Home >

Matabeleland South >

An explanation for the Y-shaped rock art motifs found on Nottingham Estate in the Limpopo-Shashi Valley

An explanation for the Y-shaped rock art motifs found on Nottingham Estate in the Limpopo-Shashi Valley

Introduction

This article relies heavily on two articles by Geoffrey Blundell[1] and Edward B. Eastwood,[2] both experienced rock art researchers and authors who have written extensively on their research in the Limpopo-Shashi Valley. The articles are Re-Discovering the Rock Art of the Limpopo-Shashi Confluence Area, Southern Africa and Identifying Y-shape motifs in the San rock art of the Limpopo–Shashi confluence area, southern Africa: new painted and ethnographic evidence.

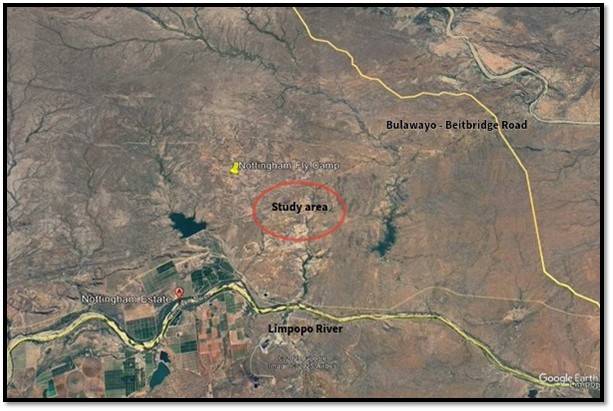

Many thanks are due to Byron Knott who patiently escorted Louise and I around the numerous rock art sites of Nottingham Estate and provided lunch and drinks on a sweltering September summer’s day. The general locality of the sites we visited is the area between Nottingham Retreat with its fishing dam and the Fly Camp at 22° 04´ 2.95" S and 29° 39´ 19.58" E

Location and Iron-Age background

The area covered in this article lies approximately 35 KM from the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashi rivers where the boundaries between Botswana, Zimbabwe, and South Africa meet.

Google Earth Image

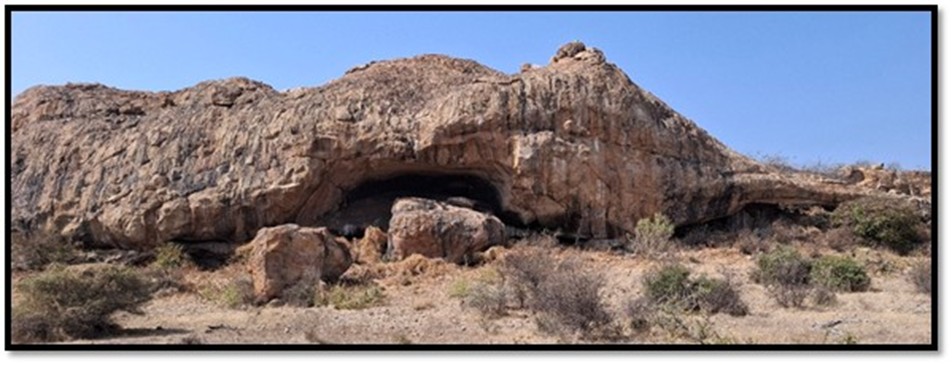

The area is composed of a series of deeply eroded ridges that run roughly parallel to the Limpopo River. Mostly cream-coloured, the ridges belong to the Tshipise Member of the Clarens Formation of Karroo sandstone. It is along these ridges that shelters - formed by water erosion or by subsidence from vertical and horizontal joint planes – are found containing the rock art.

General view of the Nottingham Estate landscape

Hyena Cave – Nottingham Estate

The area is very rich in plant life and this combined with the relative abundance of water from the Limpopo and Shashi rivers and their tributaries supports a wide variety of wildlife. This diversity has long attracted human settlement. Archaeology has established that the Zhizo culture inhabited the Shashe-Limpopo Basin, and parts of present-day Zimbabwe, Botswana, and South Africa, from approximately 900 AD to 1 000 AD. They are known as a farming and cattle-rearing community that also were involved in long-distance trade with the coast, trading ivory for ceramics and beads, and are known for their pottery and clay animal figurines.

A landscape rich in plants and wildlife

Around 1 000 AD the Zhizo culture with its capital at Schroda to the north-east of Mapungubwe Hill was succeeded by absorption or displacement by the K2 culture that flourished around 1 000 – 1 200 AD. Both are separate distinct phases of the Middle Iron-Age in the Limpopo-Shashi Valley

The K2 culture changed from one based on social ranking to a new culture based on social classes with a significant social stratification with its rulers moving to a physically isolated position that became based on Mapungubwe Hill and the beginning of the next cultural phase – the Kingdom of Mapungubwe. This was aided by its growing prosperity from cattle wealth and ivory from the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashi rivers that formed the basis of long-distance trade with the coast. In time this would be followed by the Great Zimbabwe and Khami cultures.

Late Stone Age Culture

Much less is known about their San hunter-gatherer predecessors. What is known is that “during the nineteenth century, for example, many of the region's hunter-gatherers seem to have fallen victim to the war between the Matabele and Tswana”[3] and “after this period of conflict, very few San groups were reported by European travellers in this disputed frontier territory.”[4]

Samuel Dornan[5] reported that groups of Hietchware San[6] were still in the Limpopo-Shashi Valley and that some lived in Tswana villages along the Motloutse and Shashi Rivers and are reported to have finally moved away from the Limpopo-Shashi Valley in the 1950’s after white farmers came into the area. Nick Walker reported in 1991 that they still lived along the Shashi river but had largely lost their identity and customs.[7]

But as Eastwood and Blundell state, “The paucity of information on hunter-gatherers of the LSCA[8] is unfortunate because at least 95% of the rock art images documented since 1992 are almost certainly San hunter-gatherer in tradition. Some images appear to have been the work of Bantu-speaking farmers…We argue that this rock art is unique in several ways and differs from the art of the Matopos to the north in Zimbabwe, and from that in the south-eastern mountains and southwestern Cape in South Africa. As we proceed, it will become clear that the rock art of the LSCA does indeed represent a clearly defined subregion.”[9]

Previous research into the rockart of the Limpopo-Shashi Valley

Eastwood and Blundell’s summary refers to Andrew Anderson who travelled the area in 1866 and illustrated the rock engravings that he found there. Only in 1952 did Clarence van Riel Lowe publish nine of the rock art sites in the area in a catalogue of rock art sites of South Africa. In 1960 Murray Schoonraad carried out the first major investigation into nine sites. He described fish and birds, as well as stylised female human figures and the Y-shaped motifs but did not carry out any further research. Others, including Alex Willcox, Willcox & Harald Pager, Cran Cooke and H. Simons carried out limited fieldwork on the South African and Zimbabwe sides of the Limpopo river.

Much more extensive work was carried by Eastwood through Palaeoart Field Services from the 1970’s with many of the previously documented sites being re-visited.

Rock Engravings

These are present in the Limpopo-Shashi Valley, Eastwood and Blundell identified five categories of engravings including schematic designs, animal motifs, animal spoor, cupules and cut marks, but were not included in our visit.

Rock paintings

Eastwood and Blundell identified three major categories of paintings including animals, human figures and Y-shaped motifs.

Animals

Amongst the animals the most commonly identifiable image was that of the kudu antelope (15%) with indeterminate antelope comprising the bulk of the images. Other identifiable animals included antbear, baboon, birds, buffalo, eland, elephant, fish, giraffe, hippo, hyena, impala, jackal, leopard, lion, locusts, mongoose, painted dogs, reedbuck, rhino, tsessebe, sable, warthog, wildebeest, zebra and fat-tailed sheep.

Kudu are usually painted in red ochre pigment, but also as finely detailed bichrome and polychrome examples. They noted that the polychrome images are usually larger than the monochrome ones. Also that the sheer numbers of kudu and their elaborate treatment indicate not only a connection with the rock art of Zimbabwe where the kudu also features predominantly, but that they had a similar role in the rock art as that of the eland further south.[10]

After kudu, the elephant was most common making up 11% (n=56 of 506) of animal images. They are usually painted in black pigment without ears or tusks and at least 60% of these elephant images have red dorsal lines.

Giraffe comprised 6% (n=31 of 506[11]) and also often included red dorsal lines. Most giraffe are red monochromes but several elaborate polychromes were recorded, some of which have red dorsal stripes extending from the base of the head to the base of the tail. This line may refer to the San people’s belief in the supernatural potency (n/om) of the animals, the giraffe being considered an especially potent animal.[12] However the authors noted that only at a few sites are a wide variety of animals depicted.

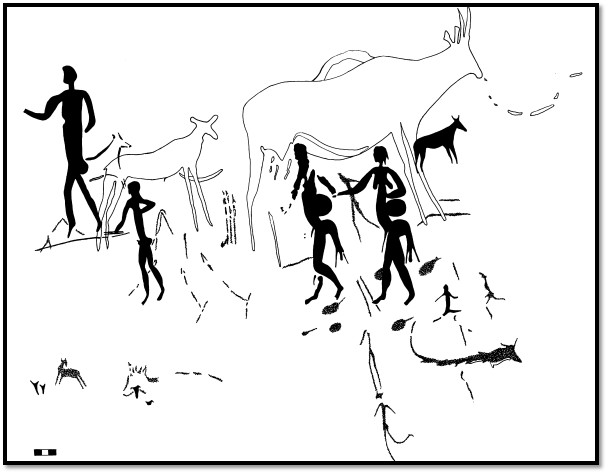

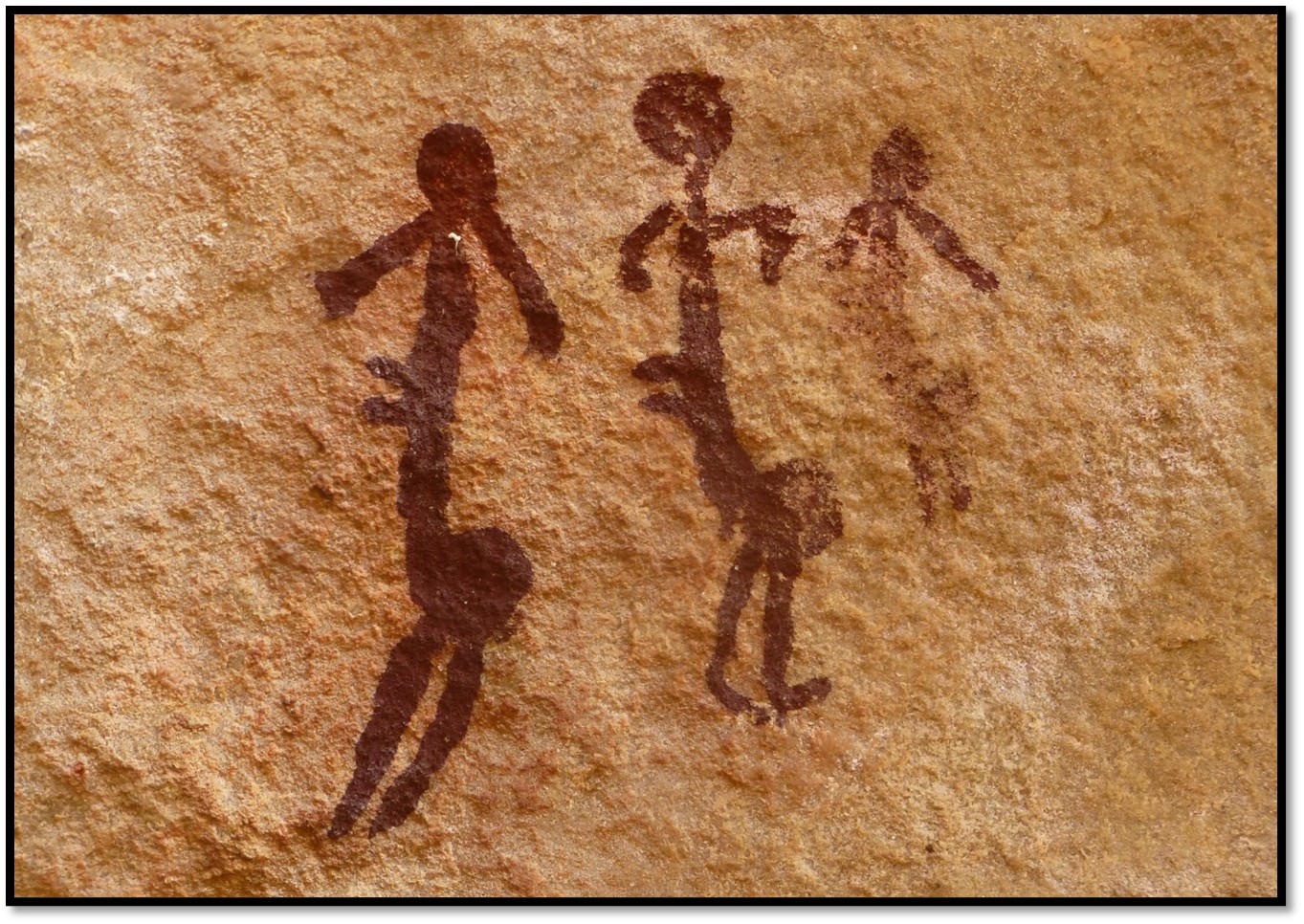

Human Figures

Both male and female figures were recorded although 47% (n=274) did not have primary sexual characteristics - penises for men and breasts for women. However Eastwood and Blundell speculate that the indeterminate figures may be male because they are slender and upright, as are those that are clearly male. When identifiable, women are usually shown with reverse articulation of the legs, exaggerated lordosis of the spine and breasts.

Women constitute 31% (n=182) of all human figures; males for 22% (n=128). This is an extremely high percentage of women when compared to other rock art areas of Southern Africa. In the southeastern mountains, women make up 2% of the human images. In the Cederberg 9.6%: at Tsodilo Hills 3.2% and in the Soutpansberg 1%.

Women are seldom painted with men and are generally portrayed in single-sex groups. The authors suggest the high number of women and the separation of men and women into gender groups may have been one of the primary underlying structures of the art. Some groups of men or women sometimes suggest dancing but for the most part they appear simply to be walking.[13]

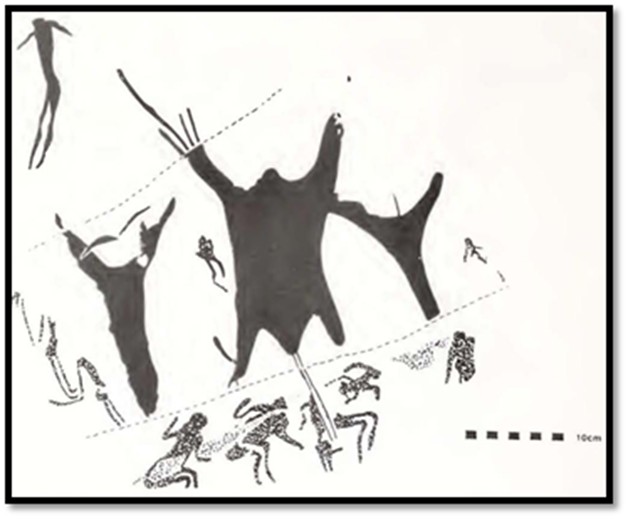

Y-shaped motifs

These are the most intriguing and enigmatic paintings and occur in over 60% of recorded sites[14] (n=85) Eastwood and Blundell state they are often found in a range of forms from a simple Y-shape to a 'spread-eagled' shape that resemble stretched out animal skins.[15]

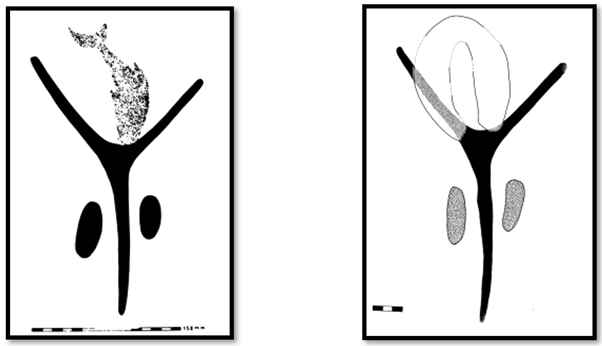

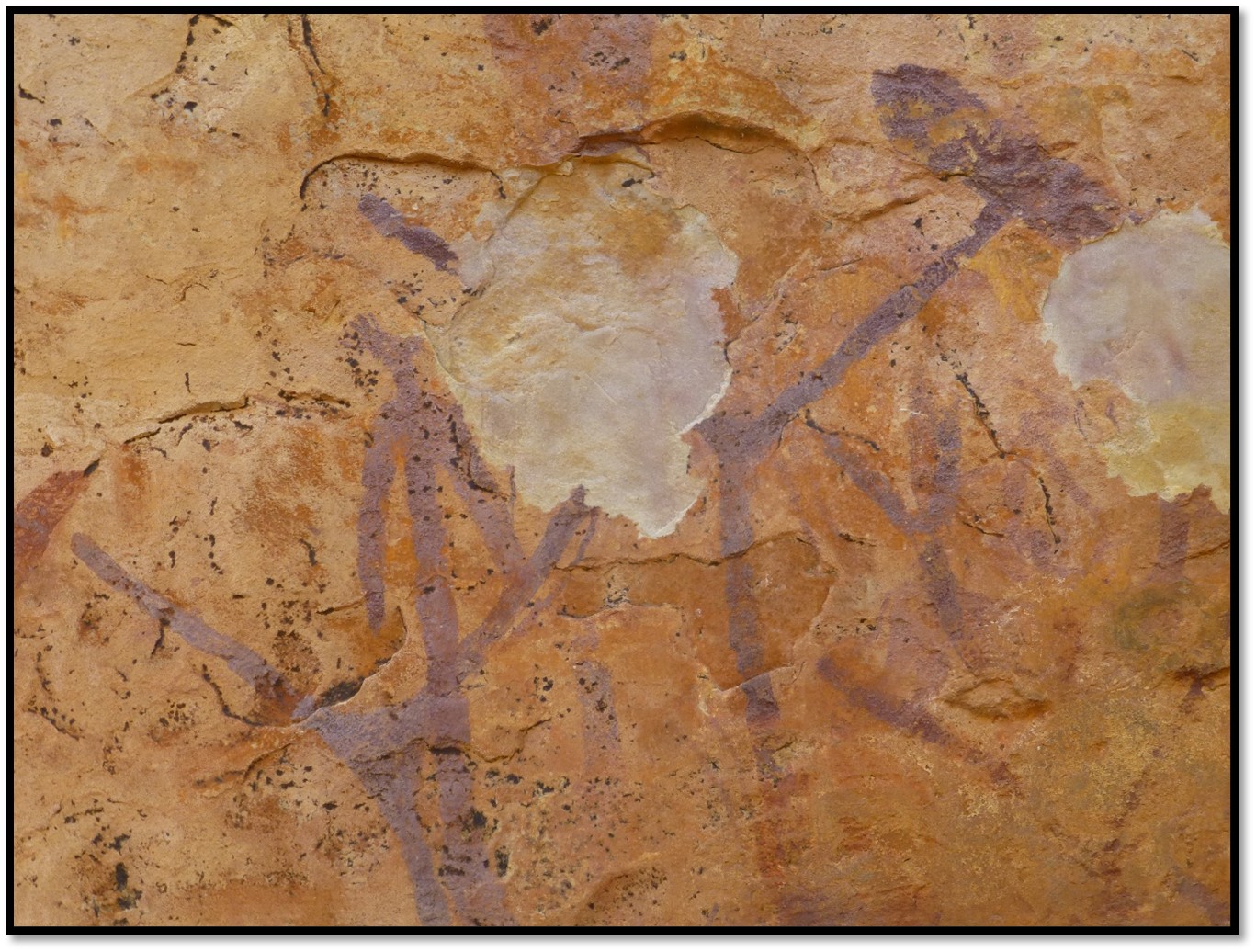

Typical Y-shapes and a 'spread-eagled' motif.

The 'spread-eagled' motifs are often juxtaposed with Y-shapes. The authors state the continuity in form between Y-shapes and 'spread-eagled' figures strongly suggests that they comprise a class of image, even though their significance may not be identical. In the past, the Y-shapes were interpreted as fish traps - they consider this explanation as unlikely because they are never immediately juxtaposed with depictions of fish.

All Y-shaped motifs so far discovered in the Limpopo-Shashi Valley are painted rather than engraved. The authors write, “Most commonly, they are painted individually in otherwise unpainted shelters or as apparently isolated images in painted shelters, but they are sometimes found over or under other paintings. In some cases they are grouped together in rows. Occasionally, these rows also have ‘spread-eagled’ images. Most Y-shape motifs are monochrome red; infrequently, they are painted in black or in black and white. In many cases straight lines are painted from both branches of the Y; occasionally, the lines end in an oval shape.”[16]

Harald Pager recorded them at 18 (out of 32) sites on the southern side of the Limpopo River and from a single site in the Soutpansberg. He suggested various possibilities — Khoi aprons or bags, or ornaments, but eventually based on one image with faded white paint that he interpreted as a depiction of a fish entering the Y-shape from above, he decided they were indigenous fish traps. Confirmation came from a fish expert who stated the two oval shapes were anchorage weights used to hold down the fish trap.

Pager’s published re-drawing of the ‘fish trap’ Blundell and Eastwood’s copy of the Y-shape

Blundell and Eastwood’s views of the same image under the varying light over a two-day period revealed that the ‘nose’ of the ‘fish’ extends over the red paint on the right fork of the Y and further white pigment to the left of the fish is superimposed over the left fork and forms an inseparable part of the ‘fish’ image.

They say that in this shelter and many others there are numerous white U-shapes, some inverted, which they believe are zebra spoor.[17] With one such shape immediately next to the supposed fish trap they conclude that the white pigment on the left fork of the Y is the left-hand side of one of these inverted U-shapes and that the ‘fish’ is the weathered remnant of the right-hand side. Clearly then the Y-shape is not a fish trap, but a zebra spoor superimposed over the Y.

The photo below taken at Nottingham Estate shows at least nine miniscule inverted U-shapes above the left-hand Y-shape and the right-hand ‘spread-eagled’ shape.

Inverted U-shapes above Y-shape and ‘spread-eagled’ shape, Nottingham Estate

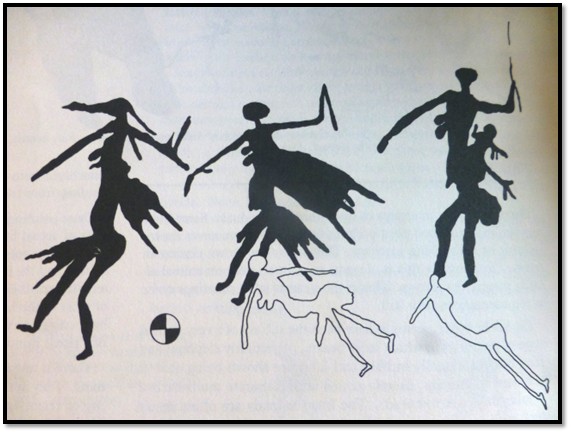

Y-Shaped motifs as articles of San clothing

The authors noted that Y-shapes are sometimes found in rows. Although they are generally quite scarce, the ‘spread-eagled’ motifs are commonly found together with Y-shapes and are rarely depicted independently. An important clue as to the identity of ‘spread-eagled’ motifs comes from the Makgabeng Plateau, 90 KM south of the Limpopo-Sashi Valley. The frieze includes two women who are partially clothed: an apron-like object hangs from each of their waists and covers their buttocks. Similar images are found throughout Zimbabwe. Sometimes these apron-like objects are painted with horizontal bars suggesting some form of decoration.

Tracing of the frieze from the Makgabeng Plateau

The authors believe these ‘spread-eagled’ motifs closely resemble actual San women’s back aprons in various collections, both having a single, small protrusion flanked on either side by longer, similar shapes. They believe the small protrusions on either side of actual aprons are the remains of skin left intact from the tail or head of the animal while the longer, flanking protrusions are the legs of an animal once it has been skinned. Importantly, the aprons worn by the women in the Makgabeng Plateau painting show a marked visual similarity to either the top or bottom part of a ‘spreadeagled’ motif. It is their belief that the ‘spread-eagled’ motifs depict San women’s aprons.

The aprons usually have chords on one set of the leg remnants that are used to tie the apron at the waist. The diagram above shows the tassels that would be used to tie the apron at the waist. This confirms the authors belief that the ‘spread-eagled’ shapes represent San women’s back aprons.

This leads the authors to conclude that the associated Y-shapes also represent some form of clothing, probably San men’s loincloths. These comprise a wide portion and two thinner straps that are attached to the upper part. These straps are tied around the waist while the wider part goes between the legs and is then tucked under the waist straps. The extensions from the arms of painted motifs bear a close similarity to tying cords of loincloths and the ‘leg’ of the Y is formally similar to the part of the loincloth that goes between the legs.

In some historical documents two oval forms are attached to loincloths and were reported by early travellers as hanging from behind a man’s buttocks and are used to sit upon. The two oval forms in the Y-shape drawings above probably represent these oval forms.

Image from Murehwa Cave, Zimbabwe of San women wearing aprons with the same details as the ‘spread-eagled’ motif of the Limpopo-Shashi Valley. From Peter Garlake (Image 54) The Painted Caves.

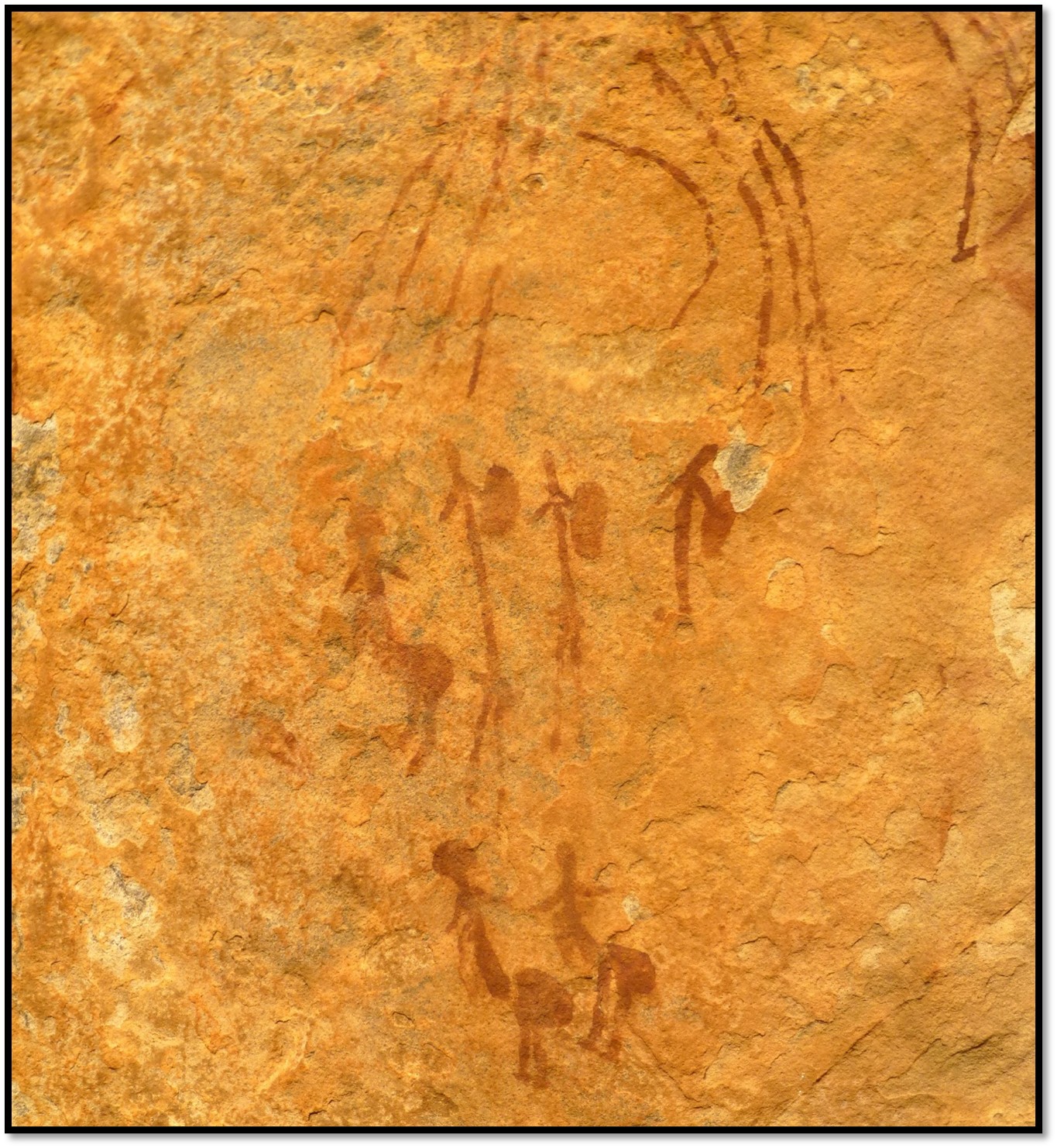

Late Stone-Age San images including Y-shapes on Nottingham Estate

Group of three San women and three males below possible grass shelters, Nottingham Estate

Y-shape above indistinct human figures, Nottingham Estate

Y-shape, Nottingham Estate

Faded Y-shape, Nottingham Estate

Faded Y-shape with indistinct shape to the right, Nottingham Estate

Very indistinct Y-shape with human figures below, Nottingham Estate

‘Spread-eagled’ motifs with associated Y-shape to bottom left, Nottingham Estate

Elongated Y-shape surrounded by faded human figures from the bottom left of the image above, Nottingham Estate

Y-shape (left) and two associated ‘spread-eagled’ motifs (one partially destroyed) with human and animal figures, Nottingham Estate

Three elongated Y-shapes with a superimposed male, Nottingham Estate

Monochrome Kudu doe, outline antelope-shape below, Nottingham Estate

Three monochrome females, crudely painted, Nottingham Estate

Bichrome Giraffe, Nottingham Estate

References

Edward B. Eastwood and Geoffrey Blundell. Re-Discovering the Rock Art of the Limpopo-Shashi Confluence Area, Southern Africa. Southern African Field Archaeology 8:17-27. 1999.

Geoffrey Blundella and Edward B. Eastwood. Identifying Y-shape motifs in the San rock art of the Limpopo–Shashi confluence area, southern Africa: new painted and ethnographic evidence. South African Journal of Science 97, July/August 2001, P305-8

Peter Garlake. The Painted Caves; An Introduction to the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe. Modus Publications (Pvt) Ltd, Harare 1987

Notes

[1] Rock Art research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand

[2] Paleoart Field Services, Louis Trichardt

[3] Re-Discovering the Rock Art of the Limpopo-Shashi Confluence Area, Southern Africa, P18

[4] F. Elton 1873. Journal of an exploration of the Limpopo. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society 42:1-49 and F.C. Selous 1908. African nature notes and reminiscences. London: Macmillan & Co.

[5] Dornan, S.S. 1975. Pygmies and Bushmen of the Kalahari. Cape Town: Struik Publishers.

[6] The Hietchware San were an eastern Khoe-speaking San group found in the Limpopo and Soutpansberg regions

[7] N. Walker 1991. Rock paintings of sheep in Botswana. In: Pager, S. (ed.) Rock art - the way ahead. SARARA International Conference Proceedings: 54-60.

[8] Limpopo-Shashi Confluence Area

[9] Re-Discovering the Rock Art of the Limpopo-Shashi Confluence Area, Southern Africa, P18

[10] N. Walker. 1996. The painted hills: rock art of the Matopos. Gweru: Mambo Press.

[11] E.B. Eastwood, C.J.H. Cnoops, B.W. Cnoops & V. Bristow. 1995. The rock art of Sentinel and Nottingham, Limpopo River Valley. Unpublished report for Sentinel Ranch (Pvt) Ltd and Nottingham Estates (Pvt) Ltd.

[12] L. Marshall, 1969. The medicine dance of the !Kung Bushmen. Africa 39:347-381.

[13] Re-Discovering the Rock Art of the Limpopo-Shashi Confluence Area, Southern Africa, P22

[14] Identifying Y-shape motifs in the San rock art of the Limpopo–Shashi confluence area, southern Africa: new painted and ethnographic evidence, P305

[15] Re-Discovering the Rock Art of the Limpopo-Shashi Confluence Area, Southern Africa, P24

[16] Identifying Y-shape motifs in the San rock art of the Limpopo–Shashi confluence area, southern Africa: new painted and ethnographic evidence, P305

[17] Roger Summers identified similar U-shape images as zebra spoor at the Bumbuzi site at Hwange in nearby Zimbabwe, P306

When to visit:

All year around

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: