Home >

Matabeleland North >

Three oral history statements made in 1937 by amaNdebele warriors present at the killing of Allan Wilson and thirty-three other Europeans on 4 December 1893 at the Shangani River

Three oral history statements made in 1937 by amaNdebele warriors present at the killing of Allan Wilson and thirty-three other Europeans on 4 December 1893 at the Shangani River

National Monument No.:

13

How to get here:

GPS Location: 18°46´05"S 28°07´33"E

Three oral history statements were made in 1937 by amaNdebele warriors present at the killing of Allan Wilson and thirty-three other Europeans on 4 December 1893 at the Shangani River to Foster Windram, then a young journalist at the Bulawayo Chronicle. They were:

- Siatcha [S] son of Matilingwane, at Phillips Farm, Bubi District on 20 November 1937; also present were his wife Stambe, a daughter of Lobengula and Lubane, son of Mkubani, and Peter Kumalo as interpreter.

- Ginyalitsha [G] son of Sigojwana and grandson of Ngoka, at his kraal off the Queens Road, on 23 November 1937; with Peter Kumalo as interpreter.

- Ntabeni Kumalo [N] son of Mhwebi, who was a son of Mzilikazi on J.P. Richardson’s farm, Esigodini on 25 November 1937; with J.P. Richardson as interpreter

Introduction

Those not familiar with the story of thirty-four young European men who were trapped on the northern side of the Shangani River and the unknown number of amaNdebele warriors[1] who also died in the Mopani forest in the far northern part Matabeleland on Monday 4 December 1893 should read Shangani Patrol on Wikipedia, or A Time to Die by Robert Cary, or Pursuit of the King by John O’Reilly.

The purpose of Shangani Patrol was to carry out a reconnaissance preparatory to capturing King Lobengula; Allan Wilson had crossed the Shangani River in the late afternoon and followed the King’s wagon tracks for 9 – 10 kilometres and came upon his two wagons. But the King was not present, and Wilson made the decision to wait in the bush for dawn next day in the hope that reinforcements would arrive, and the King might then be captured. Lobengula however, had abandoned his wagons and left the area on horseback. Many accounts have been written about the final engagement, but the few surviving members of the original patrol including Sergeant-Major Judge and Corporal Ebbage and the American Scouts Frederick Russell Burnham, Pete ‘Pearl’ Ingram and Australian Trooper William Gooding were not present at the last stand; so, for the only really accurate accounts we must use the following oral histories below.

1896 Painting belonging to the Bulawayo City Council by Allan Stewart depicting the last stand of the Shangani Patrol

[G] When Lobengula heard the white people had crossed the Shangani River,[2] this side of Gwelo[3] on the Salisbury[4] road and were coming to Bembesi, he said: “I had better move now.” The Imbizo[5] had not left yet. Then Lobengula left Bulawayo and went and stopped near Umguza[6] between Konce[7] and Umguza where the two rivers joined. The Imbizo followed and found him there and Lobengula said: “I want to go with you, so that with the white people coming from two sides, the one from Salisbury[8] and the one from the Matoppo line[9] and they meet in Bulawayo, they won’t find me there. But they will follow me. Then if they follow me I will tell you to fight them.” The Imbizo refused and said: “We don’t want you to run away before we die. We want you to stay here until all of us die.” Lobengula refused and said: “I can’t wait. I wanted you to go with me so that you will see where I am going.” But they refused. Then Lobengula said: “You have disobeyed my order: now you can go and fight on your own hand, but I will tell you this, that if you see the white people have already made their camp, you must not fight. You must leave them until they pass Ntabazinduna, and until they get to Umguza and those that have horses, let them cross the river, and those that follow with the wagons, before they cross, then you will attack the wagons. Then you will divide them in two.”[10]

[N] …and he sent the Imbizo scouting and told them to climb up Ntabazinduna[11] and they would see their dust from there. But he told them not to attack them. He said:” Let them come down as far as the Umguza (where the railway crosses it at the Old Fountain Hotel) and there I will attack them. If you find them in laager you are not to attack them on any account. You must wait until they are trekking down to the Umguza and attack them when you see the wagons on the move.”

The Imbizo did not carry out these orders. When they saw the white people, they were in laager at Egodade (Bembesi) and instead of following out the King’s orders, Mshani said: “these are the wagons of the King; go and take them.”

So, they attacked and were defeated, and many were killed. I was there among them and they scattered us. We never even got to the laager. We had never before come into contact with the wonderful gun with which they killed – the sigwagwa.[12] When the sigwagwa opened fire they killed such a lot of us that we were taken by surprise. The wounded and the dead lay in heaps. While the sigwagwa was going they were shooting with rifles too.

When the survivors came to report to Lobengula at Umgusa he said: “I know, I heard the firing. You did a very bad thing not to follow out my instructions and attack while they were on the move. You ought to have known that it was very dangerous to attack the laager.”

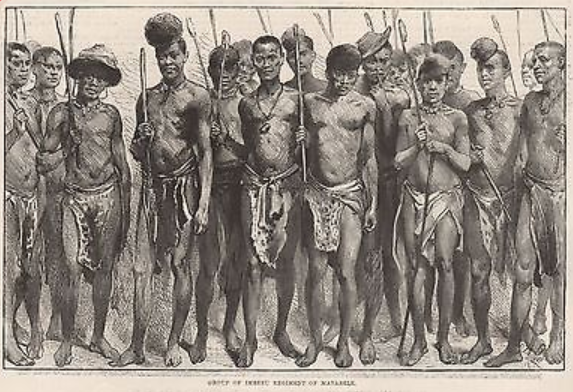

Imbizo warriors from The Graphic 1893

[S] Then the white people fought the Imbizo at Egodade (Bembesi) in the Thabas Induna reserve and defeated them. The other impi came to report about the death of Umgandan,[13] and when the Imbizo left Bulawayo to fight at Egodade, Lobengula left Bulawayo too and went straight to Shangani. And he stayed on Shangani River on this side, the Bulawayo side, and waited for the Imbizo to follow him.

The first to fight with the white people were the Insukamini.[14] When the Imbizo went out, Lobengula advised them not to fight the white people at Egodade but the Imbizo said: “No, you are a coward. We will go and finish off those white people, and then we will come back and plough.” It was just before the ploughing season. Lobengula told them: “No, the best thing is for you to come with me, then you will fight them when they find me.” But they would not listen. They said: “No, you are a coward.”

[N] Then Lobengula’s wagons were inspanned and they set out for the Shangani. They did not stay on the road[15] except to outspan for the night. Some of the Queens came with Lobengula. He took those that were nearest when he left Bulawayo. They made their first outspan at Shiloh, where Thomas[16] used to be and the next camp was at Bembesi. They came to a stop on the other side of the Shangani River and they were there two days.[17]

[S] So Lobengula said; “All right you go” and he left and went straight to Shangani. He expected them to follow him and come and report. Lobengula stayed one month at Shangani. Then the impi arrived and they reported those who were dead. Then Lobengula sent Sirulurulu and Bejani[18] with some money[19] to go and give those white people and told them to tell them they must stop fighting; Lobengula wanted to pay tax now. At Ngwamba they met two people – the white impi were following up and these two were in front.[20] They spoke to them and gave them the money. One had a white horse and one a red horse and then they went back.

[G] …Lobengula had all his people with him. Those who had fought with the white people and escaped had come to him. While at Shangani some of them crossed the river with Lobengula and some remained this side [i.e. on the south bank of the Shangani River] Lobengula was in his wagon. Then Lobengula saw that now he was powerless; and he sent Bejani and Sirulurulu with money in bags on horses and said: “Take this money and give it to the white people. Tell them I have paid now, they must now go back. I don’t want to fight. If they still come on, you must fight.”

[G] On their way these people met two white people and gave them the money.[21] The white people asked them: “where are you going?” So, they gave them the message and they said: “Didn’t you meet another impi of white people following Lobengula?” They said they hadn’t met them. So, these white people said: “All right, give us the money; we will take it to the white people” but the impi had gone.[22]

[S] When they were at Shangani they heard that the white people were still following them and were now arrived at Ngwamba. The Lobengula called all the impis and told them: “All right, you go there now and meet these people.”

[S] They found them at Lupani.[23] The white people were having lunch and the horses were grazing near the river. The impi saw them sitting there and they were still watching the white people eating. Then the Matabele divided into two sections; some of them went to the right and some to the left because Lobengula told the people: “Those white people are still following me, although I have given them money. If you find them in an open place, you must not fight them, you must wait until they get into thick bush.”

[S] After the Matabele had divided into two sections, the white people got ready and mounted their horses, and about thirty of them[24] with horses went off following the trail of Lobengula, expecting they would find Lobengula at Shangani, but Lobengula had already left early that morning. They arrived at the Shangani River, where Lobengula had been on the Bulawayo side of Shangani and found that he had gone. Then they followed the spoor of Lobengula’s wagon across the river. The impi on the right hand found that this party of white people had already passed them, so they followed them. The Matabele were hiding all this time, and they did not actually see the white people leave the camp. They only saw the spoor of their horses.

[S] Then the impi that was on the right hand followed the white men on horses and the impi that that was on the left hand went to look at the camp again and saw that the rest of the white people, with the Maxim guns, had also left.

[S] The party of thirty on horseback crossed the river and found an impi there, the Ubabambeni,[25] at a place called Epupu. There they found Lobengula’s wagon. Lobengula had left his wagon and taken to a horse and had taken his children; Mpeseni, Ngubowenja[26], Njube, Chakalisa and Nyamande.[27] When the white people got there, they said to the Ubabambeni: “Hikona Dubula, Ubabambeni.” Then the Ubabambeni didn’t shoot.

[N] …Lobengula left his wagons and went off on horseback on the day the fight took place. When Alan Wilson’s party arrived, Lobengula had already left. The indunas said: “it is raining now, and they will be able to follow your spoor very easily. Take your horses and go.” I cannot say how many people went with him. Lobengula left in the afternoon before Wilson’s party came to the wagon. Wilson’s party arrived at sunset. They said: “Sakabona Lobengula, Sakabona Lobengula” and called: “Bayete Kumalo, Bayete Kumalo.” Lobengula had already left. The white people went to the wagon and found that he was not inside and took some cartridges.[28] Then they went back and camped.

[G] …They nearly got Lobengula. There was a man who was captured by the white people who released him telling him he had better go back to his people and not come anymore, saying: “you can go and stay now. The matter is finished now; we only want Lobengula now.” And that man turned around the other way and ran fast and found Magwegwe[29] and told him and warned him.

[G] Then Lobengula left his ox wagon and took to horses and left the Ubabambeni, the Ingwegwe – two regiments, behind. Lobengula left with Magwegwe and told the two regiments he left behind: “that if the white people come to this spot I will know because I will hear the fighting. You must start to fire as soon as they come so that I will know they are here.”

[G] When the Europeans arrived the Ubabambeni did not fire because the Europeans shouted: “Hikona Dubula, Ubabambeni.” The Europeans had many Matabele deserters with them. The sun was about setting, then it started to rain. When the Europeans got to the wagon they shouted: “Sakabona Lobengula! Sakabona Lobengula!” But when they lifted the flap of the wagon tent they saw there was nobody inside. Then they turned and saw the people scattering and they knew Lobengula was not far and they wanted to look around for the spoor of the horses and it started to rain. Then they went to pitch their camp some distance away and made no fire, thinking Lobengula would come back during the night.[30] In the meantime, it was raining heavily…before sunrise, while it was still dark, the Europeans came back and surrounded the camp and again cried: “Sakabona Lobengula.”[31] Some of them got inside the wagon and they found no one. They found some ammunition in the wagon and took it away.

[S] When the white people got to the wagon[32] they started a search for Lobengula and they got hold of a man, Silawulane, and they left the wagon and stopped about 50 yards away, expecting that Lobengula would come back at night. They took Silawulane with them. Then the white impi that was following with the Maxims stopped on the other side of the river, because it was dark, and the Matabele impi that was on the left side slept on the same side of the river as the white people. At about midnight the rain started. It was a heavy rain, and the Shangani River came down in flood, and the white impi with the Maxims could not cross the river.

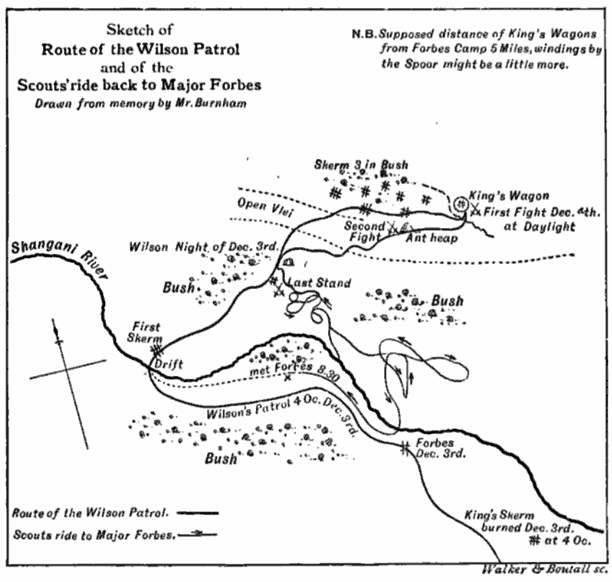

This hand sketch was drawn by Frank Burnham

[N] Early next morning they came back to look again at daybreak. I was not actually there myself, but the story that they told me was that Mshani [Mjaan] shouted to them all: “I know the white men; I was captured by them at Mkwahla, and I know that they will be here very early in the morning, so get up and get ready.” He had hardly said this when Wilson’s party arrived. But they did not get up to the wagon this time.

[S] Then the impi that had followed the white party on horseback started to fight with them. I was there myself. The first Matabele who fought were those who had followed the party on horseback. The people who had the Maxims on the other side heard the guns and woke up.

[N] The white people shouted out to them: “don’t shoot; we are not shooting.” With that the Matabele started firing. The white people fired a few shots back and turned and followed their track back and met the other impi which was following up Lobengula. When these Matabele heard the firing, they got on both sides of the road and waited in ambush. In the meantime, the first lot were following, so they surrounded the white people on all sides.”

[G] So the Bulawayo and the Inyati regiments came up and attacked the white people when they saw them in that camp. There were only thirty white people. The white people killed many natives and when the white people wanted to go back to the rest of their impi, then they met the Matabele who had remained behind. The impi saw the white people coming and the white people saw them and dismounted from their horses and started defending themselves. The Matabele surrounded them…

[S] The Matabele attacked Wilson’s party. Then the Matabele on the other side of the river heard the guns and came to the river and found the white people waiting by the river because they could not cross, the river was full. On their way they met a woman who had been caught by the white people. She warned them and said: “Wait, wait, there are white people just near here.”

[S] The white people were too busy watching the river to notice them, and so they crept up behind them and shot at them.[33] These two bodies on the south side of the river then engaged. Meanwhile Wilson’s party was fighting on the other side. The attack on Wilson’s party started before sunrise and lasted until about 11am in the morning.

[S] Wilson’s party sent Johan and another man to fetch the Maxim’s.[34] They didn’t know the river was full. When they got there, they found that the river was full. Johan and the other man did not cross the river, but they did not go back.

[G] After a long time the noise of firing was heard on the other side of the river – Maxims and the inganunu, nine pounder.[35] The Matabele who were attacking Wilson’s party scattered when they heard the fighting and the white men attempted to mount their horses. The someone shouted: “No, that is the Ishlati and Isiziba who are fighting the white people on the other side of the river,” so the impi returned to the attack.

[G] It is not true that the battle was over by 10am; the fight lasted a long time. I am not quite certain because at that time we did not know about time, but I should say it lasted until about 1pm or 2pm, because the white people did everything to defend themselves. They even pulled the horses together and took cover behind them when the horses were killed, until their ammunition gave out. When the Matabele got them, they were using their pistols.

[N] I was present at this fight. The white people dismounted and stood back to back in groups. When all the horses were shot they took shelter behind them. There was one of the white men who never took shelter. He stood there all the time with a little stick in his hand. All the others were dead, and we thought that he ought to be taken prisoner, but a young majaha could not resist the temptation and shot him. They stayed in the same place all the time. They remained where their horses were shot. They did not make for a little knoll. There were forty men; the man with the stick was the man who was killed last.

[G] Before they finished their ammunition a man who spoke Zulu among them said; “Leave us now Matabele, Hikona qeda zonke, Matabele, we have seen that you are good fighters. We will go back to Bulawayo and tell our people that we have fought with you for a long time.” The impi did not agree with that. They said: “you kept following us from Bulawayo, you had better finish us all.” The Matabele were just close by, they were closing in on them then. When the white people saw the Matabele would not listen, all of them took their hats off their heads and sang and then shouted: “Hip hip hooray” and then they said no more and fought to the end. I am not certain, but from what I know now I think they sang God Save the Queen.[36] The fight was a long one, we worked like the devil and the people who had died in the morning had already blown up in the hot sun by the time the battle was over.[37]

[G] When they finished the white people there, they wanted to go and help the others on the other side, but they heard no more firing and they met those people coming. The river was down then.[38] I was at Shangani. I was among those who were on the other side – Wilson’s side – and I was among those who attacked Wilson’s party.

[S] I was fighting against Wilson’s party. Some of the white people, when there were just a few of them left said: “Hikona qeda zonke, Matabele” (Don’t finish us all) I was there, and I heard that. The Matabele had only a few guns. When the white people were nearly finished, and their ammunition was finished, they started to pray. They were standing. They did not sing. They stood up and covered their eyes with their hands. It was shortly after sunrise that the white people moved from the place where they were attacked to a piece of high ground.

[S] Many Matabele were killed by Wilson’s party before they were wiped out. Some of the Matabele had guns and it was with guns that they killed the white people. Only one white man was killed with assegais. I can’t tell if he was the Induna; but he was the last one of all that was killed. He had a pistol in his hand when he was killed, but I think all the ammunition was finished. They all had pistols. The Matabele killed them with their guns and when they rushed in to finish them off there was only one left. The Matabele rushed in shouting their war cry “jhee.” To say “jhee” means: “we have finished them all.”

[S] When the white people’s ammunition was finished they stood up and covered their faces with their hands and prayed. The Matabele were still shooting at them and shortly after we rushed in and killed the last man.

[S] I was tired with fighting and the noise of the guns, so I cannot say for certain that they did not sing. There was a quarrel afterwards between two of the Matabele as to which one had killed the last of the white men. Their names were Jamela and Mdilizelwa.

[G] …I cannot tell how many were left when they were finished because after they cheered they took cover again. When the impi noticed the shooting was less and they saw the ammunition was finished, they rushed. Some of the white people shot themselves with their revolvers. One white man shot one of the Matabele in the mouth with his revolver, as the Matabele came shouting with his mouth open and assegai raised. If there had been fifty of them, they would not have been beaten.

[G] I did not see it myself because the impi was big and those at the back could not see what happened in front, but some of the Matabele said that one white man was left fighting alone. Some of the people in front said that when they were just about to kill the white men with assegais they shot themselves. The Matabele said: “Madoda; how is it that we fought with thirty people the whole day long and if their ammunition had not given out we would not have beaten them; our people are finished.” Even to this day those who were present at Shangani still talk of it. The Matabele said: “They are Amadoda which means they were men. The man in charge of them was very clever and very brave.”

[S] Lobengula was gone. He went a long distance before he died. Lobengula died because he got very angry with the white people, because he paid them, and they were still following him. It is not true that he died of smallpox. The true story was that his heart was broken, I cannot say whether he killed himself.[39] I don’t remember anybody who is still alive who can tell what happened to Lobengula. Some of the Queens, but not all, were with Lobengula when he died, some were in Bulawayo. When Lobengula died, Magwegwe, one of his chief councillors, was with him, also Sivalo, Sirulurulu, Ndonsa, Mlangeni and Mpanda. Magwegwe died on the same day as Lobengula; he died of the same cause. The people with Lobengula did not have smallpox.

It was the people who went to the Zambezi, the Ihlati and Icapa, who had smallpox. When the impi went to Victoria, another impi went to the Zambezi – a big impi, and they brought back the smallpox and many of them died. They were raiding on the Zambezi to get cattle. Some of the Matabele were vaccinated by a Makalanga[40] named Sotshangaan. Our vaccination was different from yours, when a man had smallpox we used to take some of the matter out of the bad part and cut the arm of another man and rub a little in. We asked the people of the Zambezi, the Batonka[41], what to do about the smallpox and they told us about this, we also heard about it in Zululand. When we did this, the person would not get smallpox, he would only get a swollen arm. We did not do this to people who already had smallpox.

[G] I know nothing of the death of Lobengula because he trusted nobody when he disappeared. He trusted no one because some of the Matabele were already with the white people and he was afraid they would give him away. When the impi went to report to him he had disappeared, and they don’t know what happened to him. No one knows what happened to him after the Wilson fight. They sent scouts to look out for him, but they didn’t find him. When he left he sent the people back and told them not to follow him anymore. Magwegwe went with him. I think Magwegwe died first.[42] Magwegwe’s body was found and the people buried him.

It is quite true that Lobengula said: “O umkumbula O Lotje” I am now thinking of Lotje:[43] because Lotje told him not to fight with the white people. But that was on the way to Shangani before the fight took place. Lobengula also said: “Umbigo told the people that Nkuluman was alive and the people misled me and told me Nkuluman was dead. Now these people have run away from me.” He was talking to the impi. “All my property will be taken by the white people. You can take my cattle back, but you won’t have them. The white people will have them all.”

And he said: “You said I used to kill people, and yet I didn’t kill anybody. You were the ones who were killing people. Now you see the white people are coming here, you are all pleased.” He was referring to those who had deserted. Nobody replied to that, they all kept quiet. And Lobengula said: “The white people are coming now. I didn’t want to fight with them. I want you to take a stone and put it on my head bekalitje kanda – and tell them I no longer want to be King. It is finished today.” Bekalitje kanda meant this was the end of Lobengula as King. The people were still arriving, and the white people were very near. This happened after they crossed the Shangani River.

[N] I was not there when Lobengula spoke to his people. His last words to his people were: “you have said that it is me that is killing you; now here are your masters coming. You disobeyed my orders and now you have put me in this bad fix. (Ning enza ulunya) You want me to be caught by the white men, but the white men will never catch me. I will throw myself over a height (ngezaziwisela eliweni) Now you will find what real trouble is. You will have to pull and shove wagons; but under me you never did this kind of thing.” These were his last words. He also said: “Umkumbula Lotje.”

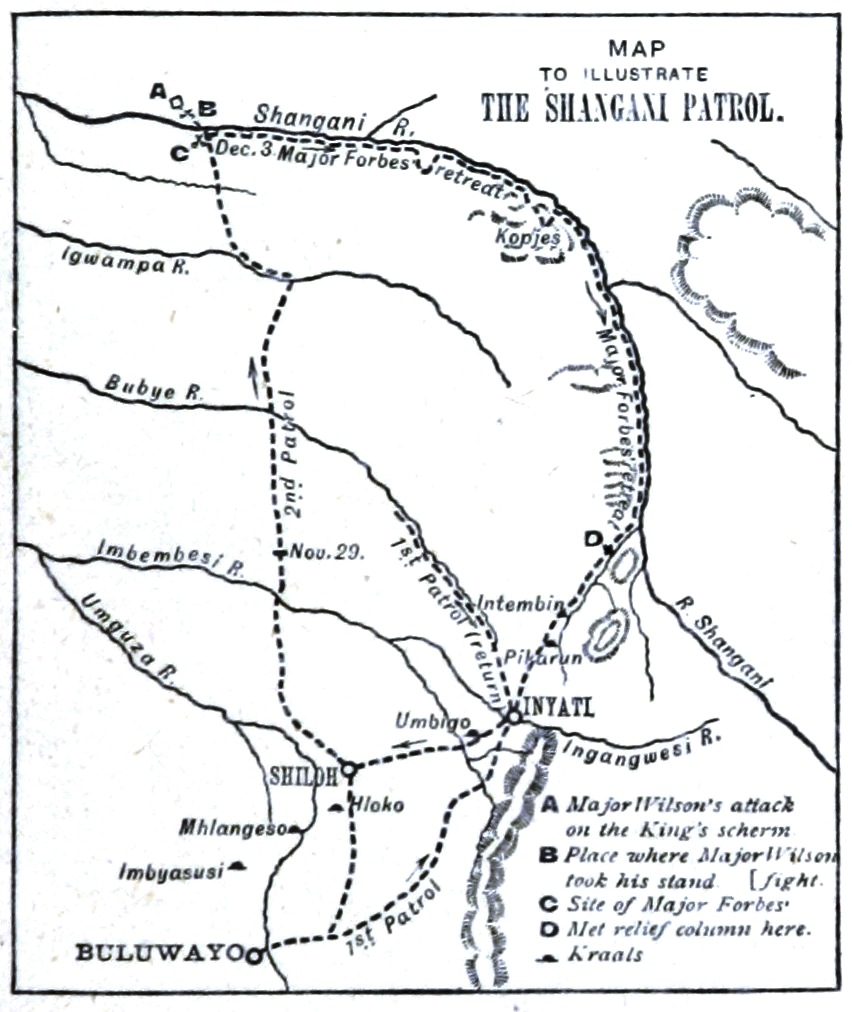

This map from Wikimedia Commons was originally from: The Wars of the Nineties. A History of Warfare of the last ten years of the Nineteenth Century by A.H. Atteridge

Forbes’ column left Shiloh on 25 November but two days later Forbes decided their progress was too slow and the force was reduced to 158: 96 returning to Bulawayo with the wagons and they reached the Shangani River on 3 December. Following the loss of the Shangani Patrol on 4 December (see Burnham’s hand drawn sketch map above) Forbes column retreated down the Shangani River being harassed by the amaNdebele until on 14 December they met Selous and Acutt, scouting ahead of a relief force camped on the banks of the Longwe River, a Shangani tributary, before reaching Inyati Mission the next day.

This final account is an interview with M’Kotchwana, an amaNdebele warrior who fought at Shangani and was recorded by a reporter of the Matabele Times and published by the Sydney Mail on 23 July 1898

When the white inkosi[44] Wilson came across the big river Shangani, we watched him, and although he did not know it, he was surrounded on all sides by the remnants of regiments which had fought at Bembesi, the Imbizo and Insukamini, the Nyamandhlovu and others. At night fall we missed the white amakiwa,[45] but toward the rising of the sun, Mjaan, the great Chief, came to us and said: “I have heard the white warriors in the bush, come, let us go and kill them.” We were about one thousand in number, and without noise we went and surrounded the place where the white men had their fire. Two of them were standing up looking into the bush. Some of us made a little noise. One of the white men standing awake went and woke up another man. I think it was their inkosi. He came and looked all around into the bush and then aroused all the other amakiwa. They got up, and I saw they were getting their ammunition ready and saddling their horses. As it drew near for the sun to peep over the edge of the world, we started firing at the white men. They mounted their horses and tried to proceed in the direction of the great Shangani. But our men shot well, and horses dropped dead. It was a cloudy morning and the rain fell fine and swiftly. There were as many amakiwa as three times the fingers on my two hands. Most of them had black covers[46] on their shoulders.

When the white warriors found they could not go on, they shot the living horses and stood behind them waiting for us. We fired our guns at the white men, but at first, they did not do us much harm, as we were well-protected by the trees and bushes. As the sun rose we noticed several of the white warriors lying dead. Mjaan gave orders to rush up to the enemy. We issued from behind the protecting trees and tried to run up to kill Wilson and his party, but they killed many of us with the little guns in their hands and wounded more.

“How many were killed in that first rush, M’Kotchwana? As many as six times the fingers of my two hands – so many,” and the old warrior waved his hands six times.

“But how many were killed outright? So many,” and M’Kotchwana signified forty. Then we went back behind the trees and fired often, until many of the amakiwa fell and few remained. Again, Mjaan said; “let us kill all that are left” but some of them said: “No, they are brave warriors, let us leave the life in those who are not yet dead.” But the men of the Imbizo said: “No, let us kill all the white men.”

Again, we rushed against the few that remained standing. When they saw us coming they made a big singing noise, and then shouted three times. They killed more of us. I was struck near the temple and remembered no more. My brother told me afterward that all the white men fell fighting until the end. They were brave men, my father. The next day at sunrise we took all their clothes and skinned the face of the biggest white amakiwa and took it to Lobengula, who was away one day’s journey. The Great Chief said that was not the skin of the leader. We returned and took yet another skin off the face of a white chief. When Lobengula saw it, he was satisfied. He asked whether his Imbizo regiment had done all the killing. When he heard that they had not done more than others, he said: “have I then all this time put my trust in a lump of dirt?”

I had two sons killed that day, my father, said M’Kotchwana and my brother was shot in the stomach. The amakiwa were brave men; they were warriors.

References

The above oral statements were taken by Foster Windram, with the help of Peter Kumalo, when he was a journalist at the Bulawayo Chronicle in 1937 with those persons in their home kraals who had personal knowledge of the events that had taken place; there are copies at The National Archives of Zimbabwe (CR 2/1/1) / Bulawayo Library and with Alan Windram.

F.R. Burnham. Scouting on Two Continents. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1975

R. Cary. A Time to Die. Howard Timmins, Cape Town 1969

D. Grant. The Shangani Story. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 13, 1994 P.81-96

D. Grant. Focus on aspects of the last stand of the Wilson Patrol and its aftermath. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 13, 1994 P.97-100

R. Marston. Own Goals, National Pride and Defeat in War; the Rhodesian experience. Paragon Publishing, Rothersthorpe 2009.

J. O’Reilly. Pursuit of the King. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1970

T.M. Thomas. Eleven Years in Central South Africa. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1970

W.A. Wills and L.T. Collingridge. The Downfall of Lobengula. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1971

Wikipedia.org/wiki/Shangani_Patrol

Notes to text

[1] Mjaan or Mtshana, the amaNdebele commander and izinduna estimated five hundred casualties.

[2] This was comprised of Major Patrick Forbes Salisbury Horse column of 258 men, 18 ox-wagons, 2 Maxims and 2 artillery pieces and Major Allan Wilson’s Victoria column of 414 men, 18 ox-wagons, 3 Maxims and 2 artillery pieces. From Tuli Commandant Pieter Raaff led 225 men of Raaff’s Rangers.

[3] Now Gweru

[4] Now Harare

[5] Original was Imbezu, I have used the modern form of Imbizo

[6] Now Mguza River

[7] Now Gwayi River

[8] The Salisbury column under Major Patrick Forbes and the Fort Victoria column under Major Allan Wilson had joined at Iron Mine Hill on 16 October 1893

[9] A third column under Lt-Col Goold-Adams, the southern column which left Tati on 19 October 1893.

[10] Lobengula’s instructions were ignored. At the battle of Shangani (Bonko) the attack was at dawn and at the battle of Bembesi (Egodade) the attack was at midday, on both occasions the columns were in laager and protected by Maxim guns and artillery. See articles on both battles in Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[11] A prominent hill thirty kilometres to the northeast of modern Bulawayo

[12] The Maxim gun (called the ‘Sigwagwa’ by the amaNdebele) was first used in a live fire role at the battle of Shangani (Bonko) on 25 October 1893 when the Insukamini, Ihlati, Amaveni and Siseba regiments attacked the laager of the combined columns and lost an estimated fifteen hundred warriors. The Imbizo who had scornfully mocked those who fled at Bonko suffered the greatest casualties a week later at the battle of Bembesi (Egodade)

[13] This refers to the Victoria incident of 18 July 1893 which was the culmination of a tide of events. On the one hand the Europeans under the leadership of Jameson who was telling Rutherford Harris; “There is no threat to the whites but unless some shooting is done I think it will be difficult to get labour even after they have all gone. There have been so many cases of Mashona labourers killed in the presence of their white masters that the natives will not have confidence in the protection of whites, unless we actually drive the Matabele out.” On the other hand, Umgandan the young amaNdebele Induna bluntly told Jameson: “Mashonaland is ours, we conquered it, and have every right to be here. We have not molested any white man, but as for the Mashonas, we have been sent by our King to accomplish certain duties and we will remain until those duties are done.” [R. Marston P54-55] Captain Lendy was sent out after the meeting with a thirty-eight-man mounted patrol. The Newton Report written after the incident, for which almost all the participants were interviewed, found that Lendy’s troop fired first, that the amaNdebele were leaving the area but had burnt down several kraals and that they offered no resistance. About nine amaNdebele were killed by the troop, including Umgandan, another fourteen were killed by vengeful Shona.” [R. Marston P57]

[14] Original spelling was Insugamini, thereafter I have used the modern form of Insukamini

[15] Ntabeni Kumalo does not literally mean a road; clearly there were none in the trackless mopani forests that stretched north towards the Zambesi River.

[16] Reverend Thomas Morgan Thomas (1828 – 1884) Born in Wales in a poor family, he started work at the age of seven and became proficient in blacksmithing, carpentry and bricklaying, all skills that served him well as a missionary. In 1859 he set up Inyati (now Inyathi) mission station, the first permanent white settlement in Matabeleland, with William Sykes and John Moffat for the London Missionary Society (LMS) He established good relations with Mzilikazi and served as his doctor, but he traded in ivory and ostrich feathers to support his meagre salary and became involved in Lobengula’s successions. For these activities, the LMS discharged him from service in 1872. He wrote a book to fund his return to Matabeleland and established Shiloh mission station where he taught, traded, farmed and translated the New Testament into Sindebele until his death on 8 January 1884. After his death his widow stayed at Shiloh until 1889 when Jameson advised her to leave.

[17] None of the accounts mention the messages that passed between Jameson and Lobengula. Jameson message of 7 November 1893 requested that the King return to Bulawayo and guaranteed his safety. Lobengula’s reply came four days later and said he would come but asked what had happened to his envoys made up of his half-brother Ingubogubo, Ingubo and Mantuse who had been accompanied by James Dawson. They had arrived at Tuli, the BBP headquarters of Lt-Colonel Goold-Adams, where in an appalling misunderstanding, Ingubo and Mantuse were killed; the story of apparent treachery that Ingubogubo brought back explains much of Lobengula’s subsequent distrust and why he immediately continued trekking northwards.

[18] Most accounts refer to them as Sehuloholu and Petchan

[19] Robert Cary states that William Usher (1851 – 1916) who had long been a trader at Bulawayo and married Mzondwase Khumalo, a daughter of an amaNdebele induna heard that Lobengula had sent messengers to Forbes column with a bag of gold sovereigns and a message saying he was beaten and wished to discuss peace. The amaNdebele knew the gold had been delivered, but nobody seemed to know why the peace offer had been ignored by Forbes. He reported to Jameson who was initially sceptical of the story but decided it must be investigated. On 1 February 1894 James Dawson set off with Riley and two amaNdebele on an official mission to find Lobengula, but also to establish the fate of Allan Wilson and his comrades and to investigate the rumour about the gold. He carried a letter from Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner in Cape Town, stating that the King would be treated well and would not be exiled.

[20] At the subsequent trial of Daniel and Wilson it was established that they were in the rear of Forbes column.

[21] James Dawson was the thus first to view the bodies of Wilson and the other members of the Shangani Patrol after he concluded a peace deal with Mjaan, the most senior izinduna and was then taken to the battle-site where he buried their bodies. It was only then he learned that Lobengula had sent the two messengers with a letter and sovereigns which they gave two men in the rearguard. Only when Dawson’s letter reached Bulawayo by runner on 1 March 1894 was it confirmed that Allan Wilson and his comrades were dead, as was King Lobengula.

[22] Nobody who had been part of Forbes column admitted to any knowledge of the gold sovereigns, so the BSA Company initiated an enquiry. Two Officers’ orderlies of the Bechuanaland Border Police, William Charles Daniel and James Wilson (no relation of Allan Wilson) quickly became suspects; they had been gambling heavily with gold sovereigns and bought farms with cash; both were in the area on the day in question. Although they both denied guilt and were not recognized by Sehuloholu and Petchan and did not speak Sindebele beyond basic phrases; they were unable to say where their sovereigns had come from, beyond assertions of gambling. The two were lucky to escape lynching; the resident magistrate and four assessors found them guilty and sentenced them to fourteen years’ hard labour. However, this exceeded the Magistrates maximum sentencing powers of three months and they were soon released on the orders of Sir Henry Loch.

[23] Forbes had started from Bulawayo with 448 men, including 200 local amaNdebele carriers, without blankets and coats and only three days’ half rations. After fruitless detours to Inyati and the Bubi River, Forbes reduced his force to 254 men; 150 of the Victoria Rangers, 78 from the Bechuanaland Border Police, 21 from B Troop of the Salisbury Horse, and a handful of Raaff’s Rangers. After several days of painfully slow advance from Shiloh the force was reduced again to 158; with ten days half-rations on pack horses and just two Maxims. The force was on the south bank of the Shangani River at lunchtime on 3 December 1893. They could actually see amaNdebele cattle being driven away on the north bank and Forbes quickly sent Major Allan Wilson with a patrol of twelve men and eight officers across the Shangani River to search for Lobengula and return by nightfall.

[24] At 9pm Sergeant-Major Judge and Corporal Ebbage returned to camp saying the Wilson patrol had been following Lobengula’s wagon tracks and that he had requested more men and a Maxim gun in the morning.

At 11pm Captain Napier and Troopers Bain and Robertson brought another message from Wilson stating they would stay north of the river overnight close to Lobengula and requesting that Forbes bring the whole column across the river at 4am the next day.

At 1am on the 4 December 1893 Forbes sent Captain Borrow with twenty-one men (although Troopers Landsberg and Nesbitt became separated and returned to Forbes) and a message saying he had heard from a captive that his position was surrounded, and he expected to be attacked at any moment. Wilson at that time had thirty-seven men including himself.

[25] Most of the approximately three thousand amaNdebele warriors with Lobengula came from the remnants of the Imbizo, Ingubo and Insukamini regiments.

[26] Nguboyenja

[27] Nyamanda

[28] Each man had been issued with one hundred rounds; The Maxim guns were limited to two thousand one hundred rounds

[29] One of Lobengula’s chief councillors who died the same day

[30] Wilson sent back Captain Napier, Trooper Robertson and the scout Bain requesting reinforcements. They reached Forbes shortly before midnight. Shortly after midnight Forbes decided to send Henry Borrow and twenty men of B Troop to reinforce Wilson’s patrol together with Trooper Robertson as Pete Ingram as scouts.

[31] Sanibona in Zulu means hello or good day

[32] Lobengula’s wagon. Captain Napier called repeatedly in Sindebele for Lobengula to come out. Following his fifth call, Mjaan the izinduna ordered his riflemen to encircle the patrol, but Wilson ordered a retreat into the thick bush where they could hide until daybreak.

[33] Forbes heard the firing to the north and when they moved out of their laager, the three hundred amaNdebele sprung their ambush wounding five of his men. The engagement lasted about an hour and in that time the Shangani River came down in force from the rains the night before, making the drift impassable for the Maxim guns and their carriages.

[34] Wilson and his men retreated toward the Shangani hoping to meet up with Forbes but were soon blocked by a line of AmaNdebele. Refusing to abandon his wounded, Wilson sent the American Scouts Frederick Russell Burnham, Pete ‘Pearl’ Ingram and Australian Trooper William Gooding to charge through the line and get reinforcements. The three horsemen reached the flooded Shangani at 8am and crossed with great difficulty knowing that the rescue of Wilson and his patrol was no longer possible.

[35] Major Patrick Forbes force on the south bank of the Shangani River had three Maxim guns, but no artillery with them.

[36] Ginyalitsha was speaking nearly 44 years after the event when he would have been familiar with the words and sound of God Save the Queen

[37] Corroborating evidence that the fight lasted until after midday. Induna Sivalo Mahlana stated in another oral account: “So all the white men died with a great number of Matabele…In the afternoon the Matabele picked out their dead to bury them, and on the morrow they did likewise. Others were covered with branches of the trees and bushes, both black and white. Not a garment was taken from the dead: they were all left as they fell, to be devoured by the vultures and the wolves.”

[38] i.e. the floodwaters of the Shangani River had risen and receded within 18 hours

[39] Robert Cary thought Lobengula died of malaria; others speculate that Lobengula and Magwegwe took poison.

[40] One of the tribes now classed as Mashonas who were subjected by the amaNdebele

[41] The Batonga people of Zimbabwe / Zambia are settled around the Binga district, along the shores of Lake Kariba and other parts of Matabeleland

[42] James Dawson published a description by Mjaan of how he laid King Lobengula to rest. He said he buried him in all his feathers and his finery, with his shields and assegais, and all the rest of the royal paraphernalia. He set him up in a cave in the face of the rock, where, after fixing him properly, he stuck his assegai in the late King’s stomach, and the calf of the elephant belched. Mjaan was then satisfied that he had done his work properly and closed the cave up. I should perhaps explain that native etiquette demands that, after a feast, a guest belches freely as a sign that wants have been fully satisfied.

[43] Spelt Loskey by P.D. Crewe, but Lozigeyi Dhlodhlo according to the website Bulawayo1872.com and sometimes spelt Lozikeyi

[44] Chief or leader

[45] Whites or Europeans

[46] Ponchos or capes

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: