Fort Usher No. 3

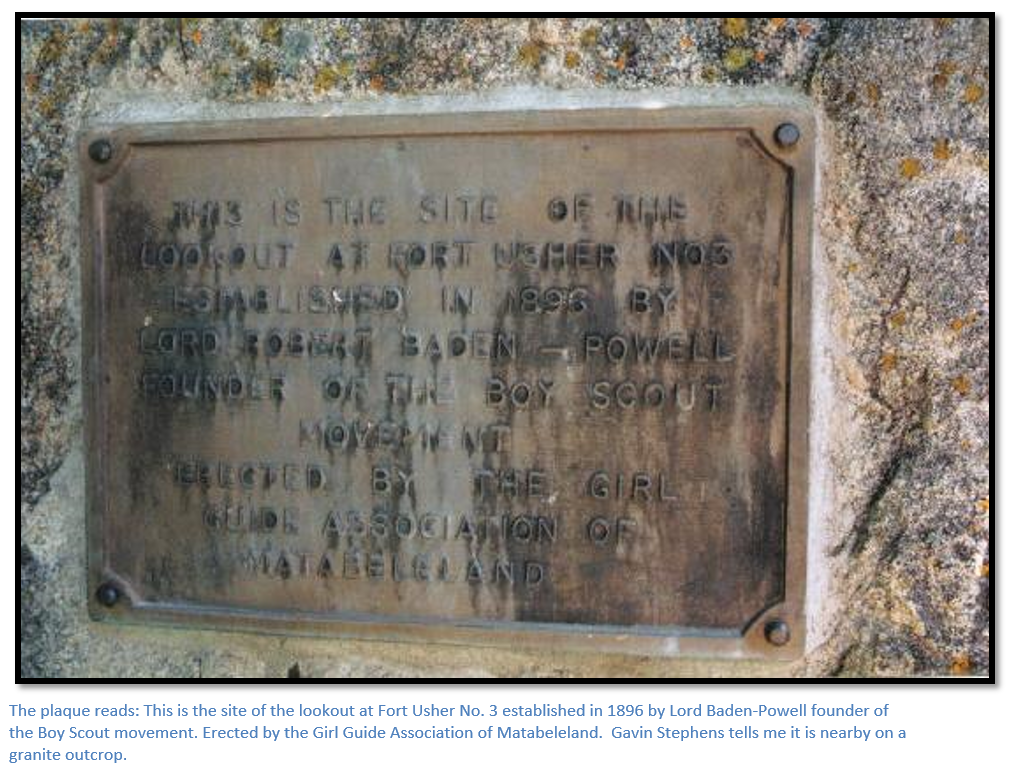

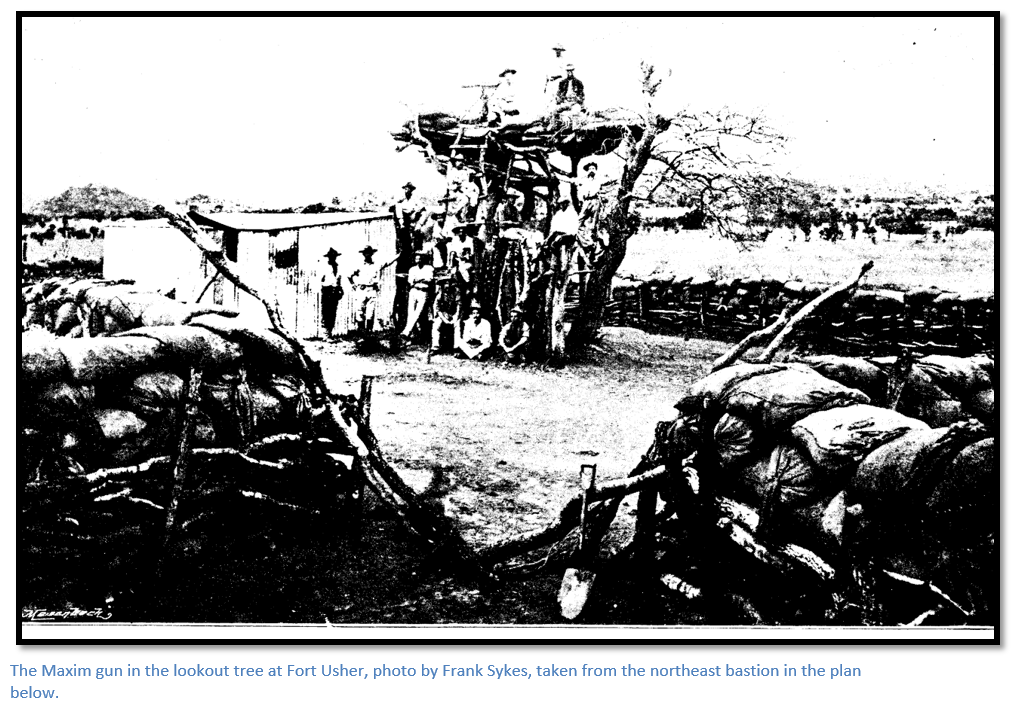

- This historic fort with its lookout tree and platform for a Maxim gun was designed by Robert Baden-Powell, later founder of the Boy Scouts movement.

- The fort was built on the 23rd July after the action against the Induna Babayan’s stronghold which was attacked at Kantolo Hill. The battle was not a success; but the fort was used to bottle up the Kantolo valley against the amaNdebele forces.

- Named after William Filmer Usher, an early trader and farmer, it was used as a base by Rhodes during the Matabele uprising / First Umvukela and it was from here that he rode to the second and third Indabas which were held at the base of Lahlamkonto hill; “the place where the spears were laid down” and about 1.6 kilometres from Fort Usher.

- The third official Indaba was held on the 9th September 1896, with Queen Victoria’s representative, Sir Richard Martin and Earl Grey, the Administrator also present, along with Rhodes, Colenbrander, Rev. D. Carnegie, Father Barthelemy, Chief Native Commissioner Taylor, Col. Plumer, Major Robertson, Lady Grey and her daughter and Mollie Colenbrander. Sir Richard Martin had twelve mounted lancers as an escort who carried the Union Jack. The Chiefs included Sikombo, Dhliso, Nconcobela, Sikota, Ntweni, Nhluni, Mabesa, Nyanda, Babayane, Nhlukoniso and Kaal Khumalo.

- The patient’s rooms of the former Fort Usher hospital survive as six brick rooms in a courtyard west of the existing farmhouse which is 950 metres from the Fort Usher No 3 site.

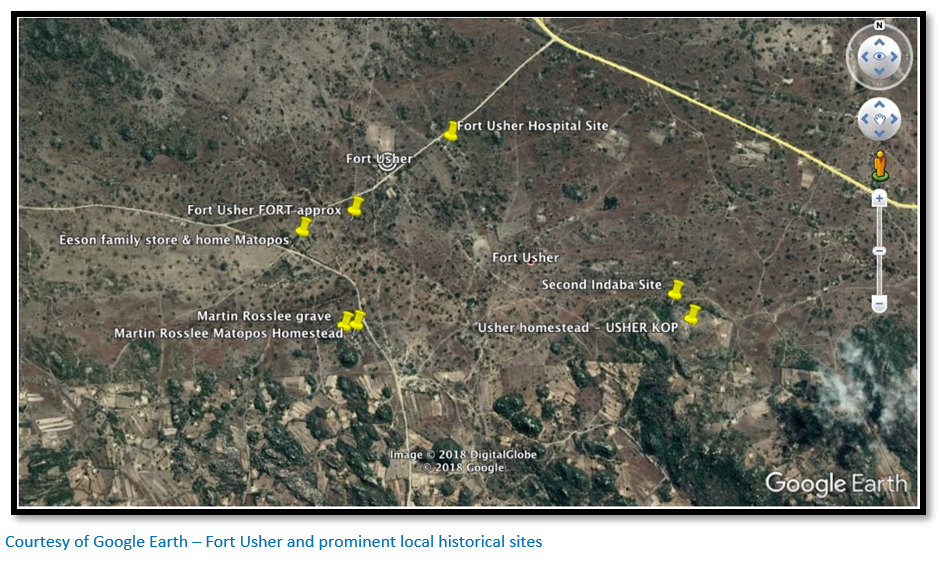

From Bulawayo take the Matobo road and then take the Old Gwanda Road. Distances are from the Matobo / Old Gwanda road intersection. At 14.5 KM pass the Mzilikazi Memorial on your right, at 21 KM pass some granite outcrops. At 21.8 KM pass the national monuments sign on the right indicating the Mzilikazi gravesite, 25.1 KM turn right off the Old Gwanda Road, 26.2 KM turn left for the hospital site and park.

The hospital site is on the east side of the road 400 metres north east of the School at the site of a farmhouse marked by tall gum trees.

The fort site is described by I.J. Cross as 90 metres south of the road, 183 metres east of the bridge crossing the Kantolo River. The bridge crossing the Kantolo River is 950 metres south of the turnoff to the hospital site. In 1972 when I.J. Cross wrote his article on Rebellion Forts on Matabeleland, the tree; originally the lookout and Maxim gun platform, still survived.

From Bulawayo using the Matobo road pass the Research Station and turn left for the Matobo National Park. Distances are from the intersection. 1.4 KM turn left on the untarred road signposted Fort Usher, 9KM take the left fork at the intersection, 9.7 KM reach the bridge over the Kantolo River, 9.9 KM park for the Fort Usher site 90 metres south of the road.

GPS reference for Fort Usher No.3 site: 20⁰24′48.67″S 28⁰35′15.77″E

GPS reference for Fort Usher hospital: 20⁰24′33.65″S 28⁰35′39.22″E

William Filmer (his mother’s maiden name) Usher was born on 16 September 1851 and baptised at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel at Bathurst in the Eastern Cape which had been originally established by the 1820 settlors. He came with his brother Reuben Usher to Matabeleland as pre-pioneers and they initially traded and lived amongst the amaNdebele who gave William the name of Mapondo; a reference to the area from which he originally came. After marrying Mzondwase Khumalo, he was given an extensive tract of land called Tshabalala by Lobengula in 1883.

Usher lived in traditional amaNdebele style with his large family farming on the banks of the Phekwe stream; evidence of their occupation can be found in the terraces made on the stream bank where Usher made a vegetable garden and the remains of a stone wall that formed part of his cattle pens. Usher himself died on the 22 September 1916 and was buried next to the walls that had formed his cattle pens; his grave site is within the boundary of what is now the Tshabalala Game Sanctuary. His brother Reuben is buried at Gwanda.

In 1897 Usher's farm was purchased from him and incorporated into the Rhodes Estate and became part of the Sauerdale Block, Dr Hans Sauer having negotiated the purchase of a number of farms on behalf of Rhodes. After the death of Rhodes in 1902, Jock Brebner was asked by the administrators of the Estate to develop the Tshabalala Section and took on the lease of the property in 1905. After the lease expired in July 1978 Tshabalala was designated as a Game Park and is currently managed by the Zimbabwe Department of National Parks and Wildlife.

I am grateful to Rob Burrett, Associate Researcher at the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe for sending me the Google Earth image below – his wife is a descendant of the Usher family.

Lobengula’s original kraal at koBulawayo had its own “white man’s camp” but Lobengula soon moved to Umhlabathini near today’s Government House and allocated an area of land on the other side of the Amajoda stream where Europeans might live. In 1893 they included James Fairbairn and the Dawson brothers, all living in brick houses, and in 1888 John Smith Moffat (the son of Robert Moffat) who lived in a tent and then a pole and dhaka thatched hut. In 1890 Capt. Ferguson visited Bulawayo and writes of others “surrounded by ring fences of thorny mimosa bush” including the British South Africa Company (BSAC) compound, and that of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company where E.A. Maund lived, and another lived in by Edward Renny-Tailyour. Johan and Mollie Colenbrander lived 6 kilometres away to the north, although a year later they moved next to the BSAC compound.

In June 1893, a Chief in the Victoria district refused to pay tribute, asserting that he was now under settler protection and the laws of the settlers. To save face, Lobengula sent a raiding party of several thousand warriors which destroyed several villages and murdered many of the inhabitants. The BSAC administration had to intervene to avoid losing the confidence of the local people and demanded that the raiders leave immediately. John Meikle wrote in his diary: “meanwhile the Matabele were not idle. Night after night the sky was lit up east of the town and huts were burning where the impis passed through with assegais and fire. For fifty miles the country was laid waste and not a kraal was left standing. The inmates, however, for the most part took refuge with their flocks and herds in inaccessible places. Their greatest loss was their granaries which meant they would have to go short of food until the next season’s crop was harvested.”

Benjamin “Matabele” Wilson was in Bulawayo and wrote; “when we were leaving the King’s kraal that night we met Mlegela, the King’s brother. We stood outside the kraal sometime talking with him. He told us that the King was sending Umgandeni with an impi to Victoria to punish the natives and that they would not bring back any slaves. They would do as Mzilikazi, the King’s father, had done; sweep them off the face of the earth, which meant the wholesale massacre of the Mashonas.”

As the war clouds began to gather in Bulawayo; many left. The Inyathi (formerly Inyati) missionaries went south; Benjamin “Matabele” Wilson went to Mashonaland; Lobengula’s interpreter William Tainton, panicked and left the king’s kraal without permission. Harry Grant was allowed to leave with some of the King’s cattle; P.D. Crewe left on an official mission for Lobengula to see the British government in Cape Town and to complain about the BSA Company’s behaviour. Johan Colenbrander went to Palapye to buy guns for the amaNdebele regiments, and Dawson left with three indunas to make contact with the force marching on Bulawayo from Fort Tuli. This comprised 220 men of the Bechuanaland Border Police under Colonel Hamilton Goold-Adams, Commandant Raaff with 235 volunteers and 700 Bechuanas under Khama III.

However, James Fairbairn and William Usher were refused permission to leave Bulawayo by Lobengula but were provided with an amaNdebele bodyguard. By the 3 November 1893 the Salisbury / Fort Victoria column was only a few miles from the royal kraal and acting on the King’s orders, Induna Sivalo set fire to the kraal. 900 kgs. of gunpowder exploded and 80,000 rounds of Martini-Henry ammunition started to go off. Fairbairn and Usher could hear the sound of shots coming from the direction of Thabas Induna as they spent the night of 3/4 November 1893, on the roof of Dawson’s store with their rifles, plenty of ammunition and a pack of cards. Matabele Wilson says: “next morning we saw from where we were the explosion which blew up the King’s house and all his belongings. A great column of smoke went up towards the sky and the higher it got the more it seemed to spread out til it took the shape of an enormous umbrella.” The scouts Frank Burnham, Harry Posselt and Pearl Ingram found Fairbairn and Usher playing poker on the roof of Dawson’s store.

After 1893 William Usher, through his long-time local contacts maintained loudly and consistently to the BSA Company officials that an amaNdebele uprising was inevitable; the response of the administration was that he would be clapped in gaol if he continued to spread alarm and despondency.

During the Matabeleland Rebellion or First Umvukela of 1896, many soldiers and some civilians fell in the area and were noted as buried at Usher’s farm.

On Thursday 27 August 1896 the second Indaba took place six days after the first Indaba at the foot of the kopje on which William Usher had his farmhouse, now called by the local inhabitants Lahlamkonto, “the place where the spears were laid down” and about 1.6 kilometres from Fort Usher. Accompanying Rhodes were Johan and Mollie Colenbrander and her sister Mrs Smith, Chief Native Commissioner Taylor, J. Grimmer, J. G. McDonald, FitzStubbs and the Mangwe Native Commissioner, Bonar Armstrong. Colonel Plumer with Lieut Moncrieff and Tpr Laurie, Vere Stent of the Cape Times and Mr Witt of the Bulawayo Chronicle were also present. Most of the Indunas were present along with 350 young men, all armed, but Colenbrander refused to start the Indaba until all weapons were left at a safe distance. Once again, Rhodes had tied up his horse as a symbol of trust and seated himself on a boulder within a few metres of the amaNdebele indunas and their followers.

The main issue of the Indaba was if it was to be peace or war. The young men seemed eager to continue the fight and complained bitterly about Chiefs Faku, Gambo and others who had sided with the Europeans. Rhodes refused to listen to these complaints and when they continued loudly with their complaints Induna Dhliso reprimanded them. All this time, the Maxim gun up on the lookout tree at Fort Usher was loaded and trained in their direction and the garrison with horses saddled was ready to ride to the Indaba site at a moment’s notice.

The third official Indaba was held on the 9th September 1896, also at Fort Usher, at which the Queen Victoria’s representative, Sir Richard Martin and Earl Grey, the Administrator were present; also, Rhodes, Colenbrander, Rev. D. Carnegie, Father Barthelemy, Chief Native Commissioner Taylor, Col. Plumer, Major Robertson, Lady Grey and her daughter and Mollie Colenbrander. Sir Richard Martin had twelve mounted lancers as an escort who carried the Union Jack. The Chiefs included Sikombo, Dhliso, Nconcobela, Sikota, Ntweni, Nhluni, Mabesa, Nyanda, Babayane, Nhlukoniso and Kaal Khumalo.

Colenbrander told the Chiefs that Earl Grey had come to take Jameson’s place and that Queen Victoria had sent Sir Richard Martin as her representative. Earl Grey told them that they should come out of the Matobo Hills to rebuild their houses and cultivate their gardens and that they should give up their weapons and that only those responsible for carrying out murders and tried in Court would be punished. Sir Richard Martin said much the same and was followed by Rhodes who said they should all make peace. The Chiefs said they were afraid but were reassured by Rhodes who said he would stay and listen to their grievances.

In 1897 Usher's farm was purchased from Usher by Hans Sauer, Rhodes’ right-hand man in Bulawayo and incorporated into the Rhodes Estate and became part of Sauerdale Block.

Jock Brebner had arrived in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) in 1902 to work on the Rhodes Estate Research station and in 1905, after the death of Rhodes, the Estate Administrators asked him to develop the Tshabalala Section on a lifelong lease, this being Rhodes’ wish that the farms be developed for the instruction of the people of Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe)

The lease given expired in July 1978 and Tshabalala was designated as a Game Park under the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Authority.

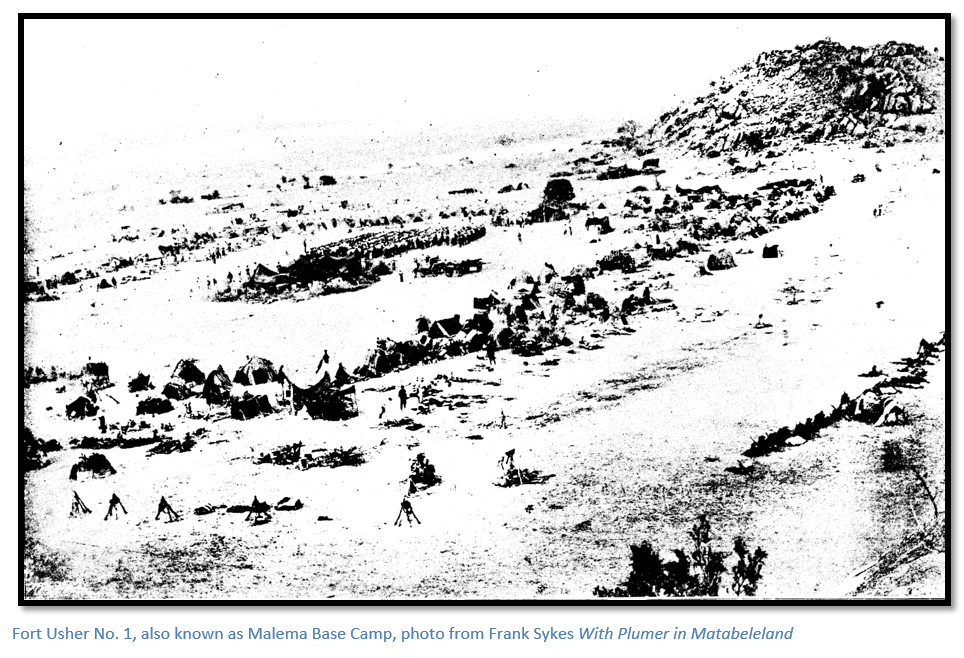

Fort Usher No. 1, also known as Malema Base Camp, was established on 13th July 1896 by Col. H Plumer, who was commanding the Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF) with 1,300 men and is about eleven kilometres north of the actual Matobo hills, close to the headwaters of the Maleme River. He was joined by Lt-Col. Robert Baden-Powell of the 13th Hussars who was his Chief Staff Officer.

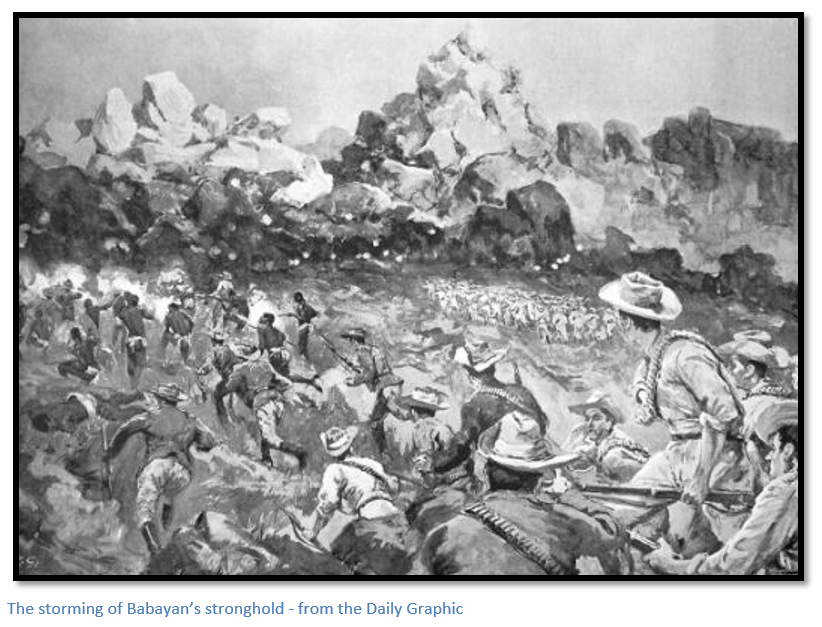

Fort Usher No. 2 was established on 19 July. From here on the 20 July 1896 Induna Babayane was attacked at Kantolo Hill, about sixteen kilometres away. The force left at 9:30 pm on Sunday evening under the personal command of Major-General Sir Frederick Carrington as it was planned to carry out a dawn attack. They were led by the Scouts with “friendlies” on either flank, the Matabeleland Mounted Police (MMP) now dismounted, A and B Squadrons of the Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF) the Cape Volunteers, and Colenbrander’s Native Contingent, Maxim and Hotchkiss units of the MMP, Mountain Battery of the Royal Artillery, Maxim unit of the MRF, Lieut. Mathias’ Troop and E Squadron of the MRF

After marching for two hours, the force attempted to sleep on the ground in overcoats for four hours. The hospital wagon and heavy equipment were left here and the final march of five kilometres started. At dawn the Kantolo valley and Babayan’s stronghold could be seen. The Mountain battery opened fire, the amaNdebele were seen running for the cover of the rocks and Colenbrander’s native contingent and “friendlies” moved forward with the Scouts. The amaNdebele were driven out of a kraal in the valley which was then set on fire and then heavy shooting began in the vicinity of Babayan’s stronghold.

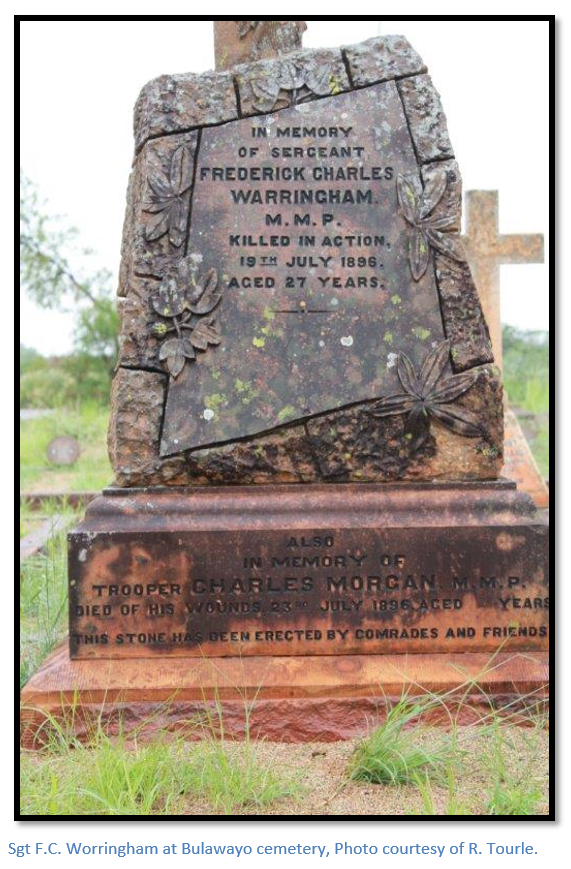

The amaNdebele after a short sharp resistance broke under the attack of Capt. Robertson’s 160 strong Cape Volunteers supported by a Hotchkiss and two Maxim guns and fled over the kopjes to the south. The European forces, with the exception of the Scouts, were simply spectators. Sgt F.C. Worringham, attached to the Scouts, was mortally wounded and buried near the main road; his headstone is in the Bulawayo cemetery.

Frank Sykes says how the amaNdebele made good tactical use of the mountainous nature of the terrain; the easy successes at Shangani (Bonko) and Bembesi (Egodade) [see these articles under Matabeleland South Province] when they had charged the Maxim guns “isi-kwa-kwa” and were then exposed to their crushing fire at short range were not about to be repeated and the warriors no longer believed that the higher they set their sights, the harder the bullet would impact. However, the attack on Babayan’s stronghold in the Kantolo valley cannot be considered a military success for Carrington’s force.

Three days later Fort Usher No 3 was designed and sited by Baden-Powell to command this area of the Matobo. Baden-Powell also suggested the fort should be sited with a tall tree in the centre to act as a crow’s nest and lookout and a platform for an elevated field of fire for a Maxim gun. He recommended a wide belt of grass in the immediate vicinity of the fort which would show up the dark bodies of any attackers at night with a burnt out outer ring of grass to provide a fireguard and prevent attackers to use the cover of smoke in an attack.

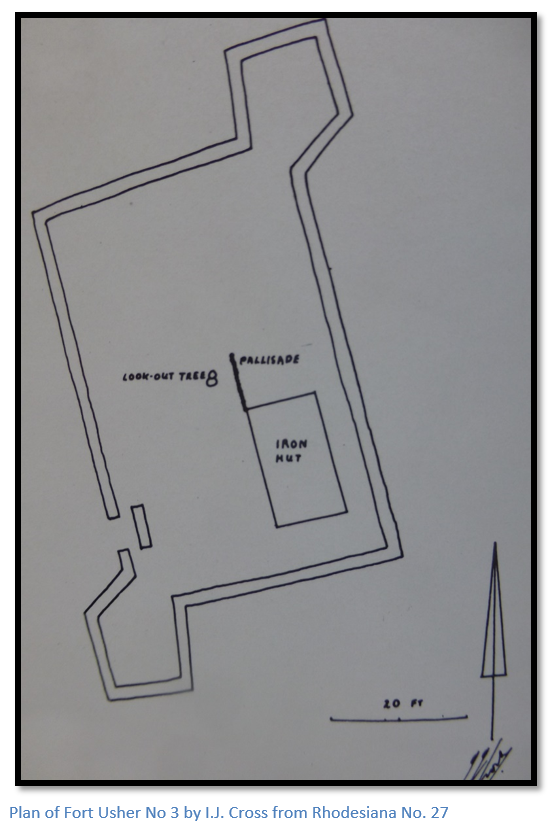

The fort consisted of a low wall of horizontally placed timbers which were reinforced and protected by sandbags. Two rectangular bastions or gun emplacements also projected from diagonally opposite north and south corners; these were different from the earlier square or round shaped enclosures of 1890 and there was no surrounding ditch. [For a similar design of fort see Fort Que Que under Midlands Province]

I.J. Cross wrote in 1972 that the fort was demolished when the old district administration offices were built here and only the lookout tree then survived, but even that has now gone.

Fort Usher hospital

Parts of the hospital remain; a series of six hospital rooms face each other in two rows of three across a swept courtyard, near the present farmhouse. The brickwork is of very high standard and the buildings have stood the test of time remarkably well; the corrugated iron roofs still being weatherproof. Approximately four patients’ beds could have been accommodated in each room and presumably they were separated to cope with contagious diseases. They were built on stone and cement foundation platforms 30 cms above the courtyard to keep them dry and clean.

Acknowledgements

N. Jones. Rhodesian Genesis. Rhodesia Pioneers and Early Settlers’ Society. 1952

O.N. Ransford. White Man's Camp: Bulawayo. Rhodesiana Magazine No. 3, P.13

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia, 1890-1897. Rhodesiana Magazine No. 12, Sept 1965, Pages 37-62

I.J. Cross. Rebellion Forts in Matabeleland. Rhodesiana Magazine No. 27, Dec 1972, Pages 1-28

F. Sykes. With Plumer in Matabeleland. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1972

Rod Tourle and Gavin Stephens for advice and information