Selous House (near Esigodini)

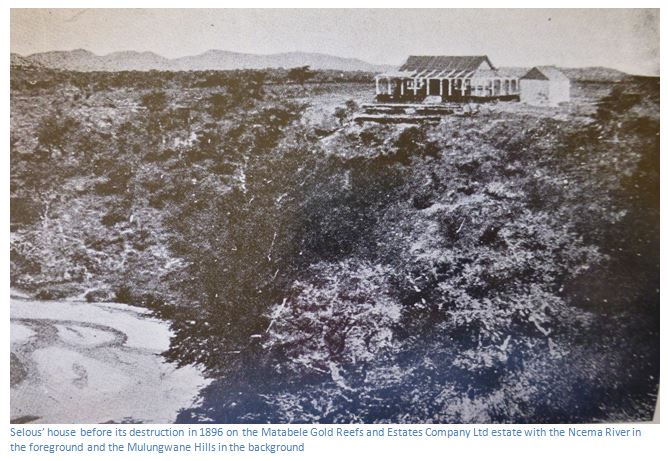

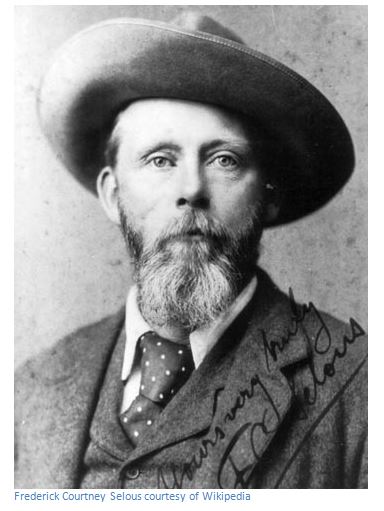

Probably the best personal account of the Matabele uprising or First Umvukela is by Frederick Courtney Selous in his book Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia. This contains a detailed account of the early days of the uprising with many references to his house on the Ncema River. For this reason alone, the foundations of the house are historically relevant and interesting.

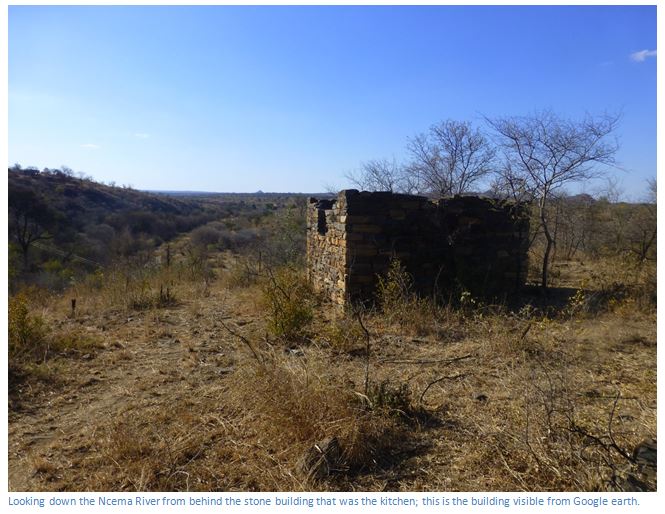

The isolated homestead of Fred and Marie Selous must have enjoyed the company of many prominent visitors who made the journey of a good days ride by horseback from Bulawayo to their ranch headquarters on the Ncema River. Today just the foundations of the original terraces, the stone walls of an outhouse and the views down the river remind us of its origins. In the background the constant sound of the single stamp mill at the Eureka gold mine and further away those of the Eveline gold mine disturb the profound silence of the Matabeland countryside.

Wire-wove houses were an early form of prefabricated buildings which were manufactured on an assembly line in Britain and shipped out to the colonies and could be transported to their final destination by ox-wagon before being rapidly assembled by semi-skilled labour.

Take the road from Esigodini to Falcon College. At 4.8 KM cross the Ncema River Bridge, 10.3 KM arrive at Falcon College entrance.

From Falcon College entrance, turn left and take the road going northeast, at 0.5 KM continue straight on and do not turn left. Follow the road across a spruit and at 3.0 KM take the right fork just before the Ncema River. Cross the river and take the right fork just after. Drive 700 metres around a gentle left bend, with the river bending left and then right. The small stone building and foundations are 30 metres from the road and 60 metres from the river bank in the narrowest section between road and river and the homestead faces up a long straight stretch of the Ncema River.

GPS reference: 20⁰11′26.92″S 28⁰55′52.28″E

Amongst the most renowned of the big game hunters including Baldwin, Cumming, Finaughty, Hartley, Lee, Oswell, Van Rooyen and Viljoen, was Fredrick Courtney Selous who arrived in this country in 1872 at the age of 19. He received permission from Lobengula to hunt elephant and explored, hunted and traded for the next eight years in Matabeland and Mashonaland. Others shot more elephants than Selous, but nobody left better written records than he did in his books A Hunter’s wanderings in Africa published in 1881 and Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa published in 1893. He wrote six major books and many articles for the Royal Geographical Society and other institutions. Although he initially hunted for ivory, he later made collections of animals, birds, birds’ eggs and butterflies for museums in England and America.

Even as he arrived the ivory trade was in decline, the elephant had retreated into the mopane forest where the dreaded tsetse fly was found and it became no longer possible to hunt on horseback. For this reason the old hunters like Finaughty had given up, but Selous was prepared to hunt on foot, a much more dangerous proposition, in his efforts to pursue the elephant, and it was this that made his hunting reputation.

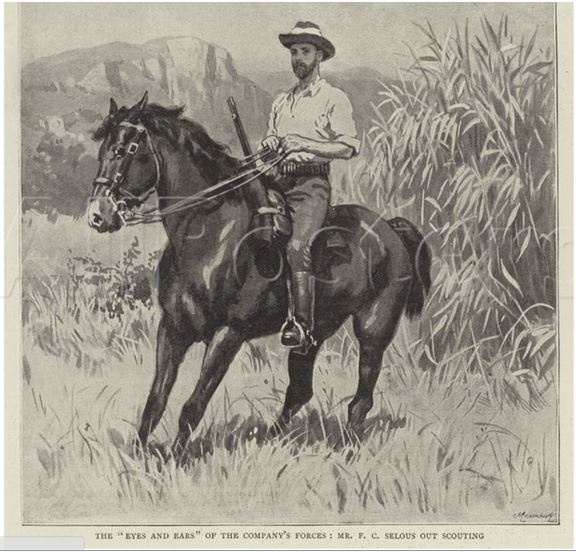

As the Intelligence Officer he was Rhodes’ choice to cut the road for the Pioneer Column from Macloutsie in modern day Botswana to Mount Hampden in Mashonaland in September 1890, a distance of 736 kilometres. He helped bring Manicaland under the control of the BSA Company and cut the road to Umtali (now Mutare) which was called the Selous Road in most contemporary accounts. Many of these interesting times are described in Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa.

He served in the First Matabele War (1893), and was wounded during the advance on Bulawayo. One of his fellow scouts was Frederick Russell Burnham, who had only just arrived in Africa, and they observed the self-destruction of the Ndebele settlement at Bulawayo as ordered by King Lobengula.

Selous returned to England, married, and in 1895 was appointed to manage a land and mining company in Essexvale (now Esigodini) in Matabeleland, when the Second Matabele War broke out. The outline of the remaining storeroom and adjacent foundations of this house can be viewed on Google Earth at 20°11′27.49″S 28°55′53.18″E approximately 30 metres north of the track and perched 25 metres above the Ncema River.

He was in this post when the Matabele uprising or First Umvukela broke out in March 1896 and after escorting his wife to Bulawayo took command of H Troop of the Bulawayo Field Force and also Fort Marquand and took a prominent part in the fighting which followed, and it was during this time that he met and fought alongside Robert Baden-Powell who was then a Major and newly appointed to the British Army headquarters staff in Matabeleland.

Essexvale was founded in 1894 and during 1895 Selous was appointed as manager of an estate of nearly 200,000 acres. In the National Archives of Zimbabwe are some notes written by his wife Marie in which she describes their departure from England on 30 March 1895; two months spent at Rhodes’ home in Cape Town who gave them £500, the journey to Rhodesia via Beira, their arrival in Bulawayo. They begin work on the company estate of at Essexvale growing maize, vegetables and timber. Their first home is a two roomed pole and dhaka hut, until the wire-wove bungalow, which had been sent out from England in sections, arrived and could be erected.

Marie describes the forty acres that were ploughed, 5,000 trees planted, mainly Eucalyptus, 1,000 head of cattle. She made 8 – 12 pounds of butter a week with the help of a servant. There were two other European staff employees; she describes the events around the Matabele Uprising, their flight to Bulawayo and the hardships encountered within the Bulawayo laager and finding their home destroyed on their return to Essexvale.

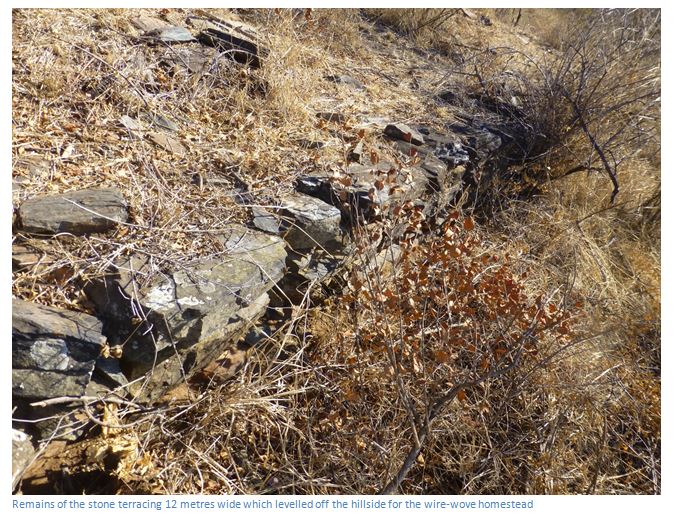

Fred Selous erected the wire-wove house featured in the photo below on top of the cliff 25 metres above the Ncema River after levelling the ground with a series of twelve metre wide terraces supported by stone. I counted the remains of five such terraces in 2016.

During the Matabeleland Rebellion of 1896, Selous left the estate and assisted in quashing the rising, but during his absence the house was burnt down by Inxnogan, one of the rebellious Matabele indunas. When the Rebellion was over, he wrote a book of his experiences, entitled Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia and retired to England.

In 1914, at 60 years old, he volunteered for service and after some reservations due to his age, was appointed a Captain in the Royal Fusiliers serving as an Intelligence Officer in East Africa. He received the DSO in 1916 for “conspicuous gallantry, resource and endurance,” but was sadly killed in action by a German sniper at Behobeho, now in the Selous Game Reserve in south eastern Tanzania, on 4th January 1917, aged 65 years.

Selous says that September and October 1895 were intensely hot, but that their well-thatched house was much cooler than any in Bulawayo, that seat of light and learning to which they paid occasional visits. The wire-wove house arrived in late November as the rainy season was starting and after the site had been levelled and terraced was only ready by late December. This was on the site Selous had chosen at the top of a cliff, 25 metres above the Ncema River; he calls it the Ingnaima River.

Here they lived the first three months of 1896 happy and contented, and he says, apparently on friendly terms with all the natives living around them. His company bought 1,200 cattle and distributed them around in lots of ten to thirty for herding, in return for the milk. He was assisted in the estate management by a young German, Herr Blöcker, who was the forest officer on the estate. It was the Company's intention to raise large quantities of gum trees for mining purposes and they planted 5,000 trees on eight acres behind the house. Another thirty-two acres were ploughed for maize, with an acre near the house for vegetables.

Flower beds were laid by his wife around the house, orange and other fruit trees planted and several banana and granadilla plants from the Rev. Helm at Hope Fountain Mission were growing well. The view from their front door showed cattle and horses grazing on the river banks and ducks and geese swimming in the river itself, and Selous describes it as “singularly homelike.”

Chief Umlugulu lived about 25 kilometres away and often visited and was always treated by Selous and his wife with respect as a man of importance; but Selous would remember how he questioned Selous closely on the details of the Jameson raid after Jameson has taken almost all of the BSA Police force with him out of the country.

There were vague rumours of an Ndebele uprising, but nothing substantive enough to take action. Native commissioner Jackson about 20 kilometres away past Esigodini heard rumours of a coming disaster to the white man emanating from the “Mlimo” who lived in the Matobo; the evidence had been a total eclipse of the moon shortly before. The people were told that Lobengula was not dead and would return to liberate them with a large army. None of those with long experience of the Ndebele…native commissioners, missionaries, traders and hunters had heard rumours of an uprising, with the exception of Mr Usher, a long-time resident trader who steadfastly maintained the Ndebele would one day rise.

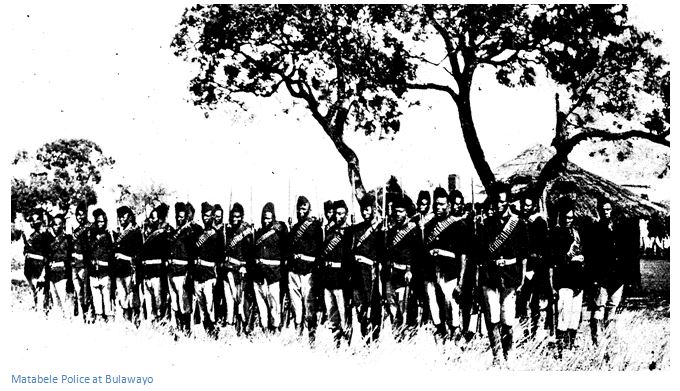

Selous says he had many conversations with native commissioner Jackson on the subject, but came to the conclusion there would be no revolt until Lobengula appeared with his army. However Jackson did say: “it is very difficult to worm a secret out of a native, and if there should be an insurrection those are the devils we have to fear,” pointing to his squad of native Matabele policeman, sitting around their huts all armed with repeating Winchester rifles. When the Ndebele uprising, or first Umvukela came about in March 1896 Selous estimates about half the native police deserted with their rifles.

Selous felt that Chief Umlugulu and members of Lobengula’s family and the Indunas thought their opportunity had arrived when they heard that almost the entire BSA Police force with Jameson, together with most of the Maxims which had been stored in Bulawayo, were now captured by the Boers.

About the middle of March 1896, with the arrival of the rinderpest from the north, Selous was appointed a cattle inspector for the area between the Umzingwane and Insiza Rivers. All movement of cattle was halted, except for the wagons bringing food into Bulawayo whilst there were still cattle to pull them.

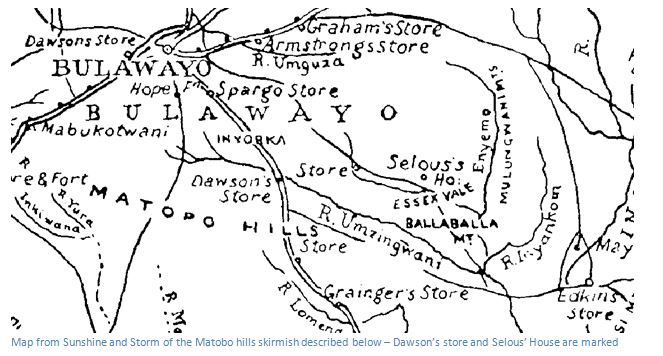

On Sunday 22nd March he arrived in Bulawayo late in the evening having been inspecting cattle and heard rumours of a disturbance between Native Commissioner Jackson’s police and a Matabele kraal near the northwest boundary of his company’s property. Next day he rode forty kilometres down the Tuli road to Dawson’s store on the Mzingwane River and learnt from Jackson that a native policeman had been murdered on Friday 20th March and those responsible had fled into the Matobo hills with their families and cattle.

When Jackson arrived at Umgorshwini, near the Mzingwane River, they heard that headman Umzobo had provoked the police by toy-toying in front of them in a provocative way and frequently saying “you’re killing us” to mean “you are making life unpleasant to us by enforcing the [BSA] Company’s laws.” The defiance continued until the police suddenly saw an armed man creeping behind them. They quickly disarmed him and were putting on handcuffs when a shot was fired, but instead of hitting the police, it killed their prisoner. Umzobo and his men disappeared, but gunshots fired at them killed a blanket-carrier and a small boy of twelve was found dead next day by Jackson and his men.

Selous felt that Chief Umlugulu and members of Lobengula’s family and the Indunas thought their opportunity had arrived when they heard that almost the entire BSA Police force with Jameson, together with most of the Maxims which had been stored in Bulawayo, were now captured by the Boers.

About the middle of March 1896, with the arrival of the rinderpest from the north, Selous was appointed a cattle inspector for the area between the Umzingwane and Insiza Rivers. All movement of cattle was halted, except for the wagons bringing food into Bulawayo whilst there were still cattle to pull them.

On Sunday 22nd March he arrived in Bulawayo late in the evening having been inspecting cattle and heard rumours of a disturbance between Native Commissioner Jackson’s police and a Matabele kraal near the northwest boundary of his company’s property. Next day he rode forty kilometres down the Tuli road to Dawson’s store on the Mzingwane River and learnt from Jackson that a native policeman had been murdered on Friday 20th March and those responsible had fled into the Matobo hills with their families and cattle.

When Jackson arrived at Umgorshwini, near the Mzingwane River, they heard that headman Umzobo had provoked the police by toy-toying in front of them in a provocative way and frequently saying “you’re killing us” to mean “you are making life unpleasant to us by enforcing the [BSA] Company’s laws.” The defiance continued until the police suddenly saw an armed man creeping behind them. They quickly disarmed him and were putting on handcuffs when a shot was fired, but instead of hitting the police, it killed their prisoner. Umzobo and his men disappeared, but gunshots fired at them killed a blanket-carrier and a small boy of twelve was found dead next day by Jackson and his men.

One of Umzobo’s men, Ganyana, went to the kraal of Lobengula’s nephew, Umfondisi and called out; “come Umfondisi, why are you sleeping? Don’t you know we’re fighting, we’ve killed some policemen, come; blood is running and men are lying dead; come with me and let us do some more killing.” They then went to a neighbouring kraal and killed one of Jackson’s policemen.

On Tuesday 23rd March, Selous rode through Umgorshwini and saw the bloodstains himself, although the kraal was deserted. He reached his homestead on the Ncema River about midday to greet his wife, Herr Blöcker and a young Scotsman, Mr Notman, who occupied some huts close by.

His wife told him several men had come over from the Intuntini kraal and requested axes to strengthen their cattle kraals. These they were given and sharpened on the grindstone and Selous believed they had come with the intention of killing, but finding Selous absent and Herr Blöcker with a rifle going to shoot a cow which had dislocated her hip, they had left.

George, one of Selous’ servants came and told him his wife, a Matabele woman, had heard white men had been murdered on the other side of the Mulungwane hills, including a native commissioner whose throat was cut by his native police. This was Mr Bentley, killed whilst writing in his hut, the date above his entry being Monday 23rd March 1896, near Edkins store, Filabusi. Selous now realised that the native uprising had begun, although he still believed that local people would not murder them as he and his wife had assisted them. He told Herr Blöcker and Mr Notman to keep their rifles handy and he stayed awake all night with his rifle and cartridge belt beside him.

That same night all the cattle were taken and Alex Anderson, Charles Percy Eagleson and Wilson Forster, all carrying out mining work within the Esigodini / Mawabeni area, were killed.

The next morning Thursday 25th March, he asked George if his wife had more details of the killings and was just starting breakfast when George ran back to the house and shouted at the stable-lad to bring the horses. Selous feared an attack, before George told him all the cattle had been stolen by Ndebele armed with guns and assegais and everyone from the Intuntini kraal had left for the Mulungwane hills.

Selous decided the first thing to do was to take his wife into the safety of Bulawayo, the horses were saddled up and George posted as a vedette on a rise behind the house from which there is a good view of the surrounding countryside. He then spoke to Headmen Umsetchi, whose kraal was near the house saying after leaving his wife in Bulawayo he would return with an armed force to recover the company cattle.

On their way into Bulawayo they met Messrs Norton and Edmonds and Claude Grenfell who were bringing a cart and horses to bring in Mrs Selous. Grenfell did not know at this time that his brother, Pascoe St. Leger Grenfell was killed near Ingwenya Fort northwest of Gweru the same day. [See the articles on the website www.zimfieldguide.com relating to the Gweru Memorial (Matabele uprising, or First Umvukela, 1896) and Fort Ingwenya and cemetery]

Selous left his wife with Mrs Spreckley, but found the BSA Company could only supply six spare horses and twenty rifles. So with thirty private horses and some private rifles, he managed to get together a force of thirty-six mounted men and leave Bulawayo two hours after sunset.

The moon was full and with its light they rode back to Selous house which they reached at 2am on Thursday 26th March. Here they found George with some of Umsetchi’s men installed in the stone stable. At daybreak a local Headman, Inshlupo, turned up and said the company’s cattle had been stolen the previous evening by armed men.

Selous and his men immediately saddled up and with the guidance of Inshlupo reached the first kraal where they thought they might find stolen cattle. Only the Headman’s wife was present, and so after sending the recaptured cattle back to his homestead, he had the kraal burnt down and rode across to the Mulungwane hills. As they climbed up the hills, the slopes became more heavily wooded and they spotted cattle tracks.

Around 9am they were having a rest when a sentry reported cattle being driven up a valley to their left. They saddled up and rode up a parallel valley and on cresting the ridge of the Mulungwane hills saw cattle and herders below them. Upon opening fire, the herders dropped everything and ran away. Chasing them turned out a fruitless exercise on the steep slopes, but they did find another herd, making a total of around 150 recovered cattle, many with Johan Colenbrander’s brand on them.

Both horses and men were tired by the time they arrived back at Selous homestead in the afternoon. The 500 head of cattle had to be left at the homestead because they could not be sent in Bulawayo with the rinderpest outbreak, but Selous realised they made rich bait. Sure enough ten days later, Inxnozan, a local headman, descended upon the Selous homestead with 300 men and burnt down the house and stables and all the storehouses taking off everything they could carry and all the cattle.

Next day Friday 27th March Selous and his patrol made a start for Jackson’s police camp at Mawabeni (Selous calls it Makupikupeni) passing and setting alight the Intuntini kraal and reaching their destination at about midnight. The camp had been hastily evacuated leaving personal possessions such as coats, hats and blankets behind. They subsequently learnt that Col. Spreckley’s patrol had reached the Mawabeni camp on Wednesday night when they were occupied by seven police constables and a sergeant who immediately fled taking their arms and ammunition.

At Mawabeni camp they heard a rumour that the police had mutinied and murdered Jackson and their officers in the Matobo hills and Selous decided to make for Spiro’s store, on the main road from Bulawayo to Tuli, and on the edge of the Matobo hills. There seems to be a strong case for Spiro’s store being at modern day Esibomvu. It sits at the crossroads of the road to Hope Fountain Mission and the old road crossing the Mzingwane River. On the summit of the ridge which led down to the, it would have been at an ideal point to change the tired coach mules after the long pull up from the Mzingwane River and is also on the eastern edge of the Matobo hills. Selous says it was nearly 20 kilometres from Mawabeni, but he may have guessed, in fact it is nearer 12 kilometres.

It was Saturday 28th March and Selous called his patrol together and asked for volunteers saying the countryside was rough and they would have to walk and lead their horses most of the way. Nobody wanted to be left behind and all volunteered. Mazhlabanyan, a Matabele of Makalaka descent, who had fought and been wounded at the Bembezi Battle of 1893, was their guide and they reached Spiro’s store before sundown finding just the stable lads in charge of the coach mules present. They slept the night under the Store’s verandah before setting off into the Matobo hills.

Herr Blöcker, Simms and Fletcher acted as scouts as they made their way up a valley, and Simms made the first sighting of armed men. The valley up which they advanced was wide at first but gradually narrowed and they began to hear voices shouting from the hilltops. As they entered the narrow and rocky neck of the gorge, shots were fired from behind and as they crossed a stream armed men were seen in front and a skirmish began. The patrol advanced steadily until they suddenly came across a kraal, filled with cattle, at the base of a rocky kopje.

They scaled the rocks and Selous had a narrow escape when he walked around a rock to find an armed man a few metres below him. Both fired simultaneously, but both shots missed, and his assailant disappeared. Having posted sentries, they tried to drive the cattle away, but they refused to be driven and shots began to come from the surrounding kopjes. Herr Blöcker and other good shots returned fire from the stream and Selous and Claude Grenfell protected their rear, but before they entered open country four horses had been killed and Stracey and Munzberg wounded; Stacey through the knee and Munzberg incurred a deep flesh wound in his back. There were many narrow shaves, including the sergeant major with two bullets through his gaiters and one through his trousers, but without being wounded.

Herr Blocker with half the troop ahead, Selous, Grenfell and the others continued to protect their rear and prevented their assailants from following them from the hills into the open ground. Selous believed many were former native police as they wore their white knickerbocker trousers of the police uniform. They also used police-issue Winchester rifles and shot accurately.

What Selous learned from this encounter was that the horses were simply a nuisance amongst the granite boulders and all subsequent fighting would have to be done on foot.

After an hour’s rest they made straight across country to Dawson’s store, on the Mzingwane River drift and twenty-five miles from Bulawayo. Mr Boyce, in charge of the store, was advised to pack up and join them into Bulawayo which he did. They left at sundown, reaching the post station, twelve miles from Bulawayo soon after midnight and lay down in the mule stable, where they all got soaked in the heavy rain. By midday they were in Bulawayo. It was in the course of this journey into Bulawayo that Boyce told Selous the circumstances of O’Connor’s escape from the Celtic Mine near Filabusi. [See the story of Edkins store and the Filabusi Memorial on www.zimfieldguide.com] Selous was delighted to find his friend native commissioner Jackson alive and well in Bulawayo.

Selous says he rode with Col. Napier’s Gwelo patrol through the Insiza district visiting the farms where the Fourie and Ross families were murdered in late March. They buried the bodies of nine women and children, next to the bodies of Troopers A. Parker and G. Rothman (the ’96 Rebellions spells his name as Rootman) but could not find those of Messrs C.H. Fourie and J. Ross, and burnt a large number of kraals in the Insiza valley and took as much grain as they could carry. Soon after reaching the Bulawayo – Belingwe road they met up with Col. Spreckley’s column who were similarly burning kraals and had found the bodies of a miner named R. Gracey, Dr and Mrs Langford and R.J. Leman. [All these names are listed on the Pongo Memorial which is on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The same day a patrol under Gifford left for Filabusi and the site of the Edkins store massacre. The remainder returned to Bulawayo and as the road passed north of his company’s property Selous was given permission to visit his homestead with Herr Blöcker. After two hours ride they reached their destination: “only to find that the house was absolutely gone, literally burnt to ashes, there being nothing left to mark the spot on which our pretty cottage had once stood, but the stone pillars and solid iron shoes on which it had rested. The roof of the stable had been burnt too, as well as all the outhouses, and a waggon, under which wood must have been piled in order to set it alight. The only building which had not been destroyed was the kitchen, which had been built very solidly of stone with an iron roof and was practically fireproof. The mowing machine and rake had not been touched, nor had the ploughs been interfered with. In the vegetable garden we found any amount of cabbages, cauliflowers, onions, carrots, parsnips, beetroot and tomatoes which had ripened since the natives had left and we loaded up our horses with as much as they could carry.”

Some of the major causes of the Matabele uprising, or First Umvukela

One of the Matabele grievances and undoubtedly a major cause of the Matabele uprising or First Umvukela was the question of land and cattle. When the Imbizo, Insuga and Ingubo Ndebele regimental leaders surrendered on 9th April 1894, Jameson told them they were required to surrender the King’s cattle and their Indunas and headmen would remain as leaders and would be allowed to go back to their ancestral lands, but only as tenants without any legal right to it, and therefore subject to summary evictions.

As tenants they would be expected to pay rent in the form of labour on the farms and in the mines and in later years every married man would be required to pay hut tax for every wife’s hut.

On 24th May 1894 an agreement was signed in London between the BSA Company and the British Government concerning the government of Matabeleland and Mashonaland and was enacted in the Matabeleland Order-In-Council of 18th July 1894.

Besides various administrative, legislative and judicial provisions, the Matabeleland Order-In-Council contained certain clauses to protect the indigenous people’s rights including the setting up of a Land Commission to: “assign, without delay to the natives, inhabiting Matabeleland land sufficient for their occupation, whether as tribes or portions of tribes and suitable for their agricultural and pastoral requirements including in all cases a fair and equitable proportion of springs or permanent water.” The Land Commission was also “to direct the Administrator to deliver to the indigenous people “cattle sufficient for their needs”, and that the official was to comply.”

The major trouble to the implementation of these clauses was that by this time the European volunteers in the 1893 war had already finished pegging their farms! By February 1894, the whole southern Matabeleland, including Essexvale (Esigodini) and Matopo Hills were declared “occupied” and by August 1895, there were 1,400 European farms of 3,000 morgen each (2,570 hectares) within the Bulawayo District and mostly within a 60-mile (96.5 km) radius of Bulawayo.

The main beneficiaries of the Matabeleland land-grab after Lobengula had fled Bulawayo in 1893 were Maurice Heany, Hans Sauer and Arthur Rhodes, a younger brother of Cecil Rhodes. Together, they held 452,000 acres (182,918 hectares) of land in southern Matabeleland. Maurice Heany was a director and joint manager with Selous of the Matabele Gold Reefs and Estates Company Ltd, which by 1895 had a total land-holding of 221,000 acres (89,436 hectares) of land, plus 773 gold claims and 1,200 Ndebele “loot” cattle and which had originated from a syndicate formed by Maurice Heany after the occupation of Bulawayo.

Hans Sauer managed the Mashonaland Development and Exploration Syndicate Ltd in the same Essexvale (Esigodini) area and had four large blocks of land, one of which was Sauerdale, which was quickly disposed to Rhodes. Sauerdale comprised 181,000 acres (73,248 hectares) of land and held 1,200 of “loot” cattle under the management of Arthur Rhodes.

Another large expropriation of land was the 600,000 acres (242,811 hectares) that was granted to Sir John Willoughby in the Gweru area, known as Central estates.

The BSA Company’s opinion was that all cattle in the whole of Matabeleland were Lobengula’s cattle and therefore became company property through the 1893 conquest. A “Loot” Committee consisting of Captain Heyman (Chairman), Christison (Mining Commissioner and BSA Company nominee) and Sampson (the volunteers’ nominee) was formed at the end of March 1894, under provisions of the 1893 Victoria Agreement, under which the volunteers signed on.

By mid-March 1894 more than 30,000 Ndebele ‘loot’ cattle had been surrendered and the Committee had to determine how many cattle the volunteers were entitled to under the Victoria Agreement.

Of the 30 000 “loot” cattle, 25, 000 were subsequently driven via Lake Ngami in Botswana during 1893-4 and sold in the markets of the Transvaal and Cape Colony. The proceeds were deposited into a “Loot” Fund which was distributed to the volunteers as pay for their services in the 1893, but also to the BSA Company to finance its own general administrative and war costs.

J.G. Millais writes in his book on the life of Selous that it was whilst travelling to Essexvale that Selous met his old friend, Mr. Helm, the missionary, who by his long residence amongst the Matabele was thoroughly conversant with their views. Mr. Helm said that on the whole they had accepted the new regime, but that they were highly incensed at the confiscation of their cattle by the BSA Company. They had been told that all the cattle would be branded with the BSA Company’s mark and handed back, only the King’s cattle would be confiscated. Selous said; “this promise was made under the belief that nearly all the cattle in Matabeland had belonged to the King and that the private owners had been but few in number.” This was a great mistake as nearly every Induna and any man of position had large herds of their own.” Millais states there were about 70,000 cattle in the hands of the Matabele and the final agreement reached was for the BSA Company to keep two-fifths, or 28,000.

Acknowledgements

F.C. Selous. Sunshine & Storm in Rhodesia. Vol 2 Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1968

F.C. Selous. A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa. Vol 14 Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1970

F.C. Selous. Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa. Vol 25 Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1972

J.G. Millais. Life of Frederick Courtenay Selous, D.S.O., Capt. 25th Royal Fusiliers

M. Selous. National Archives of Zimbabwe SE 1/1/1