workforce of about seventy local people and constructed a horizontal drive into one of the underground holes, which to their disappointment after two days work, revealed no finds at all except that it rested on granite bedrock. Sauer says he often regretted this act of vandalism. They then trekked north to Danan’ombe, much like Zinjanja, a Type 4 ruin, but considerably larger.

Hall and Neal in The Ancient Ruins of Zimbabwe published by Methuen & Co in 1902 include the Zinjanja Ruin (they call it Regina) as located in Matabeland but their description is short. These ruins are situated three hundred yards north of Meikles’s Store, on the Insiza and Belingwe road, and a few miles south of the Mudnezero Ruins, in the Upper Insiza district. In 1894 they were examined by Dr. H. Sauer, Capt. W. Sampson and B. Bradley and a description was given in the Bulawayo Chronicle. The plan is elliptical, being at the widest points three hundred feet by two hundred feet. There are six tiers of terraces. There are several cellar-like holes under the floors of these buildings. They suggest the bottle-shaped cellars at Zinjanja are merely drains for carrying rain-water from the upper terrace past the lower terraces and so out of the building. However, it appears they never visited Zinjanja, so this comment represents mere speculation. They list the objects found at Zinjanja in 1894 by Dr. H. Sauer, Capt. W. Sampson and B. Bradley as gold beads, gold chains and bangles and smelted gold, plus fifteen ounces (466 grams) of alluvial gold nuggets weighing from one-quarter (8 grams) to half an ounce; also some soapstone objects.

Caton-Thompson’s book Zimbabwe Culture published by Oxford at the Clarendon Press has only a single reference for Zinjanja saying: a similarly constructed mound lies within the mound of Regina Ruins, not many miles away; these structures resemble, on a large scale, the stone hut circles outside the ruins at Matendere.

Roger Summers in Ancient mining in Rhodesia published by the Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia lists the nearby Claremont Mine as having extensive ancient workings comprising open stopes and occasional shafts; the longest stope being 4,500 feet (1,370 metres) and another 880 feet long by 80 feet deep (270 x 24 metres) with large rubble deposits some having gold content of 5.5 pennyweights to the ton (8.5 grams) and an estimated ancient output of 10 – 50,000 ounces (311 – 1,555 kilograms) of gold.

Monuments like Zinjanja close to goldfields strengthened Hall and Neal’s thesis of a link between ancient gold mining and the Monuments that had been developed as forts that protected the gold mining activities and supported their theory of the source of King Solomon’s gold and that the Queen of Sheba’s gold of Ophir came primarily from modern day Zimbabwe.

The archaeological record indicates there is no link in antiquity in Zimbabwe with King Solomon or the Queen of Sheba, but indicates that Zimbabwe was inhabited by Late Stone Age hunter gatherers who painted the rock art found throughout Zimbabwe from about 12,000 to 2,000 BC. Around 2,000 years ago, a new more settled way of life began when Iron-Age migrants entered the country from the north-east, as evidenced in the farming communities at Ziwa and Nyahokwe in the Nyanga area. The earliest state based on cattle rearing seem to have arisen from the Limpopo valley around Mapungubwe and flourished from around 1000 to 1300 AD. At the same time a well-established trade link begun with the East Coast along the Limpopo River which resulted in Mapungubwe developing into a well organised society and the development of a wealthy elite.

On the eventual demise of Mapungubwe, Great Zimbabwe developed into a regional centre and appears to have flourished from about 1300 to 1500 with about 10,000 people settled in the area at its peak and an extensive trade with the East Coast down the Save River. In time internal succession disputes amongst the rulers and possible exhaustion of the soil led to its own gradual downfall.

Great Zimbabwe appears to have been succeeded by two states. One which became Mutapa and centred around Mount Darwin and the Zambezi valley and which became famous through its association with the Portuguese trading for gold through their base at Sofala which they established in 1505 and from their trading posts at Sena and Tete on the Zambezi River.

The other state which succeeded great Zimbabwe was the Torwa state founded around Khame Monument. This part of Matabeland was ideal for cattle rearing, having good grasslands and water and is often marked on old Portuguese maps as Butua. A new type of dry-stone walling structure emerged built as platforms, or tiers on which the ruling elite families lived. The walling is usually decorated, a feature which distinguishes them from earlier walling of the Great Zimbabwe type. The Torwa Rulers lived initially at Khame and then at Zinjanja (Regina) Danan’ombe (Dhlo Dhlo) and Nalatale from approximately 1450 to 1693 AD when envy of their wealth in cattle resulted in their being overthrown by the Rozvi who came from the Mutoko area. Rozvi Chiefs occupied these monuments until the 1830’s, when the Ndebele groups fleeing the Mfecane in South Africa overran the Rozvi, when all of these stone walled communities were largely abandoned as residential sites, although they remained important spiritual sites.

Visitors should not imagine that any of these walls at Zinjanja, Nalatale, Danan’ombe or even Great Zimbabwe were built for defensive purposes. They were built by people ruled by elites who used them to exhibit their power and resources in agriculture and mining rights and large cattle herds. The common people lived around these centres in pole and dhaka houses built much the same as we see today, but over time all trace of their existence has decayed so that only the stone walls remain.

Acknowledgements

G. Caton-Thompson. The Zimbabwe Culture: ruins and reactions. Oxford. 1931

P.S. Garlake. Great Zimbabwe. Thames and Hudson. 1973

R. Summers. Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilizations of Southern Africa. T.V. Bulpin. 1971

R. Summers. Ancient mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia. 1969

H. Sauer. Ex Africa. books of Rhodesia. 1973

R.N. Hall and W.G. Neal. Ancient Ruins of Zimbabwe. Methuen and Co. 1902

R. Burrett and P. Hubbard. Khami, Capital of the Torwa State. Khami Press 2013