Home >

Matabeleland South >

Bushtick Mine, now the location for Falcon College, the independent boarding school in Matabeleland

Bushtick Mine, now the location for Falcon College, the independent boarding school in Matabeleland

Bushtick Mine, now the location for Falcon College, the independent boarding school in Matabeleland

Background

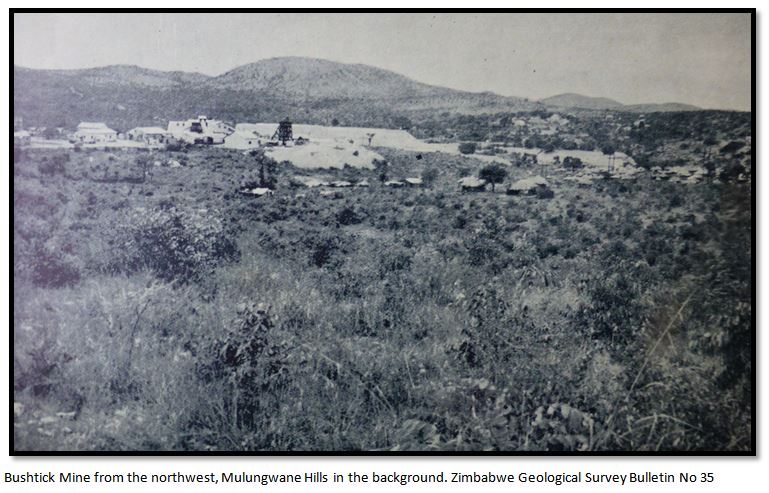

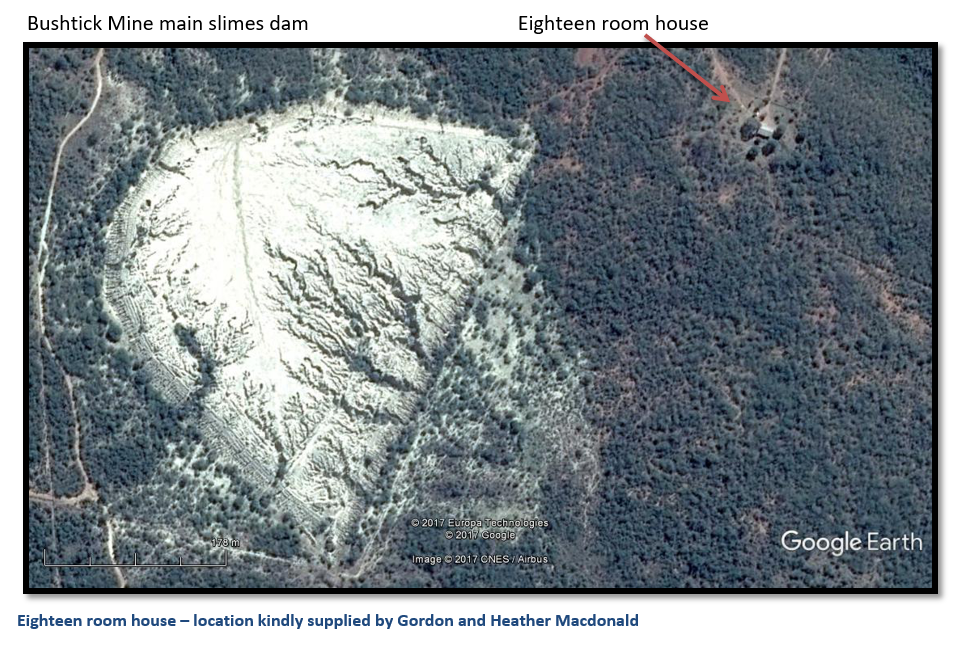

Bushtick is a dormant gold mine situated 8 kilometres NNE of Esigodini in the Esigodini Greenstone belt, within the grounds of Falcon College. Over its lifetime the mine was a major gold producer as evidenced by the large tailings dump visible in the photograph below:

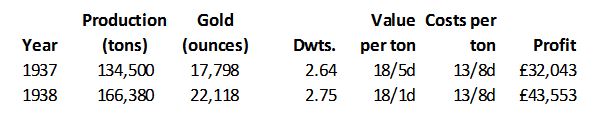

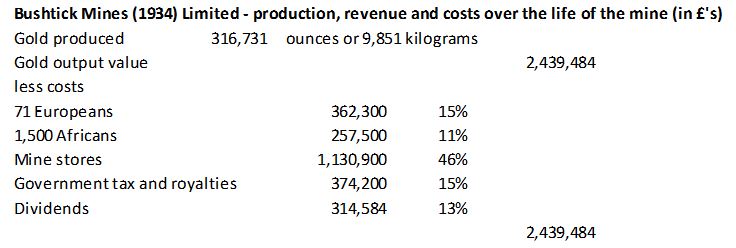

Despite the higher gold output during the period the reefs were mined by Bushtick Mines (1934) this eighteen year period was characterised by low yields and the return on capital to shareholders was a very modest 4% over the period.

Pre-European mining

Roger Summers in Ancient Mining in Rhodesia lists the output at the Bushtick mine site as lower than many of the other pre-European or “ancient” gold mining sites in the surrounding area based on the size of the open stopes and gold values. The Alice, Intabanenda, Red and White Rose all had estimated outputs of between 10,000 – 50,000 ounces (300 – 1,500 kilograms) with Bushtick’s output was estimated at 1,000 – 5,000 ounces (30 – 150 kilograms)

Early European history

A portion of the reef was pegged on 27 April 1895 by Charles Trevor with the line of strike indicated by “ancient workings” and the open stopes along the quartz outcrop are described as not large and about 4.5 metres deep.

In 1906 Thomas Meikle acquired a 50% interest and worked the claims through Captain J.A. Warwick, who pegged additional claims. Production started on 1 May 1906 from open cast workings on the outcrop with the ore being transported 4.5 kilometres to the Red and White Rose mine which had a twenty stamp mill. This milling arrangement continued until July 1907 when the mill was moved to the Bushtick claims.

By this time the Hollins section had been developed to the second level at 150 feet. All ore above 50 feet had been mined out with the reef averaging between 12 and 15 feet, but in places narrowing to 4 feet. In isolated spots the grades were good; one section of 71 inches gave 9.8 pennyweights per ton, abbreviated to dwt. (15.2 g)

The Bushman Mining Syndicate held 427 claims covering 1880 acres which were eventually taken over by Bushtick Mines (1934) Limited. The members of the syndicate were: H.C. Hardy, R. Sterkey, T. Speight and J. Ralstein. It appears from an article that Mark Sturgeon found called “Memories of Bushtick” that the eighteen-room or ‘the big house’ existed at this time as the manager’s residence, but for some time was used as a married and single quarters for employees.

The Warwick East section was mined as a large open cut, as the pay ore extended wider here than elsewhere; at 55 feet a crosscut was dug to expose the full width of the seam, which averaged 5.3 dwt (8.2 g) over 62 feet with the central 20 feet assaying nearly 10 dwt (15.6 g)

An estimate of the ore reserves in 1907 gave 74,000 tons averaging 5.6 dwt (8.7 g) A.H. Ackermann, the resident mining engineer for the British South Africa Company viewed the prospects of the Bushtick Mine with enthusiasm and predicted it would develop into one of the largest mines in southern Africa.

Formation of Bushtick Mines Limited

Bowen’s Gold Mines of Rhodesia 1890 – 1980 starts in 1908 with the registration of Bushtick Mine Ltd whose initial Directors and officials were the following:

R.R. Hollins (Chairman)

G.W. Hollins

T. Meikle

Captain J.R. Warwick

Digby V. Burnett (Mine Manager)

F. Engright (Mine Captain)

F. Silbermann (Engineer)

F.S. Cochrane (Reduction Officer)

J.C. Stoker (Surveyor)

B.J. Deacon (Compound Manager)

Dr. J.R. Forsyth (Mine Doctor)

The flotation of Bushtick Mines led to a secret investigation by the Mining Commissioner in Bulawayo and an unpublished report to the Secretary of Mines. Messrs Meikle and Warwick held the mining claims and floated the company with a nominal capital of £75,000, of which £60,000 was subscribed. Sir George Farrar, a Rand financier bought one-third of the subscribed capital anonymously avoiding any taxes on the transfer of claims and plant.

Shortly after the flotation, a closed meeting of Directors had re-allocated the company’s assets with the 200 blocks of mining claims being valued at just £10,000, or £50 each, and the balance of £50,000 in the plant, buildings and “a few donkeys.”

The facts were that Thomas Meikle and Captain Warwick purchased the plant and buildings of the Red and White Rose Mine for £20,000 and transferred them to Bushtick Mine just 4.5 kilometres away, plus additional plant for £5,000; meaning the mining claims valuation was a more realistic £35,000, or £175 per claim.

This tactic avoided a higher rate of taxation that would have been payable to the British South Africa (BSA) Company; but because nothing could be proved, the report was quietly filed away.

British South Africa Company 1013 one penny stamp franked at the Bushtick Mine Store and Postal Agency a few hundred metres west of the mill.

In 1909 R.R. Hollins bought out Farrar’s interest and also that of Thomas Meikle, but not Captain Warwick’s one third share.

Ongoing royalty dispute

Bushtick Mine initially had no slimes plant to process the treated sands and was recovering only 60 – 70% of the gold in their sands circuit and Mr A.H. Ackerman was asked for a reduction in the royalty payable to the BSA Company. In reply, he pointed out that many operating gold mines in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) did not have did not have a separate slimes plant and it was up to the management of the mine to design their gold process circuits to recover as much gold as possible; in any case Bushtick Mines were paying a lower 3.5% royalty as their gold recovery did not exceed 22 shillings per ton.

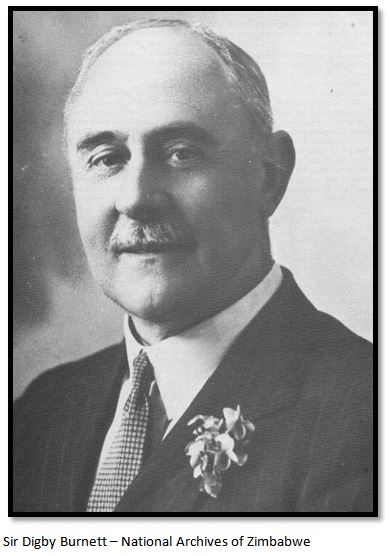

Arrival of Digby V. Burnett as mine manager

Burnett’s arrival in 1912 led to a solution in the ongoing disputes with the mining department and his cost reduction programme turned an annual £14,400 loss into a £8,400 profit. The Mining Commissioner commented: “This fine performance at Bushtick, where operating costs have dropped to 13 shillings a ton, due to his rearrangement of machinery, including the largest tube mills in the country, says a lot for him.”

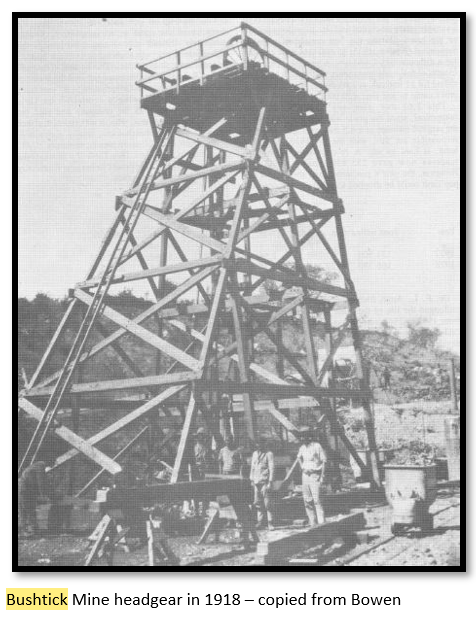

Burnett greatly expanded the plant capacity so that 12,000 tons a month of ore could be milled utilizing:

20 x 1,250lb stamps

8 Nissen stamps

3 x 16ft x 5ft Krupp tube mills

Each stamp mill managed to mill over 9 tons of ore per day using 0.6cm x 1.3cm outlet screens before this coarse feed went to the tube mills

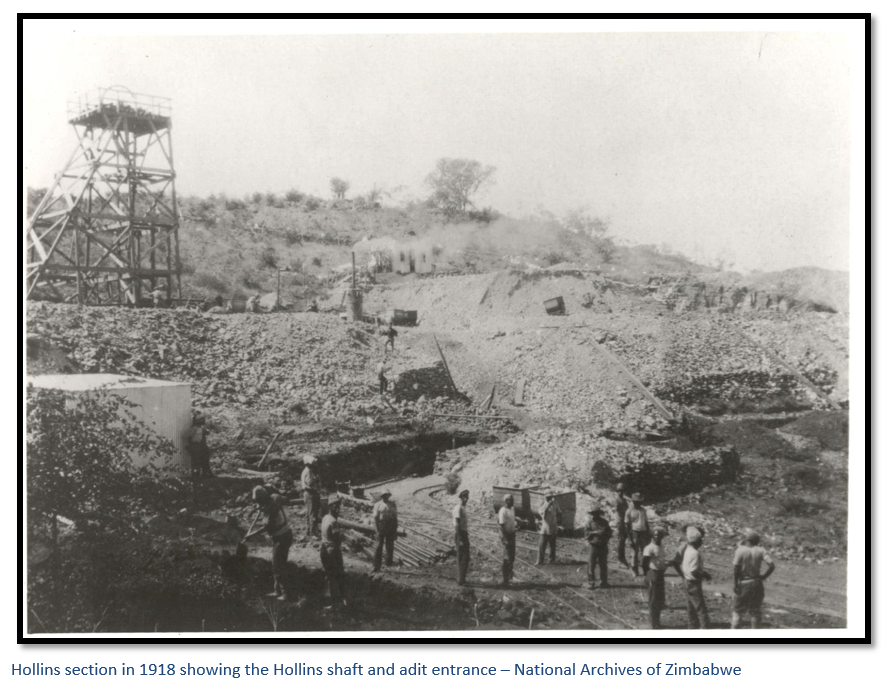

Two three-compartment shafts were dug at the Hollins and Warwick sections and a slimes plant using the Adair-Usher process was commissioned to increase the gold extraction to 90%, most of the plant being purchased piece-meal and second-hand.

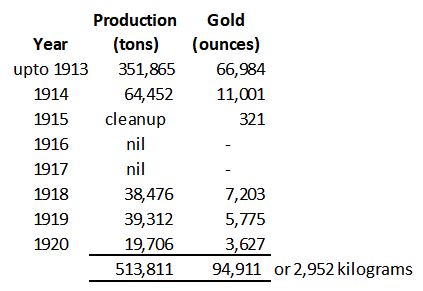

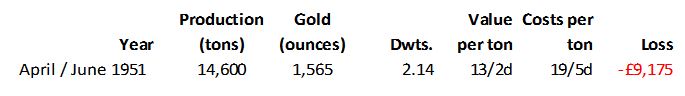

However, despite Burnett’s efforts, World War I adversely affected the mine’s operations as seen on the table below and at the end of 1920 operations at the Bushtick mine were wound up.

The average gold recovery was 3.7 dwts per ton (5.8 g) and the total gold output of 2,952 kilograms had a value of £408,754 equal to 15 shillings 10 pence per ton milled.

Burnett also drew up a plan for a six kilometre aerial cableway from the Bushtick rail siding to the mine to carry the monthly 900 tons of coal and other supplies.

However by 1920 the mine was in liquidation and the property passed into the ownership of the Standard Bank. Basically the failure was due to the high cost of power and a reduction plant which could not cope with the large tonnages. In 1920 working costs averaged 26/9d per ton, of which the mill accounted for 12/0d and with only an 80% recovery, equal to 3.7 dwt, the mine made a loss of £8,672 in that year.

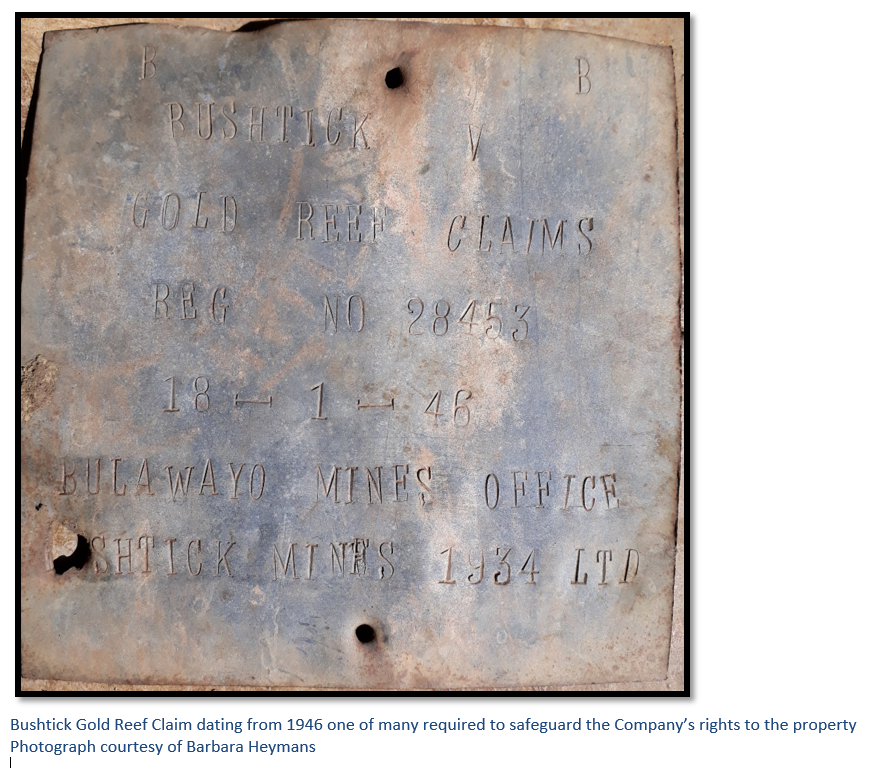

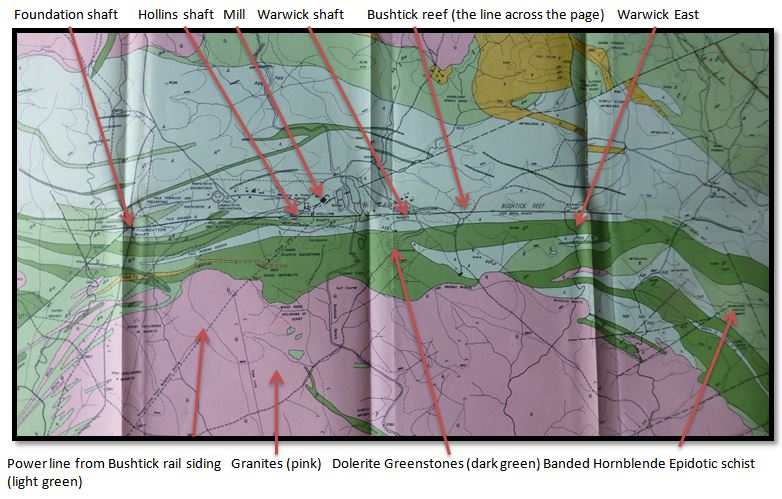

In the claims plan above, taken from the 1939 financial accounts, the Eveline and Woolwinder claims are coloured red, Bushtick claims are registered along the strike of the reef with one single Willoughby’s Consolidated claim near the Warwick shaft.

Years 1921 - 1933

Following the winding up of the mine in 1920, small scale operations were carried out by Rhodesia Gold Fields Ltd who were prepared to dewater the Warwick section for a purchase price of £80,000; £50,000 to be paid in cash and the balance in shares. But when Mr F.P. Mennell could find no new ore reserves the option was abandoned and then small gold outputs were made by E. St. J. Drysdale, but never amounted to much.

The gold premium came into operation from October 1931 and revived interest in the Bushtick Mine. A ten stamp mill was erected by a local syndicate and the results paved the way the successful flotation in London of Bushtick Mines (1934) Limited.

Bushtick Mines (1934) Limited

The company was formed on 15 January 1934 with a nominal share capital of £500,000 in ten shilling shares of which £450,000 was issued. By 1936, the Chairman Mr H.U. Moffat stated that expenditure of £463,806 had been incurred on the installation of the gold process plant, working expenditure and acquisition of 427 gold claims from the Bushman Mining Syndicate.

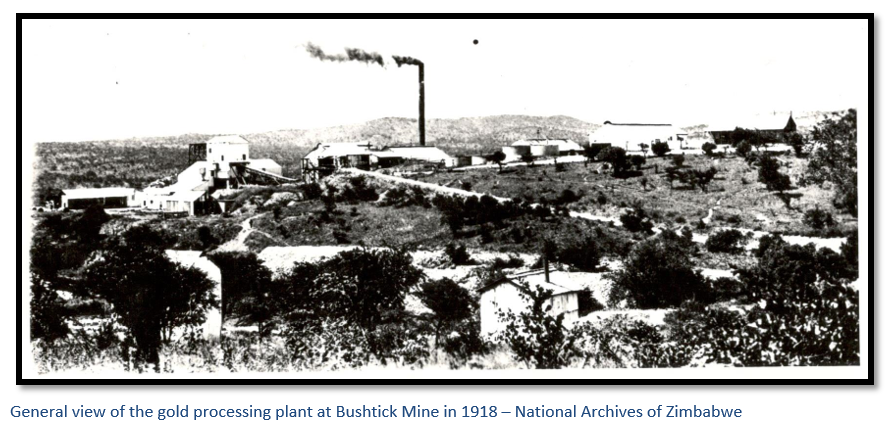

The Plant

Burnett’s plan for an aerial cableway was dropped; instead the main power plant consisting of three Babcock and Wilcox boilers driving two 1,250 kW Metropolitan Vickers Turbo Alternators, was sited at Bushtick rail siding with a six kilometre power line to the mine; this was completed in nine months and began operating in December 1934.

Production quickly rose to 15,000 tons of ore processed per month. A Hadfield jaw-crusher followed by Symons cone crushes reduced the ore to 1.27cm which was fed into two 6 x 20ft tube mills and one 7ft x 8ft ball mill. The resultant slurry was fed over corduroy tables to extract the coarse gold and then into 2 x 12ft diameter x 36ft high Brown tanks with rotary filter and finally precipitated in a Crewe Merrill Plant.

The foundations of the mill can still be seen below the laundry. Ore hoisted up the Warwick shaft was brought across by lorry to be broken up and milled, as was up to 2,000 tons of ore a month from the Eveline and Woolwinder mines on the western edge of the claims.

Water was pumped from the shafts and supplemented with supplies from the Ncema River when necessary with the wastes being pumped through a pipeline onto the slimes dumps.

Development

Development of the underground drives proceeded at a rapid pace with 92 metres being accomplished in 26 shifts on three level drive to connect the Hollins and Warwick sections in May 1935. In 1936, despite a severe subsidence problem in the Hollins section over 900 metres of development was achieved and additionally, a 120 metre drainage adit was put in at the Hollins section which enabled the workings to be cleared of water to the eighth level. By 1937 the Hollins shaft was 260 metres (854 feet) and the Warwick shaft was at 270 metres (889 feet) and both would eventually be re-enforced with concrete and reach 292 metres (960 feet) deep. Both shafts were connected under the Bushtick River on the third and eighth levels and this proved very useful as the Warwick shaft became weakened with water ingress and the hoisting speed had to be reduced, so the balance of ore was taken in hand-pushed ore bogeys along the 18 inch railway which served the entire underground network of tunnels through to the Hollins shaft and hoisted from there.

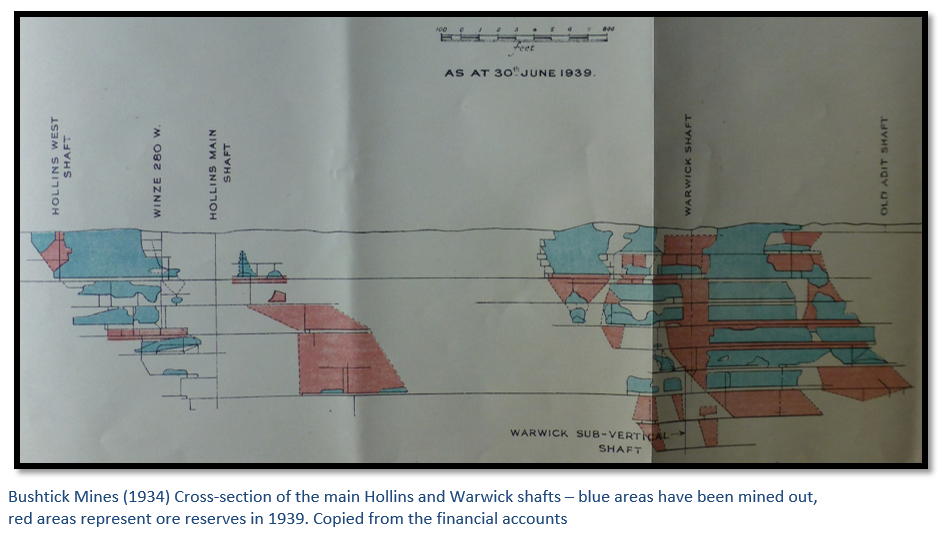

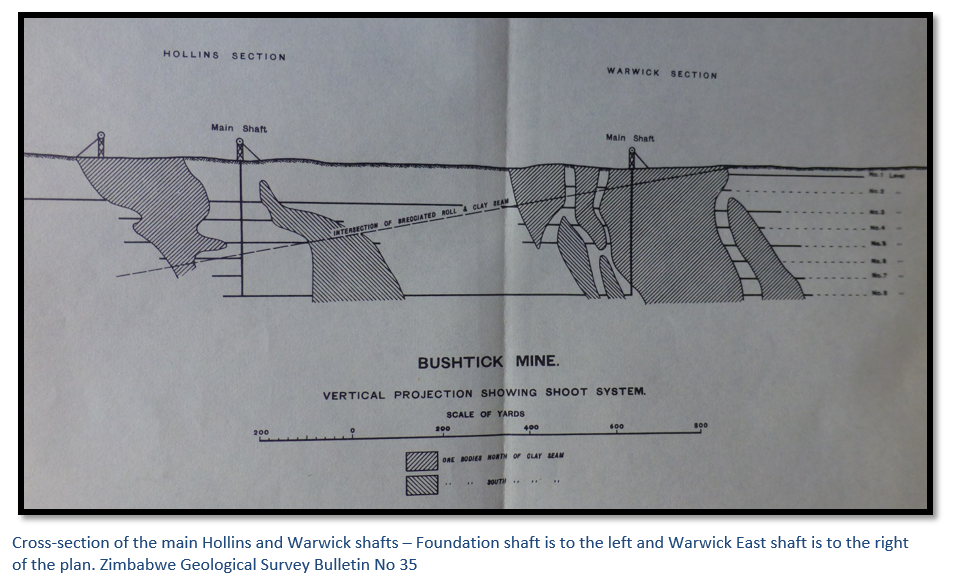

Ore Reserves

The claims totalled 12 kilometres in length; the initial targets were the known reefs worked by the previous company until 1920, and extensive exploration was carried out along the strike. The Hollins, Warwick and Warwick East sections were the main centres of activity, although the Foundation and N’cema reefs were added; the N’cema reef being outside the original claims.

The ore body is an impregnation along a fault zone which runs parallel to and at a small distance from the northern edge of the Essexvale granites. All the ore shoots lie at the same distance from the contact, while the two main shoots, Hollins and Warwick, are directly opposite bulges of schist which project out into the granite.

The Bushtick reef runs east south east at 120° and dips north-north-east at an average angle of 83° with the dip and strike being maintained throughout the mine with unusual regularity. Greenstones of intermediate and basic composition are the predominant rock types along the strike and in the workings.

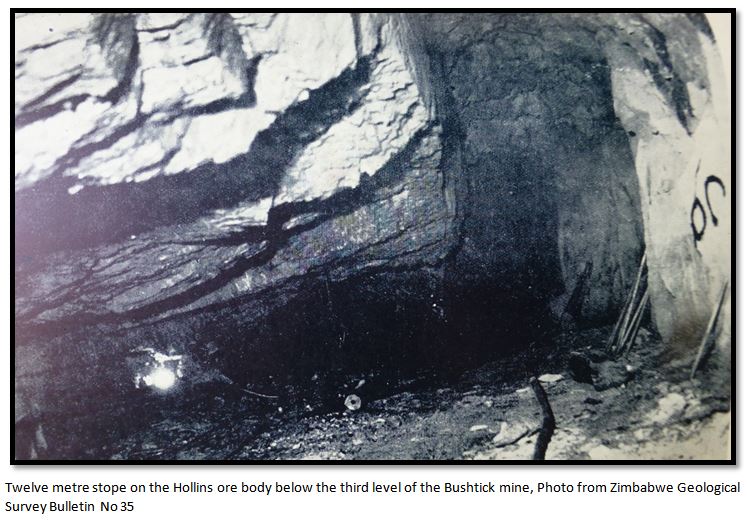

The ore shoot has a maximum quartz body width of 46 feet (14 metres) but this only extends for a short distance along the strike and loses its values below the third level and all high-grade ore has been stoped out from the surface down to this point.

The Warwick section has been the most consistent and largest ore-producer on the property. Six separate lodes have been worked, but the low-grade areas in-between are not always well-defined and visible gold was extremely rare on the Bushtick reefs.

An initial 1935 survey revealed the ore bodies to be wider than the earlier records indicated and as a 90% gold recovery was expected, prospects looked good. However, values throughout were found to be uneven, but in the Hollins section, higher gold values were usually found in the sections of ore body nearest to the clay seam. It has been assumed that the mineralizing solutions containing gold ascended up through the clay seam and replaced the rock walls.

The best gold values were found in the Warwick section; the shoot on the 11 level on the east drive revealed 90 metres of 21 metres wide reef at 4.8 dwt (7.5 g) but at 15 level the reef had reduced to 73 metres of 15 metres wide reef at 3.5 dwt (5.4 g)

The original calculations estimated that production of 10,000 tons a month were optimal for return on capital and prolonging the life of the mine; however the lower than anticipated recovery in 1935 of 2.63 dwt (4.1 g) meant a reappraisal of the ore reserves to 285.589 tons at 3.5 dwt (5.4 g)

The writer of ‘Memories of Bushtick’ calls Dr Amm “a genius” for finding the Warwick East extension at Bushtick mine. Much share speculation took place in anticipation of the results and Rowland Sterkey suspected the assayer, Cook Jansen, of being the source of the leak. Jansen in reply suggested that Sterkey put the charges in writing so that he could sue for defamation and that he was resigning. When Sterkey replied that Jansen was holding a gun to his head, the man replied: “I wish I were Mr Sterkey, I’d pull the trigger.” Needless to say in time the tempers cooled down.

The deposit which strikes 120°, dips 80° north is formed by the silicification, carbonatisation and brecciation of mafic volcanics along a wide shear zone near the edge of the Essexvale Greenstones which can be seen clearly going across the page above.

In 1944 in a final attempt to locate further ore reserves, boreholes were sunk from both the Hollins and Warwick shafts to a depth of 823 metres (2,700 feet) but without any additional reserves being found.

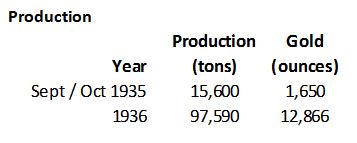

Early results proved disappointing; the actual recovery was 2.63 dwt (4.1 g) and the 1935 working profit was just over £20,000. This proved much lower than the original anticipated recovery of 4.6 dwt (7.2 g) but did show that mining could still break-even at 2.5 dwt (3.9 g) rather than the 3.0 dwt (4.7 g) in the original plan.

Production was stepped up to 15,000 tons with the expectations of a £70,000 annual profit, but this was never achieved.

The lower gold grades changed the nature of the mine as an investment; now a high crushing rate was required to keep it at break-even and in 1938 the new Mine Manager, E.L. Gay Roberts asked the Government for a reduction in the royalty rate as the shareholders had received just £56,250 in dividends over the past four years, a return of just 3.0%.

This was turned down, and despite Dr F.L. Amm extending the Hollins east reserves after 12,000 feet of extensive development drilling, from 1944 both the tonnage milled and grades kept dropping.

At this time over 300 staff was still employed, but the situation could not continue and by the end of the year the mine was on a care and maintenance basis with all equipment withdrawn from underground.

All attempts to sell the mining claims and mine housing proved fruitless and a final pay out of cash was made to shareholders of £115,000; approximately 2/6d on each 10/- share.

Bushtick Mine never turned out to be the financial bonanza that its shareholders hoped for, but it made a significant contribution to the local economy.

Over its eighteen year life, the £314,584 of dividends returned to shareholders represented only a 4% return over the eighteen years of the life of Bushtick Mines (1934) Limited. This modest annual return was less than the shareholder’s initial investment, despite the Bushtick mine being briefly the largest goldmine in the country, and illustrates the very speculative nature of mining.

Bushtick Mine as a community centre

At its peak, the mine employed 1,820 employees and because of its isolated site, sports and recreational activities needed to be provided. There were beerhalls and sports facilities; football matches and film shows were organised and competitions held which people from the surrounding countryside attended; at one time there were nineteen small workings within a distance of eight kilometres.

The author of ‘memories of Bushtick’ says the mine club, now the assembly hall, was opened by Howard Unwin Moffat, son of John Smith Moffat who knew Lobengula and grandson of Robert Moffat who knew Mzilikazi, with a gold key cast on the mine from Bushtick gold.

The same writer says that the Rev. Maurice Lancaster arrived at Bushtick unannounced one Saturday on a bicycle from Bushtick siding. His first service had a congregation of one person and as he was introduced to everyone at Sunday afternoon tennis by the mine manager as ‘Reverend Birmingham’ the name stuck, but his congregations improved. On Saturday evenings those in the bar could be heard practising “fight the good fight” (not always sung) and “abide with me” by an enthusiastic, if not always that sober, congregation.

The Bushtick golf course was the first to have grassed greens in Matabeleland and the above writer witnessed one practice shot nearly decapitate the mine manager’s daughters’ dog. A wayward drive hit a caddy in the forehead; who promptly collapsed. The player rushed up to him expecting a charge of manslaughter; but the caddy got to his feet saying “sorry boss!”

Falcon College rises like a Phoenix

All the mine buildings and infrastructure were handed over to the Trustees of Falcon College and the school opened its gates in 1954. Homes that had housed miners and their families would now house teaching staff and boarding school boys, mine offices would become administration offices and classrooms, other mine facilities such as the tennis courts and the swimming pool would also become school facilities. Today the school has a thriving community of teachers, supporting staff and schoolboys and has a proud academic and sporting record. [See the website: www.falconcollege.com]

Sir Digby Burnett

Digby Burnett was born in 1875 at Caputh, Scotland, and was educated at Marlborough, Wiltshire. After training as a mining engineer, he came to South Africa in 1892 and worked for the influential mining company of H. Eckstein and Company with whom Abe Bailey was associated. It was during

this time that Abe Bailey came to know him and assess his worth, later the two men were to collaborate for the best part of thirty years and Digby Burnett’s life and career were to a very large extent shaped by Abe Bailey who became Chairman of Lonrho.

Digby Burnett worked on a number of Rand mines, including the City and Suburban, Durban Roodeport Reef Limited, the New Heriot and Jumper's Deep and Crown Reef Mines and was eventually drawn into the political intrigues that were going on at the Rand between the uitlanders and the Transvaal Republic and was no doubt inspired by Abe Bailey who served on the Reform Committee. He was one of those who joined the botched Jameson raid between 29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896 as they approached Johannesburg, before being defeated by the Boers at Doornkop. Digby was captured by the Boers, but managed to escape, and thus missed being charged for high treason.

During the Anglo-Boer War he served with the Railway Pioneer Corps and was also a correspondent for the London Times. He left the Rand in 1906 to work on the West Coast of Africa, considered then to be the white man's grave. After three years, he returned to South Africa to take up an appointment as General Manager of the Pigg's Peak Development Company Limited that owned a mine in Swaziland.

He first came to Rhodesia in 1912 to manage the Bushtick Mine and to act as consulting engineer to its Chairman, Mr. R. R. Hollis and after four years he moved to Salisbury as loco superintendent for the Railways. Soon afterwards, Sir Abe Bailey asked him to become his agent and consulting engineer for his group of companies in Rhodesia.

From 1921 to 1951 he was General Manager of the London and Rhodesia Mining and Land Company Limited (Lonrho) and dominated the company and its subsidiaries for which he was responsible for the 30 years he was associated with the company. It was largely due to his engineering skill and Sir Abe's faith that the Cam and Motor Mine, where the ores were refractory and difficult to treat, was developed on a large scale and turned into the largest gold mine in Rhodesia and into one of the largest in the world. He was a Director of Cam and Motor, the Sherwood Starr Gold Mining Company Limited near Que Que (now KweKwe) and the Rezende Mine at Penhalonga.

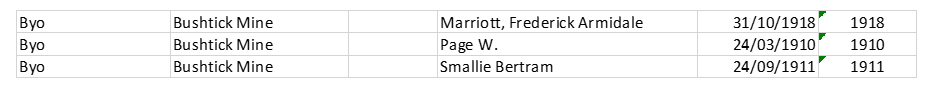

Bushtick Cemetery

The cemetery is located 0.5 kilometres south of the Bushtick reef approximately midway between the Warwick shaft on the east of the Bushtick stream and the open cut at Warwick East.

There is no trace of any grave for W. Page, the earliest burial, who died in 1910.

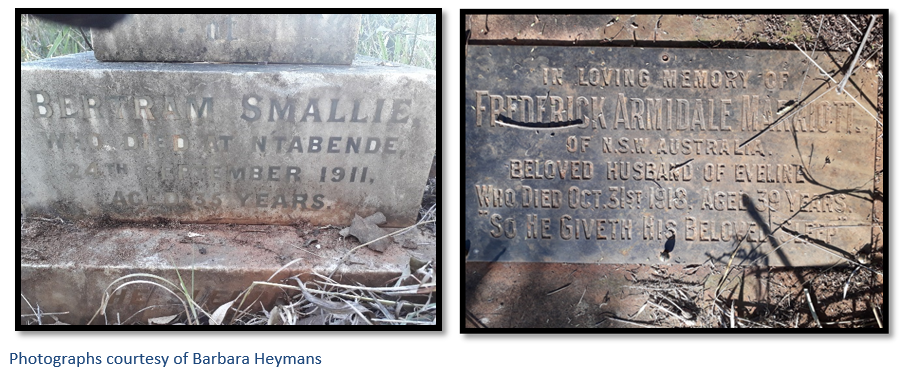

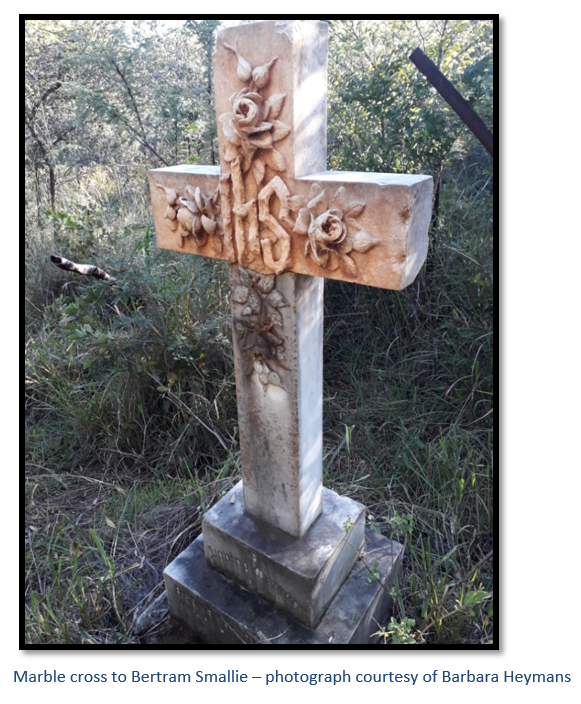

Bertram Smallie’s epitaph states he died at Ntabende on 24 Sept 1911 aged 35 years

He was married to Hilda and they had at least one son, Dan Norman born in 1911, who went to Plumtree School, joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve and was killed in a flying accident on 28 March 1943; clearly they were long-term residents of Matabeleland.

The epitaph for Frederick Armidale Marriott of NSW Australia states he was the husband of Eveline and died on 31 October 1918 aged 39 years. “So he giveth his beloved sleep.” The death records state that Fred Marriott was from England, he married Eveline Lakeland from Australia and they had three children.

The fact that their epitaphs say they both died indicates they were not killed in mining accidents; rather illness or other natural causes.

For many generations of Falcon College schoolboys (I can say this with confidence as we now know the names in the cemetery) there has been a myth that a miner named Charley stalked the corridors of the dorm houses on dark nights!

I personally can recall perpetuating this myth by wearing a sock on one foot and a cadet boot on the other and walking slowly in the dark along the wooden shoe locker outside the dormitory of the Hervey House first-year boys. The slow thump of one foot on the wood top was guaranteed to terrify the bravest of first years...from their dormitory gasps of horror; from the other giggles because they had heard it the year before!

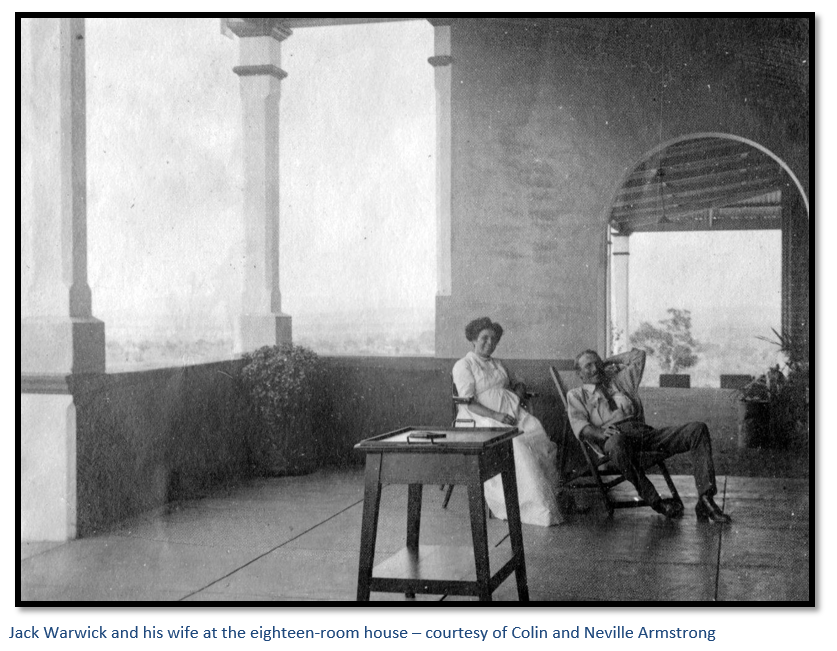

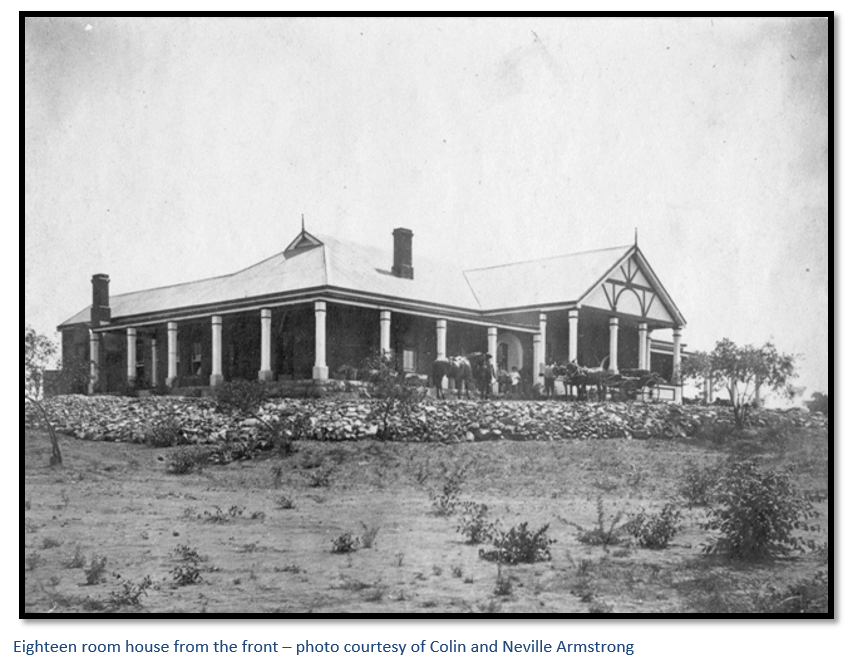

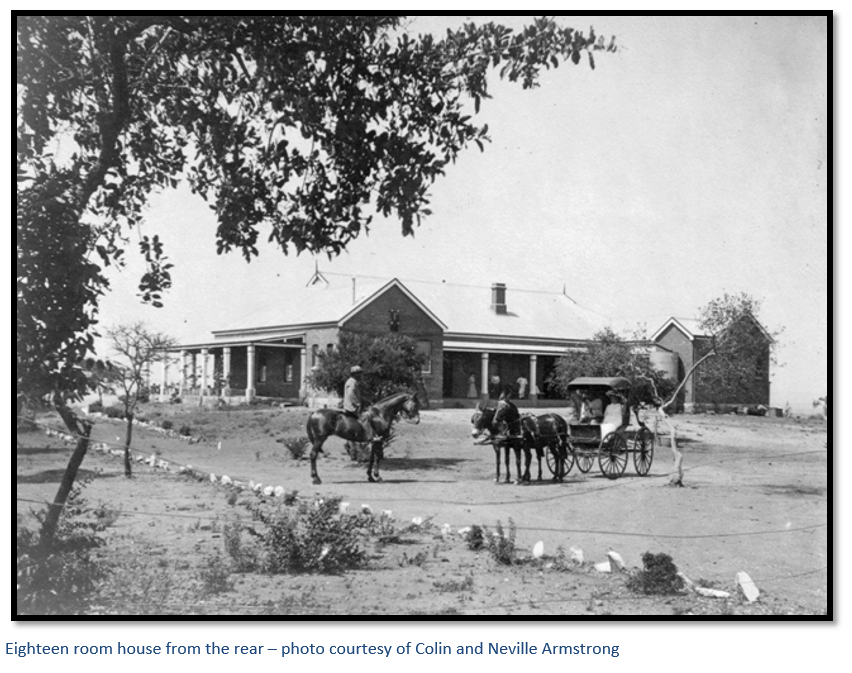

Eighteen room house

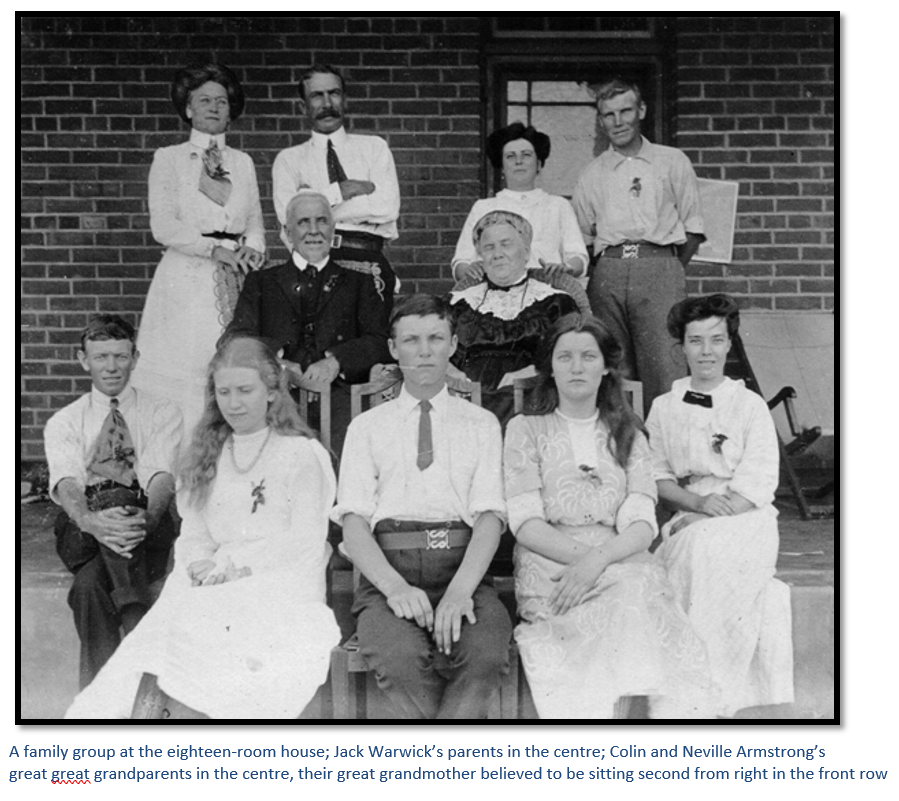

This building was probably constructed by Capt. J.A. “Jack” Warwick, the great grandfather of Colin and Neville Armstrong, as the mine manager’s house. The Warwick shaft and Warwick East open cut were named after Jack Warwick and in these glory days of the Bushtick Mine its future prospects were viewed with great enthusiasm and were reflected in the scale and grandeur of the eighteen room house.

Later during the tenure of the Bushman Mining Syndicate, the eighteen room house was used as married quarters for the various staff. In ‘Memories of Bushtick’ by one who lived there is told the story of an Irishmen who customarily drank until he was senseless. One night his wife sewed him up in his blankets and having achieved a strait-jacket effect, thrashed him unmercifully with a sjambok until he promised never to drink again. The writer wasn’t sure if the Irishman kept his word, because next day they both left the mine!

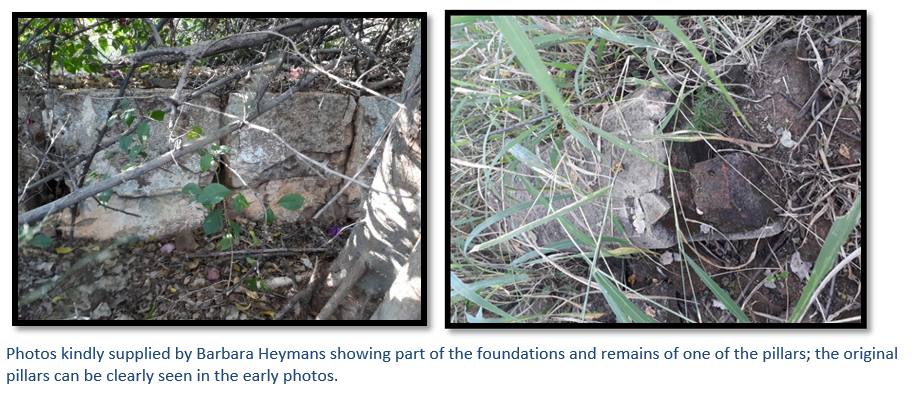

The eighteen-room house where Jack Warwick and his family lived, then Sir Digby Burnett, later President of the Chamber of Mines entertained friends and guests, now lies lost and neglected. Its bricks were moved in the 1950’s by the schoolboys to make brick pavements, today only the former grand stairway leads up to the foundations.

The GPS co-ordinates for the eighteen room house are 20° 13′ 10.45″ S and 28° 58′ 39.35″ E.

Falcon Old Boy’s experiences

Richard Wolfe-Daimpré adds that his grandfather Fred Wolhuter worked on the mine in the 1930's to 1940’s as an underground shift boss and because his work as a gold miner was considered vital for the war effort he was not allowed to volunteer to serve in the military forces.

Charles Summers’ father qualified as an electrical engineer in Britain and was sent to Rhodesia after World War II to help build the Bulawayo power station, but was initially based at the power station operating at Bushtick siding which was supplying electricity to Bushtick mine and to Bulawayo.

The family of Paul Seftel has an historic connection with Bushtick Mine; here is what he wrote:

In the 1930s my great-uncle James Krikler and his business partner John Ralstein were part-owners of the mine. Their business, Ralstein Brothers & Krikler, was mostly involved in retailing, hotels and ranching in and around mining towns, especially Shabani and Filabusi, but as the following extract from my great-uncle's (unpublished) memoirs show that from time to time they invested directly in mines themselves. Words in brackets are Paul’s explanatory notes:

John thought the Bushtick Mine, not far from the Mayfair Mine, worth looking at. The Bushtick, once worked by Tom Meikle and afterwards by a mining company, was at one time the biggest mine in the area and had produced a lot of gold. It had been closed for years. John put the proposition to Starkey (Roland Starkey, who ran the Shabani and Nil Desperandum asbestos mines). Eventually they formed a syndicate of four members: Starkey, the Nil Mine surveyor, who would be appointed manager and look after the work, Starkey's accountant, and our firm. The syndicate was called "The Bushman Syndicate".

“We put up a 5 stamp mill and started working the mine. We were producing gold, the outputs improving as development proceeded. Starkey paid frequent visits to the mine and generally directed operations. Eventually we came across a good reef and our outputs increased. It became quite a payable proposition and Starkey thought it was worth developing on a greater scale which would require a lot of capital. Just them Edmund Davis (Sir Edmund Davis, a well-known Australian-born mining magnate) was paying a visit to Rhodesia, and Starkey put the Bushtick proposition to him. Harding, the consulting mining engineer to the Nil Mine, went over the Bushtick and produced his report. Acting on this report and Starkey's advice Edmund Davis agreed to float a company with an issue of 5 shilling shares for a capital of £500,000, the vendors receiving 600,000 shares for the property. We started development on a large scale, and as soon as it got known that Edmund Davis was the promoter the shares started going up and before long they were quoted at 15 shillings. We wanted to sell some at this price but the company Secretary, Harrington, told John it would not be right for a director to start selling shares. The mine did very well and for a few years paid some dividends but by the end of 1936 we had sold our shares.”

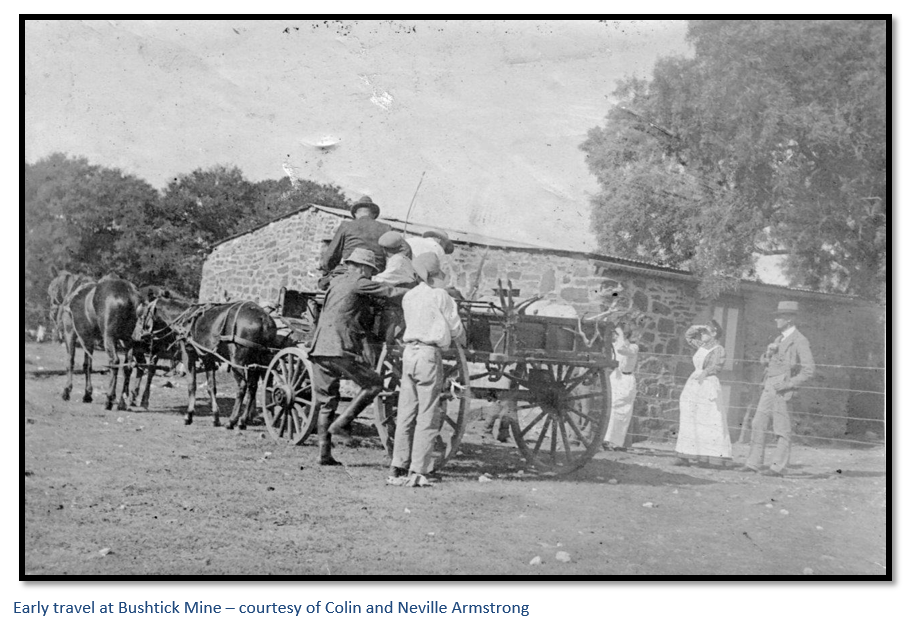

Colin and Neville Armstrong contributed many of the photographs portraying early life in Bushtick Mine. Their great grandfather Captain J.R. “Jack” Warwick was a director and mine manager in the early life of the mine and played a very prominent part in its development. I’m very grateful that they made these family photographs available for me to include in the article

Gordon and Heather Macdonald and Ted Marais were amongst the very few who still knew the exact location of the eighteen room house. As schoolboys we had all suffered completing the ‘eighteen room house run’ even if a great deal of it was done at walking pace, but few remembered its’ location and I am grateful they shared that knowledge.

Mark Sturgeon sent me a copy of an article called Memories of Bushtick by one who lived on the Bushtick Mine from a 1965 edition of The Falcon…this was particularly interesting because it describes the community and social life and all the sporting and recreational activities that were held at Bushtick Mine which many of the employees from the other nineteen small workings within a distance of eight kilometres also attended. Thanks Mark!

Future Prospects

Falcon College has granted rights to Hawkmoth Mining and Exploration (Pvt) Limited (HME) a Zimbabwean company to explore and develop the historic Bushtick Mine and surrounding acreage, including the tailings dumps. Prospects Resources Limited, an ASX listed Australian company, through a Singapore listed subsidiary, owns 70% of HME.

In their annual report to June 2015, Prospects Resources announced it had completed a surface trenching programme of 10 trenches totaling 1,200 metres were dug covering an area of approximately 2kms by 100m over some of the Bushtick Reef. Varying grades of up to 2.8 g/t were recorded with the company stating that with the historical cut-off grades being relatively high, these results looked prospective for mining the remaining ore blocks economically today.

Their results indicated that the area surrounding Bushtick Mine might be prospective for both a small starter open-cast mine and tailings extraction projects, and in the longer-term an exploration programme might identify the greater Reserve Area for a larger open-cast deposit.

Appreciation

For much of the above information I am indebted to Dr. F.L. Amm of the Southern Rhodesia Geological Survey who published Bulletin No 35 concerning the Geology of the country around Bulawayo in 1965. The professional and technical knowledge which it contains is unsurpassed and contributed greatly to making mining such an important sector in the development of this country.

Acknowledgements

F.L. Amm. The Geology of the country around Bulawayo. Bulletin (Southern Rhodesia Geological Survey) No 35

D.J. Bowen. Gold Mines of Rhodesia 1890 – 1980. Thomson Newspapers Rhodesia, 1979

R. Cherer Smith. Sir Digby Barnett K.B.E., J.P., M.I.M.M. Rhodesiana No 35, September 1976 P.19 - 23

R. Summers. Ancient Mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia, 1969

Bushtick Mine (1934) Limited 1939 financial statements at National Archives of Zimbabwe

Mark Sturgeon for an article entitled “The Mine called Bushtick” by an anonymous author in the Falcon College magazine and another called “Memories of Bushtick” by one who was there.

Neville and Colin Armstrong for early photographs of their great grandparents the Warwick Family and other photographs from the early days of the Bushtick Mine.

Gordon and Heather Macdonald for providing details of the location of the eighteen room house and to Barbara and Pierre Heymans for visiting the cemetery and eighteen-room house to take photographs.

When to visit:

Not applicable

Fee:

Not applicable

Category:

Province: