Thomas Baines – more paintings from his Zambezi journey

Thomas Baines – more paintings from his Zambezi journey

Much of the detail of the Zambezi Expedition is already discussed in the article Thomas Baines’ disastrous 1858-9 Zambezi Expedition with David Livingstone. This article concentrates on the sketches and paintings of local scenes and people that Baines painted as a member of the 1858-9 Zambezi Expedition.

The Zambezi Expedition

In late 1857 civic and academic institutions were heaping David Livingstone with honours after his epic lone journey across the African continent from Luanda in Angola to Quelimane in Mozambique. He had amicably severed his connection with the London Missionary Society in May and offered his services to the Foreign Minister Lord Clarendon to open up the interior of Southern Africa to British commerce by way of the Zambezi river.

His descriptions in Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa of the fertile lands suitable for cotton, indigo, sugar and cattle suggested a land of promise which was open to trade and civilisation and Dr Livingstone seemed the most likely candidate to lead an expedition. His suggestions on the future project to Lord Clarendon were that England and Portugal should combine; “to open South Central Africa to the commerce of the world” by the Zambezi river which: “appears to present an eligible path into the interior from the east coast.”

He told a meeting: “What I want to do is to get in the thin edge of the wedge and then leave it to be driven home by English Energy and English Spirit.”[i] His ultimate intention was to put an end to slavery by introducing alternative legitimate commerce to south central Africa.

The Royal Society, the Royal Geographical Society and the Geological Society were invited to assist. Doubtless Dr Livingstone would have preferred to be sent out alone with plentiful supplies, but John Washington who had been deputed to act for the Government felt that something should be done to secure scientific information on the region and its potential and so despite his misgivings Dr Livingstone requested a general assistant and ‘moral agent’, an economic botanist, a geologist, a surgeon, an engineer, a navigating officer and an artist who might also serve as trader and store-keeper.

Thomas Baines selected in the artist-storekeeper role

Dr Livingstone was at Somerset House, the home of the Royal Geographical Society in November 1857 to hear Baines, who had been elected a fellow of the RGS on 23 November; Dr Livingstone would have heard Baines read his notes of his Australian travels and seen the pictures he exhibited. It is known that they discussed the need for a light boat for navigating the shallow waters because in the new year Baines built a model in metal of a full-scale boat that was 30 feet long with a 6-foot beam and capable of carrying sixteen people. Built in air-tight sections, it would be unsinkable and light to carry.

However, Dr Livingstone chose to take two whale-boats and borrowed a pinnace from HMS Hermes; but all were too heavy to portage around the cataracts of the Zambezi and Shire rivers. Baines wrote ten years later: “When we reached the Zambezi it was a matter of frequent regret that we had not some form of boat portable enough to be carried over rough country to rivers we wished to navigate.” [ii]

On 11 January 1858 Sir Roderick Murchison announced Baines’ appointment as artist-storekeeper with the names of his colleagues. Charles Livingstone as ‘moral agent,’ Dr John Kirk as botanist and medical doctor, Richard Thornton as geologist, George Rae as engineer and Commander Bedingfield RN who had navigated the Congo river as navigating officer and second-in-command.

The voyage to Cape Town

Until they left Liverpool on the 3 March Baines was fully occupied collecting the stores ordered by his colleagues. The party would be accompanied by Mrs Mary Livingstone and even on board the Ceylon steamer Pearl there was much preparation for the work ahead and Baines was fully occupied. John Kirk wrote: “Mr Baines is a trump and does more than anyone else; if anything is required from any case in the hold, he is down, working and sweating…I am sorry he is not very well, as he has caught a cold working in the hold.” Mrs Livingstone was: “as thin as a lath” from fever and seasickness, but was collected at Cape Town by the Moffat’s who took charge of her and restored her health.

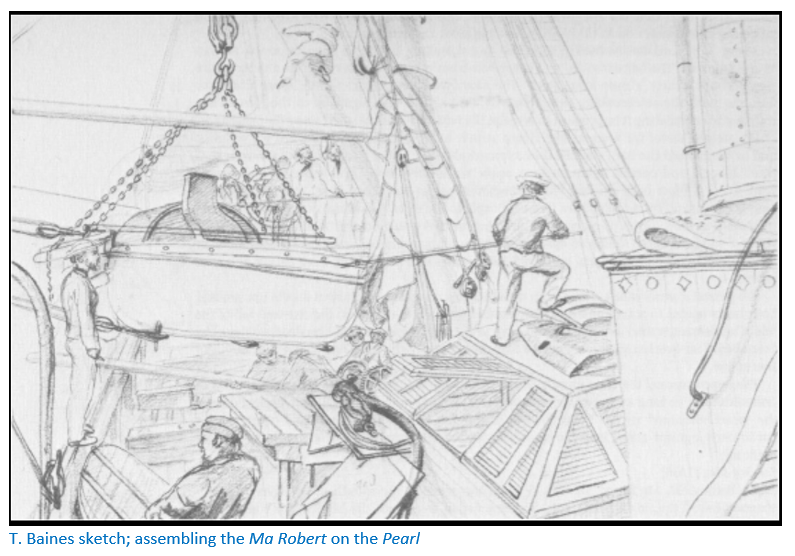

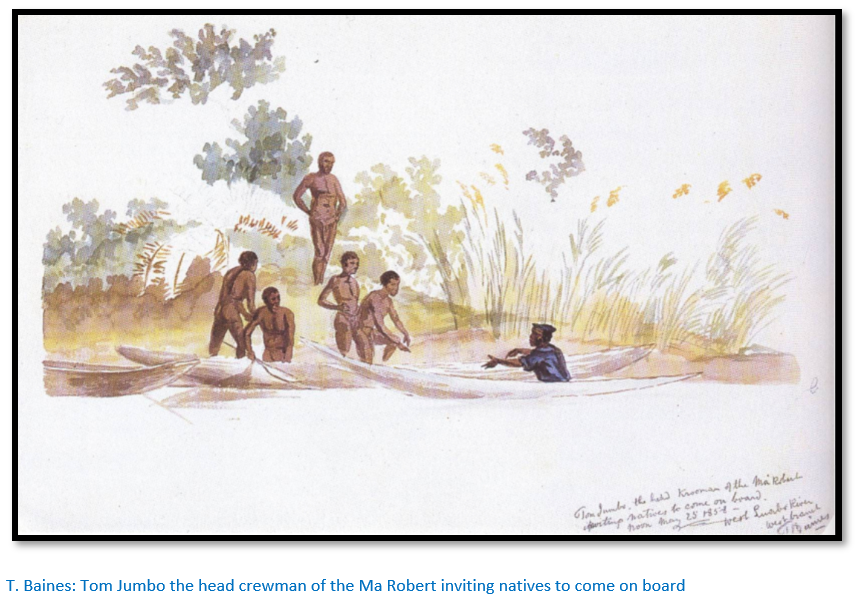

The Pearl put to sea from Simonstown accompanied by HMS Hermes and on Friday 14 May crossed the bar of the Zambezi river mouth. By the following Wednesday the sections of the Ma Robert had been joined together and on the 24 May they explored the weed-choked channel of the West Luabo for a way into the Zambezi.

Tensions on the Zambezi

Despite being informed that the Portuguese had been driven from all their stations on the Zambezi, that Quelimane was full of refugees, that Tete was under siege and being given the advice that local natives would obstruct their passage the party continued their search until Captain Skead found the Kongone mouth which ran deep and straight and linked with the Zambezi with a natural channel eight kilometres long.

Dr Livingstone knew how tenuous the Portuguese hold on the territory of Mozambique actually was and how much the Portuguese were disliked by local natives and he was sure the British flag would be recognised and respected as a symbol of fair dealing.

Difficulties of transporting stores to Tete

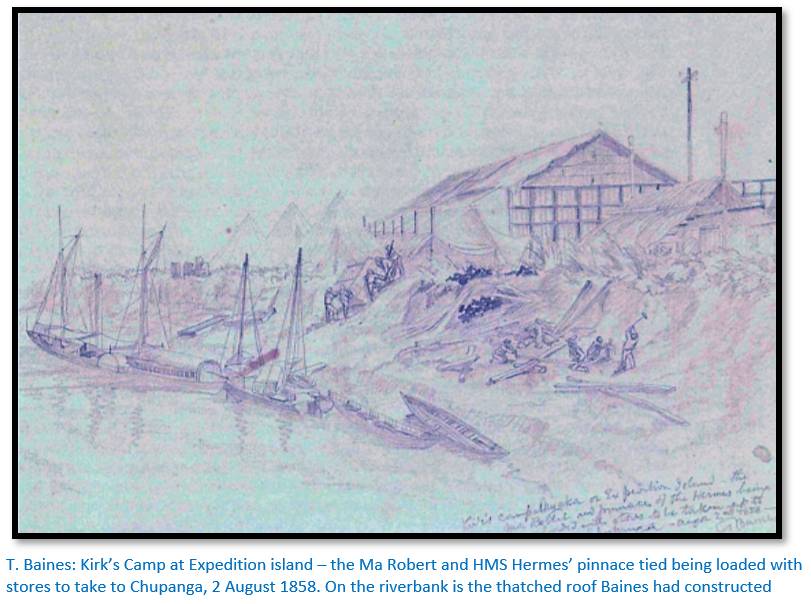

Far from being easy to navigate, the Zambezi was full of shoals and islands – too shallow for the Pearl to navigate and everything had to be unloaded at Expedition Island, sixty-five kilometres from the Zambezi mouth and then shipped on the Ma Robert to Sena and then Tete. Overloaded the Ma Robert drew 27 inches (70 cm) her certified draught being 14 inches (36 cm)

Baines had worked harder than anyone in the “harassing and dirty” unloading of the Pearl and when he set up the corrugated iron house they brought with them he found the roof had been left behind; so he had it covered with a tarpaulin and the roof thatched by local natives. Kirk says that in addition to sketching Baines: “did more than his share of the rough work.” However Kirk also noted that the European members of the expedition were not coming together as a team. Dr Livingstone issued orders and instructions but showed little interest in any of the members and Bedingfield grumbled incessantly at the awkward handling of the Ma Robert; the “Asthmatic” as she was called; it appeared Dr Livingstone was beginning to regret having a team of Europeans; local natives gave him no such trouble.

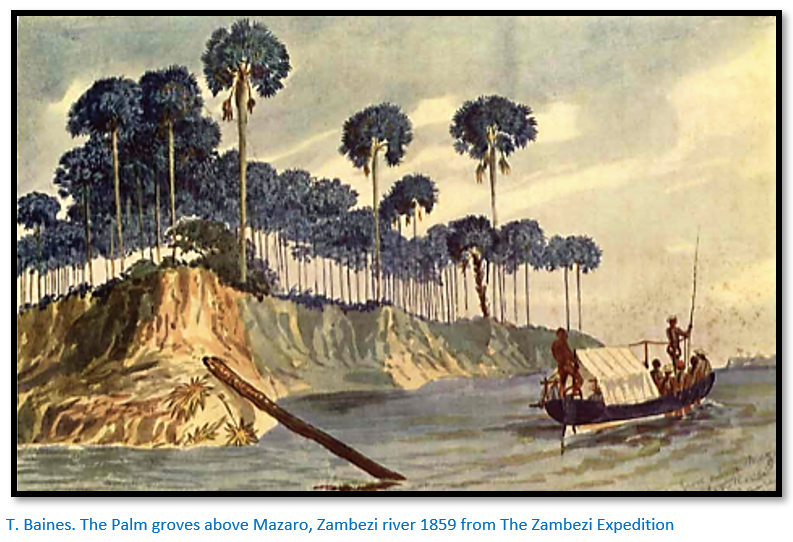

Dr Livingstone took Baines with him when the Ma Robert left Expedition island towing a heavily-laden whaleboat and the pinnace. On the third day they reached Mazaro, a Portuguese military headquarters and on landing almost stumbled over two headless and mutilated bodies. Here they witnessed a hundred or more native levies armed with ancient muskets, assegais and bows leave the stockade with no enthusiasm to fight the rebels. Very little fighting took place although Baines was given permission to make a sketch of the lacklustre battle which took place and which appears with many others in Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambezi and its tributaries by David and Charles Livingstone although Baines was not credited as the artist.

The Portuguese Governor at Mazaro was sick and took passage with them until they reached the double hill at Sena and the party landed and walked in the dark to the stockade defending the town where a sentry removed some of the poles to admit them. The commandant’s men were at Mazaro and villagers at Sena were enlisted to help. After unloading the stores including a saw-mill engine: “no end of shouting and misdirected exertion” Baines returned with the Ma Robert down the Zambezi to Expedition Island for the next load.

It was only by 16 August that the Ma Robert with the pinnace and two whaleboats in tow brought up the last load of stores to Sena. Navigating through the endless shoals was a ticklish job; the guide, a slave named Scissors of whom Baines said: “Livingstone directed me to accompany him in the boat with a perfectly useless pilot who seldom recognised sandbanks until he hit them”[iii] and the Ma Roberts the “Asthmatic” lived up to her name. Although her boiler fire was started at 2am, steam was up only by 8am and then she was so slow that light native skiffs easily left her behind.

By this time commander Bedingfield’s resignation had been accepted by Dr Livingstone and the native crews had been told that Bedingfield was no longer in command and that no orders were to be taken from him. The “Asthmatic” problems and the torturous navigation along the Zambezi had resulted in endless grumbles from him and in a small party he had a negative effect on morale.

Respite at Chupanga

Over-exertion on Exhibition island in dismantling the house had caused Baines sunstroke with some delirium and he was so ill that Dr Livingstone left him at Chupanga where Colonel Nunez had his headquarters ‘the house of Shupanga’ with a native village close by on the south bank of the Zambezi. In front was the gigantic baobab tree that was afterwards to shade Mary Livingstone’s grave.

Here Baines and Kirk enjoyed a healing break in the cooling shade of the house and from the thatched verandah looked over lawns to the river. Outside the window slaves sang war songs and Baines noted Zulus present who had fled the Mfecane in the south and joined the Portuguese forces.

The Expedition at Sena

Once they reached Sena the expedition members were greeted with great courtesy especially by Senor Ferrão and Major Sicard, the commandant at Tete, who were genuinely interested in the objects of the expedition and the Major offered to take up their supplies to Tete in canoes once the insurrection was over.

Journey continues to Tete

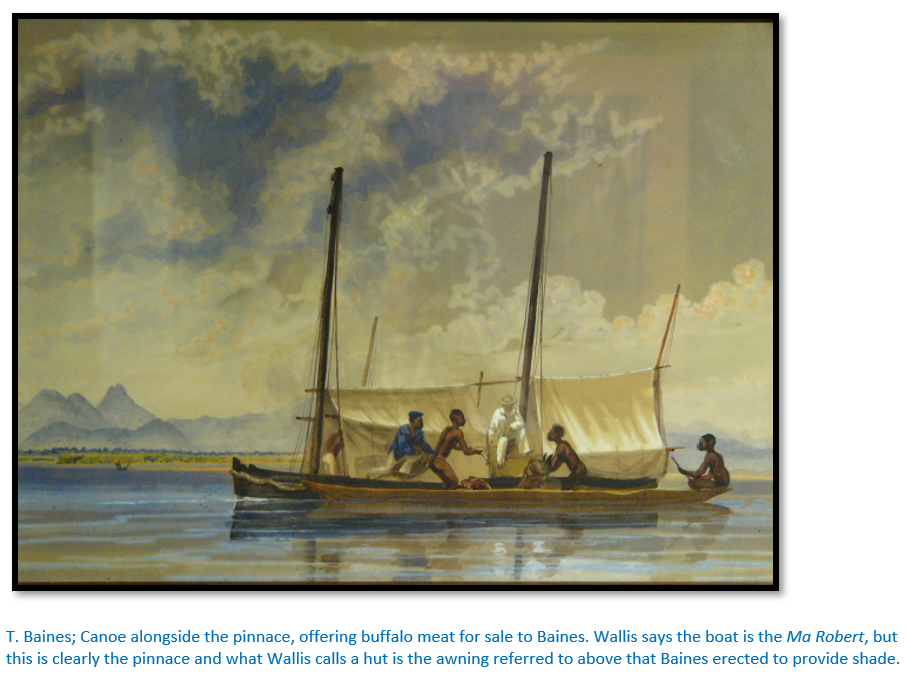

When their journey continued the Ma Robert often grounded dangerously and it was obvious her feeble engine did not have the pulling power to tow the two whaleboats and pinnace. Baines volunteered to stay behind with the pinnace whilst Dr Livingstone pushed on ahead. He rigged an awning over the pinnace, fitted a new tiller to the whaler and roamed ashore noting the people and doing some sketches. Eventually he had to move to mid-stream to escape the local natives who were coming to sell or beg before taking the pinnace upstream and meeting Dr Livingstone on the Ma Robert returning from Tete.

Dr Livingstone wrote in his diary; “Came down this morning to near Nyamotobsi island and found Mr Baines in good health. He had engaged himself much and made some nice sketches. He had managed to come up a few miles with the wind and had arranged his pinnace rather tastefully. I left him where I found him, as it was important to make all haste down and then return.”

Major Sicard found Baines with fever and very short of supplies with no bread, meal or rice. He took much of the pinnace’s freight into his own canoes, gave him food and lent him crew men for the pinnace. In return Baines gave him ten tins of sardines and a cheese; a gift that was to have major repercussions later.

With Major Sicard’s men poling the pinnace moved slowly up the Zambezi followed by the whaleboat. Here the river was 5 – 8 kilometres wide and very shallow because it was the dry season but when they reached the Lupata Gorge the river ran in a ravine 11 kilometres long and the surrounding hills rose sheer from the water-edge. Here the waters flowed deep and swiftly and after passing the stockade of Bongo, home of escaped slaves defying the Portuguese but accepting the English as friends, they came to Tete on the south bank.

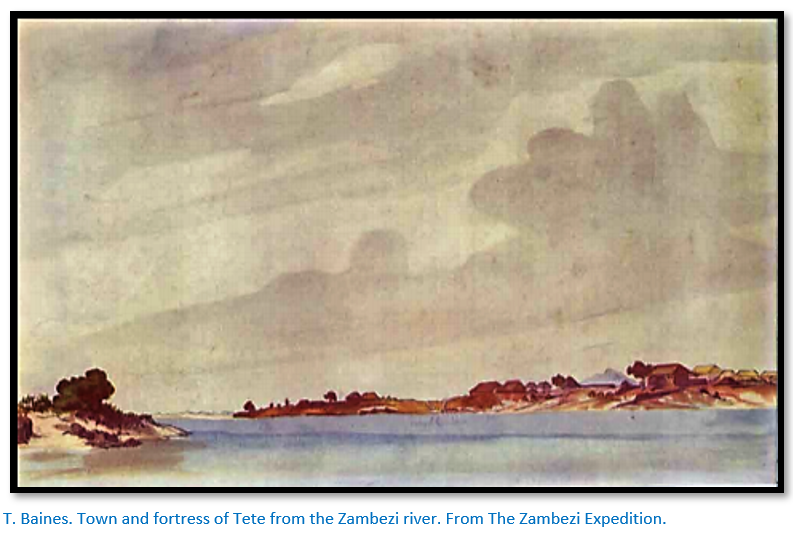

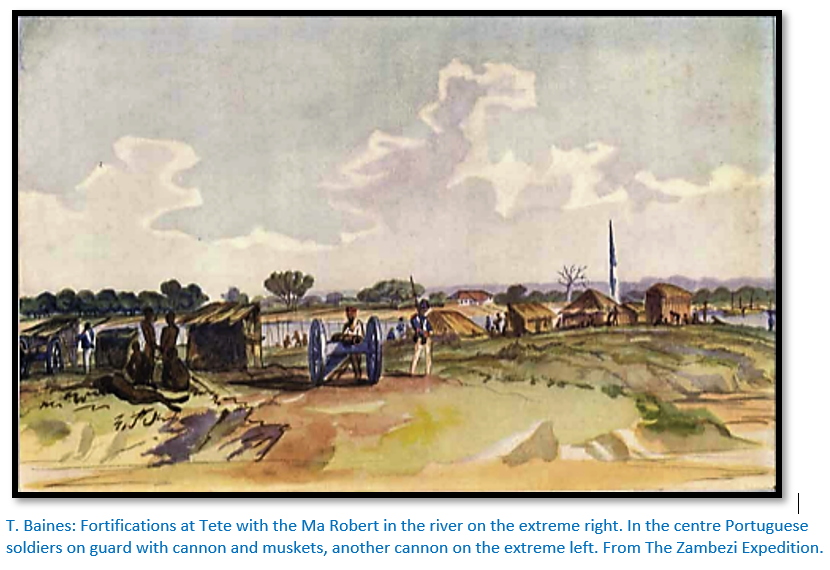

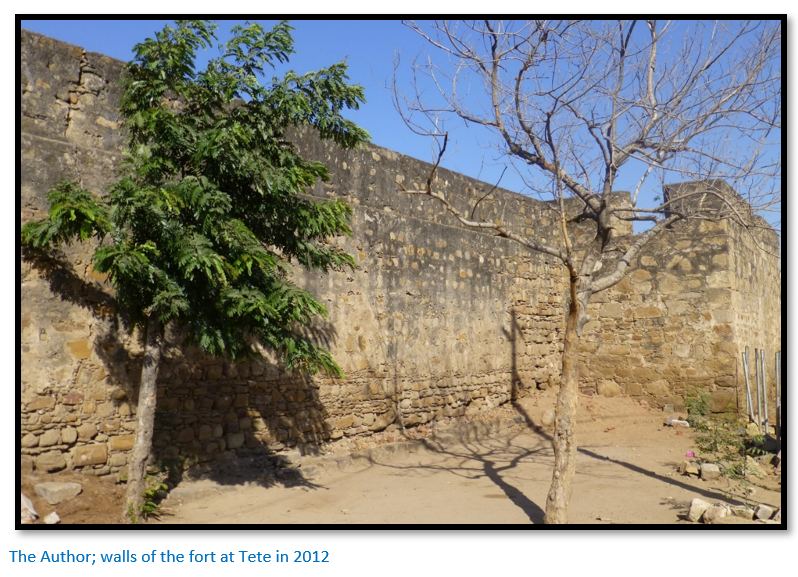

Tete

A wall of stone and mud surrounded the fort, church and Portuguese houses. Here Baines met Charles Livingstone and Rae and Dr Livingstone’s faithful Makololo who were left behind from his 1856 Expedition to await his return. During their three year stay at Tete some had married and settled down and showed little inclination to return to their homes.

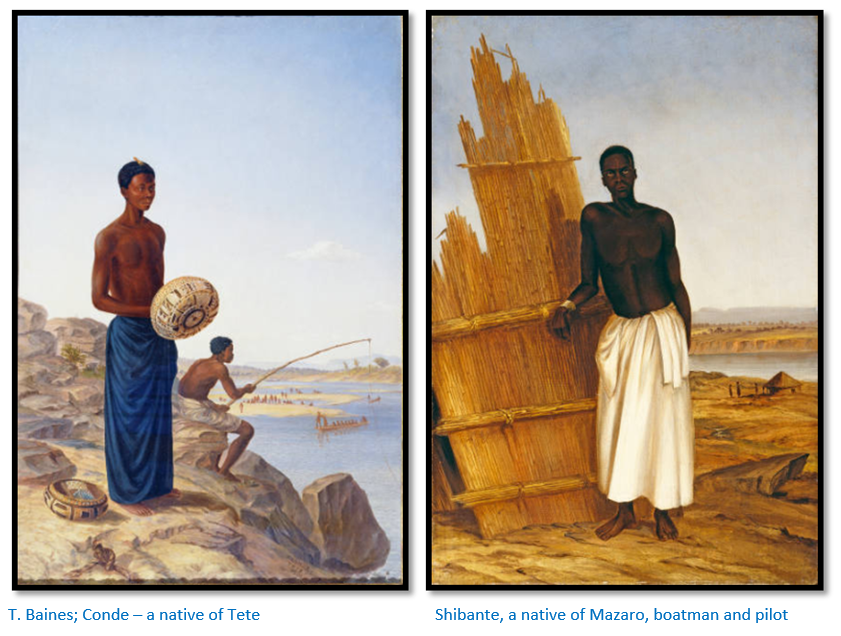

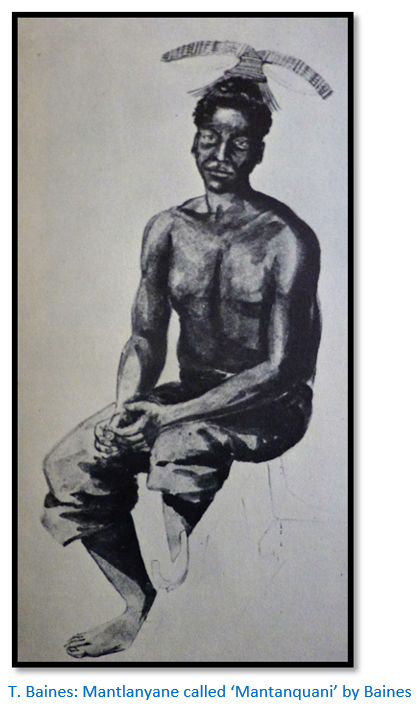

On his first trans-Africa journey Dr Livingstone left a number of his Makololo followers at Tete to await his return, amongst them Mantlanyane described by Baines as; “Mantanquani, Makololo in the service of Dr Livingstone wearing a comb of bamboo made in the country of Shimbe…he is now sitting on one of our whaleboats – most likely a Batoka or riverman of the Zambezi, one of the tribes conquered by the Makololo 5 December 1859, mouth of the Kongone.”

Baines’ fever left him and following Dr Livingstone’s orders he began mapping the stretches of river below Tete but the task was incomplete when on 3 November Dr Livingstone and Kirk returned from the Kongone; all at Tete were reported to be: “in good health except Baines, whose head is still a little touched by the sunstroke of the island.”

Tete was the last Portuguese outpost on the Zambezi and on the 8th November Dr Livingstone took a party up to the Cahora Bassa gorge [then called Kebrabassa] and its rapids, but left Baines and Thornton who were ill and Charles Livingstone who wished to practise his photography.

Cahora Bassa makes the Zambezi river impassable

The visit to Cahora Bassa gorge had been a disaster…the river here was closed to boats and Dr Livingstone took out his frustration on Baines “scarcely off the sick list and I should say, the hardest working member of the expedition” for some alleged omission in feeding the Makololo which Kirk attributed to the vagueness of Dr Livingstone’s instructions. His own brother Charles Livingstone said: “the members of the expedition did not get orders what to do and were always at a loss how to act.”[iv] Two years later another witness watching Dr Livingstone direct an operation declared: “I never saw such constant vacillation, blunders, delays and want of common thought and foresight.”[v]

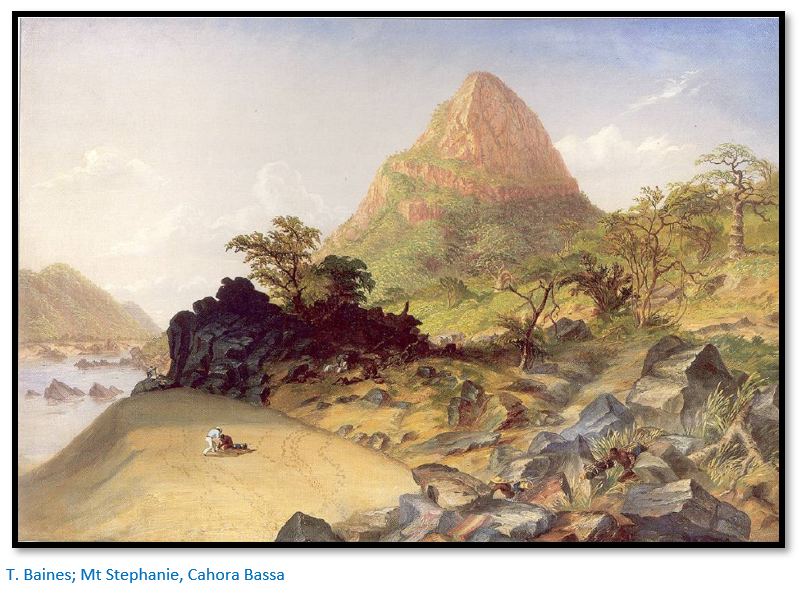

On 24 November a larger party consisting of Dr Livingstone, Kirk, Thornton, Baines and local natives went by boat to the entrance of the Cahora Bassa gorge, there was no possibility of making headway in the broken waters ahead and they walked overland along the Zambezi riverbanks. Baines made several sketches of the cataracts which are included in the article Thomas Baines’ disastrous 1858-9 Zambezi Expedition with David Livingstone on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Dr Livingstone had initially been told by their guide José Santa Anna after seeing only “a small but by no means rapid waterfall” that there were no further obstacles to navigation and the party then climbed a steep hill which Dr Livingstone named Mount Stephanie. [Stephanie married King Peter V of Portugal on 18 May 1858 but she died of diphtheria next year aged 22 years]

Then one of his Makololo stated there were far larger cataracts higher up the gorge. Since only he knew the Makololo language Dr Livingstone kept this news to himself and only grudgingly agreed that Kirk could accompany him up the gorge to establish the truth.

So it was on this second visit to the Cahora Bassa gorge that Dr Livingstone came to accept that no boat would navigate this stretch of the Zambezi. It was a shattered and disillusioned Dr Livingstone who returned to Tete, but even then Kirk who saw Dr Livingstone’s report to the Foreign Office, thought it was still much too optimistic.

Livingstone’s disappointment turns to bitterness

Dr Livingstone in his bitterness at this setback blamed others. The Ma Robert had thwarted him and should be replaced. His assistants were constantly sick; they could: “smoke their pipes and wait for his return at Tete.” Yet his brother Charles, not only the weakest member of the party but also the idlest and most mischievous was exempt from any criticism. Kirk calls him lazy and was irritated by his dandyism and his: “lounging indoors and never exposing himself without an umbrella and felt hat with all the appurtenances of an English gentleman of a well-regulated family, though, when work was to be done, the rest set about it without regard to dress or appearance.”[vi]

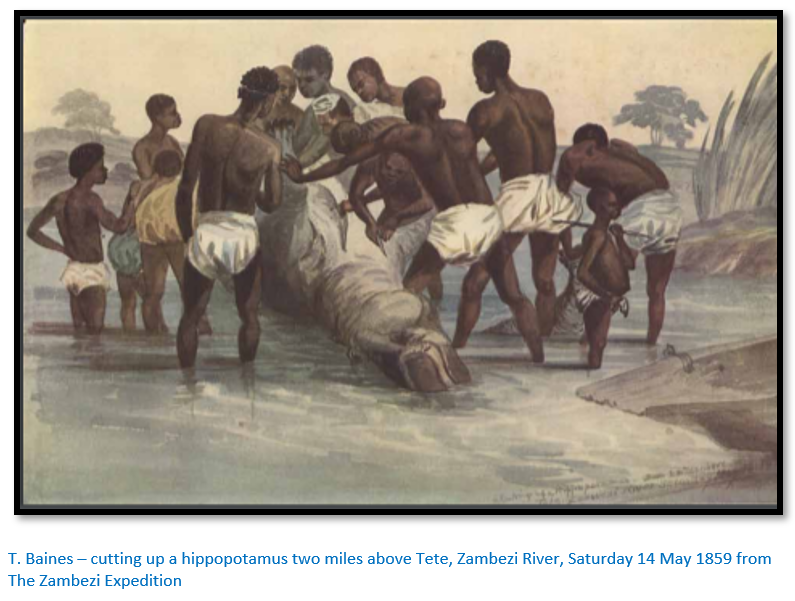

Walking tired Charles and the others had to halt so he could rest: Kirk wrote: “Mr L. to have a snooze every half hour or so…at each of these rests Baines and I practise at the Hippopotami.” Charles behaved towards the natives with violent language and a bad temper. Once he kicked the Makololo headman who levelled his spear at Charles and only respect for his brother restrained him. Even Dr Livingstone in his diary wrote that: ”the one mistake of the Expedition had been bringing Charles into it.”

Kirk and Dr Livingstone returned from their second exploration up the Cahora Bassa gorge: “lean and haggard, as if from long illness.” The Zambezi river would not be ‘God’s pathway’ into the interior and therefore Dr Livingstone concluded he would seek an alternative route along the Shire river.

Baines attempts to establish if the Cahora Bassa gorge is navigable in the floods

On 18 January 1859 Charles and Baines with a Makololo crew hauled the boat up through the flood waters with a rope; many of the rocks previously visible were now submerged and the river now had waves four or five feet high with whirlpools that threatened to pull the boat from their grasp. Eventually they could go no further and hauled the boat into a small cove in a sandy islet and continued the journey on foot. Charles soon complained of a touch of fever and went back to the boat; but Baines continued with a Makololo to carry his bedding until he too was left behind and Baines carried on alone climbing over fearsome boulders beside the river until his path was arrested by a steep cliff. He turned away from the river and climbing the steep slopes to look down on the Morumba rapids and after sketching the scene retraced his steps.

After two days of exhausting travel Baines reached his Makololo assistant and hurried on down to join the others only to find they had left. Their food was finished, but next day they reached the boat and in the afternoon of 3 February 1859 they reached Tete where they found Dr Livingstone and Kirk had just returned from the Shire river.

Over-exertion and exposure brought out fever again in Baines but by mid-February he had recovered. A month later Dr Livingstone took Kirk on a more extended exploration of the Shire river and again left his brother Charles in charge at Tete.

Left at Tete

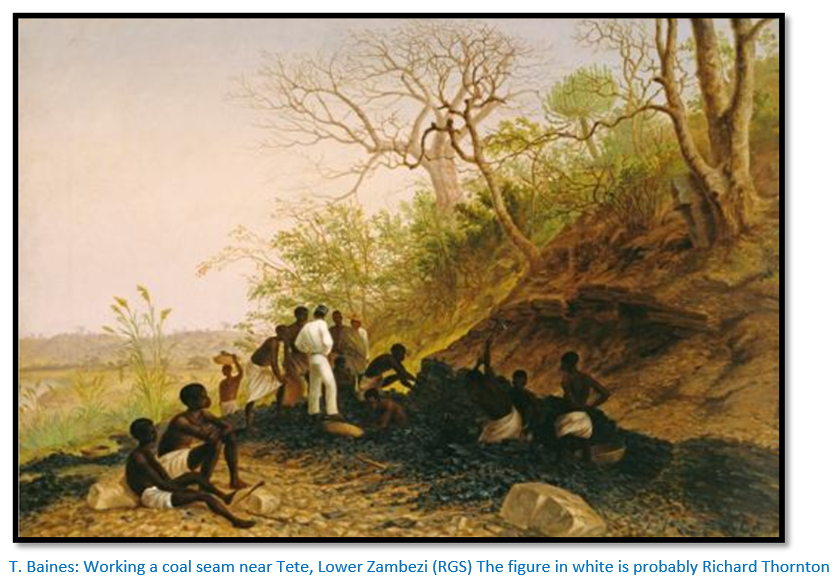

Dr Livingstone left those at Tete with various duties. Charles was to investigate the country to the south-west following rumours of gold, but news of unrest in the interior made him stay in Tete and make a collection of birds instead. Richard Thornton was to cross the river and explore the coal seams at Moatize. George Rae was given general maintenance duties. Baines had to safeguard the stores and make sketches.

Baines accused of theft

Scarcely had Dr Livingstone and Kirk left when Charles charged Baines; “with having given away the property of the Expedition in such a manner as to lay himself open to prosecution.” This Baines flatly denied. Charles had refused to give Baines a place where the expedition’s stores could be kept under lock and key, so they were stored under tarpaulins near their accommodation.

Charles in his report to his brother also said that Baines had gone skylarking in the whaler on the river with his Portuguese friends and had spent expedition time and materials in painting portraits of his friends the Portuguese officials.

There are hints that Dr Livingstone and Baines talked things over with Baines offering to continue to make sketches without a salary – later this would be construed as an admission of guilt, but there is plenty of evidence that money was not a motivating factor in Baines’ life.

Dr Livingstone also countermanded his brothers orders and found a secure place for the expedition’s stores.

His letter to Baines is not quoted here as it bears all the marks of Charles’ influence. On the boat trip to Sena he had Charles to constantly remind him of Baines alleged failings and the quote from his diary is much more telling: “Found that a piece of serge belonging to Mr Rae had disappeared and was in Baines’ box. He gave away the mess wine to the Portuguese whenever they called on him – I saw him once myself – and then when he had finished it declared that it had been fairly drunk at the mess table. He uniformly took precious sharp care of his own things while secretly giving away the goods of the Expedition, painted the portraits of Generoso, Pascoal and Albino without authority and then when he had quite destroyed the whaler declared she was none the worse ‘not a whit.’ On reflecting on the matter I resolved to send the following and did so by Augustino, requesting Major Sicard to take charge.”

The ‘following’ was a letter from Sena dismissing Baines from the Expedition from the 31 July; his pay stopping the same date. Baines was allowed to use the expedition materials for his art until he was sent home – no doubt this justified in Dr Livingstone’s eyes his use of Baines’ paintings without crediting him. In Wallis’ words Charles word was taken without question and Baines’ good name blasted without opportunity given him to defend himself.[vii]

Baines response to the accusations

Dr Livingstone’s letter to Baines only reached him on 6 September 1859. Baines replied quickly rebutting the charges, but also confirming he had handed over the stores to Major Sicard, the commandant at Tete. Baines confirmed he had given the Major some expedition stores when he had helped with getting the pinnace up to Tete [ten tins of sardines and a cheese] but they were an acknowledgement of help given to the Expedition, not to himself. In instances where he had given out similar presents, he believed that Dr Livingstone would have agreed to them.

As for the five portraits of Portuguese officials; two had been painted on Dr Livingstone’s instructions, the third had been reported and not objected to. Nothing is said of the remaining two.

In a place as small as Tete it is inconceivable that Baines could have given away ‘large quantities of public property’ and Baines appealed to Major Sicard who replied that nothing had come to light that supported Dr Livingstone’s charges and he promised to write with that message.

Accusations against Richard Thornton the Geologist

Thornton like Baines had been dogged with sickness and found the climate sapped him of energy; he had begged to be invalided home, but Kirk as the expedition doctor did not concur with this action. Whilst Thornton had been cataloguing his specimens at Tete, Charles had crossed the river and inspected Thornton’s work at Moatize which he wrote in his report was unsatisfactory.

On 25 June he was dismissed from the Expedition with his pay stopped from 3 May; the date he was alleged to have stopped work.

Baines paintings around Tete

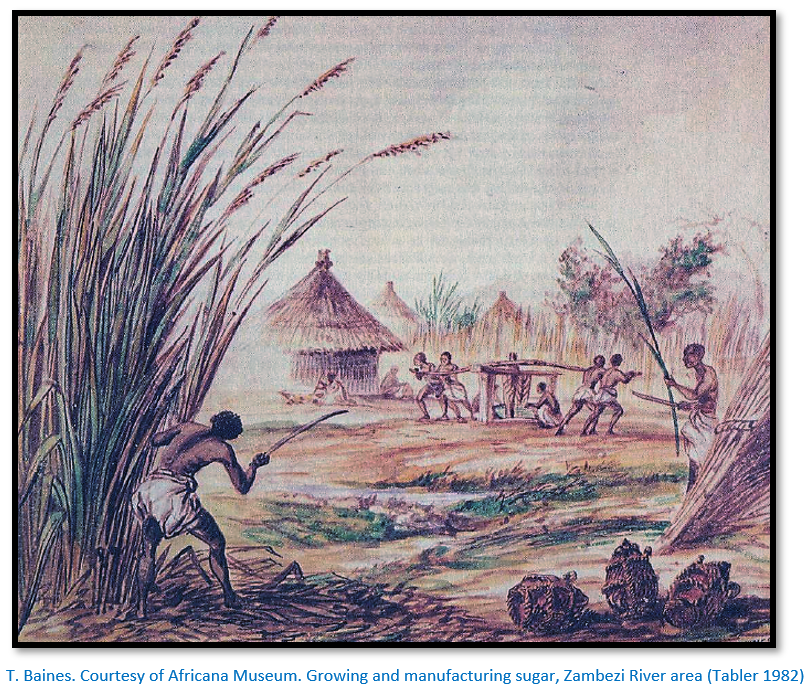

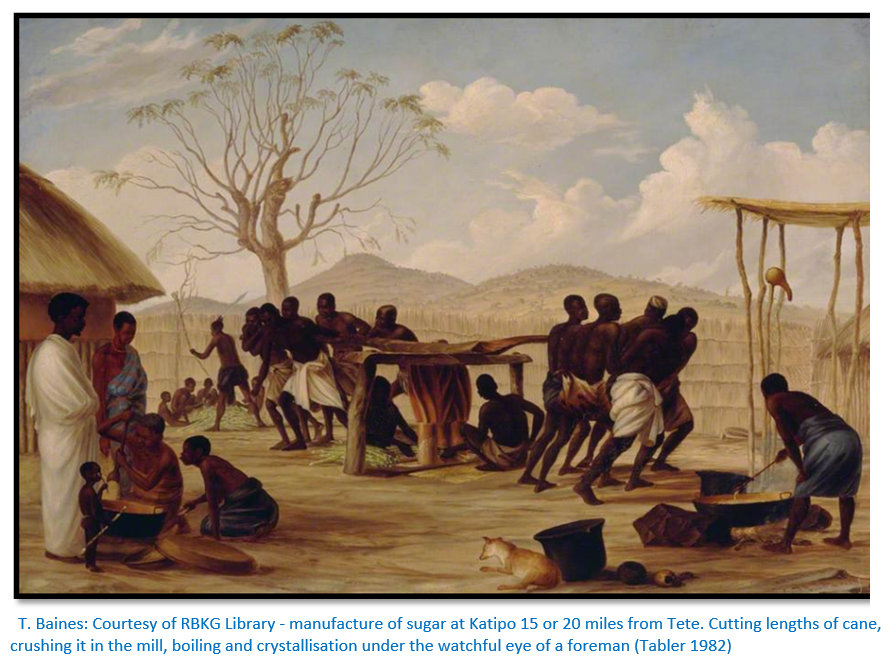

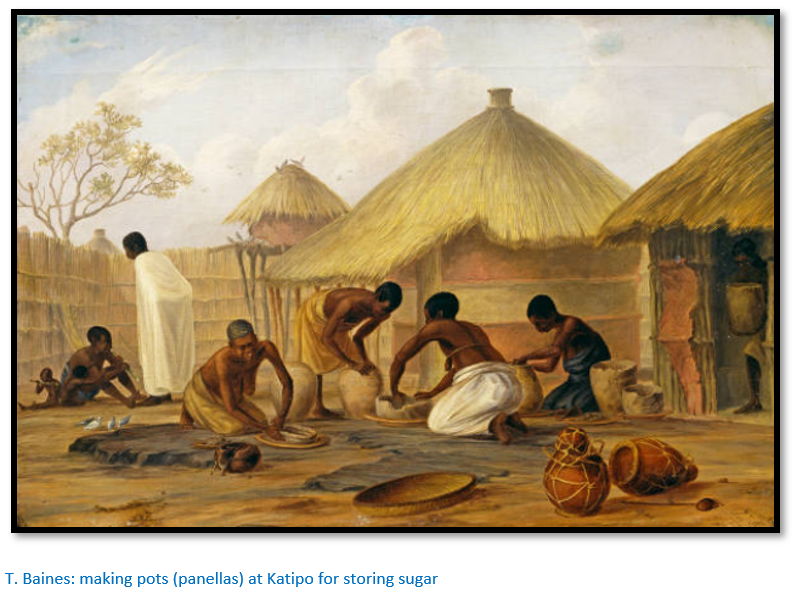

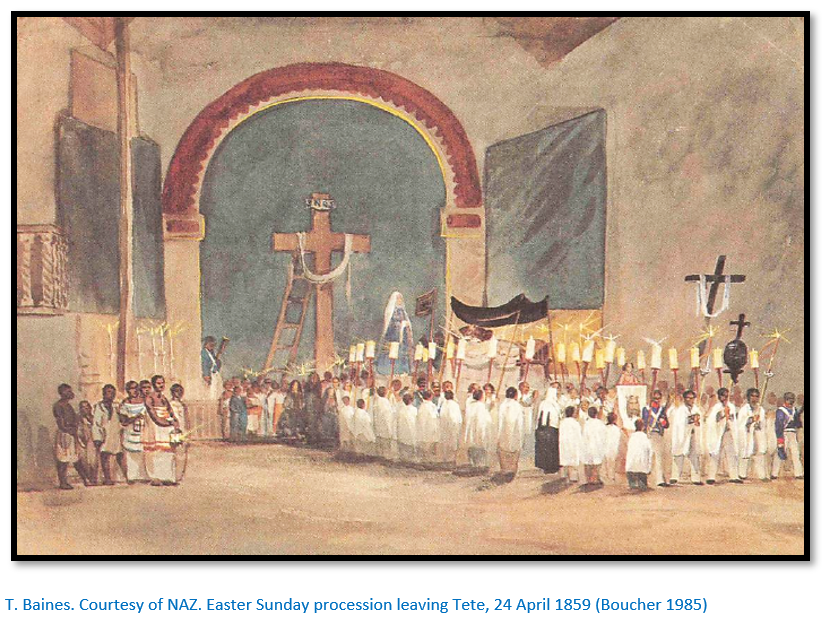

Baines made a number of excursions in the neighbourhood of Tete, with Major Sicard’s aide-de-camp he visited a sugar plantation on 27 July, attended the Easter Sunday service and was present at a wedding in Tete – watercolours were produced of each and shown below.

The whole process of sugar manufacture is shown here in this panorama. On the far left sugar cane is pulverised with machetes before being squeezed in a press in the centre. The cane juice is boiled on the far right concentrating the mixture into crystals and the resulting sugar concentrate is broken up in the left foreground under the eyes of a foreman.

Baines lived quietly, never going far from Tete as it seemed he still wished to keep an eye on the expedition stores now under the care of Major Sicard.

On the 25 July Kirk and Rae returned to Tete after a month’s march south from Lake Nyassa – a journey so difficult they nearly perished. Kirk had a letter from Dr Livingstone which stated that since Major Sicard had found no evidence of theft that Baines must have secretly disposed of expedition supplies and had: “been in the habit of secreting expedition property in his private boxes.” Kirk was authorised to search Baines’ boxes and remove any property belonging to the expedition. He was also to question Baines over five jars of butter and five barrels of loaf-sugar not accounted for.

Kirk was to record Baines answers in the store book which was to be taken with Baines and Thornton down to Kongone to await a warship which would take the two men to Cape Town.

Charles Livingstone’s hand was behind the vendetta and Kirk states in his diary that Charles had been “horribly disagreeable” on the journey down from Lake Nyassa; it was clear he bore a great grudge against Baines. Kirk searched Baines’ private boxes and nothing came to light except two yards of naval canvas which Baines said was from his earlier Australian Expedition.

Once Kirk’s distasteful task was complete Baines took him to Major Sicard who stated that he had investigated the allegations regarding expedition property: “and fully satisfied himself that the charge was a calumny.”[viii]

The Portuguese at Tete are reluctant to see Baines leave

Richard Thornton had already gone downstream, now it was Baines’ turn, but the Portuguese at Tete banded together to prevent Kirk from hiring either a boat or canoe. At a meeting on 1 November 1859 called by Major Sicard they told Kirk: “the whole of the Portuguese present state that they will give us no sailors nor let us have sailors if they can prevent it.” They did not want to see Baines leave under these circumstances.

In the end Kirk managed to get a canoe and men and they left – Baines was sick with fever when he re-joined his former colleagues on Expedition Island.

Baines treated with ignominy at Expedition Island

Accompanying Baines from Tete was a letter from General Generoso that Dr Livingstone described as “an impudent letter.” This plus the trouble securing a boat and crew at Tete were put down to Baines stirring up the Portuguese at Tete against Dr Livingstone. In fact the Portuguese had been extremely hospitable and assisted the Zambezi Expedition whenever help was required and clearly the uncomfortable climate and expedition difficulties made Thornton and Baines useful scapegoats for Dr Livingstone’s malignant thoughts. Kirk in his diary calls the doctor at times irrationally “savage.”

Called into Dr Livingstone’s hut on 23 November 1859 for examination and called “thief” at the outset, Baines believed his case had already been judged. But for instance, one of the charges laid against him was that he had damaged the whaleboat while out skylarking with Portuguese officials. In reality the damage to the whaleboat was caused by a sudden squall so that she capsized at her moorings. Baines had been ill with fever in his hut, but on hearing of the mishap had gone down to help. Questions relating to money owing to Dr Livingstone are solved as the Doctor’s own diaries record he was repaid. The alleged theft of butter was not brought up; Baines was said to have covered up the theft of the sugar in his stock books, but nobody could point out where this had been done. The trivial matters of the canvas and portraits was not even brought up.

Despite all the allegations being unproven and denied, clearly Doctor Livingstone had been persuaded of Baines guilt by his brother Charles – he was forced to live apart in one of the whale-boats with a sail as an awning. The Doctor wrote: “I did not allow Baines to come to our table but send him a good share of all we eat ourselves.”

His colleagues were more humane. They helped Baines with money and with clothes as his private boxes stayed at Tete with his personal belongings and notes and many of his pictures and sketches…most of which he never saw again.

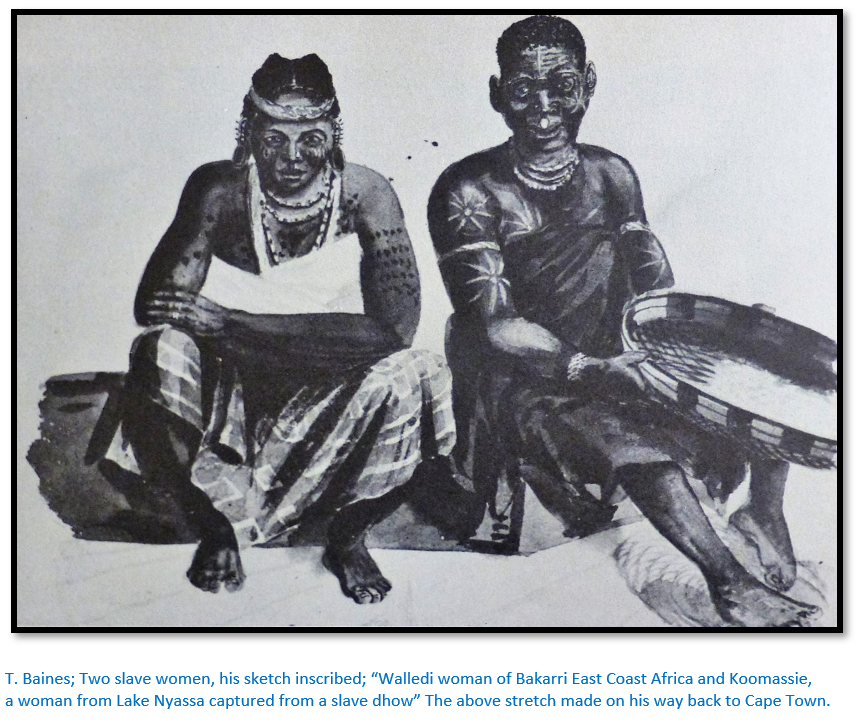

On 20th December 1859 Baines set sail for Cape Town in HMS Lynx. The naval officers treated him kindly; Lieutenant Medlicott telling him that Kirk and Rae had spoken of his innocence in the face of Dr Livingstone’s charges, although nobody dared stand up to him against the Livingstone brothers. All he had in his possession when they reached Cape Town was a canvas bag with a couple of shirts, two pairs of trousers and some sketching paper and pencils.

Baines received no mercy from John Washington and the Colonial Office, perhaps fearful of Dr Livingstone’s public reputation. However Washington seemed to have forgotten that he wrote in support of Baines’ request two years before for a salary increase from £200 to £300 that Baines: “was a really serviceable person” with “ten years’ experience in Africa” and brought “high testimonials from the late Australian Expedition.”

In the Cape the reaction was different; he was guest at a banquet given by his friend Henry Hall who gave a highly complementary speech as did Sir Thomas Maclear, His Majesty’s Astronomer. He was well-cared for by Frederick Logier and his wife…Baines later named the camp on the Baines-Chapman Expedition to the Zambezi after Logier. Baines wrote to Richard Thornton’s brother that he when he next met Dr Livingstone on the Zambezi he would thank him: “for the many expressions of goodwill his treatment of him had been the means of bringing out.”

Baines’ success

Baines contribution to the Zambezi Expedition was immense. Even leaving aside his practical skills his artistic contribution was a triumph. His oils, watercolours and sketches show the whole range of landscapes, natural history illustrations, portraits and action scenes that the expedition encountered in a much more dramatic way than the photography of the day allowed. Indeed, it appears that only Kirk’s photographs survived; there is little or nothing to show of Charles Livingstone’s photographs.

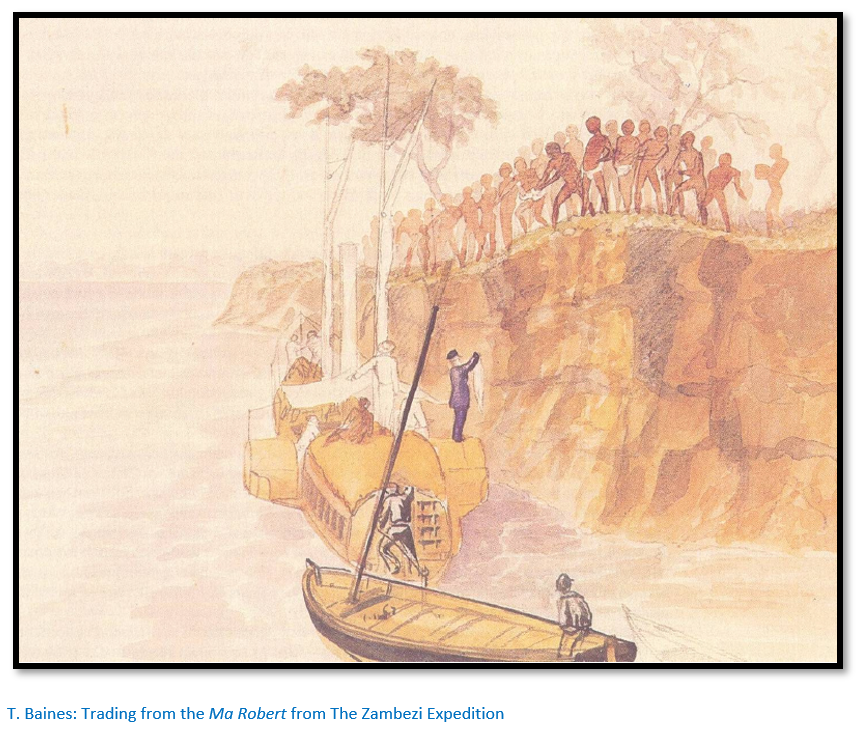

Dritsas says the paintings of the Ma Robert steaming up the Zambezi (most probably drawn when the vessel was stuck on a shoal) falsely provided a symbol of ‘the expedition’[ix] and represented a small outpost of the British Isles for viewers in the most remote of places.

Dritsas also makes the point that Baines images always show the exhibition members at work using their sextants, camera or engaged in mapping or botanical studies. For example the painting of the Pandanus palm seen in the article Thomas Baines’ disastrous 1858-9 Zambezi Expedition with David Livingstone under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com shows Baines sketching, Kirk cuts a nearby tree for specimens and the local guide stands for scale. Dritsas continues that although as humans they appear small against the abundant tropical vegetation, the implication is that by recording and learning they will control the wilderness.[x]

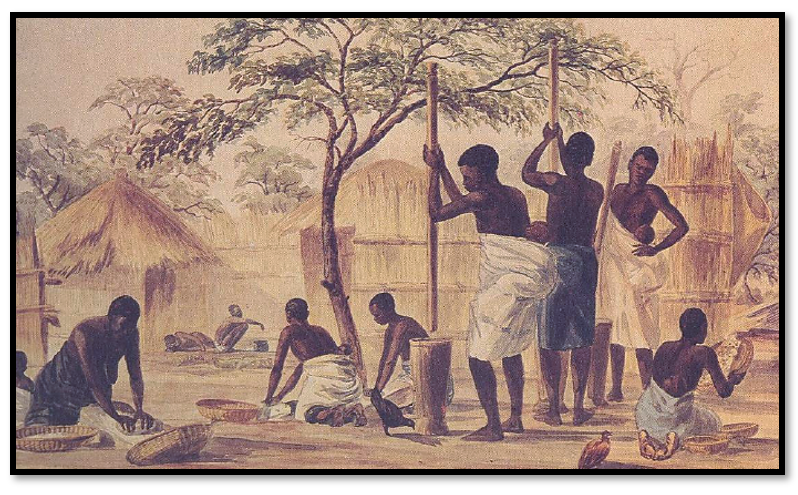

Dritsas also states that Baines’ depictions of a local sugar mill shown above are instructive but are also a studied fabrication showing all the process of sugar manufacture in a watercolour from cutting the cane to squeezing out the sap, boiling the sap and in another image making panellas or storage pots for the sugar. As well as being works of art they are also works of ethnography and economic botany.[xi]

In the watercolour of African women grinding millet Baines offers himself as the compound eye so that the viewer can see at once the separate but linked processes within the village scene. Dritsas says this the power of the travelled explorer with Baines bringing all his years of experiences together in a small space for the Victorian reader and viewer.

In addition, Dritsas says that Baines portraits of individuals, such as: Conde – a native of Tete, Shibante, a native of Mazaro, boatman and pilot, Mantlanyane and the two former slave women thy are all portrayed as individuals with personality, identity and respect for the subjects.[xii]

His paintings of the Roman Catholic Easter service at Tete and the joyous wedding celebration with altar boys in cassocks and wedding guests in top hats somewhat undermine the notion that the expedition is in ‘darkest Africa’ but reflect the reality of the Portuguese presence at Tete.[xiii]

References

L.S. Dritsas. The Zambezi Expedition 1858-64; African Nature in the British Scientific Metropolis. University of Edinburgh, 2005

D. Livingstone. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. Project Gutenberg eBook

J.P.R. Wallis. Thomas Baines; his life and explorations in South Africa, Rhodesia and Australia. A.A. Balkema, Cape Town 1976

J.P.R. Wallis (Ed) The Zambezi Expedition of David Livingstone 1858-63. Volume 1 Journals. Chatto and Windus Ltd. London, 1956

[i] The Zambezi Expedition 1858-64, P52

[ii] Thomas Baines, P91

[iii] Ibid, P97

[iv] Ibid, P103

[v] W. Cope Devereux, A Cruise of the Gorgon, P219

[vi] Thomas Baines, P105

[vii] Ibid, P111

[viii] Ibid, P114

[ix] The Zambezi Expedition 1858-64, P111

[x] Ibid, P113

[xi] Ibid, P114

[xii] Ibid, P114

[xiii] Ibid, P115