Home >

Matabeleland South >

Vere Stent’s recollections of Raaff’s Rangers and the Southern Column in 1893

Vere Stent’s recollections of Raaff’s Rangers and the Southern Column in 1893

Who was Vere Stent?

Vere Palgrave Stent (1872-1941) was a journalist and war correspondent representing the Transvaal Advertiser. After meeting Raaff in September 1893 he was to his surprise appointed as sub-Lieutenant in Raaff’s Rangers and later promoted to Lieutenant and then Captain. Raaff’s Rangers were recruited as part of the British South Africa (BSA) Company’s forces in the Occupation of Matabeleland and in November 1893 joined up with the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) under Lt-Col Goold-Adams, the combined force is usually referred to as the Southern Column.

Officers of the Bechuanaland Border Police (BPP)

Back (L-R) Lieut the Hon D. Martham, Lieut Walford, Dr Vigne, Lieut Wight, Capt Molyneux, Capt Greener

Front (L-R) Capt Browne, Major Grey, Col Sir F. Carrington, Capt Sitwell, Capt the Hon Coventry

In 1896 he represented the Cape Times and Daily Mail during the Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela) and was present at the Battle of Ntaba zika Mambo led by Col Plumer. With the Matabele campaign at a stalemate he was one of the small group that accompanied Rhodes on the dangerous mission that resulted in the Indaba with the amaNdebele Chiefs and peace talks.

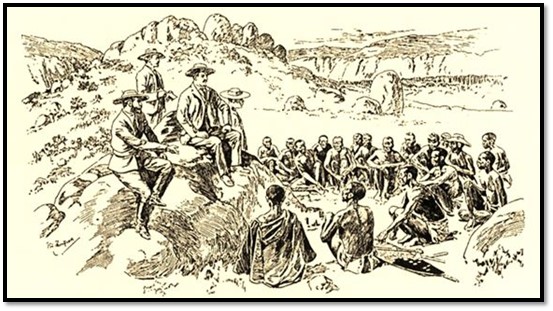

A sketch of the 1896 peace Indaba by Robert Baden Powell who was camped nearby. Vere Stent has his notebook open at the rear

The general background to events

In the introduction to his article in the 1933 Occupation Souvenir celebrated forty years after the Occupation of Matabeleland Vere Stent writes, “the early eighties had seen the opening gambits of a great game of chess between Rhodes and Kruger. They were still playing it in the nineties upon a chequer board of kingdoms, republics and protectorates for squares, with men and women for pawns and presidents and paramount’s, governors, and privy councillors for back-row pieces.”[1]

The Warren Expedition of late 1884/5 to present-day Botswana managed to easily proclaim British sovereignty over the potential grabs of territory from the Transvaal Republic and Germany and also to put down the Boer proclaimed states of Stellaland and Goshen. Rhodes had invented a phrase for that territory to emphasise its strategic value saying, “It is the Suez Canal of South Africa…and must be in our hands”[2] and the bloodless triumph of the Warren Expedition helped ease the tension between the Transvaal Republic and Britain as the limits to Boer expansion now seemed firmly set.

However this was not enough for Rhodes who said, “the future lies in the north. The hinterland must be ours.” Boer encroachments through the Adendorf trek across the Limpopo river were firmly rebuffed; long-held Portuguese claims to Manicaland were denied west of Macequece (present-day Manica)

In 1893 Bulawayo was in commotion

Lobengula regretted signing the Rudd Concession with his chief adviser, Lotshe, put to death for his views. Dreading an invasion of white men into Matabeleland bent on seeking gold, pestered continually by concession-seekers, he was anxious to choose the route least to be feared and surrounded by amaNdebele induna’s who thought in their pride of conquest and blood lust that they were an invincible force. The young warriors (majakas) cried, “We will eat up the white men, let us drive the makewa into the sea.”

So in 1893 at the Great dance or Inxwala Festival[3] Lobengula threw his assegai to the east. He forbade his majakas from killing or interfering with any white men but would not permit the insolent and cattle-thieving Mashona to defy the authority of the Matabele over them. With the great raid of July 1893 the drums of war began to beat.

Raaff begins a recruitment drive

When Pieter Johannes Raaff came initially recruiting to Pretoria and Johannesburg under the transparent disguise of organising an enormous party of prospectors no one worried very much. In reality Dr Jameson did not have enough manpower to keep the road to the south open whilst the Salisbury and Victoria Columns advanced on Matabeleland. The BPP were at their headquarters at Macloutsie in full strength but held in check by the British Foreign Office who refused to get involved in a quarrel which was not theirs and about whose merits they were doubtful.

Raaff continued busy recruiting men and buying horses. Wills and Collingridge in their book Downfall of Lobengula wrote the following about Raaff. “He was a well-known figure throughout South Africa in whose wars he served with bravery and distinction - notably in the Zulu War in 1879, in which he organised and commanded Raaff’s Rangers, being created CMG for his services. He was also offered in recognition of his work a junior commission in one of the native East India Regiments. This, however, he declined. At the close of the Zulu war, Commandant Raaff returned to Pretoria where he was in the British service. When the war with the Boers began, Raaff went down to Potchefstroom and organised the second Raaff’s Rangers, among the loyal residents of the place and ably assisted Sir Marshall Clark in the work of defence. He ultimately went to Mashonaland and was appointed resident magistrate at Fort Tuli. Before the outbreak of the Matabele War, he was commissioned to raise a corps of two hundred and fifty mounted men in the Transvaal. Thus, for the third time, Raaff’s Rangers came into existence, recruited mostly from the mining population of Johannesburg.”[4]

The original plan was for Raaff to raise a commando of Boers, but they were not interested in fighting in Mashonaland or on behalf of the BSA Company.

The tragic event at Tati with Lobengula’s envoys

Lobengula sent a peace mission to Queen Victoria consisting of three Indunas who were brought by James Dawson to the Tati camp of the Southern Column. The Indunas through what appears to have been a genuine misunderstanding were placed under arrest. Goold-Adams had no idea who they were. Certainly no idea they were envoys of peace and unfortunately Dawson did not report them on his arrival. Their arrest shocked the Indunas who suspected treachery, and grew nervous? Mantuse said, “Things look bad for us” and grabbed the bayonet of the sentry standing guard over them and tried to escape with another induna. Both were shot and killed.[5] The third induna was permitted to return to Lobengula, but after that no more was heard of peace. Fairbairn and Usher both told Vere Stent that when Lobengula heard of this event he abandoned all attempts to stop the war. “The white men are fathers of liars” he said bitterly and the majakas rejoiced openly saying, “See, what hope have we of peace but our assegais.”

Vere Stent is recruited and joins Raaff’s Rangers

Vere Stent met Raaff in the lounge of a hotel in Pretoria and asked to be enlisted. That was on Friday 8 September 1893 and the next day he found himself suddenly appointed as a sub-Lieutenant in Raaff’s Rangers! He wrote that he marched from Pretoria with as heterogeneous a collection of human beings as has ever been gathered together even by the trumpet call of war. Most were good men who did well in the new country to which they were going and even the most unpromising did remarkably good work when called upon under discipline and direction. But at the start a more feckless lot it would have been hard to find.

Some, mostly old soldiers, eventually gave a deal of trouble. Others knew nothing and had to be told not to try and make their fires from green newly chopped wood, not to wander out of sight of the camp in case they lose themselves, not to open bully beef tins with an axe. They had to be taught not to shut their eyes when firing their rifles and not to mount a horse with their rifles in the wrong hand. And yet, when it came to fighting, they did nothing to disgrace themselves and faced the perils and hardships with the very best of the other troops.

Raaff’s Rangers march to Fort Tuli

Vere Stent writes the march was better-suited to comic opera than the tragedy of war. His force varied from as few as thirty to as many as one hundred men and his orders were to get to Fort Tuli as soon as possible with as many men as he could persuade, order, control, entice or bribe. The march took just under a month and they arrived at Fort Tuli on 3 October 1893 marching, as he says, as quite a respectable looking Troop. After Pietersburg most had exhausted their money and Stent’s threat to turn any adrift who gave trouble became effective.

A few miles from the Transvaal border they came across one of those wayside stores which had sprung up along the road to the north. The storekeeper thought he saw an opportunity of making a good profit and tripled the price of liquor. The men appealed to Stent, but he was powerless to regulate prices and they trekked two miles beyond the store in order to start next day before daybreak in the hope of crossing the Limpopo river the next morning. Dawn broke, the natives inspanned the two wagons and they stepped out at a very quick march to the tune of ‘With my bundle on my shoulder’[6] and by evening were safe across the river which was just as well as a patrol of Staats Artillerie were hot on their heels. It turned out that the men had arrived at the store after dark taking liquor and signing IOU’s for payment whilst the storekeeper had stood by helplessly!

Attested by the BSA Company at Fort Tuli

The Troop were then attested under the BSA Company’s police ordinance. A march of 125 miles (200 kms) took them to Macloutsie where they joined forces with the BBP becoming the Southern Column, although they liked to refer to themselves as the Imperial Column.

The Southern Column moves out of Macloutsie

The Southern Column under Lt-Col H. Goold-Adams left Macloutsie without much delay on 11 October 1893. The force strength was 225 Officers and men of the BBP with four Maxims and two seven-pounders, fourteen wagons and fifty native drivers accompanied by 230 Officers and men of Raaff’s Rangers with one Maxim and eleven wagons.

At the Shashe river they were joined by Khama III’s men comprised of 130 mounted men and between 1,700 – 1,800 foot soldiers, about half of whom were armed with Martini-Henry rifles. Tati was reached on the 19 October, but the water supplies there were insufficient for the number of men, horses and oxen.

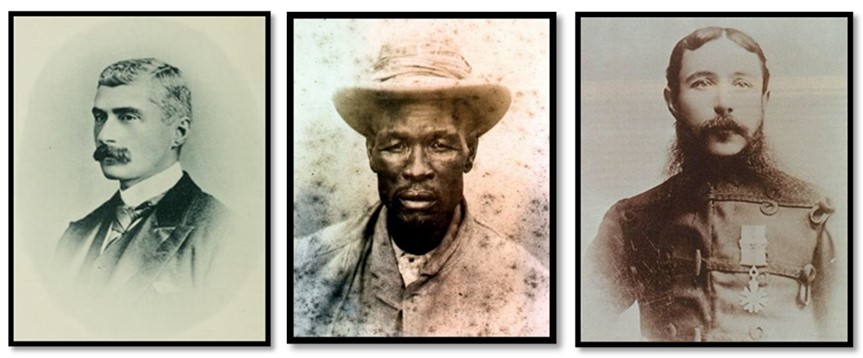

Lt-Col Hamilton Goold-Adams Khama III Commandant Pieter Johannes Raaff

The water problem made the combined force spread out and Raaff’s opinion was, “It was then a straggling force that entered Matabeleland from the south and had Gambo been any sort of general, with any sort of disciplined army, he ought to have been able to take us in detail and - with the numbers at his disposal to destroy us without difficulty.”[7]

A number of sources state Gambo had 8,000 men under his command. (Wills and Collingridge, P215) and their were two amaNdebele impis in the vicinity – one at the Simukwe river 35 kms to the east and another at Khosingnana at the north-eastern edge of the Matobo Hills.

The advance on Bulawayo

Raaff continues, “Truth to tell the prowess of the Matabele was vastly overrated. Lobengula, amiable, easy-going, weak, driven indeed by every wind of public opinion, that blew about him was no Chaka (Shaka Zulu) or Umzeligazi (Mzilikazi) no, not even Cetewayo (Cetshwayo) and his impi’s were ill disciplined and having had no one worthy of their steel to fight for so long, were not the sort of shock troops that alone could have prevailed against our laagers.”[8]

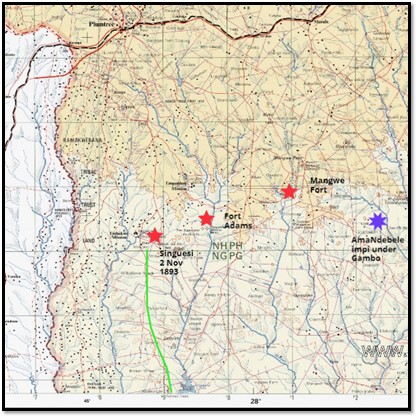

He says that at Imbandine (Empandeni) was fought the only battle with the amaNdebele of any significance. This is described in some detail in the article The Southern Column’s skirmish at the Singuesi river on 2 November 1893 revisited under Matabeleland South Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Vere Stent’s account of the Singuesi river skirmish in the Transvaal Advertiser

Just in time for a hurried dispatch account of our first engagement. At 9 o’clock today, the main camp was alarmed by the sound of heavy firing in the rear, proceeding, no doubt, from the baggage train moving to join us. In less than ten minutes from the sounding of the alarm, three troops of Raaff’s Horse, under Raaff himself were moving out at a gallop, to the rescue, with two troops of the BBP, leaving the infantry to guard the camp. Hardly had they disappeared before the Maxims rang out, telling of hot work in the distance. Three minutes later and the leading wagon was greeted with cheers. Close after them came out mounted men, hard pressed by a horde of yelling fiends.

Map 1 – adapted from 1:250,000 map sheet SF-35-3 Plumtree; this map is used with consent from Window on Rhodesia with the site name: https://www.rhodesia.me.uk

A moment's confusion followed, while the horses were being got into laager and men were beginning to look anxious, when, from the South face came again the roar of the Maxim. The effect was magical and the loud cheers that followed told of the confused retreat of the enemy, awed and beaten back by that most deadly of instruments. Upon the retreat of the enemy into the surrounding kopjes, the mounted men again moved forward to the rescue of the remaining wagons, from which still came heavy firing. A half hours rapid work and the enemy were forced to give up their booty, so dearly bought, not however, before they had managed to set fire to and destroy one wagon of the BBP.

Fighting was now confined to attacking the kopjes occupied by the enemy. Here the seven-pounders were of great use, dropping shell after shell among the scattered and hard-driven Matabele who were rallying in the rear of the surrounding hills. At this point in the engagement Colonel Goold-Adams and staff commenced sharp-shooting from the wagons with considerable success considering the distance (1,000 yards) Khama’s Maruda Regiment did some magnificent fighting on the flank, pouring a resolute fire into the brown of the enemy. The Mapashales acted as a reserve and did not engage. So hot was the engagement that, at one time, a Maxim gunner was seen firing the gun with his left hand and his revolver with his right. The killing of a chief was the signal for a rush for his shield, while to fall, even slightly wounded was death. Without any doubt, this preliminary skirmish has taught the far-famed Matabele that the end of their long-lived power is at hand, and they will fight with the courage of desperation. The loss of the enemy is estimated at from two hundred to five hundred. In one cave alone, twenty-eight were found dead. The men behaved splendidly and both Raaff and Goold-Adams are to be congratulated on our first success. There is no time to give a more detailed account of the battle: would that it were possible to give instances of individual bravery and heroism: but your readers must be content with this hurried account written upon the seat of a Maxim.

Raaff’s postscript to Vere Stent’s article

Raaff makes fun of Stent’s ‘upon the seat of a Maxim’ and says that he heard that Goold-Adams had not fired a shot!

He gives those killed as Troop Sergeant-Major Dahm and Corporal Mundy who were attacked on the wagons and three of Khama’s men and six or seven wounded. He estimates the amaNdebele killed as about sixty and an unknown number wounded.

The most significant result was that Gambo reined in his forces and took almost no further activity in the rebellion.

Reference

Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir. November 1933

Notes

[1] Occupation Souvenir, P31

[2] The missionary road from Kuruman went north through present-day Botswana

[3] See the article The Great Dance or Inxwala Festival under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[4] W.A. Wills and L.T. Collingridge. The Downfall of Lobengula. Books of Rhodesia Gold Series Vol 17, Bulawayo 1971

[5] A detailed account is contained in Appendix 2: the shooting of the amaNdebele envoys in the article The Southern Column’s skirmish at the Singuesi river on 2 November 1893 revisited under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[6] The American Civil War song goes:

He’s gone to be a soldier,

With a knapsack on his back,

A fightin’ for the Union

And a livin’ on “hard tack”

Oh how he look’d like Christian,

In the Pilgrim’s Progress shown,

With a bundle on his shoulders

But with nothin’ of his own.

[7] 1893 Occupation Souvenir, P34

[8] This seems an unfair comment from Raaff as attacking the laagers would have meant attacking in the face of Maxim guns. This the crack Regiments of the amaNdebele did at Shangani (Bonko) and at Bembesi (Egodade) and suffered huge casualties from the machine-gun fire

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: