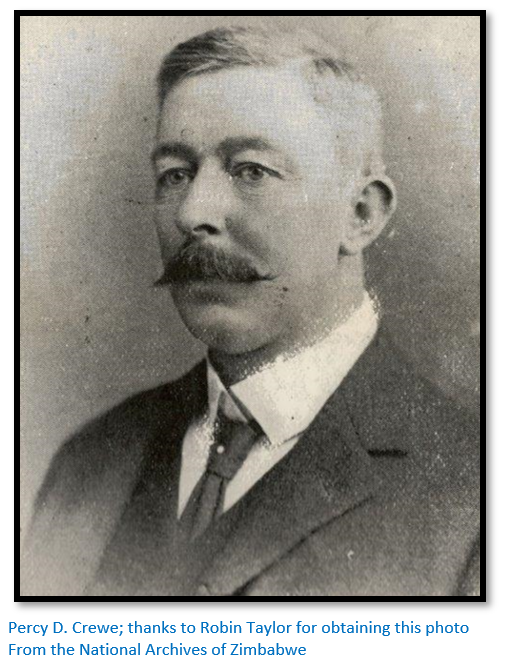

Reminiscences of Percy Durban Crewe of Nantwich Ranch, Hwange

GPS reference for Nantwich Homestead and Percy Crewe’s grave: 18°35´46.72"S 25°54´11.28"E

Introduction

The notes below are from the handwritten reminiscences of Percy Crewe (1862 – 1931) jotted down before he died. I have used the type-written notes done about 1939 by Foster Windram, who worked as a journalist for the Bulawayo Chronicle, as my source. There are few first-hand accounts of life at Bulawayo under King Lobengula in 1891 – 3; Crewe’s reminiscences were used by Oliver Ransford in his article “White Man’s Camp, Bulawayo” in the 1968 Rhodesiana Publication No 18, but have never been quoted in full. This article attempts to remedy this omission.

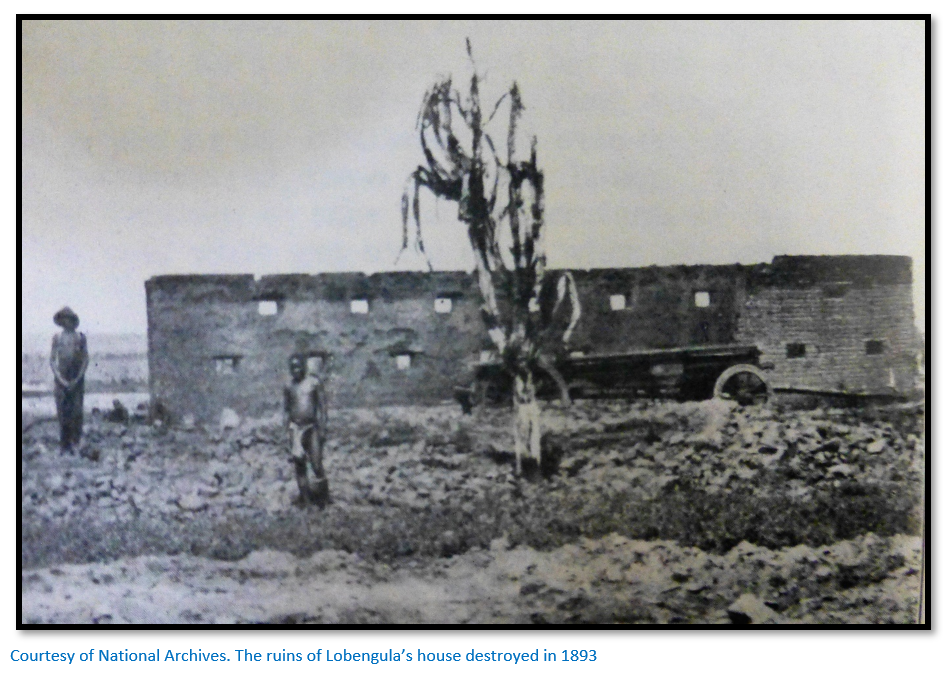

There is a detailed and sympathetic description of King Lobengula who protected the European residents in Gubulawayo when they might easily have been massacred and Crewe says the cruel image of Lobengula was largely conjured up by the missionaries for their own purposes. Crewe was one of the few remaining European traders in Bulawayo at the time of the Victoria incident which triggered the 1893 invasion of Matabeleland and he removed the guns given by the British South Africa Company in exchange for the Rudd Concession from Dawson’s store for distribution to the amaNdebele impi’s.

Crewe was asked by Lobengula to take charge of a deputation of amaNdebele to travel to England and lay his case before Queen Victoria. They were deliberately hindered and delayed by the Cape administration but got as far as Cape Town before being stopped by Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner and returning.

Percy Crewe is one of the figures in the background omitted in most historical accounts. Edward Tabler does not include him as he was not one of the pre-1880 hunters and traders; Robert Cary and Adrian Darter exclude him because he was not a member of the 1890 Pioneer Corps or the British South Africa Company’s Police and he did not take part in the 1893 invasion of Matabeleland, although his two brothers Fred and Harry did join the Salisbury column.

Background

Percy was eighteen years old when the Zulu War broke out; his parents Samuel and Ellen refused to let him join the Natal Volunteers, but after Isandlwana on 22 January 1879, he joined the Durban Mounted Reserve without telling anyone and after a week of training left for Verulam, a town twenty-seven kilometres north of Durban in KwaZulu-Natal. There was fear of a general uprising and “Durban was turned into a fortified camp, all the principal buildings being loop holed and barricaded with sandbags.” After a few months without any notable incidents, he and the Troop were recalled to Durban and disbanded. Napoléon, Prince Imperial was killed in a Zulu ambush on 1 June 1879 and Crewe describes his body “in the small old Roman Catholic Chapel in West Street. I was one of those who passed the coffin and followed the funeral procession to the Point next day.” [there is a photo of the Prince Imperial’s grave at Itelezi in the article Major Stabb’s hunting trip in 1875 to the Zambesi Valley via Gubulawayo under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

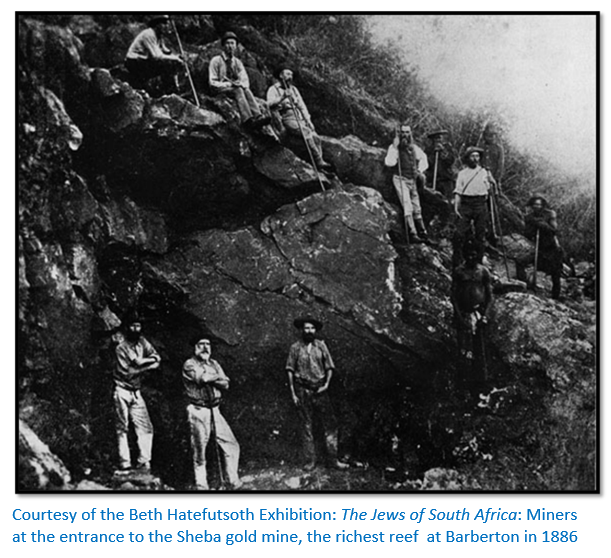

In June 1886 the young Crewe and his brothers Harry and Fred left Durban for the Barberton Gold Fields via Delagoa Bay (now Maputo) with a companion named Moodie. They went up the coast in an old tugboat, the Lion, and slept on coal sacks on deck. “Delagoa was an old-fashioned hole in those days, with mud walls around it and old guns mounted in bastions. Gungunhana’s people[1] had besieged them not many years before and Portuguese authority did not extend far beyond the walls. We were fortunate enough to strike a man called Woodhouse who had come down from Barberton with a wagon and oxen and he took us up via Spitzkop, on Pettigrew’s road.” [2]

The Barberton Gold Fields

He describes one of the characters they met as “Mad” Owen at the Komati Drift on the old Delagoa Bay road who had opened a wayside hotel on the Transvaal side of the River. In Percy Crewe’s own words: “Owen’s first remark was, have a drink, to which we naturally agreed. We had several more, but Owen refused to take any money. We naturally remonstrated, pointing out he could not run a wayside place on those lines. His reply was, I’ve bought all the stuff on tick on the other side of the river and no one can touch me. I think the man he did down was a Parsee named Dhoralji Dhunjeboy who was an arrogant rogue and well deserved it. I bought Vino Tinto [red wine] from him once on the same drift and it was well doctored with arrack.”

“Prospecting down the Crocodile River we struck a grave which had been dug up by hyenas and jackals. The skull and bones were lying on the ground, so we collected and reburied them, putting up a notice on a tree that the remains of an unknown white man were buried there. We found out afterwards that the remains were those a Hottentot boy [San Khoikhoi] working for Allan Wilson [killed on 4 December 1893 on the Shangani River, Matabeleland] who with I.M. Macaulay was camped on the Malalaine range not far off. A lot of old Rhodesians were in Barberton in the early days – Tom Meikle, I. Beesley, G.M. Isaac, A. Giese, H.I. Taylor and A. Boggie to mention a few. I have seen three big gold rushes; Barberton, Johannesburg and Rhodesia, but I have never seen a finer lot of men than were collected in Barberton in 1886, nor a crowd who knew less about gold-mining. Companies were floated and five or ten-stamp mills ordered with barely a pick put in the ground and even had the gold chutes proved longer than they did and maintained their richness, the rates of transport were so high and everything necessarily so expensive that very few could have been made to pay. However, the collapse came before most of them even made the attempt.”[3] [Fred Barber was also at the early days of Barberton and his story is described in Frederick “Freddy” Hugh Barber, hunter, trader, artist – visited the Falls in 1875 and Matabeleland in 1877 under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

“The Rand[4] killed off Barberton before it had a chance of showing what it was made of. I was a good walker in those days and thought nothing of doing thirty miles a day. I twice walked from Barberton to the Devils Kantor in a day.[5]This was over forty miles with a very stiff climb at the end from the Kaap Valley to the Kantoor. An old digger, one of the old alluvial crowd, had the only hotel there, on the first occasion I slept there…There were a good many cases of salting in the early days of Barberton. I think the Big Ben was the most flagrant of the lot. This property was pegged on the Makhonjwa range, there was a big cliff all of which was supposed to carry gold. It was pegged by a deviant cavalry officer who had been broken[6] in India and drank like a fish. How he did it I don’t think anyone ever found out, but there were always good pannings. The property was floated, I think, in Kimberley and shares went to a premium before the fraud was discovered. Our friend the Captain decamped one day, and it was then discovered that there was no gold whatever in the reef. Samples were taken very carelessly in those days and any clever rogue had a chance of selling.”[7]

The Witwatersrand gold rush

“I was first in Johannesburg in December 1888. Heights Hotel in Commissioner Street was the fashionable hotel of the place and there were three or four relays at each meal. I met a lot of Barberton and Natal men there.

I was on the Wanderers Ground[8] the day Paul Kruger made his celebrated speech. It was the first and only time I ever saw the President. I had managed to get onto the stand and was within a close distance of him. I shall never forget the ungainly figure in the badly fitting frock coat and pot hat. The crowd below was simply uproarious and every time the President tried to speak they sang God Save the Queen. It certainly was not cricket and I don’t wonder at the old man getting wild. He eventually made his speech to the reporters. That night I joined the crowd around who had collected around Captain von Brandis house. There was a guard of police around the house, but the crowd was very unruly, and the fence was smashed down…the crowd was yelling they would pull Oom Paul out. Next day the flag was pulled down and destroyed outside the Post Office and I know a man whose little girl had a dolls dress made from one of the fragments…”

Travelling to Matabeleland in 1891 was no picnic

“I arrived in Rhodesia[9] at the end of 1891. It was a tedious journey in those days. I walked from Barberton to the railhead which was then down the Crocodile Valley near the Figaro reef and from there I took the train to Delagoa Bay from where I travelled by sea to Port Elizabeth and from there by rail to Vryburg which was then the railway terminus. There was a weekly coach from there to Palapye run with trotting oxen, but I just missed this and had to spend a week in Vryburg which was one of the most God forsaken holes I was ever in. After a few days in Palapye I was fortunate enough to strike a wagon going to Tati[10] only to find on my arrival there that Marmon’s wagon had left for Bulawayo the day before. However, the manager (my old friend) Farley inspanned his mule cart and sent me up after them and I caught them just beyond the Ramaquabane[11] and from there had an uneventful trip to Bulawayo. I may say that in those day no white man was allowed to go past Tuli without Lobengula’s consent. This had been obtained for me previous to my arrival there.”[12]

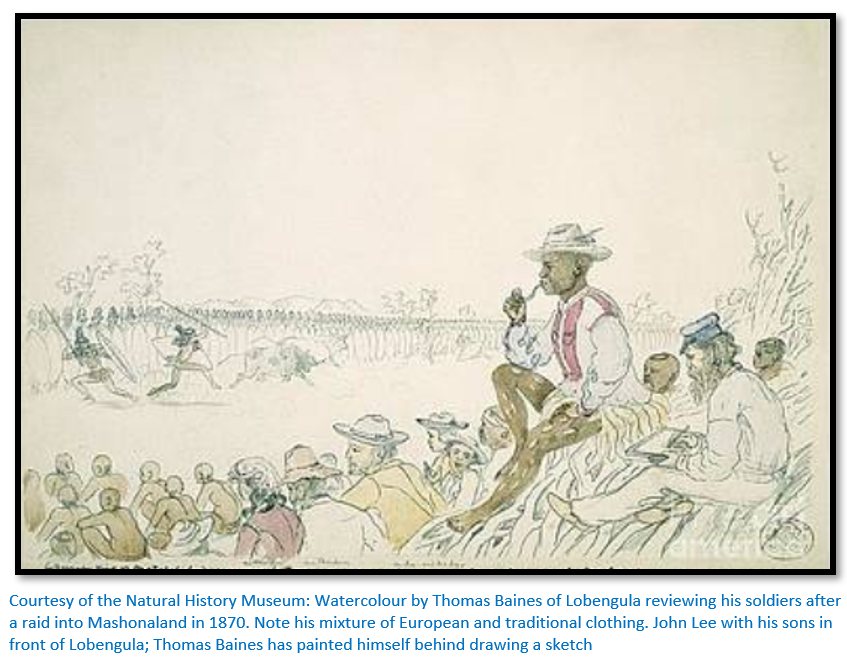

Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele[13] impressed Crewe with his presence

The first time I saw Lobengula he was dressed in a top hat, a pair of galoshes,[14] and the usual ‘mootja’ of skins around his loins. This was one of the very rare occasions on which I saw him wear any European clothing. As a rule, he was simply dressed in a ‘mootja,’ or skin girdle, with very often a kaross thrown over his shoulders in cold weather. I have been told by old hands in the country that in his younger days he wore coat, shirt and trouser, but that after he was made King he entirely discarded all European dress, principally, I believe, in deference to the opinion of his people. I saw him several times in the same old top hat, the galoshes I believe he wore on Dr Jameson’s recommendation as a protection against rheumatism from which he used to suffer in the cold weather. Lobengula stood over six feet in height I should say, and this enabled him to carry his huge proportion without appearing ungainly. He had what with us would be called a cultured voice which even today will be noticed among the high-bred Matabele, his features were good, the nose inclined to be aquiline and there was an undoubted air of command about him. In fact, none could have mistaken him for anything but a King or big Chief, a man accustomed to command.

Lobengula’s wives

Lobengula was an early riser, he always slept in a wagon. This wagon was drawn into the ‘Segodhlo’ or royal harem and after sundown no man was allowed within this enclosure, but the King’s slave boys, ‘bovane’ or ‘weevils,’ who slept around the fires in the open and whose ages ranged from three or four years old to twelve or fourteen years. He had about a hundred wives and I saw eighty of them dancing in one long string at one of the big dances, but as a rule he never had more than half a dozen or so with him at one time, the remainder being stationed at the various military kraals throughout the country. Sometime before my arrival in Bulawayo, he took two wives from Gaza country[15] relations of Gungunhana and had either of these Queens borne him a son he would have been recognized as heir to the throne, but he never had any children by these wives.

Loskey was his favourite wife[16] when I came into the country and she was also childless. Every year the Matabele unmarried girls (pure-bred Matabele only) came up during the winter by the hundreds and danced before the King; each girl carried a small grass broom and it was a very pretty sight; the idea being that the King should pick any girls he favoured for wives. I heard of several cases of girls refusing to go into the royal harem and I do not think they were punished in any way. For a native King, Lobengula was not a cruel man and the stories mostly cooked up by the missionaries of the atrocities committed by him are greatly exaggerated. He was guided very largely by public opinion in his executions; very often refusing to kill a man until such time that he could no longer refuse the public clamour. Death or banishment were the only two punishments. There were certainly a few cases of mutilation, but these were rare. As Lobengula himself once said, I have no prisons to put people in, I must kill them.

Festival of the Incwala or First Fruits

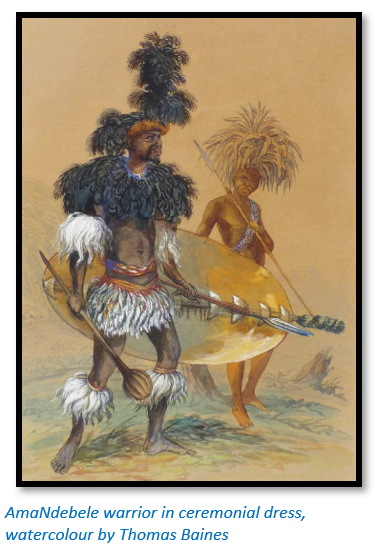

I was present at two of the big annual dances of the Matabele, inquala or feast of the first fruits in 1892 and 1893 and it was a very fine sight. Sometime before the time fixed for the dance every regiment sent slaves up to Bulawayo who built rough shelters outside the kraal and on the side from which the regiment was coming. The whole regular military force of the country was gathered at Bulawayo for these dances and there must have been from fifteen to twenty thousand warriors present. They filed in by regiments in a kind of regular formation of columns and formed up in an immense semi-circle in front of the King, the different regiments being distinguished by the colour of their shields. All wore the black ostrich feather headdress and cape, but the ringed regiments had the headdress thrown back on the shoulders leaving the head bare and with the ring they wore a crane’s plume. No arms were carried, only sticks.

The dancing commenced in the early morning and continued without intermission until the King appeared after lunch. No sooner had he taken up his position on a big chair, surrounded by some of his principal indunas, then a signal was given and the whole body made a wild rush towards the King, the idea being who could get there first and fall at his feet and woe betide the hapless individual who happened to get in the way. It was an imposing sight to see such an immense body of men running frantically forward shouting, jumping and yelling. We white people took care to be well behind the King when the rush came; after this there was more dancing and then the King led out the Imbezu regiment (the royal bodyguard) through one of the gates of the kraal and threw an assegai in the direction in which his enemies were supposed to be.

The whites as a rule were not supposed to see this performance. The King then led the regiment back and it was a fine sight to see the old King dancing in a very dignified way in front of them. They were a fine body of men and looked very big in their black ostrich feather capes and plumes. They were the only regiment who really made a fight for it at Bembese in 1893. Towards sundown a number of black cattle were driven into the open space between the King and the army and the regiment immediately broke up and chased them all over the place. The did not kill them, the idea being to catch and hold them. An enormous number of cattle were killed that night or the next day, the meat being distributed among the regiments who also now drank the beer which had been brought in several days previously by the womenfolk, but which they were not allowed to touch until the last day of the dance; as a rule, it was pretty sour by then.

The King was always most hospitable, and we always had more beef and beer at the big dance than we could possibly consume. None of the women, children or slaves were permitted to see the dance except the population of the town of Bulawayo itself and they were kept in order by a kind of police who walked around armed with thorn branches, which were used mercilessly on the backs of either men, women or children who got in the way. Lobengula’s Queens however attended the dance and danced in front of him in a separate body on this occasion. They were all dressed in yellow limbo with a profusion of pink beads and blue ivy feathers on the head. I counted eighty of them at the last dance I saw. We white people were always glad when the whole affair was over, and the regiments had returned to their districts as we had to put up with a lot of insolence from the younger men. I had my pipe pulled out of my mouth, and my hat knocked off by a noisy crowd of young men at the last dance in 1893 and they hustled me a lot before I could get away from them.

Crewe thought that stories of Lobengula’s treasure were a myth

There has been a lot of nonsense talked and written about Lobengula’s treasure. The Chartered Company[17] paid him £100 per month from the date of the granting of the [Rudd] concession and the Tati Company paid a yearly rental. I forget the amount, but it did not amount to more than a few hundred per annum, but from this he bought every year a certain number of salted horses[18] for cash. When I went down country in 1893 he gave me £500 to pay expenses and he sent several hundred pounds as a peace offering after his flight from Bulawayo. This money was intercepted by some of the Bechuanaland Border Police, then stationed at Inyati and never reached its destination. If it had there would probably have been no massacre of Allan Wilson’s party. Lobengula had no other sources of income and I do not think that at the time of his flight from Bulawayo he can have had more than £3,000 in cash, if that. He may have had diamonds[19], but I never heard of any. Lobengula’s wealth, like that of every other native King lay in his flocks and herds. Ivory of course had been plentiful, but at the time I came into the country it was scarce, and I do not think one thousand pounds[20] was brought to the King in a year.

Umvutcha the King’s favourite kraal

Lobengula’s favourite residence during the last few years of his life was at Umvutjwa, [Umvutcha] a kraal situated a mile and a half north east of the Umgusa River, opposite the Umgusa Hotel. This was a comparatively small kraal and had no regiment attached to it; in fact, it was a private residence of the King. When he was in residence there, the Indunas of the various districts lived in rough shelters put up outside the kraal on the side to which their districts lay. Any people coming in from the outside districts with a case to lay before the King went first to the Induna representing their district who then introduced the case to the King. Each outside district had a resident at the court to represent their interests.

It is difficult for people today to realise what the Matabele were when I first came into the country as with the exception of hunters, traders and missionaries they had never come into contact with white people and in 1890 held the ideas of Shaka’s Zulu’s of 1820. Very few of the real Matabele had ever left the country though a lot of the conquered people[21] had found their way down to Kimberley and had worked there for guns. The pure-bred Matabele had never intermarried to any extent with the conquered people and constituted the ruling class or aristocracy who held themselves to be the equals of any white man. This was bad enough and hard to stand, but what made it worse was that the slaves or conquered people [Maholi] who formed the bulk of the population adopted the same standpoint and as a rule were more insolent to whites than their masters. There is no doubt about the attitude adopted by these people towards Europeans and that they knew it – their whole attitude altered as if by magic after the occupation in 1893.

Events leading up to the Matabele War of 1893

Part of the purchase price given by the BSA Company to Lobengula for the [Rudd] mineral concession was one thousand Martini rifles[22] and one hundred thousand rounds of ammunition. As Lobengula repudiated the concession almost immediately after signing it, he refused to take delivery of these guns and ammunition and on my arrival in the country they were lying at Dawson’s store[23]. Just before the outbreak of the war in 1893 I happened to be alone at the store for a few days. One morning I was awakened very early by the head Induna of Bulawayo, Magwekwe, [Magwekwe Fuyana] who said he was sent by the King to fetch the guns. He had a small army with him. I set to work and opened up the cases and found that there was a bayonet for each gun. I had to show them how to fix these…one warrior got a pretty severe stab from one of his pals who was a bit clumsy.

Not long after the guns had been taken I got a message from the King to say that the number [of rifles] was not correct. This was a rather serious matter for me, so I rode over to Umvutjwa [Umvutcha] where the King then was. I told the King that I had counted the guns myself and that the number was correct. He replied that they were not all there; they have been counted and some are short. I then asked where they were, and he replied in the cattle kraal. I went there and found the rifles strewed about all over the place. I got hold of some of the Indunas and had the rifles placed in piles of ten and again reported to the King that they were correct. He then sent Mtjan [Mjaan] Induna of his Imbezu regiment to count them and I was very much relieved when I heard him report to the King that the number was correct.”

Consequences of the Victoria incident

“Lobengula never wanted to fight the British. Like Cetewayo [King Cetshwayo kaMapande 1826 – 1884] he was more or less forced into it by the younger men. There is no doubt that the Chartered Company very early after the occupation of Mashonaland saw that the position was untenable so long as the Matabele power remained unbroken on their border. The Matabele had for years been accustomed to make raids every winter into Mashonaland and after the occupation of Mashonaland by the BSA Company wandering parties continued the same game though no large expeditions were authorised by the King until the BSA Company sent letters to him complaining that the Mashonas were continually cutting the telegraph wire which then ran through hundreds of miles of uninhabited country from the Tuli River[24] to Salisbury [now Harare] Whether this was really done by Mashonas, or by wandering Matabele will never be known. At any rate Lobengula sent a fairly large impi under the command of an Induna named Umgandan to punish them and this led to the war of 1893 and the overthrow of the Matabele power.[25]

I knew Umgandan who a tall fine-looking pure-blooded Matabele standing over 6 feet and inclined to be very impudent to white people, he was a comparatively young man, in fact one of the young bloods who reckoned he was quite the equal of any white man. Had Lobengula sent an older and more experienced man in charge the chances are that the events which occurred at Victoria and which brought on the 1893 war would never have happened.

I was in Bulawayo when this impi started out and felt a foreboding at the time that something serious would happen. My two brothers, Harry and Fred, were both in Mashonaland and wrote me repeatedly to get out of the country as there was going to be a fight and Jimmy [James] Dawson got letters from Dr Jameson at the same time, advising, in fact ordering, all the white people in Matabeleland to clear out, but it was easier said than done; we had a lot at stake and events moved so quickly that while we considering the matter, the fat was in the fire. Personally, I had made up my mind to leave as soon as I could, but I did not care to make a bolt as Tainton[26] afterwards did when he got the news of the Victoria fight.

Just about this time a white man who was travelling with a wagon was brought into Bulawayo by the Matabele (I have forgotten his name) He had wandered over the Mashonaland border and was brought in under escort to Lobengula, who sent him to Colenbrander[27] to look after as he was very bad with fever. A few days after his arrival Colenbrander sent over to me to say he was dead and asked me to let him have one of the King’s gun cases for a coffin. I went over and had a look at him and could see no sign of life, he was as yellow as a guinea, and appeared to be dead, but was not stiff. From what I have seen since of malarial syncope or collapse I have often wondered whether we did not bury this poor chap alive as we nailed him down in the box while still limp. We buried him where Sauers town[28] now lies. I read the burial service and I remember Colenbrander saying over the grave: “Well, I expect this is the last white man who will get a decent burial in this country for some time.” Lobengula went for me afterwards for taking the gun case for a coffin without his permission.

When the first fight between the whites and Matabele took place at Victoria in 1893, I was in Bulawayo. We had seen the impi despatched by Lobengula and there was a general feeling throughout the country that something was going to happen. Lobengula sent this impi because the Chartered Company was continually complaining about the telegraph wires being cut[29] and the ostensible purpose was to punish the Mashonas for doing this, but the man put in charge was not at all the class of Matabele to be conciliatory to the whites with whom he was bound to come into contact. His name was Umgandan and I knew him well. He was a very fine specimen of a pure-blooded Matabele, standing over six feet and built to proportion, but he was a young man and had very little into contact with the whites and considered himself equal to any white man living. It was almost a foregone conclusion that he would be insolent to the white people he met, and I heard afterwards that in the interview he had with Dr Jameson at Victoria he spat on the ground in front of him; about as big a sign of contempt as he could possibly show. I believe he was the first man shot at Victoria. The news of the fight at Victoria was telegraphed to Palapye and from there mounted messengers were sent onto Bulawayo and we received the news a day before Lobengula did.

Tension in Bulawayo

The message was an urgent one for us to get away. We could do nothing. Flight was out of the question as we only had two horses among four of us[30] and when we asked Lobengula for permission to go, he refused, so we simply had to sit still and wait, and it was a pretty nervy time. Rees[31] was the only missionary in the country at the time. We sent a messenger out to him at once and he came in with his wife and child without delay and obtained permission from Lobengula to leave the country. He started next day and lost no time in getting out. I fancy the reason why Lobengula let him go was that he was such a miserable worm. Tainton, a very old hand in the country who was living at Bulawayo, no sooner heard the news from us than he inspanned his wagon and leaving everything behind, travelled day and night until he got to Tati.

The King was very wild with him and I remember his saying: “let him go, but he shall never come back.” The weeks that followed were about the most exciting that I ever spent. Feelings ran very high amongst the Matabele and I think we all felt that each day might be our last. When the impi from Victoria got back things got worse, as the natives then got to know exactly what had happened and it was quite a common thing for a native to put up his gun at you, full cock,[32] take a steady sight and tell you that he was going to shoot, calling you at the same time every name he could lay his tongue to. We got used to it after a few days and it made them wilder to see the contempt with which we treated them. I think our coolness had a good deal to do with saving our lives at the most critical time when the impi got back, but we undoubtably owed our lives to Lobengula. He had only to give a hint and we should have been wiped out as the people were simply thirsting for our blood.

I often wonder that no accident happened ‘to fire the mine,’ as we would have been an easy prey as we never carried arms. I remember well one day I had got up onto one of the wagons in the backyard to do something. There was a crowd as usual outside the fence and one covered me with an old blunderbuss and said he was going to shoot. I watched him out of the corner of my eye and he certainly looked as if he meant it, as he was half-drunk, but one of his pals evidently thought so too, for he grabbed the gun and how it was that it did not go off in the struggle that ensued was always a marvel to me. I finished what I was doing and took no notice, but I know I was glad to get out of such an exposed position. I remember that Dawson was very wild with me for taking a rifle and twenty rounds of Lobengula’s ammunition into my bedroom. I told him that I did not mind going about with the rest of them unarmed during the day, but that if they came to blot us out at night I was going to ‘have a show for my money.’ The reason we went about unarmed was that we thought we had a better chance if we showed we were not afraid.

After about a fortnight Lobengula gave permission for us to leave the country but said that if we went we should never be allowed to come back. That evening Dawson, Fairbairn, Grant and I worked nearly all night loading up the wagons; we put on all the most valuable stuff, we only had two wagons, and could only load up a very small portion of the goods we had. The arrangement was that Fairbairn, Grant and I were to start at daybreak with the wagons and Dawson was to ride over and say goodbye to the King. Late as it was when we went to bed, I was up at the first streak of dawn and went into Dawson’s rooms to wake him. He was a rather sarcastic person and said: “you needn’t worry about getting up.” I said: “what is the matter?” He said: “Magwikue[33] and some Indunas came down from the King during the night and told me we could not leave.”

I remember thinking at the time that he might have let me know at the time they came, knowing how anxious we all were, however he kept it to himself until next morning and never told any of us. Fairbairn and I took it fairly philosophically, but poor old Grant got very excited and walked up and down saying: “I know we shall all be killed.” Poor Grant, he had made a bolt from Bulawayo some years before in the days of excitement over a concession and Lobengula had sent an impi to bring him back. When Grant saw them coming, he, so the story went, got into the wagon box thinking they had come to kill him. He was hauled out and taken back to the King and it was always a joke against him afterwards. He was murdered by the Mashonas in the 1896 Rebellion. As Lobengula refused to let him go, Dawson obtained permission for Grant to take some cattle through to Salisbury and this the King agreed to. Grant left soon after and got through safely to Mashonaland.[34]

On 20 August 1893 Crewe is sent with an amaNdebele deputation to Cape Town to make Lobengula’s case against the Chartered Company (The peace mission)

It must have been nearly a month after the events at Victoria that Dawson came back one day from paying a visit to the King and told us that Lobengula wanted me to go down country in charge of a deputation which he intended sending to England to lay his case before Queen Victoria. In case I agreed to go, I was to go over and see the King the next day. I need not say how delighted I was at the idea of a chance of getting out of the country and I rode over to Umvutcha early next morning. On the way I was stopped by a large body of armed Matabele who asked me where I was going. I said that the King had sent for me. They called me a dog and a few other fancy names and wanted to know when the white men were coming to fight them. “We will simply eat them up” they shouted. I told them they had better ask the King as I did not know, and after some more abuse and lots of threats as to what they were going to do, they let me go on.

I found Lobengula as usual friendly but looking very worried. He said: “I want you to take my people to the Queen. I said: “yes King, I will go, but the road is a long one and in the white man’s country the road costs money.” He said: “I know, how much do you want?” I said: “it will cost at least £1,000.” I may say that he told me that he intended sending three men. He struck at the £1,000; said it was altogether too much and offered £500. We haggled for some time, but I was so anxious to get out of the country, that I accepted his terms. As a matter of fact, I would have gone without any payment from him at all. This matter being settled, the principal Indunas were called together a few days afterwards to hear the King’s word and the white men in the country [i.e. in Bulawayo] were also summoned to be present and witness what the King had written.

A Fingo native[35], John Makunga[36], wrote the letter at Lobengula’s dictation and he afterwards gave me the rough draft of the letter to Queen Victoria[37]. This I gave to Mr Rhodes many years afterwards. It set forth Lobengula’s case very ably, that he had never granted a concession, that the white people had come into the country against his wish, and that when he had sent an impi to punish the wrongdoers in Mashonaland at the white people’s request, they (the whites) had set on and killed his people, and much more to the same effect, ending up by affirming his loyalty to the Queen and a wish for peace. Poor old Lobengula, he only wished to die in peace.

I left Bulawayo on 20th August 1893. The chief man of the party was a pure-blooded Matabele named M’tjete [Umshete] who had previously been to England. He was one of the two Matabele Indunas[38] taken home [i.e. to England in 1889] by Maund and Colenbrander and it was very interesting to listen to his experiences. [See also the article Why Lobengula sent envoys to Queen Victoria in the late nineteenth century under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] They had an audience with Queen Victoria at Windsor. I remember asking M’tjete what he thought of the Queen. “She is small, but she looked very big” was his reply and what struck him most was that when the Queen walked forward, the others walked backwards in front of her.

The other members of the party were James M’Kizu, a Zulu who spoke and understood a certain amount of English and who had been in Matabeleland a long time and John Makunga, the man who had written the letters. The latter wrote and spoke English and was interpreter to the party. Lobengula gave us a spring travelling wagon and ten oxen. I must say that when I said goodbye to Dawson, Fairbairn[39] and Usher I felt sad at heart. Lobengula had stated that he was going to hold them more or less a hostage for my return and I promised them when I shook hands that I would come back whatever happened, and I meant it, but it was a sad parting and I very much doubted if I should ever see any of them again. Colenbrander was also there with his wife when I left. He was agent for the Chartered Company and though he was anxious to get out of the country, the King would not let him go. He got away very cleverly in the end. There were a lot of smooth-bore muskets lying at Palapye for Lobengula. They had arrived there just as the troubles begun and the Imperial Government had refused to let them come on. Lobengula was very anxious to get these guns and Colenbrander persuaded the King that if he let him go down with a wagon and oxen he would get them released and bring them up. Eventually the King agreed to this and that is how Colenbrander and his wife got out of the country.

James Dawson takes peace envoys to Tati

When Gould Adams column[40] arrived at Tati Lobengula got anxious and not having heard anything definite from my mission, he sent Dawson down there with another mission consisting of his brother N’CubuN’Gubu,[41] Mantus, Induna of Mabugutwani and another whose name I forget. Dawson arrived safely at Tati with these men, but while he was having a talk with Selous, whom he had not seen for some years, his envoys were arrested and put in the guard tent. Two of them, Mantus and the other man, made a dash for liberty, grabbing a bayonet from one of the guards. They were promptly shot. The King’s brother sat still and was not harmed. It was an unfortunate affair and might easily have resulted in the death of Fairbairn and Usher who were still in Bulawayo. This was another example of Lobengula’s forbearance. It was often thrown up in our teeth afterwards that we white men murdered ambassadors who were sent on a peaceful mission and there is no doubt that if the country had not been in such a turmoil at the time that more would have been heard about it.

The columns move on Bulawayo

Fairbairn and Usher were now the only two white men left in Matabeleland. Lobengula protected them until his flight after the fight at Bembese.[42] He sent them a message to say that he could no longer be responsible for their safety and advising them to go to their own people. They heard sounds of firing in the distance and had got onto the roof of the only brick building in the compound. This roof was iron, and they thought less likely to burn. They had taken up rifles and ammunition and were prepared to sell their lives as dearly as they could. A patrol from the column under Borrow[43] got in about 8 o’clock that night and found them playing poker on the roof.[44] He [Borrow] undoubtedly saved their lives as we found out afterwards from native sources that there was a plot to loot and burn the store that night and of course, to murder them.[45]

It must have been a trying time sitting on that roof, watching the great Bulawayo kraal burning and expecting every moment could be their last. Poor Fairbairn[46], kind-hearted gentleman, he had no enemy but himself. He was made quarter-master of the BBP[47] after the occupation and died and was buried at Inyati a few months afterwards. He together with Leask had been granted a concession[48] by Lobengula year before the Chartered Company came into the field. Leask, I believe, got a pension from the Chartered Company, but Fairbairn had signed his name as a witness to some document repudiating the Charter concession and Rhodes never forgave him, so he got nothing.

Crewe takes a Matabele peace mission to Cape Town (the peace mission, continued)

On leaving Bulawayo I lost six of the oxen at the first outspan at Khami River, but I was so anxious to get out of the country that I trekked on with four oxen and the missing cattle did not catch me up until I was through the Mangwe Pass. I found Tati armed to the teeth and full of rumours of Matabele impis on the way down to “eat them up” and they were rather astonished when I told them how comparatively peaceful the country was. On arriving at Palapye I immediately reported myself to Mr Moffat[49], the British resident, and delivered him Lobengula’s letter. It was Mr Moffat’s father[50] who had told Umziligas [Mzilikazi] Lobengula’s father of the fine country to the north of the Limpopo and the Matabele’s always had a great liking and respect for him. I raised the question of expenses with Mr Moffat and he said he would wire at once to the High Commissioner at Cape Town and ascertain what was to be done. This he did and next day informed me that we were to go forward to Cape Town and that the Imperial government would pay all expenses. On arrival at Palapye I wired at once to my brothers in Salisbury [Harare] letting them know that I had got out of Matabeleland. They replied asking me to come up at once to Salisbury to join the column which was then being formed to conquer Matabeleland. Of course, it was out of the question, but I think if it had not been for the thought of the white men I had left behind in Bulawayo, I should have gone up.

We left Palapye by the first mail coach (drawn by oxen) which left after our arrival. We got down as far as Mafeking when M’tjete got very ill with dysentery and we were delayed about a week. On arrival in Cape Town we were met by a messenger from Government House and taken to Poole’s Hotel which was then the leading hotel in Cape Town and we stayed down there for about a fortnight at government expense, having interviews nearly every day with the High Commissioner, Sir Henry Loch, who had wired to London advising the government there of our arrival and asking whether we were to proceed to England.

Meeting with Sir Henry Loch [51]

In the meantime, events were moving rapidly in Matabeleland and one morning the High Commissioner told M’tjete that he had very serious news. Tell M’tjete, he said to Johnnie [James] Makunga that the Matabele have fired on the Queen’s troops. This referred to a patrol of the BBP who were reported to have been fired on near the Tuli River. It became well-known afterwards that that they never had been fired on, but the NCO in charge got a commission for bringing in the news. M’tjete’s answer to HE [His excellency] was straight and to the point. He said: “it’s a lie.” However, by this time Dr Jameson was over the border and a day or so after Sir Henry Loch went for me and said he could not send us to England and was… [missing line] …in Cape Town. I said: “well sir, we will go back, I suppose you will pay expenses?” He said: “Yes, we will pay expenses back to Palapye; when you get to Mafeking put your account into the Civil Commissioner [CC] there and at Palapye, Mr Moffat will pay.”

I left Cape Town a day or after with my party after a very pleasant time. At Mafeking I put my account into the CC who said the liquor bill was too high.[52] I told him I was keeping M’tjete alive on port and champagne, but he still demurred, so I said I would not budge until I was paid. I waited for about a week, when he sent for me one morning and showed me a wire from the Imperial Secretary: “Please inform Mr Crewe that all expenses will be paid, including drinks.” I got it all and left by Cape cart for Palapye the next day; hiring two Cape carts, one for the natives and one for myself and Frank Wirsing who travelled up to Palapye with me. I got the balance of my expenses from Moffat.

On arrival at Palapye I heard there had been a big fight in Matabeleland and that my brother Fred had been killed; a day or so later I heard that he was only wounded in the leg. I left the natives at Palapye and they eventually all got back to Matabeleland. I bought a buggy and two horses and drove from Palapye to Macloutsie camp where I loaded up a couple of wagons with stores and I then… [line missing] …to Tati and from there to Bulawayo where I arrived just after Wilson’s party had been cut up on the Shangani. The road was hardly open, and I felt rather nervous as there were armed parties of natives wandering around.

Return to Bulawayo

I got through all right and found my brother Fred in hospital with a bullet wound in the leg. The bullet, a martini, had struck him on the shin and Dr Jameson took it out of the calf of his leg after the fight was over. This happened at Bembesi and it was a wonder he did not lose his leg.

I shall never forget my feelings when I saw a tattered old Union Jack flying over what had been Colenbrander’s store and was now Dr Jameson’s headquarters after putting up with the insolence of the Matabele for two years. It brought tears to one’s eyes to see the old flag flying once more. The most marvellous change of all was in the Matabele themselves. When I left the country four months before, they were full of brag and insolence, as if by magic this was now all changed, and they were now as civil as, in fact more so, than any down country native; the old swagger was quite gone, never to reappear.

Summary Biographies of the Crewe brothers; Fred, Percy and Harry

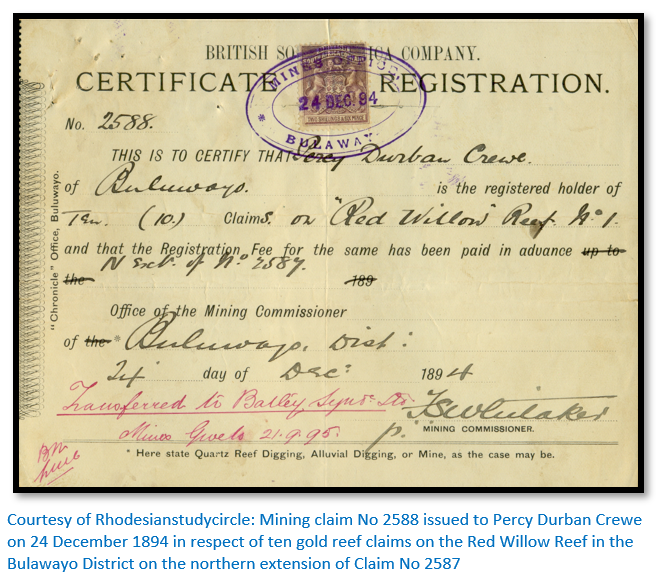

After the 1893 Matabele war the Crewe brothers and their Uncle Charles Acutt opened a business in Bulawayo trading as "Acutt & Crewe" dealing in land and mining rights. In 1896 when the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela began, the brothers all joined the Grey's Scouts, a unit formed by George Grey who owned several mine properties and narrowly escaped death at the start of the uprising.

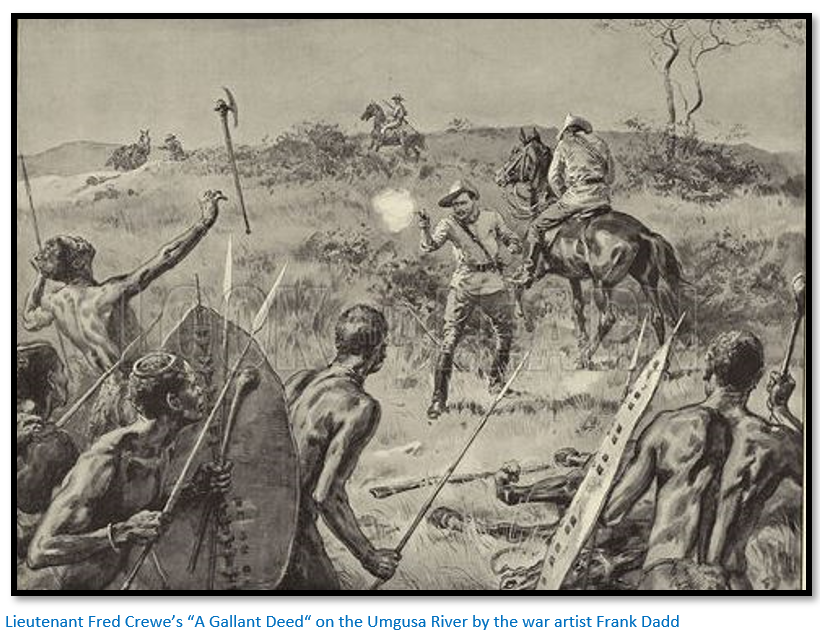

Fred Crewe’s gallantry

Fred Crewe was the hero of an incident as the Grey’s Scouts were holding off the Matabele whilst their own wounded were being withdrawn, when a fresh body of Matabele armed with assegais, knobkerries and some guns attacked them. Lieut. Blair Hook's horse was shot and fell, throwing its rider to the ground. F. C. Selous, writing of the incident in Sunshine and Shadow in Rhodesia, said "Hook got on his legs and was hobbling forward when Crewe said to him. Why don't you pick up your rifle? I can't: was the reply, I'm too badly wounded. Are you wounded, old chap? said Crewe, then take my horse and I will try to get out on foot." After helping Hook on to the horse Crewe drew his revolver, took careful aim, and shot the leading amaNdebele in the chest. The others advanced, throwing assegais and Fred Crewe backed away still firing at the leaders. The rest of the Grey's Scouts heard the shooting, rushed back and saved Hook and Crewe. Fred was recommended for the Victoria Cross and his comrades were surprised that he did not get it as he had already been mentioned in dispatches several times. Cecil Rhodes was so impressed by the story that he commissioned Frank Dadd to paint a watercolour of the incident and presented it to the Durban Art Gallery, where it remains but is not on display.

Fred was fatally wounded at Ramathlabana in the Boer War and died on 2 April 1900. Baden-Powell asked the Boers for his body and he was buried at Mafeking Cemetery.

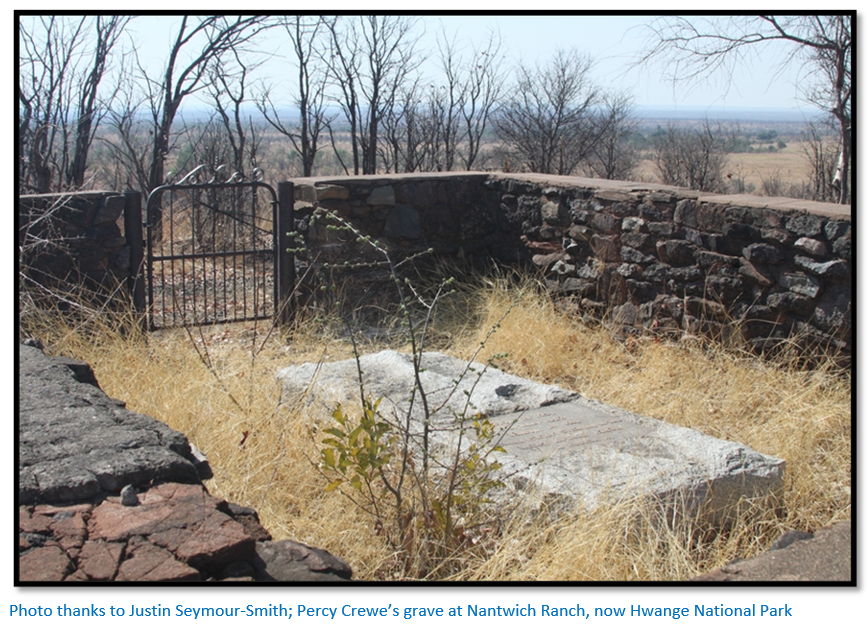

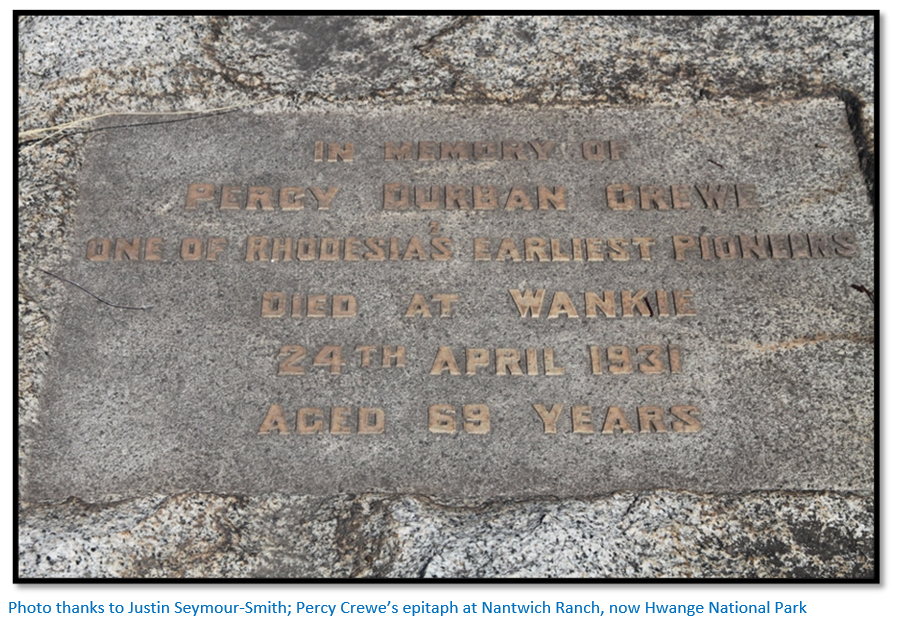

After the 1896 Matabele Rebellion or Umvukela in which he served as a sergeant, Percy Crewe, whose reminiscences are recounted above, became well-known locally in Matabeleland through prospecting and mining and as a broker of both land and native labour. He then worked for Albert Giese on a Deka farm, supplying beef to the Wankie [now Hwange] coal mine. Then he became a storekeeper, and finally a rancher, having bought 22,000 acres of land west of Hwange which he called Nantwich Ranch, which Gary Haynes calls a kind of geographic joke as Crewe and Nantwich are located near each other.[53] Nantwich was almost on the border with Botswana, but now forms part of Hwange National Park.

However like many of his time he continued the quest for gold; in 1909 he was prospecting a reef called “the Californian” in Matabeleland south, but like so many it turned out a disappointment and he was telling Albert Giese that he expected to be out of work and on the "bone of my arse again. You will probably hear of my tramping through the country shortly with a pack on my back and a tin Billy, accompanied by a black lady."[54]

Early experiments in growing sugar at Nantwich Ranch

Another of his ventures is described on a paper on the Development of the Sugar Industry in Rhodesia by C.L. Robertson that involved the first attempt to grow sugar cane on a commercial scale in Southern Rhodesia in 1927. After Crewe had grown small quantities of sugar cane on Nantwich Ranch he made a request for a Government lease of approximately 41,000 acres of land in the vicinity of Kezi Siding to grow commercial sugar cane. This was before Tom McDougall planted experimental plots of sugar cane on Triangle Ranch in 1931. Percy Crewe obtained financial backing from some of Natal’s prominent sugar industrialists, formed Crewe’s Rhodesia Sugar Estates Ltd and was granted a lease of the land on the 1st May 1928. The lease conditions were that a minimum of 300 acres should be planted to cane by the end of 1929 and increased to 1,058 acres by the end of 1931 but the plant cane had to be brought up from Natal, and only 150 acres had been planted by the end of 1929 and increased to 250 acres by the end of May 1930. With a further 1,100 acres of land cleared and ready for planting; the growing stand was reported as very promising. Unfortunately, during the 1930 winter a very severe frost destroyed more than half the cane, and the venture was abandoned after £10,000 had been spent on the project. Probably the venture was foredoomed to failure as no irrigation facilities were provided and there was too much risk of frost in the area.

Crewe’s fondness for a drink

Percy Crewe was a festive man, and well known for it with an earlier reference to “keeping M’tjete alive on port and champagne.” Gary Haynes in his book Hwange National Park: The Forest with a Desert Heart states that long-time acquaintance and fellow farmer in the Wankie District, H.G. Robins, felt that alcohol was the downfall for Percy Crewe. His long-time female companion, Vuvuka, was well-known for making strong traditional African beer. He lived at Nantwich until he died on 24 April 1931 and is buried there.

Haynes says: “He was affectionately remembered by Sir Robert Coryndon when Sir Robert was beginning his rise to political eminence in the colony of Rhodesia ("Good luck to P.D....he never sings Clementina' now I suppose ---alas!") but his personal character was too rough to merit the reverence that new Rhodesian colonists offered the first white men to have entered the "old man's [Rhodes'] country."[55]

Percy Crewe the family man

Gary Haynes says that from his late thirties Crewe was living with an amaNdebele woman named Vuvuka for “swollen” who lived at Nantwich farm when he was there and sometimes joined him when he was not. I am not sure if they had any children. These informal arrangements were not unusual at the time; Albert Giese had black mistresses as did Selous.

Harry Crewe was the only brother to marry. Harry and Margaret’s home was a group of huts about five miles from Bulawayo which was called Trenance, but which were burnt down during the Matabele Rebellion: later they built a brick house which still exists. After the birth of their two daughters they moved to Excelsior Mine near Umvuma, but sadly Dulcie died of pneumonia at the age of thirteen. During World War I Harry served in East Africa but was invalided out owing to malaria. After convalescence, he joined the African Labour Corps as an interpreter and was in France until the end of the War.

He returned to Rhodesia, but his wife never got over their daughter Dulcie's early death and developed nervous asthma and later heart trouble. Harry took the family to Durban where they lived until his wife died, but saddened by her long illness and death, Harry and his remaining daughter Ursula found it difficult to carry on. At Percy’s urging in 1926 they settled down with him at Nantwich Ranch on a ridge overlooking the Deka Plain. Ursula and the men lived a very active life patrolling the whole of the ranch's 22,000 acres bordered by the Deka River and Bechuanaland (now Botswana) frontier.[56]

J. McAdam records in his article ‘Birth of an Airline – Establishment of Rhodesian and Nyasaland Airways’ in Rhodesiana No 21 December 1969 that on 11 January 1928, a newly arrived De Havilland Moth aeroplane was chartered by Harry Crewe to fly him urgently to the Nantwich ranch. This was probably the first private charter aircraft flight in Rhodesian aviation history (apart from the Duc de Nemours' abortive 1927 attempt to fly to Plumtree).

After Percy Crewe's death, Ursula met Horace Vaughan-Evans at Wankie and they married at Victoria Falls on 7 December 1933 and then joined re-joined Harry at Nantwich where all three joined in the hard work of ranching. Harry died on 2 November 1937 six years after his brother Percy, Albert Giese died the next year and the last of the old-timers Herbert “Bert” Robins died in Wankie Hospital on 28 June 1939.

References

Y. Miller. Acutts in Africa. Privately published Pinetown 1978

Crewe, P.D. MSS. In Bulawayo Public Library

G. Haynes. Hwange National Park: The Forest with a Desert Heart. 2014

Memoirs of D.G. Gisborne; Occupation of Matabeleland, 1893. Rhodesiana Publication No. 18, July 1968 P.1-12

J. McAdam. Birth of an Airline – Establishment of Rhodesian and Nyasaland Airways. Rhodesiana No 21 December 1969, P36 – 50

O.N. Ransford. An historical sketch of Bulawayo. Rhodesiana Publication No. 16, July 1967 P.56-65

O.N. Ransford. White Man’s Camp, Bulawayo. Rhodesiana Publication No. 18, July 1968 P.13-21

C.L. Robertson OBE. Development of the Sugar Industry in Southern Rhodesia

F.C. Selous. Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1968

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd, Cape Town 1966

Rhodesiaheritage.blogspot.com/2013/10/whatever happened to May?

[1] Ngungunyana was a Shangaan King, a grandson of Shosangane defeated by Chaka Zulu in 1820, who came to the throne in 1884. The Portuguese attempted to undermine his authority by arming vassal tribes and in 1889 Ngungunyana countered by moving up to 100,000 of his tribe from Mount Selinda in Manicaland in Zimbabwe into Gazaland in Mozambique. Throughout his reign he continually played off Portuguese and then British interests; often called the Lion of Gaza and the last African King of Mozambique, he finally succumbed to the Portuguese military and was sent into exile in the Portuguese Azores where he died in 1906

[2] This is the same route that Sir Percy FitzPatrick travelled as a transport rider and drew on his experiences to write the classic children’s book, Jock of the Bushveld.

[3] Crewe would have been familiar with the Sheba Reef Gold Mining Company which continues to operate

[4] Small isolated outcrops bearing gold were discovered on Pardekraal Farm and the Jukskei River and the Kromdraai Mine operated to the north-west of Johannesburg as early as 1883, but the main reef that stretches from Johannesburg to Welkom was discovered by an itinerant prospector named George Harrison on the farm Langlaagte in July 1886. Harrison is believed to have sold his claim for less than ten pounds and vanished from history; but his find started the Witwatersrand gold rush.

[5] The name "Duiwels Kantoor" or "Devil's Waiting Room" came from the outcrop of strangely formed rocks said to look like monsters waiting for the devil

[6] Demotion in military rank

[7] The Sheba Mine began in 1885 and is still operating in 2018 – in the early days large investments were made and the first Stock Exchange opened in Barberton together with billiard saloons, music halls and hotels. But the boom lasted for only a brief period before most of the miners moved away to the newly discovered gold fields of the Witwatersrand

[8] The original Wanderers Grounds was replaced by Johannesburg’s Park Station in 1946

[9] Now Zimbabwe

[10] In late 1867, Karl Mauch and Henry Hartley, one of the most celebrated elephant hunters, went on an exploratory trip to Matabeleland and came across evidence of old gold workings between the Shashi and Ramaquabane rivers, which was subsequently christened the Tati district. Mauch rushed back to Potchefstroom to spread the word of his exciting discovery. European, American and Australian newspapers spread the news of Southern Africa’s first gold rush and many came to get rich including Thomas Baines who lead the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company and the London and Limpopo Mining Company led by Sir John Swinburne, who arrived at Tati in April 1869. In the end, the Tati goldfield produced only small amounts of gold; disappointment set in quickly and, when diamonds were discovered on the banks of the Vaal River, most of the diggers abandoned their claims and the site of the first gold rush.

[11] The Ramaquabane River (now the Ramoqueban) forms the western boundary to the Tati district and joins the Shashe River on the border of Zimbabwe - Botswana

[12] John Lee (1827 – 1915) actually Johannes Loedwickus, more Boer than English, arrived in Matabeleland about 1858 to hunt elephant in the Shashe and made his permanent camp at Mangwe where there was perennial water and where he built a house in 1866. His wife joined him but died in childbirth in 1870. Trusted by Mzilikazi and Lobengula, he was their customs officer in the following decades and all the travellers, hunters and missionaries stayed with him whilst waiting for permission to be “given the road” i.e. permission to enter Matabeleland. Sociable and a well-known teller of tall tales, he refused to serve under the BSA Company as a guide or interpreter in the 1893 war and had his Mangwe farms confiscated.

[13] I have used the term amaNdebele rather than Matabele

[14] Galoshes – rubber boots

[15] Modern day Gaza stretches from the Indian Ocean coast bordering South Africa to the west and Zimbabwe to the northwest; Inhambane province to the east

[16] Lozigeyi Dhlodhlo according to the website Bulawayo1872.com but sometimes spelt Lozikeyi

[17] British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSA Company or Chartered Company – all used interchangeably in the article)

[18] Horses that had suffered from trypanosomiasis or “sleeping sickness” but who had recovered from the sickness and were believed to have a measure of immunity.

[19] Believed smuggled out and brought back by workers on the Kimberley diamond fields when their contracts finished

[20] Equivalent to 454 kilograms

[21] The name of conquered people was Maholi

[22] Martini-Henry breech-loading rifles

[23] James Dawson the well-known trader in Bulawayo from 1884 – 1905 eventually had eleven stores based at Balla Balla, Fairview, Essexvale, Filabusi, Geelong Mine and Khami River. A trusted confidant of King Lobengula, he along with James Fairbairn, Harry Grant, William Usher, Armstrong and Johan and Mollie Colenbrander were resident in Bulawayo during the progress of the Pioneer Column through Mashonaland in August – September 1890. He married Allan Wilson’s fiancée May Manson Thomson from Garmouth in Scotland in October 1896 and amongst the wedding gifts was a cheque from Holloway prison where Dr L.S. Jameson and Sir John Willoughby were serving time for their part in the Jameson Raid.

[24] Tuli now Thuli River, a major tributary of the Shashe River

[25] Lobengula was zealous in avoiding confrontation with the Europeans, but when Chief Makombi in the Victoria District refused to pay a traditional tribute, Lobengula was forced to send a punitive force of 2,500 warriors to restore amaNdebele prestige. This force killed around four hundred Mashona, some in front of their white employees to whom they fled for protection. King Lobengula had given stern warning to his fighters when they started the raid. "If you shed one drop of the white man's blood on this raid into Mashonaland, I will have every one of you killed when you return". Significantly no Europeans were killed or injured which points to their discipline. Local residents of Fort Victoria [now Masvingo] complained to the BSA Company administration that they were not being given protection. There were only eighty horse available with only fifty fit for use as cavalry, nevertheless the Company officials, under Dr Jameson demanded that the raiders leave immediately. The Ndebele refused and on 18 July 1893 there was a confused confrontation and when an impi of fifty to eighty amaNdebele did not retire, a patrol under Captain Lendy probably opened fire on them and caused about forty casualties. The amaNdebele returned to Bulawayo with the news that the Europeans had attacked them; Dr Jameson cabled Rhodes with a request to raise a force to confront the amaNdebele.

[26] William Joseph Tainton was in Matabeleland from 1879 when he acted as interpreter to the Missionaries and assisted Lobengula in his dealings with Tati concessionaires. From 1890 he was paid £25 per month for unspecified duties by the British South Africa Company and acted as Colenbrander’s deputy during his absence from Bulawayo in 1891. At the height of the tensions in June – July 1893 he was Lobengula’s secretary and interpreter, but panicked and left Bulawayo hurriedly without the King’s permission.

[27] Johan Colenbrander (1856 – 1918) was trading at Bulawayo at this time accompanied by his wife Mollie. Later played a prominent part in the 1896-7 Umvukela and Chimurenga and the Anglo-Boer War when he raised and commanded a unit called Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts. He played the part of Lord Chelmsford in the film ‘The Symbol of Sacrifice’ and was drowned crossing the Klip River on horseback.

[28] A suburb in north Bulawayo

[29] The telegraph wires were made of copper; a key ingredient in Mashona bangles

[30] From what I can establish they were: the Colenbrander’s, Harry Grant, William Usher, James Fairbairn, James Dawson and Percy Crewe

[31] The Reverend Bowen Rees was a London Missionary Society missionary who with his wife Susannah served at Inyati Mission (now Inyathi) from 1888 to 1918. He was influential in establishing LMS outstations particularly in the Nkayi District at Sivalo, Dakamela, Madliwa, Malinga and Sikhobokhobo to take in the defeated Ndebele people who in 1894 were being evicted from their ancestral lands.

[32] The hammer of a rifle or musket is pulled back and ready to fire when the trigger is pulled

[33] Magwegwe?

[34] Henry James Grant was killed on Altona Farm, Mashonaland in the Charter district about 18 June 1896 and listed in The ’96 Rebellions Reports.

[35] Fengu people, originally closely related to the Zulu who come from the southwest area of the Transkei, in the Eastern Cape of South Africa

[36] John Makunga later accompanied Cecil Rhodes, Hans Sauer, Johan Colenbrander, Vere Stent and John Grootboom into the Matobo Hills as interpreter for the first Umvukela Indaba on Friday, 1st August 1896 with the amaNdebele Indunas.

[37] It began I have the honour to respectively write and state that I am still keeping your advice, laid before me some time ago, that if any trouble happened in my country between me and the white men, I must let you know. I despatched an army for my cattle, stolen by Mashonas. My impi was told to leave their arms behind, coming into the camp, which they did. The white men, after holding a meeting with them, shot my people without cause.

Lobengula went on to summarise his relations with the British South Africa Company, ending the letter: Your Majesty! What I want to know from you is, why do your people kill me?

The letter never reached its London destination. The only mention of it at the time is a passing reference in a Cape Town report to the Foreign Office. The induna Umshete, who was in England, is on his way here…He is the bearer of a letter to the Queen, written…in an illiterate style and containing nothing of importance.

[38] Umshete and Babayane

[39] Fairbairn and Dawson were refused permission to leave Gubulawayo and effectively held as hostages upon Crewe’s return and were in mortal danger as the columns approached, but Lobengula appointed bodyguards for them even as he withdrew from Umvutcha

[40] Colonel Gould Adams with a column of 400 men advanced from the south to very little AmaNdebele opposition and joined Jameson on 15 November 1893 at Bulawayo.

[41] Nguboyenja

[42] Battle of Bembezi which took place on 1 November 1893 when the amaNdebele forces surprised the combined Salisbury and Fort Victoria columns who had halted for lunch. Most of the approximately 10,000 amaNdebele forces were not actively engaged, but those that were suffered heavy casualties from the combined firepower of the five Maxim guns and two seven-pounder guns. See the detailed article in Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[43] Henry Borrow killed with Allan Wilson at the Shangani River on the 3-4 December 1893. See the detailed article on Henry Borrow in Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[44] In his memoirs D.G. Gisborne states that the Battle of Bembezi started about 12:15pm. A few days later on 3 November 1893 he reports that after some skirmishing with amaNdebele forces around Intaba YeZinduna hill James Fairbairn rode into their camp about midday “and reported that the kraal was on fire and that Lobengula had fled northwards.” That same evening “Captain Borrow and twenty men of B Troop had been sent ahead to Bulawayo” so Fairbairn must have returned on his own in the afternoon.

[45] Quoted from O. N. Ransford’s article: “White Man’s Camp” By the morning of 3rd November 1893 Dr Jameson’s column was only a few miles from the royal kraal and acting on the King’s orders the Induna Silvalo blew up the Bulawayo magazine and set fire to the hut city. Through the crackling of burning thatch Usher and Fairbairn could hear the sound of rifle fire coming from the direction of Thabas Induna and they knew that their ordeal was now nearly over. But its last hours might be the most dangerous of all for there were still a number of Matabele hanging about the town and Concession, and the two men decided to spend the night on the roof of Dawson’s store which was the strongest and most fire-proof building in “White Man’s Camp.” They took their rifles and plenty of ammunition up with them, as well as a pack of cards to help pass the time. Although there had been a plot to kill them according to Crewe, they were not molested. Yet is easy for us to appreciate their overwhelming sense of relief when at 8pm Captain Borrow rode into the Concession at the head of a cavalry patrol which had been sent by Major Forbes, the commander of the column, to reconnoitre the royal kraal. “They found them playing poker on the roof” runs a contemporary account of the meeting of the patrol and Fairbairn and Usher. The two men and the soldiers spent the remainder of the night crowded into the store building, and one hopes they celebrated the occasion suitably.

Next day the main column rode into “White Man’s Camp.” Jameson’s force was made up of 652 Europeans and a similar number of African wagon drivers and levies. A company flag was nailed to the top of a prominent tree as the soldiers stood gazing at the kraal burning on the far side of the stream. After forming a strong point, the men then fell out to find bivouacs for themselves. Forbes tells us that “the Matabele had not interfered in any way with the houses belonging to the white men.”

[46] James Fairbairn (1853 – 1894) after losing money on the diamond fields Fairbairn moved Bulawayo as agent and then partner for Cruickshank at Shoshong before becoming James Dawson’s partner between 1881 – 1890. He entertained and helped all the early explorers; Leask, Oates, Phillips and Westbeech and assisted the Jesuits to settle in Bulawayo. Recognised by all throughout Matabeleland he enjoyed the respect and trust of Lobengula.

[47] Bechuanaland Border Police

[48] Fairbairn, Leask, Westbeech and Phillips negotiated an 1884 mining concession with Lobengula for the area between the Gwelo (Gweru) and Hunyani (Manyame) Rivers which was sold to Rhodes in 1889 for £20,000 which was divided between them and Westbeech’s estate.

[49] Rev. John Smith Moffat was assistant Commissioner and Resident Magistrate at Palapye from 1892 - 1895

[50] Robert Moffat, the missionary 1795 - 1883

[51] Loch was well briefed in diplomatic deception. He was asked by Umshete why when Lobengula and Queen Victoria were joined in friendship by treaty was she sending an impi into Matabeleland? Further that that the concession had been obtained by fraud and that no delivery had been taken of the rifles sent by the British South Africa Company. Loch stated the force assembling at Fort Tuli was for their own protection and that the British South Africa Company were coming as friends.

[52] Perhaps another reference to Crewe’s liking for alcohol!

[53] Hwange National Park, P71

[54] Ibid, P72

[55] Hwange National Park, P72

[56] From geni.com and extracted from "Acutts in Africa" by (Aileen) Yvonne Miller nee Gordon-Huntley