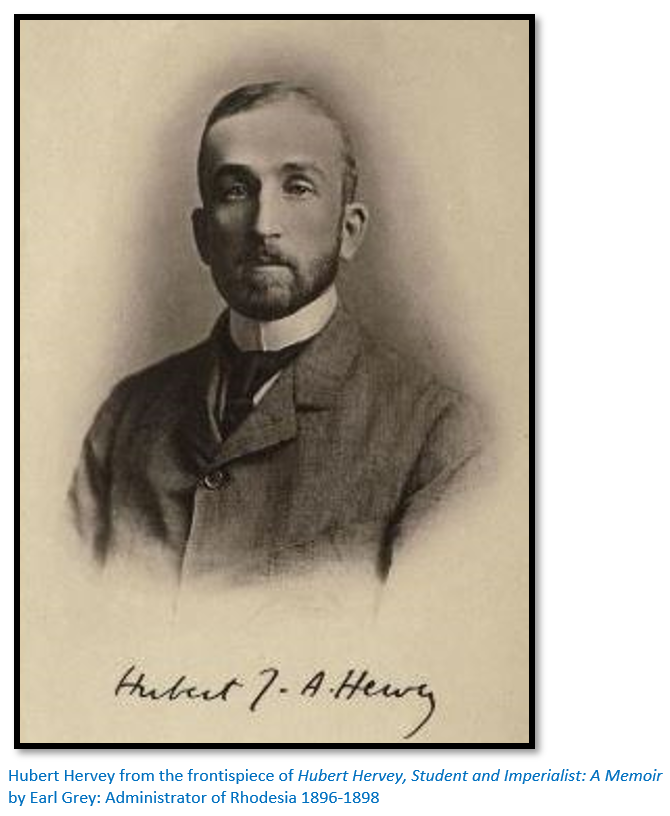

Hubert John Antony Hervey (1859 – 1896)

Hubert Hervey, the youngest son of Lord and Lady Alfred Hervey arrived in Rhodesia well-educated, but was described as having a delicate physique. Time spent in the saddle as a trooper in the 1893 Matabele War and on various missions for Jameson in Gazaland and Mocambique soon led to his transformation into muscular health.

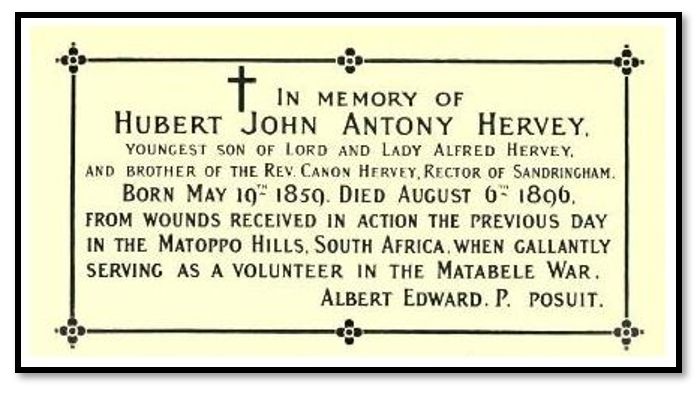

His death at the battle of Tshingengoma at the young age of 37 cut short a life of promise and potential. He had just been appointed by the British South Africa Company as Deputy Administrator in Barotseland; a position he never lived to fill. His great friend Robert Coryndon took over the post; then went on to become Resident Commissioner in Swaziland and Basutoland and finally Governor of Uganda and then Kenya.

Hubert Hervey’s relative Earl Grey succeeded Jameson as Administrator of Rhodesia between the years 1896 – 1898 and claims authorship to Hubert Hervey Student and Imperialist a Memoir. Jono Waters states in Heritage No 35 of 2016 on Page 123 that the book was in fact ghost written by Hugh Marshall Hole.

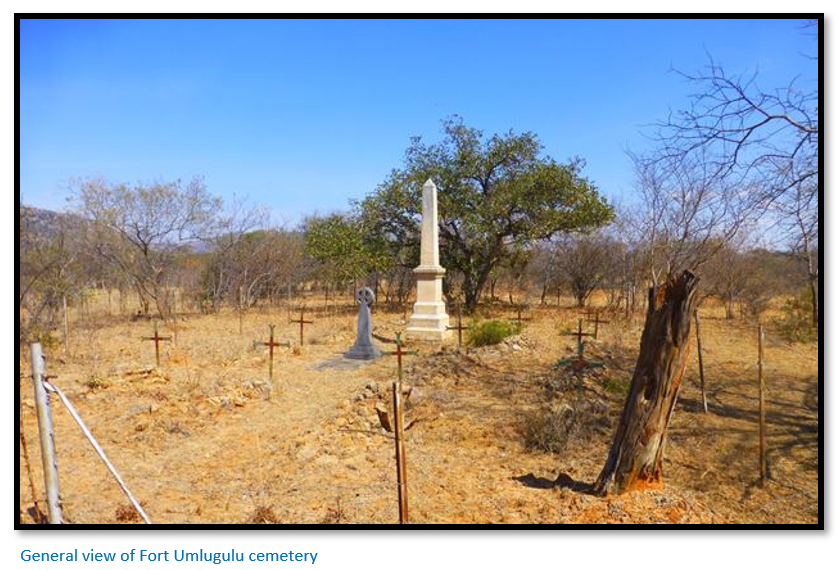

He is buried at Umlugulu Cemetery along with other soldiers and volunteers on the edge of the Matobo Hills, a few kilometres from the battlefield. [See under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com for a description of Fort Umlugulu and the cemetery]

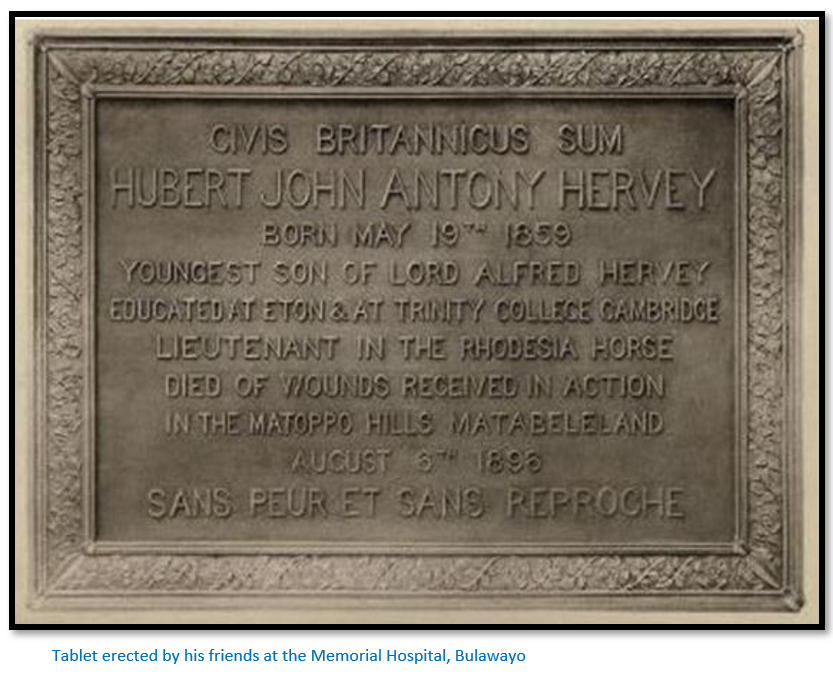

His life is celebrated at Falcon College at Esigodini; the boarding school has six houses for the students, one of which is Hervey House. In addition to his grave memorial at Fort Umlugulu cemetery, there are memorial plaques at Eton, Sandringham Church and the Memorial Hospital, Bulawayo.

His grave is at Fort Umlugulu.

From Bulawayo take the A6 towards Gwanda, but turn right at the turnoff just before Mawabeni ( 57.5 KM peg) Drive the untarred road 10 KM to Esibomvu. At Esibomvu there is a cross roads about 100 metres after Esibomvu Clinic. For Dian’s Pool, turn left down the road signposted “Diana’s Pool 9 KM / Rhodes Indaba site 7 KM”. For Fort Umlugulu continue straight on (i.e. ignore the Diana’s Pool Rd) another 180 metres and turn left at Patsy Store (opposite Hanyana Store on the other side of the road) and continue south towards the Matobo hills. At 400 metres turn right and follow the track west past houses and a modern cemetery on the left. At 950 metres follow the dogleg left and follow the track, at 2.1 KM cross the stream and park on the left immediately afterwards. Up to this point the road is suitable for ordinary vehicles, as long as they have good ground clearance.

In a suitable vehicle, you can drive a further 250m along a poor track in a south easterly direction to the highest point of the ridge facing the Matobo hills towards the large Acacia galpinii which are located near the fort. If you have left your vehicle at the stream crossing, then walk along the same directions. In the wet season the undergrowth makes this difficult to locate.

For the cemetery follow the path that runs along the stream going east and then the edge of the dam to the cemetery which is just south of the earth dam wall. If you are at the Fort, then follow the paths from there in an easterly direction, on top of the ridge and in the direction of the dam wall.

GPS reference for the cemetery: 20⁰24′40.59″S 28⁰53′07.94″E

Eton and Cambridge (1859 – 1881)

Hubert Hervey was born on 19 May 1859 at Eaton Place, London, the youngest son of Lord and Lady Alfred Hervey. His father represented Brighton in Parliament from 1841 to 1857; from 1859 to 1865 he represented Bury St Edmunds. He was appointed Lord of the Bedchamber in the Prince of Wales’ household and then Receiver-General of Inland Revenue under Gladstone. He died in April 1875.

Hubert entered Eton in September 1871 at twelve years old; was remembered affectionately by his masters and then in 1874 was sent to Dresden with a private tutor to learn German in preparation for an army career. However when his father died in 1875, his mother decided he should go to University rather than the army.

He entered Trinity College in October 1877 and despite trouble with his eyes which made reading difficult, passed his Classical Tripos in 1881.

Actually, this book was ghost-written for Earl Grey by Hugh Marshall Hole.

London (1882 – 1890)

He worked in London on a number of exhibitions; the International Health Exhibition of 1884, the Inventions Exhibition of 1885 and finally the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 which awakened his interest in political and imperial subjects.

On 8 Feb 1885 Hubert wrote in a letter: “There is something inspiriting in being one of a great nation…do you ever feel a desire for adventure? I feel an attraction to an adventurous career like Gordon’s [General Charles George; soldier and administrator, killed at Khartoum] and I should delight in explorations like Livingstone’s into mid-Africa.”

Here he developed his central philosophy that a man can have no greater privilege than to devote his energies, his health and his life to the extension of the British Empire.

British South Africa Company (1891 – 1892)

In January 1891 he joined the British South Africa Company (BSAC) probably because he identified with the wide-reaching and imperial goals that the Charter Company had set for itself. For nearly two years he worked in the share transfer department of the BSAC. One of his companions said of this time: “the expansion of the Empire was the idea for which he lived and for which he gave his life.” He would probably have travelled to Africa long before he did, but for his Mother’s failing health which kept him in London, but with her death in September 1892 he made plans to leave for South Africa.

His great friend, later Sir Eyre Crewe KCMG, wrote that Hervey “believed in the boundless capacities of the English race. With her ever-growing healthy population, her superfluity of energetic young men, full of resource and the spirit of enterprise, gifted with the power to rule honestly and justly, ready to go anywhere, and yet dearly attached to their national ideas; he could see no reason why England should not provide governors and administrators for the whole as yet uncivilized world, just as she was doing for India, Egypt and the various African territories.”

En route to Rhodesia 1892

Hervey volunteered to work unpaid in Mashonaland if a post could be found for him. Lord Montague of Beaulieu, a fellow passenger on the Union Line’s SS Scot wrote: “there was something peculiarly noble and high-minded about him, besides his great gentleness and sympathy, he was the most delightful companion and the truest of friends.”

He sailed to Durban and then by coach to Johannesburg, Pretoria to Pietersburg and then by Cape cart and mules to the Limpopo River and on to Fort Tuli and BSAC territory. He left from Tuli to Fort Victoria in a Scotch cart drawn by oxen with a Dutch driver and African voorloper. He wrote: “There are some stores along the road, but one generally sleeps on the veld, with a mackintosh sheet underneath and blankets are discretionary. There is a great deal of fever in the wet season between Tuli and Victoria, as it lies low. Little game is seen on the roads and the journey is tedious and monotonous… Victoria is a small township, a few brick buildings, mud huts and some gold mines in the neighbourhood. Thence onto Salisbury in six days still by ox cart.”

Hervey arrived in Salisbury on 26 March 1893 and was appointed Secretary to the Law department under the Public Prosecutor. Salisbury he described as: “the best and pleasantest place in Mashonaland to live in; we have brick Government buildings; a brick club, and altogether there are many brick buildings, which are rapidly supplanting mud huts. There are chapels and churches of various denominations, stores, golf, a tennis court, a hospital and a very pleasant set of people, though naturally a rowdy and disreputable element as well, but this is the case in all new countries. The town is practically divided into two geographical sections, the ‘Koppi’ where most of the business buildings at present are, and the ‘Causeway’ or Government side, which is a much pleasanter and quiet place to live in, and has the government buildings, club, post and telegraph office, bank and hospital.”

The Matabele War 1893 - 1894

As the inevitably of a fight with the amaNdebele became obvious, Hervey volunteered as a Trooper under Captain Heany and served in the same four man mess and became firm fiends with George Grey; a fellow trooper, who wrote: “physically he was not well suited for the severe ‘roughing it’ and long monotonous duties which he had to go through; he was quite inexperienced in the management of horses and arms, and had practically never before camped out in the veldt. He set himself however to learn everything that was required of him, and soon knew his drill, and was as well up in all the duties of a Trooper as any other of the recruits, and such was his spirit and determination that he never allowed lack of strength and physical weariness to hinder him from doing his full share of the work of the troop.”

He fought with his troop at the battles of Shangani and Bembesi, called Bonko and Egodade by the amaNdebele. [For accounts of these battles see under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

George Grey continues: “The hardest time we had on this campaign came after the occupation of Bulawayo. Food was short and we had to live partly on what could be obtained from the natives, such as corn and mealies. During the latter part of November and December we had to patrol in almost constant rain, and endured no little hardship in consequence. Perhaps the hardest physical test that Hervey went through was on the relief expedition sent to bring in Forbes’ Shangani patrol.

With others he rode out some twenty-five miles from Inyati to the relief of Forbes and his men, and giving up his horse to one of the patrol, himself walked back the twenty-five miles in the rain and mud.”

Major Robert Coryndon, later Sir RT Coryndon KCMG Resident Commissioner in Swaziland and then Basutoland, Governor of Uganda and then Kenya, was a Sergeant in Captain Heany’s troop and knew Hubert Hervey well and wrote: “This troop was made up of ordinary police and volunteer forces in Rhodesia, and I presume in other new countries, of all sorts and conditions of men, and of the forty-five men know, no one would strike an observer as less qualified by nature and training to make a success of the rough work, and of what must have often been, to his exceedingly refined nature, very uncongenial society.

Yet the very first man to offer for a ‘fatigue,’ or to volunteer for a guard, the very last to come with complaints to the non-coms, the nicest mannered, and the most pleasant to work with, was the essentially gentlemanly, Hubert Hervey. Never a word of grumbling during the longest and most exhausting night-rides, never sulky or bad-tempered, always willing to make some dry, witty remark, and always ready to do another man’s turn; he got to be known before the troops were disbanded as one of the best, as he was the most conscientious of the troop.”

Working under Jameson (1894 - 1895)

In Bulawayo, Hervey was personally congratulated by Rhodes for his efforts and given overall charge of a new BSAC Department in Salisbury, that of Records and Statistics, which he led until the outbreak of the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela. He undertook a number of missions for Jameson. One was to Gazaland and included Umtali (now Mutare) and Melsetter (now Chimanimani)

In June 1894 Jameson sent him down to Chimoio in Manica Province of Mozambique to bring up materials for the Africa Trans-Continental telegraph line from the railhead of the Beira-Mashonaland railway.

On 16 June Hervey wrote: “I am off to Beira, and all that country, for about three months…on Company’s business, connected with railway matters. I travel as follows: Here to Umtali, post-cart, three days; Umtali to Chimoio, donkeys and ‘boys’ (native carriers) seventy-five miles; Chimoio to seventy-five mile peg (on railway); thirty-five mile walk (‘fly’ country); seventy-five mile peg to Fontesvilla (on railway) Fontesvilla to Beira, forty miles, by river steamer.”

He was back in Salisbury by mid-September and I October 1894 took over the duties of Civil Commissioner in Salisbury when Marshall Hole, one of his closest friends, went on leave and took on his duties until Marshall Hole returned in July 1895. In addition to being Acting Civil Commissioner, Hervey was still in charge of records and Statistics, as well as acting Registrar of Deeds and later to be Acting Magistrate of Salisbury.

He made a second visit to Gazaland and wrote from Melsetter on 4 December 1894: “the evening is the pleasantest time travelling, it is cool, the fire is cheerful, and one has not got to be thinking of going on again, so one quietly eats one’s supper (much the same as breakfast…bread, tea or coffee, tinned meats and jam) and smokes one’s cigarette or cigar afterwards, reclining on blankets (with a waterproof sheet underneath one) and looking up at the wonderful stars. Then to sleep about nine. You will see it is a thoroughly healthy, frugal, and altogether pastoral, or Arcadian, or what-so-ever-the right word is life!”

He first met Jesser Coope; one of his greatest friends, in early 1894 with Coope was laid up in Salisbury hospital with a severe bout of malaria. He came every day to talk and when Coope was too ill to talk; Hervey would read aloud for hours, mainly Shelley.

Coope wrote: “He always had a great longing to explore the country, and absolutely loved the free gipsy-like life we led on the veldt; and was never so happy as when, after a hard day’s work, we lay beside our campfire, our horses and native attendants forming a picturesque background.”

Hugh Marshall Hole, who wrote the Mashonaland Rebellion section of the British South Africa Company’s Reports on the Native Disturbances in Rhodesia 1896-7, later reprinted as The ’96 Rebellions by Books of Rhodesia and numerous other books, wrote of Hervey: “No one who had once gained his friendship ever willingly forfeited it, and those who were his friend will cherish his memory with an affection that will always remain.”

Lady Henry Paulet wrote: “my recollections are chiefly of those peaceful days at Salisbury. I knew him best as the kindest and most hospitable of neighbours…we had many and long conversations on the subject always nearest his heart and uppermost in his mind – the Empire and its expansion. To this his whole life and energies were devoted, and for this no journey was too long, no hardship or privation too severe.”

Lady Paulet reveals that his nickname was “John” Hervey as he was very much like his ancestor, the memoir writer, John, Lord Hervey.

He was worried by his brother Algernon’s health and arrived in England in November 1895 after three year’s absence. All his family were amazed that the open air life of the veldt had transformed him…his former look of delicacy had been replaced by one of wiry health and activity.

Shortly after arriving in England he was told by the BSAC that he had been selected to be their first Deputy Administrator of Barotseland. This region between Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Angola is the homeland of the Malozi people, or Barotse. He was ordered to proceed there once his leave was finished and make the best arrangement with King Lewanika to ensure that the area fell under British control.

He spent Christmas 1895 with his brother Algernon and his sister Mary; but the disastrous Jameson raid over the New Year weekend of 1895-6 cut short his holiday and he arrived back in Cape Town in January making his way by coach to Bulawayo and arriving on 8 March 1896.

The Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela (1896 – 1897)

Early in 1896 he rode from Bulawayo to meet Cecil Rhodes who had travelled inland from Beira. He had just arrived in Salisbury (now Harare) when the Matabele Rebellion (First Umvukela) broke out. Hervey was Intelligence Officer for the Rhodesia Horse and volunteered for active service being commissioned into Col. Beal’s force and joining the Scouts under Capt. Arthur Eyre.

On 10 April Col. Beal’s force and Rhodes left Salisbury and Hervey wrote to his sister from Gwelo (now Gweru) where they put down resistance at Maven, a hotbed of resistance to the northwest, although Hervey complained light-heartedly that he had not yet heard a shot fired in anger.

Col Beal’s column met up with Col. Napier’s column from Bulawayo near the Shangani River and the combined column moved south as far as Filabusi before turning back and reaching Bulawayo by 1 June. In a letter to his sister he notes it was still unsafe to travel in small parties, the mail route to Salisbury was still closed, although the main centres of Salisbury, Bulawayo, Fort Victoria and Gwelo were safe, the countryside was still dangerous. “The great difficulty is that they won’t stay to fight in any large force, so that the whole thing is being gradually reduced to tedious guerrilla warfare.”

Earl Grey had arrived shortly before and appointed Hervey as Paymaster of the active forces; a position he only reluctantly accepted as he preferred active service to remaining in Bulawayo and only accepted when Earl Grey explained he wanted the best man for the job. Writing to his sister on 16 June: “you need not be anxious now that I am paymaster; I am not campaigning, and Bulawayo itself is as safe as Piccadilly.”

Bulawayo 19 June: “We now hear of the murder of white people by natives in Mashonaland…this means that Mashonaland too is unsafe in the outlying districts for prospectors, miners and farmers. The country is indeed having a trying time of it. The towns are always, however, perfectly safe. I am very well.”

Bulawayo 6 July: “It is just possible we may get news today or tomorrow that Col. Plumer’s force that have gone north to Thamas Imambi [Ntaba zika Mambo] may have a fight, but I doubt it, I think the Matabele will clear. The next move will probably be against the Matoppo Hills [Matobo]”

12 July; “I am confident that sooner or later the whole of South Africa will be federated under British protection.”

15 July: “In this present business I have not seen a shot fired, but after all, why is a bullet going within a yard or two more dangerous that a hansom cab nearly running one over as it passes a corner?”

Earl Grey then released Hervey from his duties as Paymaster, appointing Major Everett in his position, and released him on active duties.

23 July: “I am going tomorrow to the Matoppos, where General Carrington and Colonel Plumer are in command. I have lots of friends there…I am so pleased to get to active service again…all this was only settled today.”

Colonel Plumer gave Hervey a commission as a Lieutenant and command of a detachment of about fifty men; some from the Bulawayo Field Force, but most from Major Robertson’s Cape Volunteers.

29 July: “We are moving on next Friday, but you need not be anxious about me. Of course, we may have a little fighting, but that will be over long before you get this letter, so that if I were at all hurt, you would hear about this by cable long before you get this. [This letter and six others, reached his sister after the news of his death] Lovely weather. This is quite a picnic.”

On 1 August Col. Plumer’s column marched from Usher’s Farm and had a small engagement with the amaNdebele at the head of the Umchabaze Valley before moving up the Tuli road to Dawson’s Store where they camped. The next day the column rested and it was from here that Hervey wrote the last letter to his sister.

3 August: “We shelled some kopjes yesterday, but there was very little firing otherwise, and only one man slightly wounded on our side. I have not much news for you…the Matoppos are a difficult country; rocky kopjes, with caves in them, in which the Matabele can hide. We generally get up about 5:30; breakfast about 8; (early cocoa at 6) lunch 12; dinner 7; bed 8:30, or 9. It is very pretty country all about the hills, and day after day comes with certainty of a cloudless sky and a brilliant sun.”

On 4 August the column marched to the Fort Umlugulu site, then called Sugar-bush Camp, on a ridge overlooking the Nsezi River. [There is an article on Fort Umlugulu on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Next day a force of 760 left before daybreak to attack Chief’s Umlugulu and Sikombo’s strongholds on the east of the Matobo Hills. At 6:15 the force was in a space between two bald kopjes opening into a valley in front of Tshingengoma Hill. [A detailed article is being prepared on this battle on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Colonel Plumer ordered all the dismounted men, including Hervey’s detachment forward under Capt. Beresford with the seven-pounder guns to take up a position on a hill to the west of Sikombo’s main position, subsequently called “case-shot kopje,” which when captured would enable the guns to shell most of the surrounding area.

About an hour into their climb up the right-hand side of the valley, Beresford’s force was surprised by a large number of amaNdebele who had crept up on them unobserved and surrounded them and began to fire at short range from the cover of caves and boulders. The seven-pounders had been positioned without an advance guard and this nearly ended in disaster as they were rushed by the amaNdebele and the Artillery Troop only just managed to limber up the guns and fire case shot at point-blank range to halt their progress.

Battery Sgt-Major Ainslie was killed here. To the left of the seven-pounders on the hill slope Captain Hoël Llewelyn operated the Maxim gun single-handed and stopped a further charge; Tpr Holmes seeing Llewellyn unsupported ran to his assistance and was mortally wounded in the thigh and died four days later.

To the right of the seven-pounders Lieutenant Hervey was ordered to attack and as he stood on a rock waving his men forward was shot and mortally wounded. He was laid on a stretcher in the shelter of two large boulders, telling his men to continue on fighting. The engagement became more general, Capt. Jesser Coope with his scouts was unable to reach Beresford who had managed to signal that he was being heavily pressed, with Hervey severely wounded.

It took an hour for reinforcements to push back the amaNdebele and then Coope spent a few minutes with Hervey who was calm and collected and did not appear to be in pain. He commented to Weston Jarvis that although he was shot in the abdomen, he only felt an aching in his legs.

All the regiments of Chief’s Umlugulu and Sikombo were now engaged and the rocky ground favoured the amaNdebele who inflicted further heavy casualties. Major Kershaw led an attack at 11am to the left of the Tshingengoma Hill and was shot dead, Major Robertson’s Cape Volunteers attacked at 12am; Baden-Powell led an attack half an hour later and the AmaNdebele slowly began to retreat.

AmaNdebele losses were estimated at around 200; Plumer’s forces lost five killed and fifteen wounded, of which two subsequently died of wounds. Those buried within the cemetery include:

Name | Unit | Place | Status | Date of Death |

Worringham, Frederick C. Sgt | MMP | Babayana's kraal | KIA | 20th July 1896 |

Bennett, Peter Tpr. | MMP | Inugu (T-Laing) | KIA | 20th July 1896 |

Bush, William H. Tpr. | MMP | Inugu (T-Laing) | KIA | 20th July 1896 |

Hall, John Cpl. | BeFF | Inugu (T-Laing) | KIA | 20th July 1896 |

Morgan, Charles O. Tpr. | BFF | Inugu (T-Laing) | wounds | 23rd July 1896 |

Bern, William Tpr. | BFF | Inugu (Nicholson) | wounds | 27th July 1896 |

Cheves, Laurence Tpr. | BFF | Inugu (Nicholson) | wounds | 27th July 1896 |

Little, Edward R. Tpr. | MRF | Spargo store | accident | 3rd August 1896 |

Ainslie, Alexander Battery Sgt-Maj. | MMP | Sikombo | KIA | 5th August 1896 |

Gibb, William, Sgt. | MRF | Sikombo | KIA | 5th August 1896 |

Innes-Ker Archibald Sgt. | MRF | Sikombo | KIA | 5th August 1896 |

Kershaw, Frederick E. Maj. | MRF | Sikombo | KIA | 5th August 1896 |

McCloskie, Oswald D. Sgt-Maj. | MRF | Sikombo | KIA | 5th August 1896 |

Hervey, Hubert J.A. Lt. | MRF | Sikombo | wounds | 6th August 1896 |

Holmes, Alfred J.E. Tpr. | MRF | Sikombo | wounds | 9th August 1896 |

Parr, Harry A. Tpr. | MRF | Inseza camp | typhoid | 17th August 1896 |

MMP = Matabeland Mounted Police | ||||

BFF = Bulawayo Field Force | ||||

BeFF = Belingwe Field Force | ||||

MRF = Matabeland Relief Force |

Those killed at the battle of Tshingengoma (Sikombo’s stronghold) with Lieutenant Hubert Hervey are highlighted in grey.

After the fight was over, Colonel Plumer spoke to Hervey and wrote: ‘He asked me all about the details of the fight and when I told him we had inflicted a pretty severe defeat on the rebels, he said: “oh, that is alright, I don’t mind a bit now.” He knew quite well he was dying and the way he faced death is a lesson to us all.

When Jesser Coope again talked to Hervey at 6pm, he looked so well that it was hard to believe he was dying. His men carried him back to camp to save him the pain from the jarring of the wagon on uneven ground. To one he said: “who knows but that I may soon be pegging out claims for England in Jupiter!” and when they reached Fort Umlugulu in the dark he said; “Well, it is a grand thing to die for the expansion of the Empire.”

His great friend Captain Jesser Coope stayed all night with him in the hospital tent as he dictated messages to his family. On the morning of 6 August he was visited by Rhodes, Major-General Carrington and Colonel Plumer and Rhodes promised that his pension would be paid to his sister.

He passed away so quietly that Coope who sat by his side noticed nothing and had to be told by Dr Lunan that it was all over.

He was carried to his grave just before sundown on the same evening of 6 August 1896 by Captains Beresford, Garden, Whitaker, Coope and the two Llewellyn’s. Captain Scott Turner was in charge of volley firing and salutes, Colonel Plumer read the service, Carrington and Rhodes and all officers and men attended the burial.

His memorial plaque at Ford Umlugulu states:

To the Memory |

Honoured and much loved of |

Hubert John Antony Hervey |

Youngest son of Lord and Lady Alfred Hervey |

And grandson of Frederick William |

First Marquess of Bristol |

Born May 19 - 1859 |

Died August 6 - 1896 |

Having been mortally wounded in action |

August 5, in the Matoppo Hills |

When gallantly serving as a volunteer |

In the Matabele War |

His deeply sorrowing brothers, |

Sister, and sister-in-law erected |

This Cross |

Fort Umlugulu cemetery where Hervey and his comrades lie is on the western side of the old Bulawayo – Tuli road and near to Fort Umlugulu in a beautiful spot in the shadow of the Matobo Hills and a few kilometres from the first Indaba site. [There is an article on the First Indaba site on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Military casualties of the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela

What is very noticeable is the high number of officers and NCO’s that were casualties of the battle of Tshingengoma, or Sikombo’s stronghold. The amaNdebele had certainly learned from their experiences and adapted their military strategy following their decisive defeats at the battles of Shangani (Bonko) and Bembezi (Egodade) in 1893. No longer would they make mass charges on strongly defended positions protected by Maxim guns and seven pounders, but would themselves defend the rocky fastness of the Matobo and Ntaba zika Mambo hills.

In the western Matobo, a column under Captain Tyrie-Laing had laagered in a poorly-sited defensive position overlooked by kopjes on two sides and had been very nearly overrun at what is known as “Laing’s graveyard.” The amaNdebele had been able to get under cover within 30 metres of the laager; Captain Tyrie-Laing showed much courage in rallying his men; but was criticised for choosing a laager site best described ‘as a nasty place’ and those that escaped considered it a miracle.

At Tshingengoma Hill, or Sikombo the dismounted detachment, to which Lieutenant Harvey belonged and the artillery, all under the command of Captain Beresford, were surrounded on three sides by the amaNdebele and the seven pounders which had been pushed forward without an advance guard were forced to fire case-shot at extremely close range to avoid being overrun. Case, or canister shot is only used at distances of under 350 metres; the case was loaded with lead or iron balls and the container disintegrated on leaving the gun muzzle and the balls fanned out as the equivalent of a shotgun blast.

The heroic action of Captain Hoël Llewelyn who single-handedly swept his front with a Maxim gun forced the amaNdebele into retiring under cover and changing from an offensive into a defensive strategy, but it had been very touch and go. The amaNdebele had employed their tactics of firing from cover and then charging at short range extremely effectively.

In counterattacking the amaNdebele, Officers and NCO’s took the initiative and led the charge. Both Major Kershaw and Lieutenant Hervey and their NCO’s are described as leading their men on and were shot down in situations very similar to those experienced in the early days of WWI when officers and NCO’s suffered heavy casualties in infantry charges against opposition under cover and making effective use of their rifles. Many native police had deserted to the amaNdebele cause in 1896 with their rifles and were well trained in their use.

Most of the material in this article comes from the book on Hubert Hervey by Albert Henry George Grey, the fourth Earl Grey, appointed by the BSAC to be Administrator of Rhodesia from 1896 – 1898 during the Matabele Rebellion, or First Umvukela. The book was dedicated to ‘the Civil Servants of Rhodesia.’ However, Jono Waters states in Heritage magazine No 35 of 2016 on Page 123, that the book was in fact ghost-written by Hugh Marshall Hole.

Earl Grey was also responsible for the section on the Matabele Rebellion in the British South Africa Company’s Reports on the Native Disturbances in Rhodesia 1896-7, later reprinted as The ’96 Rebellions by Books of Rhodesia. The ’96 Reports sought to explain this expensive setback soon after the abortive Jameson Raid to the Charter Company’s shareholders and was hurriedly put together and a completely one-sided account.

Acknowledgements

G. Grey. Hubert Hervey, Student and Imperialist; A Memoir. Edward Arnold, London 1899.

J. Waters in Heritage No 35 for 2016 Page 123 that the above book was ghost written by Hugh Marshall Hole.

The ’96 Rebellions. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1972.

F.W. Sykes. With Plumer in Matabeleland. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1972