Home >

Matabeleland North >

Modern humans originated from Botswana, the ancestral homeland for all anatomically modern humans today, but left due to climate change

Modern humans originated from Botswana, the ancestral homeland for all anatomically modern humans today, but left due to climate change

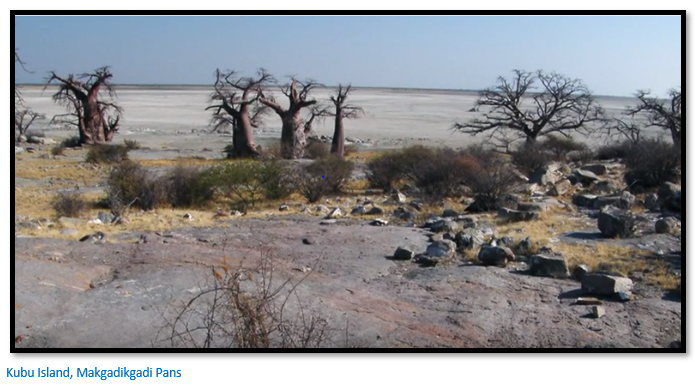

Three hundred kilometres south of Victoria Falls are the Makgadikgadi Pans in Botswana – a seemingly empty and flat landscape that was in earlier Palaeolithic times a gigantic inland super lake of 175,000 square kilometres – about twice the size of Lake Victoria. Over time the climate changed and the waters evaporated leaving many saltpans – including Ntwetwe Pan, Sowa Pan and Nxai Pan that make up the 3,900 square kilometres that comprise Makgadikgadi Pans.

In recent historic times Chapman’s baobab near the present day village of Gweta and named after James Chapman and Thomas Baines who camped under its branches in 1861 guided visitors to the Victoria Falls along the Westbeech road which ran approximately along the present-day Botswana / Zimbabwe border to Pandamatenga.

But in far more ancient times this vast wetland may have been the homeland for anatomically modern man Homo erectus according to a recent study by Professor Vanessa Hayes and her research colleagues.

Even today in the wet summer season as the pans fill with water visitors can see the great migration of large herds of zebra, wildebeest and smaller antelope, such as springbok and gemsbok which move from the Boteti River across to Ntwetwe Pan to graze on the sweet young grass. Hot on their heels come the predators; : the black-maned Kalahari lion as well as leopard, cheetah, wild dog and spotted hyena. Overhead they are accompanied by many species of water birds attracted by the lush vegetation and abundant insects.

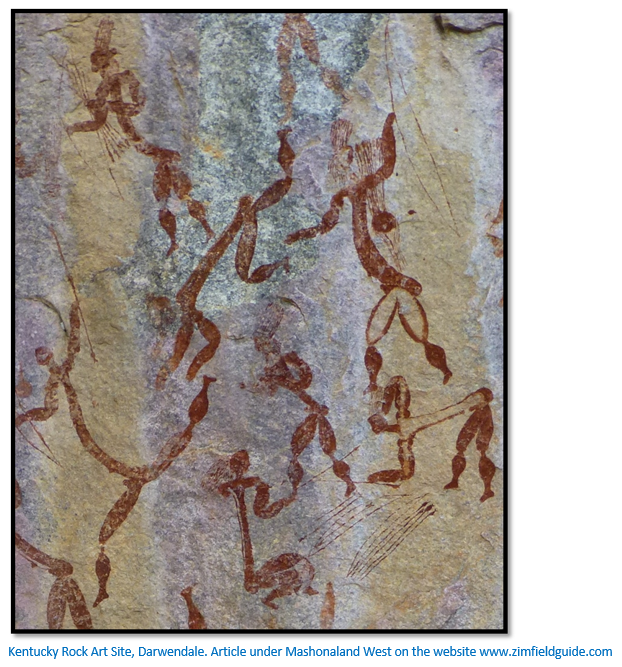

Connection with San rockart in Zimbabwe

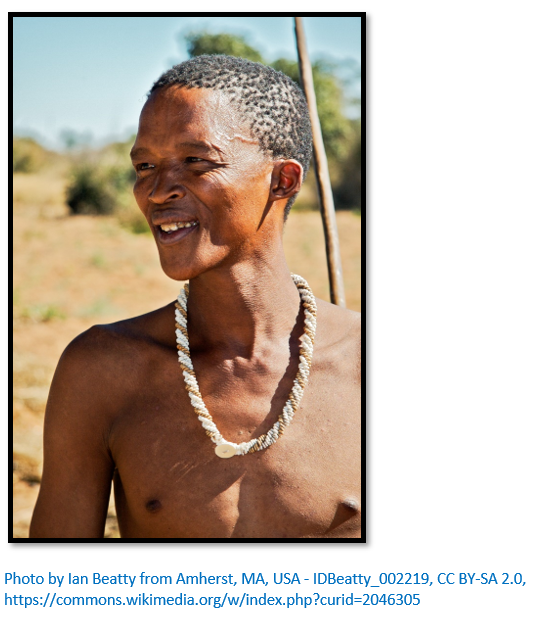

Peter Garlake, the authority on the rock paintings of Zimbabwe suggests they are the least-known artistic treasures of Africa.[i] The rock art is scattered in thousands of granite shelters throughout Mashonaland and Matabeleland and some of the better-known sites are described in articles on this website www.zimfieldguide.com The rock art friezes reflect the beliefs and perceptions of the San people – the same people whose modern DNA formed the basis of the study below - who painted in the late stone age approximately 2,000 years ago and lived through hunting and gathering. Only scattered and fragmented remnants of their society survived into the last century in Zimbabwe, but they were once masters of the entire region.

A new study published in the journal Nature claims that every anatomically modern human (Homo sapiens) on our planet today can be traced back to an ancestral homeland in Botswana.

Study lead Vanessa Hayes, a professor at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Australia wrote in the respected journal Nature “It has been clear for some time that anatomically modern humans appeared in Africa roughly 200,000 years ago.” But this study claims “We all came from the same homeland in southern Africa.”

Botswana’s Makgadikgadi salt pans - once a lakeland refuge

The desiccated landscape of Botswana’s Makgadikgadi pans are the world's second largest salt flats after Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia and Sowa Pan is one of only two places in Africa where soda ash is exploited. During the summer wet season over 350 bird species call the Makgadikgadi home.

But 200,000 years ago the area would have been a flourishing wetland which included the inland delta of the Okavango river and the lush landscape would have been an appealing place for providing abundant food for both wildlife and early anatomically modern humans (Homo erectus who are the direct ancestors of Homo sapiens) in this region – covering parts of Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe. As the climate started changing after 70,000 years, the population of anatomically modern humans began to migrate out of Africa and ultimately, across the world.

Fossil and DNA record

The fossil evidence suggests the first humans, Homo erectus, originated in Eastern Africa or in the northwest in Morocco, but Hayes and her colleagues’ claim to have made a breakthrough, going so far as to even pinpoint the specific region.

Allan Wilson of the University of California, Berkeley developed in the 1980’s what has come to be known as the Mitochondrial Eve hypothesis by looking at a special type of DNA which is passed, unmixed by sexual reproduction, from a mother to her children through the egg cell, its sequence staying the same. But what is true for Eve is also true for Adam as part of the DNA on the y -chromosome is passed unmixed from father to son and can be used to draw up a similar tree that is also rooted in Africa. Where, exactly, y-chromosomal Adam resided has not yet been established.

That early humans lived in northern Botswana has been known for years as many stone tools have been found at the Makgadikgadi pans dating from the Palaeolithic period or Old Stone Age (roughly 2.5 million to 12 thousand years ago) However it is not possible to link particular hominoid species with Palaeolithic tools as they are not species-specific, although it is known they were developed about 1.8m years ago by Homo erectus, an early human that spread over Africa and Asia, but they were also used by erectus’s numerous daughter species, one line of which leads eventually to Homo sapiens.

In recent times the evolutionary birthplace of modern humans was thought to be the East African Great Rift Valley. In very broad terms the evolutionary milestones in human history are:

- The earliest fossil of our genus, Homo, was found in a 2.8 million year old jaw fragment found in East Africa

- 400,000 years ago: Neanderthals - our evolutionary cousins - begin to appear and move across Europe and Asia

- 300,000 to 200,000 years ago: Homo sapiens - modern humans - appear in Africa

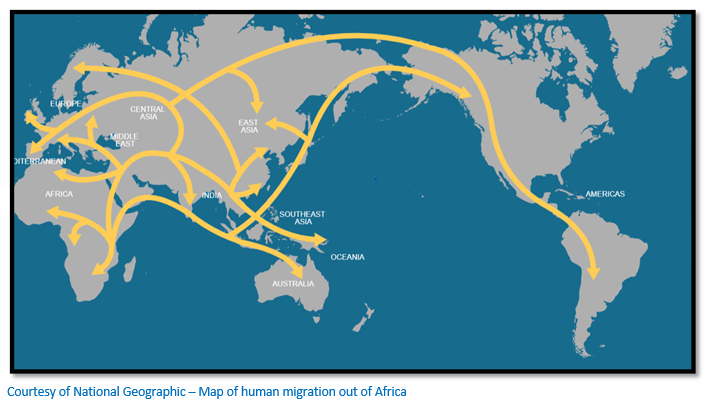

- 50,000 to 40,000 years ago: Modern humans leave Africa and ultimately inhabit every corner of the world.

Fossils carrying a varying mix of features from both modern humans and more ancient hominids seem to be scattered across Africa, from the 260,000 year old Florisbad remains in South Africa and 195,000 year old Omo remains in Ethiopia to the 315.000 year old Jebel Irhoud remains in Morroco although the DNA in each of these finds has become damaged.

This study found that one of the deepest-rooted lines of mitochondrial DNA is commonly found in people living across southern African, and none more so than in the Khoisan people who are a blend of Khoikhoi and San;[ii] two groups who shared similar cultures and languages and whose rockart is found so commonly in the granite regions of Zimbabwe.

Prof. Hayes states: “If we all sit on branches of the human family tree, then Khoisan are the tree’s trunk…By generating mitogenome data for around 200 rare or newly discovered sub-branches of Khoisan lineages, and merging them with all available data, we were able to zoom in on the very base of our evolutionary tree.”[iii]

How the study was done

An international team of researchers took blood samples and sequenced the mitochondrial DNA of 198 individuals in Namibia and Botswana and combined them with previously collected data for a study of the mitochondrial genomes of more than 1,217 people from southern Africa, including Khoisan individuals [called San in my articles on rockart sites in Zimbabwe] who continue to live as hunter-gatherers and herders and foragers in Botswana to trace back the oldest maternal lineage. Combining this data with predictions about the climate and geography in southern Africa around 200,000 years ago, plus studying modern linguistics as well as cultural and geographic distributions of local populations, the authors estimate that the first modern humans lived around Lake Makgadikgadi.

With that information, and data about where the samples were collected, maps of how people who share the same mitochondrial genomes can be constructed. And that is what Dr Hayes and her colleagues did. Follow the branches of the human mitogenomic tree back through time about 200,000 years ago and they converge on northern Botswana[iv] and the Khoisan people who long predate the arrival in the area of both Bantu from farther north in Africa and Europeans from overseas.[v]

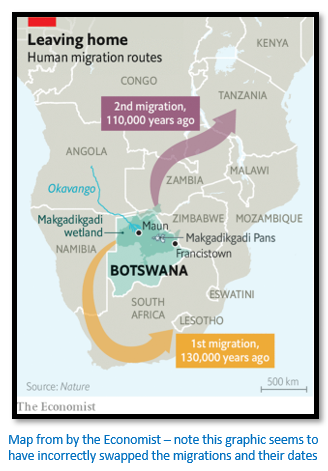

The influence of climate

Co-author Axel Timmermann, the director of the Centre for Climate Physics at Pusan National University in South Korea developed climate computer model simulations that indicated that “the slow wobble of Earth’s axis” brought “periodic shifts in rainfall” across the region. He said: “by comparing the climatic data with timelines of the genetic divergences, we found a striking pattern; more rainfall around 130,000 years ago to the north east of the Makgadikgadi homeland created a green corridor—a vegetated corridor—for migration for the first group to the north east and then around 110,000 years ago to the south west, allowing our earliest ancestors to migrate away from the homeland for the first time.” Prof Hayes added: ”A third population remained in the homeland until today.”[vi]

Analysis revealed that for approximately 70,000 years the early human populations remained steady in isolation, penned into their homeland by desert-like surroundings. but then about 130,000 to 110,000 years ago, something changed: “They go crazy,” says Prof. Hayes. “All these new human lineages just start popping up.”

The scientists concluded that the mitogenomic and climatic data thus seemed to match. The south-western dispersal would have carried the ancestors of modern humans into other parts of southern Africa and would explain the archaeological findings from the Blombos caves on the South Africa coast that have shown this region to be rich in evidence for early humans 100,000 years ago.

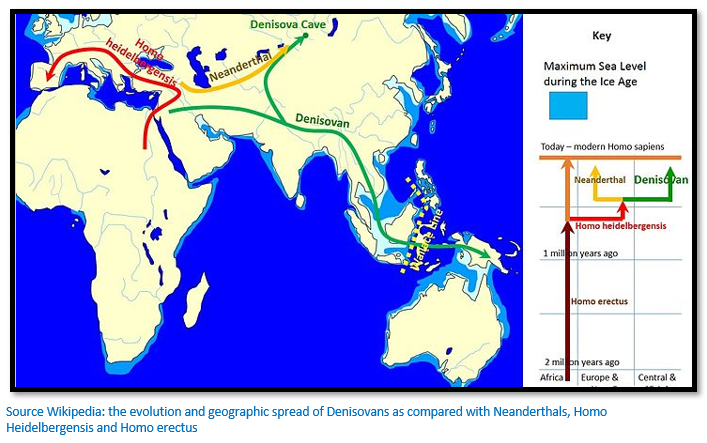

The earlier migration resulted in the earliest anatomically modern humans moving slowly north and then west into Asia and then into Europe, Australia and America and finally interbreeding with the Neanderthals of Europe and Denisovans in Asia.[vii]

Climate caused migration

The researchers think our ancestors settled near Lake Makgadikgadi, Professor Hayes said: "It's an extremely large area, it would have been very wet, it would have been very lush and it would have actually provided a suitable habitat for modern humans and wildlife to have lived."

After staying there for 70,000 years, people began to move on. Shifts in rainfall across the region led to two waves of migration 130,000 and 110,000 years ago, driven by corridors of green fertile land opening up. The first migrants ventured north-east, followed by a second wave of migrants who travelled south-west and a third of the population remained and adapted to the land, forming the population of people living there today.

Prof. Hayes suggests the area of the prehistoric Makgadikgadi lake that had dominated the region may have suffered a huge drought about 130,000 years ago but that humidity increased to the northeast of the homeland, and 110,000 years ago the same happened to the southwest. They speculate that this created passages of lush vegetation for early humans to follow the game animals that were also foraging into new regions.[viii]

The controversy is not yet over

This new study pinpointing Botswana as the region where all modern humans arose has reignited the debate about how and where our species emerged.

Mark Thomas, an evolutionary geneticist at the University College London disagrees with the new study saying: “The inferences from the mitochondrial DNA data are fundamentally flawed.” He points out that although all humans alive today have mitochondrial DNA passed on from a common ancestor—a so-called Mitochondrial Eve—this is just a tiny fraction of our total genetic material.

In an interview with BBC News, Professor Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum said that mitochondrial DNA — the piece of DNA that’s passed down from mother to child — can’t be used to locate a single location for modern human origins. “I think it’s over-reaching, the data, because you’re only looking at one tiny part of the genome so it cannot give you the whole story of our origins,” said Stringer.[ix]

Some researchers do not believe that Homo erectus emerged from a single tree that branched outwards into a global family tree. They suggest our species evolved from different points around Africa that braided together like re-joining streams and lead in an evolutionary process to modern humans.[x]

Others, including Rebecca Cann, a geneticist at the University of Hawaii who was a reviewer of the study and has conducted pioneering work on mitochondrial DNA thought: “this is going to start a lot of conversations, and it’s going to stimulate a lot of new studies. While the study is not perfect, it’s going to get us further down the road.”[xi]

For information on how the Khoisan culture and how their way of life is threatened I would suggest a short article written by Diane Cole based on research by Stephan C. Schuster, Professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, on the npr website.[xii]

Andrew Thompson has also written an informative article in the culture trip called What to Know About the Khoisan, South Africa's First People on how we are probably witnessing the death of the Khoisan culture before our eyes.

[i] P. Garlake. The Hunter’s Vision; the prehistoric art of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Publishing House, Harare, 1995

[ii] https://theculturetrip.com/africa/south-africa/articles/what-to-know-about-the-khoisan-south-africas-first-people/

[iii] Article by Prof V Hayes in https://qz.com/ Scientists now have evidence the evolutionary birthplace of human kind was in northern Botswana dated 31 October 2019

[iv] Article in Science and Technology dated 31 October 2019

[v] Ibid

[vii] www.economist.com/ Where was Eden? Perhaps in a sun-baked salt plain in Botswana

[viii] Article by Prof V Hayes in https://qz.com/ Scientists now have evidence the evolutionary birthplace of human kind was in northern Botswana dated 31 October 2019

[ix] Article by David Lao in Global News dated 30 October 2019

[x] https://www.msn.com/en-in/news/techandscience/controversial-new-study-pinpoints-where-all-modern-humans-arose

[xi] Article by Maya Wei-Haas in National Geographic on 28 October 2019

When to visit:

Closed in the rainy season December to February

Fee:

Entrance and accommodation fees charged

Category:

Province: