Home >

Matabeleland South >

David Tyrie Laing and the near-disaster Matobo Hills engagement in the 1896 Matabele Uprising or Umvukela

David Tyrie Laing and the near-disaster Matobo Hills engagement in the 1896 Matabele Uprising or Umvukela

The accounts below are based primarily on David Tyrie Laing's book The Matabele Rebellion 1896 with the Belingwe Field Force, but supplemented with the accounts by Frank Sykes, Herbert Plumer and Robert Baden-Powell. At the end is a very personal and engaging account of the Inugu battle by Sergeant Charles Halkett who served in the Maxim Troop and was wounded.

It is unfortunate that all the texts are Euro-centric and there are no oral accounts by amaNdebele fighters who were present at the action. Their leaders certainly showed good tactical skills in using the natural cover offered by the Matobo Hills to their advantage and also good organisational skills in getting their warriors into position around the laager without being detected. Sergeant Halkett says the attack began when one warrior tripped and fired off his gun. Certainly once battle commenced the amaNdebele displayed a great deal of raw courage and strong discipline in facing down the seven-pounder gun and the Nordenfelt’s firepower.

This started as a hare-brained military plan with Tyrie Laing and his force being sent without any idea of the terrain they would be travelling through, with inadequate guides and with wheeled transport that was inappropriate for the narrow and rocky valleys that lend themselves to ambush positions and could well have resulted in a complete military disaster as at Isandlwana. Their superior firepower certainly saved them from a plucky and brave foe.

The Belingwe Field Force (BFF)

This is the second part of an account of the BFF. The first entitled The 1896 Siege of Belingwe, now Mberengwa as told by David Tyrie Laing is under Midlands Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The BFF was an ad hoc unit and only existed for the duration of the Matabele Rebellion or first Umvukela like others, such as Gifford’s Horse and Grey’s Scouts. It was established in Belingwe on 26 March 1896 and disbanded on the 30 September 1896. However the six months was a period of intense activity, the BFF incurred many small-scale engagements and numerous patrol incidents with ambushes on both sides as they crossed the Inseza district and then in the Matobo Hills.

Background to the battle – a sense of self-confidence

By June 1896 the military situation around Bulawayo was static after the various actions in April by Grey on the 17th, Macfarlane on the 19th, Bisset on the 22nd, Macfarlane’s second action on the 25th; all on the Umguza River around Bulawayo. The amaNdebele had been forced into a fight with Spreckley on the 6 June again on the Umguza River and the citizens of Bulawayo behind their laager defences were beginning to feel that the pressure had eased somewhat until more alarming news was received on 20 June with news of the breakout of the Mashona Rebellion / First Chimurenga.

As soon as the news reached Bulawayo plans were put in place to send reinforcements to Mashonaland. These included 440 men which was partly comprised of the 150 troopers who had left from Salisbury in Colonel Beal’s column in early April as a relief force to help the inhabitants of Bulawayo. Major Watts left Bulawayo soon after with 150 troopers of the Matabeleland Relief Force for Salisbury and was then followed by 70 Scouts under Capt. the Hon. C. White.

Importance of the Mambo Hills

Colonel Spreckley brought in news to Bulawayo that the child of the Mlimo, Mkwati and the Mlimo’s high priest, Siginyamabele were based in a shrine at Ntaba zika Mambo or Mambo Hills about 115 kilometres beyond Bulawayo and approached through Inyati Mission on the old Hunters road. Mlimo, the Matabele spiritual / religious leader is credited with fomenting much of the anger that led to this confrontation. He convinced the amaNdebele and Shona that the white settlers (almost 4,000 strong by then) were responsible for the drought, locust plagues and the cattle disease rinderpest ravaging the country at the time.

The Mambo Hills are probably just as rugged, although much smaller in area than the Matobo Hills, being about 65 square kilometres in extent. Some of the earliest murders of the Matabele rebellion were carried out here at West’s store by local Karanga people under Mkwati. [See the article Mambo Rebellion Memorial – with three oral history accounts collected by Foster Windram in 1936 and 1938 concerning the killings at West’s store under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Carrington ordered Lieut-Colonel Plumer to go on the offensive by attacking the Mambo Hills with a force of nearly 1,000 men.

Plumer’s force leaves Bulawayo on 20 June 1896

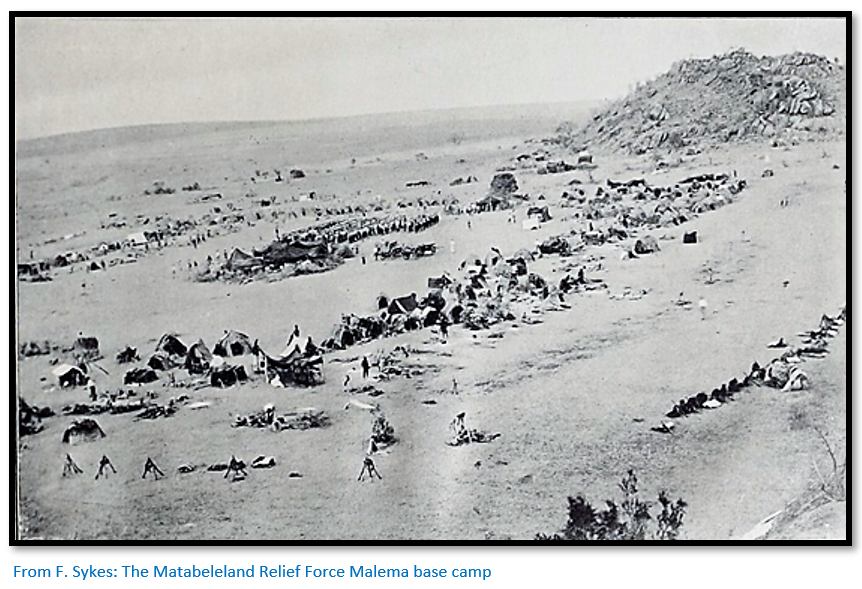

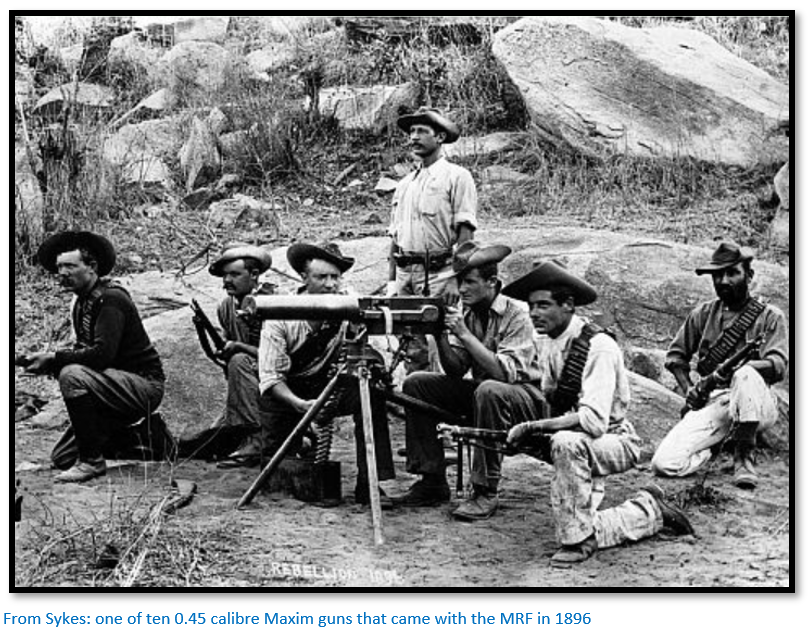

To prevent the amaNdebele forces from dispersing before their arrival, Plumer left Bulawayo on 30 June and planned to make a night march from Inyati and attack on 5 July 1896 at first light. The Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF) was a formidable force comprising 750 Europeans, 200 Cape Volunteers and two seven-pounders and a number of spectators including Cecil and Frank Rhodes, Vere Stent the journalist, Lieut-Colonel Baden-Powell (BP) and Weston Jarvis.

The MRF gets the benefit of current military intelligence in the Mambo hills

At Inyati the column met up with Jan Grootboom who had already spent the night in the Mambo Hills carrying out a reconnaissance and Plumer refined his attack plans based on Grootboom’s verbal intelligence briefing. The plan was for the infantry to lead and be joined up by the mounted men a few hours later. At West’s stores, Major Kershaw would press east with infantry whilst Plumer took the mounted troops and remaining infantry along the old Hunters road to the north east and to the base of the kopjes comprising the Mlimo’s stronghold. At first light on 5 July the forces would converge in a pincer movement to crush the rebels.

The MRF attack on Ntaba zika Mambo

Before dawn the cavalry had encircled the Mambo Hills and were following the Nsangu River south to cut off any retreat to the east in a movement that would take them around the Mambo Hills to join up with Kershaw’s forces. The Cape Volunteers under Major Robertson then moved directly into the Mambo Hills supported by European infantry and soon a series of skirmishes broke out. [For details see the article Battle of Ntaba zika Mambo, Manyanga or Mambo Hills under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The caves and hills of the Mambo Hills were strongly held and hotly resisted but Robertson’s Cape Volunteers and Kershaw’s infantry fought their way into the centre of the hills slowly driving the rebels backwards but meeting stiff resistance and taking casualties

Of all the military engagements that took place during the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela this was probably the most conventional although the battle soon deteriorated into a series of hand to hand skirmishes due to the limited visibility dictated by the difficult rocky terrain. Plumer’s force suffered eighteen dead and fourteen wounded and dispersed the amaNdebele from the Mambo Hills although Mkwati was not captured and took off for Mashonaland.

Little achieved in terms of military success

Similarly although many amaNdebele women and children and cattle were captured the bulk of the warriors had departed from the Mambo Hills for the eastern Matobo 100 kilometres to the south. As Herbert Plumer writes in his book An Irregular Corps in Matabeland: “No natives were found in Tabas-i-Mhamba or anywhere in the vicinity. The mounted troops came upon the spoor of a considerable number leading to the south-east and it is imagined that the bulk of the fugitives made their way into the eastern section of the Matoppo hills.”[i]

The military situation in mid-July 1896

Capt White had reached Fort Charter and was soon followed by Major Watts’ detachment and although the Mashona rebellion or First Chimurenga was still spreading the mounted infantry force under Colonel Alderson was rapidly moving up to Salisbury, now Harare.

The Bulawayo Field Force (BFF) had done good work in clearing the area around Bulawayo of an immediate threat and with more extended operations now beginning in the Matobo Hills General Carrington had decided to amalgamate them within the MRF.

A new camp was established on Usher’s Farm[ii] 10 kms from the northern edge of the Matobo Hills where it was clear the main force of the amaNdebele were located. Baden-Powell (BP) and Lieut Pyke under the tutelage of Jan Grootboom had made several reconnaissance trips into the Matobo Hills to establish the location of the various Chiefs and their warriors who were estimated to number about 10,000.

From the 14 – 16 July the MRF were busy refitting and replenishing supplies of stores and ammunition. It would be difficult to take wheeled Maxims into the Matobo, so two were converted for mule transport. Each Maxim had a mule carrying a gun saddle with gun and tripod and two boxes of ammunition, another mule took four boxes of ammunition with 150 rounds in each box, plus two mules were kept as back-ups. A ninth mule carried eight boxes or 1,200 rounds of additional ammunition.[iii]

General Carrington was determined to attack the amaNdebele with all the forces at his disposal

On the 16 July all the MRF officers climbed a kopje on the edge of the Matobo Hills to examine the apparently endless panorama of Kopjes to get an idea of the terrain they would soon be operating in: “there lay before us an apparently endless sea of koppies of various sizes, all more or less composed of huge granite boulders, in the interstices of which grew bush and scrub and separated from each other in most cases by only extremely narrow and torturous gorges.”[iv]

They soon grasped the difficulty they faced; if the Mambo Hills were 65 square kilometres in extent, the Matobo being 60 x 20 miles were over 3,000 square kilometres.

As soon as General Carrington arrived he had their camp moved to Usher’s Camp No 2 which was closer to the Matobo.

Belingwe Field Force arrives back in Bulawayo

Captain Tyrie Laing had arrived in Bulawayo on the 31 June following the successful night attack on Belingwe Peak and the daylight attack on Chief Senda’s stronghold [See the article The 1896 siege of Belingwe, now Mberengwa as told by David Tyrie Laing under Midlands Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

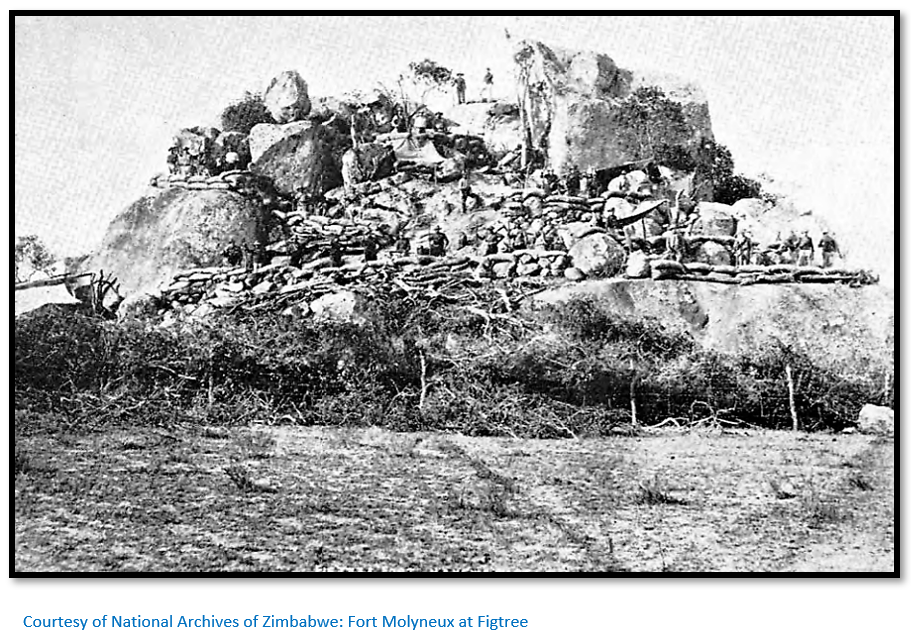

Fort Molyneux at Figtree

For some time there had been rumours that the amaNdebele intended to make an attack on Fort Molyneux.

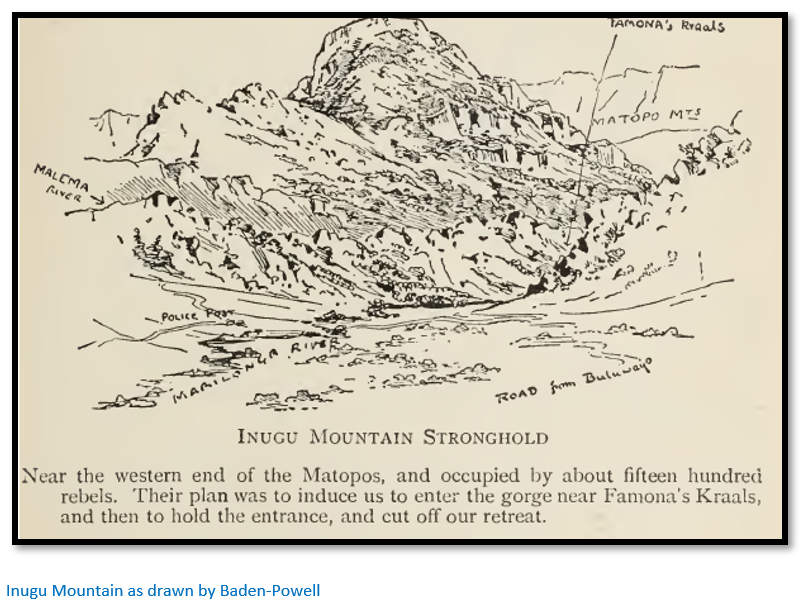

The rumours of an intended attack proved incorrect but Carrington considered the deployment of the BFF in that direction would cause a useful diversion to the planned attack on the Chilili valley and then they could co-operate by attacking Dhliso and Maholi, the husband of Famona, the daughter of Lobengula, who BP had heard was near Inugu Mountain in the western part of the Matobo Hills with a force of about fifteen hundred warriors.

On 12 July Tyrie Laing received orders to move his force to Fort Molyneux and took a ‘flying column’ of 70 men which reached Figtree the following day about 5pm. The fort as Peter Garlake[v] describes it was plagued with disaster; 90 sick horses, left there by Plumer in May, were driven off by the amaNdebele half an hour after he left and could not be recovered as the garrison had no saddles. In June orders were sent to the Sergt.-Major commanding to "Please report as soon as you have put your fort in such condition as to render it safe from catching fire." As this was apparently not done by the end of the month he and the entire garrison were replaced.

When Tyrie Laing and his BFF column arrived they found Lieut. Botha, the officer commanding was drunk and the corporal under arrest for shooting the sergeant. Botha was relieved of his command, but before returning under arrest to Bulawayo he managed to make matters still worse by cutting the telegraph wire.

Tyrie Laing and his men moved on about 5 kilometres where there was better water and grazing for the horses. On the 15 July instructions of the plan of attack were received and two days later the seven-pounder and Nordenfelt arrived under Lieutenant Butters.

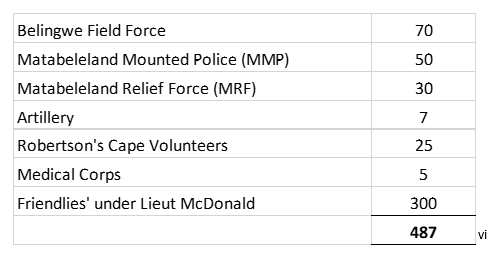

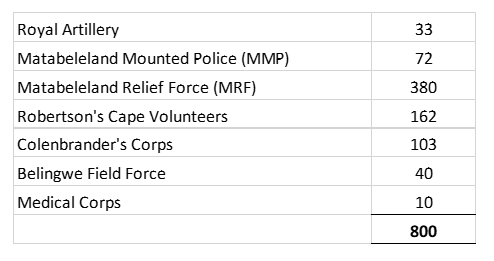

The strength of his force at that time was:

With support from the Nordenfelt [Halkett refers to a Hotchkiss] a Maxim and a seven-pounder.[vii]

On 18 July Tyrie Laing received a telegram saying the attack on the Chilili valley planned for the following morning was postponed and on the 19 July a despatch rider brought orders that he was to advance on Inugu and attack the following day and then cut off the retreat of any amaNdebele forces from the Chilili valley and then rejoin Plumer’s column by continuing through the Matobo Hills.

The main attack takes place up the Chilili valley

The plan was for Plumer’s main force to attack the amaNdebele forces under Babayane Masuku at Nkantola Mountain in the Chilili valley. On the morning of 19 July a reconnaissance party under Captains Coope and de Moleyns, Lieut Lowther and four scouts accompanied by thirty ‘friendlies’ under Purser went up the Chilili valley without encountering any opposition, but when they climbed the kopjes at the far end they were attacked and only managed to extricate themselves with some difficulty.

That evening an Matabeland Relief Force (MRF) column comprising:

At 10pm that evening the above force with two 2.5 inch guns, three Maxims and one Hotchkiss and three hundred ‘friendlies’ left Usher’s Camp No 2. The first 8 kilometres with open veld was crossed in the dark and without incident by 1am and the column rested in silence until 4:30am when the march resumed into the Chilili valley that was about 3 kilometres long and fairly broad although narrowing at points where it was commanded by steep-sided kopjes.

With the light of dawn enemy scouts were seen high up on the eastern side and dislodged with a few shells. The stronghold at the end of the valley was set amongst a labyrinth of boulders and caves and the huts were soon set on fire by the ‘friendlies.’ A heavy fire broke out and the ‘friendlies’ fell back with two wounded. The stronghold was then attacked by the Cape Volunteers and Colenbrander’s Corps supported by the two Maxims and the Hotchkiss and the defenders driven back with the loss of four Cape Volunteers killed and ten wounded.

Meanwhile, a mounted troop of the Matabeleland Mounted Police (MMP) and the scouts went ahead to try and find a route around the rear of the kopjes to cut off any amaNdebele retreat. However in passing through a narrow gorge in single file they came under heavy fire in which Sgt Frederick Warringham of the MMP was mortally wounded, Lieutenant Taylor of the Scouts slightly wounded and Colonel Rhodes had his horse shot under him. Only by early afternoon was the area cleared and the friendlies who had fled in the melee returned to carry out their duties as stretcher bearers for the wounded.

The withdrawal of the amaNdebele forces from the Chilili valley was only temporary and they soon re-occupied their former strongholds so the engagement cannot be seen as a victory for the MRF.

The Belingwe Field Force (BFF) task is to create a diversion in the eastern Matobo

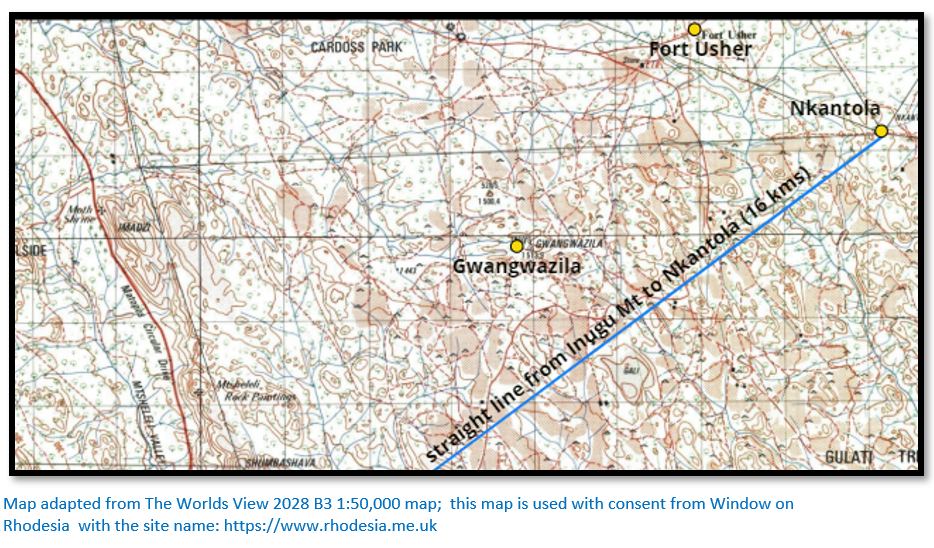

As outlined above Major Tyrie Laing’s mission was to march on Inungu Hill on the 19 July 1896 to outflank the amaNdebele and then on the next day to cut off the retreat of any of Babayan’s forces from the Nkantola Mountain up the Chilili valley.

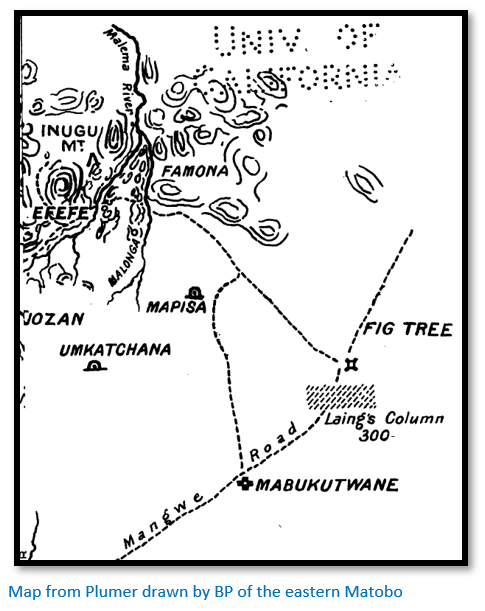

However, although only sixteen kilometres apart on the map, the physical terrain on the ground made this an impossible task. The map below shows the plan objectives were unachievable and only Carrington and his commanders Lieut-Colonel’s Plumer and Baden-Powell “BP” lack of local knowledge can explain away this military blunder. There is no evidence that any of the scouts or ‘friendlies’ were familiar with the numerous streams and granite ridges of this typically difficult Matobo terrain or knew the location of the Chilili valley and the Nkantola.

Lt-Colonels Plumer and Baden-Powell (BP) were General Carrington’s deputies and in his book BP writes: “Good preliminary reconnaissance saves premature wearing out of men and horses through

useless marches and counter-marches, and it simplifies the commander's difficulties, and he knows exactly when, where, and how to dispose his force to obtain the best results.”[viii]

Yet only a very brief reconnaissance was carried out by BP prior to Tyrie Laing and his force being ordered into the Inugu valley and he was not provided with any individuals who knew their way in this part of the western Matobo Hills.

The march to Inugu Mountain

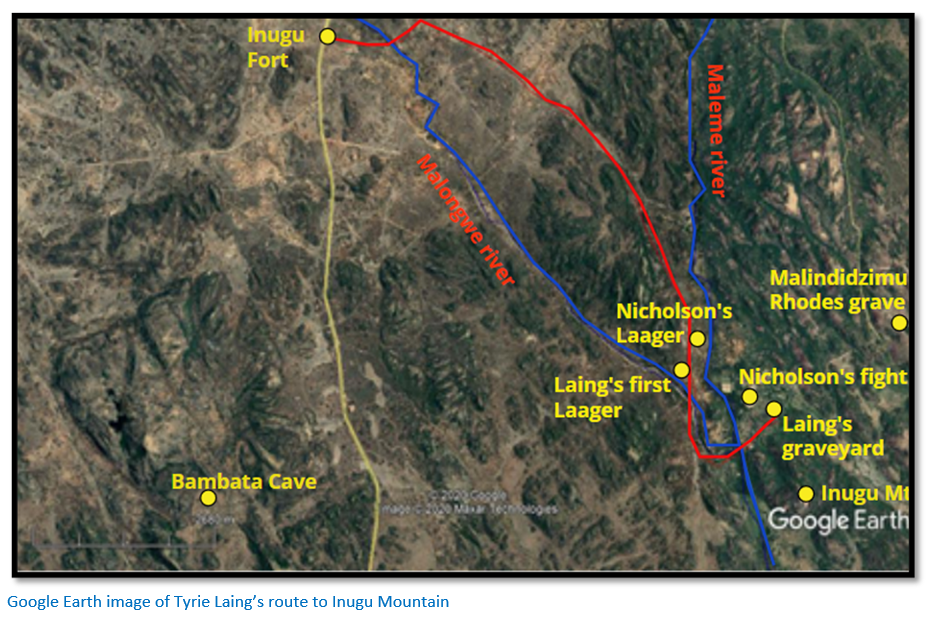

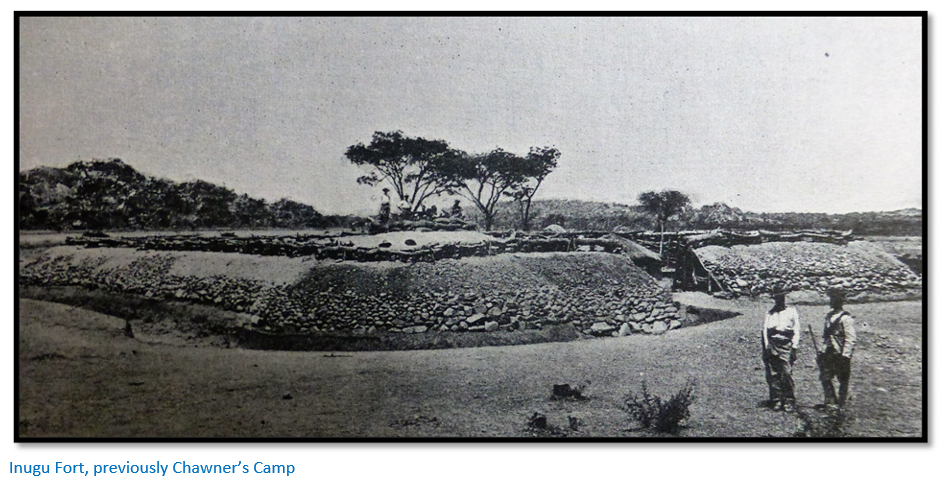

On the 19 July Tyrie Laing’s force reached Chawner’s Camp about 9am where the Malongwe stream crosses the present Kezi Road and they halted for an hour to refresh the men and horses and then followed the route outlined on the Google Earth map below and by noon were at the site labelled Laing’s first laager having travelled about 8.5 kms.[ix] Scouting parties were sent out but returned without any sign of the amaNdebele.

After some discussion with his fellow Officers Tyrie Laing decided to move up closer to Inugu Mountain. He writes: “The class of country we had to advance through now was most difficult and dangerous for an attacking force”[x] as they were forced to advance through a narrow valley covered in dense bush and cross the Malongwe stream and then the Maleme river all the time under a line of rugged hills. This section of 2.5 kms took much longer to travel as drifts needed to be made for the wagons and guns and it was only by nightfall that they were in a far from ideal laager position under Inugu Mountain dominated from the heights.

Sentries were posted and the men lay down in “skirmishing order” around the laager and about 20 metres in front of the wagons. The ‘friendlies’ built a thorn scherm[xi] against the rocks about 130 metres away and “every precaution was taken to guard against a surprise and I believe every man present expected an attack.”[xii]

The night was windy with clouds drifting over and several times the sentries reported seeing movement in the rocks above the position, but no alarm was given. In fact, the Mmabatho and Igapo regiments were already in position close by led by the Induna’s Mabiza and Maholi who were awaiting Dhliso’s regiment before attacking.

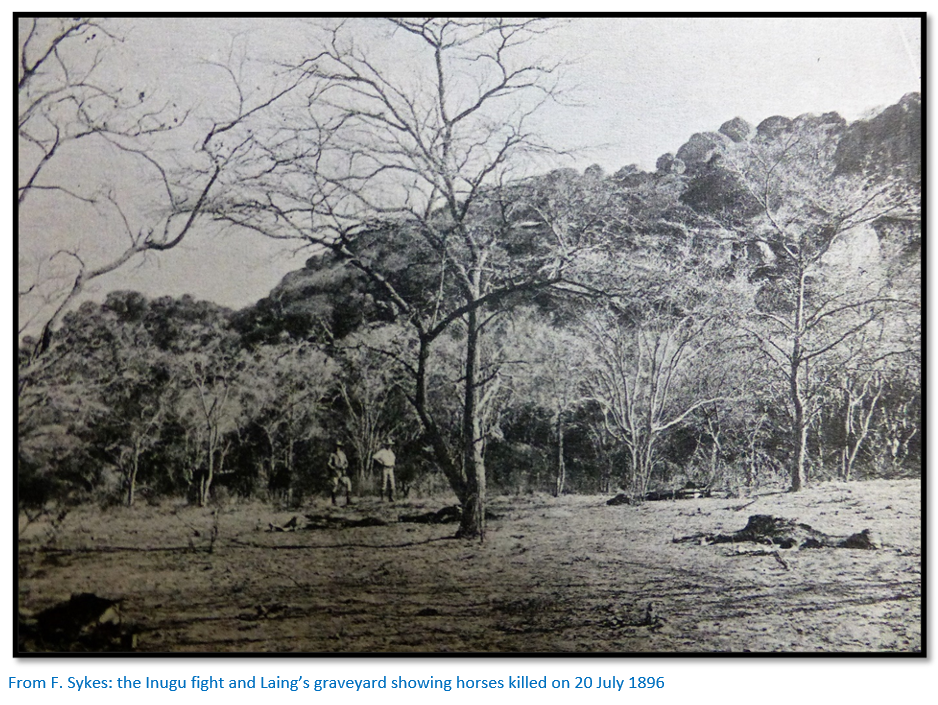

Inugu battle on 20 July 1896 at Laing’s graveyard

At 4am Tyrie Laing had ordered stand-to and as it gradually began to get light the mess orderlies were allowed to fall out and make coffee. With the dawn objects about 50 metres away could be seen and at 5:30am the “boot and saddle” was sounded and the last note had barely faded away when the first rifle shot was fired from above followed by a cacophony of shouting and yelling which preceded an AmaNdebele charge.

Tyrie Laing dropped his coffee mug and shouting “stand to arms” rushed to the rear face of the laager where he found the men kneeling with their rifles and Sgt Money crouched over the Nordenfelt. “All were anxiously watching the rapid advance of a yelling mass of rebels who were evidently vying with each other to get to the laager first, sending out deafening shouts to cheer themselves on and frighten us, firing off their rifles as they ran.”[xiii]

Tyrie Laing called to the men to keep steady and not fire on the pickets who were running into the laager and firing on the attackers as they came in. The order was given to open fire and the first volley checked the attackers and allowed the pickets to get in safely. The attackers then halted about 40 metres away waiting for their reinforcements to catch up whilst they kept up a steady fire on the laager.

Within the first two minutes Tyrie Laing saw two of his men killed and one wounded within a few metres of his position. The brunt of the attack was on the MRF under Lieut Butters and D Troop of the MMP under Lieut Bell. They kept up a steady fire, firing from behind their saddles on their attackers who were being reinforced from their rear and showed signs they were about to charge closer. Sgt Perry turned the seven-pounder around and was loading with case shot as their charge began.

The attack got within 20 metres, although some warriors fell only five metres away, before the seven-pounder opened up with case shot at point-blank range. The amaNdebele took huge punishment and when one of Tyrie Laing’s troopers stood up and shouted “are we to go back to the wagons” and had hardly got the last word out before he fell dead, shot through the head and Tyrie Laing rallied and steadied the men by ordering them to advance 10 metres, lie down as flat as possible and keep up the fire. Lieut Butters and a young volunteer Percy Hare dashed forward and inspired the troopers to do the same.

Second and third rounds of case shot from Sgt Perry with the seven-pounder, the hammering away of the Nordenfelt and steady fire from the rifles took their toll and gradually the amaNdebele broke away and took refuge in the bush and rocks on the laager’s right flank. Here they were exposed to E Troop and the MMP under Lieut Carney who kept up a continual fire at them.

This first attack had taken place at the rear of the laager and was meant as a diversion for the main attack from the front. However they had first to attack the ‘friendlies’ who although they broke at once and rushed into the vlei or under the wagons served to delay the impetus of their attack and gave Captain Hopper time to train his Maxim and allow a steady and destructive fire on the attackers as soon as the ‘friendlies’ had cleared the front.

If the amaNdebele on the south side had made an attack at the same time it might have been all over, but the delay meant that when they attacked it was against a machine gun and rifles.

Both sides then settled down to a short range rifle duel which lasted for an hour and a half; one amaNdebele called Hukutsa killing four of the defenders before being shot from his tree and eighteen horses and mules being killed. Tyrie Laing managed to steady his forces through his example, threatening those ‘friendlies’ hiding under the wagons to come out and chase away the amaNdebele attackers in the vicinity of the laager. As soon as a party of amaNdebele congregated and was spotted the seven-pounder came into action until gradually they slipped away and the firing died down by 8am.

Dhliso’s impi joins the battle

Just as Tyrie Laing was ordering the force to inspan with the intention of moving down the valley to attempt to join-up with Plumer’s force in the Chilili valley Lieut McDonald in command of the ‘friendlies’ reported a fresh impi approaching from the left front. The Maxim and seven-pounder were trained on the edge of the bush through which they were rapidly approaching.

No sooner had they appeared at the edge of the bush then the leading ranks crouched down as they waited for those behind to close up and began their war chants. Their leader began to shout to the amaNdebele behind the laager and the dialogue went on until Tyrie Laing ordered the seven-pounder to open fire on them. The first shrapnel shell fired by Sgt Perry exploded in their centre ranks and Captain Hopper opened fire with the Maxim.

This new force scattered under the heavy fire diving for cover behind rocks and seeking shelter in the dense bush and then retreating about 700 metres under a tree whose top could just be seen from the laager with the ‘friendlies’ who had a better view providing information on the numbers that had gathered there. The first seven-pounder shell exploded above the tree and the second about 20 metres from it sending the warriors scattering for cover.

Tyrie Laing writes: “Our force was just sufficiently weak to encourage the rebels to attack it and sufficiently strong to beat them off thoroughly” although the outcome could have been very different. At one point Tyrie Laing watched Dr Anderson and his assistants at work with over 30 dead and wounded lying at the medical position and who: “seemed to be oblivious of everybody except a devotion to his duty." He was with the wounded, bandaged their wounds and always had a cheering word for each one.

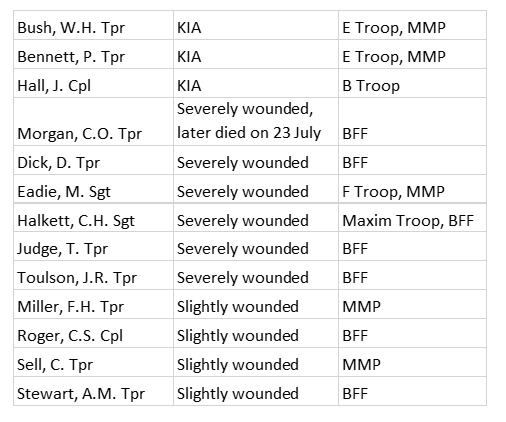

Killed and wounded at Inugu Mountain, Laing’s graveyard on 20 July 1896

The names of those Killed In Action are commemorated on the Fort Umlugulu Memorial [See the article 1896 Rebellion Memorials under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The ‘friendlies’ had fifteen wounded and twenty-seven killed and missing.[xiv] Eighteen horses and three mules were killed; with two horses and three mules wounded.

AmaNdebele casualties are unknown as they took their killed[xv] and wounded with them, but the action ended for them with Induna Mabiza being given the name: “the spoiler of the white man’s breakfast.”

The march continues in hopes of meeting Plumer’s force

The column inspanned and moved forward to try and locate an entrance to the Chilili valley but halted at 10am when water was found and breakfast prepared. The valley here was just 100 metres wide and within half-an-hour the scouts had reported amaNdebele forces moving in the direction of what was thought to be the Chilili valley.

The column moved on at 11am and made laager at a good location about 13 kms further on without the native guides ever locating the entrance to the Chilili valley.

Once the laager was secured the bodies of their dead comrades were buried in a single grave marked by a large cairn of stones. Three star shells were fired off to indicate their position but went unanswered.

From a good observation position in nearby hills during the night the scouts and ‘friendlies’ reported that at 3am on 21 July a large number of amaNdebele to their north were moving from the hills towards Fynn’s Farm and they were followed shortly after by a group of cattle, women and children moving in the same direction. These Tyrie Laing took to be those retreating from Col Plumer’s attack.

21 July – the column returns to Chawner’s Camp

Patrols and scouting parties went out after first light but nothing was spotted. The column moved forward about 2kms before Lieut McDonald rode in to report he had lost all faith in their native guides’ ability to find the entrance to the Chilili valley.

Tyrie Laing called his officers together and a decision to return by the way they had come was made and Chawner’s Camp reached shortly after sundown where they laagered for the night. Within an hour the sentries reported a large patrol approaching and a bugle sounded the general salute. Lieut-Colonel Baden-Powell made some notes and left for Usher’s Camp No 2 at once with his two squadrons of mounted men.

Baden-Powell’s account of finding Tyrie Laing

“During our attack yesterday morning we had heard Laing's guns banging away in a very lively manner in the distance, so that we had expected, on returning to camp, to get some news from him, but none came. We accordingly sent off some native runners to go and find him and to bring back information in case he should yet be among the mountains and we also sent a mounted patrol down to where his camp should be had he been successful and returned into the main valley of the Malema River.

But we could learn nothing of him; the natives returned and reported that he was cut off by the enemy from all power of communication. Naturally this began to make us feel somewhat anxious as I had already reported on the danger of the gorges in the neighbourhood of the Inugu and of the knowledge the enemy had of their tactical strength. So this evening the General desired me to take a strong patrol of a hundred men and go and find Laing.

We left camp soon after dark and followed the Malema valley in the moonlight until we were in the pass in the mountains which led down to the Inugu. My idea was to move through the outlying hills to strike the spoor which Laing had made in going into the hills and simply to follow that track until I found him. Even to strike the spoor one had to pass through some very nasty country, parts of which were in occupation of the enemy but as their main strength would now be collected against Laing and those that were left behind would probably be asleep, I did not expect much opposition on their part.

At length we successfully struck the spoor, but to my great surprise and delight we found it was quite fresh spoor, leading outward away from the mountains, and it very soon brought us to within sight of his camp-fires; so sounding a few trumpet-calls as we went in order to show that we were no enemy we made our way into his camp about eleven o'clock.”[xvi]

Return to Usher’s Camp No 2

The following morning about 11am an ambulance wagon and escort under Capt Beresford arrived with Dr Sutcliffe to assist Dr Anderson with the wounded and the column was back at Usher’s Camp No 2 by 3pm.

In camp he met General Carrington who congratulated him. Tyrie Laing writes that “The fight at Shangani and Bembesi during the campaign of occupation in 1893, were in my opinion, mere flea-bites compared with Inugu.”[xvii]

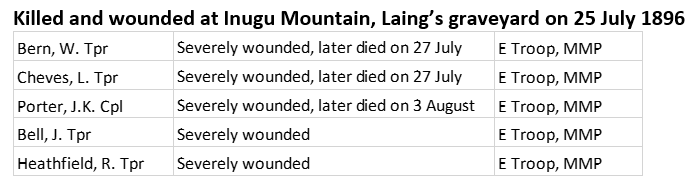

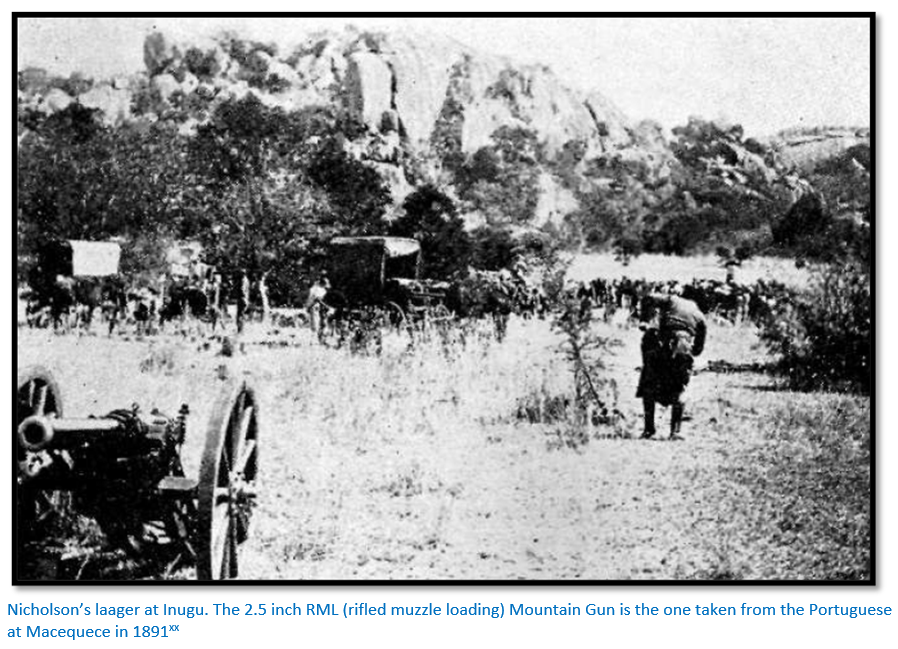

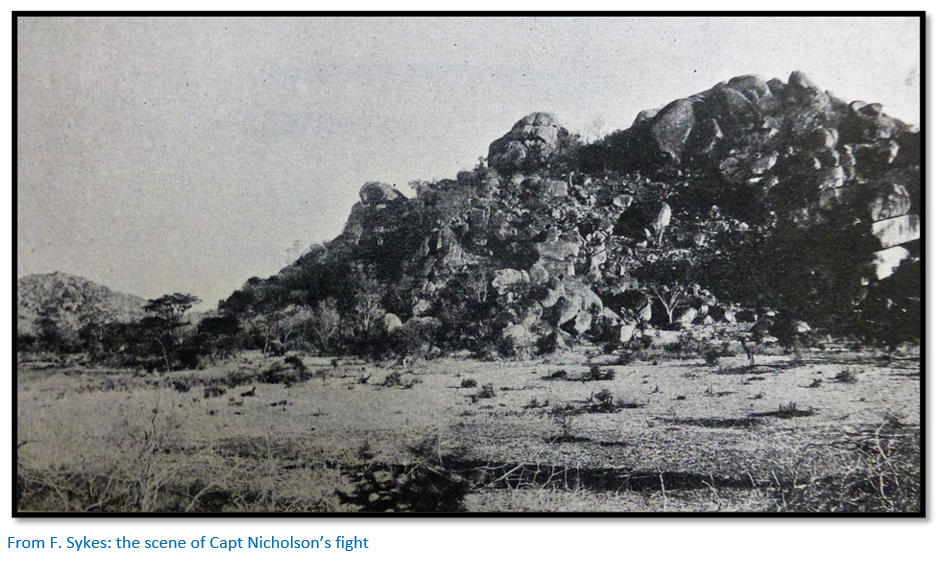

Nicholson is sent to the Inugu valley

Tyrie Laing makes no mention of Capt J.S. Nicholson’s follow-up action in his book, but Lt-Col Plumer decided that Tyrie Laing’s set-back needed addressing and the amaNdebele needed to be taught a lesson; so on the evening of 24 July Nicholson was sent with 250 Troopers and 200 of Johann Colenbrander’s Cape Volunteers, two seven-pounders and two Maxim machine guns to storm Inungu and defeat the forces of Mabiza, Maholi and Dhliso.

They camped at Chawner’s Camp and took Tyrie Laing’s route towards Inugu gorge but laagered for the night on the west bank of the Maleme River a mile south of Inugu Mountain at the site marked as Nicholson’s laager on the Google Earth map above.

On the 25 July the troops advanced in skirmishing order across the valley to attack the kopjes on either side of the Inugu gorge. As they were approached shots rang out from the heights and a Maxim and Hotchkiss[xviii] were quickly run up to the mouth of the gorge to provide covering fire as the troops moved into the gorge.

Here they came under a heavy raking cross-fire from an invisible enemy and suffered four casualties before Nicholson decided the position was unassailable and abandoned the attack, the amaNdebele reportedly losing two men.

Colenbrander’s Cape Volunteers managed to storm the broken kopje on the right-hand side of the Inugu gorge but were unable to dislodge the amaNdebele from amongst the broken boulders and caves.

Killed and wounded at Inugu Mountain, Laing’s graveyard on 25 July 1896

Two Cape Volunteers were killed and four wounded. Bern and Cheves are commemorated on the Fort Umlugulu Memorial [See the article 1896 Rebellion Memorials under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

As Sykes states: “the particular object of the visit was no doubt to teach the rebels in that neighbourhood a lesson, but it was found that they were not as amenable to instruction as they might have been.”[xix]

Both Tyrie Laing and Nicholson were taught a tactical lesson that knowledge of conditions on the ground and ambush tactics had an important role in any fighting in the Matobo Hills and that modern military methods and superior firepower would not necessarily tip the balance in favour of the aggressor. The amaNdebele had learnt to their cost the firepower of the Maxim gun in 1893 and were prepared to alter their tactics by harassing the columns rather than full-frontal attacks.

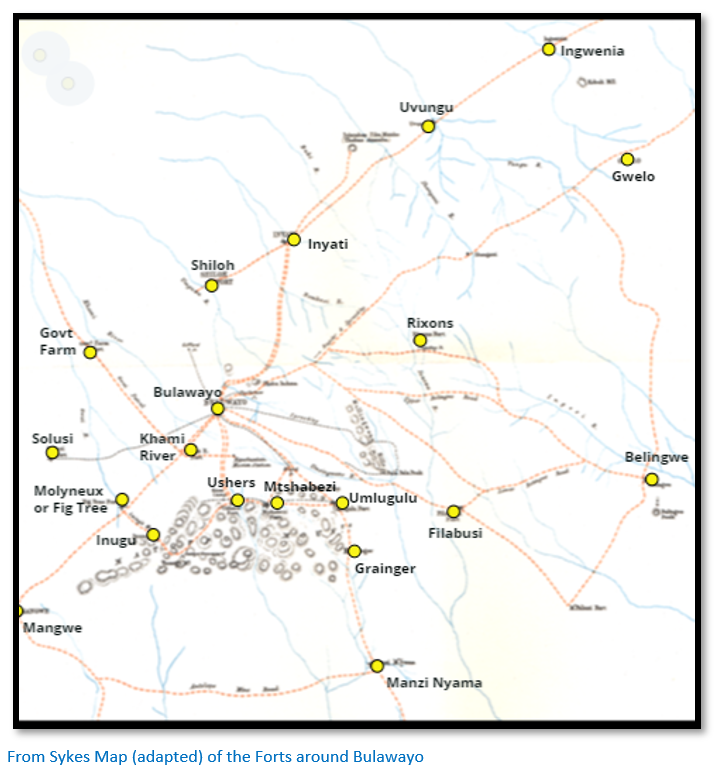

A ring of forts was established around the Matobo Hills

The military brains soon realised that any attempt to subdue the amaNdebele in the Matobo would require a much larger force than was present and that it could not be done with the existing transport and supplies. Any further military assaults would probably result in a heavy loss of life for both Europeans taking part and for the amaNdebele who would be unable to plant their gardens in the early summer because of the fighting and face food shortages.

A ring of forts would be established to defend the principal entrances into the Matobo Hills whilst the British South Africa Company under Rhodes resorted to political negotiation with a peace treaty as the end result.

Minor forts between Mangwe and Bulawayo such as Forts Dawson, Marquand, Halsted and Luck have not been included on the above.

Fort Inugu

Plumer writes that a few days after Nicholson’s action at Inugu he was sent back to begin the construction of a fort on some open ground facing the entrance to the Inugu valley. He chose the site of Chawner’s Camp, a former MMP site and after laying out the lines and starting the work returned to Usher’s Camp No 2 leaving a garrison of 25 Troopers and 25 Cape Volunteers to complete the construction.

Tyrie Laing and the BFF ordered to take supplies to Belingwe

Captain Frankland had been attached to Plumer’s column in the attack on Babayan’s stronghold at the Nkantola and being back earlier had seen to the overhauling of the BFF wagons and loading of supplies.

Once the shoeing of horses was complete, their provision convoy left on 26 July going via Ntabazinduna for signs of any amaNdebele activity, but none was found. On this day and the next the communications with Bulawayo were by heliograph.

By evening of the 29 July they laagered on the east bank of the Inseza river 80 kms from Bulawayo.

Towards sundown on the 30 July two despatch-riders brought instructions to keep a sharp lookout for amaNdebele moving east from the Matobo Hills.

On the 31 July Tyrie Laing sent seven wagons under Lieut Caldecott onto Belingwe and moved the mounted men in the cover of darkness under a large hill where they had a good view of the surrounding countryside. There they waited for two days sending out scouts but without encountering any activity.

By the 3 August they were at Posselt’s Farm 20 kms from Belingwe and Tyrie Laing left the column with a small escort and rode into Belingwe to find they were not in dire need of provisions as they had been led to believe at Bulawayo.

At Belingwe, now Mberengwa on the 5 August 1896

Captain Stoddart who was in charge of the Belingwe garrison reported all was quiet except for the district under Chief’s Wedza, Mazezeteze and Mondi where there was believed to be a strong amaNdebele presence. [For details of the earlier attack on Belingwe Peak see the article The 1896 Siege of Belingwe, now Mberengwa as told by David Tyrie Laing under Midlands province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Leaving Lieut Yonge in charge at Posselt’s Farm with A Troop, Tyrie Laing decided to assault Chief Mazezeteze and Mondi’s kraals and taking E Troop, Captain Stoddart’s infantry and 30 Cape Volunteers on the 7 July crossed the Utshingwe river to the north of Belingwe and by evening laagered within 3kms of both Mazezeteze and Mondi’s kraals. AmaNdebele were seen in numbers on the peaks but showed no aggression.

The assault on Chief Mazezeteze’s kraal

Next morning the force moved up under the hill, 3kms long by 2 kms wide and 150 metres high in parts, in which Chief Mazezeteze’s kraal was located. The top of the hill was very broken up with granite boulders and caves from which the amaNdebele shouted down in a defiant manner.

Captain Stoddart and E Troop were sent around to the southern end of the hill with orders to storm the kraal and drive the amaNdebele from their positions; Captain Frankland was sent with a patrol of mounted men to send in reports as the operation proceeded.

Lieut Beasley was sent to a point 500 metres from the eastern flank of the hill to cut off any amaNdebele who might leave for the Bungwe Hills, running parallel to, and about 5kms east [i.e. on the Great Dyke Range]

Lieut Howe with 20 of the Cape Volunteers was sent to the north of the hill.

As E Troop reached their allocated position Sgt Perry began to shell the positions on the hill where the amaNdebele had been seen. Shortly after intense firing indicated E Troop were advancing and after fifteen minutes a large column of smoke revealed that the first kraal had been burnt and the southern portion of the hill cleared. Warriors could be seen moving to the northern side of the hill as E Troop advanced.

Soon the sound of rifle fire broke out on the northern side of the hill and shortly after midday Captain Frankland rode in to say that the amaNdebele were in a strong position and that the seven pounder was required to force them from their cave stronghold. Trooper Woest had been killed and was lying up close to their caves.

Sergeant Perry was sent forward with the seven-pounder to shell the caves and the body of Woest was soon recovered. Attempts were made to persuade the defenders to surrender by offering them their freedom and liberty, but no replies were received and the attempts were given up.

As it was almost sundown the troopers were ordered back to the laager.

The following day Trooper Woest was buried a kilometre west of the southern end of the mountain and a large cairn of stones erected over his grave.

The column moves onto Mondi’s kraal

On the 10 August they moved south east to Mondi’s kraal which was found deserted; the Chief and his followers had left for Chief Wedza’s kraal. The kraals were burnt and the column moved back to the north bank of the Utshingwe river where they laagered for the night.

The Belingwe district is visited

The following day a drift was made across the Utshingwe river and Posselt’s Farm reached by midday where Lieut Yonge had little to report.

The column then moved south east in the direction of Belingwe Peak but the scouting patrols reported no signs of activity.

On the 12 August at Little’s Camp 8kms south west of Belingwe the wagons were dismantled and refitted, the horses re-shod and Tyrie Laing took the opportunity to take a few mounted men and inspect the principal mining camps in the district. The Great Belingwe, Bob’s Luck and Wanderers’ Rest mines had all been looted and their equipment destroyed, but no amaNdebele were spotted.

The column moves from Belingwe

On 19 August the column moved out from Little’s Camp intending to cut a new route to Inseza across the Utshingwe river as it was thought this would make the rugged country to the north more accessible and several new drifts were cut across the river.

Lieut Yonge with a detachment of mounted men and a Nordenfelt were left at Posselt’s Farm.

On the 25 August Chief Tandodzie’s stronghold was attacked but the small force of about 30 amaNdebele abandoned the kraal after two shells had been fired and disappeared.

The column was laagered on the east bank of the Shangantope stream when a grass fire was lit by the amaNdebele to drive them out but proved to be more of an annoyance than a threat.

Death of Sgt Perry

On the 27 August they were laagered at ‘Finger Kop’ 8kms east of Inseza waiting for a small convoy of wagons under Lieut Wilson from Belingwe with supplies for the column. He reported all was quiet but brought news from Lieut Caldecott and Lieut Jackson, acting Native Commissioner that a number of Chiefs had come in to surrender. Their surrender was accepted and they were instructed to return to their kraals keeping their arms and to send messages if there was any activity in their districts.[xx]

Sgt Perry who had done a magnificent job with the seven-pounder at Inugu went down with enteric fever and died in the early morning of the 29 August and was buried the same day under a Marula tree 160 metres south of ‘Finger Kop.’

Cumming’s Store

The column moved on after the burial service to the ruins of Cumming’s store at the Inseza Hills and laagered. The marks of the fighting which had taken place here before and during Maurice Gifford’s rescue of those that had been besieged here were still visible in the remains of the walls. Some of their dead had been buried hurriedly under fire and Tyrie Laing’s men ensured there were all properly buried.

Establishment of Fort Rixon

On the 30 August they crossed the Inseza Hills laagering at the foot of the western slopes and met up with Capt Warwick who had a detachment of police with him to establish a post at Rixon’s Farm this leading to the establishment of the present-day Fort Rixon.

Warwick told Tyrie Laing of the peace talks that were then taking place [See the article The Matabele Uprising or First Umvukela Indaba Site (Rhodes Indaba Site) under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] and he decided to take the column back to Bulawayo.

By 1 September Tyrie Laing was back in Bulawayo and reported to Carrington.

Disbandment of the Belingwe Field Force

On 7 September Carrington issued general orders disbanding a portion of the BFF and the resignation of Capt Tyrie Laing who was given the honorary rank of Major, Capt Stoddart and Lieuts Wilson and McCallum.

Captain Hopper arrived back from the Belingwe and Inseza districts on 29 September and the force was disbanded the next day. They marched into Bulawayo and paraded in front of the Administrator, Earl Grey who addressed them and thanked them for their gallant services. General Carrington also sent his appreciation of the services the BFF had provided and for their conduct in the field.

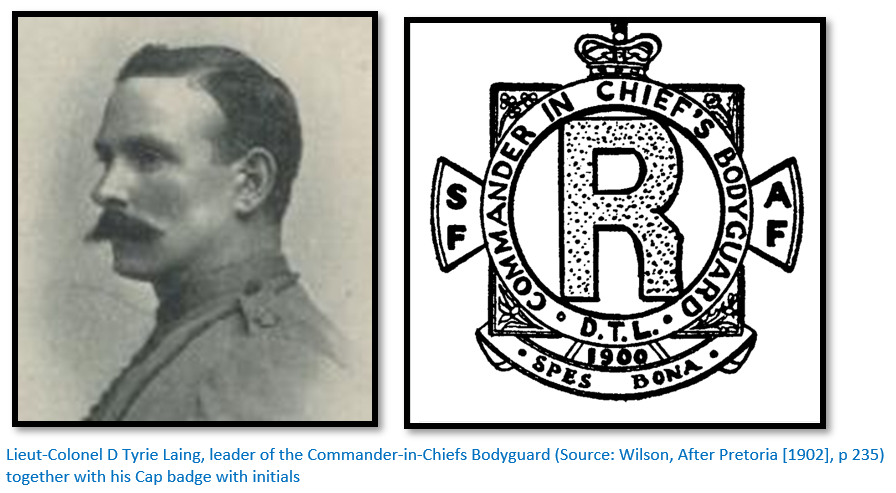

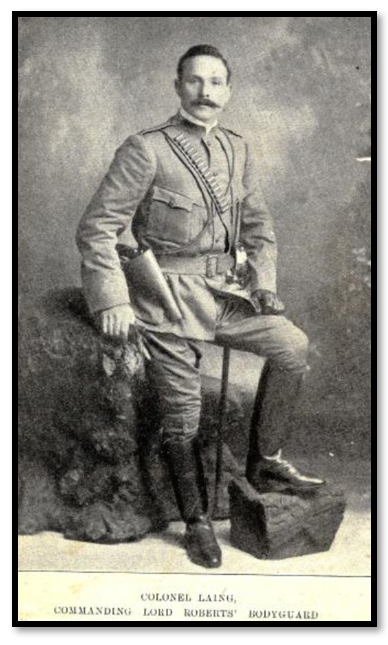

Death of David Tyrie Laing in the Anglo-Boer War

The Corps of Commander in Chief's Bodyguard was raised in Cape Town by Lord Roberts as a personal bodyguard on 31 January 1900 and placed under the command of Tyrie Laing. Initially numbering about 100 men, all of whom were colonials and in the main picked from existing South African 'regular' volunteer units, in November 1900 the unit became a fighting regiment to be called 'The Bodyguard' with a strength of 570. This was soon increased to 1,000 men equipped with two pom-poms and two machine-guns.

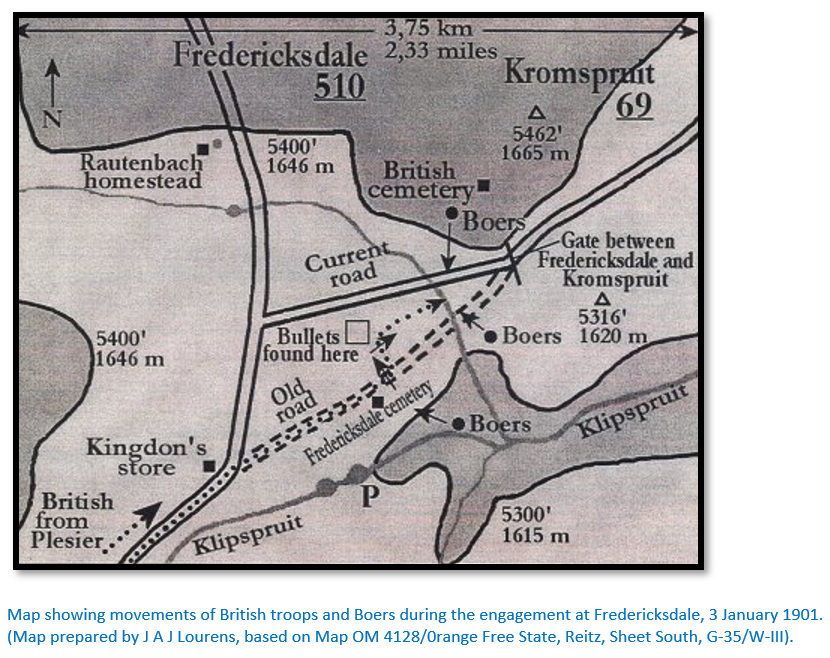

This account of his death is from the article by Janet Lourens and Steve A Watt called Fredericksdale 3 January 1901, A little known engagement of the Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902 published in the Military History Journal Vol 14 No 3 - June 2008

Colonel White sent Lieutenant-Colonel D Tyrie Laing with 120 of his Commander-in-Chiefs Bodyguard ahead to reconnoitre the route from Lindley to Reitz. The Bodyguard left Plesier[xxi] marching eastwards along the valley of the Klipspruit in the north-eastern Orange River Colony towards the Liebenbergsvlei River. Since it was high summer and the road ran alongside the spruit, the grass would most probably have been long and have provided cover for the enemy. Despite this, 'the party, regardless of rules and experience, was in close formation and without even ground-scouts' (Grant, 1910, P 55). From Plesier they marched about 6 km across the farms Helpmekaar and Spijtfontein before reaching Fredericksdale.[xxii] Here they would have passed the burnt-out store of the Englishman, Stephen Murray Kingdon.

Only two weeks previously, British forces, implementing Kitchener's scorched earth policy, had arrived at Fredericksdale, the farm of George Frederik Rautenbach, who was away on commando (SRC, Vol 90, P 86) In an interview recorded many years later, his daughter, Susanna Magdalena, who had been a young girl of ten in 1901, related how her family's possessions had been set alight and how she, her mother and three sisters had been loaded onto wagons and taken to the concentration camp in Winburg. She also told of seeing Kingdon's store ablaze as they passed (Patriot, March 1998, P 8)

It was 3 January 1901…As they marched along, Laing's men would have passed the old Fredericksdale cemetery on their right…south of the cemetery, the ground falls away towards the Klipspruit while the old road ahead of the Bodyguard curved gently north-eastwards, descending gradually towards the drift on the tributary of the Klipspruit. With consummate skill, General Philip Botha, elder brother of Generals Louis and Christiaan Botha and father of General Manie Botha, exploited these natural features to ambush the approaching Bodyguard. Botha, whose commando consisted of about 80 burghers of the Kroonstad Commando, deployed a number of his men along the Klipspruit where they were hidden from the approaching Bodyguard by the fall in the ground and by the long summer grass. Anticipating that the British would move off the road to their left to gain protection from the shoulder of land dividing the valley of the Klipspruit from its tributary, he placed another group of burghers on the hillside to the east, where they would have an unimpeded view of the enemy.

Everything worked according to plan and shortly after passing the graveyard, the Bodyguard was subjected to a volley of rifle fire from the direction of the Klipspruit. The troops barely had time to recover and regroup to the left of the road when a 'perfect tempest of bullets' (Wilson, 1902, P 235) ripped into them from 550 metres away on the rising ground to the east of the drift. Laing was one of those wounded in the initial attack but managed to maintain control of his men. He mustered his troops with the intention of launching a counter-attack but his efforts were stymied when another group of burghers, judiciously deployed by Botha on higher ground to the north-east, opened fire. The fury of the exchange left behind a wealth of Lee-Metford and Mauser bullets which were later unearthed by Casper Bester and his nephew, S.C.C. Bester who, between 1920 and 2006 lived and farmed on the part of the old landholding of Fredericksdale, now known as Bridgerule.

Botha, having foreseen that Laing might seek assistance from the main column under Colonel White, which was only 6 km away at Plesier, commanded the burghers who had launched the initial attack from the Klipspruit to cross the road and take up positions at the rear of the Bodyguard. Laing then surrounded on three sides by Botha's commando, was faced with the option of continuing his defensive action or surrendering. He decided to fight on, probably in the hope that Colonel White's column would eventually come to his assistance.

In an effort to strengthen his defensive position, Laing ordered his men into the bed of the tributary where the eroded banks of the spruit to the north of the drift provided some cover. They put up a brave and determined defence which only faltered when Laing was shot dead with a bullet through the heart. The Boers pressing ever closer poured a deadly fire into the defenders. At this critical juncture, Lieutenant Bateson courageously dashed out of the fray, mounted his horse and rode through the encircling enemy, taking the news of the Bodyguard's plight to Colonel White. White immediately sent a relief force, but, by the time it arrived, Laing's men had surrendered and handed over their arms to the Boers, who had already left the scene (Wilson, 1902, p P35)

The South African Field Force Casualty List records that five men - Lieutenant H.H. O'Flaherty, Corporal Phillpot (22202) and Troopers J. Hett (22699), T. Foy (22431) and D. Kileher (22705) - were taken prisoner but were later released and re-joined the Bodyguard.

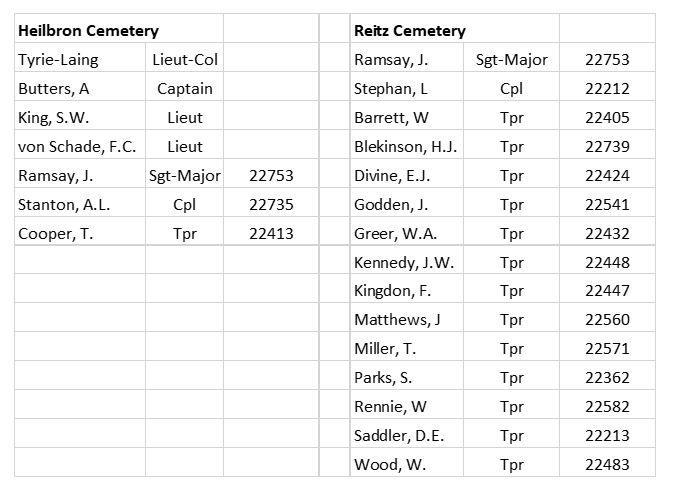

Casualties

Altogether, 21 officers and men of the Bodyguard, including Lt-Col Laing, were killed or mortally wounded. While the injured were evacuated to Reitz and Heilbron, the dead were buried close to the scene of the action to the north of the road and against the boundary between the old Fredericksdale and Kromspruit (see map above) J.J.G. Bester, then a young man in his thirties, recalls that in August 1965 he and four or five of his labourers exhumed their remains in the presence of a British official. Bester remembers that after working throughout the day they had exhumed the remains of about eight soldiers in a mass grave and one man buried at an angle of 90° to his colleagues. All the dead of the engagement were eventually re-interred in the heroes' acres at either Reitz or Heilbron.

A further thirteen men of the Bodyguard suffered serious wounds while twelve received minor injuries (South African Field Force Casualty List, P 101-2; Monuments in the town cemeteries of Heilbron and Reitz)

On the Boer side, only 29 year old Christoffel Johannes Smit died…Where he was buried and how many of his fellow burghers were wounded remain unknown.

Early life of David Tyrie Laing

David was born in 1859; his parents were John Tyrie and Isabella Fyffe Tyrie (born Carr) and had three siblings.

Very little is known about his early life and career except that at some time he was a member of the 91st (Argyllshire Highlanders) Regiment of Foot and the 93rd (Sutherland Highlanders) Regiment of Foot; they were merged in 1881 to become the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. The 91st became the 1st Battalion and the 93rd the 2nd Battalion.

The only other mention that I found of David Tyrie Laing was in a book by Peter van Wyk titled Burnham, King of Scouts in which he writes that Burnham met Tyrie-Laing at the Yukon during the Klondike gold rush in April 1898. How reliable this is I cannot say as there are no references and what I take to be loads of made-up conversation.

Tyrie Laing’s medals

Queen's South Africa 1899-1902, 4 clasps, Cape Colony, Orange Free State, Transvaal, South Africa 1901.

Presumably he was also awarded the British South Africa Company Medal with the inscription Rhodesia 1896.

David Tyrie Laing was killed in action 3 January 1901. He was mentioned by Field Marshall Lord Roberts in despatches, on 16 April 1901 who stated that he deeply deplored his death, and that he had shown himself "an officer of great merit and I am much indebted to him

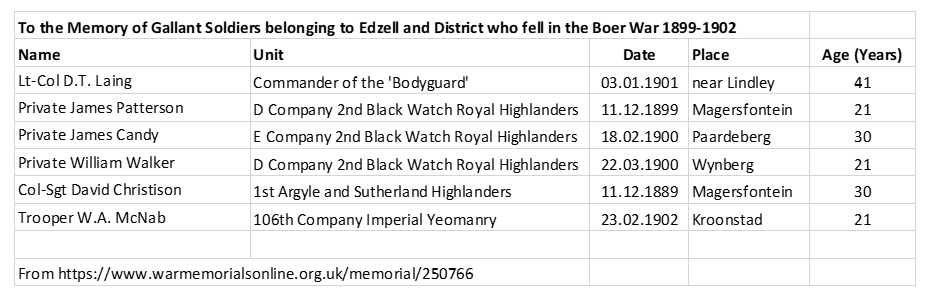

Edzell Boer War Memorial at the High Street, Edzell, Scotland

The memorial takes the form of a Celtic cross set on a tapering shaft, plinth and base and inscribed, “To the memory of gallant soldiers belonging to Edzell & District who fell in the Great Boer War 1899-1900-1901-1902. ‘Decorum est pro patria mori.'”

Sergeant Charles Hugh Halkett's account of the Inugu battle

Halkett was serving as a Sergeant in the Maxim Troop of the BFF in 1896 and wounded in the leg at Inugu. He went on to serve the Cape Mounted Rifles at Mafeking, the Cape Mounted Police, the District Mounted Police, the South African Mounted Rifles and the South African Police. I have corrected the original spelling mistakes.

“At 7 am on the morning of the 19th July 1896 we broke up laager about three miles outside the Matoppos Hills near a Fig Tree. At about 10 a.m. we reached Chawner’s Police Camp where we off saddled for 3/4 of an hour to give our horses and mules a roll and a drink. We then again saddled up and rode through very rough country into the heart of the mountains, our destination being Inugu Mountain. At about 1.30 pm we had a second off saddle for an hour for lunch. Having baked enough bread and cookies to last us five days previous to commencing this march we simply had to cook our kettles and were able to start our meals at once as our rations consisted of nothing but bread and Bully Beef and coffee. After being off saddled for ½ an hour I received orders to warn a section of my troop to accompany Lieut. Ferguson on a scouting expedition. I accompanied him with three men from my Troop—'The Maxim Troop'. We started off from the camp in skirmishing order but were soon compelled to march in single file, owing to the thickness of the bush and the roughness of the country. We proceeded in this fashion for about three miles and then came to a nice open patch and were once more able to proceed in skirmishing order. We proceeded about two miles further when we arrived at some huge rocks and on examining this spot more closely found that it had recently been vacated by the enemy as there were numerous fire places and plenty of grass had been strewn about which had evidently been used as bedding.

Whilst I was taking stock of this spot I was astonished on glancing to the left to see a large kraal with about 60 huts. We immediately turned our attention to this kraal. As there was no smoke issuing from any of the huts we at once came to the conclusion that it was deserted. Anyhow we took the precaution to march on to it in open order. It was truly a grand looking place at the foot of a very

pretty hill with natural caves dotted here and there and fine big trees. As we found our dusky brethren had decamped and had taken the precaution to close up all their doors very carefully we thought we'd alter things a bit for them and before you could say Jack Robinson we were flying around from hut to hut with fire brands and very soon reduced a bunch of once happy homes to ashes.

As we considered we would not do much good by proceeding any further we returned and very soon ran across our column on the march once more and can assure you we were all very pleased to see them again so soon and to join in our places. We had to go through several very nasty places and had to literally chop our way through in a couple of places. Thank goodness we were not hampered with heavy wagons and our mules were in the pink of condition otherwise we would never have reached our destination that night and would have been compelled to laager up in a terribly dangerous position. Between 5 and 6 pm we eventually reached Inugu Mountain and as our mules and horses were rather done up after their forced march through heavy country, it was decided that we should camp close under the Hill. We immediately formed laager cutting a considerable amount of bush etc. to protect ourselves from a rush. Posted our Picquets and Guards and were soon once more all gay and festive sitting around our camp fire discussing bully, cookies and coffee and the chances of an attack. As we hadn't had a brush with the natives for over a month, we were naturally getting a bit rusty and were beginning to give them up as a bad job and to think that we'd probably be another month before we had a slap at them.

Before retiring to roost we were all told off to our places in case of an attack and we slept in them that night and all fires were ordered to be put out, which order was promptly executed. About 9 pm we sent up a couple of rockets to inform Plumer's Column of our whereabouts but we failed to attract their attention. It was rather a nasty night and there was a good stiff wind blowing. I remember it well. I was lying next to young Harry Hillier, a young fellow who left Charter with me at the beginning of the Rebellion and who had been with me all along and who I now looked upon as my half section, as we had ridden and fought side by side for over three months. Poor fellow he had contracted a fearful cold whilst we were camped at Fig Tree. Before leaving Fig Tree camp I tried to persuade him to remain behind but he wouldn't hear of it. In the middle of the night I was awakened by him. He was coughing violently. I covered him up as well as I could and gave him an extra blanket which I found lying idle in our line. I then lay down and started gazing at the stars and wondered what the morrow would bring forth. The night had now become still and calm and the only sounds that could be heard were the footsteps of our Picquets who seemed to be more on the alert than usual and were visited about every half hour. An occasional challenge and No. 1 All’s well, etc.

At dawn on the morning of the 20th the whole laager was astir and our camp fires were gaily burning and it was pretty chilly and we were anxiously awaiting our morning cup of coffee. My troop were just in the act of dipping their pannikin’s into the camp kettle when we were startled by a single shot which was quickly followed by a volley. We dropped our pannikin’s like red hot spuds, the 'alarm' being immediately sounded and in about ten seconds every man was in his place. Owing to the arrangements of the Laager being so complete there was absolutely no confusion and we opened fire almost immediately. Our Picquets came rushing in at once and had a narrow squeak I assure you.

The Matabele evidently intended surprising us but their little plan was upset evidently by one of them tripping and causing his gun to go off. They started their attack on the rear flank of the laager and had their skirmishers extended on three sides of us. Sgt Money let them have it with his Hotchkiss [This was one of two 37mm Quick-Firing Hotchkiss guns on field carriages taken from the Portuguese at Macequece in 1891: The Ordnance and Machine Guns of the BSAC 1889-1896] as hard as he could peg and Capt. Hopper treated the attacking party in front with a shower or two of bullets from his Maxim and our line of skirmishers were firing steadily. By Jove, it was simply awful the row that was going on, what with the enemy chanting as they advanced, our horses snorting and the roar of musketry. For the first fifteen minutes we could see nothing but the flash of their rifles as they fired into us from their strong natural defences, ridges of rocks and bush. All we did was to watch for a flash and cover it immediately and patiently await the next one and then let rip. This seemed to encourage them for they ventured closer and closer and made one or two attempts to rush the laager but were driven back. As it got gradually lighter and lighter our firing increased and the nearer the brutes came, creeping along stealthily behind their natural fortress of solid rock and bush until within 15 yards of our position.

By this time they were plainly visible and we drove them back, scrambling away like a lot of baboons, turning round occasionally to fire from behind the rocks. Their leaders shouted out that they were getting the best of it and they again started on us with renewed vigour. We were getting quite interested in the fray by this time and were pegging away steadily. Capt. Laing was here, there and everywhere encouraging the men with quiet remarks such as 'Steady boys', 'Give it to them', 'Don't waste your ammunition'. My troop who were extended on the front flank for the express purpose of taking up the fire in case the Maxim jammed, were more like a lot of school boys than men fighting for their country; they were in the best of spirits, occasionally congratulating one another on a good shot. Harry Hillier had forgotten about his cold and was doing some excellent shooting. We had been keeping our eyes pretty well skinned for about an hour and a half when I received a tap on my right field boot. I immediately turned around and saw Lieut. Caldecott standing close to some Cape boys behind us. I asked him not to allow the Cape boys to chuck stones at us as one had just hit me on the boot. He simply laughed and said they were not throwing stones.

About 10 minutes after this I received a deuce of a crack in the left leg as I was lifting (bottom of page torn) air and caused me to kick myself in the back. I said to Hillier and Valentine who were lying on either side of me, 'By Jove, I believe I'm hit'. They immediately offered to carry me round to the ambulance wagon but I refused their aid and said I was all right; as soon as they resumed firing, I turned around and crawled away towards the wagons. On my way I came in contact with a small tree that had been knocked down by one of the wagons in forming the Laager the previous evening. I attempted to crawl over it but my great coat which I was wearing at the time prevented me from doing so. As my black brethren seemed to be paying particular attention to me and just then a cloud of dust was thrown up just in front of me which nearly blinded me, I came to the conclusion that I'd better chuck a dead one on it and perhaps they'd leave me alone. With this ruse I'm pleased to say I outwitted them and lay motionless until the firing ceased a bit and I then made a gallant scramble on hands and knees for the nearest wagon. I succeeded in getting to the wagon and then

feeling pretty secure I sat up against the wheel. Just then Capt. Laing passed me closely followed by the seven-pounder; as he passed me he asked what was up, I replied I'm winged. He said remain there and I will have you attended to in a few minutes. Capt Howe then came along and asked me what I was doing there. I replied those black devils have knocked me off my pins. I then asked him to pull my boots off. I then discovered that I was wounded in both legs and that I had wrongfully accused the Cape Boys of throwing stones at me, as it was a flesh wound I had received through the upper part of my right calf. Howe then left me and returned with a stretcher which was saturated with blood and I was placed on it and taken round to the ambulance wagon. Whilst I was sitting up

against the wagon I couldn't help admiring old Laing. He was bringing up the 7-Pounder into action and to bring the gun round smartly he manned the wheel himself, sighted the gun and then remarked 'Now then boys give them Hell'. Bang went the seven Pounder and he remarked 'Good shot'. Now then another shot a little lower down. Bang. I think that will settle them.

On my arrival at the ambulance enclosure I was awfully surprised to find several of my comrades stretched out all around. Two were actually dead and a third dying, being shot clean through the head. Bush and Bennett and Corporal Hall, Surgeon Captain Anderson and his men had a busy time of it bandaging with the bullets whistling past them and knocking chunks of bark off the trees close to them. Whilst Dr Anderson was bandaging my legs a bullet struck a tree close above his head and a chunk fell on to the stretcher I was lying on. He simply whistled and said that was a wee too close to be pleasant. Lieut. Ferguson amused me greatly when the bullets were coming in thick, he was calmly strolling about smoking a cigarette, firing an occasional shot as if he were shooting huts instead of natives.

In this fight, which was a fast and furious one, all ranks behaved splendidly except our supposed friendly allies who were huddled together amongst the horses and wagons like a lot of scared sheep and had to be threatened with death before they would come out. This fight lasted about five hours and we eventually drove the enemy off leaving 90 dead on the field. Our loss was three whites killed, ten wounded, 25 Natives killed, 28 wounded, 18 horses and mules killed, 8 wounded.

After we had succeeded in driving the enemy from their position and things had become a bit quieter, the ‘boot and saddle’ sounded and whilst we were in-spanning and saddling up a few straggling shots were fired at us and one bullet, I regret to state, found its billet by completely smashing Trooper Judge's ankle whilst he was in the act of saddling his horse. Our dead were placed in the ambulance wagon and the wounded were placed on the wagons and were made as comfortable as possible on top of the bundles of blankets. As these wagons were light spring wagons we did not feel the jolting much. When everything was in order we marched on towards the Chilili Valley. Shortly after starting we travelled through some old mealie lands and the jolting of the wagons did not improve the tempers of the wounded or their condition either. Our progress was naturally very slow and we occasionally halted to see what effect our seven-pounder would have in dispersing the natives who were massing on the surrounding hills, evidently with the intention of watching our movements. Two or three shots from the ‘By and By’, as the natives call it, sufficed to scatter them and we were then allowed to proceed unmolested. Finding that our so-called friendlies who were supposed to be our guides were not altogether to be trusted, a halt was made and our officers held a Council of War and ultimately decided not to go any further.

We then counter marched and after about an hours’ march found laager in a very strong position and our horses and mules had a few hours much needed rest. A temporary Hospital was immediately rigged up for the wounded who had had a very trying time of it lying on top of the wagons exposed to the sun. Any amount of grass was cut and a tarpaulin fixed up and we imagined ourselves on feather beds that night. A strong scherm of thorn bush was placed around us and we were well provided with luxuries from the Officers mess. It was truly a pitiful sight to see our unfortunate horses that had been wounded that morning marching along with the column with the blood running from their wounds until they dropped down utterly exhausted from loss of blood, one after the other never to rise again.

The night passed off fairly well and nothing of any importance occurred. Of course our picquets were doubled and were visited at short intervals as we expected a night attack. Next morning the mortal remains of Messrs. Bennet, Bush and Hall, who were killed on the previous morning were interred under a large tree. A short and impressive burial service was read over their grave and after the grave had been filled in; a large cairn of stones was erected over the grave, every man in the Column contributing his stone towards its erection to mark the last resting place of their late comrades. After breakfasting we resumed our march homeward and all of us were anxiously looking out for our late battlefield.

On arrival we found it literally strewn with dead horses, mules and natives. Many of the latter were evidently wounded the day before and had crawled out towards the stream of water which was close by and had died before reaching it. One Matabele who was wounded evidently did not think life worth living so hanged himself to a tree with a rope made of grass. Several of the dead had bowls of porridge alongside them but were probably too badly wounded to be removed and were left on the field to die. About a mile from this gruesome spot we halted for about an hour for lunch. Finding that a granary that was empty when we marched in to Inugu had been replenished by the Matabele commissariat, a foraging party was sent to collect the corn and grain. Whilst doing so one of the natives was wounded on the forehead, the bullet only grazing him. This shot was evidently fired by one of their wounded men. Several shots were fired at this foraging party but nevertheless they succeeded in bringing in all the grain without any further mishap. Having lunched we marched on to the Chawner’s Police Camp where we formed laager for the night.

Between eight and nine o'clock we were aroused by the sound of a bugle and the sounds of horses' hoofs. It was Captain Baden Powell with a relief force coming to our assistance, but as we required no assistance, after staying for about half an hour, they departed early next morning, whilst Dr Anderson was dressing my legs. I informed him that I thought the bullet was trying to work itself out at my heel as it was very painful and I could feel something hard there and there was a blue lump. He had a look at it, told me to turn over on to my stomach and before you could say knife he had run his knife around the supposed blister and out popped a villainous looking bullet. He remarked you had better keep this and have a brooch made out of it for your wife. Next morning about 9 am Dr Sutcliffe turned up with three ambulance wagons and a small escort. Laager was almost immediately broken up and we started on our march to Plumer's Camp, the wounded being placed in the ambulance wagons which were very comfortable but far too springy. About four pm we fetched up at Plumer's Camp and were immediately carried into the large marquee which was erected to serve as a hospital. It was almost full of wounded, both black and white men were in it and all received the same treatment.

I was awfully glad to see so many familiar faces in Plumer's Camp. I met any amount of old B.B.P. men whom I had served with in Macloutsie about an hour after our arrival in Plumer’s Hospital. Whilst I was having a bit of a doze, I was rudely awakened by four men carrying a stretcher. I wondered what was up. I was then gently placed on it and carted off to the (Butchers Shop) Surgery where chloroform was immediately administered to me and I remember just before I went off I remarked to the doctors that I was getting awfully drunk. It must have been about 10 pm when I awoke that night and found myself back again in bed with a Dr watching me as if I had stolen something. He asked me how I felt and as I replied damned hungry he went off and ordered me some dinner. I took some soup and then went off to sleep and awoke next morning feeling rather bad not having quite recovered from the effects of the chloroform and the butchering.

We remained in Plumer’s Hospital about five days, living on Kite paste and soup and were very glad when we were sent off to the Bulawayo Hospital. I was most fortunate in being put into a small ward with three of my own Troop and I assure you we had a jolly good time of it. The Mother and sisters were very kind and attentive to us and treated us very well indeed. In fact we could not have been better cared for even in the bosom of our own families. It was a case of nothing but operation after operation with me and I had the pleasure of going under chloroform no less than five times and my left leg is now one mass of incisions but I'm pleased to say that after about two months in Bulawayo Hospital and three months on crutches I was able to dispense with the service of my spare legs and found that I got on very well with a stout stick and could walk very comfortably. The wound I received in my left leg was evidently caused by a Snider Bullet. It entered at the inside of the calf and fractured the skin in two places. It then travelled downwards and was eventually extracted on the outside of the heel just below the ankle. "As a memento I now have in my possession the flattened Bullet and about 18 small splinters of bone which have been removed and have worked themselves out at the various operation incisions during the last two years. Thanks to the careful nursing and untiring attention I received from the Nurses and Doctors whilst in Bulawayo Hospital I am once more fairly strong on my legs and am able to play cricket and tennis once more, but alas I have had to give up Rugby for ever."

References

R.S.S. Baden-Powell. The Matabele Campaign 1896. Methuen and Co, London 1901

I.J. Cross. The Ordnance and Machine Guns of the British South Africa Company 1889-1896. Military History Journal Vol 16 No 2 – December 2013

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890-1897. Rhodesiana Publication No. 12, September 1965

C.H. Halkett with introduction by M. Gelfand. With Laing in the Matopos: A Medical Casualty in the Inungu Battle. Rhodesiana Publication No 24, July 1971 (NAZ Ref HA-14/1)

H.A.B. Simons. Correspondence; With Laing in the Matopos. From Rhodesiana Publication No 26 July 1972

J. Lourens and S.A. Watt. Fredericksdale 3 January 1901, A little known engagement of the Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902. Military History Journal Vol 14 No 3 - June 2008

H. Plumer. An Irregular Corps in Matabeleland. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co Ltd, London 1897

F. Sykes. With Plumer in Matabeleland. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1972

D. Tyrie Laing. The Matabele Rebellion 1896 with the Belingwe Field Force. Dean & Son Ltd, London, 1897

P. van Wyk. Burnham, King of Scouts. Trafford Publishing 2003

Notes

[i] An Irregular Corps, P143

[ii] Selected by Baden-Powell on 22 July 1896

[iii] A Maxim weighed 54lbs (24kgs); the tripod 60lbs (27kgs) and ammunition boxes weighed 15lbs (7kgs) each. The gun-saddle weighed 86lbs (39kgs) and the ammunition saddle 50lbs (23kgs)

[iv] An Irregular Corps, P150

[v] Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890 – 1897

[vi] Ibid P279, although Tyrie Laing only lists 20 friendlies

[vii] Frank Sykes also lists a Maxim as well as the Hotchkiss

[viii] The Matabele Campaign, 1896, P120

[ix] Sykes says they “advanced for about a mile up a narrow gorge.” Possibly he means this is from Laing’s first laager and not from Chawner’s Camp which is much further

[x] The Matabele Rebellion 1896, P282

[xi] Barricade of thorn bushes

[xii] The Matabele Rebellion 1896, P283

[xiii] Ibid, P285

[xiv] Ibid, P296

[xv] Both Tyrie Laing and Sgt Halkett mention 90 amaNdebele dead, but this appears more guesstimate

[xvi] The Matabele Campaign, 1896, P162-3

[xvii] Ibid, P296

[xviii] Earlier in the paragraph Sykes refers to two Maxims only. Plumer states Nicholson’s force had one 2.5inch gun, one Hotchkiss and two Maxims so there is some confusion

[xix] Ibid, P182

[xx] The Matabele Rebellion, P318

[xxi] Google Earth does not have Plesier as a location

[xxii] Fredericksdale is also not listed by Google Earth

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: