Home >

Matabeleland North >

The Victoria Falls Zambesi River sketched on the spot by Thomas Baines F.R.G.S.

The Victoria Falls Zambesi River sketched on the spot by Thomas Baines F.R.G.S.

National Monument No.:

1

Publishers Introduction

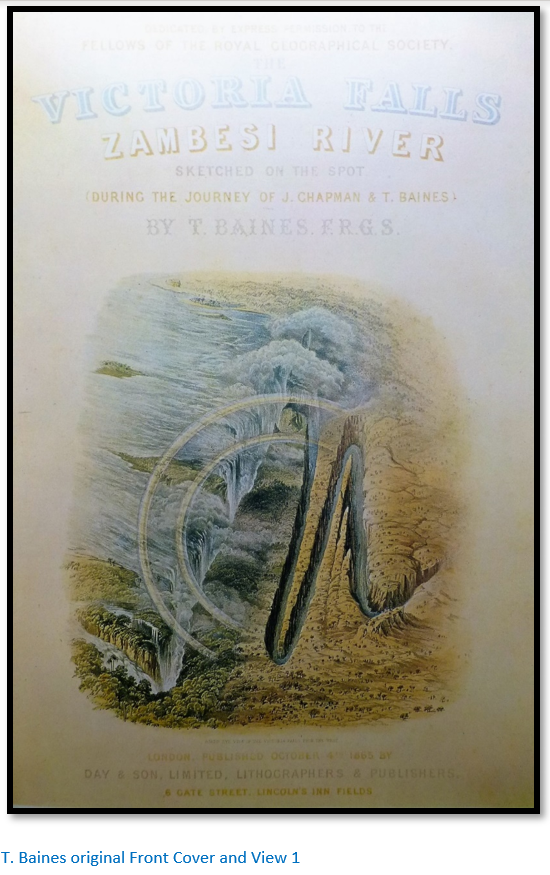

In this facsimile book, probably the finest edition produced by Books of Rhodesia, Louis W. Bolze the publisher, wrote: “Thomas Baines who reached the Victoria Falls in 1862 in company with James Chapman was the first artist to look upon and print this great river wonder. His folio of ten chromolithographs, with illustrated title page and descriptive notes appeared in London in 1866 – the first-ever book of wholly Rhodesian content to be published.”

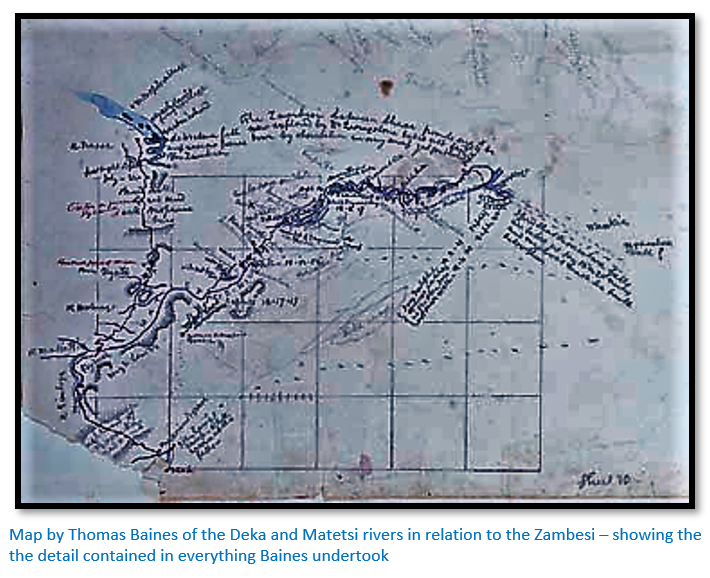

Bolze continues: “Baines was a most prolific painter and more than four hundred of his oils have been traced and scores more are in private collections. His output in water colours and pencil sketches was equally prodigious. The meticulously kept diaries of his extensive travels mark him as an outstanding scientific observer and chronicler and bear overwhelming witness to his industry. But he was essentially an explorer and lover of wildlife who harnessed his creative artistic skills to fulfil his pleasure and give the outside world an authentic and graphic insight into the interior of what a century ago was still darkest Africa.

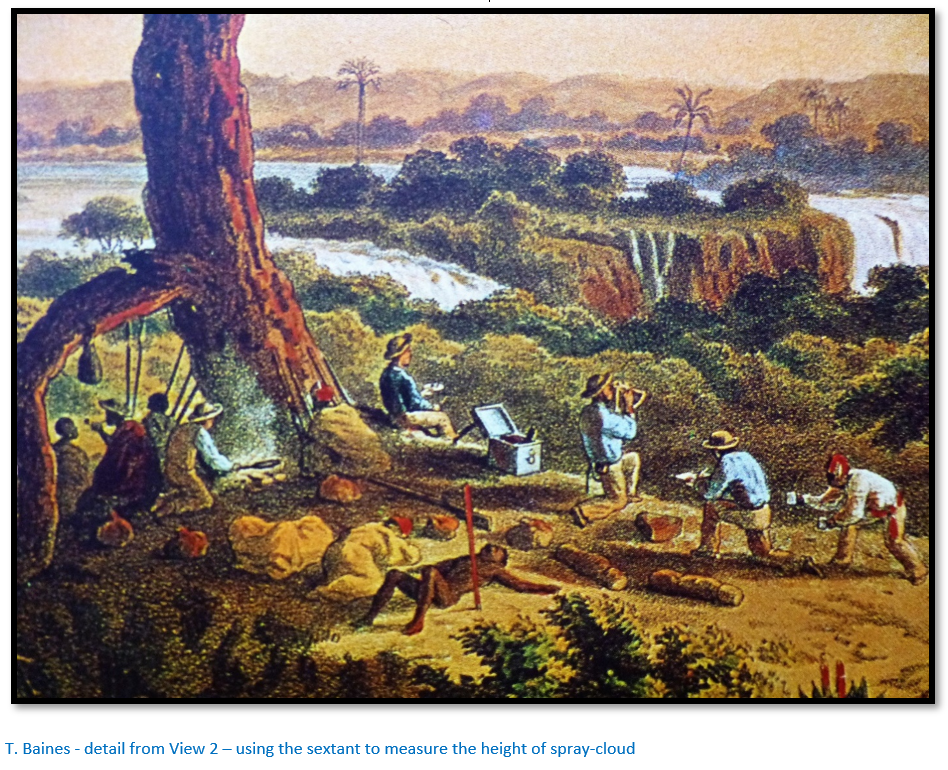

Ever busy with his sextant he mapped large tracts of land, his map of the land mass between the southern coastline of Africa and the Zambesi serving travellers to Matabeleland and Mashonaland until the Pioneer Column of 1890 improved on it. It was once said of him: ‘he was not a man he was a syndicate.’ But the man was a man for all that. Diminutive of stature - he was 5 foot 4 inches, he possessed a strong steadfastness of purpose, a quiet courage and fortitude, admirable versatility and resourcefulness, a warm humanity and physical stamina which saw him through the privations and illness which dogged the early traveller in Africa. Above all he was a man of unfailing good humour, kindness and dignity.

It is typical of his modesty, yet the key to the sincerity and authenticity of his work, that in presenting its Victoria Falls paintings to the public he should have written: ‘I presume not to compete with the works of those who have so beautifully illustrated more accessible countries. In the far interior of Africa, an artist leaves behind every convenience and becoming in turn smith, carpenter, tailor and shoemaker, bullock-driver an astronomical observer, must obtain his sketches and finish his pictures as he can, trusting that any want of artistic finish may be compensated by the faithfulness inseparable from working as much as possible in the actual presence of nature.’

It was also said of him that you travelled with a gun in one hand and a paint brush in the other. This was literally true. Most of his painting was done in moments snatched at the wayside. As for the gun, it was regarded only as a necessary provider for the pot. It was not uncommon for him to sketch wild animals from the saddle, becoming so absorbed in his interest as to be oblivious to the danger in which he often placed himself: ‘I can never get quite get over the feeling that the wonderful products of nature are objects to be admired rather than destroyed,’ he wrote.

Thomas Baines was born at King's Lynn of a seafaring family in 1820 and at the age of sixteen was apprenticed to a local ‘ornamental painter’ to learn heraldic painting. Fired by his father's tales of the Tavern of the Seas, he sailed for Cape Town in 1842 and for a while earned a precarious living as a marine and portrait painter. His appointment as an artist to the Colonial Forces in the Gaika War of 1851-53 provided an exciting outlet for the expression of his artistic yearnings and thirst for adventure and his spirited canvases and sketchers eloquently illustrate many frontier incidents in the Eastern Cape. In 1855 he joined A.C. Gregory's expedition to the Victoria river region of Northern Australia and on his return two years later, he was elected a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and awarded second gold medal.

David Livingstone, much the public idol after his trans-Africa journey and discovery of the Victoria falls in 1855, invited Baines to join his Zambesi Expedition which, in 1857 , made its way upstream to the Kebrabasa [Cahora Bassa] rapids. His post was that of artist and storekeeper and though the hardest working member he was unjustly dismissed by Livingstone on spurious charges in 1859.

Back in Cape Town, he linked up with James Chapman who planned to reach the Victoria Falls via Lake Ngami and travel down-river to the Zambezi mouth. He sailed for Walvis Bay in March 1861 and after a most harrowing journey across the water less desert during which their cattle died of lung-sickness and they were menaced by treacherous Hottentots and Damara tribesmen, they came to the Victoria Falls on the 23rd of July 1862. For the next twelve days Baines explored and sketched the Falls and made extensive geographic observations while Chapman took photographs. They continue downstream to the confluence of the Deka river (Logier Hill camp) but were compelled through illness and lack of food to retrace their steps.

He returned to England in 1865. Three years later he was back in Matabeleland to negotiate a gold-mining concession for the South African Goldfields Exploration Company. His journey from Pietermaritzburg, through Bechuanaland (Botswana) to the precincts of present-day Bulawayo and Hartley Hill is described in the Gold Regions of South East Africa. He obtained a concession from Lobengula but failed to get material backing from his promoters. Whilst in Durban preparing his wagons for another visit to Matabeleland he took ill and died on the 8th of May 1875.

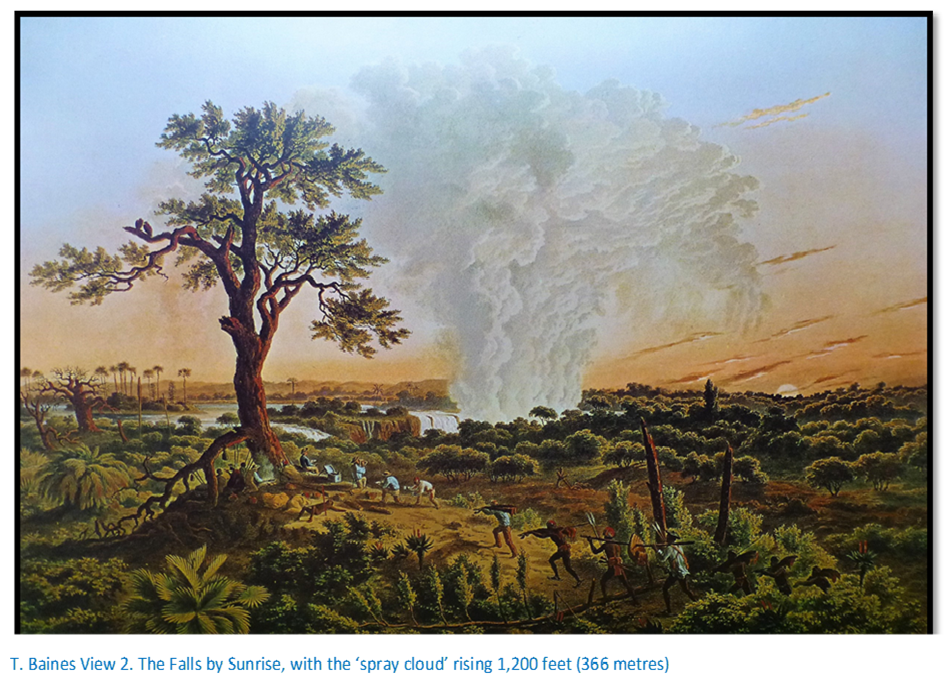

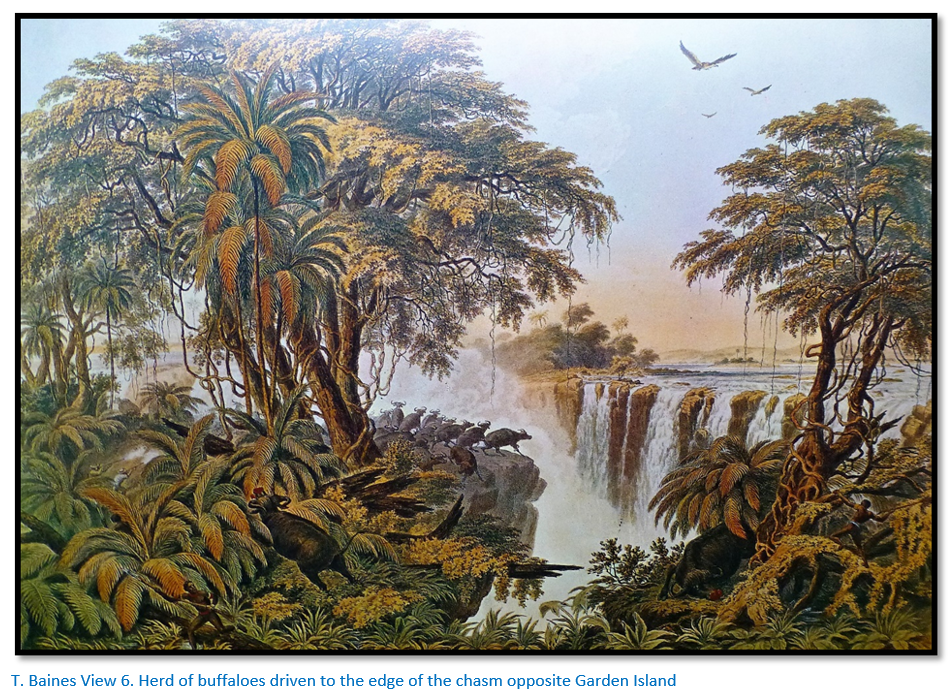

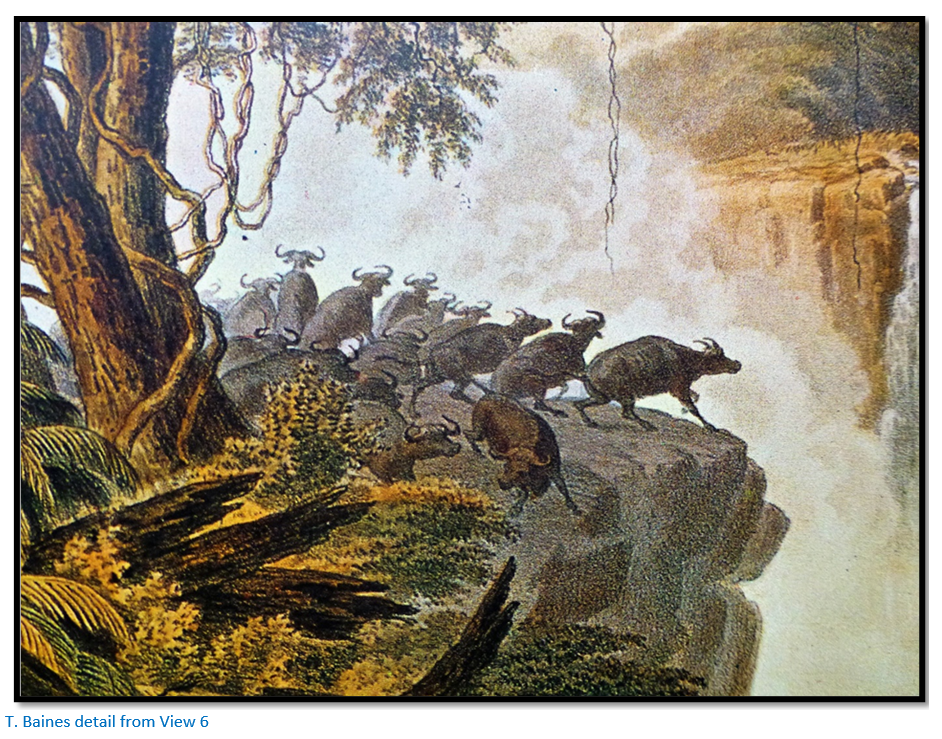

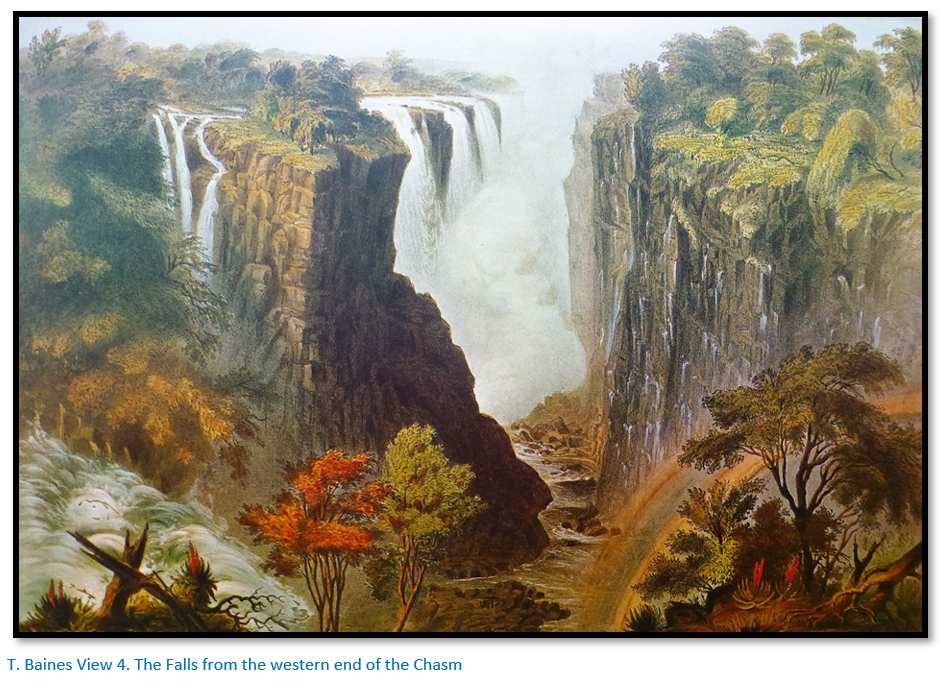

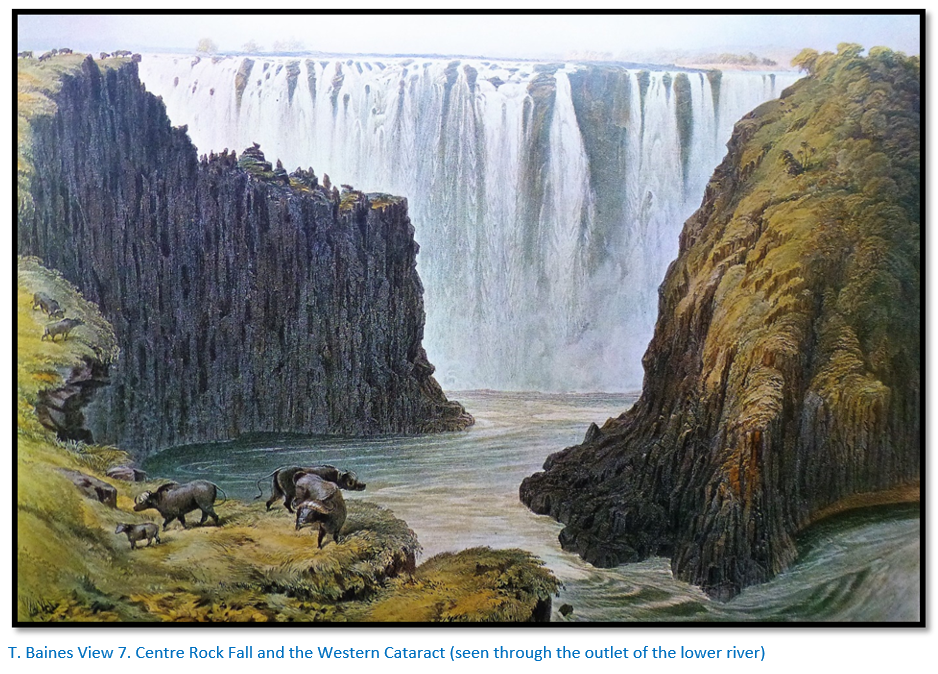

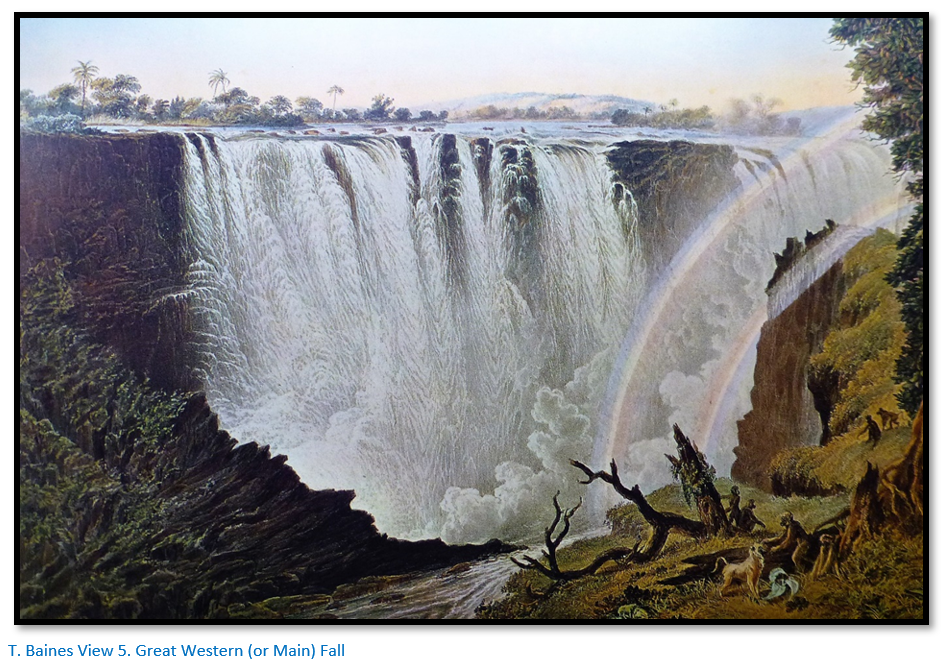

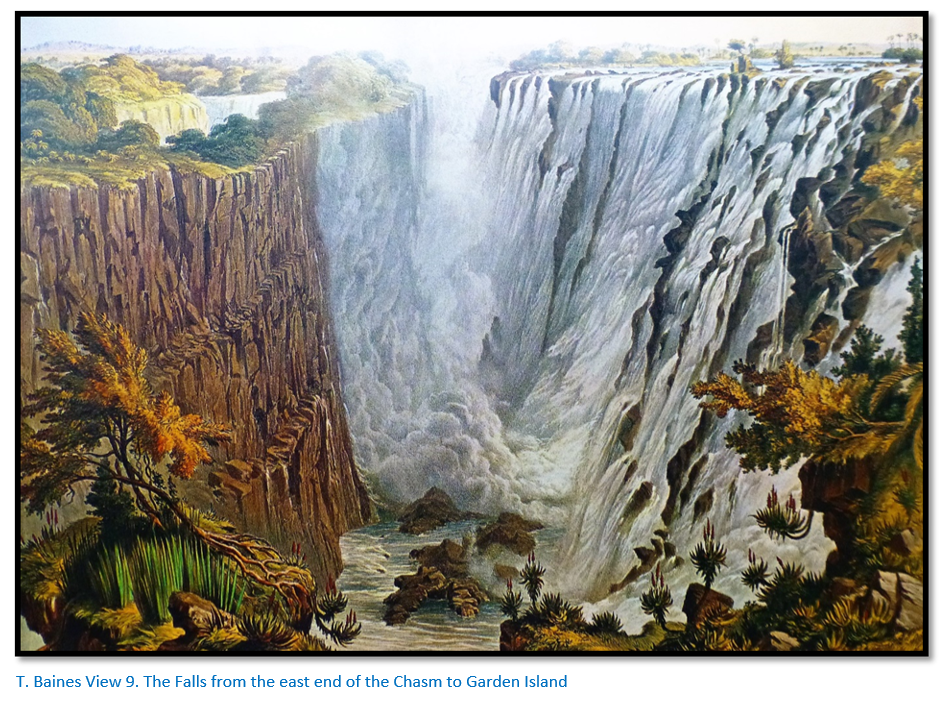

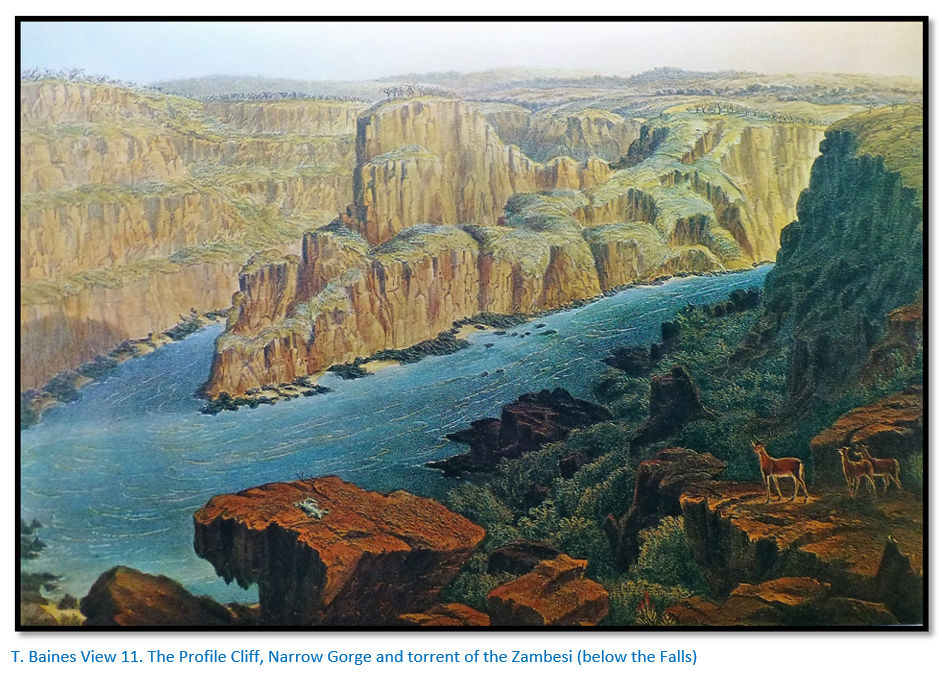

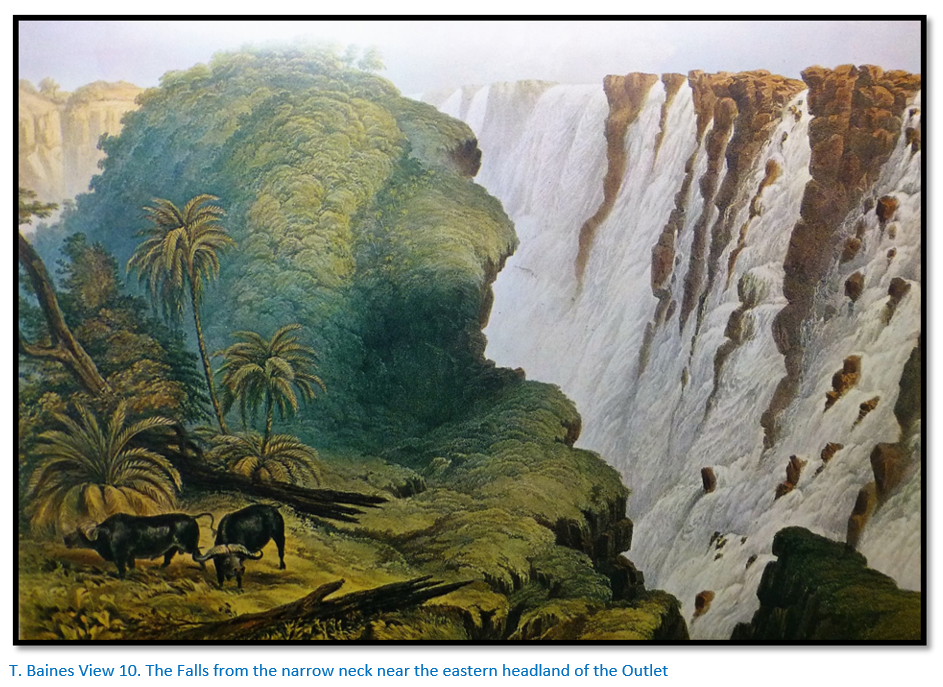

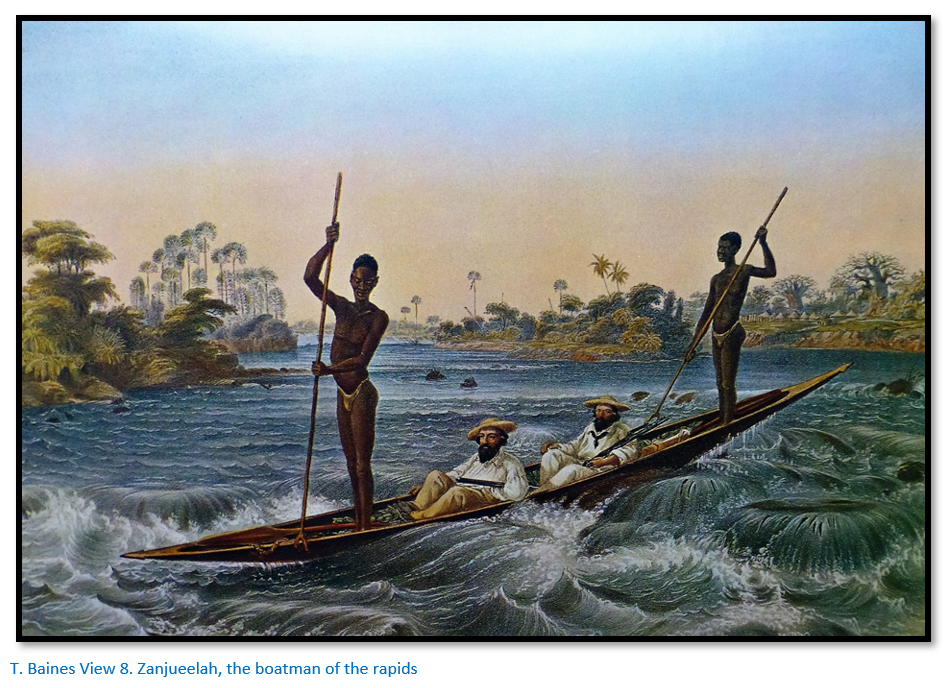

The sketches done at the Victoria Falls were painted as opportunity offered. View 4 was completed at Deka on the Zimbabwe-Botswana border on the 1st of September 1862, which ranks it as the first modern picture painted in Zimbabwe. Views 2 and 6 were finished at Logier Hill camp on 29th of October and the 11th of December 1862 respectively, and ‘Zanjueelah’ at the House of Mr Anderson at Otjimbengue [Otjimbingwe] on 9th November 1863. The paintings were exhibited at Cape Town before being sent to London where, under the sponsorship of the Royal Geographical Society, they were published on the 12th of January 1866 - not on 4th of October 1865, the date given on the folio. There were ‘plain’ and coloured editions, the former being in pale sepia and the latter going through several printings for the addition of tints. Extra colour was added by hand. The facsimile reprints were printed from colour transparencies of the folio reproductions kindly provided by the National Archives of Rhodesia and made from two different copies of the ‘coloured’ edition. Artistically the original book was just regarded as the most impressive of Baines’ publications, despite the limitations of chromolithography. But the subscription list was meagre and instead of receiving profits Baines have to pay for his presentation copies.

Where are the paintings?

In 1969 the original paintings were situated as follows:

| View 1 | National Archives of Zimbabwe |

| View 2 | Bulawayo Club |

| View 3 | National Archives of Zimbabwe |

| View 4 | National Archives of Zimbabwe |

| View 5 | Unknown |

| View 6 | National Archives of Zimbabwe |

| View 7 | National Archives of Zimbabwe |

| View 8 | National Archives of Zimbabwe |

| View 9 | National Archives of Zimbabwe |

| View 10 | Bulawayo Club |

| View 11 | Royal Geographical Society |

Baines almost entirely self-taught, was a truly creative artist . Despite his isolation from art centres of the world and the adverse conditions under which he toiled, he painted with a structural energy of composition and technical inventiveness becoming of Paul Cezanne, the most significant master of the nineteenth century. Much travelled on water, Baines was skilled at representing liquid movement. His Falls paintings faithfully portray the gradations of mood from gently swirling eddies to the surging, pounding grandeur of the leaping waters with their gossamer spray and captive rainbow. So detailed is his brushwork that it is possible for a botanist to identify the various types of vegetation depicted.

The indifference of his contemporaries to his work was but another disappointment which he bore with fortitude. Ill-used by those who he served well he is seen in the perspective of time to have been a noble character wrought of the finest mettle. His living pictures of Mosi-oa-Tunya will give pleasure long after the beholder has moved from earshot of ‘The Smoke that Thunders.’ In giving a new lease of life to these paintings, through the facsimile reprinting, the publishers hope to promote a deservedly wider appreciation and recognition of the rich heritage left by this industrious and talented pioneer.

Bulawayo, December 1969 Louis W. Bolze

This account of the Victoria Falls is from Thomas Baines’ Explorations in South-West Africa: being an account of a journey in the years 1861 and 1862 from Walvisch Bay, on the Western Coast to Lake Ngami and the Victoria Falls

The popular idea of Africa has long been that its interior was a vast desert. The traditions of inland waters were discredited and in 1849 Lake Ngami was erased from our maps at the time it was being discovered in te very place native reports had assigned to it.

Nevertheless those who held communication with the half-caste traders or had access to the early Portuguese records knew that extensive lakes and river systems were to be found there. In Ogilby’s Africa, published in 1670, the map shows two great lakes nearly corresponding with the Victoria and Albert Nyanzas with branches of the Nile flowing from them and the Zambesi is given nearly in its true position, though the Manice or Rio de Spirito Santo is erroneously connected with it. The Atlas Geographus in 1714, less correctly even that the earlier record, describes the Lake Zambre as the common source of the Nile, the Cuama (or Zambesi) the Manice and the Zaire or Congo on which are ‘cascades in the middle of its channel falling from rocks with a noise that me be heard two or three leagues off.’

It has for some time been known that within the southern tropic and nearly equidistant between the eastern and western coasts, the course of the great Zambesi was interrupted by similar falls; and in 1852 or 1853 my long-known and highly-esteemed fiend Mr James Chapman who crossed the continent of Africa in those years had engaged a canoe and was embarking for a visit to the Falls when the crew were recalled by Sekeletu their chief and he was obliged to forego the honour of being their discoverer. In 1855 they were seen by Dr Livingstone who was then preparing for his journey to the east coast and was the first to bring them to the notice of the British public.

Various branches of the Zambesi appear to rise not far from the west coast and flow through country so level that they give off, as well as receive, other streams of which it seems probable that the Okavango river, discovered in 1859 by that enterprising traveller and naturalist Mr C. J. Andersson is one of the principal, til the river reaches nearly the centre of the continent.

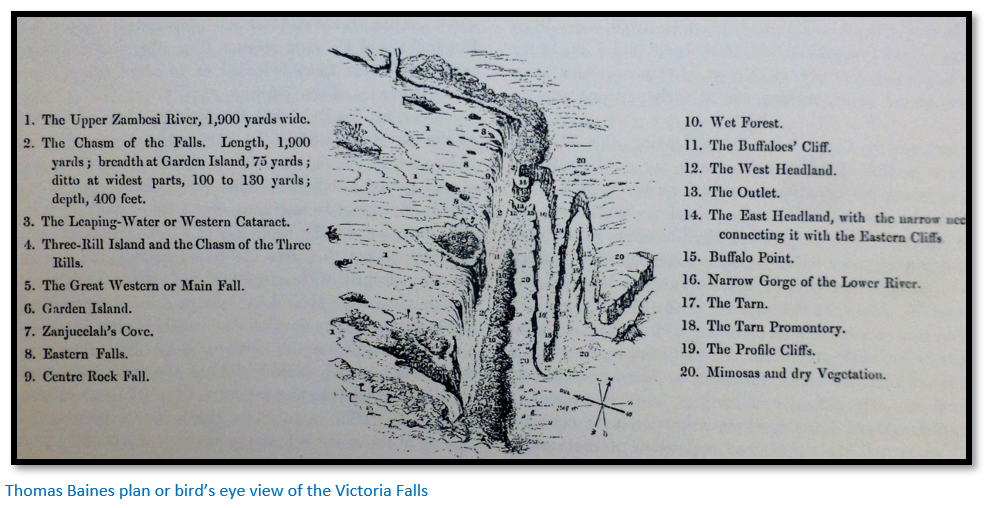

Here the Falls are formed by a deep narrow chasm cleft across the broad bed of the river, which, plunging four hundred feet into the abyss, escapes by another cleft joining the first at nearly three-fourths from its western end and prolonged in abrupt zigzags and redoubling for many miles engulfing the narrow lower river far below the surface, occasionally spreading out and again contracting; traces of the fissure appearing, as it seems to me, nearly to the Indian Ocean or more than eight hundred miles away.

Above the Falls where the river is nearly on a level with the surrounding country, rich tropical vegetation abounds and long reaches are descended on rafts, or navigated in canoes, almost the only difficulty being occasioned by the thick growth of reeds in the shallower portions.

Below them no continuous navigation is possible for eighty or a hundred miles; but beyond this, long open reaches alternate with occasional rapids and narrow gorges, the most dangerous being those of Chicova and Kebrabasa, in which my friend Dr Kirk when descending the river, very narrowly escaped drowning.

In presenting to the public the accompanying views of those magnificent Falls, I presume not to compete with the works of those who have so beautifully illustrated more accessible countries. In the far interior of Africa, an artist must leave behind him every convenience and becoming in turn smith, carpenter, tailor and shoemaker, bullock-driver and astronomical observer must obtain his sketches and finish his pictures as he can, trusting that any want of artistic finish may be compensated by the faithfulness inseparable from working as much as possible in the actual presence of nature.

It is also difficult in the description to avoid some little repetition of my journal already published and I ought to acknowledge the courtesy of Messrs Longman who have kindly consented to my making use of such parts as may be required.

Returning to Cape Town after leaving the Zambesi Expedition in 1859, I found refuge with my steadfast friend Logier, by whose kindness I was enabled to devote all I could accumulate by my art to the purpose of my equipment for another journey. Here I again met Mr Chapman who was at that time preparing for an expedition to the interior and we agreed to attempt the passage from Walvisch Bay on the west coast of Africa to the mouth of the Zambesi on the east. For this purpose I built with my own hands two boats of copper to be used either like South-sea canoes, with a deck between them, or singly, should it be found necessary to separate them. The difficulty of carriage however caused by fearful ravages of infectious lung-sickness among my companion’s oxen and the consequent opposition of the various tribes to our passage, as well as the impossibility of procuring other wagons at any price I could afford to pay, obliged me to leave eight out of the twelve sections at the village of Mr C.J. Andersson at Otjimbengue.

For sixty miles from the sea our path lay through shifting sand and arid desert but the oxen found refreshment from the scanty herbage in the deep ravine of the Swakop river where, rolling its immense leaves over the dry sand, I found that marvellous plant the Welwitschia mirabilis, the first sketch and specimen of which ever seen in England I had the honour of sending home. Nor is the country just beyond more destitute of interest; for there midst rugged hills of disintegrated granite I sketched the gigantic aloe, the circumference of whose trunk is nearly twelve feet, while its spreading crown of leaves, adorned with countless spikes of yellow flowers attains a height of more than twenty-five feet.

Still further on, near the Koobie in the Bushmen country, Chapman brought to my notice a little bulb, the bud of which, exploding after sunset, presented a bell-shaped flower of the most delicate and semi-transparent white, diffusing its gently refreshing odour at intervals throughout the night and withering before the heat of the next day.

Passing south of Lake Ngami and hugging the reedy banks of the Botletle river as long as possible we struck more northerly across the elevated desert where for nearly two hundred miles not a drop of running water meets our view and the cattle drink at scanty rain-pools scattered few and far between in clay or limestone hollows.

Suddenly emerging from the forest of Mopanis the dry foliage of which so long has limited our view, a blue horizon appears before us and standing at an elevation of three thousand five hundred feet we cast our glance over a seemingly illimitable valley where the brown and fire-scathed ridges beneath our feet give place to others, passing through every shade of sombre green and greyish purple, dark forest alternating with grassy sward, til they are lost in the ethereal blue of the far-off horizon, while from every hollow gushes forth some bubbling rill to send its waters to the great Zambesi.

Large herds of buffalo frequent the swamps and forests, the rhinoceros wanders in the solitude of the mimosa glades, and here we found the magnificent sable antelope and numerous specimens of a full-striped quagga which had first been shot by my friend upon the table-land behind us and which, if not a new species, seems at least an intermediate variety between Burchell’s and the true zebra. Here also the deadly-winged cattle pest – the tsetse fly – forced us to adopt other means for the continuance of the journey.

Crossing the Daka [Deka] and Matietse [Matetsi] and leaving our vehicles on the Onyati or Buffalo River near the wagon of an ambassador sent by Sichele to demand from Sekeletu the restoration of the goods plundered from the ill-fated mission-party of Messrs Price and Helmore, we discarded everything that could not be carried on the shoulders of a few Makalaka and commenced our march across the tsetse-stricken hill of red sand, scantily clothed with mopanis and other varieties of the Bauhinia perking their leaves in pairs edge upward, defying the sun to scorch or the traveller to find shelter beneath them.

We halted on the northern slope beneath a spreading mochicheerie and while watching the red glare of our fire thrown high into the dim recesses of the foliage, heard, stealing through the stillness of the night, a low murmuring like the sighing of the ocean before a gale, rising and swelling gradually into the deep=toned, monotonous roar of a continuous surf for ever breaking on some iron-bound coast.

On Wednesday 23rd of July 1862 we were in motion soon after sunrise and had barely preceded half-a-mile when Barry discovered the smoke and seeking a little opening through the trees we saw the water of the broad Zambesi, glancing like a mirror beyond a long perspective of hill and valley, while from below it clouds of spray and mist, more than a mile in extent, rose from the chasm into which the water fell. The central five or six of these were the largest; but in all we counted ten, rising more like the cloud of spray thrown up by a cannon-ball than in a strictly columnar form. A light easterly wind just swayed their soft vapoury tops; the sun still low, shed its softened light over the sides exposed to it, the warm, grey hills beyond faded gradually into the distance and the deep valley before us, winding for six miles between us and the falls, showed every form of rough brown rock and every tint of green or autumnal foliage, presenting to the eye long wearied of sere and yellow mopani leaves, dry rocks, burnt grass and desolated country, the most lovely coup d'œil the soul of artist could imagine. Willingly would I have feasted my eye upon this distant vision for the day.

And now was to come before our view another portion of the panorama, to the hungry native of far more interest than all the cataracts the world can boast. We had refreshed ourselves at the Masoe, a little stream flowing over a rocky bed and started with fresh vigour on our way, when our guide whistled. A halt was made and every eye turned in the direction indicated; a black rhinoceros, the fiercer of the two varieties, was standing not far upon our right, and by his uneasy gestures it was evident he had caught sight of us at the same moment.

Keeping back as well as we could our excited followers, Chapman and I crept to within fifty yards and fired with deadly aim into his shoulder. He stumbled, badly wounded, but stood at bay a hundred yards further, viciously snuffing the air with elevated nose; a couple more shots brought him down again with a broken shoulder, and bleeding profusely from the lung he darted away through the thicket at a pace we could not cope with. We ran till out of breath when the spoor was plain, or sort its course in devious windings when it was not; we crossed the little river and about four miles back caught sight of him again, but the rush of the three men who had kept up with us put him to flight and we returned leaving two to follow silently and find an opportunity of despatching him.

We broiled a bit of elephant flesh on the embers and took the path again, winding wherever soft red sand could be found among the rocky hillocks. Pebbles and crystals of quartz, red, white and green (though the latter does not test like copper) agate, coarse red jasper and black scoriae, looking as if they been cast from a furnace, lay about the hills. The deep narrow chasm of the lower river, doubling in abrupt zig-zags in the broad valley, enriched with every kind of foliage, had now become more decided in its character, steep cliffs enclosed the narrow stream on either side, the deep shadows of the precipices contrasting with the plateau above, whose yellow surfaces showed like fields of ripened corn. Immediately beyond was the belt of dark fresh green forest fringing the ravine of the Victoria and from behind this rose the white vaporous spray clouds from which the Falls derive the name of Mosi-oa-Tunya (or smoke that thunders) screening as with a misty veil their now darkened southern face, beyond which a long vista of the broad, palmy, island-studded upper river glittered like silver in the sunlight, the banks showing in warm and grey tints the detail of their features and the mountains melting faint and blue into the distance.

The increasing thickness of the forest as we approached the better-watered country of the upper river, shut out from our view the transient beauty of the scene, and turning north, amid tall mochicheerie and ana trees, varied by funereal-looking motsouries, date palms, the wild and almost inedible variety, with their graceful drooping foliage, low fan palms offering in contrast their pointed leaves, baobabs, those giants of the forest (sometimes one hundred feet in girth) and tall palmyras towering over all, the path brought us to the westward of the falls and about a mile from their nearest point.

We camped down under a shady tree, took two or three Makalakas to carry gun and sketchbook and walked down to make sure of a preliminary view and settle the plan of future operations.

The moistened atmosphere to leeward of the spray cloud, the rich green sward becoming momentarily damper til every footprint of elephant, hippopotamus or buffalo was filled with fine clear water, marked our near approach and crossing with sodden shoes the rotting stumps and half-fallen trees that obstructed our view, we stood at once fronting the southern face of the magnificent Victoria Falls.

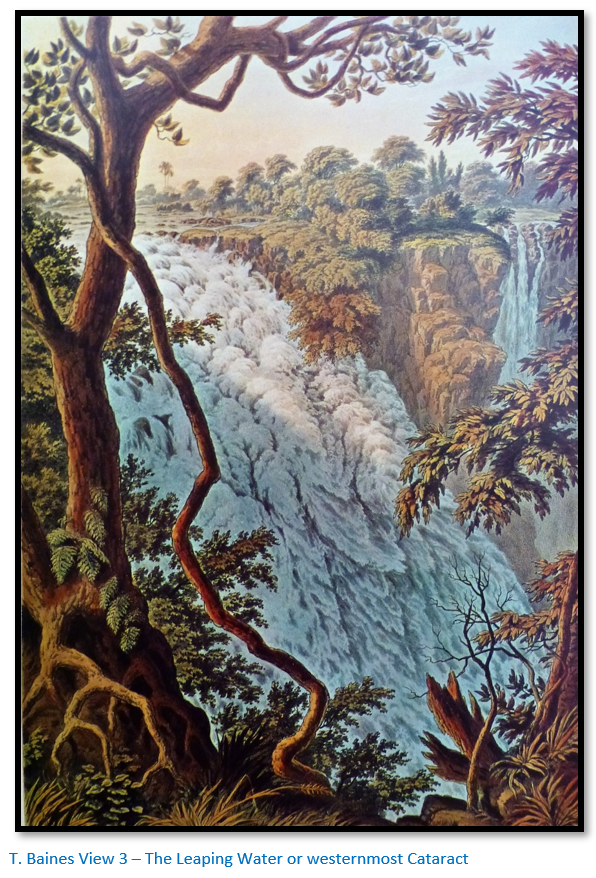

At the western angle, or just opposite to us, and at the beginning of the ravine, a body of water fifty or sixty yards wide comes down like a boiling rapid over the broken rocks: the steepness of the incline, while it diminishes by a few feet the height of the actual fall, forming a channel for the reception of a greater volume of water and allowing it to rush forward so much violence as to break up the whole into a fleecy, snow-white, irregularly seething torrent, with its lighter particles glittering and flashing like myriads of diamonds in the sunlight, before it takes its final leap sheer out from the age of the precipice into the abyss below.

Then interposed a mass of cliff, smooth almost as a wall, and certainly as perpendicular, its base projecting like a buttress, its summit crowned by grass and forest kept ever dark and green by the spreading mist, and its dark-purple front (deepened almost to blackness in the shadow by the northern sun) broken by a deep chasm through which poured three smaller rills, that might have been accounted grand had they not been dwarfed by the mighty mass beside them.

A hundred yards more east commenced the first grand vista of the Fall, comprising in one view near half a mile of cataract stretching in magnificent perspective from the Three Rill Cliff to the western side of Garden island.

The cliff was here of its original height, and the edge being apparently unworn, the height of the fall was greater, while the depth of water flowing over it was less: besides this, from the absence of any material slope like that in the channel of the Leaping-Water, the stream did not gather way, but flowed calmly and majestically onward.

Shallows and ledges of rock caused rapids and miniature cascades, but these only partially broke the repose of the deep blue surface; til reaching the cantle of its course, the mighty change took place. Wherever an inequality of the rock formed a hollow to conduct a mass of water, there fell, sweeping more or less outward in direct proportion to its strength and volume, a jet more or less green and translucent for the first few yards, but quickly breaking into masses from which the lighter particles, detached in their descent, formed comet or rocket like trains of spray and vapour, til the whole, before reaching the abyss, was transformed into a broken snow-white fleecy stream, bearing but little resemblance to actual liquid water, and reminding me more of the descriptions of the Staubbach, in the Alps, than anything else.

The river was at its lowest and the sheet of water broken by projecting rocks: but I suppose it never can present the smooth unvaried regularity which the only representation hitherto given would indicate. Here and there masses of rock jutted out, their tops forming small islands, breaking the uniformity of the line, and their fronts interposing broad faces of dark rock, on either side of which trickled down shallow rills too weak to jet out in curves like the others. Some of those never even reached the bottom in a visible form, being either distributed over the rock, or dispersed by the wind that always eddies upward from the gulf.

Now stand and look through the dim and misty perspective til it loses itself in the cloud spray to the east! How shall words convey ideas which the pencil even of Turner must fail to represent? Stiff and formal columns of smoke there are none: the eastern breeze has blended all in one. Think nothing of the drizzling mist but tell me if heart of man ever conceded anything more gorgeous than those two lovely rainbows, so brilliant that the eye shrinks from looking on them, which rising from the abyss, deep as the solar rays can penetrate it, overwatch spray, rock and forest, til at the highest point they fail to find refracting moisture to complete the arch.

Eastward Ho! Still eastward through mud, wild date-palms, grassy swamps and vine-tangled forests with ever dripping leaves, scene after scene of surpassing grandeur presenting itself, til the imagination is bewildered and embarrassed by so much magnificence. Now we pass the central , or as we suppose it, Garden Island, dividing the fall into two great masses, and interposing its breadth of bare projecting precipice. Its extent as yet we cannot tell, for its farther end is lost in spray. In some places the forest reaches quite to the verge, the trees appearing as if the keen wind blowing upward from the gulf has shorn off their overhanging branches level with the cliff. Here and there are broad intervals of dark purple rock, wet and slippery with gelatinous weeds. I approach the edge and look with awe into the troubled narrow stream beneath. The influence of the water rushing down, eternally down, seems to meet a response within me and kneeling down, I rest one hand upon the edge to look further; but now comes my little Bush-boy to rescue me from the supposed danger, nor will he be satisfied til we have removed from the verge.

Again our progress is checked and our attention called from the glories of inanimate nature to the necessity of guarding against other emergencies of the wilds. The open sky beyond shows that we have nearly reached the termination of the forest, when Chapman stops suddenly. I see nothing yet, but the poised rifle and attitude of precaution show that something more than ordinary is before us. I step backward, round the corner of a bush and there within seventy yards are a hundred buffaloes: fortunately to windward of us. We fire into them and they charge wildly round to leeward seeking to sniff our wind. If they gain this, their next charge will be directly at us. Bullet after bullet stops and heads them off and though they see us plainly, they cannot determine on a direct charge without another effort to get to leeward and ascertain our quality by the scent. At length they turn and rush towards the Fall, crushing through palm break and rotten timber til, at full speed, they gain the rocky headland and we hold our breath in momentary terror lest they should rush over. Now they halt on the very edge, their dark massive forms stand out in bold relief against the misty clouds and again as the bullets tell upon them, they take refuge in the palm break, the wounded lagging in the covert as they go.

One with bleeding jaws charges directly at us forcing us in turn to take shelter behind the stoutest trees and presently my little fellow calls my attention to one standing crippled between the feathery leaves of a palm and a diagonally stunted tree. As I prepare to fire, he rises to charge and I take cover til I estimate his remaining strength, returning to deliver my fire when his fruitless effort is over, the Bushman immediately climbing the tree and throwing his assegai from the branches, while a Makalaka, carrying an empty musket, begs hard for a charge and a bullet, which is refused only because we have none to fit the bore.

Still there are others badly wounded in the brake – invisible, though we can hear them bellowing within ten yards and extreme caution is necessary in approaching so dangerous a beast. Chapman, as the more experienced hunter, now takes the lead and I follow closely to support him. Peering closely through the openings of the arching leaves at length he sees the feet and firing shot after shot where he thinks the body ought to be, retreats to cover after every discharge. After a while all is silent and leaving the animals to die, we secure part of the flesh of our first victim and hasten to cheer the hearts of our party with tidings of the glorious feast awaiting them.

A second encounter in the more open country with the herd retreating from the Falls and reinforced by a much larger body coming down to enjoy the spray-shower, resulted in the death of a fine cow, making a total of six killed during the day, besides the rhinoceros which can hardly escape the keen-eyed natives, who watch the hovering of the vultures and seldom think it necessary to trouble us with information of game that dies at a distance from our camp.

A couple of fine men, bearing the large heavy spears used on the river, arrived soon after, having been sent by Moshotlani, the petty chief of the ferry, to learn the object of our visit. Chapman answered that, knowing the wish of Sekeletu to engage in commerce with white men, he had brought up a few goods for preliminary traffic; but as land-carriage was long and tedious and the loss of cattle by lung-sickness and tsetse-fly heavy, he wished to hire ten men for such pay as may be agreed upon to assist us in building a boat near Sinamanes to navigate the river down to Tete, whence goods could be brought up at prices more nearly in accordance with their original cost.

The death of the unfortunate missionaries was a delicate subject for persons situated as we were to touch upon; for we cannot exonerate the chief from having hastened their death by harsh treatment and neglect, if not, as native testimony assures us, by actual poison. Certainly he plundered the survivors and insulted them by disinterring and brutally mutilating the corpses of their dearest relatives.

In answer to an allusion on the subject, we told them it had been reported in Cape Town that Sekeletu had poisoned them and that the people were grieved and indignant at the cruel deed; but we were private men and had no authority to speak on so serious a subject which had better be left to be discussed between the chief and such persons as might be delegated by our Government.

At night I observed stars which gave the latitude of the Falls as 17°55´4"south.

Thursday 24 July 1862

Wakened about daybreak by the never varying unceasing roar of the cataract we saw the dull grey spray cloud rising in irregular columns and spreading its dark form against the eastern sky, differing from smoke only in that it did not rise or fall beyond a certain limit and did not drift away, but remained overhanging the spot from which it rose, its spreading palm-like top just swayed and altered by the gentle south-east breeze. I watched with interest as the sun rose about 30° on one side of it but was somewhat disappointed in the effects I had anticipated. No play of brilliant colours took place on its illuminated edge, nor did it show more transparency or light and shade than a diffused cloud of steam under the same circumstances. Its angular height, measured with the sextant, varied from 5°50´to 7°48´ which, estimating our distance at one mile, gave with 90 feet for the height of the trees and 350 feet for the depth of the fall, nearly 1,200 feet as the actual height to which the spray rises from the bottom of the chasm.

This is, of course, only an approximation, and it must be remembered that the height and apparent volume are greatly diminished as the heat of the day comes on, while during the coolness of the early morning we thought it rose higher. In the wet season, when the flood rises six feet or more, it must be truly magnificent; and in fact Chapman has since seen it from a hill more than fifty miles distant.

Shifting the camp to the ferry landing, about a mile higher up, I returned along the bank of the river with my young friend Edward Barry, getting peep after peep at the water as from a swiftly-flowing stream it grew into a rapid, rushing with accelerated violence as the slope increased; til, at length we stood over the very edge of the westernmost channel and looking down on the broken foaming mass tossing in wild confusion beneath our feet, could see still further down, the troubled water in the deep chasm making its way toward the east and as the clouds of misty spray swayed and opened, could catch glimpses of the remoter falls nearly as far as Garden Island. Edward seemed rapt in wonder and was ready to declare that nothing could be grander; but when a hundred yards more brought us round the western end of the chasm and face to face with the white and foaming mass of the Leaping Water with its minute particles glittering like flakes of silver in the morning sun, he could not find words to express his feelings.

We passed the scene of our battle with the buffaloes, where clusters of wild date-palm shot up their slender stems and graceful feathery leaves to a height of thirty or forty feet; while others, shorter in the stem, spread their leafy crowns so as to form a dense and almost impenetrable jungle in the recesses of the swamp.

The forest now terminated abruptly; and determined to see the end of the Falls this time, we walked on through swampy grass, til we were stopped by a deep fissure – not at the end; for we could still see waterfalls melting into obscure mist more than a quarter of a mile beyond; but, as I suppose, nearly three-fourths from the western end. Impressed with ideas founded on Dr Livingstone’s picture and description, we thought at first that this must be one of the rivers we had seen on Wednesday; but a glance from the precipitous headland at the narrow stream far down in the gorge beneath us showed that it was the outlet of the Zambesi itself and that the waters of the cataract were flowing from the east end, as well as the west, to escape by it. I did not like at the moment to decide that no outlet could exist at the extremity of the fall; but it was evident that, if there were, only a small portion of water could flow through it and I subsequently found there was none.

The stream was of that sombre green that indicates great depth, the moderate rapid formed in the narrow turn below the entrance rolling in that smooth glassy swell almost destitute of foam, which seems so gentle, and proves so overpowering when one tries to stem it. I could not at that time tell of the impediments that existed further down, but it seemed to me that, if that swell could be surmounted a stout crew might pull a whale boat right into the chasm and even skirt the base of the fall for a short distance to east and west, before the rapids and shallows stopped them.

Saturday, 26 July 1862

Chapman and I spent the day in photographing and sketching the chasm from the brink of the rock overhanging the rapid of the Leaping-Water at its western end. The view here was magnificent, though the volumes of spray and mist projected from the foot of the fall and rebounding from the opposite cliff compressed into rolling clouds such as might arise if the broadsides of a fleet were discharged in the same limits, hid from us all but a small portion of the nearest actual fall. Still in the space kept clear by the interposition of the dark sombre wall of Three Rill Island, we could see far below us the troubling eddying stream, dark green and of glassy smoothness in the deep pool, or white and foaming as it encountered the numberless rocks and shallows in its way; seeking as it were to escape by the only channel open to it from the rush and turmoil it had passed. At this, which may be called the beginning of the chasm, the rock of Three Rill Island on the north or upper side, projects at its base like a huge buttress and heaps of great fallen masses still further narrow down the watercourse; but there is no corresponding indentation in the lower part of the opposite cliff, which, on the contrary, has two or three horizontal ledges showing that more of the upper than of the lower part must have fallen off, we therefore think that a wedge-shaped mass, widest at the top, must either have given way in the form of debris at the time of the disruption. Or have been then so shaken and fractured as to be washed down gradually afterwards. The west end of the great chasm falls back about fifty yards and the sloping channel of the Leaping Water and the chasm of the Three Rills beyond it have also contributed their fragments to the heap at the bottom of the cliffs forming several marked shallows across the lower stream and from the general appearance we concluded that if the fissure at its western end has ever been any great depth beneath the surface of the lower waters, the broken rocks have so far filled it up that it must now be comparatively shallow.

The slope already mentioned in the Leaping-Water channel. Carrying off a deeper stream causes it gradually to become a foaming angry rapid, til with the impetus it has acquired, the water broken and glittering like a shower of living diamonds in the sunlight, leaps clear away from the edge and shoots diagonally downward in masses which may be likened to the nuclei of comets, leaving long vapoury trains in their rear, whilst the Three Rills – which if not contrasted with this mighty fall would be themselves be called cataracts – find their way through rock and forest on the top and gushing down a perpendicularly as the jutting irregularities allow, fill their hollow with an indefinite grey mist, which nothing but a vertical sun at another period of the year can illuminate.

The wind, the waving foliage, the drifting spray and above all, the impossibility of catching the details of the rushing water were sore trials for the photographer, and to say truth, not much less was the artist made to feel the incompetency of his power to give even a faint idea of the grandeur of the scene before him. Still it seemed not quite impossible til the declining sun caused the rainbow to rise from beneath his feet and gradually to span the entire picture, drawing its tints, more beautiful than England’s clouded climate one can even dream of, over rock, spray-cloud, waterfall and forest. Then indeed the combined effect of wild and sombre magnificence in the eternal cliffs, the life-like motion of the of the leaping or the inert declension of the falling waters, the inimitable softness of the misty cloud veiling the distant precipices , the vivid yet blended tints of the dense forest, and above all, the surpassing loveliness of the brilliant bow, could not but impress him with a deep sense of the nothingness of human art in the presence of this mighty work of the Creator.

Monday and Tuesday 28 and 29 July 1862

I repaired to Buffalo Point , the promontory in the first bend of the outlet, and sketched as carefully as possible the portion of the eastern falls visible through the dark portals. On my left appeared the precipice from the very peak of which Barry and I had first looked down upon the scene, and from which, about two-thirds of its height, a thin wall of black cliff jutted out; still further encroaching on the narrow opening and on my right was the eastern headland, crowned with forest trees and date-palms and broken more than half-way down into rugged slopes, on which rank grass and hardy bushes seemed to struggle for a foothold, while the dark rocks at its base formed a convex line which looked as if it might again be fitted into the opposite hollow; beyond this a small bay, wooded almost down to the cliffs upon its beach receded so far that the headland stood out in bold relief, connected as it seemed, only by a narrow promontory with the eastern shore.

Subsequently I spent another day making a careful study in oil colours of one of the small cataracts in this scene ( which for the sake of distinction, we called Centre-rock Fall) and though my picture looked poor enough in the actual presence of the Falls, it seemed much more satisfactory when seen at our bivouac, more than a mile away.

On one of these occasions, Bill, one of our Damara boys, without any orders from me had boiled the kettle, cooked me a mess of beans and with a bit of heavy cake brought from the camp. Set out a nice little picnic tiffin under the shadow of a tree, an agreeable variation in the day’s work I had never thought of before, probably for want of someone careful enough to do it. Poor Bill seems to have more appreciation of beauty than I have observed in any of his country people. As soon as he had overcome the nervousness of first looking over the edge, he laughed and clapped his hands with childish glee at the rushing waters and when I sent him into the mist to see the rainbow, he not only stayed for some time, but called Roode Baatjie also to admire it. While I was taking angles as far as objects could be seen through the spray cloud, I sent them both to try and find a path to the bottom, but they did not succeed. We saw a pair of beautiful birds, in form and size like toucans (probably hornbills) but of a deep blue or purple, with the ends of the quill feathers white, forming when the wings were spread, a transverse line right across.

The grey ghostly forms of the baboons glided as usual amongst rocks and forest, but so cautious were they and wary, that though we should have been glad of one for supper, I could barely obtain a passing glimpse of these grotesque caricatures of the lion.

The 30th and 31st were occupied in sketching the Great Western and Garden Island Falls, stretching in long perspective into the misty distance and broken by the dividing rock and other prominences. Choosing a point opposite the broad face of Three Rill Cliff where. of course, no spray arose, I sat til the east wind drove that of the falls just named upon me and forced me to retreat; for though an artist may work in wet shirt or shoes, he cannot work with wet paper and perhaps, it is well for his health that it should be so. The wet forest however, with its vine-tangled and fern-clad trees, afforded numberless scenes well worthy of a separate study and among them I soon selected one suitable for my purpose; a trunk had fallen down, but had been partially supported by others and before decay had quite destroyed it, some of the younger shoots had struggled up again into the light, and now, increasing into fine young trees had sent down roots, lacing round the old and rotting trunk from a height of twelve or fifteen feet to seek for moisture in the earth.

Friday 1 August 1862

I climbed a tree near the western side in hope of obtaining a general view of the Falls; but could not on account of the dense foliage of others taller and more inaccessible before me. I therefore turned south-east by south, about five hundred yards, toward the angle of the lower river and stationing myself above the deep green tarn formed in its abrupt bens, could see up the stream on my left right into the first bend of the outlet, nearly a mile distant, with the “smoke of the Falls” visible beyond the dense line of forest and about the same distance down it on my right the course of the two portions being straight and parallel, their most distant points forming, from the spot on which I stood, an angle of only twelve degrees. The water is here, as elsewhere, inaccessible, from the height and steepness of the red and yellowish grey precipices that enclose it. The cliff that divides the two portions of the stream must be nearly a mile in length, more than three hundred feet in height and as I subsequently ascertained only one hundred and fifteen yards wide at its base; at its point it seems much narrower and is probably twice as high as it is wide.

I remained until nearly sunset and as in all the views I have taken, found that the magnificence of the principal features so dwarfs everything else, as rocks, trees, etc. which in common subjects would occupy large portions of the picture, that I can hardly bring my pencil to a point fine enough to represent them; still, unless these accessories are minutely and distinctly painted, the vastness of the whole is much invalidated.

I begin to believe that no man but an artist can appreciate these wonderful Falls and not even he til he strives patiently day by day to study and represent them.

One great hinderance when moved from the influence of the spray-cloud, is the annoyance caused to the painter by the incessant persecution of the tsetse. At the moment when one requires the greatest steadiness and delicacy of hand, a dozen of these little pests takes advantage of his stillness and simultaneously plunge their preparatory lancets into the neck, wrists and tenderest parts of the body, one or more cunning fellows actually selecting the places where the lines of fortune radiate or cross with a skill in palmistry that would do honour to an experienced gipsy.

2 August 1862

Moliti, one of the old headmen, brought over a basket of milk for me and I crossed to the eastern side in his canoe. We passed at least three large islands, well wooded, with groves of tall palms towering above the ordinary trees; the glassy surface of the broad river giving back their forms so perfectly that it was hard to tell where reality ended and reflection began. Moshotlani, the petty chief of the ferry and Madzekazi, who had known me in Tete were sitting under the shadow of their principal hut, which in form is cylindric-conical, like those of the Bechuanas, or not much unlike a rifle-bullet set up on end. Fortunately for me, the chief wished me to cut him a jacket, spreading before me for that purpose a length of four cotton handkerchiefs, the price for which they usually sell a slave to the Mambari and consenting to do this I made it the ground of a request that he would give me a canoe to go down to the Falls next day.

Being advised not to tempt the rapids in our present skiff, I landed below the side-creek and walked the rest of the way. The boatman proved rather an expert cicerone; he brought me first to the rocks over which the eastern rapid flows, before allowing me a perspective view from the end of the chasm. About one-fourth of the whole cataract seemed to be on the east side of the outlet and the hollow in which the first bend of the lower river run comes round so close to the face of the cliff that it seemed a wonder another outlet had not broken through, a hundred and fifty yards nearer to the eastern end.

Here the bed of the river seems to have preserved its original height and the water consequently shallower than on the western side is broken into numberless rills, forming falls of various magnitude, some on a grand scale, but the majority mere threads compared with the mighty rapid that forms the Leaping-Water at the other extremity.

The view along the face of the Falls was limited only by the body of vapour filling the chasm and the rocks here, not being drenched with spray, were covered with a drier vegetation among which the scarlet triple spikes and reddish-green leaves of the aloe, springing from the cliffs, or drooping chandelier-like from the black face of the rock, formed an important and interesting feature. The dark-blue hornbills flew among the trees, while little honey birds hovered like brilliant gems over the flowers. The natural inference from this marked difference is that the east wind must prevail during the greater part of the year and that these rocks must be permanently to windward of the spray-cloud. Two or three waterbucks were seen as we returned; but it is a mere chance to hit them as they dart through the thick bush.

We reached the village before sundown and a hut was assigned me with Madzekazi where, while I cut out a pair of trousers for the chief half-a-dozen Makololo who had known me in Tete, gladly busied themselves in making a fire and doing other little offices for me.

4 August 1862

I halted on the bank of the broad blue upper river studded with islands to the very edge of the Falls, with the forest-clad cliffs beyond, and the clouds of smoke rising from the (to us invisible) chasm, wanting only a few ships upon the surface, or batteries upon the islands, to make it the very picture of a naval engagement. While admiring the scene I saw the head of a hippopotamus rising suddenly from the depths of a quiet reach. Now the act of breathing subjects the hippopotamus to a chance of a shot about his ears and so well is he aware of this that unless he feels perfectly secure, he merely snorts loudly in the act of rising, ejects the condensed breath, like the blowing of a porpoise from each nostril and sinks again to his refuge so quickly that the sharpest eye and steadiest hand may fail to strike him. I hit one behind the ear so effectually that my guide at once proposed to ask the chief for a canoe to look for the body in the morning. I wanted to go upon the edge of the chasm opposite the Falls so as to complete my view of the whole front, but he led me by a path past that to the beginning of the long promontory I had sketched the other day as dividing the waters of the Tarn bend. I was now nearly opposite Buffalo point from which I had previously sketched the Falls through the outlet and I found the distance from this bend of the river to the next across that narrow slip of cliff, only one hundred fifteen yards, though its course in the interval must have been a couple of miles. The next promontory seemed even more narrow at its extremity and certainly more picturesque than the first – in fact, if one may compare great things with small, the tall thin cliffs, showing their rich red and yellow tints in the declining sunlight looked rather like profile scenes in a gigantic theatre than real and solid rocks.

5 August 1862

I again shaped my course for the Falls, determined this time to penetrate the dense forest on the southern cliff and stand face to face with the eastern portion of the cataract as I had already done with the western. For two or three hundred yards the ground was dry, the prevalent wind driving the spray from it and the tall aloe-like Moghotse leaf, of which cord is made, reared its thorny points like bayonets, three feet long, set upright in the ground in a most objectionable manner.

The ground sloped suddenly and my guide quietly but decidedly sat down upon the bank. All I could see below was thick dark foliage and blackened trunks, but I tried it and finding a practicable descent called my bushman to follow and proceeded through the now wet and dripping covert along the neck formed by the thickly wooded hollow I had noticed from Buffalo point. The ground became lower and narrower as we advanced, the rank grass concealing the treacherous inequalities of the rocks beneath. At length the forest ceased, the grass covered slopes dipped and contracted suddenly til a narrow wall of black rock, perfect on the side next the Falls, where it still presented a precipice of three hundred feet but broken into rough blocks toward the hollow on the south formed the sole connecting link between the eastern cliffs and the headland of the outlet. Possibly I might have crossed it, but I was already drenched with spray and nothing in the way of art could have been gained by pushing still farther into the cloud. My paper was already soaked and my folio going to pieces, although I held it above my head, face downward during the few minutes I spent in making a hasty outline and my bushmen had already received permission to retire to a drier part. I made another sketch of a portion of the eastern Falls as I returned, but both are very imperfect and the pictures made from them are much indebted to memory.

The old boatman of the rapids, named Zanjueelah, had quite a collection of hippopotamus and other skulls and taking his formidable spear he led us to the narrow skiff, the only one I believe that goes quite to the Falls. He paddled across, that Chapman might take his gun as well as I and we glided swiftly down the river winding as the current swept round the islands or ran in rapids and races over the rocks. In many places the shallows extended nearly across the channel and in shooting through some, although we drew only seven or eight inches of water, we grounded repeatedly, and I caught myself involuntarily saying: “keep her end onto the stream” but old Zanjueela knew the importance of this as well as I and standing in the bows with his pole, while his mate did the same astern, he guided the shallow, narrow craft actually balancing and preserving her equilibrium by the mere pressure of his feet as she rushed down each successive rapid. As we passed the end of one island a hippopotamus, or perhaps more than one, disturbed in some peaceful dream, launched down the bank and plunged into the water just astern. Others appeared in the smooth water on our left where I had fired at them on previous days, but we did not think it advisable to take the old man’s attention from the course of his boat with another rapid immediately ahead and therefore left the sea-cows in peace until our return

The edge of the Falls was now visible, and the sun beginning to decline imbued the eastern cloud of spray with the prismatic colours, not in a complete bow, but in a segment so short as to show no visible curve and so broad as to leave no portion of the cloud untinted by its delicately brilliant hues which sometimes when jets of vapour leaving large intervals between shoot upwards through the arch assume the appearance of lambent, flickering fire. About ninety yards from the edge of the cataract our course was suddenly and skilfully changed and we shot into smooth water on the eastern side of Garden Island, where sticking the boat ashore without fastening of any kind we walked over rocks bare up to the high-water line and through the tangled little forest to the Doctor’s garden. We found that a hippopotamus had recently entered the enclosure and could not recognize any plants among the rank vegetation which the moisture had caused to spring up.

There was only one good view from the island – that toward the east, but it was magnificent; the central portion of the perpendicular cliff projects so as to form the narrowest portion of the fissure, which is here about seventy-five yards in breadth, but the eastern side slopes suddenly away, so as to increase the breadth to one hundred thirty to one hundred forty and to throw backward those falls that are nearest to the eye and allow those beyond them to be seen in beautiful perspective to the eastern extremity of the chasm.

The front of the cliff slopes down so as to be somewhat lower, but a mere trifle in comparison with the vast depth still below it and here one may stand on the very edge as on a pier of solid masonry and look not only into the dim intricacies of the mist-hidden distances – spanned over by a rainbow, glorious in its brilliant loveliness and forming, but for the small segment cut out by the shadow of the rock he stands on, a perfect circle, surrounded by another with reversed colours, fainter and more indefinite as it approaches the thinner spaces in the mist; - but he may peer down into the very abyss beneath him, see his own shadow on the troubled eddying waters four hundred feet below and speculate, if he so pleases, whether geological ages were required to accumulate the heap of debris which has fallen from the receding portion of the cliff; or whether as we think, the mass crumbled down at once in the convulsion of nature which formed the chasm.

Requesting his friend to measure angles and such-like tedious but necessary details, the artist endeavours however humbly and imperfectly to reproduce the glorious scene. It is in vain. Hardly has half an outline been completed when the prudent Charon of the rapids warns him again and again that paddling up the stream is a long work and that it is not a road for men to travel in the dark. Reluctantly he closes his work and obeys the summons.

The water is baled from our somewhat leaky little skiff and now comes the struggle up the rushing waters in which perhaps a man who to some extent knows and can appreciate the nature of the various dangers feels more when reduced to sit as a helpless, useless passenger than one who is totally inexperienced. But he too can understand and glory in the skill and courage of the veteran who commands the boat. See him now, standing erect and fearless in the narrow bow, as the water dances round her, observe how firmly, yet with what rapidity, he poles her against the current in the shallows; how quickly he catches up his paddle in deeper water; how carefully he guides her across the smoother parts his unerring eye watching, before he enters them, the curls of the various eddies; and with what judgement he shoots end on, into the exact place where it is just possible for her to ascend the successive rapids, jumping out at the proper moment to force her up the steep incline and in again as soon as she is in the level waters.

And now, nearly half a mile of distance from the verge has placed us in comparative safety and the hippopotami are appearing in the still water near the rocks above us. He shears his boat so as to give us a chance, but the wary animals snort and dive too quickly. He runs her higher up into the shallows and landing there – if standing mid-leg deep on a submerged rock may be so called – we wait their re-appearance. My bullet strikes the water close by the head of the first and enters between eye and ear; while Chapman’s, just grazing and raising a jet of spray so close by the next that one would think it impossible to miss, goes ricocheting away over the surface til it passes the edge of the Falls and loses itself in the chasm.

The remainder of the passage is long and tedious, but both danger and difficulty diminish as we advance and before sunset we are at our bivouac, where promising Zanjueelah an adequate reward, we enter into a conditional arrangement to be taken tomorrow to an island where the hippopotami are likely to come ashore at night.

During our stay here, at every possible opportunity we had taken measurements and observations for determining the geographical features of the Fall. We commenced by measuring a base-line at the western end of the chasm and triangulating with sextant and compass as far into the spray-cloud as we could without losing sight of our landmarks. The rest was measured on independent base-lines or estimated by firing rifle-bullets with the sights elevated for the necessary range, or when that was impracticable by careful pacing. We had no line long enough for actual sounding and it was difficult to take angles with great accuracy for want of sufficiently definite points at top and bottom.

But comparing our estimate with the depth obtained by Livingstone, i.e. three hundred and ten feet when his line rested on a heap of rocks and did not reach the bottom, we thought three hundred and fifty feet a tolerable approximation, but that of course will give way to Sir R. Glyn’s measured depth of more than four hundred feet; its length is from eighteen hundred to two thousand yards, its breadth opposite Garden Island, the narrowest point, seventy yards and in the widest from one hundred to one hundred thirty yards. The fissure by which the lower river escapes seems nearly three-fourths of the distance from the western end and the width between the enclosing precipices cannot be more than eighty yards. The river must be much narrower, but in no place is it possible, as far as we know, to descend to the water.

About one hundred fifty yards to the south of the outlet it turns suddenly to the right makes a straight course to five hundred or seven hundred yards south-east from the western end of the Falls, then doubles back on itself, so that the two parts of the stream separated only by the Tarn promontory – a cliff one mile long, more than three hundred feet high and only one hundred fifteen yards wide at its base; the next turn rounds the thin wedge-shaped promontory of the Profile cliffs and turning again to the south-east it receives a small tributary, the Masoe which in wet seasons must form a beautiful cascade and continues its course til it is lost to sight among the hills.

The difference in the appearance of the country is most marked and striking. The broad river above the Falls is bordered by palms and luxuriant tropical vegetation, while along the lower river, deep sunk in its narrow chasm, the country is dry and arid except where fields of maize or millet are cultivated along the tributary streams or when in the rainy season its barrenness is changed to fertility and verdure.

To venture an opinion on the geology of this cleft would be beyond the province of an artist, but the impression on our minds was that nothing but volcanic agency could have produced it. The edges are sharp and well-defined, the opposite sides correspond so as to suggest the idea of parts broken from each other and all the rocks we find upon the surface seem igneous.

During our return journey through Namaqua land I was much struck with the wild disruption and upheaval of the strata and I was informed that at the mission-station of Beersheba, the cattle graze on a large plain in an extinct crater. Slight earthquakes are by no means uncommon and we experienced several shocks during a few months residence at Otjimbengue.

We were unable to trace the intermediate course of the river, being obliged to re-join our wagons and take them from Daka [Deka] to Boana between the Matietse [Matetsi] and Luisa rivers; whence I started afoot with a troop of Damaras and hired Makalakas carrying tools, etc. for the rebuilding of the deficient portions of the boat near the island of Molomo-ea-tolo (mouth of a koodoo) in the junction of the Luisa river, sixty or seventy miles in a direct line from the Falls, but more than double that by the road we had to travel.

I cleared and built my house on a small limestone elevation, 200 feet in height, in latitude 18°4´56" and naming it Logier Hill after my much esteemed friend in Cape Town, commenced cutting trees, sawing them into planks and building midships to the copper bows and sterns. Chapman soon joined me and after a trip down the river to Sinamane’s to ascertain that there was no insurmountable impediment to navigation, he formed a hunting camp between my station and the wagons, to supply meat to both. The various inevitable difficulties we combated and overcame as they arose and had every hope of having our boat ready to descend the river with the coming flood when the difficulty of procuring food, owing to the migration of the wild animals to the rain pools now filling in the desert reducing me for ten days to a diet of buffalo hide and water and the prostration of all the native servants, as well as my fellow-traveller himself, by fever, obliged me to abandon my work and return to him, that we might save the lives of the people by bringing them from the unhealthy swamps of the Zambesi to the purer air of the elevated desert. Our exhausted resources, the death of some of our followers by illness and the murder of others by a marauding party of Matabili, prevented our renewing the journey; but we believe nevertheless, that with more adequate supplies it is quite possible to carry out the plan that has now been temporarily frustrated and only hope that before long we may again be in a condition to attempt it.

References

T. Baines. The Victoria Falls Zambesi River, sketched on the spot by Thomas Baines, F.R.G.S. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1969

T. Baines. Explorations in South-West Africa: being an account of a journey in the years 1861 and 1862 from Walvisch Bay, on the Western Coast to Lake Ngami and the Victoria Falls. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts and Green, London, 1864

When to visit:

Anytime

Fee:

Entrance fee for visitors to the Victoria Falls

Category:

Province: