Filabusi Memorial and the Edkins Store killings

- This historic site remembers one of the earliest European murders of the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela of 1896. There seems no doubt that the initial killings occurred on Monday 23 and Tuesday 24 March 1896. Arthur Bentley, the Assistant Native Commissioner was found at his desk with Monday 23 March on his half-written letter.

- His killing and those at Edkins Store must have occurred in a coordinated way as there is no evidence that the other victims heard Bentley being killed or were in anyway prepared for the attack on them.

- Historically there has been some doubt about the actual date individual victims were killed, but Albert Baragwanath only left Bulawayo on Sunday evening the 22 March “after dinner to ride his rather decrepit horse back in the cool of the night to his store” and was one of the victims, which adds some accuracy to the date of the killings.

- On the evening of Monday 23 March at the Nellie Reef Mine at Insiza Thomas Maddocks was sitting at sunset and smoking with Hocking and Hosking when they were attacked by a group of fifteen amaNdebele with knobkerries and axes; Maddocks was killed, but the other two managed to escape to Harry Cumming’s store five kilometres away. At that time no one knew that eight members of the Cunningham family were already dead.

- Harry Cumming’s reached Bulawayo from Insiza on Tuesday 24 March in the morning; Arthur Cumming and Lucas from Filabusi reached Bulawayo on Wednesday 25 March at 2am with the news. The fact that both have the surname of Cummings has caused much confusion!

- Joseph O’Connor was the only survivor of the killings and his account was initially taken as fact; subsequent research and oral evidence taken from the amaNdebele who carried out the attacks has proved that some of his story was false. He told Selous that the killings occurred on Tuesday 24th March.

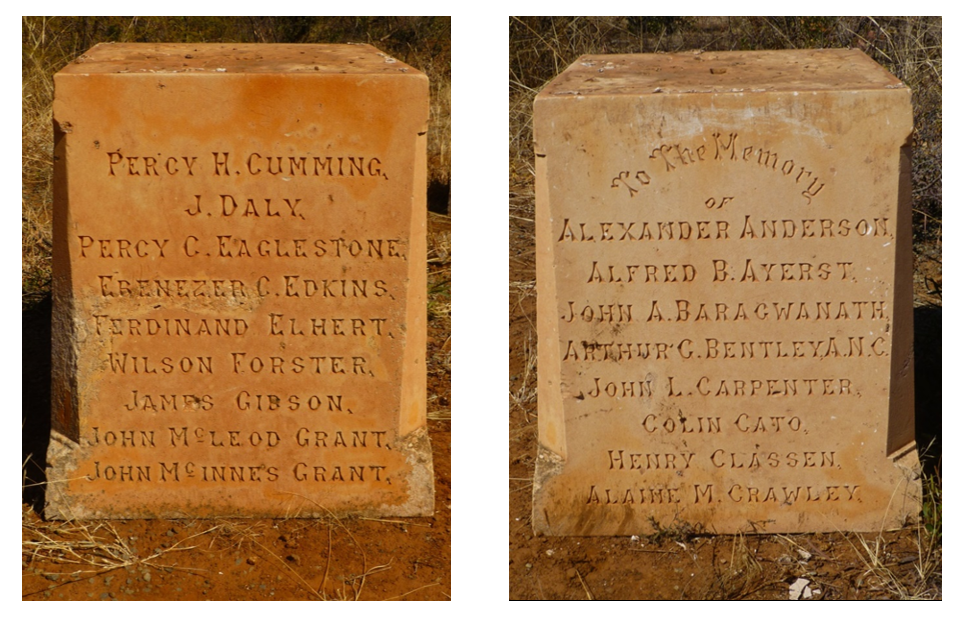

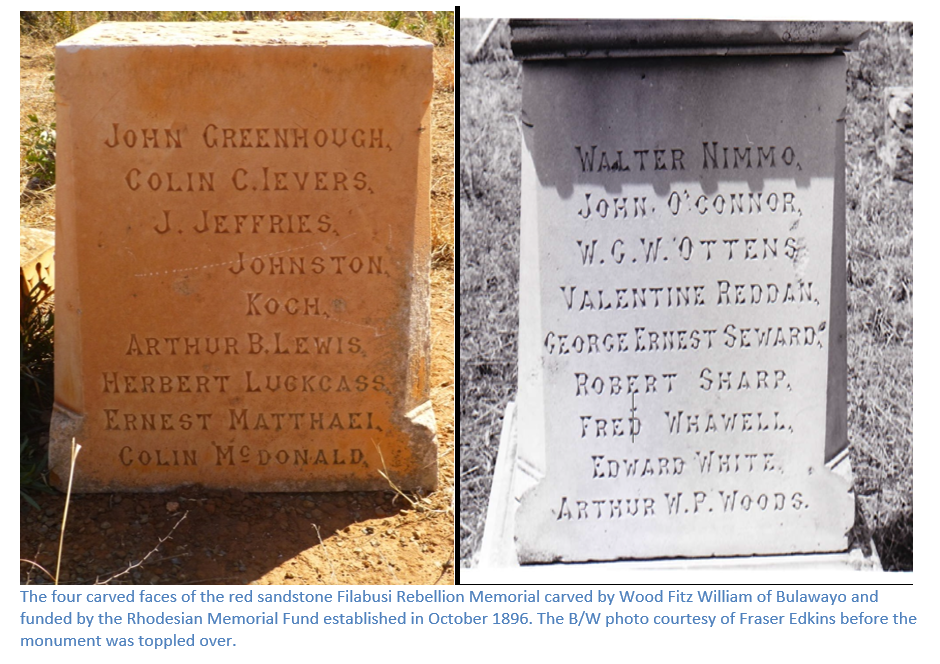

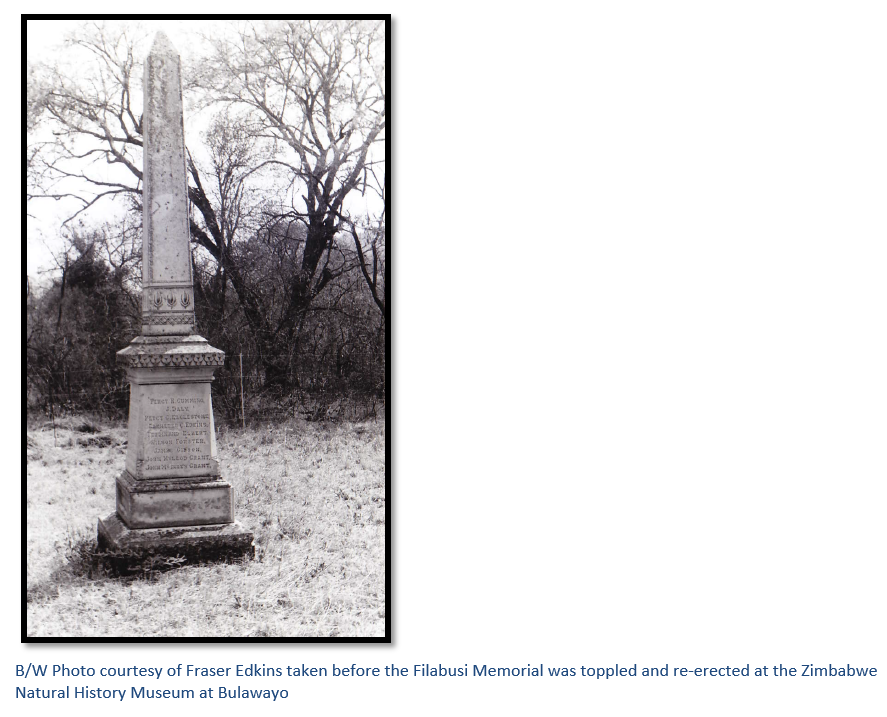

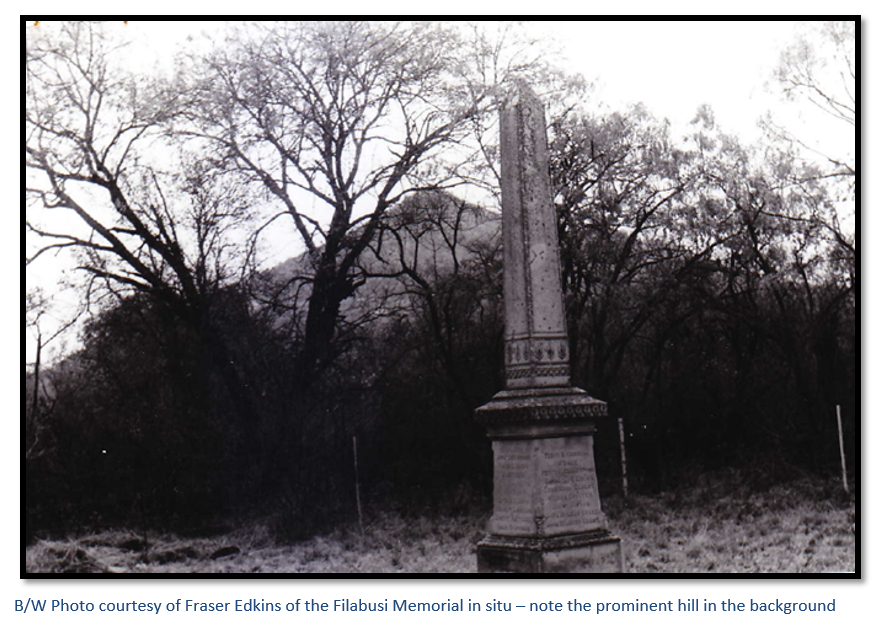

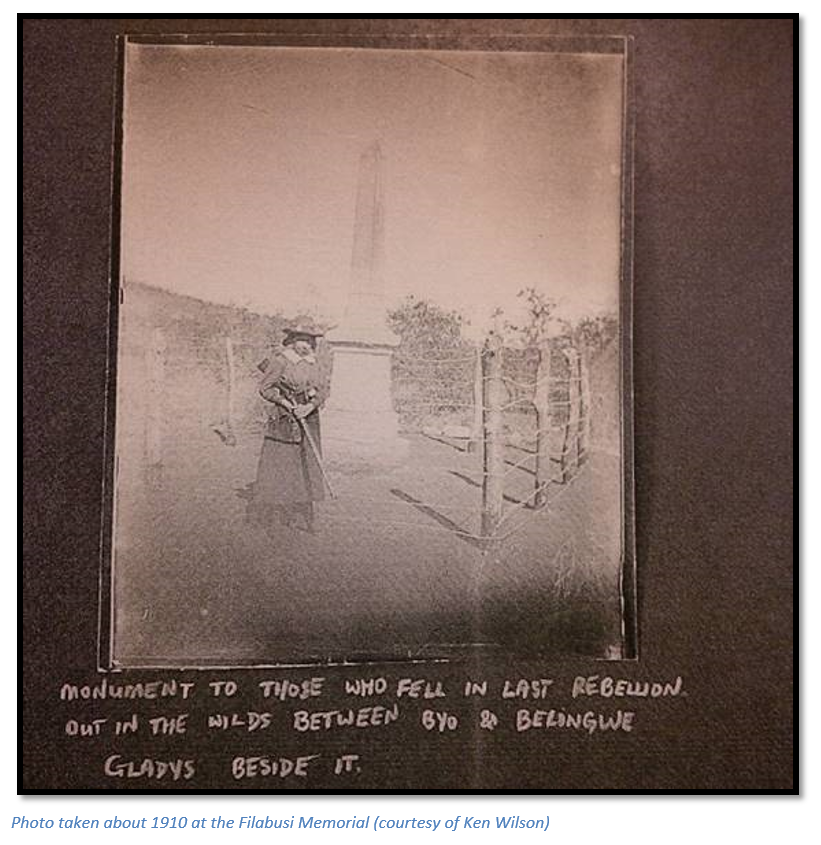

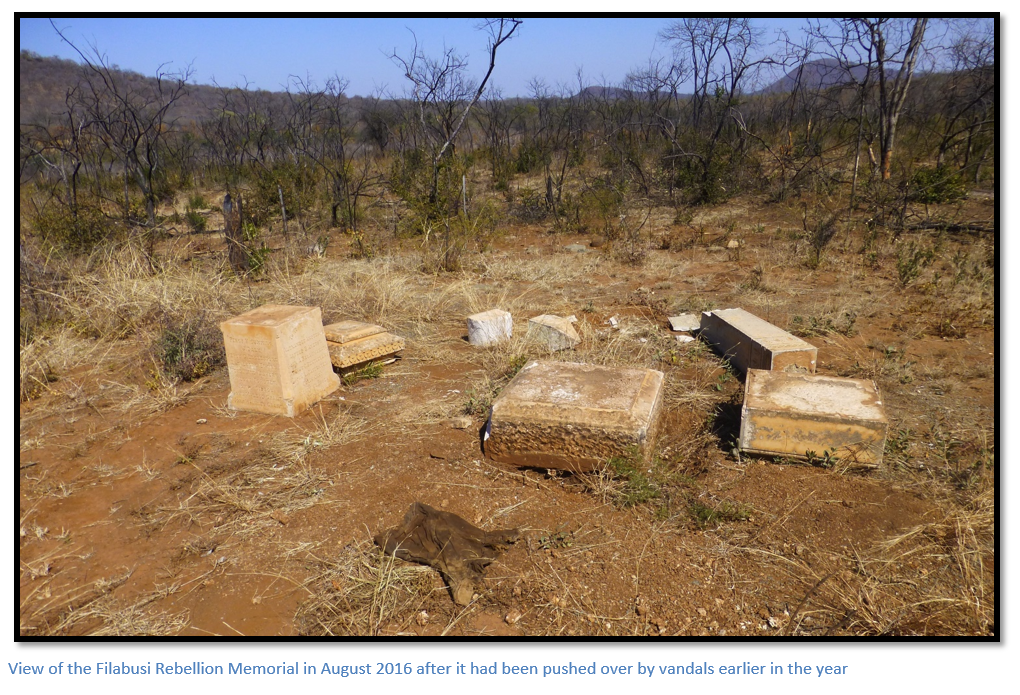

- The Filabusi Rebellion Memorial which was erected to commemorate those killed in late March 1896 was pushed over by vandals in 2016. Fortunately the Museum of Natural History of Zimbabwe – Bulawayo rescued the remains of the Memorial and has re-erected it within the grounds of the Museum in Bulawayo.

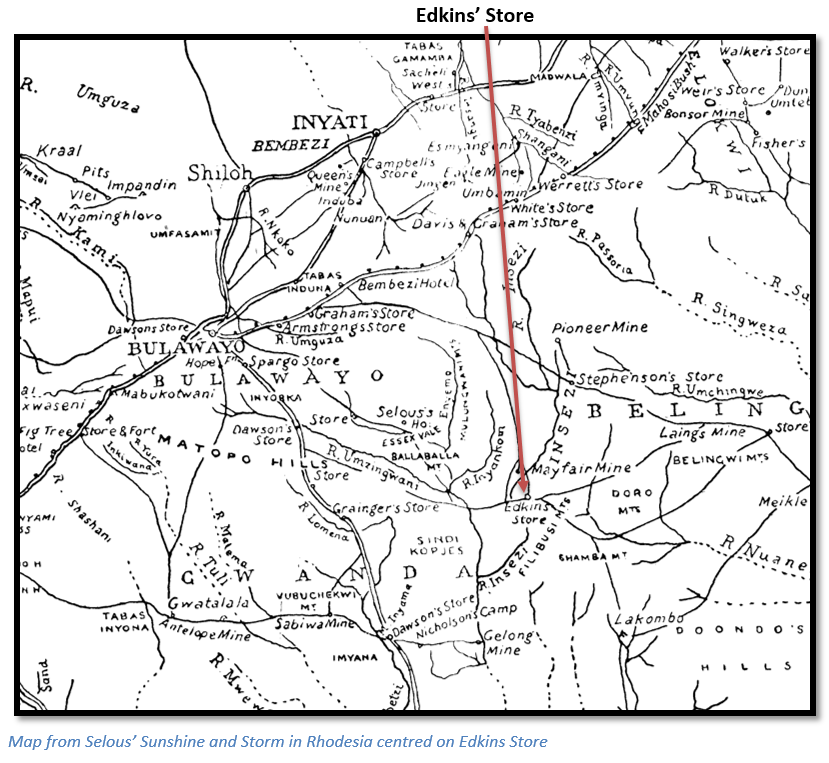

From Bulawayo take the A6 national road down to Mbalabala (formerly Balla Balla) Distances are from the A9 turnoff to Filabusi from Mbalabala. 28.5 KM turn left for the homestead of Annedale Farm on which the Filabusi Memorial, Edkins store and Filabusi old cemetery are located. You should ask permission from Mr Phineas “Fynn” Ngwenyama for his approval to visit the sites. The Annedale Farm homestead is on the right of the A6 national road and clearly visible.

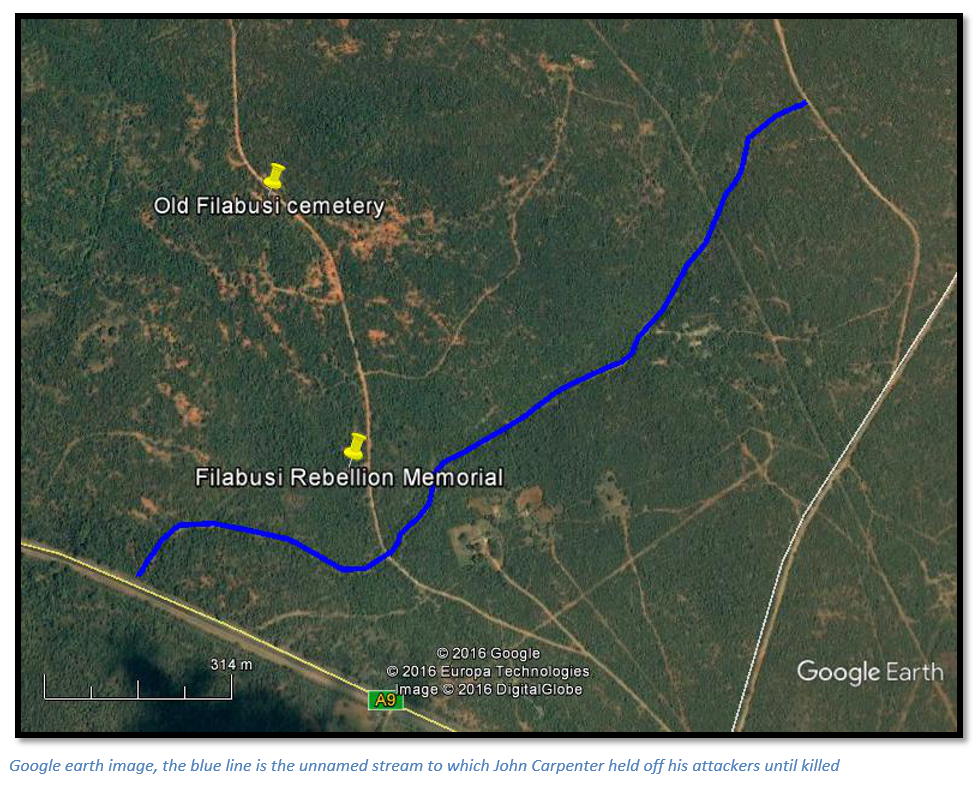

From the farmhouse turn right and drive 0.55 KM down the A9 national road, before turning left onto an untarred road. Drive 100 metres and turn left, you are now on the old Bulawayo - Filabusi – Belingwe coach road. At 300 metres keep left, the right track goes to the McLaren farmhouse only. After 400 metres cross the small stream where John Carpenter was killed, another 150 metres takes you to the site of the Filabusi Rebellion Memorial on the left. The Memorial itself has been moved to the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe at Bulawayo for safe-keeping.

The old cemetery is 450 metres further along from the Filabusi memorial on the south side of the old coach road

GPS reference for Filabusi Memorial: 20⁰29′57.61″S 29⁰17′39.47″E

GPS reference for the cemetery: 20⁰29′41.50″S 29⁰17′34.03″E

Much of the detail has been covered by Fraser Edkins of the killing of Ebenezer Crouch Edkins at Edkins store along with 27 others in the in the immediate area of the Filabusi district on 23 March 1896 and I would recommend this article: Ebenezer Crouch Edkins (1869-1896) The Edkins’ Store killings and Joe O’Connor’s wonderful escape in Heritage of Zimbabwe No 17, 1998. Also, highly recommended is Roger Howman’s article Orlando Baragwanath: A Centenarian Pioneer of Rhodesia in Rhodesiana No 28 dated July 1973.

Then Arthur Cumming reached Bulawayo at 2am on Wednesday 25th March and suddenly everyone realised how much more serious the situation was. Frank Sykes relates how Arthur reached his camp about 20 kilometres from Edkins Store about 11am on the previous day (i.e. Tuesday 24th) to find the mutilated body of his Cape servant in charge of his wagon and oxen lying outside his hut and the store looted. The voorlooper, an amaNdebele youngster told him that Fezela and others had committed the murder and looting. He went to Weir’s Store, about three kilometres away, to warn to warn them of the danger and from here he wrote notes to be sent by runner to his brother Percy Cumming at Filabusi Store, and another to Assistant Native Commissioner Bentley, briefly reporting the murder and looting.

Arthur had then mounted his bicycle to ride to Filabusi to investigate, when he saw a young Mashona servant boy running towards him. The boy gave Cumming an account of how they had all been surprised and killed; Arthur Bentley, the assistant Native Commissioner, was sitting writing in his hut, near Edkins Store, when he was killed. Ebenezer Edkins, Albert Baragwanath, Percy Cumming were also killed together with their two colonial servants and the Indian cook. Only John Carpenter managed to put up a valiant fight in the nearby stream bed before he was also killed. At the Celtic mine just 2.5 kilometres away, Ivers and Ottens died also. As the boy described the events there was a sound of a loud explosion from Filabusi and then they were joined by Edkins cook and Percy Cumming’s herd boy all with the same news.

Arthur Cumming took the boy up onto his horse and turned back for Weir’s Store. His three rifles had been stolen when his Cape servant was killed, and store looted; so unarmed, he and Lucas set off on foot for Bulawayo walking through the night, but keeping clear of the road, to warn the townsfolk and arriving early in the early morning of Wednesday 25th March.

The news caused great alarm. Almost every able-bodied policeman in the country had accompanied Jameson on his abortive raid into the Transvaal and their complete defeat at Doornkop on 2 January 1896 left the amaNdebele jubilant that their former victors were now defeated; to further complicate the situation by February rinderpest had killed most of the oxen, abandoned wagons were left everywhere and transport was at a complete standstill.

A public meeting was called at the Bulawayo Market Square on the same day, Wednesday 25 March; many volunteers quickly signed up, but Bulawayo had only 78 horses and as Jameson had raided the armoury many of the remaining rifles were old or lacked suitable ammunition. Orlando Baragwanath, the murdered Albert’s brother, says they were a “sorry crock” of horses and by Essexvale he and others were six kilometres behind the main party because they had to walk their horses.

Jack Spreckley led a patrol with 35 mounted volunteers down to Filabusi to see if any lives could be saved. They left at 2pm on Wednesday 25th March and arrived at Weir’s store, Orlando Baragwanath says: “what a joy to find a supply of Worcester sauce as a pick-me-up…the store had not been touched.” They reached Edkins Store, in the middle of the gold field at Filabusi at 11am on Thursday 26th March. Here four Europeans (Albert Baragwanath, John Carpenter, Percy Cumming and Ebenezer Edkins) two colonial servants and an Indian Cook had been surprised in the morning and killed with assegais and rifles. Edkins store had been dynamited and blown to pieces and the place was a bloodbath; goods and bodies scattered around, and Orlando Baragwanath broke down when he recognized the remains of his brother, Albert.

Orlando told Roger Howman that providentially at least twenty men had left the Filabusi district on Monday 16 March for Bulawayo as they would not be held up at river crossings, such as the nearby Insiza River. The rainy season was nearly done, and it was time to get stores, to register gold claims, get their shafts dug and to get resupplies from Bulawayo,

Arthur Cumming had a new “safety bicycle” and Albert Baragwanath asked if he could borrow it and made a £25 bet with a man named Peacock, who was travelling on foot, as to who would reach Bulawayo first. Albert won and with his winnings bought a horse and left for Filabusi on Sunday evening and reached Edkins Store next day; so, he had returned before the others, probably on the evening of Monday 23 March, and became one of the victims.

There was no time for Spreckley’s patrol to dig graves and they rode the “few hundred yards” to the Native Commissioners office and Police Camp, where they found Arthur Bentley, who had apparently been taken by surprise and shot through the head and was still in his office chair, with the letter he was writing dated Monday 23 March. Everything was destroyed, even the chickens had been killed and the scene was the same at the Celtic Mine, where several members of the patrol were sick at the sight of the mutilated bodies of Colin Ivers and Wilhelm Ottens.

Joe O’Connor, at the Celtic Mine, whose brother John had not escaped the massacre, was the only European survivor in the Filabusi district. Frank Sykes relates that Chief Maduna Nkojene said that Ivers was killed outright; Ottens was shot in the back and O’Connor they attacked with sticks. O’Connor jumped down the incline shaft and his pursuers threw down dynamite and left him for dead. Maduna Nkojene was astonished to hear that Joe O’Connor was still alive in Bulawayo.

Maduna Nkojene says that they heard firing at Edkins Store. Edkins and Carpenter had been preparing a wagon that Tuesday morning 24 March to take a sick Percy Cumming, brother of Arthur, into Bulawayo. Albert Baragwanath was packing up some of Percy’s belongings, and as he came out of a hut, was shot dead. The store was then rushed and Edkins and Percy Cumming killed. John Carpenter snatched up a rifle and ammunition and kept his assailants at bay from within the store, but on seeing their reinforcements, he set fire to the thatched verandah and shot three of them through the front window. When the fire in the roof grew too hot, he ran to the nearby stream and with his back to a tree kept them at bay with accurate shooting. His assailants called on Assistant Native Commissioner Bentley’s native police to assist, and with a long-range volley, Carpenter was killed in the stream bed.

One of the colonial servants, left for dead with terrible injuries, and found by the Spreckley patrol, did survive. After his wounds were dressed and intensive nursing in Bulawayo, he said the murders were sudden and without warning and led by the native police with local Zansi amaNdebele from the kraal of Lobengula’s brother, Fezela, and Mahladhleni, commander of the Godhlwayo regiment.

The letter below was written by Orlando Baragwanath to his brother-in-law on 30th April 1896.

“On March 16th Albert came to Bulawayo, Cumming and I followed two days later, as I wanted to see about getting a contract. On Saturday [should be Sunday] evening, Albert started back and did not reach Filabusi until Monday night about 9 o' clock.

Arthur Cumming went back on Monday morning on his bicycle and reached our camp (which was about 12 miles west of Filabusi on Tuesday 11 o'clock. As he rode towards the hut he thought everything was very quiet. On looking in there lay our camp boy, who must have been killed Monday morning, or Sunday night, and the place looted. He rode back to the Umzingwane Store - 3 miles distant to send a message to Bentley, the Commissioner, and give notice of the murder, not for a moment thinking a rebellion had started, although there were rumours of it. In fact, old Mr Cumming spoke to Albert about these rumours as he had years of frontier experience.

Arthur decided that he would go himself [to Filabusi] and was preparing to mount his bicycle, when a young native rushed up and told them that everyone at Filabusi had been killed, and the Store was burning. What confirmed this tale was while talking to the boy they heard a big explosion, which turned out afterwards to have exploded at a camp a mile from the Store, but they took it to be the dynamite held in stock at the Store.

Arthur and a man called Lucas started straight away for Bulawayo, and it was early on Wednesday morning that he got into Town. We went to the Administrator and demanded arms, and as they were under British control, owing to the Jameson raid, it was not until 2 O'clock that we got away.

When we got to the Umzingwane Store, we found it in flames. We pushed on as fast as our sorry nags could travel, most of us on foot by then. We reached Filabusi Store, Thursday 11 o'clock.

The Store and Albert's hut were burnt, the other hut intact. Albert's body was the first we came across. It was in front of his hut site. He was shot through the head. His partner Edkins and another, some say Carpenter were the next. In the kitchen a Cape boy. Bentley and others at the Native Affairs post. I was too upset to go to the other camp at the Celtic, Ottens and Ivers. The latter mutilated. We off saddled for a couple of hours as the horses were done up to go to all the camps. The Cunningham family, three generations, about 15 miles off were all killed. Percy Cumming was ill at the Store and just about to leave for Bulawayo in his wagon."

Filabusi Fort

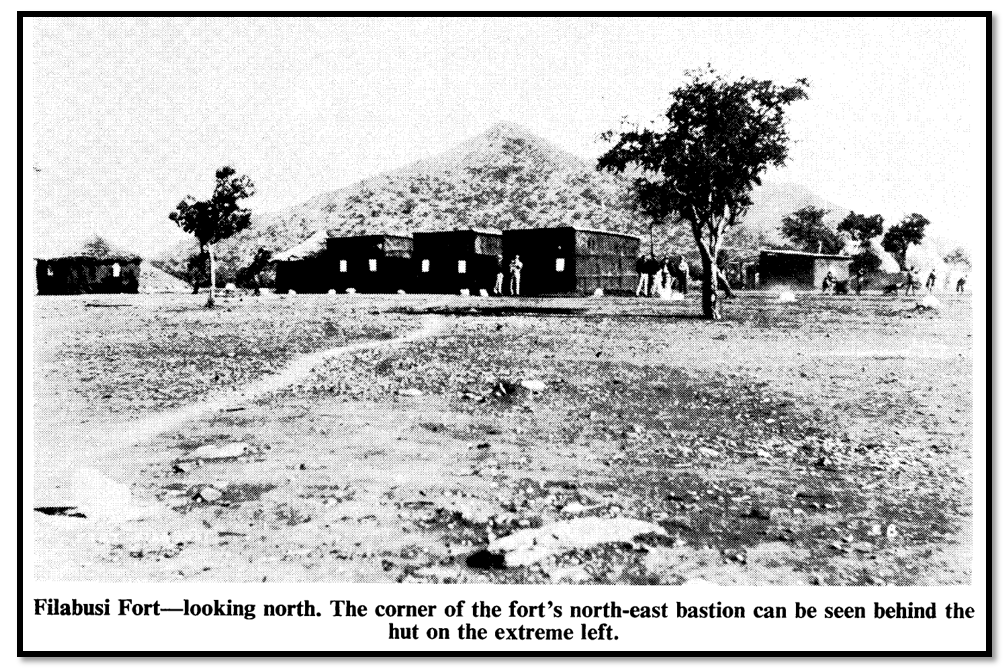

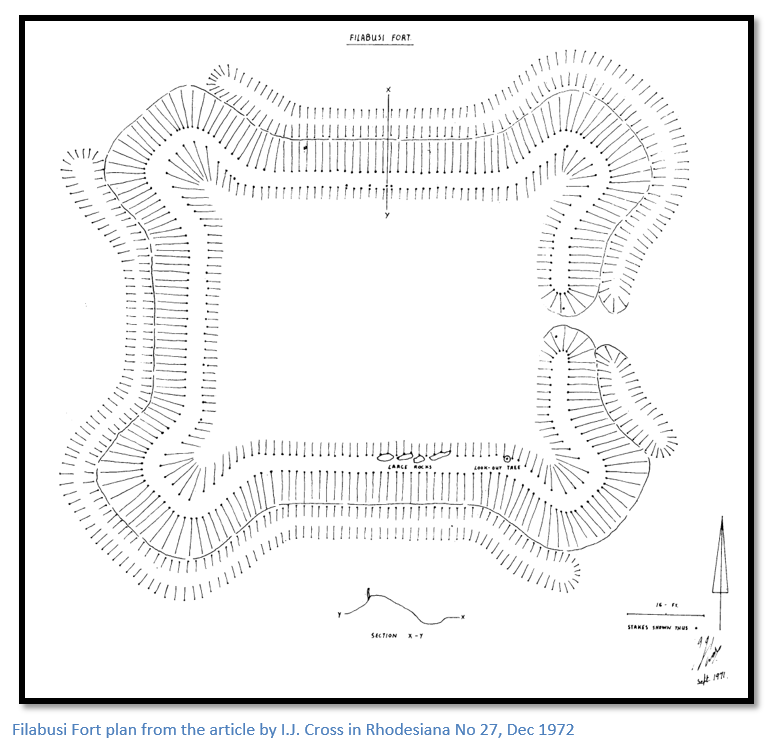

Peter Garlake writes that the small forts at Mpateni near Belingwe (Mberengwa) at Edkins Store, Filabusi; and at Balla Balla (Mbalabala) were all built in the final stages of the Matabele Rebellion, or First Umvukela to pacify the countryside.

The article by I.J. Cross, Rebellion Forts in Matabeleland in Rhodesiana No 27. Dec 1972, contains a treasure trove of information on the 1896 forts constructed in Matabeleland. In 1972 he reported that the earth ramparts at Filabusi fort were still in fair condition and even some of the original timbering was still in place. Only the bases of the huts on the far right of the photo were still visible then; Cross was told by Orlando Baragwanath that these huts belonged to his brother Albert Baragwanath in early 1896 and that he was killed outside them. Orlando, as part of Spreckley’s patrol, identified his dead brother on 26 March 1896. A large tree growing through the ramparts with its branches cut off around 4 metres from the ground to support a crow’s nest was still alive in 1972.

The outline of the ditch was still visible outside the walls and at the entrance to the east wall a wooden bridge originally crossed the ditch.

Orlando Baragwanath also identified the site of Edkins Store and ANC Arthur Bentley’s hut close to the fort and the old Bulawayo – Filabusi – Belingwe road ran just to the north of Filabusi Fort.

Old Filabusi Cemetery

The cemetery is 400 metres north of the Filabusi Memorial and, like the Memorial, on the west side of the stream which runs from north east to south west.

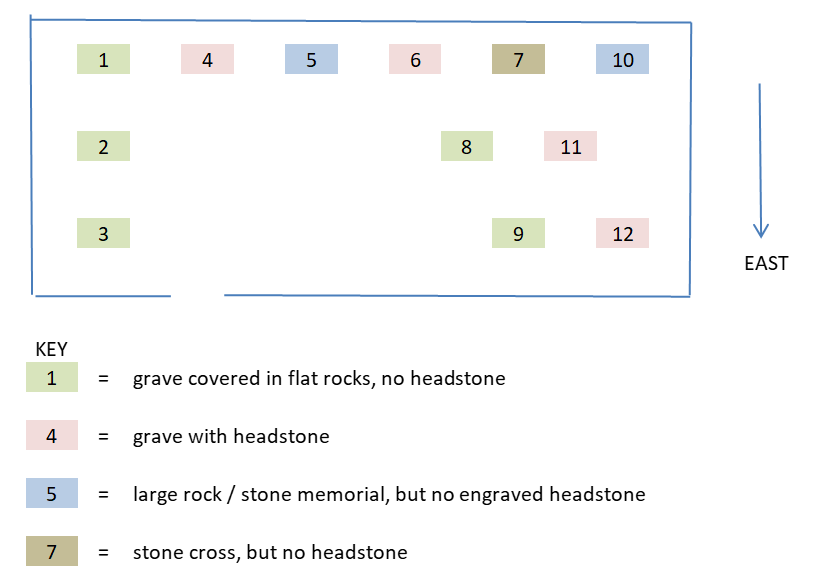

| Name | Date of Death | Details |

2 | P.H. Cumming, age 32 yrs. | 23 March 1896 | Headstone said: "killed in the Matabele Rebellion 23 March 1896. This had a marble upright slab 76 cms high. |

E.C. Edkins, age 27 yrs. | |||

John Carpenter | |||

J.A. Baragwanath | |||

4 | Graham Hunter Lundie | 18 May 1897 | Died at Belingwe, erected by his comrades of "C" Troop, BSAP. This had a cement cross 2.75 metres high. |

6 | Andrew Fraser | 9 May 1897 | Died at Mpateni, near Belingwe erected by his comrades of "C" Troop, BSAP. This had a cement cross 1,52 metres high. |

11 | Henry "Harry" Norval | 2 Nov 1918 | Headstone says: "wounded at Menin 22 Sept 1917" Website states: "estimated birth 1885. As Rfn was severely gassed in WWI; Died in the 1918 Spanish Flu Epidemic, Source: www.1820settlers.com/ |

12 | Alfred Wilson | 14 Oct 1928 | Aged 56 years |

In researching an article on the Loyal Women’s Guild and the Pioneer memorial crosses I used a grave register compiled by BSA Police Commissioner William Bodle. In his notes on this cemetery he states there was a marble slab headstone over grave 2, but this no longer exists, and that the cemetery on 13 May 1907 was neglected with a broken fence and two missing headstones.

Most of the graves on the plan (no’s 1,3,5,7,8,9,10) have no grave markers and are unidentified.

Rod Finnigan very kindly supplied further information on two of the BSAP Troopers from the pre-1903 nominal roll.

Andrew Fraser - BSAP No 242 attested on 13 October 1896 in the Matabeleland Division and died on 9 May 1897 at Mpateni.

Alfred Wilson - BSAP No 368 attested on 21 December 1896 21/12/96 in the Matabeleland Division and left of his own accord (no date given)

The cemetery site where many of the bodies were buried in a communal grave is south of the coach road, but also west of the stream and on the opposite side of the coach road from the destroyed remains of Edkins Store and a few hundred metres from the Filabusi Memorial site. There might have been several communal graves dug by the first police patrol as they brought in bodies from the various scattered sites which had been lying in the open from the end of March until the beginning of September.

Of the thirty-five names on the Monument killed on or after 23rd March 1896, twenty-nine are listed killed in the Filabusi district. The ’96 reports say Colin McDonald, or MacDonald was also killed in Filabusi, but then says he was killed with Henry Classen who is listed as killed at Makukupen [Essexvale] so I have omitted him from the total. It is not known, but it is likely that when the area was safe enough for the first police patrol to return, probably after the third Indaba at Fort Usher No 3 on 9th September, the remains of the bodies which had been left by Spreckley’s patrol unburied were collected and then buried in a communal grave/s at the old Filabusi cemetery site.

The ’96 Reports published by the British South Africa Company lists of all those civilians and military killed and wounded in Matabeleland and Mashonaland; however, the dates for those listed at Edkins Store are 24 March 1896, and for the remainder at Filabusi the 25 March 1896 or “end march.” Joseph O’Connor was the sole survivor, and nobody was alive when Spreckley’s patrol reached Edkins Store on Thursday 26 March, so I have changed them all to the most likely date of Tuesday 24 March 1896.

This is the complete list of all the names on the Filabusi rebellion memorial, the colours correspond with each panel. Those names marked with an * are very possibly buried in the communal graves at the old Filabusi cemetery.

Roger Howman recorded in his article that one of the communal graves was maintained by the local Lions Club and recorded the names of P.H. Cumming age 32, E.C. Edkins age 27, J.L. Carpenter, J.A. Baragwanath – killed 23 March 1897. [This should be 24 March 1896]

Edkins Store

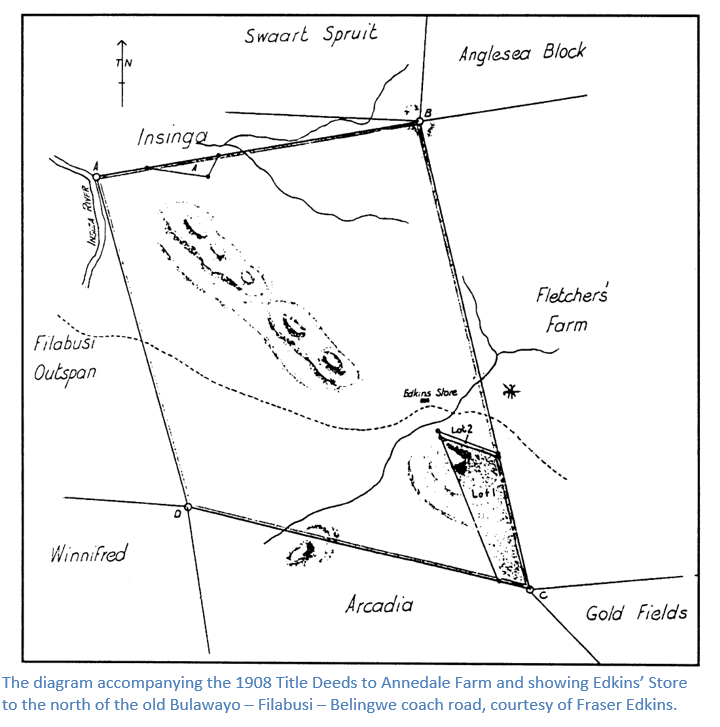

The store is positioned on the diagram with the title deeds to Annedale Farm to the north of the coach road and west of the small unnamed stream and we know that the store was completely destroyed on 23rd March with the Bulawayo Chronicle reporting on 28th March that when Spreckley’s patrol returned to Bulawayo that they had found “the store in ashes.”

Edkins Store seems to have been established from about 1894 as Fraser Edkins quotes correspondence dated 24 December 1894 from the Postmaster General in Salisbury requesting stores for a postal agency at Inseziva [Insiza] under the charge of E.C. Edkins and on the road between Belingwe and Bulawayo. An advert in the Bulawayo Chronicle of 18 January 1895 said: “E.C. Edkins & Co have opened a general store in the Filabusi District Umzeza (Insiza) River (Post Office for the District)” R.C. Smith’s Rhodesia a Postal History gives the following information:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Initially runners carried the mail to Bulawayo, but from the middle of 1895 the Zeederberg Coach ran from Bulawayo to Belingwe via Edkins Store close to the Insiza River, and Filabusi.

For some time in 1894 - 1895 Ebenezer Edkins was in partnership with Arthur Cumming; but this ended in later 1895 when Albert Baragwanath bought a half-share in the business and Arthur Cumming opened his own store 20 kilometres closer to Bulawayo. Orlando Baragwanath, his older brother, arrived back in Rhodesia in January 1896 and helped his brother at the store and with the two Cumming brothers and John Carpenter did some prospecting in the Filabusi area. Orlando Baragwanath later identified Albert’s body.

Fraser Edkins provides details of another advert in the Bulawayo Chronicle of 12 December 1896 from the executors of Edkins and Albert Baragwanath for the one year “lease of the property known as Edkins Store on Annedale Farm, Filabusi,” for £24 for the first year, with a right of renewal for a further two years at £48 per annum, and the assurance that: “the position of this store, in the midst of the numerous rich gold properties in the Filabusi district is such that, with good management, an enormous business will shortly be done.”

It appears that the lease of Edkins Store was taken up, possibly by Mr Kirkman referred to below, but as the Store had to be completely rebuilt, he probably chose a new site with the old site being considered too near the cemetery. However, it is clear the business was restarted as the note below indicates.

Botton’s Hotel and Store

Ian Carruthers supplied the following note from his cousin Oswald Botton: “The Botton’s Killarney Mine business prospered, this made it possible for Arthur Botton to acquire the stock-in-trade and goodwill of E. C. Edkins store that was situated in the same area, from its owner, an old hand Mr. Kirkman. Soon after Arthur took possession it became well known as “Botton’s hotel and store”. The hardy old prospectors who roamed the districts occasionally came into town to conduct their business affairs, generally ‘whooping it up’ on these visits until funds dwindled, compelling them to return to the simple life in the bush-veld. There were others who preferred the quiet and solitude of the country. Pubs were not for them, the glittering lights of cities-in-the-making had no attraction. The bush life, nonetheless, held an irresistible fascination for them all. They were accustomed to living spartan lives with the heavens serving as a roof over their heads and a layer of grass for a bed. Scanty meals were the order of the day, sadza being the mainstay augmented by what game they could shoot for the pot. The odd indigenous chicken purchased at a kraal was a welcome change of diet. Some of these tough old characters boasted a pack donkey and a firearm of sorts, the more affluent even employed a picannin to fetch and carry. The overwhelming majority lived a tough lonely life, relieved only by the occasional visit to a country hotel."

In 1968 Oswald Botton wrote the following account two months before his death: “Towards the end of 1905, my parents Arthur and Marion Botton were firmly established at ‘Botton's Hotel and Store’ and within a few weeks of being there, I accepted a job on the Celtic Mine a mile or so from home, as an amalgamator in the mill. The Manager of the Celtic Mine was a kindly and courteous old gent by the name of Tom Tooley and a close family friend. A most likeable, soft spoken and refined old man, who was incapable of saying an unkind word about anybody.”

There are no obvious remains of Botton’s Hotel and Store in the vicinity of the old Filabusi cemetery; but there are extensive old remains in the vicinity of the McLaren farmhouse, about 600 metres away to the south-east and this would seem to be the most probable site of Botton’s Hotel and Store.

This is probably the same site of the old Filabusi Hotel and Store which Leo Robinson, an early Native Commissioner, refers to as being near the Filabusi Memorial in the article: Memorials: 1896 Rebellion by C.K. Cooke in Rhodesiana No 22. July 1970.

Joseph O’Connor, the only survivor from Filabusi and his miraculous escape

Selous writes that he heard the following directly from Joe O’Conner in his Bulawayo hospital bed. About 7am on the morning of Tuesday 24 March 1896 Joe, Ivers and Ottens were having an early morning cup of coffee and discussing the problem of the thirteen mine workers who had run away from the Celtic Mine in the last few days. Ottens went off to see Arthur Bentley at the Police Camp near Edkins Store about 2.5 kilometres away to explain their labour problem; Ivers went to see how work was progressing on one of their shafts, and Joe made bread in the kitchen. He was smoking his pipe when Ottens’ dogs, Captain and Snowball, began barking furiously. So furiously that Joe thought a lion was in the camp and rushed to the door of the hut to see a musket being aimed at him. He retreated into the hut and the door became filled with amaNdebele.

Realising they had come to murder him, he rushed in amongst them and wrested away two knobkerries whilst being hit repeatedly with sticks and knobkerries, and fired at several times, before he burst through his crowd of assailants and stumbled into the Celtic Mine No 1 incline shaft about 100 metres from his hut and tumbled down the 45° angle “like a football.” Here he was attacked by ten miners coming up the shaft with hammers and drills; but beat them back with stones and when they retreated up the shaft, he hid behind some timbering in a drive about half-way up the incline shaft. A miner suddenly ran past and told the others that O’Conner was still alive and shortly after, some of his assailants were back with lighted candles and four with guns. Joe recognized two of them as “Candle” and “Makupeni” who had been working for them for nearly 18 months and had been trusted with camp rifles to hunt for game to supply the camp with meat.

He called to them asking what harm he had done them, to which they replied: “we’re going to kill you and all the white men in the country.” Although Joe could see them by the candle-light, they could not see him and were nervous to step into the drive for fear of being hit with a lump of quartz. The others at the surface were shouting: “what are you doing; why don’t you shoot the white man?” until suddenly those on the surface started shouting “amakiwa, amakiwa” meaning “white men” and his assailants all ran away. By the time they came back Joe had shifted position, but his attackers followed his tracks and threw two sticks of dynamite with short fuses into his new hiding place. Dynamite does slight damage in the open and Joe suffered no more injury, although he was nearly suffocated by the fumes and passed out before his assailants left, thinking he was dead.

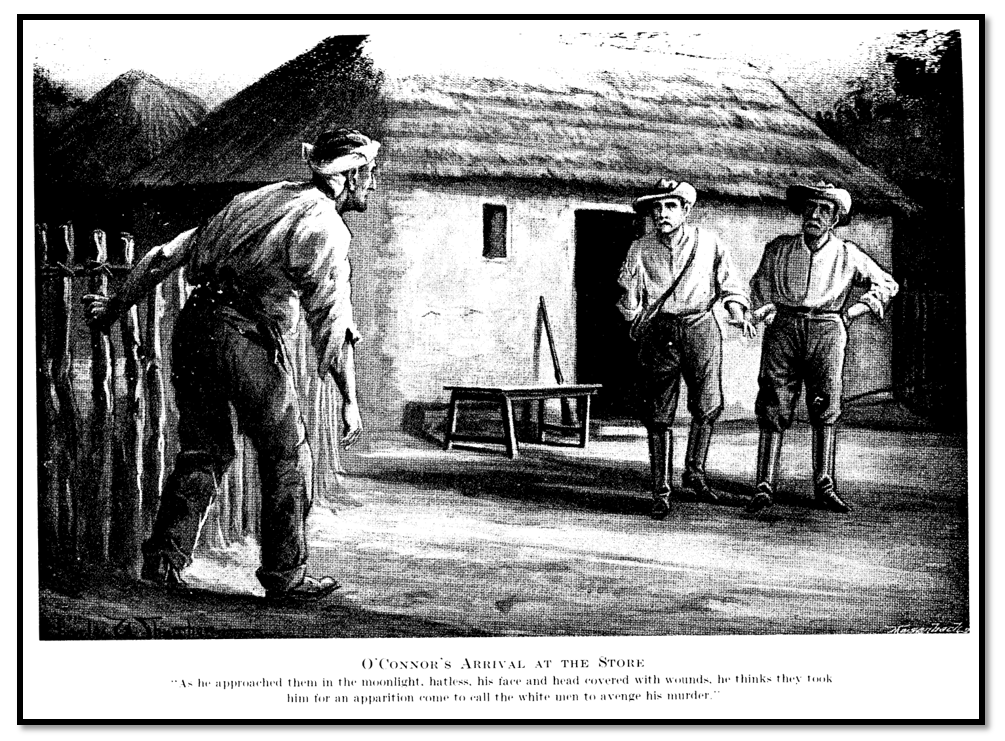

In the darkness some hours later, Joe O’Connor emerged from the shaft to see their Celtic Mine camp destroyed with all the huts burned down, but no sign of his assailants. He walked two kilometres to Nelson’s Camp which overlooked the Police Camp and, in the moonlight, saw the huts were still standing, but no movement. He went down to the unnamed stream between the Police Camp and Edkins Store where he: “wallowed in it like a pig.”

With his wounds bathed, he carefully approached Edkins Store, but saw it was burnt down and in the stillness could smell the scent of death. All alone he set off in the direction of Bulawayo and on reaching the Insiza River about 6 kilometres away lay hidden in a bed of reeds all night and for the next day, Wednesday 25 March. Dazed and light-headed, he walked by night and rested by day until he reached Dawson’s Store on the Umzingwane River at 11pm on Saturday 28 March; some 110 hours later, much to the surprise of Schultz and Judge who has been told by the returning members of Spreckley’s patrol that Joe O’Connor was dead.

Joe O’Connor probably never recovered from his experiences; at 26 years old his hair turned grey. A witness told Selous and Col. Napier that Joe’s brother, John O’Connor was hauled by windlass up the shaft where he was working and when he reached the surface was beaten to death whilst defenceless in the bucket; his cousin Edward White was killed with assegais, and his companions Ivers and Ottens at the Celtic Mine killed. According to Orlando Baragwanath he took no further part in any of the subsequent fighting and lived an immoral life until he was killed by a bolt of lightning four or five years later.

When Roger Howman interviewed Orlando Baragwanath “Orrie” in his hundredth year in 1972, he found him praising John Carpenter and dodging questions about Joe O’Connor. Finally he said that in their small Filabusi community, Joe O’Connor was the most disliked and despised character.

Arthur Cumming and Orlando Baragwanath questioned the amaNdebele who had been present at their killings to get at the truth about the death of their brothers. The amaNdebele all laughed at Joe O’Connor’s survival and said that at the time he had “behaved so badly, they had ordered the youngsters to kill him” which job they had botched up whilst escorting him to the Celtic Mine incline shaft, so that he managed to get away.

Leo Robinson, an early Native Commissioner, is quoted by C.K. Cooke in an article: Memorials: 1896 Rebellion in Rhodesiana No 22. July 1970 as saying: “O’Connor, whom I met in 1897/98, was attacked and practically left for dead by the natives after he got into a shaft [at the Celtic Mine] in the Filabusi district. He recovered his senses and walked up the Mzingwane River. When he got to Lulapa’s kraal (somewhere below the Matabele Sheba Mine) the natives wanted to murder him, but Lulapa (one of my Indunas in the early days) would not allow the “young bloods” to do so, but told O’Connor to continue up the Umzingwane River, until he got to the Tuli Road, near Dawson’s Store, and then take the main road to Bulawayo.”

Chief Maduna Nkojene like the other amaNdebele who were present at the killings was full of praise for John Carpenter. (This story was also verified by the three young African survivors who met Arthur Cummings) Carpenter was recovering from fever and still ill on Tuesday 24 March. However, he fought off the amaNdebele and when he had to evacuate Edkins Store because it was on fire, made for the nearby stream with the young Mashona servant boy whom Arthur Cumming later met and held out amongst the boulders in the stream bed. He told the young boy to crawl away and warn those at Weir’s Store whilst he taunted his attackers to attack him. All agreed “he died well.”

Acknowledgements

Roger Howman. Orlando Baragwanath: A Centenarian Pioneer of Rhodesia. Rhodesiana No 28 July 1973

T.V. Bulpin. To the Banks of the Zambezi. Nelson, 1965

F. Sykes. With Plumer in Matabeleland. Books of Rhodesia 1972

F.C. Selous. Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia 1968

C.K. Cooke. Memorials: 1896 Rebellion. Rhodesiana No 22. July 1970

F. Edkins. Ebenezer Crouch Edkins (1869-1896) The Edkins’ Store killings and Joe O’Connor’s wonderful escape. Heritage of Zimbabwe No 17, 1998. Pages 1-16

R.C. Smith. Rhodesia A Postal History. R.C. Smith 1967

Ian Carruthers for supplying info on O. Button. http://newsfeed.rootsweb.com/th/read/RHODESIAN-PIONEERS/2006-02/1140247893

I.J. Cross. Rebellion Forts in Matabeleland. Rhodesiana No 27. Dec 1972

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890-1897. Rhodesiana No 12. Sept 1965

Rod Finnigan for BSAP details